Abstract

Background & Objective:

Considering the increasing trends in multi-generational living arrangements, the current study aimed to test the intergenerational transmission of violence hypothesis in three-generational households. We also examined whether and how living in a three-generation household would moderate the negative effect of childhood maltreatment on adults’ abusive and neglectful parenting behaviors.

Method:

We conducted secondary data analysis using data from the Wisconsin Families Study. The study sample included 727 low-income parents of young children, most of whom were African American women with, on average, a high school diploma. We estimated a series of ordinary least squares regression models.

Results:

Our findings indicated that parents who reported a history of childhood abuse, neglect, and witnessing domestic violence showed more frequent use of psychological aggression, physical aggression, and neglectful behavior against their children. Living in a three-generation household played a protective role: The negative effects of a) a history of childhood abuse on the use of neglectful parenting and b) witnessing domestic violence on the use of psychological aggression were reduced for respondents living in a three-generation household (b = −0.11; b = −0.33, ps < .05, respectively).

Conclusion:

The risk of the intergenerational transmission of violence may decrease in three-generation households where parents of young children can meet their needs by sharing family resources or easing the burden of childcare. Further research is needed to identify and specify factors and contexts associated with the beneficial effects of multi-generational living arrangements.

Keywords: childhood maltreatment, maltreating parenting, multi-generational households, social support

The diverse structure of contemporary American families reflects individual choices affected by cultural values and norms, financial constraints, and the occurrence of significant life transitions such as childbearing (Parker, Horowitz, & Rohal, 2015; Lichter, 2019). One of the recent noted trends is an increase in multi-generational living arrangements. In 2016, one-tenth of children in the U.S. were living in three-generation households, which has been doubled compared to approximately two decades ago (Pilkauskas & Cross, 2018). One of the major motivators for this change is to seek social support and meet the needs of family members by sharing family resources (Lichter, 2019). Kin support through coresidence often serves as primary economic and childcare resources for families in need, including families with young children, families in poverty, and single-parent families (Pilkauskas & Cross, 2018; Pilkauskas, 2012).

Although multi-generational living arrangements are linked with poverty and parenthood, little is known about the role of living in a three-generation household in the intergenerational transmission of violence among parents with socioeconomic disadvantages. As discussed earlier, this particular living arrangement can be beneficial in addressing the unmet needs of adult children. Pooling family resources together may reduce economic pressure and parenting demands, and in turn, prevent abusive and neglectful parenting practices. On the other hand, living in a three-generation household may cause significant distress to adult children because of the past, or continuing, relational constraints with their parents that may inflict violence (Kong, 2018a; Kong, Moorman, Martire, & Almeida, 2019).

The current study is purported to address this gap in the literature by drawing data from a sample of low-income parents of young children. Two specific aims were addressed: a) to evaluate the intergenerational transmission of violence hypothesis by examining the association between parents’ childhood family violence experiences and their use of abusive and neglectful parenting practices and b) to examine the moderating effect of living in a three-generation household in the intergenerational transmission of violence.

The Theoretical Framework: The Intergenerational Transmission of Violence

The concept of intergenerational transmission of violence is rooted in several theoretical foundations, including social learning theory (Bandura, 1971, 1978). Social learning theory of aggression posits that children of the parents who prefer aggression to problem-solve tend to exhibit aggressive interpersonal behaviors acquired through observational learning (Bandura, 1978). Their learned violent behaviors are reinforced through family members’ approval and rewards over time, and thus aggressive interpersonal behaviors are used as an acceptable or effective means of conflict resolution (Bandura, 1978; Ehrensaft et al., 2003). In the context of the intergenerational transmission of violence, adults with a history of childhood maltreatment may adopt their learned violent behaviors toward their children when parenting-related issues arise (Fuchs, Mohler, Resch, & Kaess, 2015; Savage, Palmer, & Martin, 2014).

Guided by the intergenerational transmission of violence hypothesis, several studies have examined the long-term effects of childhood maltreatment on later parenting behaviors. Meta-analysis studies have shown that exposure to any childhood abuse and neglect was associated with an increase in harmful and maltreating parenting practices (Madigan et al., 2019; Savage, Tarabulsy, Pearson, Collin-Vezina, & Gagne, 2019). Empirical evidence also suggests that individuals who experienced varying types of childhood abuse and/or neglect were more likely to exhibit negative parenting practices compared to those without such early victimization (Fuchs et al., 2015; Kim, 2009; Lakhdir et al., 2019; Zvara et al., 2015).

Moreover, existing studies suggest the negative impact of low socioeconomic status (SES) on the intergenerational transmission of violence. Zvara and colleagues (2015) revealed that previously maltreated mothers in low-income families with lower educational attainment were more likely to use harsh intrusive parenting than maltreated mothers who were more socioeconomically advantaged. Similarly, mothers who had been maltreated during childhood and also perpetrated violence to their child reported a higher level of sociodemographic risk (i.e., an index compiling low education, single parenthood, receipt of social welfare benefits, young maternal age) and a lack of perceived family support compared to maltreated mothers who did not maltreat their child (St-Laurent, Dubois-Comtois, Milot, & Cantinotti, 2019). These findings suggest that for parents with a history of childhood maltreatment, low SES (e.g., low income, single parenthood) and lack of available resources (e.g., lack of social supports and networks) may increase the risk of continuing the cycle of intergenerational violence with abusive or neglectful parenting practices.

The Moderating Role of Social Support in the Intergenerational Transmission of Violence

Researchers have explored mechanisms of intergenerational transmission of violence, and several studies have well documented the moderating role of social support in mitigating the adverse effects of childhood maltreatment on poor parenting outcomes in adulthood. Belsky’s process model of parenting (1984) offers an important conceptual insight that parenting quality and competence are influenced by the availability of social support, including emotional support and instrumental assistance. Such resources can serve as the key to breaking the cycle of intergenerational transmission of violence: Social support available to parents not only increased positive parent-child interactions through demonstrations of patience, sensitivity, and responsiveness, but also decreased symptoms of parental psychological distress that are known as a prominent risk factor of child abuse and neglect (Belsky, 1984; Feeley, Gottlieb, & Zelkowitz, 2005; Lincoln, Chatters, & Taylor, 2005). Relatedly, mothers’ history of childhood maltreatment was associated with a higher level of depressive symptoms and parenting stress via lower levels of social support (Shenk et al., 2017). Also, Berlin and colleagues (2011) found that mothers’ social isolation mediated the association between mothers’ experiences of childhood physical abuse and their child maltreatment perpetration.

Existing studies indicate that this protective effect of social support can be more pronounced in low-income families. Hashima and Amato (1994) have shown that social support’s protective role against punitive parental behaviors was stronger in low-income families than in higher-income families. Similarly, Kang (2013) investigated low-income mothers with young children and found that high levels of perceived instrumental social support were associated with reduced neglectful parenting via decreased material hardship and increased personal control. Unfortunately, social support for low-SES families tends to be limited. For instance, single mothers with a low level of educational attainment were more likely to show a lower level of informal social support resources compared to mothers with higher educational attainment (Parkes, Sweeting, & Wight, 2015). Informal social support is a significant resource for low-SES families as they often rely on family members, relatives, friends, and neighbors for needs such as childcare, food, housing, or transportation (Henly, Danziger, & Offer, 2005).

Multi-generational Households as a Source of Social Support or Stress

Multigenerational households refer to households in which two or more adult generations co-reside (Ellis & Simmons, 2014; Kreider & Ellis, 2011). There had been a relative lack of studies examining the effect of multigenerational households on intergenerational transmission of violence. Moreover, existing research has yielded mixed findings regarding the role of three-generation households, the most common multigenerational arrangement, in the association between childhood maltreatment and later parenting behaviors.

Some evidence suggests that three-generational arrangements are linked to positive parenting behaviors, such as more structure or rules in their family routines (Pittman & Boswell, 2008). In addition, residing with grandparents can have positive effects on parents’ emotional and mental wellness and help parents have better interactions with their children (Pilkauskas, 2014). The benefits of three-generational arrangements can be particularly relevant to parents in need, such as parents who are single and/or socioeconomically disadvantaged. For example, Pilkauskas (2012) found that single parents were more likely to count on coresidential support as they showed a higher tendency to live with grandparents at the time of birth and early childhood of their children. The author argues that “the needs of the parent generation appeared to be more strongly associated with coresidence than the needs of the grandparent generation” (p. 9).

On the other hand, other evidence supports that coresidence with a grandparent is associated with negative parenting practices among low-income, young, single-mother families (Black & Nitz, 1996; Chase-Lansdale, Brooks-Gunn, & Zamsky, 1994). Grandparents’ presence in the family may be regarded as another source of stress, such as caregiving obligations for older parents or mother-grandmother conflict (Barnett et al., 2012; Spencer, Kalil, Larson, Spieker, & Gilchrist, 2000). This may be particularly the case for adults whose parents were formerly abusive or neglectful if they continue to struggle in the relationships with their parents due to unresolved emotional issues or remaining relational problems (Kong, 2018a).

The Current Study

The review of the theoretical frameworks and previous studies suggests that parents with childhood family violence experiences are at a higher risk of exhibiting poor parenting practices. This risk may be more pronounced among parents with socioeconomic disadvantages, such as low SES or single-parenthood. The primary purpose of the current study is to examine the intergenerational transmission of violence in three-generation households. We aim to extend the existing knowledge base by evaluating the associations between childhood exposure to family violence (i.e., abuse, neglect, and witnessing domestic violence) and the use of abusive and neglectful parenting behaviors, and the moderating effect of living in a three-generational household on the aforementioned associations. The specific hypotheses are as follows:

H1: Childhood exposure to violence is associated with greater abusive and neglectful parenting behaviors.

H2: Living in a three-generation household moderates the effects of childhood exposure to violence on exhibiting abusive and neglectful parenting practices.

Methods

Data Source and Study Sample

The current study utilized data from the Wisconsin Families Study (WiscFams; https://uwsc.wisc.edu/the-wisconsin-families-study-wiscfams/) that surveyed parents living in Milwaukee County in Wisconsin who were at risk for engaging in maltreating behaviors toward their children. WiscFams served as an evaluation of Project GAIN (Getting Access to Income Now), an intervention program designed to enhance parenting and reduce the risk of child maltreatment by assisting families with an array of economic supports who come to the attention of child protective services (CPS). Key features of the GAIN intervention included (1) a comprehensive eligibility assessment for an array of public and private economic supports, and assistance accessing these resources, (2) financial counseling to identify financial goals and steps to achieve them, and improve financial decision-making, and (3) access to one-time emergency cash supplements to alleviate immediate financial stressors. Families were randomly assigned to either a control group or a treatment group; the treatment group families were given the opportunity to participate in the intervention for three – six weeks, and approximately 60% of families ultimately participated in the intervention.

The goal of the WiscFams was to evaluate the effectiveness of the GAIN intervention by conducting in-person interviews with 1,091 parents in the treatment and control group families. A total of 727 parents responded to the baseline survey prior to being randomized into a treatment or control condition, which yielded a response rate of 66.6%. Interviews using a combination of direct interviewer questioning and computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) for sensitive topics lasted about an hour, and survey topics included: parenting, employment, childhood experiences, economic and social support, and service utilization. Data collection of the first wave took place between February 2016 and September 2016.

The analytic sample of this study included 727 respondents who provided usable data in the first wave of the WiscFams. Approximately 60% of respondents reported having the youngest child aged 5 years and younger. A majority of the study sample were women (93.67%), and the average age of respondents was 34 years. Approximately sixty percent of respondents were African American, and another 24% were Non-Hispanic White. On average, respondents obtained a high school diploma or GED certificate (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Sample Characteristics and Frequencies of Key Variables (N = 727)

| Percentage | Mean (SD) | Missingness (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abusive/neglectful parenting behaviors | |||

| Psychological aggression | 1.56 (0.67) | 5 (0.69) | |

| Physical aggression | 1.30 (0.45) | 5 (0.69) | |

| Neglect | 1.42 (0.51) | 10 (1.38) | |

|

| |||

| Childhood exposure to violence | |||

| Childhood abuse | 2.05 (1.16) | 1 (0.28) | |

| Childhood neglect | 2.01 (0.95) | 1 (0.28) | |

| Witnessing domestic violence | 46.77 | 9 (1.93) | |

|

| |||

| Moderator | |||

| Living in a three-generation household | 12.10 | - | |

|

| |||

| Socio-demographic controls | |||

| Female | 93.67 | - | |

| Race | 7 (0.96) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 56.40 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 24.48 | ||

| Hispanic | 13.07 | ||

| Other | 5.09 | ||

| Single parenthood (i.e., currently not living with spouse or partner) | 64.92 | - | |

| Age | 34.00 (9.66) | 2 (0.28) | |

| Educational attainment | 3.43 (1.21) | 3 (0.41) | |

| Total household income | 27230.00 (26435.44) | 27 (3.71) | |

| Treatment group status | 50.76 | - | |

Notes. Weighted descriptive statistics were presented. Percentages are reported for categorical variables, and means are reported for continuous variables with standard deviations reported in parentheses. Educational attainment consists of six categories: 1 = completed elementary school, 2 = some years of high school, 3 = graduated high school/GED, 4 = some years of college, 5 = graduated 2-year community college, 6 = 4-year college degree or more.

Measures

Abusive and Neglectful Parenting Behaviors

The dependent variables in this study were respondents’ abusive and neglectful parenting behaviors, including psychological aggression, physical aggression, and neglect. Psychological aggression was measured by two items (α = 0.60): “In the past 12 months, how often have you (a) sworn at your child/children?; (b) called your child/children stupid, dumb, or other names?” Physical aggression was measured by two items (α = 0.51): “In the past 12 months, how often have you (a) hit your child/children with an object; (b) spanked or slapped your child/children?” Neglect was measured by seven items (α = 0.61) that asked about how often respondents were unable to meet their child/children’s basic needs, such as nutrition, clothing, or health care. Example items included: “In the past 12 months, how often were you unable to take your child/children to a doctor or hospital when they needed it?” Response choices for each item were based on a five-point Likert scale: never (1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), often (4), and very often (5). One notable is that the neglect items may reflect parental behaviors stemming from conditions of poverty but not from willful actions. However they may have arisen, these circumstances place the child at a higher risk of harm. Response choices for each parenting category were averaged to produce a total score with higher scores indicating greater abusive and neglectful behaviors.

Childhood Exposure to Violence

The key independent variables in this study were respondents’ retrospective reports of childhood abuse, neglect, and witnessing domestic violence. Childhood abuse was measured by two items (α = 0.76): “How often did a parent or adult in your home ever (a) call you names, insult you, or put you down?; (b) hit, beat, kick, or physically hurt you in any way (do not include spanking)?” Response choices for each item were based on a five-point Likert scale: never (1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), often (4), and very often (5). A total score was calculated by averaging the two items with higher scores indicating greater exposure to childhood abuse. A history of childhood neglect was measured by four items (α = 0.76): “How often (a) did you feel unloved or unwanted by your parents or primary caregivers; (b) did you remember feeling scared and alone; (c) was there an adult in your household who tried hard to make sure your basic needs (i.e., food, shelter, clothing, and medical care) were met?; (d) was there an adult in your household who made you feel safe and protected?” Response choices for each item were based on a five-point Likert scale: never (1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), often (4), and very often (5). After reverse-coding (c) and (d), a total score was calculated by averaging the four items with higher scores indicating greater exposure to childhood neglect. Witnessing domestic violence was measured by a binary item that asked whether respondents’ parents or adults in your home ever slapped, hit, beat, kicked, or physically hurt each other (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Living in a Three-generation Household

Respondents indicated whether they were living with their parent(s) at the time of data collection (1 = yes, 0 = no). About 12% of respondents were living with their parent(s): 2.0% were living with their fathers; 7.7% with their mothers; 2.3% with both parents.

Control Variables

Based on review of the existing literature, we included respondents’ age, gender (0 = male, 1 = female), race (1 = Black (reference), 2 = Non-Hispanic White, 3 = Hispanic, 4 = Others), educational attainment (1 = completed elementary school, 2 = some years of high school, 3 = graduated high school/GED, 4 = some years of college, 5 = graduated 2-year community college, 6 = 4-year college degree or more), total household income ($, past 12 months), and treatment-control group status (0 = control group; 1 = treatment group). We also included whether they were living with their spouse or partner at the time of data collection (1 = not living with spouse or partner, 0 = living with spouse or partner). About 65% of respondents were not living with a spouse or partner.

Analytic Procedures

Using Stata 15, we estimated ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models predicting abusive and neglectful parenting behaviors. A survey weight was applied to take into account survey non-response and to obtain appropriate standard error estimates for study analyses. Because childhood exposure to violence variables was highly correlated with each other (see Table 2), we ran separate analyses for each independent variable. We first entered the childhood exposure to violence variable, as well as the list of covariates (i.e., main effects models). Next, we included two-way interaction terms between childhood exposure to violence and living in a three-generation household (i.e., two-way interaction models). Complete data were provided by 91.3% of respondents; total household income had the most missing data (n = 27; 3.7% of cases). Because the missingness was not extensive, we used the listwise deletion method but mean-imputed the missing values of the control variables (Kline, 1998).

Table 2.

Correlation Table among Key Variables

| Childhood abuse | Childhood neglect | Witnessing domestic violence | Living in a three-generation household | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood abuse | - | |||

| Childhood neglect | .71* | - | ||

| Witnessing domestic violence | .51* | .47* | - | |

| Living in a three-generation household | −.09* | −.05 | −.11* | - |

Notes. Significance levels are denoted as * p < .05.

Results

Table 1 presents weighted descriptive statistics of sample characteristics and key variables. On average, respondents reported that they rarely used psychological aggression (M = 1.56, SD = 0.67) and never used physical aggression and neglect based on the five-point scale (M = 1.30, SD = 0.45; M = 1.42, SD = 0.51, respectively). Approximately 5% of respondents sometimes or more often used abusive and neglectful parenting behaviors. On average, respondents rarely experienced childhood abuse (M = 2.05, SD = 1.16) and childhood neglect (M = 2.01, SD = 0.95) based on the five-point scale. Approximately 10% of respondents often or very often experienced childhood abuse and neglect. About half of the respondents reported witnessing domestic violence during childhood.

Table 3 summarizes the results of OLS regression models predicting respondents’ negative parenting behaviors (i.e., psychological aggression, physical aggression, neglect) as a function of the independent variables: childhood abuse, childhood neglect, and witnessing domestic violence. Due to high correlations among childhood exposure to violence variables (Table 2), we ran separate analyses for each independent variable. In the main effects models [Table 3 (a)], we found that a parent’s history of childhood abuse was associated with more frequent use of psychological aggression (b = 0.12, p < .001), physical aggression (b = 0.06, p < .001), and neglectful parenting (b = 0.06, p < .001). A parent’s history of childhood neglect was associated with greater psychological aggression (b = 0.13, p < .001), physical aggression (b = 0.07, p < .001), and neglectful parenting (b = 0.09, p < .001). Witnessing domestic violence during childhood was also associated with greater psychological aggression (b = 0.29, p < .001), physical aggression (b = 0.14, p < .001), and neglectful parenting (b = 0.11, p < .01).

Table 3.

Effects of Childhood Exposure to Violence on Exhibiting Abusive and Neglectful Parenting: Moderating Role of Living in a Three-generation Household

| Psychological aggression | Physical aggression | Neglect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (a) | (b) | (a) | (b) | |

|

| ||||||

| b (s.e.) | b (s.e.) | b (s.e.) | ||||

| Childhood abuse | 0.12 (0.02)*** | 0.13 (0.02)*** | 0.06 (0.01)*** | 0.05 (0.02)*** | 0.06 (0.02)*** | 0.07 (0.02)*** |

| Living in a three-generation household | −0.04 (0.07) | 0.17 (0.14) | −0.07 (0.05) | −0.12 (0.10) | −0.03 (0.06) | 0.18 (0.15) |

| Childhood abuse | ||||||

| * Living in a three-generation household | −0.10 (0.06)ǂ | 0.03 (0.05) | −0.11 (0.05)* | |||

|

| ||||||

| Childhood neglect | 0.13 (0.03)*** | 0.14 (0.03)*** | 0.07 (0.02)*** | 0.07 (0.02)*** | 0.09 (0.02)*** | 0.10 (0.02)*** |

| Living in a three-generation household | −0.04 (0.07) | 0.13 (0.16) | −0.06 (0.05) | −0.02 (0.12) | −0.03 (0.06) | 0.20 (0.16) |

| Childhood neglect | ||||||

| * Living in a three-generation household | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.13 (0.06)ǂ | |||

|

| ||||||

| Witnessing domestic violence | 0.29 (0.05)*** | 0.33 (0.05)*** | 0.14 (0.04)*** | 0.16 (0.04)*** | 0.11 (0.04)** | 0.11 (0.04)* |

| Living in a three-generation household | −0.06 (0.07) | 0.07 (0.09) | −0.09 (0.05)ǂ | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.00 (0.08) |

| Witnessing domestic violence | ||||||

| * Living in a three-generation household | −0.33 (0.14)* | −0.20 (0.10)ǂ | −0.04 (0.13) | |||

Notes. Due to high correlations among childhood exposure to violence variables, we ran separate analyses for each independent variable. (a) refers to main effects models and (b) refers to two-way interaction models. Each model included covariates of socio-demographic characteristics (gender, race, age, educational attainment, and total household income), single parenthood, and treatment group status. Unstandardized coefficients are reported with standard errors in parentheses.

Significance levels are denoted as p <.10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

In the two-way interaction models [Table 3 (b)], we found two significant moderating effects of living in a three-generation household on the association between childhood maltreatment and the use of abusive and neglectful parenting behaviors at the significance level of .05. First, the negative effect of a history of childhood abuse on the use of neglectful parenting was reduced for respondents living in a three-generation household (b = −0.11, p < .05). We also found that the negative effect of witnessing domestic violence on the use of psychological aggression was reduced for respondents living in a three-generation household (b = −0.33, p < .05). Although marginally significant (p < .10), living in a three-generation household moderated the associations between a history of childhood abuse and the use of psychological aggression; a history of witnessing domestic violence and the use of physical aggression; and, a history of childhood neglect and the use of neglectful parenting behaviors.

Discussion

This study used data collected from 727 young parents (average age: 34 years) who had been investigated by CPS for child maltreatment but had not received ongoing CPS intervention (“deflected families”). The majority of them were African American women with low family income. Our primary aim was to test the intergenerational transmission of violence hypothesis by examining the association between respondents’ retrospective reports of childhood family violence experiences and their current parenting practices. We also examined whether living in a three-generation household moderated the intergenerational transmission of violence.

Our findings were consistent with the first hypothesis and corroborated prior research in the intergenerational transmission of violence (Madigan et al., 2019; Savage et al., 2019) demonstrating that parents who reported a history of childhood abuse, neglect, and witnessing domestic violence showed more frequent use of psychological aggression, physical aggression, and neglectful behaviors against their children. It was notable that childhood family violence experiences were prevalent among the study sample; for example, 47% of the study sample reported having witnessed domestic violence during childhood. When applying the social learning theory (Bandura, 1978), these parents may have learned violent behaviors from their families of origin and justified their use of abusive/neglectful parenting behaviors (Fuchs et al., 2015; Savage et al., 2014). Given such intergenerational connection, adults with noted disadvantages can benefit from parenting education programs focusing on positive, nurturing parent-child interactions. More importantly, policy interventions are warranted to prevent the replication of abusive and neglectful parenting behaviors across generations.

We also supported our second hypothesis by showing that, despite childhood exposure to violence, living in a three-generation household moderated the effect of childhood maltreatment on later parenting practices. Specifically, parents who had witnessed domestic violence exhibited greater psychological aggression against their child, and this association was weaker among those living in a three-generation household. In the same way, living in a three-generation household significantly moderated the association between parents’ history of childhood abuse and their use of neglectful parenting practices. These findings suggest that three-generation household arrangements may help decrease the use of abusive/neglectful parenting practices among parents of young children with low SES, ultimately promoting positive parent-child interactions and child well-being outcomes. For these adults, three-generational households may serve a means and source of relieving financial demands and allows family resources to be shared that can ultimately reduce the incidence of violence against their children (Pilkauskas & Cross, 2018).

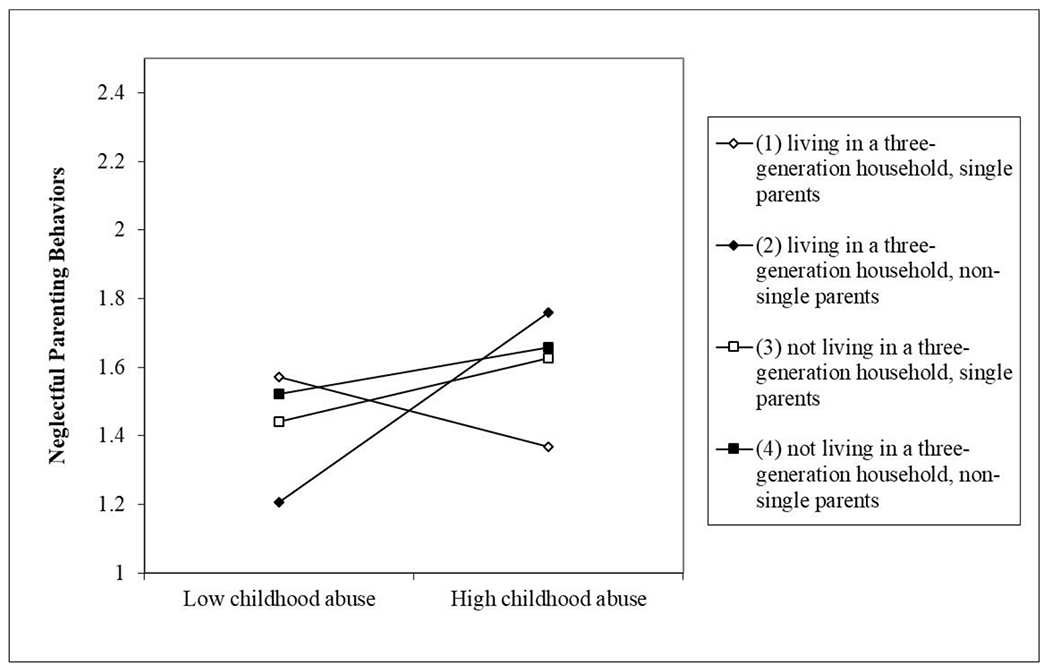

To explore the role of grandparent coresidence as a source of social support, we estimated three-way interaction models and examined whether and how the protective role of living in a three-generation household would differ for single parents (i.e., not living with a spouse or partner) who may have greater needs than those living with a spouse or partner. We found a significant three-way interaction effect of a history of childhood abuse, living in a three-generation household, and single parenthood on neglectful parenting behaviors (Table 4, Figure 1), indicating that the protective effect of living in a three-generation household was more pronounced among single parents. This result may indicate that living in a three-generation household appears to help address parents’ unmet needs such as childcare and thus buffer the negative impact of childhood maltreatment on parenting outcomes. As previous studies suggest, grandparent coresidence appears to offer various social supports in the form of emotional, financial, informational, or instrumental assistance (Dunifon et al., 2014; Mutchler & Baker, 2009; Pittman & Boswell, 2008).

Table 4.

Three-Way Interaction of Childhood Abuse, Living in a Three-generation Household, and Single Parenthood on Predicting Neglectful Parenting Behaviors

| Neglect | ||

|---|---|---|

| b (s.e.) | p value | |

| Childhood abuse | 0.06 (0.03) | .079 |

| Living in a three-generation household | −0.48 (0.23) | .042 |

| Single parenthood | −0.10 (0.10) | .308 |

| Childhood abuse * Living in a three-generation household | 0.18 (0.09) | .059 |

| Childhood abuse * Single parenthood | 0.02 (0.04) | .589 |

| Childhood abuse * Living in a three-generation household* Single parenthood | −0.35 (0.11) | .001 |

| Female | −0.09 (0.09) | .332 |

| Non-Hispanic White | −0.01 (0.05) | .775 |

| Hispanic | −0.08 (0.06) | .179 |

| Other | 0.03 (0.10) | .743 |

| Age | 0.00 (0.00) | .175 |

| Educational attainment | −0.03 (0.02) | .067 |

| Total income | 0.00 (0.00) | .869 |

| Treatment group status | −0.00 (0.04) | .968 |

| Constant | 1.47 (0.16) | <.000 |

Note. Unstandardized coefficients are reported with standard errors in parentheses.

FIGURE 1.

THREE-WAY INTERACTION OF CHILDHOOD ABUSE, LIVING IN A THREE-GENERATION HOUSEHOLD, AND SINGLE PARENTHOOD ON PREDICTING NEGLECFUL PARENTING BEHAVIORS.

To further explore, we conducted other post-hoc analyses to support this speculation. We found that respondents living in a three-generation household tend to use less paid childcare compared to those who were not living with their parents, and this association was stronger for single parents (results available upon request). We also found that for respondents living in a three-generation household, their youngest children were younger than those who were not living with their parents. These results suggest that living in a three-generation household may be most helpful in reducing the occurrence of abusive and neglectful parenting, perhaps through easing the burden of childcare, which warrants further empirical support. Future research should also identify specific aspects of how multi-generational household arrangements are beneficial or stressful to parents and their children.

Our key result concerning the protective role of living in a three-generation household in terms of reducing the use of abusive and neglectful parenting practices shed important insight into adult relationships between grown children with histories of childhood maltreatment and their parents. Our results are somewhat in contrast to those of prior studies that have shown that adult children may continue to be distressed with their previously abusive and neglectful parents, for example, by providing care to them (Kong, 2018b; Kong & Moorman, 2015). Amongst many differences in the current study with Kong’s previous research (i.e., age of respondents and children, relationships with the perpetrating parent), the most notable are the differences in SES status and the roles of adult children and their parents that are tied to a specific phase of life. The impact that childhood family violence has on later family relationships may depend on adult children’s life stages and the concurrent role dynamics between parent-child dyads, which may interact with the needs for social support and resources. Future research should explore the benefits and risks of multi-generational living arrangements based on the past and current relationship quality among co-residing family members.

The current study has limitations. First, the key variables of exposure to childhood violence and current parenting practices were based on self-reported retrospective measures, which may involve recall errors (Macmillion, 2009). Also, childhood abuse measures lacked specific information concerning which parent perpetrated violence against respondents, limiting the assessment of potential stress associated with living in a three-generation household. For example, Kong and Martire (2019) found the negative effect of childhood maltreatment on the relationship with the previously abusive parent, but not with a non-abusive parent. For example, a history of maternal childhood abuse negatively affected adult children’s relationship quality with aging mothers, but not affected their relationship with aging fathers who were previously non-abusive. Relatedly, we cannot rule out an issue of selection bias that adults living in a three-generation household may live with the parent(s) who were less abusive or non-abusive. Second, this study was conducted with a specific high-risk group-families reported to CPS whose cases closed after a CPS investigation. This makes generalizability to other populations somewhat limited, although the nature of the primary research questions renders this population highly relevant. Lastly, the sample size is relatively small. Given the low incidence of some of the phenomena in question, the sample may have lacked statistical power for detecting some hypothesized associations.

Despite the limitations, the current study offers important conceptual contributions. First, the risk of intergenerational transmission of violence may be reduced in three-generation households, which was especially true among single parents. Such parents may relieve their parenting stress by living with their aging parents with whom they can share resources and/or help address child care needs. This overall benefit may exceed potential stress arising from closely interacting with the parents who may have been abusive or neglectful to them as children. Future research is needed to scrutinize and explain factors or contexts that are associated with the benefits of multi-generational living arrangements. Second, our findings emphasize the importance of examining complex family relationships across time and generations. Adults with a history of childhood family violence may have specific concerns and needs in their dyadic relationships with parents and offspring, which may look different in a multi-generational context (Brubaker, 1990). Future research may incorporate the family systems framework (Prest & Protinsky, 2007) to assess better how a history of childhood family violence affects family relationships and dynamics across and among multiple generations.

The lives of individuals are typically embedded in family relationships across the life course (Settersten, 2015), and despite childhood abuse and neglect, living in a three-generation household may help some parents with young children reduce their use of negative parenting practices. When assessing the effects of multi-generational living arrangements, practitioners should consider the specific context of these parent-adult children dyads, including their particular needs, expected familial roles, and SES statuses. Our findings inform practitioners and policymakers that parents with multiple socioeconomic disadvantages may rely heavily on a limited informal social network such as their parents as their major or sole source of social support. Helping the parents diversify and widen their social network and find more sources of support and resources can reduce the concentrated burden and stress in the family, preventing potential conflicts and adequately addressing their specific needs and concerns.

Acknowledgment:

The authors would like to thank the Wisconsin Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention Board for funding to implement Project GAIN.

Contributor Information

Jooyoung Kong, School of Social Work, University of Wisconsin, 1350 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706.

Hana Lee, School of Social Work, University of Wisconsin, 1350 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706.

Kristi S. Slack, School of Social Work, University of Wisconsin, 1350 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706.

Eunji Lee, School of Social Work, University of Wisconsin, 1350 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706.

References

- Bandura A (1971). Social learning theory. New York, NY: General Learning Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1978). Social learning theory of aggression. Journal of Communication, 28, 12–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MA, Mills-Koonce WR, Gustafsson H, Cox M, Vernon-Feagans L, Blair C, …Willoughby M (2012). Mother-Grandmother Conflict, Negative Parenting, and Young Children’s Social Development in Multigenerational Families. Family Relations, 61, 864–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00731.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J (1984). The determinants of parenting: A Process Model. Child Development, 55, 83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, & Dodge KA (2011). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development, 82, 162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, & Nitz K (1996). Grandmother co-residence, parenting, and child development among low income, urban teen mothers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 18, 218–226. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00168-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker TH (1990). Families in later life: A burgeoning research area. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52(4), 959–981. [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Brooks-Gunn J, & Zamsky ES (1994). Young African-American multigenerational families in poverty: Quality of mothering and grandmothering. Child Development, 65, 373–393. doi: 10.2307/1131390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunifon RE, Ziol-Guest KM, & Kopko K (2014). Grandparent coresidence and family well-being: Implications for research and policy. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654, 110–126. 10.1177/0002716214526530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, & Johnson JG (2003). Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: a 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RR, & Simmons T (2014). Coresident grandparents and their grandchildren: 2012. Current Population Reports, P20-576, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Feeley N, Gottlieb L, & Zelkowitz P (2005). Infant, mother, and contextual predictors of mother-very low birth weight infant interaction at 9 months of age. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 26(1), 24–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs A, Mohler E, Resch F, & Kaess M (2015). Impact of a maternal history of childhood abuse on the development of mother-infant interaction during the first year of life. Child Abuse and Neglect, 48, 179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashima PY & Amato PR (1994). Poverty, Social Support, and Parental Behavior. Child Development, 65, 394–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henly JR, Daziger SK, & Offer SA (2005). The contribution of social support to the material well-being of low-income families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 122–140. 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00010.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J (2013). Instrumental social support, material hardship, personal control and neglectful parenting. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 1366–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.05.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J (2009). Type-specific intergenerational transmission of neglectful and physically abusive parenting behaviors among young parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Kong J (2018a). Childhood maltreatment and psychological well-being in later life: The mediating effect of contemporary relationships with the abusive parent. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73, e39–e48. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J (2018b). Effect of caring for an abusive parent on mental health: The mediating role of self-esteem. The Gerontologist, 58, 456–466. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, & Martire LM (2019). Parental childhood maltreatment and the later-life relationship with parents. Psychology and Aging, 34, 900–911. doi: 10.1037/pag0000388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, & Moorman S (2015). Caring for my abuser: Childhood maltreatment and caregiver depression. The Gerontologist, 55, 656–666. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Moorman SM, Martire LM, & Almeida DM (2019). The role of current family relationships in associations between childhood abuse and adult mental health. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74, 858–868. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM, & Ellis R (2011). Living arrangements of children: 2009. Current Population Reports, P70–126, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhdir MPA, Nathwani AA, Ali NA, Farooq S, Azam SI, Khaliq A, & Kadir MM (2019). Intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment: Predictors of child emotional maltreatment among 11 to 17 years old children residing in communities of Karachi, Pakistan. Child Abuse and Neglect, 91, 109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT (2019). Family structure and poverty in the United States. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. doi: 10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosf021.pub2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, & Taylor RJ (2005). Social support, traumatic events, and depressive symptoms among African Americans. Journal of marriage and the family, 67 3, 754–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00167.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan R (2009). The life course consequences of abuse, neglect, and victimization: Challenges for theory, data collection, and methodology. Child Abuse and Neglect, 33, 661–665. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Cyr C, Eirich R, Fearon RMP, Ly A, Rash C, Poole JC, & Alink LRA (2019). Testing the cycle of maltreatment hypothesis: Meta-analytic evidence of the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment. Development and Psychopathology, 31, 23–51. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler JE, & Baker LA (2009). The implications of grandparent coresidence for economic hardship among children in mother-only families. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 1576–1597. 10.1177/0192513X09340527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes A, Sweeting H, & Wight D (2015). Parenting stress and parent support among mothers with high and low education. Journal of Family Psychology, 29, 907–918. doi: 10.1037/fam0000129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker K, Horowitz JM, Rohal M (2015). Parenting in America: Outlook, worries, aspirations are strongly linked to financial situation. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/12/17/parenting-in-america/ [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas N, & Cross C (2018). Beyond the nuclear family: Trends in children living in shared households. Demography, 55, 2283–2297. doi: 10.1007/s13524-018-0719-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas NV (2014). Living with a grandparent and parent in early childhood: Associations with school readiness and differences by demographic characteristics. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2587–2599. doi: 10.1037/a0038179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas N (2012). Three generation family households: Differences by family structure at birth. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 931–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01008.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman LD, & Boswell MK (2008). Low-income multi-generational households. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 851–881. doi: 10.1177/0192513x07312107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prest LA, & Protinsky H (2007). Family systems theory: A unifying framework for codependence. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 21, 352–360. doi: 10.1080/01926189308251005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savage J, Palmer JE, & Martin AB (2014). Intergenerational transmission: Physical abuse and violent vs. nonviolent criminal outcomes. Journal of Family Violence, 29, 739–748. doi: 10.1007/s10896-014-9629-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savage LE, Tarabulsy GM, Pearson J, Collin-Vezina D, & Gagne LM (2019). Maternal history of childhood maltreatment and later parenting behavior: A meta-analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 31, 9–21. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA Jr. (2015). Relationships in time and the life course: The significance of linked lives, research in human development, 12, 217–223, doi: 10.1080/15427609.2015.1071944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shenk CE, Ammerman RT, Teeters AR, Bensman HE, Allen EK, Putnam FW, & Van Ginkel JB (2017). History of maltreatment in childhood and subsequent parenting stress in at-risk, first-time mothers: Identifying points of intervention during home visiting. Prevention Science, 18, 361–370. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0758-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MS, Kalill A, Larson NC, Spieker SJ, & Gilchrist LD (2000). Multigenerational coresidence and childrearing conflict: Links to parenting stress in teenage mothers across the first two years postpartum. Applied Developmental Science, 6, 157–170. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0603_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- St-Laurent D, Dubois-Comtois K, Milot T, & Cantinotti M (2019). Intergenerational continuity/discontinuity of child maltreatment among low-income mother-child dyads: The roles of childhood maltreatment characteristics, maternal psychological functioning, and family ecology. Development and Psychopathology, 31, 189–202. doi: 10.1017/S095457941800161X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvara BJ, Mills-Koonce WR, Appleyard Carmody K, Cox M, & Family Life Project Key, I. (2015). Childhood sexual trauma and subsequent parenting beliefs and behaviors. Child Abuse and Neglect, 44, 87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]