Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess the effect of a multimodal prehabilitation program on perioperative outcomes in colorectal cancer patients with a higher postoperative complication risk, using an emulated target trial (ETT) design.

Patients and Methods

An ETT design including overlap weighting based on propensity score was performed. The study consisted of all patients with newly diagnosed colorectal cancer (2016–2021), in a large nonacademic training hospital, who were candidate to elective colorectal cancer surgery and had a higher risk for postoperative complications defined by: age ≥ 65 years and or American Society of Anesthesiologists score III/IV. Intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of prehabilitation compared with usual care on perioperative complications and length of stay (LOS).

Results

Two hundred fifty-one patients were included: 128 in the usual care group and 123 patients in the prehabilitation group. In the ITT analysis, the number needed to treat to reduce one or more complications in one person was 4.2 (95% CI 2.6–10). Compared with patients in the usual care group, patients undergoing prehabilitation had a 55% lower comprehensive complication score (95% CI −71 to −32%). There was a 33% reduction (95% CI −44 to −18%) in LOS from 7 to 5 days.

Conclusions

This study showed a clinically relevant reduction of complications and LOS after multimodal prehabilitation in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery with a higher postoperative complication risk. The study methodology used may serve as an example for further larger multicenter comparative effectiveness research on prehabilitation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1245/s10434-022-12623-9.

The goal of prehabilitation of cancer patients indicated for surgery is to improve recovery after treatment to reduce the severity of treatment-related complications that may cause significant disability.1 Prehabilitation can be offered as a single modality intervention, consisting of only exercise training, or as a multimodal intervention including exercise training as well as nutrition assessment and reduction of intoxications (smoking and alcohol use) and psychological stress.2 Although mortality after colorectal cancer surgery has already decreased significantly in recent years, older patients and patients with a higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score are still prone to postoperative complications.3,4 Therefore, these patients in particular could benefit from prehabilitation.

While the prehabilitation concept appears promising, there is conflicting scientific evidence for its effectiveness.5–9 Several RCTs have been performed, showing different effects of multimodal prehabilitation, ranging from meaningful changes in postoperative functional walking capacity and significantly improved postoperative clinical outcomes,10,11 to no effect on postoperative outcomes.12

Because these RCTs are usually performed under ideal circumstances, including only a selected group of patients, this can compromise external validity.11–13 Studies based on observational, real-world data could be of added value to better understand for whom prehabilitation may be of benefit. However, as a result of the absence of a strict research protocol and randomization, the outcomes of observational studies are more prone to bias.14

To minimize the impact of bias in observational studies for intended effects, Hernán and Robins described the emulated target trial (ETT) design, in which observational data are used to mimic an RCT as close as possible.15 The ETT enables a more accurate comparison of clinical trial and real-world data, because it applies the same eligibility criteria as the target trial (RCT) and reduces biases by a well-defined time zero.15 Moreover, ETTs can typically include a more heterogeneous group of patients.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of a multimodal prehabilitation program compared with usual care on perioperative outcomes in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery with a higher postoperative complication risk, using an ETT design.

Patients and Methods

Data Sources

Patients diagnosed with newly onset colorectal cancer, between January 2016 and July 2021, in a large nonacademic training hospital (the Jeroen Bosch Hospital, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands) were identified from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR). Prehabilitation was not offered in this hospital before 1 June 2017. All patients with a multidisciplinary team (MDT) consultation before this time were therefore included in the control group. Before prehabilitation was offered to every patient meeting the inclusion criteria from November 2018, several pilot studies were conducted. To reduce bias, all patients with an MDT consultation between 1 June 2017 and 31 October 2018 were excluded. Furthermore, patients with an MDT consultation date between 16 March 2020 and 8 June 2020 or a part of the preoperative period (time between MDT consultation and surgery) within this period were also excluded because prehabilitation was not offered during this period as a result of COVID-19. Patients with MDT dates between 1 November 2018 and 15 March 2020, and 9 June 2020 and 31 July 2021 are therefore included in the intervention group.

On the basis of electronic patient records, information on comorbidities, polypharmacy, substance use, physical status, and adherence to the prehabilitation program was collected. Information on ethnicity was not available.

Study Design

The ETT framework was used to design this single-center study.15 The target trial protocol, modified from two previous RCT protocols,11,16 and the emulation of this target trial is summarized in Supplement 1.

The medical ethics committee region Brabant (file number NW2021-02) advised that this study did not fall within the remit of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO).

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria defined in the target trial protocol could be applied to the ETT protocol (Supplement 1). Candidacy for elective surgery was determined based on the preoperative MDT consultation involving surgeons, oncologists, a radiologist, a radiotherapist, a pathologist, and a nurse practitioner discussing the need for surgery. The exclusion criteria were implemented with some deviations from the target protocol (Supplement 1) because the target trial using observational data was emulated. Because there was no measure to define patients with an unstable cardiac or respiratory disease, patients were excluded from the ETT protocol if doubts were described about the operability (on the basis of patients’ physical condition, not tumor characteristics) during MDT consultation. In the target trial protocol, patients with locomotor limitations precluding exercise training and patients with cognitive deterioration impeding adherence to the program were excluded. This was translated to the ETT protocol as exclusion of patients who were wheelchair dependent or who had dementia registered as a comorbidity, respectively. The ability to offer prehabilitation for a minimum of 4 weeks was translated into the ETT protocol as exclusion of patients for whom the first MDT consultation took place after surgery or for whom there was no MDT consultation at all. Patients were also excluded if tumor characteristics, such as an obstructive tumor, a bleeding carcinoma, a signet ring cell carcinoma, and/or severe tumor related pain, did not allow for a 4 week waiting period. Hospital admission at the time of MDT consultation that continued after MDT consultation was also a reason to exclude patients. Finally, patients were excluded in the ETT protocol if there was no access to the electronic patient record because the patient opted out of research use of their patient data. In case patients were treated more than once for newly onset colorectal cancer during the study period, only the first tumor treatment period was taken into analysis to avoid duplicates.

Treatment Strategies

Usual care was compared with prehabilitation. Usual care consisted of anemia treatment as indicated (using intravenous iron medication or blood transfusion per protocol), a 30-min preoperative assessment with the physical therapist for breathing exercises, and a preoperative calculation of the nutritional assessment score (SNAQ)17 In case the SNAQ-score ≥ 3, patients were referred for a consultation with a dietician. In addition, patients were accompanied from diagnosis to the end of the treatment trajectory (including both surgery and chemotherapy) by a specialized oncology nurse who provided detailed information about the diagnosis and treatment process, as well as psychological support. On indication, a psychologist was consulted.

The multimodal prehabilitation consisted of case management of a specialized oncology nurse and anemia treatment, comparable to the usual care group. In addition, patients were strongly advised to reduce intoxications (smoking cessation and reduction of alcohol intake). During intake with the physical therapist, a personalized exercise program was made for each participant. Moreover, each patient received a tailored nutritional advice from a dietician.

The exercise program designed by the physical therapist contained two components: (1) three times a week, for at least 3 weeks, a 60 min high-intensity training in the hospital supervised by a physical therapist, (2) four times a week for at least 60 min, a nonsupervised low-intensity endurance training at home (e.g., walking or biking). During the intake with a dietician, patients received tailored nutritional advice to achieve a total protein intake of 1.9 g per kg of lean body mass per day. Patients were also advised to take an additional 0.4 g per kg protein, within 1 h before high-intensity training and daily before bedtime. If necessary, protein shakes were prescribed to achieve this intake. During prehabilitation, patients were followed by a dietician with a final consultation at the end of the program.

As of 2019, all patients were screened on frailty, using the G8 questionnaire.18 In case of a G8 score ≤ 14, patients were referred to a geriatrician for advice on delirium prevention and medication review.

Postoperative management, based on the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols, was the same for all patients both in the usual care and prehabilitation group.19

Treatment Assignment

Ideally, in an RCT design, patients should have been blindly randomized to the usual care or prehabilitation group. However, due to the observational character of the data for this study, randomization was impossible. For the ETT, treatment assignment was based on the MDT consultation date. Eligible patients were assigned to the usual care group if MDT consultation took place before 1 June 2017 and to the prehabilitation group if MDT consultation took place after 31 October 2018 (excluding the COVID period). Next, we calculated the propensity of treatment assignment to the prehabilitation or control condition based on the predictors of treatment assignment that we could identify, and weighted our analysis for this propensity.

Time Zero and Follow-up

Time zero was defined in the ETT protocol as the time of MDT consultation, at which a decision was made to schedule elective colorectal cancer surgery. As in the target trial protocol, the follow-up lasted up to 30 days after surgery in the ETT protocol, and in case no surgery was performed after inclusion, patients were followed for 2 months after time zero.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of patients with at least one complication (defined as yes/no complication) during follow-up. A distinction was made between complications that occurred during the total follow-up period as the primary outcome, and during the preoperative and postoperative periods as secondary outcomes. A preoperative complication was defined as any deviation from the normal preoperative course, not related to preexisting comorbidity, including but not limited to colorectal cancer (CRC)-related complications (e.g., ileus or new-onset anemia after inclusion requiring blood transfusion), prehabilitation-related complications (e.g., loss of consciousness during physical exercise or acute renal failure as a result of protein suppletion), and adverse events such as traffic accident injuries. A postoperative complication was defined as any deviation from the normal postoperative course, classified following the standards of the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA) and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM).20

To take into account both the number and severity of postoperative complications, the comprehensive complication score (CCS) was calculated as the secondary outcome.21 Finally, the length of stay (in days) and number of readmissions was compared between the standard care and the prehabilitation groups.

Causal Contrasts

To compare the two treatment strategies, both an intention-to-treat effect as well as the per-protocol effect was estimated in the target trial. The intention-to-treat effect in the ETT included all patients eligible for prehabilitation, as well as patients who did not start the program because of another reason not described in the exclusion criteria (e.g., not motivated to participate, prehabilitation not in hospital setting, or holiday before surgery). The per-protocol effect for both the target and the ETT consisted of all patients who had at least nine consultations with the physical therapist and two consultations with the dietician.

Statistical Analysis

Unweighted baseline characteristics of the patients in the prehabilitation versus the standard care group were compared using the student’s t or Mann–Whitney U tests for numerical variables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, depending on data distribution.

After exploring missing data patterns and mechanisms, missing data for potential confounders were assumed to be missing at random. Missing data was mainly from the lack of electronic patient files in the beginning of 2016. To deal with missing data, baseline values of all potential confounders were imputed using a multiple imputation approach based on fully conditional specification (MICE package, R).22

The primary analysis followed an intention-to-treat format as specified under causal contrasts. Overlap weighting (OW), based on propensity scores (PS), was performed to reduce the impact of treatment selection bias and potential confounding factors.23 To compare the balance of baseline covariates between the standard care and prehabilitation groups, standardized mean differences were computed for the baseline covariates both before and after applying OW.24,25 To further characterize the effect of compliance with prehabilitation, a per-protocol analysis was performed.

All reported p-values are two-sided, and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was conducted using R4.1. Supplement 2 contains further information on the statistical analysis.

Results

Participants

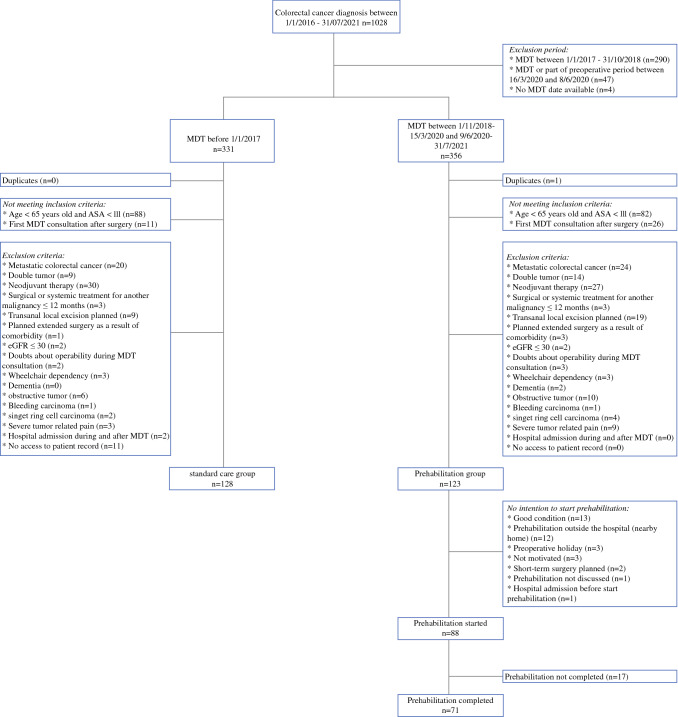

Between January 2016 and July 2021, 1028 patients were diagnosed with colorectal cancer (Fig. 1). After applying both inclusion and exclusion criteria, 251 patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis (128 in the standard care group and 123 in the prehabilitation group). Baseline characteristics of the prehabilitation and control groups are presented in Table 1. Patients in the prehabilitation group were older than patients in the control group (p = 0.003) and less likely to use alcohol (p < 0.001), and had a greater incidence of anemia at the time of inclusion (p = 0.012). The median duration of time between inclusion and surgery was 23 [interquartile range (IQR), 17–30] days in the standard care group and 38 (IQR, 30–48) days in the prehabilitation group.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the intention-to-treat population, stratified by usual care group and prehabilitation

| Usual care (n = 128) | Prehabilitation (n = 123) | Total (n = 251) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Median age, years (IQR) | 72 (68–76) | 75 (71–80) | 73 (69–79) | 0.003 |

| Gender | 0.052 | |||

| Male | 75 (58.6%) | 57 (46.3%) | 132 (52.6%) | |

| Civil status | 0.259 | |||

| Partnership | 94 (73.4%) | 92 (74.8%) | 186 (74.1%) | |

| Single | 18 (14.1%) | 23 (18.7%) | 41 (16.3%) | |

| Widowed | 15 (11.7%) | 8 (6.5%) | 23 (9.2%) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.319 | |||

| < 18.5 | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.8%) | |

| 18.5–25 | 48 (37.5%) | 45 (36.6%) | 93 (37.1%) | |

| 25–30 | 51 (39.8%) | 43 (35.0%) | 94 (37.5%) | |

| ≥ 30 | 27 (21.1%) | 35 (28.5%) | 62 (24.7%) | |

| Smoking | 0.496 | |||

| Never | 58 (45.3%) | 50 (40.7%) | 108 (43.0%) | |

| Former | 58 (45.3%) | 65 (52.8%) | 123 (49.0%) | |

| Current | 11 (8.6%) | 8 (6.5%) | 19 (7.6%) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Alcohol use | < 0.001 | |||

| Never | 49 (38.3%) | 60 (48.8%) | 109 (43.4%) | |

| < 1/week | 28 (21.9%) | 8 (6.5%) | 36 (14.3%) | |

| ≥ 1/week < 2/daily | 26 (20.3%) | 42 (34.1%) | 68 (27.1%) | |

| ≥ 2/daily | 23 (18.0%) | 13 (10.6%) | 36 (14.3%) | |

| Missing | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.8%) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.621 | |||

| 0 | 66 (51.6%) | 58 (47.2%) | 124 (49.4%) | |

| 1 | 26 (20.3%) | 32 (26.0%) | 58 (23.1%) | |

| 2 | 24 (18.8%) | 19 (15.4%) | 43 (17.1%) | |

| ≥ 3 | 12 (9.4%) | 14 (11.4%) | 26 (10.4%) | |

| Polypharmacy (≥ 5 drugs) | 0.154 | |||

| Yes | 51 (39.8%) | 60 (48.8%) | 111 (44.2%) | |

| ASA index | 0.171 | |||

| I | 10 (7.8%) | 6 (4.9%) | 16 (6.4%) | |

| II | 74 (57.8%) | 61 (49.6%) | 135 (53.8%) | |

| III | 40 (31.3%) | 54 (43.9%) | 94 (37.5%) | |

| IV | 4 (3.1%) | 2 (1.6%) | 6 (2.4%) | |

| MET score | 0.438 | |||

| < 3 | 2 (1.6%) | 3 (2.4%) | 5 (2.0%) | |

| 3–6 | 43 (33.6%) | 72 (58.5%) | 115 (45.8%) | |

| >3 | 40 (31.3%) | 47 (38.2%) | 87 (34.7%) | |

| Missing | 43 (33.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 44 (17.5%) | |

| SNAQ score | 0.950 | |||

| ≥ 3 | 15 (11.7%) | 16 (13.0%) | 31 (12.4%) | |

| Missing | 27 (21.1%) | 13 (10.6%) | 40 (15.9%) | |

| Anemia at inclusion | 0.012 | |||

| Yes | 48 (37.5%) | 66 (53.7%) | 114 (45.4%) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Tumor characteristics | ||||

| Tumor localisation | 0.056 | |||

| Colon | 61 (47.7%) | 76 (61.8%) | 137 (54.6%) | |

| Sigmoid | 48 (37.5%) | 37 (30.1%) | 85 (33.9%) | |

| Rectum | 19 (14.8%) | 10 (8.1%) | 29 (11.6%) | |

| Tumor stage | 0.114 | |||

| I | 36 (28.1%) | 33 (26.8%) | 69 (27.5%) | |

| II | 57 (44.5%) | 42 (34.1%) | 99 (39.4%) | |

| III | 35 (27.3%) | 48 (39.0%) | 84 (33.1%) | |

| Stoma at inclusion | 0.165 | |||

| Yes | 2 (1.6%) | 6 (4.9%) | 8 (3.2%) |

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, MET score Metabolic Equivalent of Task score, SNAQ score Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire score

Only one patient, in the prehabilitation group, underwent open surgery; all other patients underwent laparoscopic colectomy. Conversion during surgery was needed in five patients (4%) in the standard care group and four (3%) in the prehabilitation group. In both the usual care group and the prehabilitation group, most patients underwent right hemicolectomy [53 (41%) and 60 (49%) patients, respectively]. Stoma creation was performed in 23 patients (18%) in the usual care group and 7 patients (6%) in the prehabilitation group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Operative characteristics of the intention-to-treat population, stratified by usual care group and prehabilitation

| Usual care (n = 128) | Prehabilitation (n = 123) | Total (n = 251) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical approach | |||

| Open | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Laparoscopic | 128 (100%) | 122 (99.2%) | 250 (99.6%) |

| Conversion | |||

| Yes | 5 (3.9%) | 4 (3.3%) | 9 (3.6%) |

| Type of surgery | |||

| Right hemicolectomy | 53 (41.4%) | 60 (48.8%) | 113 (45.0%) |

| Left hemicolectomy | 5 (3.9%) | 16 (13.0%) | 21 (8.4%) |

| Transverse colectomy | 3 (2.3%) | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (1.6%) |

| Subtotal colectomy | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Anterior/sigmoid resection | 47 (36.7%) | 35 (28.5%) | 82 (32.7%) |

| Low anterior resection | 16 (12.5%) | 7 (5.7%) | 23 (9.2%) |

| Abdominoperineal resection | 3 (2.3%) | 3 (2.4%) | 6 (2.4%) |

| Stoma creation | |||

| Yes | 23 (18.0%) | 7 (6.0%) | 30 (12.0%) |

There were 35 patients in the prehabilitation group who did not start in-hospital prehabilitation, because of various reasons including subjectively rating their condition as good (n = 13), prehabilitation program outside the hospital (n = 12), planned preoperative holiday (n = 3), no motivation to start prehabilitation (n = 3), short-term planned surgery (n = 2), prehabilitation not discussed (n = 1), and hospital admission before starting prehabilitation (n = 1) (Fig. 1). Of the patients who started in-hospital prehabilitation, 71 completed the program with at least nine in-hospital supervised exercise sessions and two consultations with a dietician (per-protocol group, baseline and operative characteristics specified in Supplement 3). Reasons not to complete prehabilitation (n = 17) were mainly because surgery was planned on short-term (n = 10). In all these cases, early surgery was the result of the hospital’s planning for the operating theater and not due to tumor-related complications. Other reasons were subjectively rated good condition (n = 2), prehabilitation too burdensome (n = 2), personal circumstances making intensive prehabilitation program unfeasible (n = 2), and holiday in between (n = 1).

No data were missing for the trial outcomes (detailed description of unweighted trial outcomes are presented in Supplement 4). Multiple imputation was applied for missing baseline characteristics, as specified in Table 1.

Propensity Scores and Overlap Weighting

There was high overlap of PS between the usual care group and the prehabilitation group, in both the intention-to-treat analysis and the per-protocol analysis (Supplement 5).

After overlap weighting, the balance of the baseline characteristics was improved between the standard care group and prehabilitation group, both on patient characteristics (e.g., age, ASA index, and MET score) and tumor characteristics (e.g., tumor localization and tumor stage) (Supplement 6).

Intention-to-Treat Analyses

There was a significant risk reduction in the occurrence of overall complications for patients in the prehabilitation group (weighted complication risk 0.45) compared with patients in the usual care group [weighted complication risk 0.69, absolute risk difference (ARD) −0.24 (95% CI −0.38 to −0.10), Table 3] and a significant risk reduction for postoperative complications [ARD −0.28 (95% CI −0.42 to −0.15)]. The number needed to treat (NNT) to reduce at least one or more overall and postoperative complication in one patient was 4.2 (95% CI 2.6–10) and 3.6 (95% CI 2.4–6.7), respectively. There was no significant difference in the occurrence of preoperative complications between the two groups [ARD 0.05 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.12), in favor of the prehabilitation group].

Table 3.

Primary weighted outcomes of the intention-to-treat population, stratified by usual care group and prehabilitation

| Weighted outcomes | Usual care (n = 128) | Prehabilitation (n = 123) | Weighted ARD | 95% CI interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complication risk | ||||

| Total | 0.69 | 0.45 | −0.24 | −0.38 to −0.10 |

| Preoperative | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.03 to 0.12 |

| Postoperative | 0.67 | 0.39 | −0.28 | −0.42 to −0.15 |

ARD absolute risk difference

Compared with patients in the usual care group, patients in the prehabilitation group had a 55% lower CCS score (95% CI −71% to −32%). The geometric mean CCS score based on overlap weighting was 3.2 in the prehabilitation group compared with 7.2 in the usual care group.

Compared with patients in the usual care group, patients in the prehabilitation group had a 33% lower length of stay [incidence rate ratio −0.33 (95% CI −0.44 to −0.18)]. The expected length of stay based on overlap weighting was 4.9 days in the prehabilitation group compared with 7.3 days in the standard care group.

There was no significant risk difference in the number of readmissions between the two groups [ARD −0.03 (95%CI −0.08 to 0.03)].

Per-Protocol Analyses

The per-protocol analysis also showed a significant risk reduction of overall complications for patients who completed prehabilitation compared with patients in the usual care group [ARD −0.21 (95% CI −0.38 to −0.04)] and a significant risk reduction for postoperative complications [ARD −0.27 (95% CI −0.44 to −0.11)]. Therefore, the NNT to prevent one extra patient from having at least one overall and one postoperative complication was 4.8 (95% CI 2.6–25) and 3.7 (95% CI 2.3–9.1), respectively. There was no significant difference in the occurrence of preoperative complications between the two groups [ARD 0.06 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.16)]. Weighted complication risks are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Primary weighted outcomes of the per-protocol population, stratified by usual care group and prehabilitation

| Weighted outcomes | Usual care (n = 128) | Prehabilitation (n = 71) | Weighted ARD | 95% CI interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complication risk | ||||

| Total | 0.73 | 0.52 | −0.21 | −0.38 to −0.04 |

| Preoperative | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.06 | −0.03 to 0.16 |

| Postoperative | 0.70 | 0.43 | −0.27 | −0.44 to −0.11 |

Compared with patients in the usual care group, patients who had completed prehabilitation had a 55% lower CCS score (95% CI −73 to 24%). Geometric mean CCS score based on overlap weighting was 3.6 in the group who completed prehabilitation compared with 8.0 in the usual care group.

Compared with patients in the usual care group, patients who completed prehabilitation had a 22% shorter length of stay; however, this was not statistically significant [incidence rate ratio −0.22 (95% CI −0.39 to −0.01)]. The expected length of stay based on overlap weighting was 5.9 days in the group who completed prehabilitation compared with 7.6 days in the standard care group.

There was no significant absolute risk difference in the number of readmissions between the two groups [ARD −0.03 (95%CI −0.08 to 0.02)].

Discussion

This is the first ETT assessing the impact of a prehabilitation intervention on perioperative complications in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery. Under the assumption that the causal model for treatment assignment was valid, the study showed that prehabilitation led to a significant risk reduction of perioperative complications. No significant difference in preoperative complications, e.g., as a result of a longer waiting time before surgery, was seen. There was a significant reduction in the number of patients who had a postoperative complication and a significant reduction in CCI scores. Furthermore, there was a significant reduction of LOS. Prehabilitation had no effect on the already limited number of readmissions.

Additional to previous RCTs that have shown evidence for the effectiveness of prehabilitation, this study provides the first preliminary evidence that prehabilitation not only improves outcomes in a controlled study setting, but also in daily clinical practice.6,10,11 Compared with previous studies showing no effect of prehabilitation, this study investigated a multimodal prehabilitation program including supervised high-intensity training.12,26–28 The concept behind combining multiple interventions, in addition to an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) program, is that of marginal gains.29–31 Although optimizing an individual aspect of care only results in a marginal gain, the aggregation effect of these marginal gains can be considerable.

The main strength of this study, compared with previous observational studies,32–34 is that the design and analyses are based on a target randomized controlled trial. Biases that often arise in observational studies, including confounding-by-indication and immortal time bias, were minimized through rigorous implementation of carefully selecting the participants based on the eligibility criteria, properly identifying the time zero, and performing both intention-to-treat and per-protocol effects. The minimization of immortal time bias is also of added value compared with previous RCTs in which patients who did not receive an operation were excluded from analysis after randomisation.11,35 In addition to patients who were potentially unfit for surgery, this study only excluded patients from the analysis that were simply not able to perform prehabilitation, such as those who were not mobile enough to participate in prehabilitation programs and those with cognitive deterioration impeding adherence to the program. Classical observational studies do not exclude or include patients with this level of rigor. This implies that observational comparisons often include patients that will never be scheduled for prehabilitation in the first place. As a result, the generalizability and transportability is increased in this study, because the study sample is more representative of patients in daily clinical practice. Moreover, the design of this study was much less resource-intensive compared with RCTs and, consequently, much more feasible in daily clinical practice. Additionally, instead of inverse probability weighting (IPW), which is often hampered by extreme propensity scores, this study used the overlap weighting (OW) method.23 Compared with IPW combined with propensity score trimming, OW produces an unbiased treatment effect estimate with lower variance and good coverage.23

There are also some limitations of the current study: (1) This is a single-center study limiting external validity. (2) The lack of random assignment may have resulted in confounded effect estimates. Although weighting was applied for all relevant baseline confounders of treatment assignment that could be measured, the findings are only internally valid if the assumed causal model for treatment assignment was correct. (3) Because a historical cohort was used for comparison, it is possible that the reduction in perioperative complications, LOS, and postoperative readmissions within 30 days after surgery was the result of better usual care over the years, rather than the effect of prehabilitation alone. However, given the relative short study period (5 years) and the previously described improvements in postoperative outcomes in the Netherlands between 2005 and 2016, it is not very likely that better usual care is the only reason for the demonstrated improvement in postoperative outcomes.4 (4) Measurement errors may have occurred because data were collected retrospectively from electronic patient records. It cannot be ruled out that identifying complications may vary somewhat over time. (5) Not including patients during or after neoadjuvant treatment may be a limitation. We excluded patients with neoadjuvant treatment in this study to reduce heterogeneity. Patients who have had neoadjuvant treatment have a different tumor pathology (locally advanced) and a different preoperative trajectory, with a longer preoperative waiting time and resilience disruption due to neoadjuvant treatment. (6) Because of the limited number of patients with ASA IV, it was not possible to draw any conclusion about the ability of a patient with ASA IV to perform high-intensity training repeatedly at least three times a week.

The methodology used in this study could be an example for further multicenter studies. However, to be able to use (large) clinical registration databases in future studies on the effect of prehabilitation and other complex interventions, these databases should incorporate more clinical predictor variables (e.g., frailty score), further specification of clinical outcomes (e.g., CCS score), and patient-reported outcome measures (e.g., quality of life).

In conclusion, this study showed a clinically relevant reduction of complications and LOS after a multimodal prehabilitation program in patients with a higher postoperative complication risk undergoing colorectal cancer surgery, compared with standard care. The study methodology may serve as an example for further larger multicenter comparative effectiveness research on prehabilitation.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgment

Grand no. 80-85009-98-1003. Zorgevaluatie Leading the Change. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Silver JK, Baima J. Cancer prehabilitation: an opportunity to decrease treatment-related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options, and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92(8):715–727. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31829b4afe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carli F, Silver JK, Feldman LS, McKee A, Gilman S, Gillis C, et al. Surgical prehabilitation in patients with cancer: state-of-the-science and recommendations for future research from a panel of subject matter experts. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2017;28(1):49–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Nes LCF, Hannink G, t Lam-Boer J, Hugen N, Verhoeven RH, de Wilt JHW. Postoperative mortality risk assessment in colorectal cancer: development and validation of a clinical prediction model using data from the Dutch ColoRectal Audit. BJS Open. 2022;6(2):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Brouwer NPM, Heil TC, Olde Rikkert MGM, Lemmens VEPP, Rutten HJT, de Wilt JHW, et al. The gap in postoperative outcome between older and younger patients with stage I-III colorectal cancer has been bridged; results from the Netherlands cancer registry. EJC. 2019;116:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santa Mina D, van Rooijen SJ, Minnella EM, Alibhai SMH, Brahmbhatt P, de Dalton SO, et al. Multiphasic prehabilitation across the cancer continuum: a narrative review and conceptual framework. Front Oncol. 2021;10:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.598425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moran J, Guinan E, McCormick P, Larkin J, Mockler D, Hussey J, et al. The ability of prehabilitation to influence postoperative outcome after intra-abdominal operation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery. 2016;160(5):1189–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau CSM, Chamberlain RS. Prehabilitation programs improve exercise capacity before and after surgery in gastrointestinal cancer surgery patients: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24(12):2829–2837. doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert JE, Hayes LD, Keegan TJ, Subar DA, Gaffney CJ. The Impact of prehabilitation on patient outcomes in hepatobiliary, colorectal, and upper gastrointestinal cancer surgery: a PRISMA-accordant meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2021;274(1):70–77. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomsen SN, Mørup ST, Mau-Sørensen M, Sillesen M, Lahart I, Christensen JF. Perioperative exercise training for patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(12):3028–3039. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2021.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillis C, Li C, Lee L, Awasthi R, Augustin B, Gamsa A, et al. Prehabilitation versus REHABILITATIONA randomized control trial in patients undergoing colorectal resection for cancer. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(5):937–947. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barberan-Garcia A, Ubre M, Roca J, Lacy AM, Burgos F, Risco R, et al. Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018;267(1):50–56. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carli F, Bousquet-Dion G, Awasthi R, Elsherbini N, Liberman S, Boutros M, et al. Effect of multimodal prehabilitation vs postoperative rehabilitation on 30-day postoperative complications for frail patients undergoing resection of colorectal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(3):233–242. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillis C, Buhler K, Bresee L, Carli F, Gramlich L, Culos-Reed N, et al. Effects of nutritional prehabilitation, with and without exercise, on outcomes of patients who undergo colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):391–410.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar A, Guss ZD, Courtney PT, Nalawade V, Sheridan P, Sarkar RR, et al. Evaluation of the use of cancer registry data for comparative effectiveness research. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2011985-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Hernán MA, Robins JM. Using big data to emulate a target trial when a randomized trial is not available. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(8):758–764. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rooijen S, Carli F, Dalton S, Thomas G, Bojesen R, Le Guen M, et al. Multimodal prehabilitation in colorectal cancer patients to improve functional capacity and reduce postoperative complications: the first international randomized controlled trial for multimodal prehabilitation. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5232-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wijnhoven HA, Schilp J, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, de Vet HC, Kruizenga HM, Deeg DJ, et al (2012) Development and validation of criteria for determining undernutrition in community-dwelling older men and women: the short nutritional assessment questionnaire 65+. Clin Nutr. 31(3):351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Bellera CA, Rainfray M, Mathoulin-Pélissier S, Mertens C, Delva F, Fonck M, et al. Screening older cancer patients: first evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(8):2166–2172. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman LS, Delaney CP, Ljungqvist O, Carli F. The SAGES/ERAS® Society manual of enhanced recovery programs for gastrointestinal surgery. New York: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jammer I, Wickboldt N, Sander M, Smith A, Schultz MJ, Pelosi P, et al. Standards for definitions and use of outcome measures for clinical effectiveness research in perioperative medicine: European Perioperative Clinical Outcome (EPCO) definitions: a statement from the ESA-ESICM joint taskforce on perioperative outcome measures. EJA. 2015;32(2):88–105. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slankamenac K, Graf R, Barkun J, Puhan MA, Clavien PA. The comprehensive complication index: a novel continuous scale to measure surgical morbidity. Ann Surg. 2013;258(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318296c732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1–67. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li F, Thomas LE, Li F. Addressing extreme propensity scores via the overlap weights. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(1):250–257. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38(6):1228–1234. doi: 10.1080/03610910902859574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34(28):3661–3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bousquet-Dion G, Awasthi R, Loiselle S, Minnella EM, Agnihotram RV, Bergdahl A, et al. Evaluation of supervised multimodal prehabilitation programme in cancer patients undergoing colorectal resection: a randomized control trial. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(6):849–859. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1423180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gloor S, Misirlic M, Frei-Lanter C, Herzog P, Müller P, Schäfli-Thurnherr J, et al. Prehabilitation in patients undergoing colorectal surgery fails to confer reduction in overall morbidity: results of a single-center, blinded, randomized controlled trial. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2022;407(3):897–907. doi: 10.1007/s00423-022-02449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fulop A, Lakatos L, Susztak N, Szijarto A, Banky B. The effect of trimodal prehabilitation on the physical and psychological health of patients undergoing colorectal surgery: a randomised clinical trial. Anaesthesia. 2021;76(1):82–90. doi: 10.1111/anae.15215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilmore DW, Kehlet H. Management of patients in fast track surgery. BMJ. 2001;322(7284):473–476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varadhan KK, Lobo DN, Ljungqvist O. Enhanced recovery after surgery: the future of improving surgical care. Crit Care Clin. 2010;26(3):527–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall D, James D, Marsden N. Marginal gains: olympic lessons in high performance for organisations. HR Bulletin Res Pract. 2012;7(2):9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Hulst HC, Bastiaannet E, Portielje JEA, van der Bol JM, Dekker JWT. Can physical prehabilitation prevent complications after colorectal cancer surgery in frail older patients? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(11):2830–2840. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2021.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mora López L, Pallisera Llovera A, Serra-Aracil X, Serra Pla S, Lucas Guerrero V, Rebasa P, et al. A single-center prospective observational study on the effect of trimodal prehabilitation in colorectal surgery. Cir Esp (Engl Ed). 2020;98(10):605–611. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2020.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Klerk M, van Dalen DH, Nahar-van Venrooij LMW, Meijerink W, Verdaasdonk EGG. A multimodal prehabilitation program in high-risk patients undergoing elective resection for colorectal cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(11):2849–2856. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2021.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berkel AEM, Bongers BC, Kotte H, Weltevreden P, de Jongh FHC, Eijsvogel MMM, et al. Effects of community-based exercise prehabilitation for patients scheduled for colorectal surgery with high risk for postoperative complications: results of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2022;275(2):e299–e306. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.