Abstract

Canavanine, the δ-oxa-analogue of arginine, is produced as one of the main nitrogen storage compounds in legume seeds and has repellent properties. Its toxicity originates from incorporation into proteins as well as arginase-mediated hydrolysis to canaline that forms stable oximes with carbonyls. So far no pathway or enzyme has been identified acting specifically on canavanine. Here we report the characterization of a novel PLP-dependent enzyme, canavanine-γ-lyase, that catalyzes the elimination of hydroxyguanidine from canavanine to subsequently yield homoserine. Homoserine-dehydrogenase, aspartate–semialdehyde–dehydrogenase and ammonium–aspartate–lyase activities are also induced for facilitating canavanine utilization. We demonstrate that this novel pathway is found in certain Pseudomonas species and the Rhizobiales symbionts of legumes. The findings broaden the diverse reactions that the versatile class of PLP-dependent enzymes is able to catalyze. Since canavanine utilization is found prominently in root-associated bacteria, it could have important implications for the establishment and maintenance of the legume rhizosphere.

A novel degradation pathway enables rhizosphere-associated bacteria to utilize canavanine.

Introduction

Non-proteinogenic amino acids represent a large group of metabolites with diverse and often unexplored functions.1 Some non-canonical amino acids act as so-called antimetabolites by mimicking proteinogenic amino acids and thereby interfere with their respective functions. l-Canavanine, or δ-oxa-arginine, serves as an antimetabolite of l-arginine. It was first discovered and isolated in 1929 from jack bean (Canavalia ensiformis)2 and further experiments revealed the structural similarity to arginine.3 The discovery a specific colorimetric reaction of pentacyanoammoniumferrate with canavanine enabled extensive surveys of its distribution among plants.4 Although the occurrence of canavanine is limited to legumes,5 a major subfamily of Fabaceae, it often serves as the main nitrogen storage compound in seeds with a content of up to ∼12% of the seeds' dry weight.6 During germination, canavanine catabolism produces canaline and urea, which are further degraded to homoserine, CO2 and ammonia.7 However, canavanine is also found in the root exudate of young plants.8,9 Interestingly, the ability to reduce canaline to homoserine and ammonia is thought to be unique to higher plants,7 opening the legume the possibility to use canavanine as a toxic repellent against herbivores and pathogens. The toxic effects of canavanine originate from the mimicry of arginine, thereby interfering with arginine metabolism and protein functions when incorporated during translation. Arginase-catalysed hydrolysis of canavanine yields canaline, which forms stable oximes with α-ketoglutarate and other carbonyl-containing compounds causing deleterious effects in the tricarboxylic acid cycle.10 Also, arginyl-tRNA synthetases are usually not able to discriminate between arginine and its antimetabolite resulting in the incorporation of canavanine into nascent polypeptide chains and in the formation of dysfunctional proteins.11,12

Some insects have adapted different strategies to circumvent canavanine toxicity. While Drosophila detects it by taste as a repulsive molecule,13 the tobacco budworm Chloridea virescens (formerly Heliothis virescens) is able to degrade canavanine by a putative, so far uncharacterized gut enzyme.11,14 In bacteria two early reports concerned with canavanine degradation reported its cleavage to homoserine and either guanidine or hydroxyguanidine but the molecular basis for this observation is unknown.15,16 We have recently become interested in the occurrence of free guanidine in nature. We and others discovered so far four different riboswitches that selectively sense guanidine in bacteria.17–21 Moreover, selective degradation pathways exist to utilize guanidine as nitrogen sources.17,22–24 Following the clarification of guanidine degradation, we are currently investigating biotic sources of guanidine and close derivatives. The present work describes the first specific canavanine degradation pathway. By enrichment on canavanine as sole carbon source we obtained a novel Pseudomonad species that is growing efficiently on canavanine as sole nitrogen and carbon source. We identified the enzymes responsible for the utilization by comparative proteomics and characterized the key reaction of canavanine degradation to be carried out by a PLP-dependent canavanine-γ-lyase. We further investigate additional enzymatic activities and the distribution of this newly described degradation pathway in the rhizosphere. In summary, canavanine is utilized efficiently by certain legume-associated bacteria. The plant-based synthesis of canavanine and its specific utilization by certain root-associated bacteria could contribute to shaping the composition of the rhizosphere.

Results

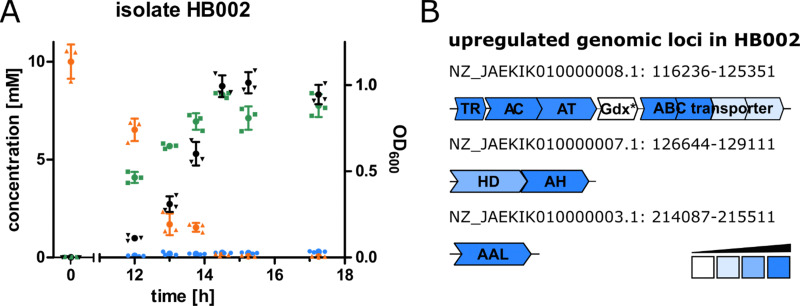

Enrichment of canavanine-degrading bacteria

For the purpose of isolating bacteria able to degrade canavanine, we collected rhizosphere soil samples of the legume Phaseolus coccineus (runners bean) and isolated bacterial strains that were able to grow on minimal medium plates containing canavanine as sole carbon source. In order to differentiate between bacteria involuntarily using canavanine via the already reported arginase-mediated hydrolysis to canaline and urea and bacteria producing guanidine or hydroxyguanidine we further cultivated bacterial isolates in liquid medium and analysed culture supernatants by mass spectrometry (MS) for guanidine and hydroxyguanidine contents. Interestingly, upon growth on 10 mM canavanine as carbon source most isolates produced only small amounts of guanidine (<500 μM in the supernatant), while accumulating hydroxyguanidine in concentrations up to 8 mM (Fig. 1A). The increase of hydroxyguanidine correlates with the decrease of canavanine, suggesting a cleavage of canavanine to hydroxyguanidine and homoserine, as it has been observed for the tobacco budworm.14 In a further experiment we omitted ammonium salts as nitrogen source in order to evaluate whether canavanine can serve as sole nitrogen source as well. Isolate HB002 was able to grow on M8 minimal salt medium with canavanine as sole carbon and nitrogen source and we did not observe any differences in optical densities or in accumulated amounts of hydroxyguanidine (Fig. S1, ESI†).

Fig. 1. (A) Concentration of canavanine (orange), guanidine (blue) and hydroxyguanidine (green) in the supernatant of isolate HB002 grown on 10 mM canavanine as sole carbon source in M9 minimal medium, values represent the mean of triplicates measured over time, optical density of the corresponding cultures is shown in black, n = 3, error bars = SD. (B) Genomic loci of induced proteins (located in the genome of HB002, NCBI accession number JAEKIK000000000) in isolate HB002 upon growth on canavanine compared to growth on glycerol. Except for HD and two of the ABC transporter units all proteins shown were only detected in the canavanine-grown sample. Abbreviations: TR: transcriptional regulator, AC/AH: aldehyde dehydrogenases, AT: class I/II aminotransferase, Gdx: guanidine exporter (*not detected in the proteome analysis), ABC: ATP binding cassette, HD: homoserine dehydrogenase, AAL: ammonium aspartate lyase.

The bacterial sample with the highest guanidine and hydroxyguanidine levels (isolate HB002) was further investigated. Based on 16S rRNA gene analysis, genome sequencing (DDBJ/ENA/GenBank accession number JAEKIK000000000), digital DNA–DNA hybridization, average nucleotide identity, and phenotypic description, we identified the isolated canavanine-degrading bacterium as a novel species belonging to the genus Pseudomonas. We named the bacterium Pseudomonas canavaninivorans (HB002T = DSM 112525T = LGM 32336T) for its ability to grow on canavanine as sole C- and N-source. A detailed phenotypic and taxonomic characterization of P. canavaninivorans is described elsewhere.25

Analysis of canavanine-dependent gene expression

In order to examine the genes involved in canavanine degradation P. canavaninivorans was either grown on canavanine or glycerol as sole carbon source and differences in protein expression levels were detected by comparative proteome analysis. Among the 1610 proteins identified (Table S1, ESI†) 45 were only expressed upon growth on canavanine. Of those 45 proteins, seven cluster together in the same genetic locus. Among those proteins is a class I/II PLP-dependent aminotransferase (MBJ2347155.1, further referred to as AT) and an aldehyde dehydrogenase (MBJ2347154.1, further referred to as AC) which cluster together with a transcription factor, a guanidine exporter26 (MBJ2347156.1, further referred to as Gdx) and four subunits of an ATP-binding cassette-type transporter (MBJ2347157.1-MBJ2347160.1, further referred to as ABC transporter) (Fig. 1B). In addition, we found a highly upregulated homoserine-dehydrogenase (MBJ2346999.1, further referred to as HD) with yet another aldehyde-dehydrogenase (MBJ2347000.1, further referred to as AH) clustering together and at a separate locus an aspartate–ammonia–lyase (MBJ2345991.1, further referred to as AAL) (Fig. 1B). We speculated that the potential operon in conjunction with the other enzymes is enabling P. canavaninivorans to utilize canavanine as sole carbon source, as they were amongst the most abundant proteins found in the canavanine-grown sample.

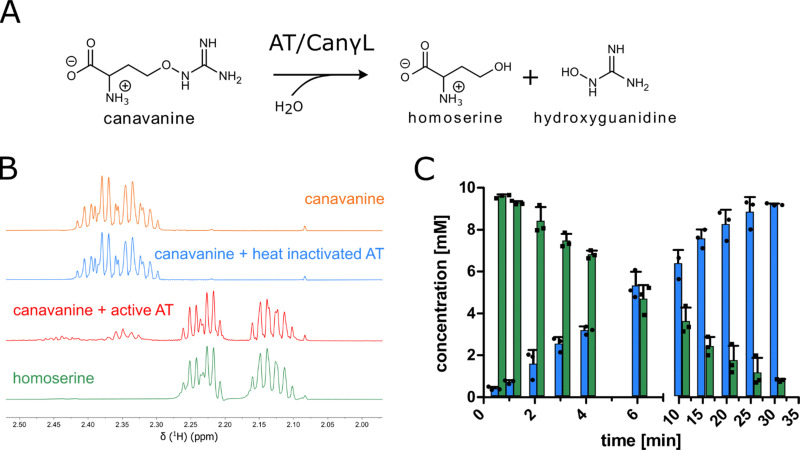

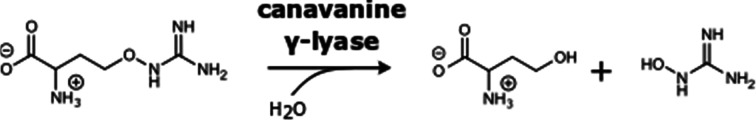

As a key enzyme in canavanine degradation we suspected the class I/II PLP-dependent aminotransferase (AT), because individuals of this general class of enzymes are known to catalyze a variety of different reactions with amino acid substrates ranging from decarboxylation, racemization and transamination to replacement and elimination reactions.27 In order to gain more insight into potential reactions performed by the PLP-dependent AT, we performed an advanced sequence search against the RCSD protein data bank. The most similar hit was a methionine-γ-lyase (MγL) of Clostridium sporonges.28 We speculated that in analogy to MγL, the identified AT could catalyze the elimination of hydroxyguanidine from canavanine with a subsequent water addition to yield homoserine as additional product (Fig. 2A). In order to test whether AT catalyzes the proposed reaction, we overexpressed purified enzyme the enzyme in E. coli.

Fig. 2. (A) Proposed reaction catalyzed by aminotransferase AT (MBJ2347155.1). (B) 1H-proton NMR spectra of reactions with purified AT showing the conversion of canavanine to homoserine (for complete spectra see item 1, ESI†). (C) MS concentration measurements of canavanine (green) and hydroxyguanidine (blue) in a reaction with purified AT, n = 3, error bars = SD, each data point represents the mean of a technical triplicate.

Characterization and reaction mechanism of canavanine-γ-lyase

In a first experiment the aminotransferase (AT) was incubated with canavanine and the reaction was investigated using proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry (1H-NMR) and MS. Canavanine was converted to homoserine in an enzyme- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2A, ESI†). No changes in canavanine peak intensities were observed when AT was heat-inactivated prior to the reaction (Fig. 2B, blue spectrum), while with active enzyme after one hour the majority of canavanine was converted to homoserine (Fig. 2B, red spectrum). Furthermore, in consistency with the in vivo growth experiment (Fig. 1A) MS measurements of reactions with purified AT revealed an increase of hydroxyguanidine with a simultaneous decrease of canavanine over time (Fig. 2C). 1H-NMR also showed the formation of small amounts (<5% of product) of 2-oxobutanoate and ammonium (Fig. S3, ESI†), which is in accordance with a potential β,γ-elimination mechanism. For the methionine-γ-lyase-catalyzed reaction of methionine it has been shown before that 2-oxobutanoate and ammonium occur as products.29,30 In the case of the newly identified AT, this reaction only seems to take place as a side reaction and homoserine is found as main product.

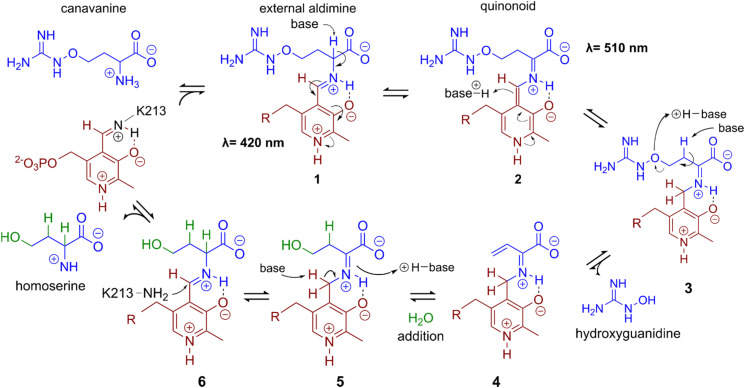

In order to shed light on the reaction mechanism of the AT, we performed a hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange experiment. In case the reaction involves the addition of water to the unsaturated bond at the β,γ-position, carrying out the reaction in D2O should lead to changes in some of the signals of homoserine recorded in the 1H-decoupled 13C-NMR experiment. Specifically, we expected a change of multiplicity for the signal assigned to the carbon atoms in the α and β position as a result of the incorporation of deuterium into the molecule. Indeed, the obtained 13C-NMR data confirmed our hypothesis as the signals assigned to the α and β carbon atoms changed their multiplicity from singlet to triplet with equally intense peaks (Fig. S4, ESI†). This outcome can be explained by the inclusion of a deuterium atom at the two positions which also confirms the protonation event from solvent D2O in the last imine isomerization. The experiments let us conclude that the identified AT is a canavanine-γ-lyase (CanγL) and allowed to suggest a likely reaction route (Scheme 1). First, canavanine reacts to form aldimine (1) between the alpha amino group of canavanine and the cofactor pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) formerly bound to an internal lysine. Then, protonation/deprotonation results in formation of quinonoid (2) and canavanine ketamine (3) followed by the elimination of hydroxyguanidine from the β- and γ-positions to yield the unsaturated vinylglycine ketamine intermediate (4). Next, water adds to the double bond in the β,γ-position forming the imine equivalent of homoserine (5). Imine isomerization to form the homoserine aldimine (6) and reaction with the internal CanγL-lysine residue results in the release of the product homoserine. Alternatively, if release of the vinylglycine ketimine (4) from PLP takes place before water addition the reaction likely follows the described mechanism of methionine-γ-lyase29,30 to yield 2-oxobutanoate and ammonium, thereby explaining the formation of small quantities of these products (Fig. S3, ESI†).

Scheme 1. A potential reaction mechanism of canavanine-γ-lyase: starting with free canavanine, PLP-canavanine aldimine (1) formation, quinonoid (2) formation, canavanine ketimine (3) formation, elimination of hydroxyguanidine resulting in vinylglycine ketimine (4), water addition yielding homoserine ketimine (5), homoserine aldimine (6) formation, and release of homoserine by reformation of PLP-imine with the internal lysine. Wavelengths indicate UV-Vis maxima in UV-Vis data shown in Fig. S8 (ESI†) next to reaction intermediates that could potentially cause the observed absorption.

Next, we characterized the substrate specificity of canvanine-γ-lyase (CanγL) with the canavanine analogue arginine as well as substrates of the mechanistically related enzymes methionine- and cystathionine-γ-lyase. We did not detect any turnover with arginine nor using the substrates methionine and cystathionine monitored by 1H-NMR (Fig. S5, ESI†), concluding that CanγL is highly specific for canavanine degradation. Further experiments at different pHs and temperatures revealed a pH optimum of CanγL between pH 6.9 and 8.0 and an optimal reaction temperature between 34.8 and 37 °C (Fig. S2B and C, ESI†) which is similar to reported values for the related enzyme methionine-γ-lyase.31,32 A kinetic characterization of CanγL was carried out by coupling the cleavage reaction of canavanine to the upregulated homoserine-dehydrogenase (HD) which catalyzes the conversion of homoserine and NAD+ to aspartate–semi-aldehyde and NADH. The production of NADH was monitored spectrophotometrically. HD was added in 20-fold access over CanγL to ensure that the CanγL-catalyzed step is rate-limiting (Fig. S5A, ESI†). Plotting the initial velocities over the substrate concentration allowed us to calculated KM and kcat. CanγL converts canavanine with a KM of 590 ± 20 μM and a kcat of 1.34 ± 0.01 s−1.

To confirm the involvement of PLP as a cofactor we then mutated the predicted active site lysine (K213), which is responsible for PLP binding, to alanine and evaluated the mutational effect on the reaction by NADH formation. The mutation K213A completely abolished enzymatic activity as NADH formation of K213A with 25 mM canavanine was similar to the background reaction of wild-type CanγL without addition of the substrate canavanine (Fig. S7, ESI†). Additionally, we recorded UV/Vis spectra of an enzyme reaction since the PLP aldimine and quinonoid intermediates give rise to characteristic peaks.33,34 Time-dependent increase of presumed aldimine and quinonoid peaks were observed for the wt enzyme whereas a K213A mutant of the enzyme did not show time-dependent changes in peak intensities, see Fig. S8 (ESI†).

PLP-dependent enzymes are found in several different protein families and fold classes. In order to gain an insight into the structure and fold type of the enzyme, we submitted the primary sequence of CanγL to alpha-fold35–39 and superimposed the resulting model (Fig. S9A, ESI†) with the structure of methionine-γ-lyase (MγL) from Clostridium sporonges (PDB code: 5DX5 chain A), as this enzyme represented the closest match in the RSCB protein data bank. The overall fold and structure of CanγL is very similar to MγL (Fig. S9B, ESI†), especially in the PLP-binding domain, which assigns the CanγL to the type I-fold architecture of PLP-dependent enzymes. The CanγL PLP domain contains the typical seven stranded mainly parallel β-sheet with +−+++++ directions of the β-strands, which are flanked by seven α-helices on both sides of the β-sheet.28,40 Also the PLP-binding lysine K213 aligned well with K212 of MγL (Fig. S9C, ESI†). The superimposed model is added as a supplementary PYMOL file (ESI†).

Finally, to validate the proposed role of canavanine-γ-lyase in canavanine assimilation we created deletion strains via homologous recombination. CangL was deleted together with a second gene annotated as B3/4 domain-like protein (MBJ2347151.1) which we suspect to have an involvement in canavanine metabolism as it was also highly upregulated in our proteome data and its position in vicinity to the canavanine degradation operon. The deletion of CanγL rendered the strain unable to grow on canavanine as sole carbon source while its growth on glucose was not affected (Fig. S10, ESI†). A single deletion strain of the B3/4 domain already resulted in a strong reduction of growth on canavanine, a finding we have planned to address in future experiments. Taken together, our findings describe a novel enzyme acting efficiently and specifically on canavanine by a PLP-dependent β/γ-elimination/addition mechanism yielding the two products homoserine and hydroxyguanidine.

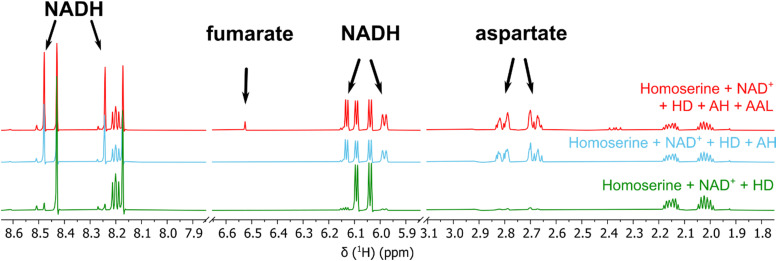

Characterization of homoserine-dehydrogenase, aldehyde-dehydrogenases and ammonium-aspartate-lyase

Next, we tested whether the enzymatic activity of homoserine-dehydrogenase (HD), aldehyde-dehydrogenase 1 (AH, same operon as HD), aldehyde-dehydrogenase 2 (AC, same operon as CanγL) and ammonium–aspartate–lyase (AAL) would lead to the formation of fumarate since this set of enzymes should enable P. canavaninivorans to utilize homoserine via aspartate semialdehyde and aspartate yielding fumarate.41 Indeed, when combining purified HD with either of the two aldehyde-dehydrogenases AH or AC and AAL the formation of fumarate via aspartate was observed (Fig. 3 and Fig. S11, ESI†). Pairwise sequence alignment of AH and AC by EMBOSS Needle42 showed 67.4% identity between the two oxidoreductases. Moreover, in the genomic context of P. brassicacearum 3Re2-7 and P. fluorescens F113, close relatives of P. canavaninivorans, the corresponding homolog of HD is found in the same genetic locus as CanγL and AC. Considering these findings, we suggest that the aldehyde-dehydrogenases AH and AC have redundant functions and that in P. canavaninivorans a gene duplication and reorganization event has split apart the complete canavanine degradation operon present in other Pseudomonads into two separate genomic loci.

Fig. 3. 1H-NMR of the reaction of homoserine to fumarate via homoserine dehydrogenase (HD), aldehyde dehydrogenases (AH) and ammonium–aspartate–lyase (AAL). The reaction with aldehyde dehydrogenase AC and the corresponding reference spectra are shown in Fig. S7 (ESI†).

We also observed that the reaction of HD was only dependent on the cofactor NAD+ and that HD showed no activity utilizing NADP+ (Fig. S6B, ESI†). Comparing the sequence of HD to a recently discovered class of homoserine-dehydrogenases showed moderate sequence identity (59.6%).43 Members of this new class favour the oxidation of homoserine rather than the reverse reaction taking place in the last step of the homoserine biosynthesis. The identified HD also displays the reported change in the NAD(P)+ binding motif, explaining why HD rejects NADP+ as co-substrate. In conclusion, we have reconstituted the whole pathway from canavanine to fumarate shown in Fig. 4 using purified enzymes.

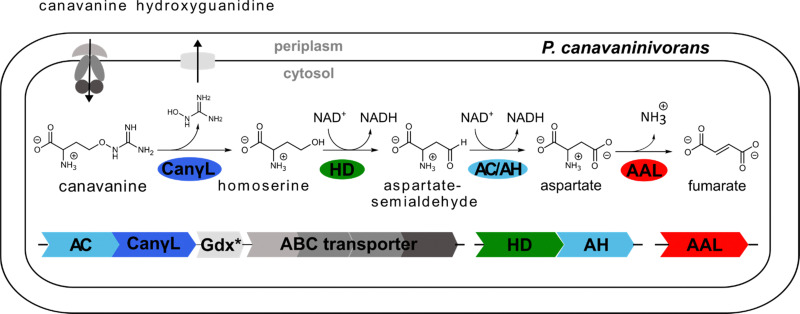

Fig. 4. Novel canavanine degradation pathway in P. canavaninivorans. AC/AH: aldehyde dehydrogenase, CanγL: canavanine-γ-lyase, Gdx: guanidine exporter, ABC: ATP-binding cassette type transporter, HD: homoserine dehydrogenase, AAL: ammonium–aspartate–lyase. Color indicates that the enzymatic function was experimentally validated in this work.

Distribution of canvanine-γ-lyase in prokaryotic genomes

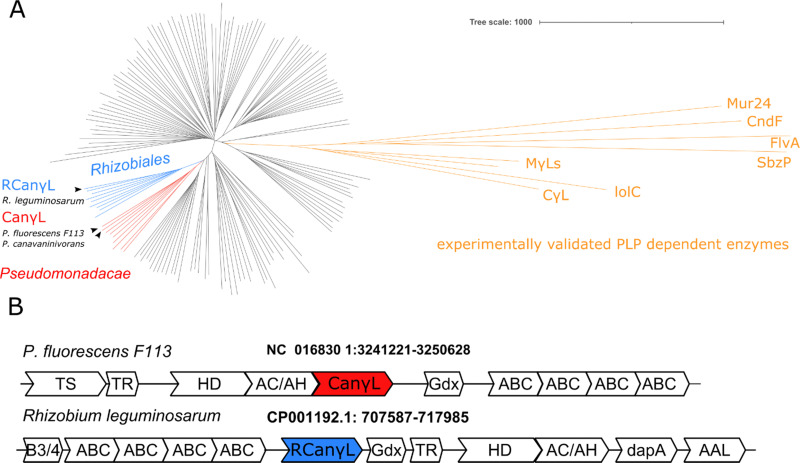

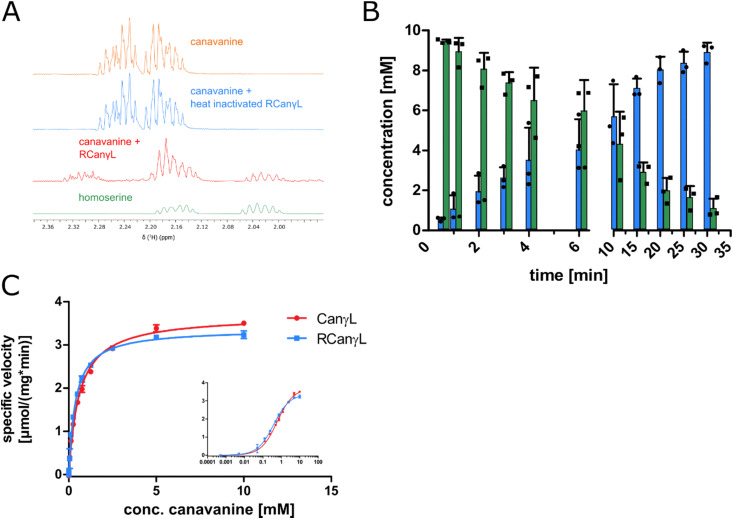

In order to identify the occurrence of the canavanine degradation activity in other bacteria we performed a neighbor-joining phylogeny search based on canvanine-γ-lyase (CanγL) using the Consurf platform44 and the BLOSUM62 algorithm45 and visualized the result using iTOL v6 (Fig. 5A).46 The novel CanγL enzyme (red) is clearly distant to other validated PLP-dependent enzymes like cystathionine-γ-lyase or methionine-γ-lyase (orange). The most similar homologs to the identified CanγL were found in other Pseudomonads (red) and in Rhizobiales (blue). Furthermore, when we compared the genomic contexts of the CanγL homologs, only in the genera Pseudomonas and Rhizobium the homologs clustered together with homologs of the additional enzymes of the pathway (HD, AC/AH, ABC transporters and Gdx) (Fig. 5B). In Rhizobiales genes coding for AAL and another enzyme (dapA) involved in aspartate semialdehyde metabolism are located at the same genetic locus. To test whether the CanγL homologs identified in Rhizobiales are indeed catalyzing the same reaction we overexpressed the respective enzyme of Rhizobium leguminosarum (WP_012555980.1) in E. coli and investigated canavanine degradation of the purified enzyme as described before. The rhizobial CanγL (RCanγL) also led to the formation of homoserine (Fig. 6A) and hydroxyguanidine (Fig. 6B) from canavanine. With a KM of 390 ± 13 μM and a kcat of 1.23 ± 0.011 s−1 RCanγL displayed kinetic parameters similar to CanγL. Both reactions fitted well to Michaelis–Menten-kinetics (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 5. (A) Phylogenetic distribution of CanγL based on a homology search. Only for Pseudomonadacae (red) and Rhizobiales (blue) (R)CanγL is found co-localized with genes shown in (B). Black clades represent homology-inferred representatives annotated as MγLs, CγLs and other PLP-dependent enzymes. In orange experimentally validated PLP-dependent enzymes are shown, see discussion. (B) Representatives of the predominant genomic loci of the novel canavanine degradation pathway in Pseudomonadacae and Rhizobiales. Gene annotations: TS: threonine synthase, TR: transcriptional regulator, HD: homoserine dehydrogenase, AC/AH: aldehyde dehydrogenase, AT: aminotransferase (CanγL), Gdx: guanidinium exporter, ABC: importer system, B3/4: potential tRNA editing domain, dapA: 4-hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate synthase, AAL: ammonium–aspartate–lyase.

Fig. 6. (A) 1H-proton NMR spectra of a reaction of canavanine to homoserine catalyzed by purified rhizobial canavanine-γ-lyase (RCanγL, WP_012555980.1), representative peaks shown, complete spectra can be found in item 2 (ESI†). (B) MS concentration measurements of canavanine (green) and hydroxyguanidine (blue) in a reaction with purified RCanγL, n = 3, error bars = SD, each data point represents the mean of a technical triplicate. (C) Comparison of the kinetics of CanγL and RCanγL. The inlet shows the data with a log 10 scale of substrate concentration, n = 3, error bars = SD.

Discussion

In this work we identified Pseudomonas canavaninivorans sp. nov. that is able to utilize canavanine as sole carbon and nitrogen source. We demonstrated that a set of proteins upregulated upon growth on canavanine composes the first degradation pathway acting specifically on canavanine. The key enzyme, a canavanine-γ-lyase, converts canavanine to homoserine by a PLP-dependent elimination of hydroxyguanidine resulting in a β,γ-unsaturated vinylglycine ketamine intermediate. This intermediate is characteristic for PLP-dependent enzymes of the cystathionine-γ-lyase family although different reaction paths are possible from here.47 For example, in methionine-γ-lyases it leads to the formation of 2-oxobutanoate,29 while in the cystathionine-γ-lyase family-related enzymes CndF48 and FlvA49 vinylglycine ketimine reacts as a Michael acceptor with a C-nucleophile. Reactions with N-nucleophiles (lolC,50 Mur2451) and S-nucleophiles (cystathionine-synthase,52O-acetylhomoserine-sulfhydrylase53) have been reported as well. Recently, the enzyme SbzP from Streptomyces species was described that catalyses Cγ activation with reversed reactivity via an intermediary β,γ-unsaturated quinonoid attacking C4 of the pyridinium ring of β-NAD acting as electrophile.34 In case of the canavanine-γ-lyase described here, water is added, resulting in the formation of homoserine. Given the large number of so-far uncharacterized PLP-dependent enzymes with relatively high similarity (Fig. 5A) it seems likely that other so-far unrecognized reactions are catalyzed by members of this versatile enzyme class.

The canavanine degradation operon described here facilitates the oxidation of released homoserine to aspartate–semi-aldehyde by a member of a recently discovered new class of homoserine-dehydrogenases,43 followed by oxidation to aspartate by either one of the two aldehyde-dehydrogenases (AC/AH) found induced by canavanine. Then, an ammonium-aspartate-lyase converts aspartate to fumarate and ammonia. The ABC transporter found in the same operon as CanγL likely functions as a canavanine importer. Since periplasmic substrate-binding proteins are only found associated with importers in bacteria,54 the ABC transporter facilitates the uptake of a substrate. In addition, the substrate-binding domain-containing protein of the upregulated transporter (MBJ2347157.1) is a homolog of an already described arginine-, lysine- and ornithine-binding domain-containing protein of Salmonella enterica (WP_079987354.1, 43.5% identity).

The guanidine exporter Gdx also present in the operon likely functions as a hydroxyguanidine exporter since it has been demonstrated recently that Gdx not only efficiently exports guanidine but also amino- and methylguanidine.26 We observed in the growth experiments with 10 mM canavanine as substrate that hydroxyguanidine is almost stoichiometrically exported with 8 mM measured in the supernatant, even when canavanine serves as the only nitrogen source. The canavanine cleavage product homoserine should be sufficient for supporting growth because the nitrogen from the alpha-amino group in homoserine satisfies the bacterial biomass need with a carbon : nitrogen ratio of 4 : 1.55,56 This explains why the majority of hydroxyguanidine is exported and not used by the bacterium for nitrogen assimilation as we have demonstrated recently for guanidine.24

The homology search of the canavanine-γ-lyase revealed that the enzyme is also found in Rhizobiales. We confirmed that the CanγL homolog of R. leguminosarum is indeed degrading canavanine. We found CanγL co-occurring in the same genomic locus with the other enzymes of the described canavanine degradation pathway only in the genera of Pseudomonas and Rhizobiales. The pathway therefore most likely represents an adaptation to the vicinity of legumes as canavanine is thought to be restricted to these plants.6,7,57 Adding to this picture, it has been shown that the legume Glycyrrhiza uralensis exudes canavanine in order to support symbiotic events with rhizobia.8 The authors of the study showed that canavanine induces the expression of the canavanine exporter MsiA in Mesorhizobium tianshanense, which confers canavanine resistance. P. canavaninivorans also contains a homolog of MsiA (MBJ2350238.1, 40.0% identity, 58.0% similarity), suggesting that certain bacteria might have at least two ways for coping with canavanine: by degrading and/or exporting it. This finding also emphasizes the association of P. canavaninivorans with the canavanine-rich legume rhizosphere.

Recently, studying hairy vetch (Vicia villosa) it was shown that canavanine is exudated by the roots during early plant development impacting the composition and metabolic activity of the microbial soil community.9 Furthermore, it was demonstrated for Sinorhizobium meliloti that canavanine shuts down the production of the exopolysaccharide EPSII without affecting the growth of the bacterium,58 which has been reported to be a crucial step in the process of nodule invasion.59 Hence, canavanine exudated by legume plants could support nodulation and infection during root development. Canavanine could thereby act both as a signaling molecule for the free-living bacterium to onset its symbiosis with the legume plant as well as serve as a nutrient for both symbiotic and non-symbiotic bacteria in the rhizosphere. S. meliloti also contains a homolog of CanγL (WP_100674444.1, 71.0% identity) in the genetic context of the utilization pathway presented in this work (see operon structure R. leguminosarumFig. 5B).

The finding that the canavanine-γ-lyase deletion strain of P. canavaninivorans was unable to grow on canavanine represents additional evidence that the genes described in this work indeed compose a canavanine degradation operon. In addition, the poor growth of the B3/4 domain-protein deletion strain raises further questions regarding the function of this protein and its connection to canavanine metabolism. Interestingly, B3/4 domain-containing genes are often found regulated by guanidine riboswitches.20,21 Their homology to domains annotated as aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase editing domains suggest a role in mediating canavanine toxicity originating from misincorporation into proteins.

Even more speculative, canavanine could also play a potential role in establishing the metabolic relationship of the plant and its Rhizobia in analogy to a recently published co-catabolism of arginine and succinate in symbiotic nitrogen fixation.60 The authors found that plants supply not only succinate but also arginine to the nitrogen-fixing bacteria which finally benefits the plant with higher nitrogen yields and the bacteroid with facilitated respiration under the highly acidic conditions present within the symbiosome. Canavanine degradation could be used by the bacterium in a similar fashion to arginine, as the processing of the carbon skeleton would also generate reductive power in form of NADH. Also, recent studies indicate that co-inoculation of Rhizobia with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria like certain pseudomonads results in larger nitrogen fixation and better growth of the respective legume host under several stress conditions.61–63 Additionally, it was just currently shown for the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, that commensal Pseudomonas can protect the plant against very closely related pathogenic Pseudomonads and that the host environment indeed affects the microbe–microbe interactions.64 Taken together, modulating the microbiome by offering canavanine and thereby attracting Rhizobia and other plant growth-promoting bacteria capable of utilizing canavanine may foster symbiotic events and help shaping a favorable rhizosphere.

Conclusions

The arginine-mimicking legume metabolite canavanine can be degraded and utilized as sole carbon and nitrogen source by rhizosphere-associated bacteria. The first specific canavanine degradation pathway is comprised of canavanine-γ-lyase as key activity, yielding homoserine and hydroxyguanidine. Further activities are responsible for channeling homoserine into the TCA, importing canavanine and exporting hydroxyguanidine. The finding of a specific canavanine degradation pathway should contribute to a better understanding of the interactions between legumes and associated bacteria, an important task given the role legumes play in global food security.

Experimental procedure

The experimental procedure can be found in the supplementary material of this manuscript.

Author contributions

FH and JSH conceived the project and planned all experiments. FH and HB carried out the P. canavaninivorans enrichment, its initial characterization, enzyme purifications and the enzymatic assays. FH and MS conducted and evaluated the NMR analyses of the enzyme reactions. FH measured UV/Vis spectra and performed the homology and modelling calculations. The manuscript was written by FH and JSH with contributions from all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding sources

European Research Council – ERC CoG 681777.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

JSH acknowledges funding from the ERC CoG “RiboDisc”. We thank Anke Friemel from the University of Konstanz NMR facility and Dmitry Galetsky and Astrid Joachimi for technical assistance and Lena Barra for helpful discussions. We kindly thank Prof. Herbert Schweizer (University of Florida, USA) for providing the pEX18Gm suicide vector.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d2cb00128d

References

- Fichtner M. Voigt K. Schuster S. The tip and hidden part of the iceberg: Proteinogenic and non-proteinogenic aliphatic amino acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj. 2017;1861:3258–3269. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M. Tomiyama T. A new amino-compound in the jack bean and a corresponding new ferment.(l)*. J. Biochem. 1929;11:265–271. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a125044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M. Yamada H. Studies on a di-amino acid, canavanin (II) J. Biochem. 1932;16:339–350. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a125217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon W. R. Bell E. A. Canavanine: detection and occurrence in Colutea arborescens. Biochem. J. 1955;59:221–224. doi: 10.1042/bj0590221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal G. A. The biological effects and mode of action of L-canavanine, a structural analogue of L-arginine. Q. Rev. Biol. 1977;52:155–178. doi: 10.1086/409853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal G. A. Nitrogen allocation for L-Canavanine synthesis and its relationship to chemical defense of the seed. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1977;5:219–220. doi: 10.1016/0305-1978(77)90007-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal G. A. Metabolism of l-Canavanine and l-Canaline in Leguminous Plants. Plant Physiol. 1990;94:1–3. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai T. Cai W. Zhang J. Zheng H. Tsou A. M. Xiao L. Zhong Z. Zhu J. Host legume-exuded antimetabolites optimize the symbiotic rhizosphere. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;73:507–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardani-Korrani H. Nakayasu M. Yamazaki S. Aoki Y. Kaida R. Motobayashi T. Kobayashi M. Ohkama-Ohtsu N. Oikawa Y. Sugiyama A. Fujii Y. L-Canavanine, a Root Exudate From Hairy Vetch (Vicia villosa) Drastically Affecting the Soil Microbial Community and Metabolite Pathways. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:701796. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.701796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A. J. Oxime formation between α-keto acids and l-canaline. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1984;233:603–610. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melangeli C. Rosenthal G. A. Dalman D. L. The biochemical basis for L-canavanine tolerance by the tobacco budworm Heliothis virescens (Noctuidae) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:2255–2260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal G. A. Dahlman D. L. L-Canavanine and protein synthesis in the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1986;83:14–18. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitri C. Soustelle L. Framery B. Bockaert J. Parmentier M.-L. Grau Y. Plant insecticide L-canavanine repels Drosophila via the insect orphan GPCR DmX. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge M. A. Rosenthal G. A. Dahlman D. L. Tobacco budworm, Heliothis virescens [Noctuidae] resistance to l-canavanine, a protective allelochemical. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1986;25:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0048-3575(86)90005-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara H. Prescott J. M. Snell E. E. The bacterial cleavage of canavanine to homoserine and guanidine, The. J. Biol. Chem. 1955;217:497–503. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)57198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyankar G. D. Ikawa M. Snell E. E. The enzymatic cleavage of canavanine to homoserine and hydroxyguanidine. J. Biol. Chem. 1958;233:1175–1178. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)77362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J. W. Atilho R. M. Sherlock M. E. Stockbridge R. B. Breaker R. R. Metabolism of Free Guanidine in Bacteria Is Regulated by a Widespread Riboswitch Class. Mol. Cell. 2017;65:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock M. E. Breaker R. R. Biochemical Validation of a Third Guanidine Riboswitch Class in Bacteria. Biochemistry. 2017;56:359–363. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock M. E. Malkowski S. N. Breaker R. R. Biochemical Validation of a Second Guanidine Riboswitch Class in Bacteria. Biochemistry. 2017;56:352–358. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenkeit F. Eckert I. Hartig J. S. Weinberg Z. Discovery and characterization of a fourth class of guanidine riboswitches. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:12889–12899. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvail H. Balaji A. Yu D. Roth A. Breaker R. R. Biochemical Validation of a Fourth Guanidine Riboswitch Class in Bacteria. Biochemistry. 2020;59:4654–4662. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funck D. Sinn M. Fleming J. R. Stanoppi M. Dietrich J. López-Igual R. Mayans O. Hartig J. S. Discovery of a Ni2+-dependent guanidine hydrolase in bacteria. Nature. 2022;603:515–521. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04490-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider N. O. Tassoulas L. J. Zeng D. Laseke A. J. Reiter N. J. Wackett L. P. Maurice M. S. Solving the Conundrum: Widespread Proteins Annotated for Urea Metabolism in Bacteria Are Carboxyguanidine Deiminases Mediating Nitrogen Assimilation from Guanidine. Biochemistry. 2020;59:3258–3270. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinn M. Hauth F. Lenkeit F. Weinberg Z. Hartig J. S. Widespread bacterial utilization of guanidine as nitrogen source. Mol. Microbiol. 2021;116(1):200–210. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauth F. Buck H. Hartig J. S. Pseudomonas canavaninivorans sp. nov., isolated from bean rhizosphere. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022;72(1) doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.005203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermani A. A. Macdonald C. B. Gundepudi R. Stockbridge R. B. Guanidinium export is the primal function of SMR family transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:3060–3065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719187115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J. Han Q. Tan Y. Ding H. Li J. Current Advances on Structure-Function Relationships of Pyridoxal 5'-Phosphate-Dependent Enzymes. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019;6:4. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revtovich S. Anufrieva N. Morozova E. Kulikova V. Nikulin A. Demidkina T. Structure of methionine γ-lyase from Clostridium sporogenes. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. F: Struct. Biol. Commun. 2016;72:65–71. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X15023869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato D. Shiba T. Karaki T. Yamagata W. Nozaki T. Nakazawa T. Harada S. X-Ray snapshots of a pyridoxal enzyme: a catalytic mechanism involving concerted 1,5-hydrogen sigmatropy in methionine γ-lyase. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:4874. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05032-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato D. Nozaki T. Methionine gamma-lyase: the unique reaction mechanism, physiological roles, and therapeutic applications against infectious diseases and cancers. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/iub.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faleev N. G. Alferov K. V. Tsvetikova M. A. Morozova E. A. Revtovich S. V. Khurs E. N. Vorob'ev M. M. Phillips R. S. Demidkina T. V. Khomutov R. M. Methionine gamma-lyase: mechanistic deductions from the kinetic pH-effects. The role of the ionic state of a substrate in the enzymatic activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1794:1414–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafkenscheid J. C. Kohler B. E. Effects of temperature on measurement of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase in commercial control sera. Clin. Chem. 1986;32:184–185. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/32.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins B. G. Bastin B. Yang C. Neubauer T. J. Young R. P. Hilario E. Huang Y. M. Chang C. A. Fan L. Dunn M. F. Marsella M. J. Mueller L. J. Protonation states of the tryptophan synthase internal aldimine active site from solid-state NMR spectroscopy: direct observation of the protonated Schiff base linkage to pyridoxal-5'-phosphate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:12824–12827. doi: 10.1021/ja506267d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barra L. Awakawa T. Shirai K. Hu Z. Bashiri G. Abe I. β-NAD as a building block in natural product biosynthesis. Nature. 2021;600:754–758. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirdita M. Schütze K. Moriwaki Y. Heo L. Ovchinnikov S. Steinegger M. ColabFold: Making Protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods. 2022;19:679–682. doi: 10.1038/s41592-022-01488-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirdita M. Steinegger M. Söding J. MMseqs2 desktop and local web server app for fast, interactive sequence searches. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:2856–2858. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirdita M. von den Driesch L. Galiez C. Martin M. J. Soding J. Steinegger M. Uniclust databases of clustered and deeply annotated protein sequences and alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D170–D176. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A. L. Almeida A. Beracochea M. Boland M. Burgin J. Cochrane G. Crusoe M. R. Kale V. Potter S. C. Richardson L. J. Sakharova E. Scheremetjew M. Korobeynikov A. Shlemov A. Kunyavskaya O. Lapidus A. Finn R. D. MGnify: the microbiome analysis resource in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D570–D578. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper J. Evans R. Pritzel A. Green T. Figurnov M. Ronneberger O. Tunyasuvunakool K. Bates R. Z’idek A. Potapenko A. Bridgland A. Meyer C. Kohl S. A. A. Ballard A. J. Cowie A. Romera-Paredes B. Nikolov S. Jain R. Adler J. Back T. Petersen S. Reiman D. Clancy E. Zielinski M. Steinegger M. Pacholska M. Berghammer T. Bodenstein S. Silver D. Vinyals O. Senior A. W. Kavukcuoglu K. Kohli P. Hassabis D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansonius J. N. Structure, evolution and action of vitamin B6-dependent enzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1998;8:759–769. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(98)80096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk G., Bacterial Metabolism, Springer New York, New York, NY, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- Rice P. Longden I. Bleasby A. EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–277. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. Deng H. Bai Y. Fan T.-P. Zheng X. Cai Y. Characterization of a Novel Type Homoserine Dehydrogenase Only with High Oxidation Activity from Arthrobacter nicotinovorans. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.02.09.430557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landau M. Mayrose I. Rosenberg Y. Glaser F. Martz E. Pupko T. Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2005: the projection of evolutionary conservation scores of residues on protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W299–W302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S. Henikoff J. G. Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:10915–10919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I. Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W293–W296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzović P. Holbrook E. L. Greene R. C. Dunn M. F. Reaction mechanism of Escherichia coli cystathionine gamma-synthase: direct evidence for a pyridoxamine derivative of vinylglyoxylate as a key intermediate in pyridoxal phosphate dependent gamma-elimination and gamma-replacement reactions. Biochemistry. 1990;29:442–451. doi: 10.1021/bi00454a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. Liu C.-T. Tang Y. Discovery and Biocatalytic Application of a PLP-Dependent Amino Acid γ-Substitution Enzyme That Catalyzes C-C Bond Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:10506–10515. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c03535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee D. A. Kakule T. B. Cheng W. Chen M. Chong C. T. Y. Hai Y. Hang L. F. Hung Y.-S. Liu N. Ohashi M. Okorafor I. C. Song Y. Tang M. Zhang Z. Tang Y. Genome Mining of Alkaloidal Terpenoids from a Hybrid Terpene and Nonribosomal Peptide Biosynthetic Pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:710–714. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b13046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner J. R. Hussaini S. R. Blankenship J. D. Pal S. Branan B. M. Grossman R. B. Schardl C. L. On the sequence of bond formation in loline alkaloid biosynthesis. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:1078–1088. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z. Overbay J. Wang X. Liu X. Zhang Y. Bhardwaj M. Lemke A. Wiegmann D. Niro G. Thorson J. S. Ducho C. van Lanen S. G. Pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-dependent alkyl transfer in nucleoside antibiotic biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020;16:904–911. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0548-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borcsok E. Abeles R. H. Mechanism of action of cystathionine synthase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1982;213:695–707. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90600-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murooka Y. Kakihara K. Miwa T. Seto K. Harada T. O-alkylhomoserine synthesis catalyzed by O-acetylhomoserine sulfhydrylase in microorganisms. J. Bacteriol. 1977;130:62–73. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.1.62-73.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsson R. P.-A. Smits S. H. J. Schmitt L. Slotboom D.-J. Poolman B. A structural classification of substrate-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2606–2617. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milo R. Jorgensen P. Moran U. Weber G. Springer M. BioNumbers – the database of key numbers in molecular and cell biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D750–3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldal M. Norland S. Fagerbakke K. M. Thingstad F. Bratbak G. The elemental composition of bacteria: A signature of growth conditions? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1996;33:3–9. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(97)00007-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal G. A. L-Canavanine: a higher plant insecticidal allelochemical. Amino Acids. 2001;21:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s007260170017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan N. D. Chowdhary P. K. Haines D. C. González J. E. L-Canavanine made by Medicago sativa interferes with quorum sensing in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:8427–8436. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.24.8427-8436.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendrygal K. E. González J. E. Environmental regulation of exopolysaccharide production in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:599–606. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.3.599-606.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Tinoco C. E. Tschan F. Fuhrer T. Margot C. Sauer U. Christen M. Christen B. Co-catabolism of arginine and succinate drives symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2020;16:e9419. doi: 10.15252/msb.20199419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farssi O. Saih R. El Moukhtari A. Oubenali A. Mouradi M. Lazali M. Ghoulam C. Bouizgaren A. Berrougui H. Farissi M. Synergistic effect of Pseudomonas alkylphenolica PF9 and Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm41 on Moroccan alfalfa population grown under limited phosphorus availability. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021;28:3870–3879. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korir H. Mungai N. W. Thuita M. Hamba Y. Masso C. Co-inoculation Effect of Rhizobia and Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria on Common Bean Growth in a Low Phosphorus Soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:141. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matse D. T. Huang C.-H. Huang Y.-M. Yen M.-Y. Effects of coinoculation of Rhizobium with plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on the nitrogen fixation and nutrient uptake of Trifolium repens in low phosphorus soil. J. Plant Nutr. 2020;43:739–752. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2019.1702205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev O. Karasov T. L. Lundberg D. S. Ashkenazy H. Pramoj Na Ayutthaya P. Weigel D. Commensal Pseudomonas strains facilitate protective response against pathogens in the host plant. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022;6:383–396. doi: 10.1038/s41559-022-01673-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.