Abstract

Background

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is among the most common inflammatory rheumatic diseases in older adults. Presumed risk factors include female sex, previous infections, and genetic factors. No epidemiological data on PMR in Germany have been available until now.

Methods

This review is based on publications retrieved by a selective literature search in PubMed. Moreover, the administrative incidence and prevalence of PMR in the years 2011–2019 was determined from data of the AOK Baden–Württemberg statutory health insurance carrier for insurees aged 40 and older. In addition, we quantified the number of consultations with physicians involved in the diagnosis.

Results

The annual age- and sex-standardized incidence and prevalence of PMR from 2011 to 2019 were 18.6/100 000 persons and 138.8/100 000 persons, respectively. The incidence was higher in women than in men (21.8/100 000 vs. 12.8/100 000 persons per year). 60% of the cases were diagnosed in primary care practices. The treatment of PMR with orally administered glucocorticoids usually results in a treatment response within a few days to weeks. Approximately 43% of patients experience recurrent symptoms within a year, requiring adjustment of the glucocorticoid dose. For older patients with impaired physical ability, additional non-pharmacological treatment with exercise programs plays an important role.

Conclusion

PMR usually takes an uncomplicated course under treatment and can be managed in primary care, but these patients are often multimorbid and require frequent follow-up. Along with research on the etiology of the disease, further studies are needed to identify the risk factors for a chronic course and to evaluate the potential effects of non-pharmacological measures.

cme plus

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. Participation in the CME certification program is possible only over the internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de. The deadline for submission is 16 June 2023.

After rheumatoid arthritis (RA), polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is the second most common inflammatory rheumatic disease. It occurs almost exclusively in the older population (1, 2), and women are affected 2 to 3 times more often than men (2– 4). In both sexes the incidence of PMR increases up to the age of 80 years, with a peak between the ages of 70 and 79 years (2, 4, 5). With population aging, the incidence of PMR is expected to increase in the near future (6).

Because of the frequency and relevance of PMR as encountered by general practitioners, this article aims to present an up-to-date picture of the epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of this disease. In addition, data on sex-specific incidence and prevalence rates and initially consulted medical specialties in a German patient population are presented for the first time.

Methods

For the present article, a selective literature search of PubMed was carried out. In addition, data from the statutory health insurer Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse (AOK) Baden–Württemberg were analyzed. The age- and sex-standardized “administrative” incidence and prevalence of PMR (i.e., as derived from claims data) for the period 2011–2019 were calculated, based on ICD-10 codes M35.3 (PMR) and M31.5 (giant cell arteritis [GCA] with PMR) from outpatient and inpatient care. The standard population for these calculations comprised all insured persons aged 40 years or over in the statutory health insurance (SHI) system in Germany for the year 2019 (7). Details of the selective literature search and the methodology used will be found in the eMethods section.

Epidemiology

Inzidence

During the period 2011–2019, 24 194 persons in the age group ≥ 40 years who were insured with the AOK Baden–Württemberg developed PMR. The mean age-standardized annual incidence of PMR was 17.7/100 000 insured persons aged ≥ 40 years (etable). Apart from a slight increase in 2014, there were only minor fluctuations in the incidence of PMR during the observation period.

eTable. Incidence and prevalence of PMR in insured persons aged ≥ 40 years in the SHI system in Germany, 2011–2019.

| Incidence of PMRCases/100 000 insured persons [95% CI] | Prevalence of PMRCases/100 000 insured persons [95% CI] | |||||||||||

| Total | Women | Men | Total | Women | Men | |||||||

| Raw | Stand.*1 | Raw | Stand.*2 | Raw | Stand.*2 | Raw | Stand.*1 | Raw | Stand.*2 | Raw | Stand.*2 | |

| 2011 | 18.6 [17.6; 19.6] |

17.6 [16.9; 18.3] |

24.0 [23.0; 25.1] |

22.6 [21.5; 23.6] |

12.2 [11.4; 13.0] |

11.7 [10.9; 12.6] |

115.0 [112.5; 117.4] |

107.2 [105.4; 108.9] |

152.9 [150.2; 155.6] |

139.6 [137.1; 142.2] |

69.8 [67.8; 71.8] |

68.6 [66.2; 70.9] |

| 2012 | 17.9 [17.0; 20.7] |

16.9 [16.2; 17.5] |

22.7 [21.6; 23.7] |

21.1 [20.1; 22.1] |

12.3 [11.5; 13.2] |

11.8 [11.0; 12.7] |

121.7 [119.2; 124.2] |

113.5 [111.7; 115.3] |

161.2 [158.4; 164.0] |

147.4 [144.7; 150.0] |

74.8 [72.7; 76.9] |

73.2 [70.8; 75.5] |

| 2013 | 19.6 [18.7; 20.8] |

18.5 [17.8; 19.2] |

24.4 [23.3; 25.5] |

22.5 [21.4; 23.5] |

14.2 [13.3; 15.2] |

13.7 [12.9; 14.6] |

129.9 [127.3; 132.5] |

120.6 [118.8; 122; 4] |

170.3 [167.4; 173.2] |

155.1 [152.4; 157.8] |

81.8 [79.6; 83.9] |

79.6 [77.3; 81.9] |

| 2014 | 21.4 [20.6; 22.1] |

20.1 [19.4; 20.9] |

26.6 [25.5; 27.8] |

24.7 [23.6; 25.8] |

15.2 [14.3; 16.2] |

14.7 [13.8; 15.6] |

139.6 [136.9; 142.3] |

129.3 [127.4; 131.2] |

182.2 [179.2; 185.2] |

165.6 [162.8; 168.4] |

88.9 [86.7; 91.2] |

86.0 [83.8; 88.3] |

| 2015 | 19.2 [18.2; 20.2] |

18.2 [17.5; 18.9] |

24.0 [22.9; 25.1] |

22.4 [21.4; 23.5] |

13.6 [12.7; 14.5] |

13.2 [12.3; 14.0] |

145.0 [142.3; 147.8] |

134.4 [132.5; 136.2] |

188.9 [185.8; 192.0] |

171.9 [169.0; 174.7] |

92.8 [90.5; 95.2] |

89.8 [87.5; 92.0] |

| 2016 | 18.2 [17.3; 19.2] |

17.4 [16.7; 18.1] |

23.0 [21.9; 24.1] |

21.7 [20.7; 22.7] |

12.6 [11.7; 13.4] |

12.2 [11.3; 13.1] |

146.4 [143.4; 149.1] |

136.2 [134.4; 138.1] |

190.9 [187.9; 194.0] |

174.5 [171.7; 177.4] |

93.3 [91.0; 95.6] |

90.7 [88.4; 92.9] |

| 2017 | 17.7 [16.7; 18.6] |

17.0 [16.3; 17.6] |

22.3 [21.2; 23.3] |

21.1 [20.1; 22.1] |

12.2 [11.4; 13.1] |

12.0 [11.2; 12.9] |

149.3 [146.5; 152.1] |

140.0 [138.2; 141.9] |

194.5 [191.4; 197.5] |

179.0 [176.1; 181.9] |

95.6 [93.3; 97.9] |

93.7 [91.4; 95.9] |

| 2018 | 17.2 [16.2; 18.1] |

16.7 [16.0; 17.4] |

20.7 [19.7; 21.7] |

19.8 [18.9; 20.8] |

13.0 [12.1; 13.8] |

12.9 [12.1; 13.8] |

149.9 [147.1; 152.6] |

141.7 [139.8; 143.5] |

194.2 [191.1; 197.3] |

179.9 [177.1; 182.8] |

97.2 [94.9; 99.5] |

96.1 [94.0; 98.3] |

| 2019 | 17.1 [16.2; 18.0] |

16.7 [16.1; 17.4] |

20.9 [19.9; 21.9] |

20.2 [19.2; 21.2] |

12.7 [11.9; 13.5] |

12.6 [11.8; 13.5] |

152.9 [150.1; 155.7] |

145.1 [143.2; 146.9] |

196.8 [193.7; 199.9] |

183.4 [180.5; 186.3] |

100.7 [98.3; 103.1] |

99.5 [97.3; 101.7] |

| Total | 18.6 [17.6; 19.6] |

17.7 [17.0; 18.4] |

23.2 [22.1; 24.2] |

21.8 [22.1; 24.2] |

13.1 [12.3; 14.0] |

12.8 [11.9; 13.6] |

138.8 [136.2; 141.5] |

129.8 [136.2; 141.5] |

181.3 [178.3; 184.3] |

166.3 [163.5; 169.1] |

88.3 [86.1; 90.6] |

86.3 [84.1; 88.6] |

*1 Incidence/prevalence standardized for age and sex: the standard population comprised all persons insured through the SHI in 2019 (7).

*2 Incidence/prevalence standardized for age: the standard populations comprised respectively all women and all men insured through the SHI in 2019 (7).

CI, confidence interval; PMR, polymyalgia rheumatica; SHI, statutory health insurance; stand., standardized

Incidence rates of PMR differ markedly depending on the origin of the study population, as is shown by comparisons with data from other countries. Individuals of northern European descent are more commonly affected by PMR (1, 8) than those from southern Europe (5, 6, 9). According to a review, annual incidence rates of PMR in people over 50 years of age in southern Europe were 12.7–18.7/100 000 population (5). By contrast, a US cohort study found an annual age- and sex-adjusted incidence of 63.9/100 000 in those over 50 years of age in a population of predominantly Scandinavian/northern European descent (2, 10). A cohort study from the United Kingdom found an incidence of 95.9/100 000 population, which is significantly higher than the southern European level (4). By comparison, the incidence in our study population was significantly lower, lying within the range of the southern European values.

Prevalence

Mean annual age- and sex-standardized prevalence in the period 2011–2019 was 129.8/100 000 insured persons (etable). The prevalence was observed to increase during this period. In 2011 it was 107.2/100 000 insured persons, whereas it had increased to 145.1/100 000 insured persons by 2019. A possible reason for this rise in prevalence could be a change in coding behavior (11).

In international comparisons, the prevalence determined in our study population was low. In Italy, the prevalence was 370–620/100 000 population over 50 years of age (9), whereas in the United Kingdom a much higher prevalence of 850/100 000 persons was determined (4). The prevalence of PMR seems to differ between urban and rural areas. A Canadian claims data study determined a prevalence of 754.5/100 000 in women ≥ 45 years of age living in urban areas and 1004/100 000 women in the same age group living in rural areas (12). Men ≥ 45 years of age had a lower prevalence of PMR, which also showed a difference between urban and rural regions (273.6/100 000 versus 380.7/100 000) (12). The higher prevalence rates in rural areas may possibly be explained by exposure to animals, pesticides, and grain dust, which is associated with the development of autoimmune diseases (12).

Limitations to comparing the values obtained in the present study with studies from other countries include differing inclusion criteria and data sources and differences in health care systems (6).

Sex-specific incidence and prevalence

Women are more commonly affected by PMR than men, with the sex ratio varying between 2:1 and 3:1 in the literature (4, 5). The lifetime risk of developing PMR is 2.4% for women and 1.7% for men (8, 13). Figure 1 and the eTable show the age-standardized incidence and prevalence rates of PMR in men and women. The mean age-standardized incidence of PMR was significantly higher in women than in men (21.8/100 000 versus 13.1/100 000 insured persons), and the prevalence of PMR also proved to be higher in women.

FIGURE 1.

Age-standardized incidence (top) and prevalence (bottom) of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) in men and women ≥ 40 years in the period 2011–2019. The exact values for the crude and standardized incidence and prevalence rates are shown in the eTable. The standard populations for calculating the age-standardized incidence rates were respectively all women and all men insured through the statutory health insurance (SHI) system for the year 2019 (7).

Symptoms and etiology

Typical symptoms of PMR include bilateral severe pain and stiffness in the shoulders, proximal parts of the arms, and neck (5). Less commonly, symptoms also affect the pelvic girdle and proximal parts of the thighs. Patients report persistent morning stiffness lasting 45–60 minutes, combined with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue and a general feeling of illness (5). Patients often have a considerable burden of suffering due to the severe pain.

The etiology of PMR is largely unknown. In addition, there is little that can be stated about PMR on its own, since most earlier studies investigated patients with PMR and those with GCA together, even though only 10% to 30% of patients with PMR develop GCA (2). Conversely, PMR occurs in 40% to 60% of patients with GCA during the course of the disease (2, 4, 5). Evidence suggests that a variety of endogenous and exogenous factors may favor the development of PMR (1, 2, 5, 14– 18):

Age > 50 years

Female sex

History of infections

Genetic factors.

Since PMR is almost exclusively diagnosed in over-50-year-olds, a strong influence of age may be assumed (14). Aging of the immune system – immunosenescence – also plays a part through the increased susceptibility to autoimmune processes and infections (1, 14). Elevated homocysteine values, reflecting vascular aging and inflammatory processes, have been demonstrated more frequently in patients with PMR and GCA (14).

Regarding the association between infections and the occurrence of PMR, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, parainfluenza viruses, and Chlamydia pneumoniae are thought to act as triggers in patients with a genetic predisposition (2, 5, 14– 17).

Genetic risk factors that may favor the development of PMR include polymorphisms of the HLA-DRB1 gene (1, 2, 5, 14). These genetic alterations appear to influence the severity and relapse rate of PMR (2). However, while the influence of the HLA-DRB1 genotype is known to be a risk factor for GCA, the association is not clearly established for PMR (1, 18). Polymorphisms of the cytokine IL-6 appear to play an important role, although the pathological mechanism is not understood (14).

Diagnosis

Classification criteria

In line with the German Society for Rheumatology (DGRh) clinical practice guideline for treatment of PMR (3), the classification criteria of the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) (19) can be used. For a diagnosis of PMR, the following essential criteria must be met:

Age > 50 years

Bilateral shoulder pain

Raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP)

Additionally, according to EULAR/ACR secondary criteria, PMR is present if a score of at least four out of six possible points is reached (or, with ultrasound, at least five out of eight possible points) in addition to the clinical features (table) (19). Ultrasonography of the biceps tendon and shoulder and hip joints results in a more specific EULAR/ACR classification and is recommended but is not available in the majority of general practices (19).

Table. EULAR-/ACR classification criteria for PMR (19).

| Required:1. Age > 50 years 2. New-onset bilateral shoulder pain 3. ESR ↑ and/or CRP ↑ | ||

| At least 4 or 5 points in addition to the 3 required criteria | Points 0–6 |

Points 0–8 |

| Morning stiffness > 45 minutes | 2 | 2 |

| Rheumatoid factor and/or anti-CCP negative | 2 | 2 |

| Pain in the pelvic girdle/ hip mobility ↓ | 1 | 1 |

| No other painful joints | 1 | 1 |

| Ultrasound: subdeltoid bursitis, tenosynovitis of the long head of the biceps, and/or glenohumeral joint effusion | 1 | |

| Ultrasound: trochanteric bursitis and/or hip joint effusion | 1 | |

ACR, American College of Rheumatology

Anti-CCP, antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate

CRP, C-reactive protein

EULAR, European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology

PMR, polymyalgia rheumatica

Diagnostic approach in clinical practice

PMR is primarily a clinical diagnosis, but it is often a challenge for a physician in the routine of general practice because the clinical presentation can be highly variable. According to a retrospective cohort study, the classic bilateral shoulder pain occurs in only 46% of patients in general practices (20). PMR may initially manifest unilaterally, ESR or CRP may be within the normal range, and differential diagnoses such as osteoarthritis-related complaints cannot always be definitely excluded during the diagnostic workup (21, 22). Patients are often in considerable pain and complain of feeling generally unwell. Some patients lose weight in the course of their disease and appear depressed (23). Because the course of disease can be atypical and variable, and because of multimorbidity and the existence of a large number of differential diagnoses, it may be assumed that PMR can be difficult to diagnose in the general practice setting and is often diagnosed late or perhaps only as a diagnosis of exclusion after extensive diagnostic workup (20, 24).

Rapid response to glucocorticoid therapy – within 2 weeks – and almost complete remission of symptoms within 4 weeks (25, 26) are an important, almost pathognomonic sign of PMR. It is worth mentioning that the pain symptoms respond barely or not at all to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (for example, ibuprofen). Referral to a rheumatologist or other specialist for diagnostic purposes is recommended for patients with an atypical clinical picture (for example, no bilateral shoulder pain, very high inflammatory markers) or with suspected GCA (3, 25).

Differential diagnoses

The clinical picture of PMR overlaps with those of primary shoulder disorders and RA. Primary disorders of the shoulder include subdeltoid bursitis, biceps tendinitis, rotator cuff tears, impingement, calcific tendonitis of the shoulder, and osteoarthritis. Other forms of arthritis such as spondylarthritis and enthesopathy are also worth mentioning. Using the EULAR/ACR classification criteria (table), it is somewhat easier to differentiate PMR from primary shoulder disorders than from RA (27).

The German clinical practice guideline recommends including GCA, infections, and cancer in the differential diagnosis (3). Both PMR and GCA have been suggested as possible paraneoplastic syndromes, but the results of studies on this topic so far are heterogeneous (28, 29). The authors of the German clinical practice guideline conclude that cancer screening beyond the “usual, age-appropriate level” is not necessary in patients with PMR (3). Before treatment is initiated, appropriate laboratory tests and/or diagnostic imaging should be performed to exclude relevant differential diagnoses and any contraindications to the intended treatment. Suitable diagnostic tests are listed in the Box (3).

Treatment

Drug therapy

Glucocorticoids are the standard treatment for PMR (3, 26). According to the current German clinical practice guideline, glucocorticoid therapy should be started immediately after diagnosis (3). For most patients the recommended initial dosage is 15–25 mg/day prednisolone equivalent. The dosage should not fall below 7.5 mg/day or exceed 30 mg/day, and the drug should be taken orally, in the morning if possible (3). If comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, glaucoma) are present, the initial dosage may be altered (3, 26). If the symptoms of PMR improve after glucocorticoid therapy has been started, it is recommended to slowly reduce the dosage and to adjust it individually for each patient (3, 26). In most cases, symptoms subside abruptly once glucocorticoid therapy is started. This rapid response to therapy, if it occurs, is an important element in establishing the diagnosis, particularly given the long waiting times for an appointment for further diagnostic tests and the fact that the clinical presentation can be inconclusive. If a relapse occurs, the glucocorticoid dosage can be increased again for a short time before another attempt is made to reduce it (3, 26).

Side effects are frequently seen with glucocorticoid therapy, and therefore, appropriate treatment monitoring is required (26). For patients being managed over the long term, the German clinical practice guideline (3) provides recommended intervals for follow-up visits in order to monitor:

clinical and laboratory parameters

disease activity, side effects of treatment, concomitant diseases and medication, and any relapses

the duration of treatment

In this context, the guideline on the prevention of osteoporosis by the umbrella association for osteology (“Dachverband Osteologie” [DVO]) is also relevant (3). If adverse drug reactions are observed during glucocorticoid therapy, or significant comorbidities, persistently high disease activity, or contraindications to the use of glucocorticoids are present, the latter can be combined with the immunosuppressant methotrexate (MTX), the efficacy of which in patients with PMR has been proven in randomized controlled trials (8, 18, 26). In some cases, this allows the glucocorticoid dosage to be reduced (3, 8, 18). For this reason, early use of MTX is recommended in patients with diabetes mellitus, glaucoma, or osteoporosis (8). If patients do not respond sufficiently to glucocorticoid therapy, as was reported in 3.9% of patients with PMR in a retrospective cohort study (20), or if weaning off glucocorticoid therapy is unsuccessful, MTX can likewise be used (8).

Biologicals are also being tested for the treatment of PMR in trials. They include tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α blockers, interleukin receptor blockers, and selective immunosuppressants (18). However, current guidelines advise against the use of TNF-α blockers and other biologicals because the existing evidence is inconclusive (3, 26).

Relapses are common with PMR (6, 30). According to a recent meta-analysis, 43% of patients experience relapse within 1 year of starting treatment (31). Because relapses require the glucocorticoid dosage to be increased again, the overall duration of drug therapy is extended. Especially in older patients, long-term glucocorticoid therapy is associated with adverse drug reactions. Floris et al. showed that 77%, 51%, and 25% of the study population with PMR were still taking glucocorticoids after 1, 2, and 5 years, respectively (31). In addition to increased disease activity (as represented by, for example, the level of acute-phase proteins at diagnosis, initial glucocorticoid dosage, and rate of dosage reduction), female sex and peripheral arthritis have been mentioned as possible predictors of long-term glucocorticoid therapy (3, 6, 31, 32). However, the data on this are inconclusive. Apart from the recommendations for therapy with MTX and biologicals (Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [OCEBM] evidence level 1 [systematic review with several randomized studies]), all recommendations for drug therapy listed in the German clinical practice guideline were rated at evidence level 5 (expert opinion) (3).

Referral to a rheumatologist or other medical specialist for treatment is recommended for patients with a complicated course of disease, frequent relapses, or in whom glucocorticoid therapy is contraindicated or gives rise to adverse drug effects (3, 25).

Nondrug therapy

Patients, especially older patients with impairment of physical function, should be offered exercise programs alongside drug treatment (OCEBM evidence level 5) (3). The EULAR/ACR recommendations, too, include individualized exercise programs to maintain muscle mass and function and to prevent falls, especially in patients on long-term glucocorticoid therapy (26). No studies evaluating the efficacy of nondrug therapies in patients with PMR were identified by the selective literature search.

Based on the current data, it is clear that further studies are needed to confirm risk factors for relapse and for long-term glucocorticoid therapy, and also to evaluate the efficacy of nondrug interventions in patients with PMR (31).

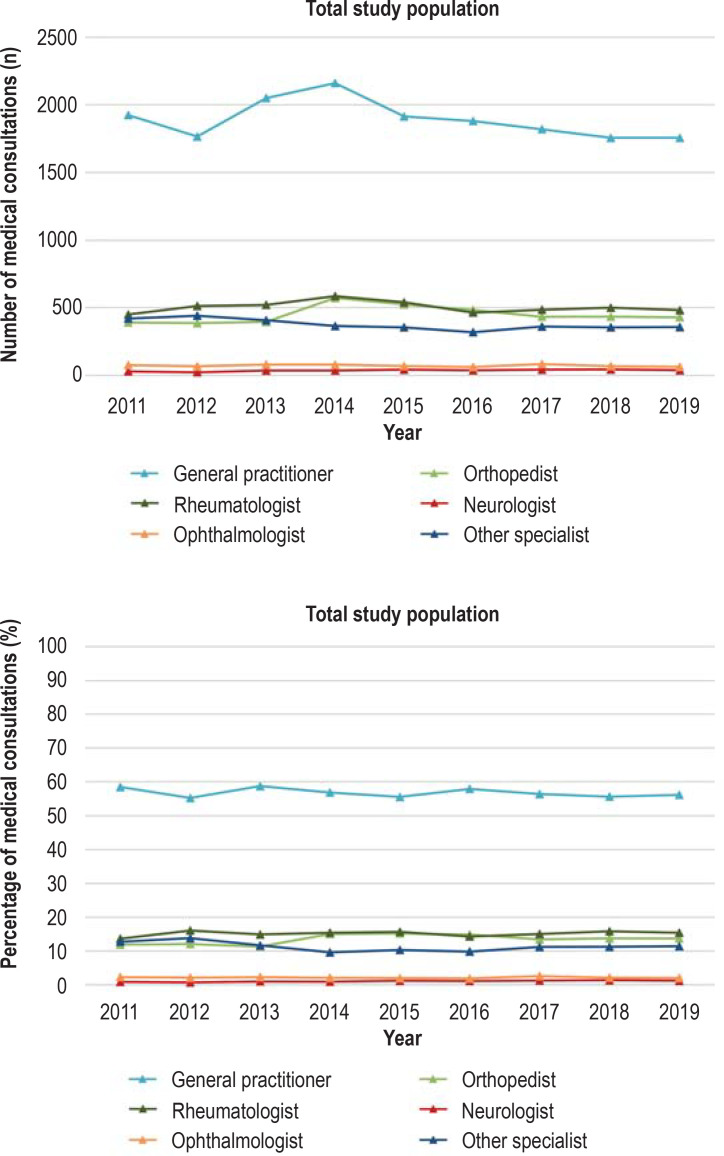

Medical specialties involved in initial care

Several medical specialties are involved in the diagnosis and treatment of PMR (3). Our literature search identified no studies from Germany that investigated the health care of patients with PMR in relation to medical specialty. On the basis of aggregated data from the AOK Baden–Württemberg, the medical specialties consulted during the incident and the following quarter by patients with new-onset PMR who were insured with the AOK Baden–Württemberg are shown in Figure 2 and the eFigure. The methodological procedure is described in the eMethods section.

Figure 2.

Number (upper) and percentage (lower) of consultations with medical specialists by persons insured with the AOK Baden–Württemberg aged ≥ 40 years with new-onset polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) in the incident and subsequent quarter, 2011–2019.

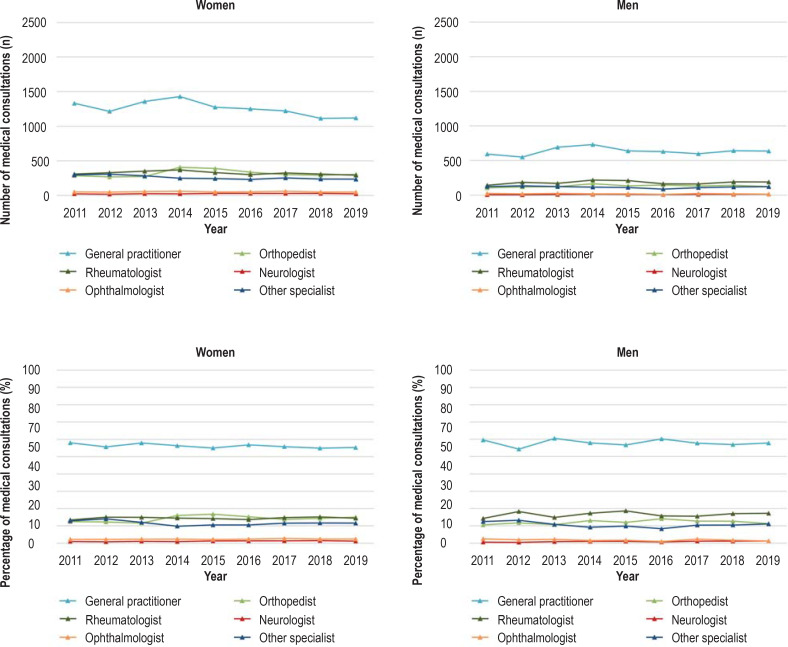

eFigure.

Number (upper) and percentage (lower) of consultations with medical specialists by persons insured with the AOK Baden–Württemberg aged ≥ 40 years with new-onset PMR in the incident and subsequent quarter, stratified by sex, 2011–2019.

PMR, polymyalgia rheumatica

General practitioners accounted for the majority of consultations (roughly 60%) by men and women with new-onset PMR, followed by orthopedists and rheumatologists (efigure). This finding is consistent with international studies that showed that it is predominantly primary care physicians who carry out the diagnosis and treatment of PMR (20, 33).

Summary

This analysis of health insurance data shows that, in Germany as elsewhere, PMR predominantly affects women and is mainly diagnosed by the general practitioner. Profound knowledge of both the diagnostic criteria and the approach to treatment is important if patients with this disease entity, with its constellation of clinical symptoms falling between various medical specialties, are not to be underserved (33). Further studies are needed to improve the health care of patients with PMR and to better understand the sex-specific differences in this disease.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Selective literature search

For this review article, we carried out a selective literature search of PubMed for the period from 1990 to September 2021. The search was limited to systematic reviews, meta-analyses, guidelines, randomized controlled trials, and cohort studies. The search terms used were: “polymyalgia rheumatica,” “aetiology,” “diagnostics,” “therapy,” “medical care,” and “specialist care.”

Epidemiological data

To determine the incidence, prevalence, and health care by medical specialty of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), we analyzed data from outpatient and inpatient medical care of persons insured with the Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse (AOK) Baden–Württemberg during the years 2011–2019. ICD-10 codes M35.3 (polymyalgia rheumatica) and M31.5 (giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica) were used for this purpose.

The data were provided by the AOK Baden–Württemberg in aggregated form, and were stratified by age and sex in accordance with previously agreed inclusion criteria as described below. Apart from the number of insured persons with PMR (stratified by sex) in the various age groups, no other information on the insured persons was provided. Incidences and prevalences (both crude and standardized for age and sex) were calculated and data on specialist medical care were analyzed by the Institute of General Practice and Interprofessional Care. All analyses were performed using the statistical software R.

Incidence of PMR

The incidence of PMR was defined using diagnoses from outpatient and inpatient medical care. A diagnosis (ICD-10: M 35.3, M 31.5) from outpatient care was taken to indicate new-onset PMR if it was coded in two quarters within a year (M2Q criterion) and was coded as a confirmed diagnosis (“G”). The two diagnoses from outpatient care recorded within 1 year could differ (e.g., first diagnosis: M35.3; second diagnosis: M31.5). The year in which the first of the two diagnoses was coded was considered the year of onset. In the data from inpatient care, a PMR diagnosis coded as main or secondary diagnosis was sufficient to count as new-onset PMR. To ensure that it was indeed an incident PMR diagnosis, a 2-year pre-observation period was set that could not include any earlier PMR diagnosis. The insured persons also had to have been continuously insured with the AOK Baden–Württemberg during this two-year period.

Prevalence of PMR

For a PMR diagnosis to be included in the prevalence data, a confirmed diagnosis (“G”) from outpatient care or a main or secondary diagnosis from inpatient care sufficed.

Standardization for age and sex

In addition to crude incidence and prevalence, the data were standardized for age and sex. The standard population comprised all persons insured in the statutory health insurance (SHI) system for the year 2019 (7).

Medical specialties providing outpatient care

To analyze which medical specialties provided care to insured persons with new-onset PMR, we used the “basic flat rates” (“Grundpauschalen”) for outpatient care billed to the AOK Baden–Württemberg on a specialty-specific basis. Unlike a doctor’s “lifetime physician number” (“LANR”), the advantage of these billing records is that they provide information on the specialty in which care was actually provided to the insured person, rather than the specialty in which the attending doctor originally trained – which may or may not be the same as his or her current area of practice. The basic flat rates for the following specialties were included: general practice, rheumatology, orthopedics, neurology, and ophthalmology. Diagnoses not made by the above-mentioned specialists were grouped together under “other medical specialty.”

To determine which medical specialties were involved in the diagnosis of PMR, we determined the frequencies of the specialist basic flat rates billed during the quarter of PMR onset and in the subsequent quarter when accompanied by a documented incident PMR diagnosis.

BOX. Further diagnostic tests in patients with symptoms typical of PMR (3).

-

Laboratory diagnosis

Rheumatoid factor

anti-CCP

CRP

ESR

Serum electrophoresis

Blood count

Blood glucose

Creatinine

Liver function parameters

Calcium

Alkaline phosphatase

Vitamin D

Dipstick urinanalysis

TSH

CK

ANA, ANCA

or tuberculosis testing

-

Diagnostic imaging

Chest X-ray

Abdominal ultrasound

Bone density scan

ANA, antinuclear antibodies

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

Anti-CCP, antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate

CK, creatine kinase; CRP, C-reactive protein

PMR, polymyalgia rheumatica

TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone

Questions on the article in issue 24/2022:

Polymyalgia rheumatica

The submission deadline is 16 July 2023. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

Which of the following groups are most often affected by polymyalgia rheumatica?

Younger women

Younger men

Older men

Older women

Children and adolescents

Question 2

Which of these symptoms are typical of polymyalgia rheumatica?

Headache with vomiting

Morning ataxia with leg stiffness

Bilateral painful shoulder and neck stiffness with fatigue

Pain in the lower legs and ankles

Unilateral painful stiffness in the fingers and toes

Question 3

In what percentage of patients with polymyalgia rheumatica does giant cell arteritis also occur?

About 2% to 5%

About 10% to 30%

About 50%

About 60% to 70%

About 95%

Question 4

Which infections are suspected to be triggers for the development of polymyalgia rheumatica in individuals with a genetic predisposition?

Influenza and pertussis

Cytomegalovirus and Haemophilus influenzae

Rubella and influenza

Parainfluenza viruses and Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Pneumococci and chlamydiae

Question 5

According to the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), which of the following criteria is required for a diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica?

Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate/elevated C-reactive protein

Bilateral pelvic pain

Absent biceps reflex

Raised blood GGT

Reduced bone density

Question 6

Which medical specialty generally provides the diagnosis and care in most cases of polymyalgia rheumatica?

Rheumatologists

Neurologists

Orthopedists

Surgeons

General practitioners

Question 7

Which drugs are used as standard treatment for polymyalgia rheumatica?

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Biologics

Biosimilars

Glucocorticoids

High-dose vitamin D

Question 8

How soon after the start of standard treatment do symptoms generally begin to improve?

Within 2 hours

Within 2 days

Within 2 weeks

Within 2 months

Within 2 years

Question 9

In the presence of which of the following comorbidities is early use of methotrexate recommended in addition to (or instead of) standard treatment in patients with polymyalgia rheumatica?

Diabetes mellitus or osteoporosis

Arrhythmia or Crohn’s disease

Psoriasis or ulcerative colitis

Hypertension or renal congestion

Cirrhosis of the liver or atherosclerosis

Question 10

According to a meta-analysis, what percentage of patients experiences a relapse of polymyalgia rheumatica within 1 year of starting therapy?

About 7%

About 13%

About 24%

About 43%

About 67%

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff.

Footnotes

Funding and support

This article was written as part of the project “Gender-sensitive prevention in different stages of life (GePL)”, a cooperative project of the AOK Baden–Württemberg, the Institute of General Practice and Interprofessional Care of the University Hospital Tübingen, the Department of Women’s Health at University Hospital Tübingen, and the University Women’s Hospital Heidelberg. The project is financed with third-party funds from the AOK Baden–Württemberg.

Conflict of interest statement The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gazitt T, Zisman D, Gardner G. Polymyalgia rheumatica: a common disease in seniors. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020;22 doi: 10.1007/s11926-020-00919-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camellino D, Giusti A, Girasole G, Bianchi G, Dejaco C. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of polymyalgia rheumatica. Drugs Aging. 2019;36:1015–1026. doi: 10.1007/s40266-019-00705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buttgereit F, Brabant T, Dinges H, et al. S3-Leitlinie zur Behandlung der Polymyalgia rheumatica. Z Rheumatol. 2018;77:429–441. doi: 10.1007/s00393-018-0476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Partington RJ, Muller S, Helliwell T, Mallen CD, Abdul Sultan A. Incidence, prevalence and treatment burden of polymyalgia rheumatica in the UK over two decades: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1750–1756. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.González-Gay MA, Matteson EL, Castañeda S. Polymyalgia rheumatica. Lancet. 2017;390:1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31825-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berti A, Dejaco C. Update on the epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes of systemic vasculitides. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018;32:271–294. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG) Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung: Mitglieder, Angehörige und Krankenstand, Jahresdurchschnitt. www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/Statistiken/GKV/Mitglieder_Versicherte/KM1_JD_2019_bf.pdf (last accessed on 10 July 2021) 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buttgereit F, Dejaco C, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B. Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2016;315:2442–2458. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manzo C. Incidence and prevalence of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR): the importance of the epidemiological context. The Italian case. Med Sci (Basel) 2019 doi: 10.3390/medsci7090092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raheel S, Shbeeb I, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Epidemiology of polymyalgia rheumatica 2000-2014 and examination of incidence and survival trends over 45 years: a population-based study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:1282–1285. doi: 10.1002/acr.23132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauhoff S, Fischer L, Gopffarth D, Wuppermann AC. Plan responses to diagnosis-based payment: evidence from Germany’s morbidity-based risk adjustment. J Health Econ. 2017;56:397–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernatsky S, Joseph L, Pineau CA, et al. Polymyalgia rheumatica prevalence in a population-based sample. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1264–1267. doi: 10.1002/art.24793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Myasoedova E, et al. The lifetime risk of adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:633–639. doi: 10.1002/art.30155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvajal Alegria G, Boukhlal S, Cornec D, Devauchelle-Pensec V. The pathophysiology of polymyalgia rheumatica, small pieces of a big puzzle. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102670. 102670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elling P, Olsson AT, Elling H. Synchronous variations of the incidence of temporal arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica in different regions of Denmark; association with epidemics of mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:112–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duhaut P, Bosshard S, Calvet A, et al. Giant cell arteritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, and viral hypotheses: a multicenter, prospective case-control study Groupe de Recherche sur l’Arterite a Cellules Geantes. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:361–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR, Lopez-Diaz MJ, et al. Epidemiology of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1454–1461. doi: 10.1002/art.24459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dejaco C, Duftner C, Buttgereit F, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B. The spectrum of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: revisiting the concept of the disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:506–515. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dasgupta B, Cimmino MA, Kremers HM, et al. 2012 provisional classification criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica: a European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:943–954. doi: 10.1002/art.34356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helliwell T, Hider SL, Mallen CD. Polymyalgia rheumatica: diagnosis, prescribing, and monitoring in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e361–e366. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X667231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manzo C, Milchert M, Natale M, Brzosko M. Polymyalgia rheumatica with normal values of both erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein concentration at the time of diagnosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58:921–923. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantini F, Salvarani C, Olivieri I, et al. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in the evaluation of disease activity and severity in polymyalgia rheumatica: a prospective follow-up study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2000;30:17–24. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2000.8366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talke M, Schmidt WA. [Polymyalgia rheumatica in daily routine practice] Z Rheumatol. 2014;73:408–414. doi: 10.1007/s00393-013-1344-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bahlas S, Ramos-Remus C, Davis P. Utilisation and costs of investigations, and accuracy of diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica by family physicians. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19:278–280. doi: 10.1007/s100670070045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matteson EL, Dejaco C. Polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166 doi: 10.7326/AITC201705020. ITC65-ITC80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dejaco C, Singh YP, Perel P, et al. 2015 recommendations for the management of polymyalgia rheumatica: a European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1799–1807. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt WA. [New classification criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica] Z Rheumatol. 2012;71:911–912. doi: 10.1007/s00393-012-1070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manzo C, Natale M. Polymyalgia rheumatica and cancer risk: the importance of the diagnostic set. Open Access Rheumatol. 2016;8:93–95. doi: 10.2147/OARRR.S116036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Partington R, Helliwell T, Muller S, Abdul Sultan A, Mallen C. Comorbidities in polymyalgia rheumatica: a systematic review. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:258. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1757-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salvarani C, Cantini F, Niccoli L, et al. Acute-phase reactants and the risk of relapse/recurrence in polymyalgia rheumatica: a prospective followup study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:33–38. doi: 10.1002/art.20901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Floris A, Piga M, Chessa E, et al. Long-term glucocorticoid treatment and high relapse rate remain unresolved issues in the real-life management of polymyalgia rheumatica: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41:19–31. doi: 10.1007/s10067-021-05819-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albrecht K, Huscher D, Buttgereit F, et al. Long-term glucocorticoid treatment in patients with polymyalgia rheumatica, giant cell arteritis, or both diseases: results from a national rheumatology database. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:569–577. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3874-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manzo C, Natale M, Traini E. Diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica in primary health care: favoring and confounding factors - a cohort study. Reumatologia. 2018;56:131–139. doi: 10.5114/reum.2018.76900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Selective literature search

For this review article, we carried out a selective literature search of PubMed for the period from 1990 to September 2021. The search was limited to systematic reviews, meta-analyses, guidelines, randomized controlled trials, and cohort studies. The search terms used were: “polymyalgia rheumatica,” “aetiology,” “diagnostics,” “therapy,” “medical care,” and “specialist care.”

Epidemiological data

To determine the incidence, prevalence, and health care by medical specialty of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), we analyzed data from outpatient and inpatient medical care of persons insured with the Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse (AOK) Baden–Württemberg during the years 2011–2019. ICD-10 codes M35.3 (polymyalgia rheumatica) and M31.5 (giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica) were used for this purpose.

The data were provided by the AOK Baden–Württemberg in aggregated form, and were stratified by age and sex in accordance with previously agreed inclusion criteria as described below. Apart from the number of insured persons with PMR (stratified by sex) in the various age groups, no other information on the insured persons was provided. Incidences and prevalences (both crude and standardized for age and sex) were calculated and data on specialist medical care were analyzed by the Institute of General Practice and Interprofessional Care. All analyses were performed using the statistical software R.

Incidence of PMR

The incidence of PMR was defined using diagnoses from outpatient and inpatient medical care. A diagnosis (ICD-10: M 35.3, M 31.5) from outpatient care was taken to indicate new-onset PMR if it was coded in two quarters within a year (M2Q criterion) and was coded as a confirmed diagnosis (“G”). The two diagnoses from outpatient care recorded within 1 year could differ (e.g., first diagnosis: M35.3; second diagnosis: M31.5). The year in which the first of the two diagnoses was coded was considered the year of onset. In the data from inpatient care, a PMR diagnosis coded as main or secondary diagnosis was sufficient to count as new-onset PMR. To ensure that it was indeed an incident PMR diagnosis, a 2-year pre-observation period was set that could not include any earlier PMR diagnosis. The insured persons also had to have been continuously insured with the AOK Baden–Württemberg during this two-year period.

Prevalence of PMR

For a PMR diagnosis to be included in the prevalence data, a confirmed diagnosis (“G”) from outpatient care or a main or secondary diagnosis from inpatient care sufficed.

Standardization for age and sex

In addition to crude incidence and prevalence, the data were standardized for age and sex. The standard population comprised all persons insured in the statutory health insurance (SHI) system for the year 2019 (7).

Medical specialties providing outpatient care

To analyze which medical specialties provided care to insured persons with new-onset PMR, we used the “basic flat rates” (“Grundpauschalen”) for outpatient care billed to the AOK Baden–Württemberg on a specialty-specific basis. Unlike a doctor’s “lifetime physician number” (“LANR”), the advantage of these billing records is that they provide information on the specialty in which care was actually provided to the insured person, rather than the specialty in which the attending doctor originally trained – which may or may not be the same as his or her current area of practice. The basic flat rates for the following specialties were included: general practice, rheumatology, orthopedics, neurology, and ophthalmology. Diagnoses not made by the above-mentioned specialists were grouped together under “other medical specialty.”

To determine which medical specialties were involved in the diagnosis of PMR, we determined the frequencies of the specialist basic flat rates billed during the quarter of PMR onset and in the subsequent quarter when accompanied by a documented incident PMR diagnosis.