In an era of heightened concern for emerging infectious diseases and bioterrorism, there is an increased need to rapidly recognize life-threatening infections. The triage nurse may be the first health care professional that encounters a patient with an unusual disease and needs to be aware of resources that can help make an informed decision. In 2003, a multi-state outbreak of monkeypox substantiated the concerns of both the general public and health care providers. Patients infected with monkeypox resembled smallpox cases and healthcare officials were simultaneously challenged to diagnose a new, rare disease while calming the community's fears.1., 2. The emergence of a new disease, combined with concerns for potential bioterrorism make the process of triage critical. A review of varicella (ie, chickenpox) with monkeypox and variola (ie, smallpox) is provided to help make the triage process more structured.

The emergence of a new disease, combined with concerns for potential bioterrorism make the process of triage critical.

Chickenpox is caused by the varicella zoster virus and is a much more common cause of a vesicular/pustular rash. Chickenpox can be confused with a more life-threatening infection. In the United States, chickenpox predominantly affects children less than 10 years of age who have not been previously immunized; only 5% of cases tend to appear in persons over 10 years of age.3 Chickenpox tends to be seasonal in the United States and usually appears in the spring.

Smallpox is caused by the variola virus and is only known to occur in humans. Variolla does not currently exist as a naturally-occurring virus, therefore any suspected case is to be reported immediately to public health authorities. Clinicians need to balance their responsibility to report a suspected case without generating false alarms. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a specific strategy for distinguishing smallpox from other causes of vesicular and pustular rash diseases. (Examples of triage resources are listed at the end of this article.)

Monkeypox is caused by the monkeypox virus that has a wide range of hosts. It appears in wild animals and has sporadically caused human disease. Prior to the spring of 2003, the pox-like illness had never been reported in the Western hemisphere. Monkeypox is transmitted to humans by consuming infected food sources or from direct contact with body fluids from an infected animal or person. Monkeypox is clinically indistinguishable from other pox-like illnesses.4

Challenge at triage

A significant number of illnesses can present with fever and rash, and infections are due to viruses, bacteria, spirochetes, rickettsiae, or the adverse effects of medications or rheumatologic diseases.3 Laboratory data are not usually available during triage and decisions will need to be based on a focused history and physical assessment. The triage nurse has to be able to identify patients with suspicious symptoms without calling false alarms. Overtriage can consume precious public health resources. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate there are approximately 1 million cases of varicella (chickenpox) in the United States each year. As few as 1000 false alarms due to the misdiagnosis of chickenpox would severely overtax the public health system's ability to investigate cases.5

The triage process can be structured to combine basic knowledge of disease processes with printed and Internet resources. By using readily available resources, triage nurses can expedite patient care, help reduce exposure to others, and avoid unnecessary concerns for patients or staff. The purpose of this discussion is to compare the more commonly occurring varicella (ie, chickenpox) with the rare diseases, smallpox and monkeypox, and to help identify significant signs and symptoms (ie, “red flags”) at triage.

Focused history and physical examination in triage

Triage is not a setting that is conducive to an extensive history or physical examination. Instead nurses have to be selective in collecting enough data to support the triage decision. To aid in the diagnosis, a structured process should be used to identify a significant history or physical findings. Table 1 lists key points to identify at triage.

Table 1.

Key points to identify in the triage of a febrile patient with a rash

| Key points to identify | |

|---|---|

| Chief complaint | • General health in last 7 to 21 days |

| • When fever started, relationship to rash, actual temperatures measured, and method used to obtain temperature | |

| • Risk for exposure to ill persons, those recently immunized | |

| • History of recent travel, camping, hiking | |

| • General immune status (ie, risk for immunocompromise) | |

| • History of immunizations | |

| • Allergies, especially eczema, psoriasis | |

| Associated symptoms | • Headache, backache, tender joints |

| • Significant lymphadenopathy | |

| • Nuchal rigidity | |

| • Photophobia | |

| • Oral lesions | |

| • Increased respiratory secretions | |

| Physical assessment | |

| Vital signs | • Fever, tachypnea, tachycardia |

| General appearance | • “Ill appearing” (has signs of systemic disease) |

| Skin and mucous membrane lesions | • Type, shape, arrangement, distribution |

Chief complaint

General health

All 3 types of pox-like illnesses have an incubation period that ranges from 1 to 3 weeks. Therefore, patients should be asked about their general health over the past 7 to 21 days. Patients presenting early during the prodromal stage will complain of fever and general malaise and the rash may not yet be present. They exhibit signs and symptoms of a systemic infection and appear ill, complaining of “flu-like” symptoms, such as numerous aches (eg, headache, backache, abdominal pain, joint pain, or tender lymph nodes). They may report chills, photophobia, nuchal rigidity, sore throat or poor swallowing in infants, increased respiratory secretions, and vomiting.

Potential exposure

The patient should be asked about obvious and obscure sources for exposure to illness. Individuals whose occupation includes with a high risk for exposure include those working with ill people, children, transportation, or retail workers. The patient should also be questioned about unusual risks for exposure, such as to exotic or wild animals, recent travel, camping, or hiking. To help identify patients with an atypical presentation, the patient's immune status should be assessed. An immunocompromised patient can have an altered ability to generate a fever or rash.3 Patients should note any allergies, especially eczema or psoriasis. Patients should be asked if they have had exposure to a documented case of chickenpox or anyone who has had recent immunizations.

Clinical course of illness

If the patient has a rash, the following information should be obtained: (1) when and where the lesions were first noticed; (2) if the lesions itch or hurt; (3) the rate and spreading pattern of lesions; (4) how the lesions have changed in appearance; (5) if the lesions are made worse by other factors, such as heat, cold, medications; and (6) what treatment has been used to control the rash.6 Past and present topical and systemic medication use should be reviewed, especially use of antipyretics, antibiotics, or steroids.

Nurses have to be selective in collecting enough data to support the triage decision.

Physical assessment

Because of time and space limitations, the triage physical assessment may have to be limited to general appearance, vital signs, and inspection of the rash. Patients may appear with enanthema (ie, eruptions upon mucous surfaces) and/or exanthema (skin eruptions). Persons with a significant infectious exanthema tend to show signs of systemic disease and present with tachypnea, tachycardia, significant lymphadenopathy, and fever. Patients with chickenpox may present with mild or no fever; monkeypox presents with a low grade fever (ie, ≥99.3 °F or ≥37.4 °C); but smallpox presents as an illness with acute onset of fever (ie, 101 °F or 38.3 °C) followed by a rash.

The skin and mucous membranes should be inspected for lesions. If found, the lesions should be described by type, shape, arrangement, and distribution.6

Type

Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 lists various types of skin lesions that are found with infectious diseases. Lesions are defined according to size, pathology, and relationship to the plane of the skin (ie, flat, elevated, or depressed). Both chickenpox and smallpox produce a rash that progresses from macules to papules, vesicles, then crusts that can scar. It is important to note that the lesions in chickenpox tend to be pleomorphic (ie, appear and progress at different stages) while smallpox lesions are monomorphic (ie, all in the same stage of development). The lesions in monkeypox tend to be monomorphic in about 80% of cases, but can be plemomorphic in 20% of cases.4

Table 2.

| Lesion | Description | Size (in diameter) | Relationship to skin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Petechiae | Deposit of blood | <0.5 cm | Flat |

| Macule | Discoloration, color varies | <1 cm | Flat |

| Papule | Solid, color varies | <0.5 cm | Elevated |

| Plaque | Circumscribed, solid; often formed by confluence of papules | >0.5 cm | Elevated |

| Nodule | Solid | >0.5 cm | Elevated |

| Wheal | Firm, transient | Can vary | Elevated |

| Vesicle | Circumscribed, fluid filled | <0.5 cm | Elevated |

| Bulla | Circumscribed, fluid filled | >0.5 cm | Elevated |

| Pustule | Circumscribed, fluid filled with leukocytes | Can vary | Elevated |

| Erosion | Does not penetrate below dermal-epidermal junction and heals without scarring | Can vary | Depressed |

| Ulcer | Focal loss of epidermis and dermis, heals with scarring | Can vary | Depressed |

Table 3.

| Syndrome | Rash | Transmission |

|---|---|---|

| Fever of 101 °F or greater occurs 1-4 days before the rash appears. | Maculopapular rash progresses to vesicles, pustules, crusts, scar. | Generally, transmission takes direct and fairly prolonged face-to-face contact or direct contact with infected bodily fluids or objects (linens). |

| Concurrent with fever, at least 1 of the following occurs: prostration, headache, backache, chills, vomiting, or severe abdominal pain. The fever may drop with rash onset. | The lesions in smallpox tend to appear monomorphic (all one stage). | Not infectious until rash develops. |

| Classic smallpox lesions are deep seated, firm to touch, round, and well circumscribed vesicles or pustules; umbilicated appearance. | Infectious until all lesions have scabbed over. | |

| The rash distribution begins in the mouth and throat spreads to face, arms, and legs, then to hands/palms and feet/soles. | ||

| Within 24 hours of onset, rash usually spreads to cover the body. | ||

| Once the rash starts the patient is now contagious | ||

| As the rash appears, the fever usually abates and the patient “feels better.” | ||

| On the third day, the rash becomes raised lesions; by the fourth day, the lesions fill with a thick opaque fluid and often have a depression in the center. After approximately 5 days, a pustular rash develops. | ||

| By the end of the second week after the has rash appeared, most of the sores have scabbed over. |

Table 4.

| Prodrome | Rash | Transmission |

|---|---|---|

| Prodrome phase consists of patients typically experiencing low-grade fever, headache, nonproductive cough, chills, lymphadenopathy, and drenching sweats. | Rash does not occur in all patients. If rash develops it will develop within 1 to 10 days after prodrome. | Primary route of transmission from infected animal to human following close contact. Animals found to be carriers in United States are prairie dogs, Gambian giant rats. |

| Rash is popular that progresses through stages of vesiculation, pustulation, umbilication, and crusting. | Skin-to-skin transmission from an infected person's lesions has been documented. | |

| In some patients, early lesions have become ulcerated. |

Table 5.

| Prodrome | Rash | Transmission |

|---|---|---|

| None or very mild fever. | Lesions are superficial vesicles, described as “dewdrops on a rose petal.” | Infectious until all lesions have scabbed over. |

| None or mild concurrent symptoms. | Most infectious in the 48-hour period before rash develops. |

Shape

Skin lesions can appear in a variety of shapes, such as round, annular (ring-shaped), or umbilicated. The lesions in chickenpox, smallpox, and monkeypox all appear as round and circumscribed. Smallpox lesions are characterized by firm, deep-seated vesicles or pustules.

Arrangement

Lesions may appear grouped or disseminated. They are disseminated in chickenpox, smallpox, and monkeypox.

Distribution

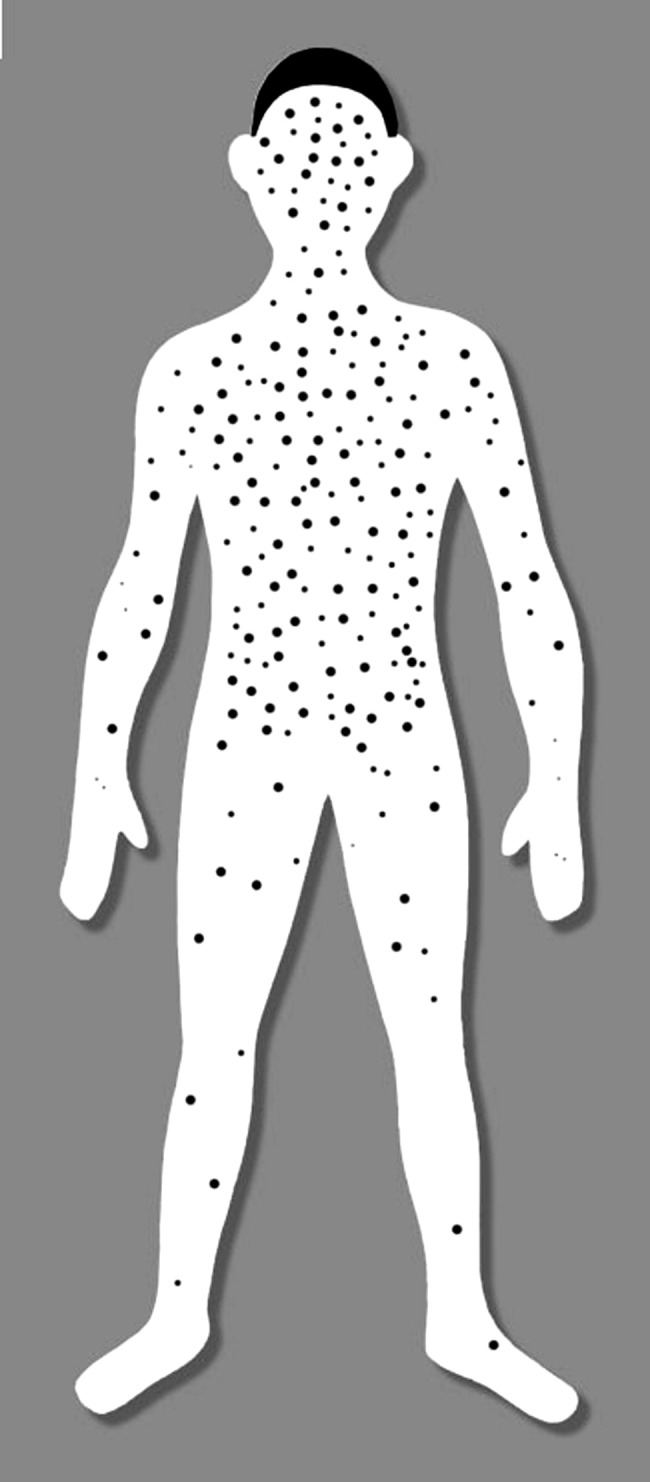

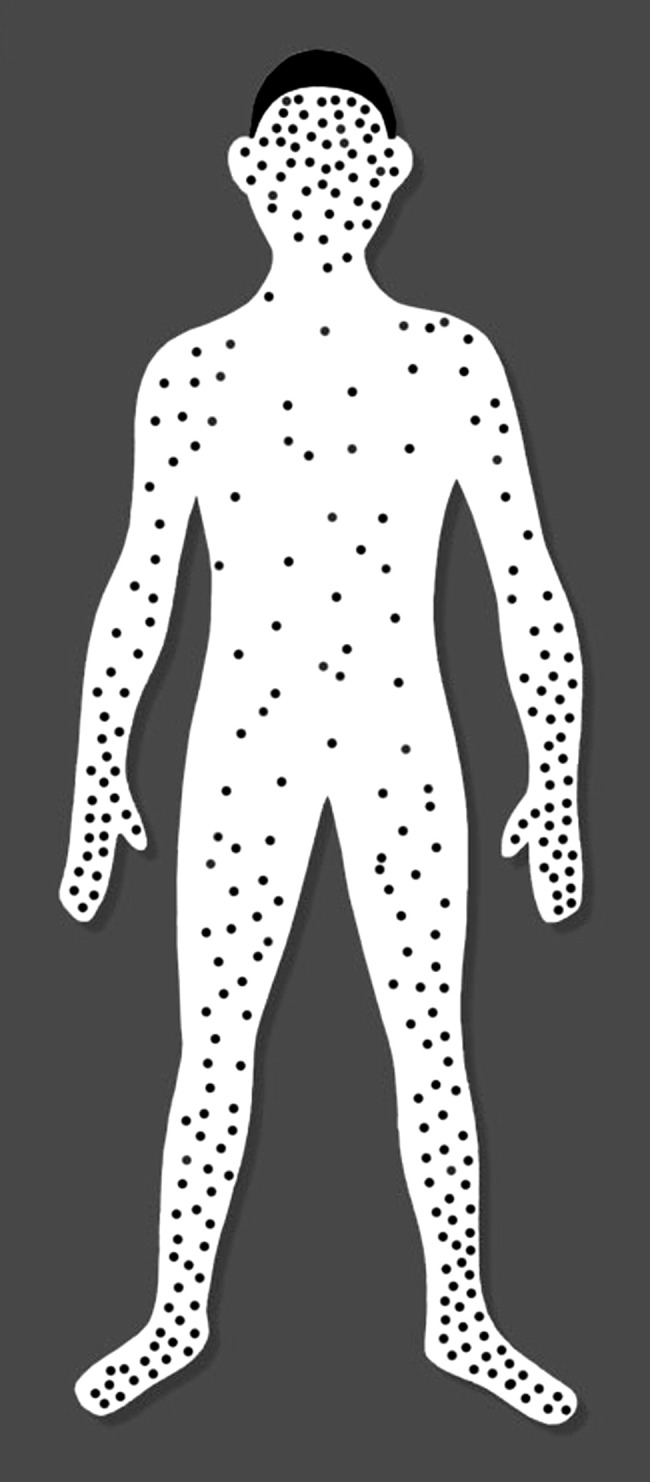

In the early stages of disease, the lesions will appear in patterns and spread in a characteristic direction (eg, centripetal = moves from periphery towards center; centrifugal = moves from center to periphery). Chickenpox lesions appear as blister-like lesions, usually on the face, scalp, or trunk, progressing from the center and moving distally (ie, in a centripetal pattern) ( Figure 1). Patients may rarely have lesions on their palms or soles. Smallpox lesions move in a centrifugal pattern ( Figure 2), typically beginning in the oropharynx, face, and forearms, then spreading to the trunk and legs.5., 7. Monkeypox lesions are distributed similar to smallpox in 80% of cases and similar to chickenpox in fewer cases (i.e., 5%).4

In the early stages of disease, the lesions will appear in patterns and spread in a characteristic direction

Figure 1.

Centripetal pattern of skin lesion distribution commonly seen with chickenpox. (Source: Center for Disease Control and Prevention Smallpox Risk Evaluation Help available at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/diagnosis/riskalgorithm/evalhelp.asp)

Figure 2.

Centrifugal pattern of skin lesion distribution commonly seen with smallpox. (Source: Center for Disease Control and Prevention Smallpox Risk Evaluation Help available at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/diagnosis/riskalgorithm/evalhelp.asp)

Resources for triage

If the nurse suspects that the patient has a significant infection, institutional standardized protocols should be immediately implemented. Triage protocols and diagnostic aids created by the CDC and updated regularly are available from the Internet, can be printed or stored in a computer file for ready access.

(Note: Readers may easily access the Web sites when reading this article online by simply clicking on the URL links.)

Chickenpox

The CDC has created the following resource aids to help clinicians identify exanthemas that might be chickenpox.

-

▪

Varicella Disease & Herpes Zoster, Clinical Questions & Answers is available at http://www.cdc.gov/nip/diseases/varicella/faqs-clinic-disease.htm

-

▪

Images of Diseases, Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Only contains visual images of varicella that can be accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/nip/diseases/disease_images.htm#Varicella

-

▪

Evaluating Patients with Acute Generalized Vesicular or Pustular Rash Illnesses is a slide presentation that compares smallpox and chickenpox (available at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/training/overview/pdf/differentialdiagnosis.pdf). Slides 15 through 22 discuss the similarities and differences between the 2 infections.

Monkeypox

-

▪

The CDC has developed guidelines to define suspected, probable, and confirmed cases of chickenpox. The guidelines, Updated Interim Case Definition for Human Case of Monkeypox, are available at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/monkeypox/casedefinition.htm

Smallpox

-

▪

Smallpox Case Definitions are available at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/diagnosis/casedefinition.asp

-

▪

Acute, generalized vesicular or pustular rash illness protocol is a chart that helps to analyze if the patient is at risk for smallpox (available at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/diagnosis/rashtestingprotocol-chart1.asp).

-

▪

Evaluating patients for smallpox (available at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/diagnosis/evalposter.asp) is a poster that uses an algorithm of a systematic approach to evaluate any patient with a generalized rash.

-

▪

Evaluate a Rash Illness Suspicious for Smallpox (available at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/diagnosis/riskalgorithm/index.asp), is an online interactive risk evaluation algorithm to be used with patients with a suspicious rash but no current knowledge of smallpox exposure. The tool helps clinicians to immediately access visual guides and to calculate the risk for smallpox.

-

▪

Worksheet: evaluating patients for smallpox is a downloadable standard worksheet (available at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/diagnosis/pdf/spox-patient-eval-wksheet.pdf). This form can be used to collect standard information on any case being evaluated for smallpox. The form is also available through state health departments.

-

▪

Smallpox Overview for Clinicians is available at (http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/clinicians.asp)

Other sources

-

▪

CDC Clinician Information Line is available for health care providers who prefer to speak to a person directly (877) 554-4625

-

▪

A visual review of skin lesions is available online from Public Health Image Library at http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/

Summary

The immediate and correct recognition of an infectious exanthema can be aided with a focused history and minor assessment. False alarms can consume health care resources and create unnecessary anxiety. Clinicians can use specific references to not only help with educating staff, but to ensure a more accurate diagnosis and trigger notification of appropriate infectious disease protocols. The authors recommend that all emergency departments have a process in place to immediately isolate suspicious cases until a more thorough medical workup can be performed.

References

- 1.Reynolds G. Why were doctors afraid to treat Rebecca McLester? New York Times Magazine. April 18, 2004, Late Edition, Section 6, p 32, Col 1.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Monkeypox Investigation Team Update: multi-state outbreak of monkeypox–Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio and Wisconsin, 2003. MMWR. 2003;52:642–646. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKinnon H.D., Howard T. Evaluating the febrile patient with a rash. Am Fam Phys. 2000;62:804–816. http://www.aafp.org/afp/20000815/804.html Available from: Accessed May 4, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiGiulio D.B., Eckburg P.B. Hyman monkeypox: an emerging zoonosis. Lancet. 2004;4:14–25. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00856-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seward J. Rash illness evaluation. Available from: http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/training/webcast/dec2002/files/rash-illness-eval.ppt. Accessed May 4, 2004.

- 6.Fitzpatrick T.B., Johnson R.A., Wolff K., Suurmond D. 4th ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. Color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology, common & serious disease. [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Brien K.K., Higdon M.L., Halverson J.J. Recognition and management of bioterrorism infections. Am Fam Phys. 2003;67:1927–1934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferri F.F., editor. Practical guide to the care of the medical patient. 5th ed. Mosby; St. Louis: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lofquist J.M., Weimert N.A., Hayney M.S. Smallpox: a review of clinical disease and vaccination. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60:749–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berman J.G., Henderson D.A. Current concepts: diagnosis and management of smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1300–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson D.A., Inglesby T.V., Bartlett J.G., Ascher M.S., Eitzen E., Jahrling P.B., et al. Smallpox as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA. 1999;281:2127–2137. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.22.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moran G.J., Worth W.E., Karras D.J., Pesik N.T. Smallpox vaccination for emergency physicians: Joint Statement of the AAEM and SAEM. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:351–352. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(03)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartlett J., Borio L., Radonovich L., Mair J.S., O'Toole T., Mair M., et al. Smallpox vaccination in 2003: key information for clinicians. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:883–902. doi: 10.1086/374792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovell R.D. Distinguishing smallpox from chickenpox. ED Manage. 2002;14(Suppl 1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer H., Perrichot M., Stemmler M., Emmerich P., Schmitz H., Varaine F., et al. Outbreaks of disease suspected of being due to human monkeypox virus infection in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2001. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2919–2921. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.2919-2921.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.State of Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services . Division of Public Health; Madison (WI): June 8, 2003. Official health alert. Monkeypox-like orthopox virus infections in humans having direct contact to prairie dogs; Wisconsin, Illinois, and Indiana. [Google Scholar]