Key Points

Question

Does a multimodal opioid-sparing postoperative pain protocol reduce postoperative opioid consumption compared with standard opioid prescribing after arthroscopic knee or shoulder surgery?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 200 patients, a multimodal opioid-sparing postoperative pain protocol, compared with standard opioid prescribing, significantly reduced postoperative opioid consumption over 6 weeks (median oral morphine equivalent consumption, 0 mg vs 40 mg, respectively).

Meaning

Among patients who underwent arthroscopic knee or shoulder surgery, a multimodal opioid-sparing postoperative pain management protocol significantly reduced postoperative opioid consumption compared with standard opioid prescribing.

Abstract

Importance

In arthroscopic knee and shoulder surgery, there is growing evidence that opioid-sparing protocols may reduce postoperative opioid consumption while adequately addressing patients’ pain. However, there are a lack of prospective, comparative trials evaluating their effectiveness.

Objective

To evaluate the effect of a multimodal, opioid-sparing approach to postoperative pain management compared with the current standard of care in patients undergoing arthroscopic shoulder or knee surgery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial was performed at 3 clinical sites in Ontario, Canada, and enrolled 200 patients from March 2021 to March 2022 with final follow-up completed in April 2022. Adult patients undergoing outpatient arthroscopic shoulder or knee surgery were followed up for 6 weeks postoperatively.

Interventions

The opioid-sparing group (100 participants randomized) received a prescription of naproxen, acetaminophen (paracetamol), and pantoprazole; a limited rescue prescription of hydromorphone; and a patient educational infographic. The control group (100 participants randomized) received the current standard of care determined by the treating surgeon, which consisted of an opioid analgesic.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was postoperative oral morphine equivalent (OME) consumption at 6 weeks after surgery. There were 5 secondary outcomes, including pain, patient satisfaction, opioid refills, quantity of OMEs prescribed at the time of hospital discharge, and adverse events at 6 weeks all reported at 6 weeks after surgery.

Results

Among the 200 patients who were randomized (mean age, 43 years; 73 women [38%]), 193 patients (97%) completed the trial; 98 of whom were randomized to receive standard care and 95 the opioid-sparing protocol. Patients in the opioid-sparing protocol consumed significantly fewer opioids (median, 0 mg; IQR, 0-8.0 mg) than patients in the control group (median, 40.0 mg; IQR, 7.5-105.0; z = −6.55; P < .001). Of the 5 prespecified secondary end points, 4 showed no significant difference. The mean amount of OMEs prescribed was 341.2 mg (95% CI, 310.2-372.2) in the standard care group and 40.4 mg (95% CI, 39.6-41.2) in the opioid-sparing group (mean difference, 300.8 mg; 95% CI, 269.4-332.3; P < .001). There was no significant difference in adverse events at 6 weeks (2 events [2.1%] in the standard care group vs 3 events [3.2%] in the opioid-sparing group), but more patients reported medication-related adverse effects in the standard care group (32% vs 19%, P = .048).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients who underwent arthroscopic knee or shoulder surgery, a multimodal opioid-sparing postoperative pain management protocol, compared with standard opioid prescribing, significantly reduced postoperative opioid consumption over 6 weeks.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04566250

This clinical trial compares the amount of opioids used by patients who underwent arthroscopic knee or shoulder surgery randomized to a pain management protocol involving patient education, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, and acetaminophen or to the current pain management care.

Introduction

Excessive opioid prescribing has been a major contributor to the ongoing opioid epidemic that started in North America and has spread globally.1,2 Due to their potent analgesic effects, opioids have been widely used for postoperative pain control following orthopedic surgery.3 As of 2018, orthopedic surgeons have been identified among the highest prescribers of opioids and routinely prescribe in excess of the recommended guidelines.3,4 Given that a proportion of opioid-naive patients undergoing orthopedic surgery become chronic opioid consumers postoperatively, perioperative prescribing patterns have important long-term implications.5

Shoulder and knee arthroscopy have been among the most commonly performed surgical procedures, with more than 1 million procedures performed yearly in the United States alone based on data from 2006 to 2016.6 Opioids have been the primary analgesic of choice postoperatively among surgeons.7 There remains significant variability in prescribing patterns, with most patients receiving excessive opioids postoperatively.3,7,8,9

The opioid epidemic has prompted a recent emphasis on investigating nonopioid alternatives for pain management among patients undergoing arthroscopic surgery.10 There is evidence that widely available, over-the-counter nonopioid medications can significantly reduce opioid consumption after arthroscopic surgery.11,12 However, the current literature is limited to small sample sizes, narrow patient populations, ineffective strategies, or complex postoperative protocols that include medications with significant adverse effect profiles.13,14,15 Given the common nature of these procedures and evidence of excessive opioid prescribing and utilization, an effective, pragmatic, opioid-sparing postoperative analgesic protocol would be important to develop.

The primary objective of the current randomized clinical trial (RCT) was to compare an opioid-sparing postoperative pain protocol composed primarily of patient education, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and acetaminophen (paracetamol) vs the opioid-based current standard care with respect to postoperative opioid consumption at 6 weeks postoperatively.

Methods

Trial Design

This study was an investigator-initiated, multicenter, parallel, superiority RCT with 1:1 allocation. The rationale, design, and methods have been published previously and the protocol can be found in Supplement 1.16 The Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board approved the trial protocol prior to initiation, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to study inclusion. The trial was prospectively registered on ClinicalTrials.gov before the first participant was recruited and follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines.17 No changes in the study methods were made following trial registration. The statistical analysis plan [SAP] is available in Supplement 2.

Participants

From March 2021 to March 2022, eligible patients were recruited from 3 academic clinical sites in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Eligible patients included those aged 18 years or older who were scheduled for elective arthroscopic knee or shoulder surgery. The complete list of included procedures can be found in eTable 1 in Supplement 3. The operations were performed by a group of 8 arthroscopic surgeons, and surgical decision-making and procedures were at the discretion of the treating surgeons. In keeping with a pragmatic design, the decision to use regional and/or general anesthetic was made at the discretion of the treating anesthesiologist and surgeon. Exclusion criteria consisted of the following: (1) chronic opioid use preoperatively; (2) surgery related to a workers’ compensation claim; (3) operative time was more than 3 hours; (4) procedure required overnight admission in hospital; and/or (5) contraindication or allergy to NSAIDs, acetaminophen, morphine, or hydromorphone.

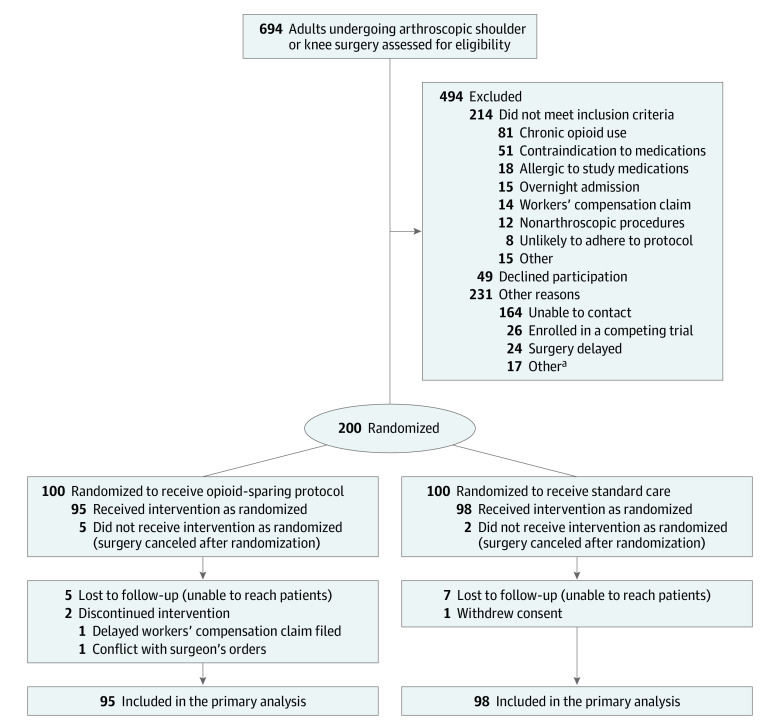

Randomization

Eligible patients were randomized immediately prior to surgery using a centralized computer randomization system (REDCap Cloud) allowing for automated, internet-based randomization to allocate patients to the control or intervention group in a 1:1 fashion. By using a centralized and automated randomization system, sequence generation was ensured to be random and allocation was concealed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Recruitment, Randomization, and Patient Flow in the NO PAin Trial.

aNo further details were recorded.

Interventions

In the intervention group, patients received a standardized protocol that was developed based on the current literature and in consultation with surgeons, anesthesiologists, perioperative nurses, and pharmacists with expertise in perioperative care11,18: (1) 500 mg of naproxen taken orally twice a day as-needed (60, 500-mg tablets) and 40 mg of pantoprazole taken orally daily while consuming naproxen; (2) 1000 mg of acetaminophen taken orally every 6 hours as needed (100, 500-mg tablets); (3) opioid rescue prescription consisting of 1 mg of hydromorphone taken orally every 4 hours as needed (10, 1-mg tablets). Patients were instructed to take the opioid only when the nonopioid protocol was unable to provide adequate pain relief; and (4) patient educational infographic: provided information on both pharmacological and nonpharmacological pain management strategies as well as information regarding the risks of opioid misuse (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3).

Patients in the intervention group were prescribed all medications on an as-needed basis based on pain levels but were encouraged to use both naproxen and acetaminophen even when experiencing mild pain in the first week following surgery. After consultation with a perioperative pharmacist as well as a review of the existing literature, 500 mg of naproxen taken twice a day was chosen to provide optimal analgesia in the postoperative setting.19

The standard care group received a postoperative opioid prescription that aligned with the treating surgeon’s current prescribing habits. To mitigate the risk of bias, each surgeon provided a description of their current prescribing habits for each of the included procedures prior to beginning patient enrollment in the study. These prescriptions were kept consistent throughout the duration of the study. The standard care prescription varied by surgeon and procedure and included oxycodone, codeine, or hydromorphone; ranged from 20 to 80 tablets; and was prescribed to be taken on an as-needed basis. Patients in the standard care group did not receive standardized counseling about the use of NSAIDs or acetaminophen for minor or moderate postoperative pain, and these medications were not routinely prescribed postoperatively for this group. Patients were allowed to use these over-the-counter medications at their own discretion.

All patients received a standardized perioperative pain management protocol, which included: (1) 1000 mg of acetaminophen taken orally every 6 hours as needed, (2) 1 dose of 15 to 30 mg of intravenous (IV) ketorolac, (3) 4 to 8 mg of oral or IV ondansetron every 8 hours as needed for nausea or vomiting, (4) 25 to 50 mg of oral or IV dimenhydrinate every 6 hours as needed for nausea or vomiting, (5) an extra-articular injection of 10 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine into the soft tissues surrounding the portal sites, (6) 10 mg of oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release tablet taken orally one time during recovery or 5 mg of oxycodone regular release, and (7) 1 mg of hydromorphone taken orally every 4 hours as needed (or morphine or oxycodone if intolerant or allergic). Patients who underwent a regional anesthetic block did not receive a local anesthetic injection intraoperatively. This perioperative protocol was the standardized institutional protocol for patients undergoing arthroscopic surgery.

After randomization, a member of the research team placed the appropriate postoperative prescription in each patient’s chart for the surgeon to review and sign prior to patient discharge. All patients in either group were instructed to contact the trial methods center if a prescription refill was required or if they were experiencing adverse effects or pain that was uncontrolled by their current pain prescription. For urgent issues, the orthopedic team on call at each hospital was available.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was total outpatient opioid consumption, at 6 weeks postoperatively. Opioid consumption was recorded by a patient-reported medication diary. Opioid quantities were converted to oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) to allow for data pooling and analysis (eTable 2 in Supplement 3).20

Secondary outcomes of interest included (1) patient-reported pain, defined using a 100-point visual analog scale (VAS; range, 0-100, with 0, no pain; 100, worst pain possible),21 at 6 weeks; (2) number of OMEs prescribed at discharge; (3) patient-reported satisfaction with pain control using a modified, 4-point (always, usually, sometimes, never) question from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems22 questionnaire at 6 weeks; (4) opioid refill requests completed from hospital discharge to 6 weeks; and (5) adverse events up to 6 weeks after surgery. The minimally clinically important difference for the VAS score was set at 10 based on a recent prospective study evaluating postoperative, outpatient pain scores.23 No changes in trial outcomes were made after the trial had commenced.

Other prespecified outcomes included patient-reported pain at 2 weeks postoperatively and patient-reported medication adverse events. Patient-reported medication adverse effects were recorded in the daily medication diary collected for 14 days after surgery.

Adverse events were adjudicated by an independent, blinded adjudication committee composed of 3 orthopedic surgeons. Study participants were followed up at 2 and 6 weeks postoperatively for all primary and secondary outcomes. Patient follow-up occurred in the orthopedic clinic or by phone depending on patient availability.

Blinding

Given that a patient educational infographic was provided to patients in the intervention group, blinding of patients was not possible. The treating surgeons were also not blinded to treatment groups because they were the prescribing physicians for the postoperative analgesics. Both outcome assessors and data analysts were blinded to patient treatment groups. All data analysis was completed using blinded data prior to unblinding of treatment groups.

Sample Size

The justification for the trial sample size has been previously published.16 Briefly, based on the published literature, it was hypothesized that the intervention group would have a relative reduction in postoperative OME consumption of 33%. This was based on the prescribed OMEs and on previously published practice patterns and SDs for OMEs consumed by patients after undergoing arthroscopic surgery. It was predicted that the intervention group would consume on average 20 OMEs and the standard care group would consume 30 OMEs (SAP in Supplement 2).7,24 Assuming an α of .05 and a β of 80%, the required sample size was 68 patients per group. To conservatively account for a 30% loss to follow-up and any crossovers, the sample size was increased to 200 patients in total.25

Statistical Methods

Patients who were randomized but had their surgeries cancelled were not included in the analysis. All patients who underwent surgery were analyzed according to their randomization group and were included in the final analyses. The baseline characteristics were presented descriptively with means and SDs for continuous variables, and count and percentage for categorical variables; 95% CIs were used when presenting pooled, imputed data.

A full SAP was completed and reviewed by a statistician prior to data analysis (Supplement 2). The pertinent details of this SAP16were also published previously in the study protocol and can be found in Supplement 1. The data were assessed for normality, and if this assumption was met, a t test was to be used; if data were not normal despite log transformation, a Mann-Whitney U test was to be used. Thus, based on this approach specified in the SAP, the primary outcome was analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U Test. A t test was used for normally distributed, continuous, secondary outcomes. For categorical secondary outcomes, a χ2 test was performed. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. Missing data were handled using multiple imputation, with the use of complete case analysis and 10 iterations. Mean differences (MDs) are reported with 95% CIs, and medians are reported with IQRs where appropriate. For categorical data, odds ratios (ORs) are presented with 95% CIs. All analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, version 26).

Three a priori subgroup analyses evaluating sex (men vs women), joint (knee vs shoulder), and anesthetic strategy (regional block vs no regional block) were performed using a Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test with fixed effects.

Post Hoc Analyses

A sensitivity analysis was performed comparing complete cases vs multiple imputation results for the primary outcome. Sensitivity analyses were also performed to assess the effect of study site or surgical procedure (using the 5 most common surgical procedures) on the primary outcome. Study site and surgical procedure were added as random effects to respective mixed-effect models. Postoperative pain and opioid consumption were analyzed descriptively and comparatively between groups for days 0 to 3 postoperatively, using the same analysis plan used to analyze opioid consumption and pain levels for the primary and secondary outcome analysis. Patient satisfaction was analyzed using the full scale (1-4, without collapsing into a dichotomous variable).

All statistical analyses were performed as 2-sided tests with a significance threshold of P < .05.

Results

Participant Flow and Recruitment

A total of 694 patients were screened for eligibility, and 200 patients were randomized, with 100 patients assigned to each group (Figure 1). Seven patients (2 patients from the control group, 5 patients from the intervention group) had their procedures cancelled after randomization for various reasons unrelated to the trial itself and, thus, were excluded from further analysis. For the primary outcome, the follow-up rate was 95.3% (184 of 193) at 2 weeks and 92.2% (178 of 193) at 6 weeks. Recruitment began in March 2021, and final follow-up was completed in April 2022.

Baseline Data

The overall mean age of enrolled patients was 43.0 (SD, 15.3) years. The majority of patients were men (62.2%; 120 of 193), with similar proportions of men and women in both groups. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 29.2 (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). Most patients were involved in moderate to vigorous physical activity prior to their injury (75.1%; 145 of 193) and employed at the time of recruitment (71.5%; 138 of 193; Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristics | No. (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Opioid-sparing protocol (n = 95) | Standard care (n = 98) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 42.3 (15.2) | 43.0 (15.3) |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 62 (65.3) | 58 (59.2) |

| Women | 33 (34.7) | 40 (40.8) |

| BMI | ||

| Mean (SD) | 29.1 (6.3) | 29.3 (6.8) |

| Underweight <18.5 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Normal weight 18.5 to <25 | 27 (28.4) | 28 (28.6) |

| Overweight 25 to <30 | 32 (33.7) | 32 (32.7) |

| Obese 30 to <40 | 31 (32.6) | 35 (35.7) |

| Morbidly obese ≥40 | 4 (4.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| Use of tobacco products | ||

| None | 78 (82.1) | 82 (83.7) |

| Current smoker | 13 (13.7) | 8 (8.2) |

| Previous smoker | 4 (4.2) | 8 (8.2) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| None | 33 (34.7) | 35 (35.7) |

| Yes, <5 drinks/wk | 43 (45.3) | 35 (35.7) |

| Yes, ≥5 drinks/wk | 19 (20.0) | 28 (28.6) |

| Sport activity level prior to injury | ||

| None | 7 (7.4) | 6 (6.1) |

| Light | 17 (17.9) | 18 (18.4) |

| Moderate | 30 (31.6) | 44 (44.9) |

| Vigorous | 41 (43.2) | 30 (30.6) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Back pain | 16 (16.8) | 11 (11.2) |

| Asthma | 6 (6.3) | 10 (10.2) |

| Depression | 3 (3.2) | 12 (12.2) |

| Diabetes | 3 (3.2) | 4 (4.1) |

| Osteoporosis | 2 (2.1) | 3 (3.1) |

| Anxiety | 0 | 2 (2.0) |

| Hypertension | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 0 | 2 (2.0) |

| Ulcers | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) |

| Othera | 7 (7.4) | 5 (5.1) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 66 (69.5) | 72 (73.5) |

| Retired | 12 (12.6) | 11 (11.2) |

| Student | 9 (9.5) | 11 (11.2) |

| Not employed, other | 8 (8.4) | 4 (4.1) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

One patient (1.0%) each in one treatment group: Lyme disease, multiple sclerosis, neck pain, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea. The following comorbidities were reported by 1 patient (1.1%) each in the other treatment group: anemia, cancer, B12 deficiency, fibroids, irritable bowel syndrome, hypoglycemia, and Parkinson disease.

Surgical Details

Most patients underwent knee surgery (73.1%; 141 of 193), with similar proportions between groups. Of the knee surgeries, 93 (48.2%) were meniscectomy, the most commonly performed procedure, and 25 (13.0%) were biceps tenotomy or tenodesis in the shoulder. One hundred eighty-four patients (95.3%) had a general anesthetic, and 35 (18.1%) also had a regional block. Mean operative time was 48.6 (SD, 32.0) minutes and was similar between the 2 groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Surgical Details.

| Variable | No. (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Opioid-sparing protocol (n = 95) | Standard care (n = 98) | |

| Operative joint | ||

| Knee | 72 (75.8) | 69 (70.4) |

| Shoulder | 23 (24.2) | 29 (29.6) |

| Side | ||

| Left | 54 (56.8) | 62 (63.3) |

| Knee procedures performed | ||

| Meniscectomy | 46 (48.4) | 47 (48.0) |

| Irrigation and/or debridement | 29 (30.5) | 33 (33.7) |

| Chondroplasty | 22 (23.2) | 29 (29.6) |

| Diagnostic arthroscopy | 24 (25.3) | 20 (20.4) |

| ACL reconstruction (± LET) | 15 (15.8) | 15 (15.3) |

| Loose body removal | 10 (10.5) | 8 (8.2) |

| Meniscal repair | 4 (4.2) | 11 (11.2) |

| MPFL reconstruction (not including TTO) | 3 (3.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| Microfracture | 4 (4.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| Synovectomy | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.1) |

| Fixation of osteochondral lesion | 2 (2.1) | 0 |

| Shoulder procedures performed | ||

| Biceps tenotomy or tenodesis | 14.7 (7.3) | 11 (11.2) |

| Rotator cuff repair | 9 (9.5) | 15 (15.3) |

| Diagnostic arthroscopy | 10 (10.5) | 12 (12.2) |

| Capsular release | 8 (8.4) | 8 (8.2) |

| Subacromial decompression | 5 (5.3) | 10 (10.2) |

| Shoulder stabilization | 6 (6.3) | 8 (8.2) |

| Irrigation and/or debridement | 6 (6.3) | 6 (6.1) |

| SLAP repair | 3 (3.2) | 6 (6.1) |

| Synovectomy | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) |

| Loose body removal | 0 | 1 (1.0) |

| Anesthetic strategy, No./total (%) | ||

| General | 90 (94.7) | 94 (95.9) |

| Spinal | 3 (3.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| Not recorded | 2 (2.1%) | 3 (3.1%) |

| Supplemental regional block | ||

| Yes | 17 (17.9) | 18 (18.4) |

| Operative time, median (IQR), min | 39.0 (22.0-70.0) | 42.5 (21.8-68.3) |

Abbreviations: ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; LET, lateral extra-articular tenodesis; MPFL, medial patellofemoral ligament; SLAP, superior labrum anterior to posterior; TTO, tibial tubercle osteotomy.

Primary Outcome

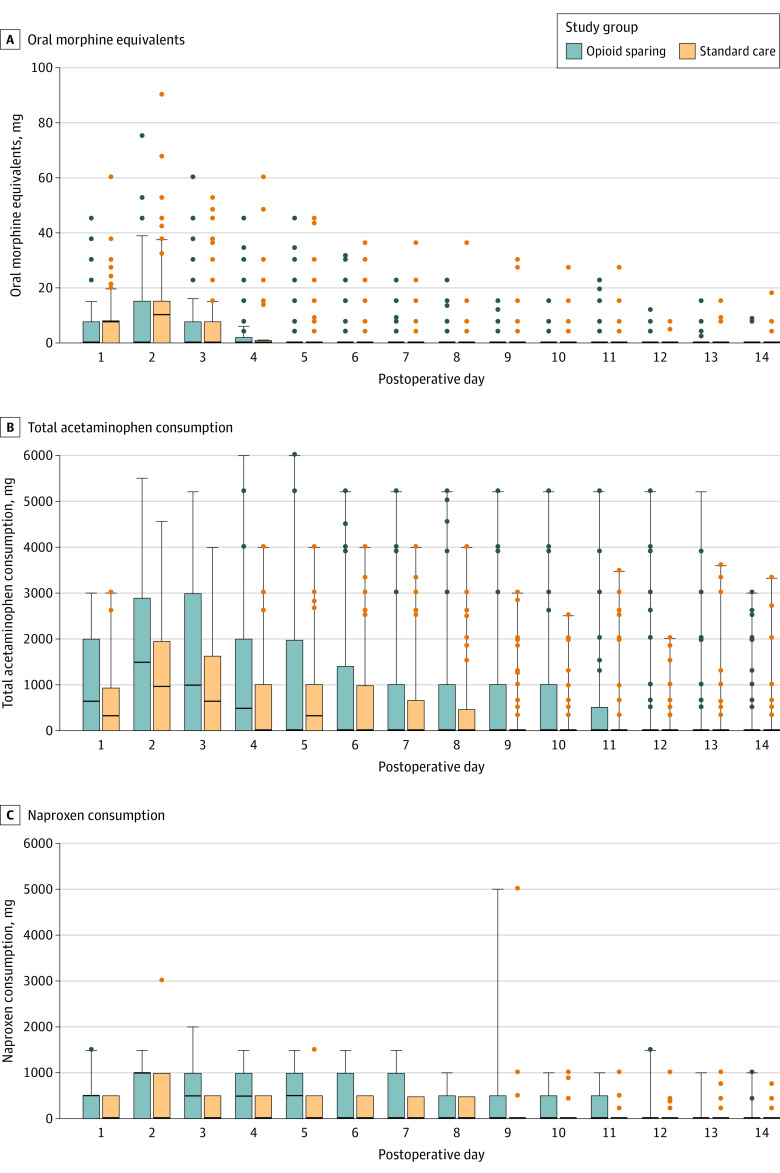

The mean amount of OMEs consumed at 6 weeks after surgery in the standard care group was 72.6 mg, compared to 8.4 mg in the opioid-sparing group (MD, 64.2 mg; 95% CI, 44.4-84.0; P < .001). The distribution of OMEs consumed was not normal, and this remained the case after log transformation. Thus according to the prespecified SAP, a Mann-Whitney U test was performed. For the primary analysis of the primary outcome, patients in the opioid-sparing protocol consumed significantly fewer opioids (median, 0 mg; IQR, 0-8.0) than patients in the control group (median, 40.0 mg; IQR, 7.5-105.0; z = −6.55; P < .001). eFigure 2 in Supplement 3 demonstrates a histogram of total opioid consumption in each group. Figure 2 demonstrates daily medication use in each group for the first 14 days after surgery.

Figure 2. Pain Medication Consumption Over First 14 Days After Surgery.

Whiskers indicate quartile 3 plus 1.5 times the IQR; bars, IQR (quartile 1 to quartile 3); the dots, outlying values; black lines, medians. The sample sizes for all data points are 95 for the opioid-sparing group and 98 for standard care group.

Secondary Outcomes

At 6 weeks, patients in the standard care group reported a mean pain score of 14.8 (95% CI, 11.3-18.3) compared with 12.2 (95% CI, 8.3-16.1) in the opioid-sparing group (MD, 2.6; 95% CI, −2.7 to 7.9, P = .76). Differences in pain scores did not exceed the prespecified minimally clinically important difference of 10 points. eFigure 3 in Supplement 3 demonstrates mean daily VAS scores in each group over the first 14 days.

Significantly fewer OMEs were prescribed at discharge in the opioid-sparing group (mean, 40.4 mg; 95% CI, 39.6-41.2) compared with the standard care group (mean, 341.2 mg; 95% CI, 310.2-372.2), with an MD of 300.8 mg (95% CI, 269.4-332.3; P < .001).

Most patients were satisfied with their pain control at 6 weeks in the standard care group (80.6%) and the opioid-sparing group (83.2%), with no significant difference between the 2 groups with an OR for unsatisfied patients in the standard care group of 1.22 (95% CI, 0.5-3.1; P = .90).

Eight patients in the trial requested additional opioids after discharge: 6 patients (6.2%) in the standard care group and 22 patients (2.1%) in the opioid-sparing group, with no significant difference between the 2 groups with an OR for refill request in standard care group of 3.07 (95% CI, 0.6-15.6; P = .16; Table 3).

Table 3. Study Outcomes by Treatment Group.

| Opioid-sparing protocol (n = 95) | Standard care (n = 98) | Difference (95% CI) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference | ||||

| Total OMEs consumed, mg | ||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 8.4 (5.3-11.5) | 72.6 (53.2 to 92.0) | MD, 64.2 (44.4 to 84.0) | <.001b |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0-8.0) | 40.0 (7.5 to 105.0) | ||

| VAS score, mean (95% CI)c | ||||

| 2 wk | 15.4 (11.3-19.5) | 17.8 (13.9 to 21.7) | MD, 2.7 (−3.0 to 8.4) | .42d |

| 6 wk | 12.2 (8.3-16.1) | 14.8 (11.3 to 18.3) | MD, 2.6 (−2.7 to 7.9) | .76 |

| OMEs prescribed at discharge, mg | ||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 40.4 (39.6-41.2) | 341.2 (310.2 to 372.2) | MD, 300.8 (269.4 to 332.3) | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 40 (40-40) | 300 (300 to 450) | ||

| Patient-reported satisfaction at 6 wk, No. (%) | OR, 1.2 (0.5 to 3.1) | .90 | ||

| Satisfied (always, usually) | 79 (83.2) | 79 (80.6) | ||

| Unsatisfied (sometimes, never) | 9 (9.5) | 11 (11.2) | ||

| Opioid refill requests completed, No. (%) | 2 (2.1) | 6 (6.2) | OR, 3.07 (0.6 to 15.6) | .16 |

| Any adverse events, No. (%) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (2.1) | OR, 0.65 (0.1 to 4.0) | .63 |

Abbreviations: MD, mean difference; OR, odds ratio; OMEs; oral morphine equivalents; VAS, visual analog scale.

The t test was used for comparing means of continuous variables; Mann-Whitney U test, for medians of continuous variables; and the Pearson χ2test, for categorical variables.

Mann-Whitney U, z = −6.55.

Patients were instructed to draw a line on VAS scale (range, 0-100; 0, no pain; 100, the worst pain possible) to indicate their pain level.

t Test, t = .911.

Five adverse events occurred in the trial during the 6-week follow-up period, with 2 events (2.1%) in the standard care group and 3 (3.2%) in the opioid-sparing group. One serious adverse event occurred (deep vein thrombosis) in the intervention group, and only 1 adverse event (uncontrolled postoperative pain in the standard care group) was determined by the adjudication committee to be directly related to the surgery (not the trial interventions). In the opioid-sparing group, 1 patient experienced calf swelling and another patient, postoperative Baker cyst. One patient in the standard care group reported shoulder adhesive capsulitis.

Additional Prespecified Outcomes

At 2 weeks, patients in the standard care group had a mean VAS pain score of 17.8 (95% CI, 13.9-21.7) and patients in the opioid-sparing group, 15.4 (95% CI, 11.3-19.5) for an MD of 2.7 (95% CI, −3.0 to 8.4; P = .42).

Forty-nine patients (31 [ 31.6%] in the standard care group and 18 [18.9%] in the opioid-sparing group) reported a total of 53 possible medication-related adverse effects in the 2-week medication diary (Table 4). The standard care group had a significantly higher rate of medication adverse effects than did the opioid-sparing group (OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.02-3.86; P = .048). The most commonly reported adverse effects in the standard care group were drowsiness (20.4%), gastrointestinal upset (17.3%), and dizziness (6.1%), whereas patients in the opioid-sparing group reported gastrointestinal upset (12.6%), drowsiness (7.4%), and dizziness (2.1%).

Table 4. Patient-Reported Medication Adverse Effects.

| Patient-reported adverse outcome | No. (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Opioid-sparing protocol (n = 95) | Standard care (n =98) | |

| ≥1 Reported adverse effects | 18 (18.9) | 31 (31.6) |

| Gastrointestinal upset | 12 (12.6) | 17 (17.3) |

| Drowsiness | 7 (7.4) | 20 (20.4) |

| Dizziness | 2 (2.1) | 6 (6.1) |

| Constipation | 2 (2.1) | 5 (5.1) |

| Pruritus | 0 | 3 (3.1) |

| Headaches | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.0) |

Ancillary Analyses

The prespecified subgroup analyses were performed as planned. None of the subgroups (sex, joint, or use of regional block) demonstrated a significant subgroup effect (eFigure 4 in Supplement 3). A sensitivity analysis using the original data set with missing data vs the data set with imputed data did not produce any difference in significant results compared with the primary analysis.

Post Hoc Analyses

There was no significant interaction effect of site or surgical procedure on the primary outcome based on inclusion of these variables as a random effect to a mixed-effects modeling (eFigure 4 in Supplement 3). There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in terms of mean VAS pain score for postoperative days 0 to 3 (mean, 47.5 for standard care group vs 42.2 for intervention group; P = .34). Total opioid consumption for postoperative days 0 to 3 was significantly higher in the standard care group than in the intervention group (mean, 44.3 vs 8.9 OMEs; median, 30 vs 0 OMEs consumed; z = −5.7; P < .001). Patient satisfaction was not significantly different between the 2 groups when the scale was analyzed as a 4-point scale (eTables 3 and 4 in Supplement 3).

Discussion

In this pragmatic RCT evaluating patients undergoing outpatient shoulder or knee arthroscopy, an opioid-sparing postoperative pain management protocol significantly reduced postoperative opioid consumption compared with a standard opioid prescription in the 6 weeks following surgery. Significantly fewer opioids were prescribed in the opioid-sparing group. Significantly fewer patients reported medication-related adverse effects in the opioid-sparing group. No significant differences in patient-reported pain, opioid refills, or patient-reported satisfaction scores between groups at 6 weeks were found. Adverse events were generally transient, not serious, and similar between groups.

Multimodal analgesic protocols for postoperative pain control have demonstrated efficacy across several surgical domains.26 The underlying premise is that concurrent administration of multiple analgesics results in an additive effect and has the potential to reduce opioid consumption while maximizing pain control. NSAIDS are potent analgesics that form a cornerstone of multimodal analgesic protocols.26 Although NSAIDs carry risks, they were well tolerated in the current study and may be considered a first-line analgesic for patients without contraindications.26,27,28 Similarly, acetaminophen represents an effective nonopioid analgesic that has an additive effect when used in conjunction with NSAIDs.29 The use of a primarily nonopioid multimodal analgesic protocol in the current study reduced total opioid consumption and patient-reported adverse effects from medication.

Given the recognized harms of opioids, there has been substantial interest in the development and utilization of opioid-sparing protocols for postoperative pain management among patients undergoing orthopedic surgery. Different opioid-sparing postoperative protocols have been investigated, with varying levels of efficacy.15,18 Moutzouros et al13,18 have evaluated the efficacy of a nonopioid analgesic protocol in several patient populations undergoing arthroscopic surgery and demonstrated that it provided similar pain control to a standard opioid prescription. However, the inclusion of prescription medications including benzodiazepines and gabapentin may limit the applicability and widespread use of such protocols.13,18,26,30 The current study used widely available, well-tolerated, over-the-counter medications as the basis of the multimodal analgesic protocol.

A limited opioid prescription was provided to all patients in the intervention group as a rescue analgesia. Reducing the total amount of opioids prescribed in the postoperative setting has several important implications. First, there is evidence to demonstrate that the quantity of the opioids prescribed is directly correlated with postoperative consumption.31,32 Farley et al33 demonstrated that reducing the quantity of opioids prescribed following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction reduced both the duration and quantity of postoperative opioid consumption. Second, a limited, standardized opioid prescription following arthroscopic surgery has larger implications in the context of the ongoing opioid epidemic. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data, 50.5% of the 10.7 million people who misused opioids in the past year in the United States obtained them from a friend or relative.34 These results, along with the findings of the current trial, demonstrate that the prescription of additional opioids creates multiple avenues of risk to patients and society. Not only do these additional opioids have the potential for diversion or harm to children and adolescents, they may affect the patient’s opioid consumption as well. Despite surgeon concerns surrounding the potential need for patient refills with a limited opioid prescription, the results of the current study demonstrated only 2% of patients requested additional opioids after discharge. There was no significant difference in prescription refills between the opioid-sparing group and the standard care group.

Patient education has been recognized as an important pillar in postoperative opioid reduction and pain control across surgical domains.35,36,37 Within the arthroscopy literature, there is growing evidence to suggest that patient education may reduce both short-term and long-term postoperative opioid use.35,36,38

The current trial has several strengths. The study outcomes are of importance to both patients and health care systems. The blinding of both outcome assessors and data analysts safeguards against potential bias. The results were analyzed in a blinded fashion to avoid interpretation bias. The broad eligibility criteria and inclusion of the most commonly performed orthopedic surgery procedures strengthens the generalizability of the results.

Limitations

This trial has several limitations. First, given the pragmatic nature of the trial, both patients and surgeons were not blinded to the interventions, increasing the risk of bias. Second, the primary outcome relied on patient-reported opioid consumption, which carries the risk of reporting bias. Third, the subgroup analyses included small sample sizes and wide CIs, so no definitive conclusions can be made from their results. Fourth, patients underwent minimally invasive, arthroscopic surgery, so the results cannot be extrapolated to more invasive operations that are potentially more painful. Fifth, the current study excluded chronic opioid users, so the results should not be extrapolated to this patient population.

Conclusions

Among patients who underwent arthroscopic knee or shoulder surgery, a multimodal opioid-sparing postoperative pain management protocol, compared with standard opioid prescribing, significantly reduced postoperative opioid consumption over 6 weeks.

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eTable 1. List of included procedures

eFigure 1. Patient education infographic

eTable 2. Oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) conversion chart

eFigure 2. Histogram of opioid consumption by group

eFigure 3. Mean daily pain scores (VAS) over the first 14 days by group

eFigure 4. Primary outcome with subgroup analyses

eTable 3. Patient satisfaction at 2 weeks

eTable 4. Patient satisfaction at 6 weeks

Nonauthor Collaborators. NO PAin Trial Investigators

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.deShazo RD, Johnson M, Eriator I, Rodenmeyer K. Backstories on the US opioid epidemic: good intentions gone bad, an industry gone rogue, and watch dogs gone to sleep. Am J Med. 2018;131(6):595-601. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinlan J, Lobo DN, Levy N. Postoperative pain management: time to get back on track. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(S1)(suppl 1):e10-e13. doi: 10.1111/anae.14886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabatino MJ, Kunkel ST, Ramkumar DB, Keeney BJ, Jevsevar DS. Excess opioid medication and variation in prescribing patterns following common orthopaedic procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(3):180-188. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guy GP Jr, Zhang K. Opioid prescribing by specialty and volume in the US. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(5):e153-e155. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gil JA, Gunaseelan V, DeFroda SF, Brummett CM, Bedi A, Waljee JF. Risk of prolonged opioid use among opioid-naïve patients after common shoulder arthroscopy procedures. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(5):1043-1050. doi: 10.1177/0363546518819780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain NB, Peterson E, Ayers GD, Song A, Kuhn JE. US geographical variation in rates of shoulder and knee arthroscopy and association with orthopedist density. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1917315. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekhtiari S, Horner NS, Shanmugaraj A, Duong A, Simunovic N, Ayeni OR. Narcotic prescriptions following knee and shoulder arthroscopy: a survey of the Arthroscopy Association of Canada. Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7856. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner V, Gazzaniga D, Shepard M, et al. Monitoring postoperative opioid use following simple arthroscopic meniscectomy: a performance-improvement strategy for prescribing recommendations and community safety. JB JS Open Access. 2018;3(4):e0033. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.18.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar K, Gulotta LV, Dines JS, et al. Unused opioid pills after outpatient shoulder surgeries given current perioperative prescribing habits. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(3):636-641. doi: 10.1177/0363546517693665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, Horner NS, Nucci N, Dookie J, Ayeni OR. Perioperative nonopioid analgesia reduces postoperative opioid consumption in knee arthroscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;29(6):1887-1903. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06256-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniels SD, Garvey KD, Collins JE, Matzkin EG. Patient satisfaction with nonopioid pain management following arthroscopic partial meniscectomy and/or chondroplasty. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(6):1641-1647. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham H, Pickell M, Yagnatovsky M, et al. The utility of oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs compared with standard opioids following arthroscopic meniscectomy: a prospective observational study. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(3):864-870.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moutzouros V, Jildeh TR, Tramer JS, et al. Can we eliminate opioids after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(14):3794-3801. doi: 10.1177/03635465211045394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jildeh TR, Okoroha KR, Kuhlmann N, Cross A, Abbas MJ, Moutzouros V. Multimodal nonopioid pain protocol provides equivalent pain versus opioid control following meniscus surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy. 2021;37(7):2237-2245. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2021.02.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jildeh TR, Khalil LS, Abbas MJ, Moutzouros V, Okoroha KR. Multimodal nonopioid pain protocol provides equivalent pain control versus opioids following arthroscopic shoulder labral surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30(11):2445-2454. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NO PAin Investigators . Protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing a non-opioid prescription to the standard of care for pain control following arthroscopic knee and shoulder surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):1. doi: 10.1168/s12891-021-04354-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CONSORT 2010. Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. The EQUATOR Network. Updated November 25, 2021. Accessed March 19, 2022. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/consort/

- 18.Moutzouros V, Jildeh TR, Khalil LS, et al. A multimodal protocol to diminish pain following common orthopedic sports procedures: can we eliminate postoperative opioids? Arthroscopy. 2020;36(8):2249-2257. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2020.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi M, Wang L, Coroneos CJ, Voineskos SH, Paul J. Managing postoperative pain in adult outpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing codeine with NSAIDs. CMAJ. 2021;193(24):E895-E905. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.201915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.About CDC’s opioid prescribing guideline. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published March 18, 2022. Accessed March 31, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/providers/prescribing/guideline.html

- 21.Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. The visual analogue pain intensity scale: what is moderate pain in millimetres? Pain. 1997;72(1-2):95-97. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00005-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.HCAHPS: patients’ perspectives of care survey. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed November 13, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/hospitalqualityinits/hospitalhcahps

- 23.Myles PS, Myles DB, Galagher W, et al. Measuring acute postoperative pain using the visual analog scale: the minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(3):424-429. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujii MH, Hodges AC, Russell RL, et al. Post-discharge opioid prescribing and use after common surgical procedure. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(6):1004-1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.01.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thoma A, Farrokhyar F, McKnight L, Bhandari M. Practical tips for surgical research: how to optimize patient recruitment. Can J Surg. 2010;53(3):205-210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wick EC, Grant MC, Wu CL. Postoperative multimodal analgesia pain management with nonopioid analgesics and techniques: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(7):691-697. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hung CW, Riggan ND, Hunt TR III, Halawi MJ. What’s important: a rallying call for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in musculoskeletal pain: improving value of care while combating the opioid epidemic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021;104(7):659-663. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.21.00466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busse JW, Sadeghirad B, Oparin Y, et al. Management of acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):730-738. doi: 10.7326/M19-3601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ong CKS, Seymour RA, Lirk P, Merry AF. Combining paracetamol (acetaminophen) with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a qualitative systematic review of analgesic efficacy for acute postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(4):1170-1179. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cf9281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jildeh TR, Abbas MJ, Hasan L, Moutzouros V, Okoroha KR. Multimodal nonopioid pain protocol provides better or equivalent pain control compared to opioid analgesia following arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy. 2022;38(4):1077-1085. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2021.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howard R, Fry B, Gunaseelan V, et al. Association of opioid prescribing with opioid consumption after surgery in Michigan. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(1):e184234. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schroeder AR, Dehghan M, Newman TB, Bentley JP, Park KT. Association of opioid prescriptions from dental clinicians for US adolescents and young adults with subsequent opioid use and abuse. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(2):145-152. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farley KX, Anastasio AT, Kumar A, Premkumar A, Gottschalk MB, Xerogeanes J. Association between quantity of opioids prescribed after surgery or preoperative opioid use education with opioid consumption. JAMA. 2019;321(24):2465-2467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.6125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipari RN, Hughes A. In: The CBHSQ Report. How people obtain the prescription pain relievers they misuse. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; January 12, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andelman SM, Bu D, Debellis N, et al. Preoperative patient education may decrease postoperative opioid use after meniscectomy. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2019;2(1):e33-e38. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2019.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Syed UAM, Aleem AW, Wowkanech C, et al. Neer Award 2018: the effect of preoperative education on opioid consumption in patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27(6):962-967. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossi MJ. Opioid sparing through patient education programs is the future for sports medicine and arthroscopic surgery to optimize outcome. Arthroscopy. 2021;37(5):1573-1576. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2021.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheesman Q, DeFrance M, Stenson J, et al. The effect of preoperative education on opioid consumption in patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective, randomized clinical trial-2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(9):1743-1750. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eTable 1. List of included procedures

eFigure 1. Patient education infographic

eTable 2. Oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) conversion chart

eFigure 2. Histogram of opioid consumption by group

eFigure 3. Mean daily pain scores (VAS) over the first 14 days by group

eFigure 4. Primary outcome with subgroup analyses

eTable 3. Patient satisfaction at 2 weeks

eTable 4. Patient satisfaction at 6 weeks

Nonauthor Collaborators. NO PAin Trial Investigators

Data Sharing Statement