Abstract

A method for one-stage rapid identification of four orthopoxvirus species pathogenic to humans based on multiplex polymerase chain reaction (MPCR) was developed. Five pairs of oligonucleotide primers—one, genus-specific; and the rest, species-specific for variola, monkeypox, cowpox, and vaccinia viruses, respectively—were used concurrently for MPCR assay of orthopoxvirus DNAs. Specificity and sensitivity of the method developed were evaluated using DNAs of 57 orthopoxvirus strains, including the DNAs isolated from human case clinical materials.

Keywords: Variola virus, Monkeypox virus, Cowpox virus, Vaccinia virus, Multiplex PCR, Detection

1. Introduction

The genus Orthopoxvirus of the family Poxviridae includes species pathogenic to humans, such as variola (VARV), monkeypox (MPXV), cowpox (CPXV), and vaccinia (VACV) viruses.

VARV causes smallpox and is an exclusively anthroponotic agent. This is the first and yet single infectious disease that was eradicated due to the international medical program under the aegis of WHO [1]. Now, VARV is regarded as a potential bioterrorism agent [2], [3].

Natural reservoir of MPXV is rodents. Human monkeypox resembles the clinical course of smallpox that was prevalent on the African continent, and is recorded predominantly in Central and Western Africa [1], [4]. The lethal cases as well as human-to-human transfer were recorded mainly within the unvaccinated cohort [4], [5].

CPXV displays the widest host range among the orthopoxviruses. Generally, human cowpox is a benign disease manifesting itself by isolated local lesions [6], [7], [8]. In the case of immunocompromised persons, the disease may have a generalized form with lethal outcome [9]. Human cowpox is recorded in the majority of European countries and several countries of Asia and Latin America. Rodents (the main natural reservoir) or home pets and cattle (bridging hosts) represent the main sources of human CPXV infection [6].

VACV, used for vaccinating humans against orthopoxvirus infections, can be transmitted to man accidentally by contact with a vaccinee.

Cessation of anti-smallpox vaccination since 1980 resulted gradually in formation of a large population cohort susceptible not only to VARV, but also to other orthopoxviruses. This formed an opportunity for ever increasing spread of previously relatively mild infections of monkeypox- and cowpox-types in the human population [4], [5], [6]. In particular, for the first time outbreaks of human cowpox in Brazil (ProMed, Archive number 20030111.0095) and human monkeypox in the USA in 2003 were recorded [10].

The potential increase in the degree of danger of orthopoxvirus infections for people requires development of efficient methods for rapid detection and identification of orthopoxviruses pathogenic to humans.

The conventional biological and serological methods used now appeared insufficiently effective for identification and rapid diagnostics of orthopoxviruses [1], [11]. The biological analysis takes too much time (3–6 days) and involves handling of special viral pathogens. The serological methods, as a rule, allow only for a genus-level identification; moreover, their sensitivities are frequently insufficient for assaying clinical samples [11]. The methods based on genomic analysis may be regarded as an effective and efficient approach to diagnosing viral infections. It was demonstrated [12], [13] that restriction assay of viral DNAs provided a highly reliable species-level identification of orthopoxviruses. However, this is a time-consuming method and requires propagation of the virus, its purification, and specialized equipment.

The advent of the method of DNA fragment amplification by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [14] formed the background for designing various techniques appropriate for rapid identification of orthopoxviruses. So far, application of PCR for detection of orthopoxviruses using common oligonucleotide primers to the regions of genes encoding hemagglutinin [15], A-type inclusion protein [16], and homologue of tumor necrosis factor receptor [17] is described. In all these techniques, the DNA fragments obtained by PCR are hydrolyzed with certain restriction endonucleases and separated by electrophoresis; the resulting patterns of subfragments allowed orthopoxviruses to be identified at a species level. However, when a large enough set of isolates of an orthopoxvirus species was analyzed, heterogeneity of their restriction fragment patterns became apparent, making interpretation of the results obtained rather ambiguous.

The real-time PCR assays developed so far [18], [19], [20] allows only VARV to be discriminated from other orthopoxvirus species.

Recently, a three-dimensional polyacrylamide-gel microchip containing arrays of oligonucleotides specific to the viral CrmB gene was used to discriminate different species of orthopoxviruses [21]. Another kind of oligonucleotide microarray on plain glass slides involving viral gene C23L/B29R was designed for discrimination between orthopoxviruses pathogenic to humans [22].

In this work, we developed a method of (MPCR) assay of orthopoxviruses pathogenic to humans. This method displays a high specificity and sensitivity of the analysis. The essence of the method designed is that the selected unique oligonucleotide primers allow orthopoxviruses to be identified at a species level in one stage. Five pairs of oligonucleotide primers (four pairs for VARV, MPXV, VACV, and CPXV, respectively, and one genus-specific pair) were used in a united PCR producing amplicons of various lengths specific of each orthopoxvirus species in question. The genus-specific pair was used as an internal PCR control for the presence of orthopoxvirus DNA in the sample and discrimination from other genera of poxviruses.

For several CPXV strains, the MPCR developed produces an additional amplicon specific of VACV along with the amplicons characteristic of this species. This data is consistent with existence of different cowpox virus subtypes [1], [23].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Viral DNAs

The poxvirus DNAs used in this work are listed in Table 1 .

Table 1.

List of poxvirus strains whose DNA was used in multiplex PCR assay

| Orthopoxvirus species | Strain | Country of isolation | Source of strain or DNA | Sizes of PCR fragments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variola virus | Brazil 128* | Brazil | 1 | 203 |

| 292 | ||||

| Brazil 131* | Brazil | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| Butler | UK | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| Ind-3a | India | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| India 164* | India | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| Congo-2 | Congo | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| Congo-9 | Congo | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| Kuw-5 | Kuwait | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| Aslam* | Pakistan | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| Khateen* | Pakistan | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| M-Abr-60 | Russia | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| M-Sok-60 | Russia | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| M-Sur-60 | Russia | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| 12/62 | Tanzania | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| Ngami | Tanzania | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| Semat | Tanzania | 1 | 203 | |

| 292 | ||||

| Monkeypox virus | CDC# v78-I-3945 | Benin | 2 | 292 |

| 581 | ||||

| CDC# v79-I-005 | Zaire | 2 | 292 | |

| 832 | ||||

| CDC# v97-I-004 | Zaire | 2 | 292 | |

| 832 | ||||

| Congo-8 | Zaire | 2 | 292 | |

| 832 | ||||

| Zaire 96-I-16 | Congo | 2 | 292 | |

| 832 | ||||

| CDC# v70-I-187 | Liberia | 2 | 292 | |

| 581 | ||||

| Copenhagen | Denmark | 2 | 292 | |

| 492 | ||||

| Patwadanger | India | 1 | 292 | |

| 492 | ||||

| Elstree 3399 | The Netherlands | 1 | 292 | |

| 492 | ||||

| CVI-78 | The Netherlands | 1 | 292 | |

| 492 | ||||

| LIVP | Russia | 1 | 292 | |

| 492 | ||||

| ??-63 | Russia | 1 | 292 | |

| 492 | ||||

| Western Reserve | USA | 1 | 292 | |

| 492 | ||||

| Chambon St-Yves Menard | France | 1 | 292 | |

| 492 | ||||

| Subspecies of vaccinia virus: buffalopox virus | BP-1 | India | 1 | 292 |

| 492 | ||||

| Cowpox virus | EP-5 | Austria | 1 | 292 |

| 421 | ||||

| OPV 89/4 | Germany | 3 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| OPV 90/1 | Germany | 3 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| OPV 90/2 | Germany | 3 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| OPV 90/5 | Germany | 3 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| OPV 91/1 | Germany | 3 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| OPV 98/1 | Germany | 3 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| GRI-90 | Russia | 1 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| Puma M-73 | Russia | 1 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| EP-1 | Germany | 1 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| EP-2 | Germany | 1 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| EP-3 | Germany | 1 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| EP-4 | Germany | 1 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| EP-8 | Germany | 1 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| EP-267 | Germany | 1 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| OPV 89/3 | Germany | 3 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| OPV 90/4 | Germany | 3 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| OPV 98/5 | Germany | 3 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| Ham-85 | Germany | 1 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| EP-6 | The Netherlands | 292 | ||

| 421 | ||||

| 1 | 492 | |||

| EP-7 | The Netherlands | 1 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| Turk-74 | Turkmenia | 1 | 292 | |

| 421 | ||||

| 492 | ||||

| Ectromelia virus | MP-1 | Germany | 3 | 292 |

| MP-2 | Germany | 3 | 292 | |

| 4908 | The Netherlands | 3 | 292 | |

| 33221 | The Netherlands | 3 | 292 | |

| Other poxvirus genera | ||||

| Leporipoxvirus | ||||

| Shope fibroma virus | Kasza | Canada | 4 | – |

| Myxoma virus | Lausanne | Switzerland | 5 | – |

| Avipoxvirus | ||||

| Fowlpox virus | FP9 | UK | 6 | – |

| Yatapoxvirus | ||||

| Tanapox virus | TNP | USA | 2 | – |

Notes: (1) collection of SRC VB vector; the strains were received from S.S. Marennikova, Institute for Viral Preparations, Ministry of Public Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia. Other viral DNAs were received; (2) from J.J. Esposito, CDC. Atlanta, USA; (3) from H. Meyer, Munich, Germany; (4) from D. Evans, Guelph, Canada; (5) from G. McFadden, London, Canada; (6) from M. Skinner, Newbury, UK; and (*) DNA of variola viruses was isolated from scabs of human cases, obtained in 1970–1975.

2.2. Clinical samples

Scabs from skin lesions of smallpox human cases infected in 1970–1975 were used for analysis. These samples are deposited with the Russian Collection of Variola Virus (SRC VB Vector). All the work with the samples containing VARV was performed in a specialized high-level biocontainment laboratory certified for this type of work by the Russian control agency and WHO representatives. In addition, scabs from human skin lesions formed after vaccination with VACV strain L-IVP in 2000 were used.

2.3. Experimental samples

Pocks from chorioallantoic membranes (CAMs) of chick embryos infected with VACV or CPXV were used.

2.4. Isolation of viral DNAs

Pocks from CAMs or fragments of skin scabs isolated from human cases were homogenized in the solution containing 200 μl of lysing buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl pH=8.0, 100 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, and 1% SDS) and 20 μl of proteinase K solution (10 mg/ml) to incubate for 10 min at 56 °C. The mixture was centrifuged for 7 min at 18,000g to remove the insoluble fraction. The supernatant was supplemented with 400 μl of phenol–chloroform mixture (1: 1), mixed in a Vortex for 1 min, and centrifuged at 450g for 1 min. The aqueous phase was transferred into clean tubes to extract the residual phenol with isoamyl alcohol. To precipitate DNA, 3 M sodium acetate solution pH 5.5 (1: 10 v/v) and two volumes of 96% ethanol were added. The mixture was centrifuged followed by removal of the aqueous phase, drying of the sediment, and its dissolution in water.

2.5. Oligonucleotide primers

Nucleotide sequences of DNAs of various orthopoxviruses—VARV strains India-1967 [24], Bangladesh-1975 [25], and Garcia-1966 [26]; MPXV strain Zaire-96-I-16 [27]; CPXV strain GRI-90 [28]; and VACV strains Copenhagen [29], Ankara [30], and Tian-tan (EMBL accession no. AF095689)—were aligned using the program Alignment Service [31] to search for potential species-specific regions that were further used to calculate oligonucleotide primers for MPCR. The putative primer pairs were further analyzed by the program Oligo 3.3 [32]. Then, the primer sequences calculated for VARV, MPXV, and CPXV were tested for the presence of homology or complementarity to one another and the other poxvirus sequences available in GenBank. The absence of homology with other orthopoxvirus species and poxvirus genera was one of the criteria for choosing the appropriate oligonucleotides. Upon experimental testing, a pair of primers highly conservative for particular orthopoxvirus species and failing to produce any amplicons from DNAs of the rest orthopoxvirus species was selected for each species in question. The primer sequences and calculated lengths of the corresponding amplicons are listed in Table 2 . The primers used were synthesized in an automatic ABI-394 DNA/RNA (Applied Biosystems, USA) synthesizer.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in MPCR

| Virus | Genomic region (ORF) | Primer sequence | Length of amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VACV | F4L (genus-specific region) | 5′-cgttggaaaacgtgagtccgg-3′ | 292 |

| 5′ attggcgttttttgcagccag-3′ | |||

| CPXV | B9R | 5′-atcagatggaattatctctcacccg-3′ | 421 |

| 5′ gataatttgatccatctcgtccacc-3′ | |||

| MPXV | E5R | 5′-atgttgatattaataatcgtattgtggtt-3′ | 581 (West African) |

| 5′-aaagtcaatacactcttaaagattctcaa-3′ | 832 (Central African) | ||

| VARV | B11R-B12R | 5′-catccgatattattgtaaccacaatg-3′ | 203 |

| VACV | C9L | 5′-ggtgtagtcgtaatcgtaatcgtctaatt-3′ 5′-aagatactctatgatagttgtaaaacatttaacatc-3′ | 492 |

| 5′-cccaacatttctaaatctcctcgt-3′ |

ORF, open reading frame; ORF names are given according to the designations conventionally accepted for each virus (see Fig. 1). VACV, vaccinia virus strain Copenhagen [29]; CPXV, cowpox virus strain GRI-90 [28]; MPXV, monkeypox virus strain Zaire-96-I-16 [27]; VARV, variola virus strain India-1967 [24].

2.6. MPCR assay

Series of various primer concentrations (0.2, 0.3, 0.5, and 1 μM), deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP) concentrations (0.8, 1, and 1.5 mM), and concentrations of Mg2+ ions (1.5, 2, and 3 mM) were tested to optimize the multiplex PCR.

The amplification with a hot start was performed in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (PE Biosystems) amplifier using the following mode: a preliminary heating for 2 min at 93 °C; 30 cycles of 30 s at 93 °C, 45 s at 50 °C, and 2 min at 72 °C; and the final stage of 10 min at 72 °C. The reaction mixture (50 μl) contained 60 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 25 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM of each dNTP, 1 μM of each species-specific primer, 0.3 μM of each genus-specific primer, 2 AU of Taq polymerase, and DNA template. The amplicons were stored at 4 °C until used for electrophoretic analysis. Electrophoresis was performed in horizontal plates using 2% agarose in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris–Ac pH 8.0 and 1 mM EDTA) and either 100 bp or 1 kbp DNA marker (SibEnzyme, Novosibirsk, Russia).

All the procedures were performed under conditions of a minimal risk of contamination with exogenous DNA. Separate rooms and filter-equipped tips as well as negative and positive controls at all the stages of PCR assay confirmed the efficiency of these preventive measures.

3. Results and discussion

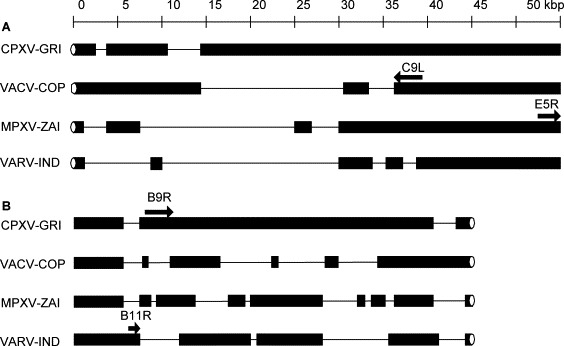

When selecting the primers for design of the system for MPCR assay, we based on the following criteria: species-specific amplification of viral DNAs and obtaining of amplicons with distinct lengths characteristic of individual orthopoxvirus species. For this purpose, we performed a multiple alignment of the available nucleotide sequences of various orthopoxvirus strains, which allowed us to discover putative unique regions of orthopoxvirus DNAs for each species in question (Fig. 1 ). Taking into account a limited number of the known genomic sequences and occurrence of intraspecies heterogeneity of orthopoxviruses in their DNA structures [1], [15], [16], [17], [33], we calculated various combinations of oligonucleotide primers for each selected region of the viral genomes and tested them experimentally using a set of DNAs isolated from various strains of the orthopoxviruses in question.

Fig. 1.

Graphical alignment of (a) left and (b) right species-specific genomic regions of cowpox virus strain GRI-90 (CPXV-GRI), vaccinia virus strain Copenhagen (VACV-COP), monkeypox virus strain ZAI-96 (MPXV-ZAI), and variola virus strain India-1967 (VARV-IND). Arrows indicate directions and lengths of the ORFs wherein species-specific amplification was performed. ORF names are given above the arrows. Black blocks represent coding sequences of viral DNAs. Fine lines represent deletions in viral genomes relative to other viruses; ellipses, terminal hairpins of viral DNAs.

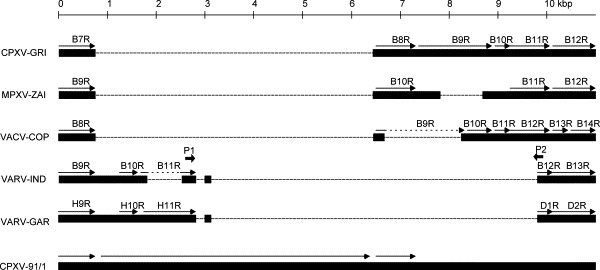

It was recently reported [34] that DNAs of certain CPXV isolates contained the nucleotide sequence of the so-called VARV-specific ORFs B10R-B11R [24], [25], [26]. We sequenced this region of viral DNA (will be published elsewhere) and demonstrated that the genomic region of CPXV strains EP-2 and OPV-91/1 in question contained an extended continuous ORF (Fig. 2 ). Basing on the sequencing data, oligonucleotide primers for VARV-specific PCR were chosen (Table 2, Fig. 2). As for CPXV strains carrying an extended ORF in this genomic region, PCR performed under standard conditions fails to produce any amplicon due to a large distance between the primers in question (over 6 kbp, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Graphical alignment of DNA sequences of various orthopoxviruses—cowpox virus strain GRI-90 (CPXV-GRI), monkeypox virus strain ZAI-96 (MPXV-ZAI), vaccinia virus strain Copenhagen (VACV-COP), and variola virus strains India-1967 (VARV-IND) and Garcia-1966 (VARV-GAR)—with the corresponding genomic region of CPXV strain 91/1 (CPXV-91/1), containing ‘variola virus-specific’ sequence. Arrows indicate directions and lengths of the ORFs. ORF names are given above the arrows. Fine lines represent deletions in viral genomes relative to other viruses. P1 and P2 are oligonucleotide primers used for specific amplification of VARV DNAs.

The final sequences of primer pairs (Table 2) were determined upon numerous experiments by means of fitting from a set of primers.

Primers to the region of the gene encoding small subunit of ribonucleotide reductase (ORF F4L for VACV strain Copenhagen; Table 2), highly conservative for and specific of orthopoxviruses, were calculated as an internal positive control and for discrimination from poxviruses of other genera in the samples assayed.

Five primer pairs (Table 2) were used simultaneously for multiplex PCR assay; of them, pair 1 is genus-specific and gives the amplicon with a length of 292 bp. The rest primer pairs are species-specific, giving the amplicons of the lengths listed in Table 2. The optimal concentrations of primers providing for amplification of the orthopoxvirus genomic regions in question amounted to 0.3 μM for the genus-specific primers and 1 μM for the species-specific primers. This ratio of primer pairs provides more efficient species-specific PCRs compared with the genus-specific reaction. Experiments demonstrated that amplification of the genus-specific fragment by MPCR stopped at a lower dilution of VARV, CPXV or VACV DNA samples compared with species-specific amplifications (data not shown).

Simultaneous use of several primer pairs requires a specialized fitting of bivalent ion concentrations in the PCR buffer. Correspondingly, we tested various concentrations of Mg2+ ions. In addition, the concentration of Mg2+ ions depends on free dNTPs; therefore, we tested the concentrations of MgCl2 and dNTPs concurrently: 0.8, 1, and 1.2 mM dNTPs and 1.5, 2, and 2.5 mM MgCl2. A maximal yield of the reaction products with a minimal non-specific background were achieved at 1 mM dNTPs and 2 mM MgCl2.

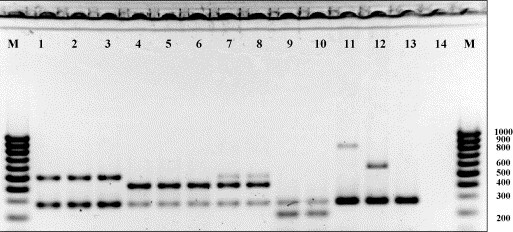

An example of MPCR assay of a set of orthopoxvirus strains of various species, shown in Fig. 3 , demonstrates that all species of the orthopoxviruses pathogenic to humans yield amplicons with their own characteristic lengths. For several CPXV strains, the MPCR designed produces three DNA fragments, namely, genus-specific, CPXV-specific, and VACV-specific (in minor proportion) (Fig. 3, Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Electrophoretic separation in 2% agarose of the amplicons produced by MPCR using four pairs of oligonucleotide primers for species-specific identification of orthopoxviruses: (1) VACV strain LIVP; (2) VACV strain Patwadanger; (3) VACV strain CVI-78; (4) CPXV strain OPV-91/1; (5) CPXV strain GRI-90; (6) CPXV strain EP-5; (7) CPXV strain EP-2; (8) CPXV strain OPV-98/5; (9) VARV strain Ind-3a; (10) VARV strain Butler; (11) MPXV strain CDC# v79-I-005; (12) MPXV strain CDC# v78-I-3945; (13) Ectromelia virus strain 4908; (14) negative control; and M, DNA marker (lengths in bp are shown to the right).

The ORF E5R of MPXV carries several species-specific deletions [27], [35]. Moreover, Central African and Western African MPXV strains differ in these deletions [35]. This specific feature of MPXV genome allowed us to design a pair of primers capable of amplifying the DNA segment of MPXV not only in a species-specific, but also in a subtype-specific manner (Fig. 3, Table 1).

Ectromelia virus (ECTV), belonging to the genus Orthopoxvirus and non-pathogenic to humans, may be considered as an internal negative species-level control, as the MPCR assay developed produces only the genus-specific amplicon (Fig. 3).

To verify the specificity of the method developed, DNAs of 57 strains of various orthopoxvirus species (Table 1) were assayed. The mixture of primers used produced no amplicons from DNAs of unrelated poxviruses-rabbit myxoma virus and Shope fibroma virus, both belonging to the genus Leporipoxvirus; fowlpox virus, genus Avipoxvirus; and tanapox virus, genus Yatapoxvirus.

Analysis of clinical samples containing VARV (scabs from skin lesions) as well as VACV or CPXV experimental samples obtained from pocks on CAMs did not detect any unexpected amplicons. Thus, the developed version of MPCR assay allows for a detecting reliably and identifying in one stage the orthopoxviral species VARV, MPXV, and VACV. In the case of CPXV, some strains produce one species-specific amplicon in MPCR, whereas other CPXV strains form in addition the DNA fragments specific of VACV (Table 1). Thus, when it is important to exclude a concurrent presence of CPXV and VACV in samples, additional analyses involving other genetic loci, for example, by an aforementioned PCR assay variants, are necessary [15], [16], [17].

VACV strain L-IVP, purified in sucrose density gradient, with the known titer determined in cell culture was used to test the sensitivity of the overall procedure, starting from DNA isolation to MPCR. Before DNA isolation, the virus was diluted so that a known number of plaque-forming units (PFU) were present in 50 μl of solution. Experiments demonstrated (data not shown) that the virus is detected reliably using the DNA isolation technique and MPCR described in the samples containing 20–30 PFU. For monkeypox virus the species-specific amplicons are the longest in the MPCR described here (see Table 2) and therefore for this species reliable detection is possible in the samples containing 80–100 PFU.

Acknowledgements

Authors are sincerely grateful to A.A. Guskov and E.B. Sokunova for cultivation of variola viruses; G.V. Kochneva for cultivation of cowpox and vaccinia viruses; M.V. Mikheev and I.N. Babkina for isolation of viral DNAs; and H. Meyer, J.J. Esposito, G. McFadden, D. Evans, and M. Skinner, for kind provision of viral DNA samples. The work was supported by ISTC (grant No. 1987p).

References

- 1.Marennikova S.S., Shchelkunov S.N. KMK Scientific Press; Moscow: 1998. Orthopoxviruses pathogenic for humans. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breman J.G., Henderson D.A. Current concepts: diagnosis and management of smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1300–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spencer R.C., Lightfoot N.F. Preparedness and response to bioterrorism. J Infect. 2001;43:104–110. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2001.0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breman J.G. In: Scheld W.M., Craig W.A., Hughes J.M., editors. vol. 4. ASM Press; Washington: 2000. Monkeypox: an emerging infection for humans? pp. 45–67. (Emerging infections). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukinda V.B., Mwema G., Kilundu M., Heymann D.L., Khan A.S., Esposito J.J. Re-emergence of human monkeypox in Zaire in 1996, Monkeypox epidemiologic working group. Lancet. 1997;349:1449–1450. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63725-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer H., Schay C., Mahnel H., Preffer M. Characterization of orthopoxviruses isolated from man and animals in Germany. Arch Virol. 1999;144:491–501. doi: 10.1007/s007050050520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schupp P., Pfeffer M., Meyer H., Burck G., Kolmel K., Neumann C. Cowpox virus in a 12-year-old boy: rapid identification by orthopoxvirus-specific polymerase chain reaction. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wienecke R., Wolff H., Schaller M., Meyer H., Plewig G. Cowpox virus in an 11-year-old girl. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:892–894. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(00)90265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czerny C.P., Eis-Hübinger A.M., Mayr A., Schneweis K.E., Pfeiff B. Animal poxviruses transmitted from cat to man: current event with lethal end. J Vet Med. 1991;1338:421–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1991.tb00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC Update: multistate outbreak of monkeypox—Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin. MMWR. 2003;52:642–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsevich G.R., Rudyuk S.N., Ryjov K.A., Andjaparidze O.G. Evolution of methods of laboratory diagnosis of orthopoxvirus infection. Vopr Virusol. 1996;41:195–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esposito J.J., Obijeski J.F., Nakano J.H. Orthopoxvirus DNA: strain differentiation by electrophoresis of restriction endonuclease fragmented virion DNA. Virology. 1978;89:53–66. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackett M., Archard L.C. Conservation and variation in orthopoxvirus genome structure. J Gen Virol. 1979;45:683–701. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-45-3-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bej A.K., Mahbubani M.H., Atlas R.M. Amplification of nucleic acids by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and other methods and their applications. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1991;26:301–334. doi: 10.3109/10409239109114071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ropp S.L., Jin Q.I., Knight J.C., Massung R.F., Esposito J.J. Polymerase chain reaction strategy for identification and differentiation of smallpox and other ortopoxviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2069–2076. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2069-2076.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer H., Ropp S.L., Esposito J.J. Gene for A-type inclusion body protein is useful for a polymerase chain reaction assay to differentiate orthopoxviruses. J Virol Methods. 1997;64:217–221. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(96)02155-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loparev V.N., Massung R.F., Esposito J.J., Meyer H. Detection and differentiation of old world orthopoxviruses: restriction fragment length polymorphism of the crmB gene region. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:94–100. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.1.94-100.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espy M.J., Cockerill F.R., Meyer F.R., Bowen M.D., Poland G.A., Hadfield T.L., Smith T.F. Detection of smallpox virus DNA by LightCycler PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1985–1988. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.6.1985-1988.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibrahim M.S., Kulesh D.A., Saleh S.S., Damon I.K., Esposito J.J., Schmaljohn A.L., Jahrling P.B. Real-time PCR assay to detect smallpox virus. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3835–3839. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3835-3839.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olson V.A., Laue T., Laker M.T., Babkin I.V., Drosten C., Shchelkunov S.N., Niedrig M., Damon I.K., Meyer H. Real-time PCR system for detection of orthopoxviruses and simultaneous identification of smallpox virus. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1940–1946. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.1940-1946.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapa S., Mikheev M., Shchelkunov S., Mikhailovich V., Sobolev A., Blinov V., Babkin I., Guskov A., Sokunova E., Zasedatelev A., Sandakhchiev L., Mirzabekov A. Species-level identification of orthopoxviruses with an oligonucleotide microchip. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:753–757. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.3.753-757.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laassri M., Chizhikov V., Mikheev M., Shchelkunov S., Chumakov K. Detection and discrimination of orthopoxviruses using microarrays of immobilized oligonucleotides. J Virol Methods. 2003;112:67–78. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(03)00193-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gubser C., Hue S., Kellam P., Smith G.L. Poxvirus genomes: a phylogenetic analysis. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:105–117. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19565-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shchelkunov S.N., Resenchuk S.M., Totmenin A.V., Blinov V.M., Marennikova S.S., Sandakhchiev L.S. Comparison of the genetic maps of variola and vaccinia viruses. FEBS Lett. 1993;327:321–324. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massung R.F., Liu L.-I., Qi J., Knight J.C., Yuran T.E., Kerlavage A.R., Parsons J.M., Venter J.C., Esposito J.J. Analysis of the complete genome of smallpox variola major virus strain Bangladesh—1975. Virology. 1994;201:215–240. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shchelkunov S.N., Totmenin A.V., Loparev V.N., Safronov P.F., Gutorov V.V., Chizhikov V.E., Knight J.C., Parsons J.M., Massung R.F., Esposito J.J. Alastrim smallpox variola minor virus genome DNA sequences. Virology. 2000;266:361–386. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shchelkunov S.N., Totmenin A.V., Babkin I.V., Safronov P.F., Ryazankina O.I., Petrov N.A., Gutorov V.V., Uvarova E.A., Mikheev M.V., Sisler J.R., Esposito J.J., Jahrling P.B., Moss B., Sandakhchiev L.S. Human monkeypox and smallpox viruses: genomic comparison. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:66–70. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shchelkunov S.N., Safronov P.F., Totmenin A.V., Petrov N.A., Ryazankina O.I., Gutorov V.V., Kotwal G.J. The genomic sequence analysis of the left and right species-specific terminal region of a cowpox virus strain reveals unique sequences and a cluster of intact ORFs for immunomodulatory and host range proteins. Virology. 1998;243:432–460. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goebel S.J., Johnson G.P., Perkus M.E., Davis S.W., Winslow J.P., Paoletti E. The complete DNA sequence of vaccinia virus. Virology. 1990;179:247–266. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antoine G., Scheiflinger F., Dorner F., Falkner F.G. The complete genomic sequence of the modified vaccinia Ankara strain: comparison with other orthopoxviruses. Virology. 1998;244:365–396. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Resenchuk S.M., Blinov V.M. Alignment service: creation and processing of alignments of sequences of unlimited length. Comput Appl Biosci. 1995;11:7–11. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/11.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breslauer K.J., Frank R., Blocker H., Marky L.A. Predicting DNA duplex stability from the base sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3746–3750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esposito J.J., Knight J.C. Orthopoxvirus DNA: a comparison of restriction profiles and maps. Virology. 1985;143:230–251. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer H., Neubauer H., Pfeffer M. Amplification of variola virus-specific sequences in German cowpox virus isolates. J Vet Med. 2002;49:17–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2002.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Douglass N.J., Richardson M., Dumbell K.R. Evidence for recent genetic variation in monkeypox viruses. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:1303–1309. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-6-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]