Abstract

Background

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) act as gene expression regulators and are involved in cancer progression. However, their functions have not been sufficiently investigated in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC).

Methods

The expression profiles of circRNAs in NPC cells within different metastatic potential were reanalyzed. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR and in situ hybridization were used to detect the expression level of circPVT1 in NPC cells and tissue samples. The association of expression level of circPVT1 with clinical properties of NPC patients was evaluated. Then, the effects of circPVT1 expression on NPC metastasis were investigated by in vitro and in vivo functional experiments. RNA immunoprecipitation, pull-down assay and western blotting were performed to confirm the interaction between circPVT1 and β-TrCP in NPC cells. Co-immunoprecipitation and western blotting were performed to confirm the interaction between β-TrCP and c-Myc in NPC cells.

Results

We find that circPVT1, a circular RNA, is significantly upregulated in NPC cells and tissue specimens. In vitro and in vivo experiments showed that circPVT1 promotes the invasion and metastasis of NPC cells. Mechanistically, circPVT1 inhibits proteasomal degradation of c-Myc by binding to β-TrCP, an E3 ubiquiting ligase. Stablization of c-Myc by circPVT1 alters the cytoskeleton remodeling and cell adhesion in NPC, which ultimately promotes the invasion and metastasis of NPC cells. Furthermore, c-Myc transcriptionally upregulates the expression of SRSF1, an RNA splicing factor, and recruits SRSF1 to enhance the biosynthesis of circPVT1 through coupling transcription with splicing, which forms a positive feedback for circPVT1 production.

Conclusions

Our results revealed the important role of circPVT1 in the progression of NPC through the β-TrCP/c-Myc/SRSF1 positive feedback loop, and circPVT1 may serve as a prognostic biomarker or therapeutic target in patients with NPC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12943-022-01659-w.

Keywords: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, circPVT1, c-Myc, β-TrCP, SRSF1, Metastasis

Background

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignant tumor that occurs in the nasopharynx and has a characterized geographical distribution, within highest incidence in South China and Southeast Asia [1]. As early symptoms of NPC are not obvious or specific, most patients have neck lymph node metastasis when they are diagnosed. Although radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy are effective for the treatment of early-stage NPC, lower rate of early diagnosis and prone to metastasis blunted the treatment effect [2–5]. Recurrence and metastasis are major reasons for treatment failure and patient death in NPC [6–9]. Deeper understanding of the molecular mechanism of NPC metastasis, and clearly identifying early diagnostic biomarkers and novel therapeutic targets have become urgent scientific challenge in the field.

Circular RNAs (circRNAs), a new class of non-coding RNAs, have been reported playing important roles in cancer progress [10–19]. However, their functions and potential mechanisms in the carcinogenesis and metastasis of NPC are still not fully understood. To investigate the role of circRNAs in NPC development, the expression profile of circRNAs in NPC cells was reanalyzed and a circRNA derived from PVT1 gene, named circPVT1 (circBase ID: hsa_circ_0001821), was selected for further study because of its high abundance. Our in vitro and in vivo experiments showed that circPVT1 could promote the invasion and metastasis of NPC. Further experiments demonstrated that circPVT1 inhibited ubiquitin-mediated degradation of c-Myc by binding to β-TrCP, an E3 ubiquitin ligase for c-Myc. Stablized c-Myc then modulated the expression of genes related to cell adhesion and cytoskeleton remodeling, and promoted the migration and invasion of NPC cells. In addition, the transcription factor c-Myc could upregulate and recruit SRSF1, a splicing factor, to synergistically enhance circPVT1 biosynthesis in a transcription/splicing coupling manner. Our data suggest that circPVT1 is a pivotal regulator for the metastatic process of NPC, and may function as a novel biomarker/target for the diagnosis/treatment of NPC.

Methods

Cell lines

NPC cells 5-8F and CNE2 used in this study were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a constant temperature incubator.

Clinical NPC samples

One cohort of 60 NPC and 26 non-tumor nasopharyngeal epithelial (NPE) tissues was used for RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) assay (Table S1). Another cohort of paraffin embedded sections, including 159 NPC and 29 NPE samples, was used for in situ hybridization (ISH) (Table S2). These clinical NPC samples were collected from the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University and confirmed by histopathological examination. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Central South University, and each participant provided informed consent.

In situ hybridization, fluorescence in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry

Digoxigenin- or FITC-labeled probes (BOSTER, Wuhan, China) were used for in situ hybridization (ISH) or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to detect circPVT1 expression in NPC tissues following the instructions provided by the manufacturers. Immunohistochemistry was performed using the Elivision™ plus (Mouse/Rabbit) immunohistochemistry (IHC) kit (Kit-9902, Maxim, China). Two specialized pathologists evaluated the staining sections independently. Semi-quantitative integral analysis was used to analyze the ISH and IHC. The circPVT1 probe used in the study is listed in Table S3.

Vectors, siRNA sequences, and cell transfection

To construct the overexpression vector for circPVT1, exon 2 of the PVT1 gene was amplified by PCR and cloned into the circular RNA expression vector pCirc (gift from Yong Li, Baylor College of Medicine, USA). circPVT1 siRNA was purchased from Genepharma (Shanghai, China). The overexpression vector was transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies, NY, USA) and siRNA transfection was performed using Hiperfect (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Primers used are listed in Table S3.

qRT-PCR

The Vazyme (Nanjing, China, Vazyme) reverse transcription kit was used to reverse transcribe RNA to cDNA. SYBR Green (Bimake, Shanghai, China) was used for qRT-PCR analysis, and GAPDH were used as an internal reference. The primers used in this study were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). The sequences of primers are shown in Table S3.

Would healing and transwell invasion assays

For wound healing assay, cells were grown in 6-well plates to near confluence and scratched using a 10 μl tip. Pictures were taken under the microscope at 0 h and 24 h. To analyze cell invasion ability, 20 μl of 10% Matrigel (BD Biosciences, NJ, USA) was added to Transwell chambers in serum-free medium. Transfected cells were seeded to Transwell with 20% FBS medium culture the bottom of 24-well plate. The number of cells crossing was counted from three randomly selected areas, and cell counts were tallied using the Image J software.

Lung metastatic xenograft model

Five-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were raised in an SPF-free barrier environment at the Experimental Animal Center of Central South University. For lung metastasis experiments, nude mice were randomly divided into four groups (n = 9 per group). Each nude mouse was injected via the tail vein with 1 × 106 NPC CNE2 cells transfected with the circPVT1 overexpression vector, circPVT1 siRNA, the empty vector, or scrambled siRNA. After eight weeks, nude mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Lung tissue was removed, weighed, and imaged, and the number of nodules on the surface of the lung was recorded to assess tumor metastasis. Lung tissues were then subjected to gradient dehydration, sectioned, embedded in paraffin, and stained with H&E for histological examination.

Footpad xenograft lymph node metastasis model

Five-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were raised in an SPF-free barrier environment at the Experimental Animal Center of Central South University. To establish a nude mice footpad xenograft lymph node metastasis model, CNE2 cells transfected with the empty vector and siRNA control, the circPVT1 overexpression plasmid, or circPVT1 siRNA, were injected into the footpads of mice (n = 7 per group). After 21 days later, mice were euthanized after excision of footpad tumors and inguinal lymph nodes for H&E staining and other subsequent analyses.

RNA pull-down experiment

The biotin-labeled circPVT1 probe was synthesized by Sangon Biotech, and the RNA pull-down assay was performed as previously described with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were harvested 48 h after transfection, then lysed and sonicated. The biotin-labeled circPVT1 probe (Sangon Biotech) was incubated with cell lysates at 4 °C overnight, and then incubated with Streptavidin affinity magnetic beads for another 2 h at room temperature. The supernatant was analyzed by western blotting after washing. The circPVT1 probe used is listed in Table S3.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

RIP was conducted with a Magna RIP kit (Millipore) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were harvested and lysed in the complete RIP lysis buffer and incubated with magnetic beads conjugated with specific antibodies or negative control IgG antibody on a rotator overnight at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitated RNA was purified and enriched to detect the target RNA by qRT-PCR.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS)

Mass spectrometry assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modifications. Briefly, CNE2 cells were transfected with the circPVT1 overexpression plasmid or the empty vector for 48 h. Total proteins were extracted and digested with protease. Peptides were dissolved in 0.1% formic acid (solvent A) and separated by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography system Easy-NLC 1000. Finally, peptides were subjected to NSI source followed by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) in Q Exactive™ Plus (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) coupled online to the UPLC database. The LC–MS/MS data were processed using the Proteome Discoverer 2.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The mass error was set to 10 ppm for precursor ions and 0.02 Da for fragment ions. Peptides confidence was at high, and peptides ion score was set > 20. For proteins identification, at least one unique peptide with a minimum 6 amino acid length was required. For differentially expressed proteins, the fold change was set ≥ 1.50 or ≤ 0.60 (Student's t-test, p < 0.05). The Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software was used to obtain enrichment pathways according to the above differentially expressed proteins.

Immunoprecipitation

Antibodies were mixed with 50 μL protein A/G magnetic beads (Bimake, USA) and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with rotation. Cells were lysed using the IP lysis buffer with protease inhibitor (Roche, USA) and left on ice for 2 h. Lysates were centrifuged, and supernatants were incubated with antibody-coupled beads overnight at 4 °C. Then, the antibody-bead complexes are washed 4 times with pre-chilled washing buffer. The complexes are then resuspended for western blotting. The primary antibodies used are listed in Table S4.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and then blocked with 5% BSA firstly. Then cells were incubated with specific antibodies overnight at 4 °C, washed 3–5 times with pre-chilled 0.5 M PBS and incubated with the corresponding fluorescent secondary antibody for 1 h at 37 °C. DAPI was used to stain the nucleus for 10 min and cells were photographed under a confocal microscope (Ultra-View Vox, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The primary antibodies used are listed in Table S4.

Western blotting

Total proteins were lysed using the RIPA buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) containing a protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Sciences, Mannheim, Germany), separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk with TBST for 2 h at room temperature and incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibodies (CUSBIO, Wuhan, China) for 2 h at room temperature. The proteins were then detected using ECL reagent (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The primary antibodies used are listed in Table S4.

Measurement of cellular biophysical properties

A JPK NanoWizard 4 BioScience AFM (JPK Instru-ments, Berlin, Germany) was used to optically align the probe to the cells. The probes used in this study were HYDRA6V-100NG (AppNano, CA, USA) with a nominal spring constant of 0.292 N/m. During the indentation process, the loading and retraction speeds of all experiments were maintained at ~ 2.5 μm/s to avoid viscosity effects. Measurements were made in PBS at room temperature, and the cells were plated on the bottom of the cell culture dish. After transfection of the circPVT1 overexpression vector for 48 h, NPC cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde for 45 s and 4% polymethanol solution for 30 min. Then, NPC cells were washed five times with PBS and maintained in appropriate amount of PBS for subsequent AFM scanning. The indentation depth was at least 1 mm to better simulate physiologically occurring deformations. Imaging was performed using the QI mode, and images of the AFM scan were analyzed using JPK image processing software. The force and indentation curves from each measurement were analyzed using a Hertz model to obtain the the stiffness and adhesion for each cell.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism 8 software. Student’s t-tests were used to evaluate significant differences between any two groups of data, and one-way ANOVA was used to evaluate significant differences for multiple comparisons. All data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

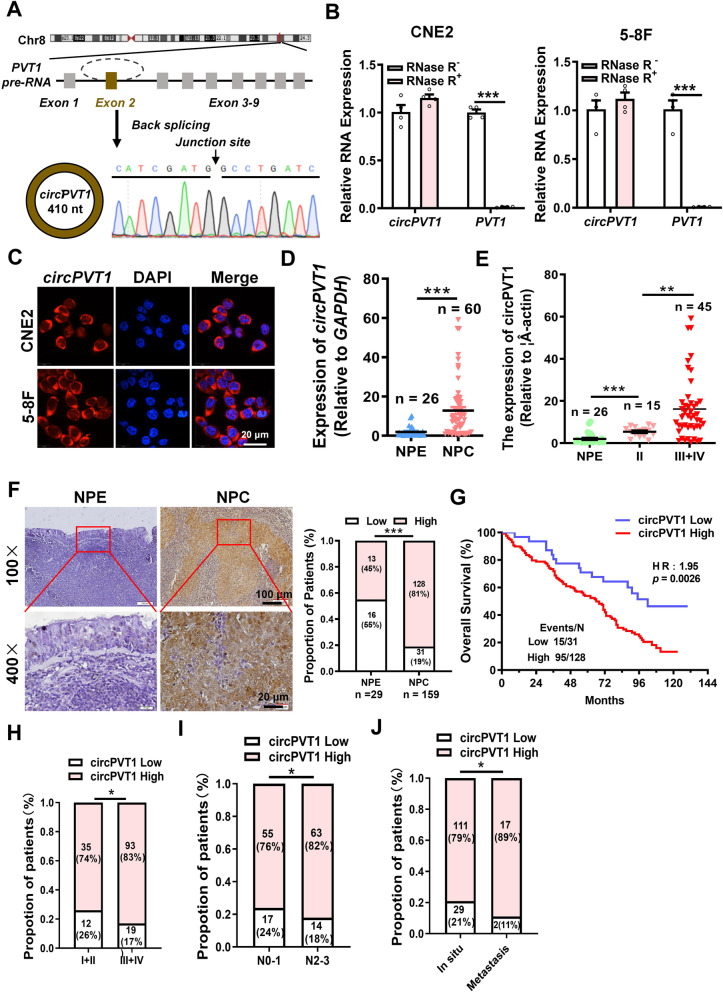

circPVT1 is highly expressed in NPC and associated with poor prognosis

To screen circRNAs that may regulate the progression of NPC, we reanalyzed the high-throughput RNA sequencing data (Accession numbers: GSE137543) of two NPC cell lines with different metastatic abilities (S18 cells with high metastasis potential and S26 cells with low metastasis potential). In total differentially expressed 20 circRNAs were found in the highly metastatic S18 cell line (Fold changes ≥ 1.5 and the RPM value ≥ 2), compared with S26. Combined with the other high-throughput RNA sequencing data (Accession numbers: PRJNA391554) in highly metastatic 5-8F cell line, circPVT1 was selected for its high abundance in both sets of data (Fig. S1A-B). qRT-PCR and Sanger sequencing confirmed that circPVT1 is backspliced by the exon 2 of PVT1, a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) gene locate on the chromosome 8q24, and the full length of circPVT1 is 410 nt (Fig. 1A). RNase R treatment revealed that circPVT1 was more resistant to degradation than lncRNA PVT1 in NPC cells (Fig. 1B). Nucleoplasmic separation assays and RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization assays revealed that circPVT1 was mainly localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. S1C, Fig. 1C). To examine the expression of circPVT1 in NPC, qRT-PCR was performed in 60 NPC tissues and 26 noncancer nasopharyngeal epithelial tissues (NPE). The results showed that circPVT1 was highly expressed in NPC samples (Fig. 1D). Moreover, the high expression of circPVT1 was closely correlated with progression of NPC (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, the high expression of circPVT1 in NPC tissues was further confirmed in 159 NPC and 29 noncancer NPE paraffin sections using ISH (Fig. 1F), and the high expression of circPVT1 was positively correlated with poor prognosis (Fig. 1G), clinical stages (Fig. 1H), N stages (Fig. 1I), and distant metastasis (Fig. 1 J) in NPC patients. These data demonstrate that circPVT1 is highly expressed in NPC and may be involved in the progression of NPC, circPVT1 may be a potential biomarker for the detection of NPC metastasis.

Fig. 1.

circPVT1 is highly expressed in NPC and associated with poor prognosis. A. Schematic representation of the circPVT1 stucture. circPVT1 is 410 nt in length and circularly spliced from exon 2 of the PVT1 gene (RefSeq: NC_000008.11) on chromosome 8q24.21. B. circPVT1 was more stable than the liner PVT1 in NPC cells after RNase R treatment. ***, p < 0.001. C. Intracellular localization of circPVT1 was examined using fluorescence in situ hybridization. Scale bar, 20 μm. D. Expression of circPVT1 was examined in NPC (n = 60) and non-tumor nasopharyngeal epithelial tissues (NPE) (n = 26) by qRT-PCR. Data were represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). ***, p < 0.001. E. The expression of circPVT1 in correlation with the clinical stages in 26 NPE and 60 NPC samples. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. F. Expression of circPVT1 was examined in NPC (n = 159) and non-tumor nasopharyngeal epithelial tissues (NPE) (n = 29) by in situ hybridization; Scale bar: 100 × , 100 μm; 400 × , 20 μm. Left: Representative images of the circPVT1 expression in NPC and NPE tissues. Right: The statistical results of the circPVT1 expression in NPC and NPE tissues. ***, p < 0.001. G. Overall survival (OS) analysis of patients with low and high circPVT1 staining using a Kaplan–Meier curve. H-I. The circPVT1 staining in correlation with the clinical stages (H) and N stages (I) of patients with NPC. *, p < 0.05. I. High circPVT1 expression was associated with distant metastasis in NPC patients. *, p < 0.05

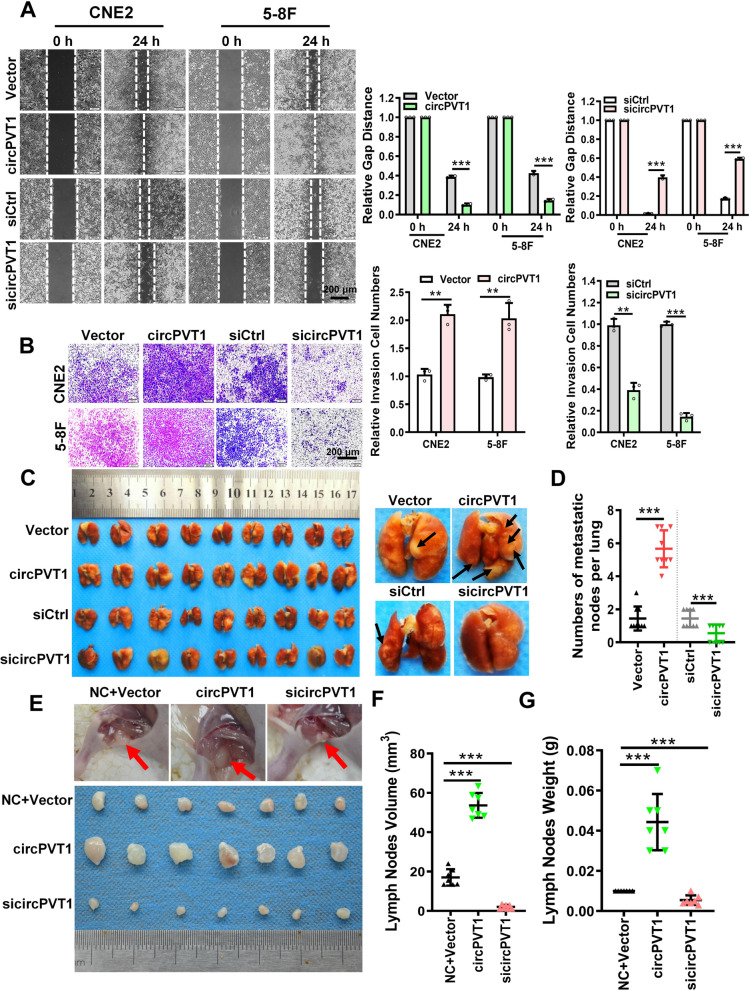

circPVT1 promotes the invasion and metastasis of NPC cells in vitro and in vivo

To explore the effect of circPVT1 on the invasion and metastasis of NPC cells, circPVT1 was specifically overexpressed or knocked down in NPC cells (Fig. S2A-B). Wound healing and Transwell assays showed that the migration and invasion ability of NPC cells was significantly enhanced after overexpression of circPVT1 and reduced after knockdown of circPVT1 (Fig. 2A-B). Cell Counting Kit-8 and colony formation assays showed that circPVT1 had little effect on the growth and proliferation of NPC cells (Fig. S2C-D). We also investigated the effect of circPVT1 on NPC cells metastasis in vivo. A lung metastatic colonization model was established through inoculating CNE2 cells transfected with the circPVT1 overexpression vector or sicircPVT1 into nude mice tail vein (n = 9 per group). The number of lung nodules of the circPVT1 overexpression group was significantly higher than that of the control group, while it was lower in the circPVT1 knockdown group (Fig. 2C-D, Fig. S2E). NPC is prone to metastasis via lymph-vessel. To better evaluate the effect of circPVT1 in promoting NPC cell metastasis in vivo, a nude mouse model of inguinal lymph node metastasis was constructed through footpad injection of CNE2 cells with overexpression or knockdown of circPVT1. The results showed that inguinal lymph nodes in the circPVT1 group were larger than the control group (Fig. 2E-G, Fig. S2F). Immunohistochemistry showed that pan-cytokeratin-positive expression in the lymph nodes of the circPVT1 group was significantly higher than that in the circPVT1 knockdown group (Fig. S2G). These results show that circPVT1 can promote the invasion and metastasis of NPC in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 2.

circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC cells in vitro and NPC metastasis in vivo. A. Wound healing assay showed that circPVT1 promoted CNE2 and 5-8F cell migration. Images were acquired at 0 and 24 h. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001. B. Transwell assay showed that circPVT1 promoted CNE2 and 5-8F cell invasion. Data were represented as mean ± SD. **, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. C. Images of visible nodules on the lung surface. CNE2 cells transfected with empty vector, circPVT1 overexpression vector, scrambled siRNA, or sicircPVT1 were injected into nude mouse tail vein (n = 9 for each group), and mice were sacrificed 8 weeks later. Arrows showed visible nodules on the lung surface. D. Quantification of lung metastatic nodules on lung surface. Data were represented as mean ± SD (n = 9 per group). ***, p < 0.001. E. Representative images of mice lymph nodes in the popliteal fossa of mice after injection with transfected CNE2 cells. F-G. Lymph nodes volumes (F) and lymph nodes weights (G) were measured for each group (n = 7 per group). Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001

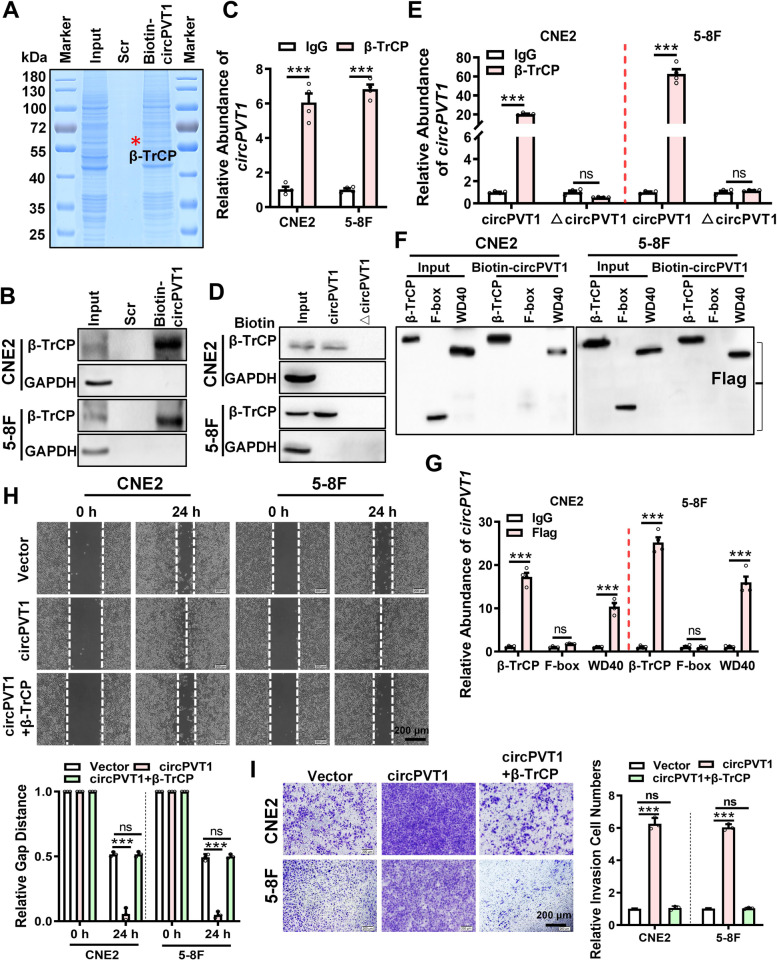

circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC cells by binding to β-TrCP

To elucidate the mechanism of circPVT1 on NPC metastasis, biotin-labeled probe of circPVT1 was used to pull-down circPVT1 and its binding proteins. The circPVT1 binding proteins were identified by LC–MS/MS (Fig. 3A, Table S5). Among these circPVT1 binding proteins, according to the protein score and peptide sequence coverage, we found that an E3 ubiquitin protein ligase β-TrCP was extremely abundant (Fig. S3A). Furthermore, the interaction between circPVT1 and β-TrCP protein was predicted, and 230–280 nt of circPVT1 was assumed to bind to β-TrCP protein by the catRAPID website (Fig. S3B) and by the molecular docking website (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/) (Fig. S3C) according to the interaction score. RNA pull-down (Fig. 3B) and RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays (Fig. 3C) confirmed the interaction between them. Then, 230–280 nt of circPVT1 was deleted and the mutant circPVT1 (△circPVT1) was constructed. RNA pull-down (Fig. 3D) and RNA immunoprecipitation (Fig. 3E) results verified that the mutant circPVT1 (△circPVT1) could not bind to β-TrCP and had no effect on the migration and invasion abilities of NPC cells compared with the wild type circPVT1 (Fig. S3D-E). These results suggest that 230–280 nt of circPVT1 is crucial for circPVT1 to interact with β-TrCP. Protein β-TrCP has two functional domains, the F-box domain and the WD40 repeat domain. To identify the binding region of β-TrCP that interacts with circPVT1, the truncated mutants, which only containing F-box domain or the WD40 repeat domain were constructed into the empty vector with Flag tag (Fig. S4A). RNA pull-down (Fig. 3F) and RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) (Fig. 3G) results indicated that the WD40 repeat domain but not the F-box domain of β-TrCP interact with circPVT1. Wound healing and transwell assays further showed that overexpression of β-TrCP could inhibit the migration and invasion of NPC cells (Fig. S4B-C) and also significantly reduced the migrative and invasive abilities of circPVT1 in NPC cells (Fig. S4D, Fig. 3H-I). These results suggest that circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC cells by binding with the WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP through its 230–280 nt fragment.

Fig. 3.

circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC cells by binding to β-TrCP. A. LC–MS/MS were performed to identify circPVT1 interacting proteins in CNE2 cells after pull-down with biotin-labeled circPVT1 probe. The unlabeled circPVT1 probe was used as control. B. Binding of circPVT1 and β-TrCP protein was analyzed in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after RNA pull-down with biotin-labeled circPVT1 probe. The biotin-labeled scrambled sequences was used as a control. C. Direct binding of β-TrCP protein to circPVT1 was evaluated in CNE2 and 5-8F cells by RNA immunoprecipitation using anti-β-TrCP antibody, followed by qRT-PCR analysis of circPVT1. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001. D. The 230–280 nt of circPVT1 was crucial for the interaction between circPVT1 and β-TrCP proteins. CNE2 and 5-8F cells were transfected with the full-length circPVT1 (circPVT1) or the 230–280 nt deleted mutant (△circPVT1). RNA pull-down assays were performed using biotin-labeled circPVT1 probe, followed by western blotting using anti-β-TrCP antibody. E. β-TrCP protein directly binds to the 230–280 nt of circPVT1 in CNE2 and 5-8F cells. Cells were were transfected with the full-length circPVT1 or the deletion mutant (△circPVT1). RNA immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-β-TrCP antibody, followed by qRT-PCR of circPVT1. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. F. The binding between circPVT1 and the WD40 domain of β-TrCP protein was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after transfected with Flag-tagged full-length β-TrCP or truncated mutants (F-box or WD40). RNA pull-down assays were performed using biotin-labeled circPVT1 probe, followed by western blotting using anti-Flag antibody. G. The binding between circPVT1 and the WD40 domain of β-TrCP protein was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells. After transfected withFlag-tagged full-length β-TrCP or truncated mutants (F-box or WD40), RNA was immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag antibody. IgG was used as a control. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. H. Wound healing assay showed that overexpression of β-TrCP reverses the migrative ability of cicPVT1 in NPC cells. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. I. Transwell assay showed that overexpression of β-TrCP reverses the invasive ability of cicPVT1 in NPC cells. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant

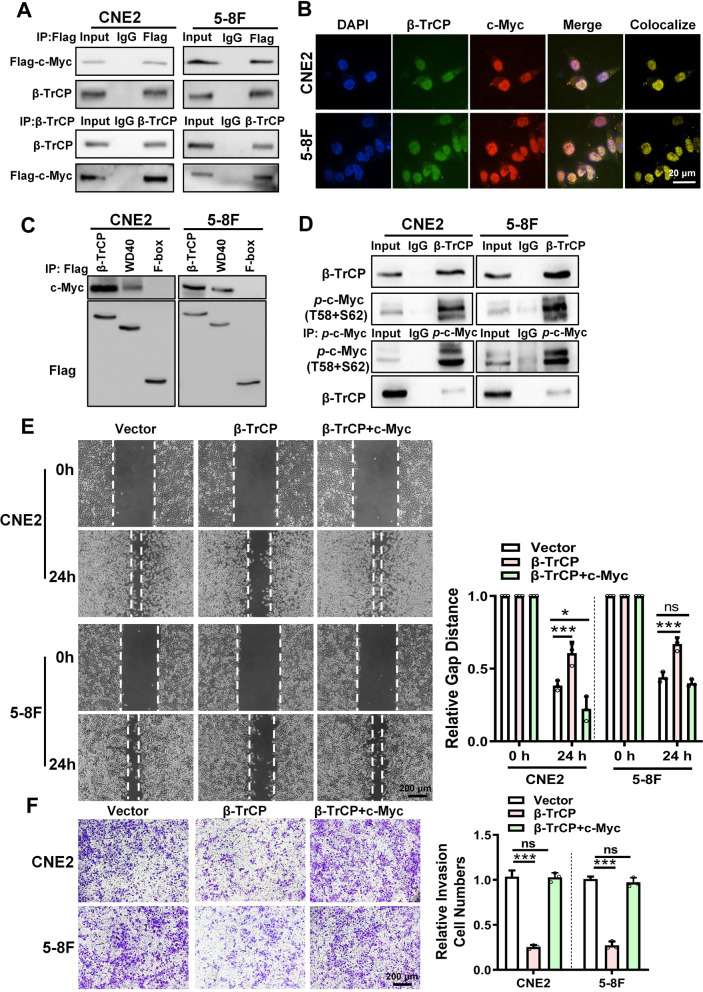

circPVT1 blocks β-TrCP binding to c-Myc and inhibits the ubiquitination of c-Myc

To test whether circPVT1 interferes with the E3 ubiquitin ligase function of β-TrCP to regulate its target proteins, the β-TrCP expression level was assessed in NPC cells after overexpressing or knockdown of circPVT1. The results showed that circPVT1 did not affect the expression of β-TrCP (Fig. S5A). We hypothesized that circPVT1 might regulate its downstream proteins expression through influencing the binding of β-TrCP to its substrates. To identify the substrates of β-TrCP in NPC cells, co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) was performed using β-TrCP anibody, followed by the mass spectrometry. A total of 260 proteins were identified and c-Myc exhibited high affinity towards β-TrCP (Fig. S5B, Table S6). Co-IP and immunofluorescence experiments confirmed the interaction between β-TrCP and c-Myc proteins (Fig. 4A-B). The binding domain of c-Myc and β-TrCP were predicted by Molecular Docking (Fig. S5C), which showed that c-Myc might also bind to the WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP, which is the same domain that circPVT1 binds to. Co-IP results confirmed the binding between the WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP and c-Myc (Fig. 4C). c-Myc is usually phosphorylated at threonine 58 and serine 62 sites, which were recognized by E3 ubiquitin ligases. Further Co-IP experiments showed that β-TrCP prefered to interacting with the phosphorylated c-Myc protein (Fig. 4D). Overexpression of β-TrCP enhanced the ubiquitination of c-Myc and reduced the c-Myc protein level in NPC cells (Fig. S5D-E). We further co-transfected β-TrCP and c-Myc expressing vectors into the NPC cells. Wound-healing and Transwell assays showed that overexpression of β-TrCP inhibited the mobility and invasiveness of NPC cells, whereas restoration of c-Myc rescued migratory and invasive abilities of NPC cells upon overexpression of β-TrCP. These results indicated that c-Myc is the critical factor for NPC metastasis downstream of circPVT1/β-TrCP interaction.

Fig. 4.

c-Myc is ubiquitinated substrate of β-TrCP. A. The interaction between β-TrCP and c-Myc proteins was examined using immunoprecipitation expriments in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after transfected with Flag tagged c-Myc. B. Immunofluorescence experiments showed that β-TrCP and c-Myc were co-localized in CNE2 and 5-8F cells. blue: DAPI-stained nucleus; green: anti-β-TrCP; red: anti-c-Myc; yellow: co-localization of β-TrCP and c-Myc. The merged image represented the overlap of DAPI, β-TrCP, and c-Myc. Scale bar, 20 μm. C. The interaction between c-Myc and the WD40 domain of β-TrCP was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after transfected with Flag-tagged full-length β-TrCP or truncated fragments (F-box or WD40 domain) by immunoprecipitation using anti-Flag antibody. D. The interaction between β-TrCP and phosphorylated c-Myc proteins was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells by immunoprecipitation with anti-β-TrCP or anti-phosphorylated (T58 + S62) c-Myc antibodies. E. Wound healing assay showed that overexpression of c-Myc reverses the migrative ability of β-TrCP in NPC cells. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. F. Transwell assay showed that overexpression of c-Myc reverses the invasive ability of β-TrCP in NPC cells. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant

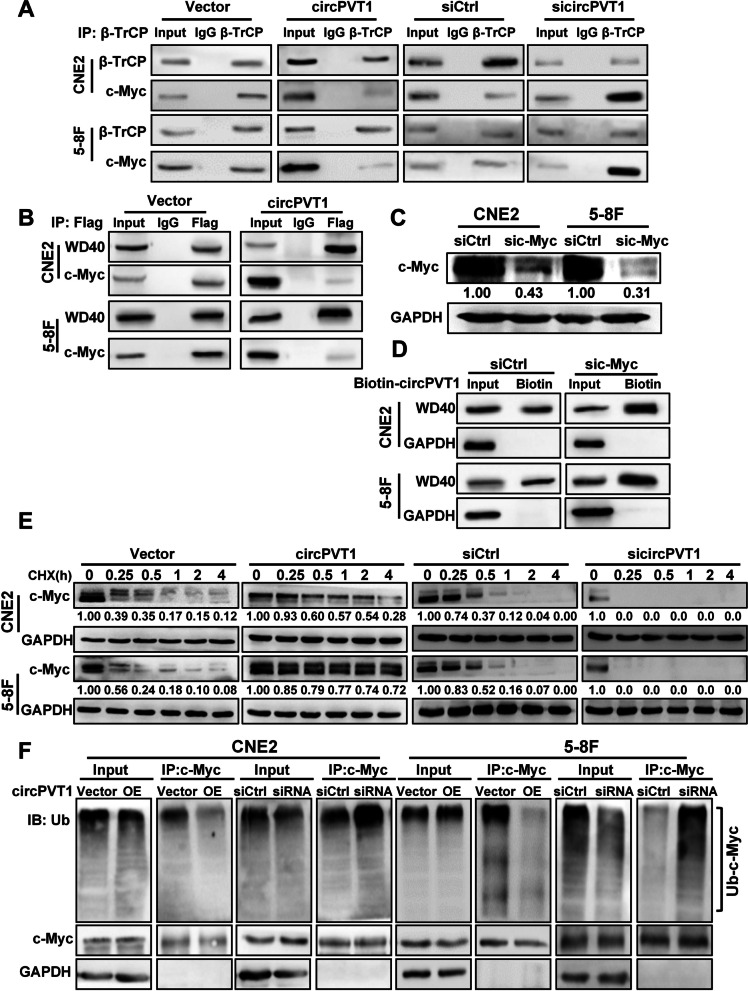

The above results also suggested that circPVT1 might preoccupy the WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP which was required for c-Myc binding in NPC cells, resulting in decreased c-Myc ubiquitination by β-TrCP. To test if circPVT1 regulated the ubiquitination of c-Myc by β-TrCP, Co-IP was performed and the results showed that overexpression of circPVT1 reduced the interaction between β-TrCP and c-Myc, whereas knockdown of circPVT1 enhanced it in NPC cells (Fig. 5A). In addition, overexpression of circPVT1 decreased the binding of c-Myc to the WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, RNA pulldown results showed that the binding of circPVT1 to the WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP increased after c-Myc knockdown (Fig. 5C-D). These results suggested that circPVT1 and c-Myc competitively bound to the WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP. When NPC cells were treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) (50 μg/mL), the stability of c-Myc protein increased after overexpression of circPVT1 and decreased after knockdown of circPVT1 in NPC cells (Fig. 5E). Overexpression of circPVT1 also significantly inhibited the ubiquitination of c-Myc protein, whilst knockdown of circPVT1 had the opposite effect (Fig. 5F). The above data demonstrated that circPVT1 stabilizd c-Myc protein in NPC cells through competitively binding with β-TrCP to block the interaction between β-TrCP and c-Myc, therefore preventing β-TrCP-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of c-Myc.

Fig. 5.

circPVT1 blocks the binding of β-TrCP to c-Myc and inhibits the ubiquitination of c-Myc. A. The interaction between β-TrCP and c-Myc proteins was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression or knockdown of circPVT1 by immunoprecipitation using anti-β-TrCP antibody. B. The interaction between WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP and c-Myc proteins was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression of circPVT1 by immunoprecipitation using anti-Flag antibody. C. The expression of c-Myc proteins was examined by western blotting in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after transfected with c-Myc siRNA. D. Binding of circPVT1 and WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP protein was detected in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after knockdown of c-Myc by RNA pull-down assays with biotin-labeled circPVT1 probe. E. Degradation of c-Myc was detected in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression or knockdown of circPVT1 and treatment with 50 μg/mL cycloheximide (CHX). F. The ubiquitination level of c-Myc protein was determined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression or knockdown of circPVT1, immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Myc antibody, and followed by western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibody

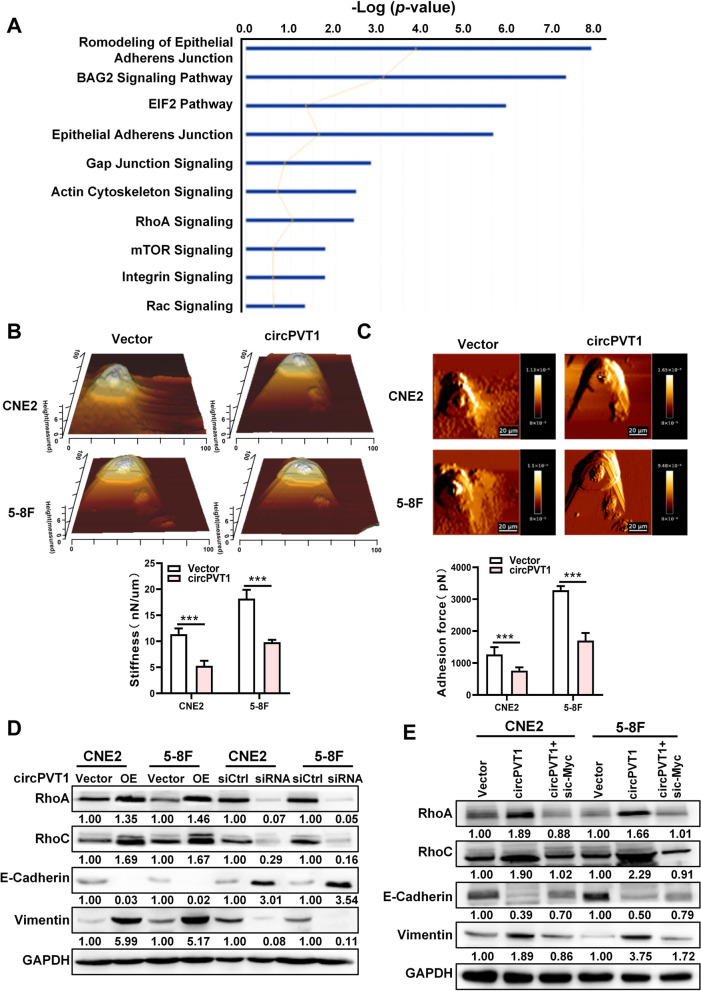

circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC cells by regulating cell adhesion and cytoskeleton remodeling

To explore downstream genes which were regulated by the circPVT1/β-TrCP/c-Myc axis, the proteome profile of NPC cells after overexpression circPVT1 was examined by mass spectrometry. A total of 231 significantly differentially expressed proteins were identified (Table S7). Biological functions of these proteins were analyzed by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA), the result showed that sevral signaling pathways related to cell adhesion, cell junction and cytoskeleton were enriched. (Fig. 6A). We performed upstream factor analysis of differential proteins obtained by whole-proteome mass spectrometry data, interestingly, the results showed that a large number of differential proteins were regulated by c-Myc (Fig. S6). We then assessed the stiffness and adhesion of NPC cells after overexpresion of circPVT1 by Atomic Force Microscope (AFM). The data showed that the stiffness and adhesion of NPC cells was decreased when circPVT1 was overexpressed in NPC cells (Fig. 6B-C). In addition, several key molecules relevant to cell adhesion junctions and cytoskeleton remodeling pathways such as RhoA, RhoC, E-cadherin, and Vimentin were also examined in NPC cells after overexpression or knockdown of circPVT1, the results showed that circPVT1 could induce the expression of RhoA, RhoC, and Vimentin, whereas reduce E-cadherin expression (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, knockdown of c-Myc reversed circPVT1 induced up-regulation of RhoA, RhoC, and Vimentin, as well as circPVT1 reduced E-cadherin expression (Fig. 6E). These results suggest that circPVT1 regulate cell adhesion junctions and cytoskeleton remodeling through the circPVT1/β-TrCP/c-Myc axis.

Fig. 6.

circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC cells by regulating cell adhesion and cytoskeleton remodeling. A. Pathways enriched by the 231 potentially regulated proteins by circPVT1 from LC–MS/MS data using the gene set enrichment analysis of the Ingenuity Pathway. B. The stiffness was measured in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpresion of circPVT1. Top: The representative AFM deflection images; bottom: the statistical analysis of stiffness. ***, p < 0.001. C. The adhesion was measured in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpresion of circPVT1. Top: The representative AFM deflection images; bottom: the statistical analysis of adhesion. ***, p < 0.001. D. The expression of RhoA, RhoC, E-cadherin, and vimentin proteins was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression or knockdown of circPVT1 by western blotting. E. The expression of RhoA, RhoC, E-cadherin and vimentin proteins was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after co-transfected with the c-Myc siRNA and circPVT1 overexpression vector by western blotting

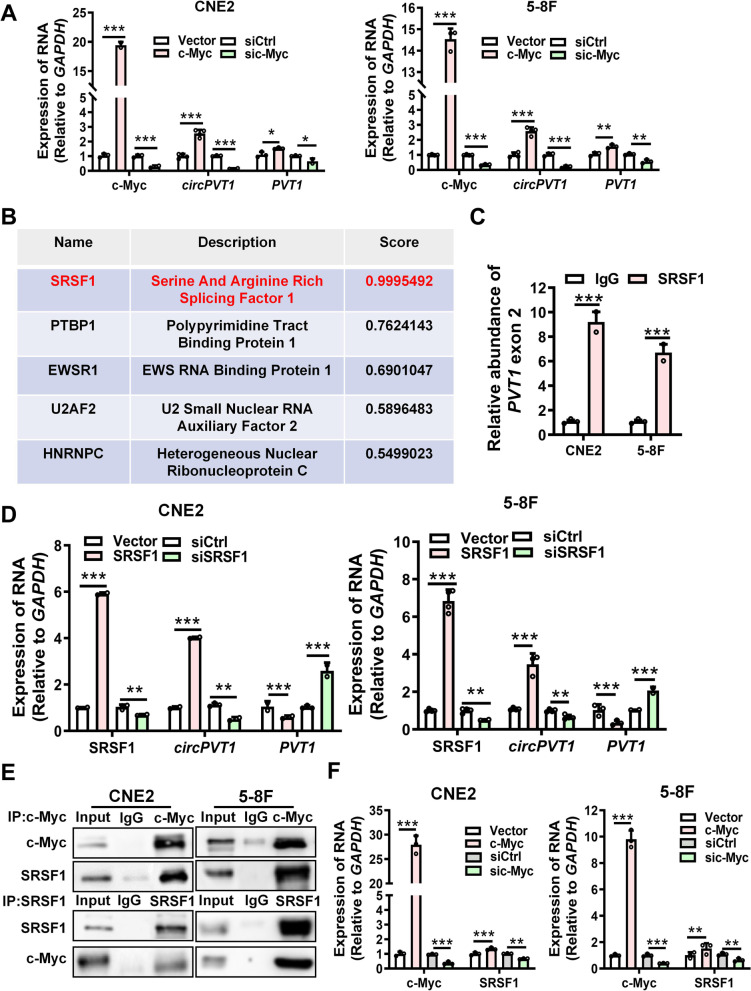

c-Myc promotes circPVT1 biosynthesis through upregulating and recruiting SRSF1

The expression of circPVT1 in NPC cells was also examined after overexpression or knockdown of c-Myc. The result of qRT-PCR showed that both circPVT1 and linear PVT1 were upregulated by c-Myc, indicating that c-Myc could promote the production of PVT1 precursor RNA at the transcriptional level (Fig. 7A). We analyzed the potential promoter region of PVT1 using bioinformatics tools. Three c-Myc potential binding sites were found in the PVT1 promoter region. Luciferase-reporter assay and ChIP-qPCR assays demonstrated that c-Myc binds to the PVT1 promoter region from -871 bp to -528 bp to promote the transcription of PVT1 (Fig. S7A-B). CircRNAs are product of RNA alternative splicing, and splicing factors are involved in the biogenesis of circRNAs. Bioinformatics analysis using the RBPsuite (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/RBPsuite/) predicted that there were several splicing factor binding sites on exon 2 of PVT1. Among these splicing factors, SRSF1 displayed the highest score (Fig. 7B). RIP experiments confirmed that SRSF1 could indeed bind to exon 2 of PVT1 (Fig. 7C). The expression of circPVT1 was elevated following SRSF1 overexpression, while the level of PVT1 was reduced. In contrary, knockdown of SRSF1 resulted in reduction of circPVT1 level but elevation of PVT1 level in NPC cells (Fig. 7D). Thus, our data suggested that SRSF1 binds to the exon 2 of PVT1 and facilitates the biogenesis of circPVT1 in NPC cells. Interestingly, Co-IP experiments revealed an unexpected interaction between c-Myc and SRSF1 (Fig. 7E). Moreover, c-Myc as a transcription factor could also promote the expression of SRSF1 (Fig. 7F, Fig. S7C-D). Finally, we performed RNA pull-down assay with fresh NPC samples. The results verified that circPVT1 could bind to β-TrCP protein extracted from fresh NPC samples. Immunohistochemical results showed that the intensity of circPVT1 was positively correlated with levels of c-Myc and SRSF1 in NPC tissues (Fig. S7E-F, Tables S8-S9). These results suggest that c-Myc not only acts as a transcription factor to promote gene transcription, but also enhances splicing of pre-RNA of PVT1 and thus facilitates the biosynthesis of circPVT1 by coupling transcription to splicing.

Fig. 7.

c-Myc promotes circPVT1 generation by recruiting SRSF1 to couple transcription to splicing. A. The expression of circPVT1 and PVT1 in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression or knockdown of c-Myc was examined using qRT-PCR. Data were represented as mean ± SD; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. B. The top 5 splicing factors potentially binding to the exon 2 of PVT1 were listed following analyzed online (RBPsuite: http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/RBPsuite/). The score for SRSF1 is highest (score = 0.9995492). C. The interaction between SRSF1 protein and exon 2 of PVT1 was evaluated in CNE2 and 5-8F cells by RNA immunoprecipitation using anti-SRSF1 antibody, followed by qRT-PCR analysis of the PVT exon 2. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001. D. The expresion of circPVT1 and PVT1 in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression or knockdown of SRSF1 was examined using RT-PCR. Data were represented as mean ± SD; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. E. The interaction between SRSF1 and c-Myc proteins was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells using immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Myc antibody, followed by western blotting using anti-SRSF1 antibody. F. The expression of SRSF1 in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression or knockdown of c-Myc was examined using qRT-PCR. Data were represented as mean ± SD; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001

Discussion

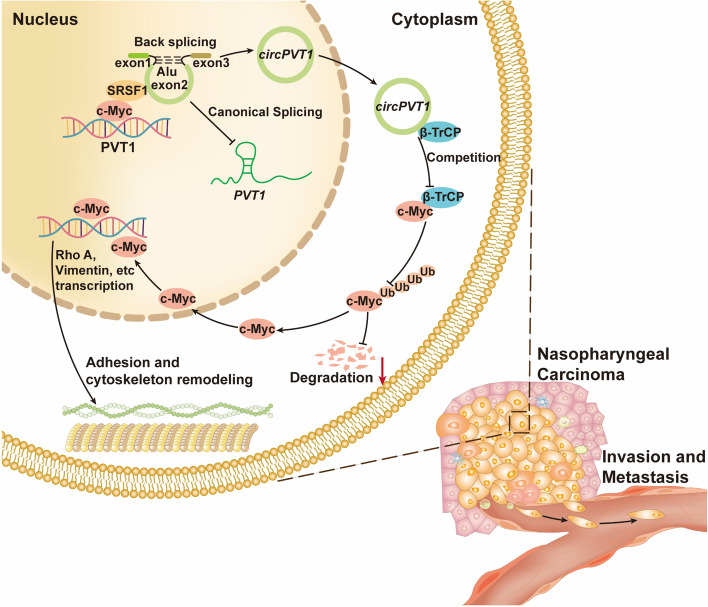

In this study, we identified a circRNA circPVT1 which was highly expressed in NPC cells and promoted NPC migration and invasion. Mechanistically, circPVT1 interacted with β-TrCP to prevent β-TrCP-induced c-Myc ubiquitination and degradation, thus boosted the migration and invasion of NPC cells. Importantly, c-Myc not only promoted PVT1 gene transcription through binding to the promoter region of PVT1, but also coordinated with the splicing factor SRSF1 to facilitate circPVT1 biogenesis. These molecules form a positive feedback loop that enhances NPC migration and invasion (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram of the molecular mechanism of circPVT1 promoted NPC metastasis. Circular RNA circPVT1 interacts with β-TrCP to prevent β-TrCP-induced c-Myc ubiquitination and degradation, which results in enhanced migration and invasion of NPC cells. Oncoprotein c-Myc promotes circPVT1 transcription through binding to the promoter region of PVT1 gene, and recruits the splicing factor SRSF1 to facilitate circPVT1 splicing, which forms a positive feedback loop that promotes the migration and invasion of NPC cells

Amplification of chromosome 8q24, which circPVT1 and lncRNA PVT1 locate on, is frequently observed in a variety of cancers including NPC [20–24]. In this study, we focused on the circRNA circPVT1 which was derived from exon 2 of the PVT1 gene and was highly expressed in NPC. The role of circPVT1 in cancer was first reported in gastric cancer. Huang et al. found that circPVT1 expression was elevated in gastric cancer and boosted the progression of gastric cancer [25]. Usually, circPVT1 acts as a miRNA "sponge" to increase the expression of miRNA targeted mRNA at the post-transcriptional level to stimulate cancer progression [26–28]. In this work, we discovered that circPVT1 could prevent β-TrCP-induced c-Myc ubiquitination and degradation through directly binding to β-TrCP protein, which ultimately promoted NPC cell migration and invasion.

As a key member ofthe F-box class of proteins, numerous studies have demonstrated that β-TrCP specifically recognizes and ubiquitinates IκB, β-catenin, and Emi1 proteins to regulate a variety of processes during tumor development [29, 30]. Here, we revealed that β-TrCP could bind and promote the degradation of c-Myc through ubiquitination. Interestingly, circPVT1 competitively occupied the c-Myc-binding domain on β-TrCP to prevent β-TrCP-induced c-Myc ubiquitination and degradation, thus enhancing NPC cell migration and invasion. CircRNAs function as signaling pathway regulators in gene expression and other important cellular processes [31–36]. For example, circRNAs may act as scaffolds or decoys of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) to form nuclear or cytoplasmic complexes [39–41]. Yang et al. found that circFoxo3 in mice functions as a scaffold by binding to the cell-cycle proteins cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (or p21). The formation of a circFoxo3–p21–CDK2 ternary complex results in inhibition of CDK2 activity [37]. As a scaffold, circFoxo3 also facilitates the degradation of mutant p53 and at the same time inhibits Foxo3 degradation by modulating double-minute 2 (MDM2)-mediated ubiquitination in murine cells [38]. Shan et al. found that circBoule RNAs interacts with conserved HSPs (heat shock proteins) and protects against stress-induced fertility decline [39]. Cai et al. found that circPABPC1 negatively regulates adhesion and migration in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by directly binding to and down-regulating ITGB1 [40]. β-TrCP is a non-classical RNA binding protein, our results showed that circPVT1 binds to β-TrCP and inhibits β-TrCP-mediated c-Myc protein degradation. Our study established an important theoretical basis for targeting circRNAs as therapeutic agents for c-Myc modulation, which is expected to fulfill the unmet clinical urgent needs.

Unexpectedly, we found that c-Myc could not only act as a transcription factor to drive gene transcription, but also bing in the splicing factor SRSF1 and facilitate transcriptional splicing of PVT1 into circPVT1, but not PVT1. Among a few studies on the generation of circRNA [41–47], Meng et al. found that transcription factor Twist1 promotes Cul2 transcription and up-regulates the expression of Cul2 circRNA through binding to Cul2 promoter [48]. Conn et al. found that the generation of circRNA was regulated by splicing factor Quaking (QKI) [49]. Wang et al. found that EIF4A3 could bind to MMP9 mRNA transcript to promote circMMP9 cyclization and enhance circMMP9 expression in glioblastoma [50]. Our work revealed a novel mechanism for upregulation of circPVT1 in NPC cells by coupling transcription with splicing event through synergetic corporation between c-Myc and SRSF1.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that circPVT1 was positively co-regulated by c-Myc and SRSF1 in NPC cells, and on the other hand circPVT1 inhibited the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of c-Myc by binding to β-TrCP, which blocked the interaction between the ubiquitin E3 ligase β-TrCP and its target c-Myc. In turn, this led to cytoskeleton remodeling and cell adhesion modulation, and ultimately promoted NPC cell migration and invasion. Our work provided new insights into the mechanism of NPC progression and potential targets for the treatment of NPC patients.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1. Clinicopathological data of 60 NPC and 26 NPE tissues measured by qRT-PCR.

Additional file 2: Supplemental Table 2. Clinicopathological data of 159 paraffin-embedded NPC tissues and 29 non-neoplastic nasopharyngeal epithelialtissues for in situhybridization.

Additional file 3: Supplemental Table 3. Probes for fluorescence in situ hybridization and RNA pulldown, siRNAs, primers for qRT-PCR and vector construction.

Additional file 4: Supplemental Table 4. List of antibodies for immunohistochemistry, western blotting, immunofluorescence, and RNA pull-down experiments.

Additional file 5: Supplemental Table 5. The potential circPVT1-interacting proteins in CNE2 cells identified by LC-MS/MS spectrometry after pull-down with the biontin-labeled circPVT1 probe.

Additional file 6: Supplemental Table 6. The potential β-TrCP-interacting proteins in CNE2 cells identified by LC-MS/MS spectrometry after pull-down with β-TrCP antibody.

Additional file 7: Supplemental Table 7. Proteomic analysis of circPVT1-regulated proteins in CNE2 cells after transfected with the circPVT1overexpression or empty vectors, followed by LC-MS/MS spectrometry.

Additional file 8: Supplemental Table 8. Clinicopathological data of 3 NPC tissues measured by RNA pull-down.

Additional file 9: Supplemental Table 9. Clinicopathologicaldata of 30 paraffin-embedded NPC tissues for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (ISH).

Additional file 10: Figure S1. A. Thedifferentially expressed circRNAs between the high metastasis NPC cell line S18 and the low metastasis NPC cell line S26 (GSE137543, the RPM value ≥ 2and Fold changes ≥ 1.5). Circular RNA circPVT1 is highly expressed in NPC cell line S18. B. The Venn diagram of data sets GSE137543 and PRJNA391554. Circular RNA circPVT1 was identified for its high abundance in both sets of data.C. circPVT1 is mainly localized in the cytoplasm as identified by nucleoplasmic separation experiments. U6 was used as a nuclear marker and GAPDH was used as a cytoplasmic marker.

Additional file 11: Figure S2. circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC in vitroand metastasis of NPCin vivo. A-B. The expression of circPVT1 were measured in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after transfection with the circPVT1 overexpression vector or circPVT1 siRNA. PVT1 expression was not affected in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpresion or knockdown of circPVT. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant. C-D. Cell Counting Kit-8 and colony formation assays showed that circPVT1 had no effect on the growth and proliferation of NPC cells. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ns, not significant. E. H&E staining of lung metastatic tumor foci and representative images of circPVT1 expression as assessed by in situ hybridization (200×, scale bar, 50 μm). F. Images of footpad tumor formation in nude mice on day 21. Mice were injected with 1×106 CNE2 cells after overexpression or knockdown of circPVT1.G. Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for pan-cytokeratin in lymphatic tissues of mice. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Additional file 12: Figure S3. circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC cells through binding to β-TrCP. A. The secondary ion flow diagram of β-TrCP identified by mass spectrometry according to the peptide sequence (DFITALPAR) of β -TrCP.B. Schematic diagram of binding sites betweent circPVT1 and β-TrCP using the catRAPID website.The 230-280 nt of circPVT1 was predicted to bind to β-TrCP protein with high interaction score.C. The secondary structure of circPVT1 changed when 230-280 nt of circPVT1 was deleted (△circPVT1).D. Wound healing assays showed that the wild type circPVT1 but not the mutant (△circPVT1) reduced the migration abilities of CNE2 and 5-8F cells after transfected with the full-length circPVT1 or the mutant (230-280 nt deleted, △circPVT1). Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. E. Transwell invasion assays showed that the wild type circPVT1 but not mutant of circPVT1 (△circPVT1) reduced the migration abilities of CNE2 and 5-8F cells wereafter transfected with the full-length circPVT1 or the mutant (230-280 nt deleted, △circPVT1). Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant.

Additional file 13: Figure S4. The WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP interacts with circPVT1. A. The functional domain of the of β-TrCP proteins are illustrated (top), including the F-box domain and the WD40 domain. The expressing plasmids for full-length β-TrCP or truncated fragments (F-box and WD40) were constructed and confirmed using anti-Flag antibody. B. Wound healing assay showed that overexpression of β-TrCP inhibited NPC cells migration. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. C. Transwell invasion assay showed that overexpression of β-TrCP inhibited NPC cells invasion. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant.

Additional file 14: Figure S5. c-Myc is ubiquitinated substrate of β-TrCP. A. The expression of β-TrCP was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression or knockdown of circPVT1 using western blotting.B. The β-TrCP binding proteins were identified in CNE2 cells by immunoprecipitation followed by LC-MS/MS.C. The interaction of c-Myc and β-TrCP was predicted by Molecular Docking (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/). The blue part is the WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP.D. The expression of c-Myc was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression of β-TrCP using western blotting.E. The ubiquitination level of c-Myc protein was determined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression of β-TrCP and immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Myc antibody, followed by western blotting with an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

Additional file 15: Figure S6. circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC cells by regulating cell adhesion andcytoskeleton remodeling. The 231 differentially expressed proteins regulated by c-Myc from LC-MS/MS data using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software.

Additional file 16: Figure S7. c-Myc promotes circPVT1 generation by recruiting SRSF1 to couple transcription to splicing. A. The luciferase reporter gene activity of the PVT1 promoter was analyzed in NPC cells after overexpression of c-Myc. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001. B. The binding of transcription factor c-Myc to the PVT1 promoter detected by ChIP assay. Three sites on the PVT1 promoter were identified as potential c-Myc binding sites (site 1, site 2 and site 3) using the Jasper and PROMO software. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. C. The luciferase reporter gene activity of the SRSF1 promoter was analyzed in NPC cells after overexpression of c-Myc. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001. D. The binding of transcription factor c-Myc to the PVT1 promoter detected by ChIP assay. Two sites on the PVT1 promoter were selected as the c-Myc binding sites (site 1 and site 2) using the Jasper and PROMO software. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. E. Binding of circPVT1 to β-TrCP protein was analyzed in NPC tissues after pulling-down with biotin-labeled circPVT1 probe. The biotin-labeled scrambled sequences was used as a control.F. Representative images showing the correlation between circPVT1 and the expression of c-Myc and SRSF1 in NPC tissues (top). Quantification of the correlation between circPVT1 and the expression of c-Myc and SRSF1 in NPC tissues (bottom). Magnification: 200×, Scale bar = 50 μm, 400×, Scale bar = 20 μm.

Abbreviations

- NPC

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- circRNA

Circular RNAs

- PVT1

Plasmacytoma variant translocation 1

- β-TrCP

Beta-transducin repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase

- LC–MS/MS

Liquid Chromatography-tandem Mass Spectrometry

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- RhoA

Ras homolog family member A

- RhoC

Ras homolog family member C

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- SRSF1

Serine and arginine rich splicing factor 1

Authors’ contributions

Bo Xiang conceived and designed the project. Yongzhen Mo completed the majority of experiments and wrote the manuscript. Yumin Wang, Yian Wang, Xiangying Deng, Chunmei Fan performed some of the experiments. Shuai Zhang, Shanshan Zhang, Zhaojian Gong, Lei Shi, Qianjin Liao, Weihong Jiang collected tissue samples. Can Guo, Yong Li, Guiyuan Li, Zhaoyang Zeng, Wei Xiong revised the manuscript. Bo Xiang is responsible for research supervision and funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U20A20367, 82073135, 82072374, 82002239, 82272631, 81972776, and 81803025), the Overseas Expertise Introduction Project for Discipline Innovation (111 Project, No. 111–2-12), the Hunan Provincial Key Research and Development Program (2022SK2026), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2020JJ4766, 2020JJ4125 and 2019JJ50872), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M693553).

Availability of data and materials

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Central South University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chen Y, Chan A, Le Q, Blanchard P, Sun Y, Ma J. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):64–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30956-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang X, Deng X, Wang J, Mo Y, Shi L, Wei F, et al. BPIFB1 inhibits vasculogenic mimicry via downregulation of GLUT1-mediated H3K27 acetylation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncogene. 2022;41(2):233–245. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-02079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Y, Wang D, Wei F, Xiong F, Zhang S, Gong Z, et al. EBV-miR-BART12 accelerates migration and invasion in EBV-associated cancer cells by targeting tubulin polymerization-promoting protein 1. FASEB J. 2020;34(12):16205–16223. doi: 10.1096/fj.202001508R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang T, Yang L, Cao Y, Wang M, Zhang S, Gong Z, et al. LncRNA AATBC regulates pinin to promote metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Oncol. 2020;14(9):2251–2270. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan C, Tu C, Qi P, Guo C, Xiang B, Zhou M, et al. GPC6 Promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cancer. 2019;10(17):3926–3932. doi: 10.7150/jca.31345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan C, Tang Y, Wang J, Wang Y, Xiong F, Zhang S, et al. Long non-coding RNA LOC284454 promotes migration and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma via modulating the Rho/Rac signaling pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2019;40(2):380–391. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgy143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mo Y, Wang Y, Xiong F, Ge X, Li Z, Li X, et al. Proteomic analysis of the molecular mechanism of lovastatin inhibiting the growth of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. J Cancer. 2019;10(10):2342–2349. doi: 10.7150/jca.30454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D, Zeng Z, Zhang S, Xiong F, He B, Wu Y, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded miR-BART6-3p inhibits cancer cell proliferation through the LOC553103-STMN1 axis. FASEB J. 2020;34(6):8012–8027. doi: 10.1096/fj.202000039RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei F, Wu Y, Tang L, Xiong F, Guo C, Li X, et al. Trend analysis of cancer incidence and mortality in China. Sci China Life Sci. 2017;60(11):1271–1275. doi: 10.1007/s11427-017-9172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Mo Y, Gong Z, Yang X, Yang M, Zhang S, et al. Circular RNAs in human cancer. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0598-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan C, Qu H, Xiong F, Tang Y, Tang T, Zhang L, et al. CircARHGAP12 promotes nasopharyngeal carcinoma migration and invasion via ezrin-mediated cytoskeletal remodeling. Cancer Lett. 2021;496:41–56. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou R, Wu Y, Wang W, Su W, Liu Y, Wang Y, et al. Circular RNAs (circRNAs) in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;425:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhong Y, Du Y, Yang X, Mo Y, Fan C, Xiong F, et al. Circular RNAs function as ceRNAs to regulate and control human cancer progression. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0827-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao M, Wang Y, Tan F, Liu L, Hou X, Fan C, et al. Circular RNA circCCNB1 inhibits the migration and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma through binding and stabilizing TJP1 mRNA. Sci China Life Sci. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11427-021-2089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang L, Xiong W, Zhang L, Wang D, Wang Y, Wu Y, et al. circSETD3 regulates MAPRE1 through miR-615-5p and miR-1538 sponges to promote migration and invasion in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncogene. 2021;40(2):307–321. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Mo Y, Peng M, Zhang S, Gong Z, Yan Q, et al. The influence of circular RNAs on autophagy and disease progression. Autophagy. 2022;18(2):240–253. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2021.1917131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qu H, Chen M, Ge J, Zhang X, He S, Xiong F, et al. A fluorescence strategy for circRNA quantification in tumor cells based on T7 nuclease-assisted cycling enzymatic amplification. Anal Chim Acta. 2022;1189:339210. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2021.339210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ge J, Wang J , Xiong F, Jiang X, Zhu K, Wang Y, et al. Epstein-barr virus-encoded circular RNA CircBART2.2 promotes immune escape of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by regulating PD-L1. Cancer Res. 2021;81(19):5074–88. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mo Y, Wang Y, Zhang S, Xiong F, Yan Q, Jiang X, et al. Circular RNA circRNF13 inhibits proliferation and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma via SUMO2. Mol Cancer. 2021;20(1):112. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01409-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang W, Zhou R, Wu Y, Liu Y, Su W, Xiong W, et al. PVT1 Promotes cancer progression via MicroRNAs. Front Oncol. 2019;9:609. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He Y, Jing Y, Wei F, Tang Y, Yang L, Luo J, et al. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 predicts poor prognosis and induces radioresistance by regulating DNA repair and cell apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(2):235. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0265-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou C, Yi C, Yi Y, Qin W, Yan Y, Dong X, et al. LncRNA PVT1 promotes gemcitabine resistance of pancreatic cancer via activating Wnt/beta-catenin and autophagy pathway through modulating the miR-619-5p/Pygo2 and miR-619-5p/ATG14 axes. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01237-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin K, Wang S, Zhang Y, Xia M, Mo Y, Li X, et al. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 interacts with MYC and its downstream molecules to synergistically promote tumorigenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76(21):4275–4289. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03222-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tu C, Zeng Z, Qi P, Li X, Guo C, Xiong F, et al. Identification of genomic alterations in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma-derived Epstein-Barr virus by whole-genome sequencing. Carcinogenesis. 2018;39(12):1517–1528. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgy108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J, Li Y, Zheng Q, Bao C, He J, Chen B, et al. Circular RNA profile identifies circPVT1 as a proliferative factor and prognostic marker in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017;388:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verduci L, Ferraiuolo M, Sacconi A, Ganci F, Vitale J, Colombo T, et al. The oncogenic role of circPVT1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is mediated through the mutant p53/YAP/TEAD transcription-competent complex. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):237. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1368-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng X, Rui S, Wang XF, Zou XH, Gong YP, Li ZH. circPVT1 regulates medullary thyroid cancer growth and metastasis by targeting miR-455-5p to activate CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-01964-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng F, Xu R. CircPVT1 contributes to chemotherapy resistance of lung adenocarcinoma through miR-145-5p/ABCC1 axis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;124:109828. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hart M, Concordet JP, Lassot I, Albert I, Del Los SR, Durand H, et al. The F-box protein beta-TrCP associates with phosphorylated beta-catenin and regulates its activity in the cell. Curr Biol. 1999;9(4):207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan Q, Zeng Z, Gong Z, Zhang W, Li X, He B, et al. EBV-miR-BART10-3p facilitates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promotes metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by targeting BTRC. Oncotarget. 2015;6(39):41766–41782. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He R, Liu P, Xie X, Zhou Y, Liao Q, Xiong W, et al. circGFRA1 and GFRA1 act as ceRNAs in triple negative breast cancer by regulating miR-34a. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36(1):145. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0614-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan CM, Wang JP, Tang YY, Zhao J, He SY, Xiong F, et al. circMAN1A2 could serve as a novel serum biomarker for malignant tumors. Cancer Sci. 2019;110(7):2180–2188. doi: 10.1111/cas.14034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu P, Mo Y, Peng M, Tang T, Zhong Y, Deng X, et al. Emerging role of tumor-related functional peptides encoded by lncRNA and circRNA. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-1147-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li P, Zhu K, Mo Y, Deng X, Jiang X, Shi L, et al. Research Progress of circRNAs in Head and Neck Cancers. Front Oncol. 2021;11:616202. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.616202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Yan Q, Mo Y, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhang S, et al. Splicing factor derived circular RNA circCAMSAP1 accelerates nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumorigenesis via a SERPINH1/c-Myc positive feedback loop. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01502-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen L, Huang C, Shan G. Circular RNAs in physiology and non-immunological diseases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2022;47(3):250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2021.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du W, Yang W, Liu E, Yang Z, Dhaliwal P, Yang BB. Foxo3 circular RNA retards cell cycle progression via forming ternary complexes with p21 and CDK2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(6):2846–2858. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du W, Fang L, Yang W, Wu N, Awan FM, Yang Z, et al. Induction of tumor apoptosis through a circular RNA enhancing Foxo3 activity. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24(2):357–370. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao L, Chang S, Xia W , Wang X, Zhang C, Cheng L, et al. Circular RNAs from BOULE play conserved roles in protection against stress-induced fertility decline. Sci Adv. 2020;6(46):eabb7426. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb7426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi L, , Liu B, , Shen D D, Yan P, Zhang Y, Tian Y, et al. A tumor-suppressive circular RNA mediates uncanonical integrin degradation by the proteasome in liver cancer. Sci Adv. 2021;7(13):eabe5043. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe5043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ouyang J, Zhong Y, Zhang Y, Yang L, Wu P, Hou X, et al. Long non-coding RNAs are involved in alternative splicing and promote cancer progression. Br J Cancer. 2022;126(8):1113–1124. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01600-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu P, Liu Y , Zhou R , Liu L, Zeng H , Xiong F, et al. Extrachromosomal circular DNA: a new target in cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:814504. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.814504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guarnerio J, Bezzi M, Jeong JC, Paffenholz SV, Berry K, Naldini MM, et al. Oncogenic role of fusion-circRNAs derived from cancer-associated chromosomal translocations. Cell. 2016;165(2):289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ouyang J, Zhang Y, Xiong F, Zhang S, Gong Z, Yan Q, et al. The role of alternative splicing in human cancer progression. Am J Cancer Res. 2021;11(10):4642–4667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan F, Zhao M, Xiong F, Wang Y, Zhang S, Gong Z, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent signalling in cancer progression and insights into cancer therapies. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-01952-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhi Y, Zhang S, Zi M, Wang Y, Liu Y, Zhang M, et al. Potential applications of N(6) -methyladenosine modification in the prognosis and treatment of cancers via modulating apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2022;e1719. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Wang J, Ge J, Wang Y, Xiong F, Guo J, Jiang X, et al. EBV miRNAs BART11 and BART17-3p promote immune escape through the enhancer-mediated transcription of PD-L1. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):866. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28479-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meng J, Chen S, Han JX, Qian B, Wang XR, Zhong WL, et al. Twist1 regulates Vimentin through Cul2 circular RNA to promote EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2018;78(15):4150–4162. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conn SJ, Pillman KA, Toubia J, Conn VM, Salmanidis M, Phillips CA, et al. The RNA binding protein quaking regulates formation of circRNAs. Cell. 2015;160(6):1125–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang R, Zhang S, Chen X, Li N, Li J, Jia R, et al. EIF4A3-induced circular RNA MMP9 (circMMP9) acts as a sponge of miR-124 and promotes glioblastoma multiforme cell tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):166. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0911-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1. Clinicopathological data of 60 NPC and 26 NPE tissues measured by qRT-PCR.

Additional file 2: Supplemental Table 2. Clinicopathological data of 159 paraffin-embedded NPC tissues and 29 non-neoplastic nasopharyngeal epithelialtissues for in situhybridization.

Additional file 3: Supplemental Table 3. Probes for fluorescence in situ hybridization and RNA pulldown, siRNAs, primers for qRT-PCR and vector construction.

Additional file 4: Supplemental Table 4. List of antibodies for immunohistochemistry, western blotting, immunofluorescence, and RNA pull-down experiments.

Additional file 5: Supplemental Table 5. The potential circPVT1-interacting proteins in CNE2 cells identified by LC-MS/MS spectrometry after pull-down with the biontin-labeled circPVT1 probe.

Additional file 6: Supplemental Table 6. The potential β-TrCP-interacting proteins in CNE2 cells identified by LC-MS/MS spectrometry after pull-down with β-TrCP antibody.

Additional file 7: Supplemental Table 7. Proteomic analysis of circPVT1-regulated proteins in CNE2 cells after transfected with the circPVT1overexpression or empty vectors, followed by LC-MS/MS spectrometry.

Additional file 8: Supplemental Table 8. Clinicopathological data of 3 NPC tissues measured by RNA pull-down.

Additional file 9: Supplemental Table 9. Clinicopathologicaldata of 30 paraffin-embedded NPC tissues for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (ISH).

Additional file 10: Figure S1. A. Thedifferentially expressed circRNAs between the high metastasis NPC cell line S18 and the low metastasis NPC cell line S26 (GSE137543, the RPM value ≥ 2and Fold changes ≥ 1.5). Circular RNA circPVT1 is highly expressed in NPC cell line S18. B. The Venn diagram of data sets GSE137543 and PRJNA391554. Circular RNA circPVT1 was identified for its high abundance in both sets of data.C. circPVT1 is mainly localized in the cytoplasm as identified by nucleoplasmic separation experiments. U6 was used as a nuclear marker and GAPDH was used as a cytoplasmic marker.

Additional file 11: Figure S2. circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC in vitroand metastasis of NPCin vivo. A-B. The expression of circPVT1 were measured in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after transfection with the circPVT1 overexpression vector or circPVT1 siRNA. PVT1 expression was not affected in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpresion or knockdown of circPVT. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant. C-D. Cell Counting Kit-8 and colony formation assays showed that circPVT1 had no effect on the growth and proliferation of NPC cells. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ns, not significant. E. H&E staining of lung metastatic tumor foci and representative images of circPVT1 expression as assessed by in situ hybridization (200×, scale bar, 50 μm). F. Images of footpad tumor formation in nude mice on day 21. Mice were injected with 1×106 CNE2 cells after overexpression or knockdown of circPVT1.G. Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for pan-cytokeratin in lymphatic tissues of mice. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Additional file 12: Figure S3. circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC cells through binding to β-TrCP. A. The secondary ion flow diagram of β-TrCP identified by mass spectrometry according to the peptide sequence (DFITALPAR) of β -TrCP.B. Schematic diagram of binding sites betweent circPVT1 and β-TrCP using the catRAPID website.The 230-280 nt of circPVT1 was predicted to bind to β-TrCP protein with high interaction score.C. The secondary structure of circPVT1 changed when 230-280 nt of circPVT1 was deleted (△circPVT1).D. Wound healing assays showed that the wild type circPVT1 but not the mutant (△circPVT1) reduced the migration abilities of CNE2 and 5-8F cells after transfected with the full-length circPVT1 or the mutant (230-280 nt deleted, △circPVT1). Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. E. Transwell invasion assays showed that the wild type circPVT1 but not mutant of circPVT1 (△circPVT1) reduced the migration abilities of CNE2 and 5-8F cells wereafter transfected with the full-length circPVT1 or the mutant (230-280 nt deleted, △circPVT1). Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant.

Additional file 13: Figure S4. The WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP interacts with circPVT1. A. The functional domain of the of β-TrCP proteins are illustrated (top), including the F-box domain and the WD40 domain. The expressing plasmids for full-length β-TrCP or truncated fragments (F-box and WD40) were constructed and confirmed using anti-Flag antibody. B. Wound healing assay showed that overexpression of β-TrCP inhibited NPC cells migration. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. C. Transwell invasion assay showed that overexpression of β-TrCP inhibited NPC cells invasion. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant.

Additional file 14: Figure S5. c-Myc is ubiquitinated substrate of β-TrCP. A. The expression of β-TrCP was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression or knockdown of circPVT1 using western blotting.B. The β-TrCP binding proteins were identified in CNE2 cells by immunoprecipitation followed by LC-MS/MS.C. The interaction of c-Myc and β-TrCP was predicted by Molecular Docking (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/). The blue part is the WD40 repeat domain of β-TrCP.D. The expression of c-Myc was examined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression of β-TrCP using western blotting.E. The ubiquitination level of c-Myc protein was determined in CNE2 and 5-8F cells after overexpression of β-TrCP and immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Myc antibody, followed by western blotting with an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

Additional file 15: Figure S6. circPVT1 promotes the migration and invasion of NPC cells by regulating cell adhesion andcytoskeleton remodeling. The 231 differentially expressed proteins regulated by c-Myc from LC-MS/MS data using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software.

Additional file 16: Figure S7. c-Myc promotes circPVT1 generation by recruiting SRSF1 to couple transcription to splicing. A. The luciferase reporter gene activity of the PVT1 promoter was analyzed in NPC cells after overexpression of c-Myc. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001. B. The binding of transcription factor c-Myc to the PVT1 promoter detected by ChIP assay. Three sites on the PVT1 promoter were identified as potential c-Myc binding sites (site 1, site 2 and site 3) using the Jasper and PROMO software. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. C. The luciferase reporter gene activity of the SRSF1 promoter was analyzed in NPC cells after overexpression of c-Myc. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001. D. The binding of transcription factor c-Myc to the PVT1 promoter detected by ChIP assay. Two sites on the PVT1 promoter were selected as the c-Myc binding sites (site 1 and site 2) using the Jasper and PROMO software. Data were represented as mean ± SD. ***, p < 0.001, ns, not significant. E. Binding of circPVT1 to β-TrCP protein was analyzed in NPC tissues after pulling-down with biotin-labeled circPVT1 probe. The biotin-labeled scrambled sequences was used as a control.F. Representative images showing the correlation between circPVT1 and the expression of c-Myc and SRSF1 in NPC tissues (top). Quantification of the correlation between circPVT1 and the expression of c-Myc and SRSF1 in NPC tissues (bottom). Magnification: 200×, Scale bar = 50 μm, 400×, Scale bar = 20 μm.

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.