Abstract

Conservation of biodiversity is critical for the coexistence of humans and the sustenance of other living organisms within the ecosystem. Identification and prioritization of specific regions to be conserved are impossible without proper information about the sites. Advanced monitoring agencies like the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) had accredited that the sum total of species that are now threatened with extinction is higher than ever before in the past and are progressing toward extinct at an alarming rate. Besides this, the conceptualized global responses to these crises are still inadequate and entail drastic changes. Therefore, more sophisticated monitoring and conservation techniques are required which can simultaneously cover a larger surface area within a stipulated time frame and gather a large pool of data. Hence, this study is an overview of remote monitoring methods in biodiversity conservation via a survey of evidence-based reviews and related studies, wherein the description of the application of some technology for biodiversity conservation and monitoring is highlighted. Finally, the paper also describes various transformative smart technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and/or machine learning algorithms for enhanced working efficiency of currently available techniques that will aid remote monitoring methods in biodiversity conservation.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Geographic information system, Molecular techniques, Remote sensing, Wildlife conservation

Introduction

Biological diversity “biodiversity” entails the assortment of earthly life forms heterogeneously ranging from genetic to ecosystem level. It can embrace the evolutionary, ecological, and cultural aspects that uphold life in various forms (McQuatters-Gollop et al. 2019). It fosters ecological functioning that paves the path for fundamental ecosystem services comprising food, water, preservation of soil fertility, and management of pests and diseases (Avigliano et al. 2019; Whitehorn et al. 2019). The plasticity of co-existence between mankind and nature is irreversible because of the symbiotic relationship that sustains the co-survival of humans with other living organisms (Arias-Maldonado 2016).

Biological diversity of forest originating from gene to ecosystem, through species, supports forest habitat that gives rise to fodders and other goods and services in a wide array of diverse biophysical and socio-economic ambience. Despite the applicability and significance of biodiversity, its conservation is vaguely acknowledged. Presently, human invasions have distorted around 75% of the land-based territory and about 66% of the marine ecosystem. Further to this, over a third of the global terrestrial regions are now devoted to domestic pursuit (FAO 2019). Moreover, since 1970, the significance of agricultural crop yield has increased by about 300%, and harvesting of raw timber has hiked by 45%. Moreover, renewable and non-renewable resources roughly of 60 billion tons are presently extracted annually across the globe. Exploitation of land has abridged the prolificacy of 23% of the global land area, annually, up to US$577 billion in worldwide crops are in jeopardy from pollinator loss, and about 100–300 million people are at elevated threat of natural disaster due to loss of coastal habitats and protection (IPBES 2019). If such trends continue then by 2050, the transformative change in nature can lead to an unprecedented devastating irreversible impact on mankind, which will take centuries to recover.

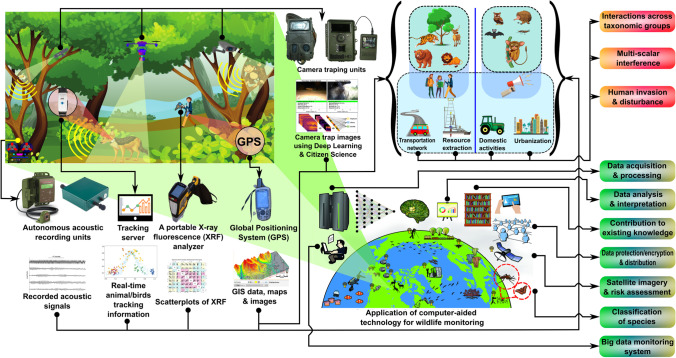

These atrocities of biodiversity need to be averted through proper monitoring and conservation measures. Based on the present advancements in technology, a combination of system-based smart techniques, remote sensing, and molecular approaches will be necessary for implementation of such ambitious conservation drives. Computer-based simulation techniques such as geographic information system (GIS), active and passive radio detection and ranging (RADAR) system, and light detection and ranging (LiDAR) system are playing a crucial role for monitoring biodiversity in real time (Bouvier et al. 2017; Bae et al. 2019; Bakx et al. 2019). Further to this, the application of recent advancements like artificial intelligence (AI) (Kwok 2019) and/or machine learning algorithms (Fernandes et al. 2020) have also been exploited for the same (Hu et al. 2015). These systems are not only reliable in monitoring biodiversity globally but can also help prevent further biodiversity loss worldwide. Besides monitoring tools, conservation of individual species and genetic biodiversity as a whole will require the use of recent molecular techniques. Conservation genomics revolves around the concept that genome-scale data will meliorate the competence of resource proprietors to conserve species. Despite the decades-long utilization of genetic approaches for conservation research, it has only recently been implied for generating genome-wide data which is functional for conservation (Supple and Shapiro 2018). The revolutionary molecular tools like restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), sequence characterized amplified region (SCAR), microsatellites and mini-satellites, expressed sequence tags (ESTs), inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR), and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have transformed the hierarchy of biodiversity conservation to a higher level (Mosa et al. 2019).

Evidently, more sophisticated monitoring methods such as system-based simulation techniques, remote sensing, artificial intelligence, and geographic information system as well as molecular-based techniques facilitate the monitoring methods in biodiversity conservation and restoration. Therefore, the present study is an overview of remote monitoring methods in biodiversity conservation via a survey of evidence-based reviews and related studies, wherein the description of the application of some technology for biodiversity conservation and monitoring. Finally, the paper also describes various transformative smart technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and/or machine learning algorithms for enhanced working efficiency of currently available techniques that will aid remote monitoring methods in biodiversity conservation.

Methodology of literature search

The relevant literature search was done electronically by using Google Search Engine, PubMed, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, Frontiers Media, and MDPI databases. The most importantly searched keywords were biodiversity and potential threats, techniques to monitoring biodiversity, geographic information system, remote sensing, active remote sensing system, radio detection and ranging (RADAR) system, light detection and ranging (LiDAR) systems, passive remote sensing systems, techniques for identification and genetic conservation of species, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), sequence characterized amplified region (SCAR), mini- and micro-satellites, expressed sequence tags (ESTs), inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR), single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and artificial intelligence in biodiversity monitoring which were used and placed repeatedly within the text.

Biodiversity and potential threats

Biodiversity in simple terms is a heterogenic distribution of flora and fauna throughout the world or in a particular niche (Naeem et al. 2016). The number of species described around the world as per IUCN (2020) accounts for 2,137,939, of which 72,327 are vertebrates, 1,501,581 are invertebrates, 422,756 are plants, and 141,275 are identified as fungi and protists. It is now acknowledged that biodiversity is a major indicator of community ecosystem fluctuations and functioning (Tilman et al. 2014). These include provisioning of food, pollination, cultural recreation, and supporting nutrient cycling (Harrison et al. 2014; Bartkowski et al. 2015). Biodiversity as a whole is represented by two major components that are species richness and species evenness. A biogeographic region with a significant level of endemic species and with a higher loss of habitat is generally depicted as a biodiversity hotspot (Marchese 2015). These areas have proven themselves as a tool for establishing conservation priorities and orchestrate vital rationale in decision-making for cost-effective tactics to safeguard biodiversity in its natural conserved state. Usually, the hotspots are marked by single or multiple species-based metrics or concentrate on phylogenetic and functional diversity to shield species that sustain exclusive and inimitable functions inside the ecosystem (Marchese 2015).

Currently, as per the IUCN Red List of Species 2020–2021, of the 2,137,939 species around the world, about 31,030 species are categorized as “threatened” species. Among these, plants with 16,460 numbers contribute the most followed by vertebrates (9063), invertebrates (5333), and fungi and protists (174) [IUCN 2020]. Many of the species are still not assessed due to a lack of reliable identification tools or techniques. Biodiversity is mostly threatened by over-population, habitat and landscape modification, indiscriminate exploitation of resources, pollution, and lack of proper documentation (Marchese 2015; Liu et al. 2020; Reid et al. 2019). Demographic changes can be considered an imperative module for assisting the indirect drivers of biodiversity alternations specifically associated with land use patterns (Newbold et al. 2015). Population explosion, central demographic developments, and urbanization impact both ecosystems and the species it harbors (Mehring et al. 2020). As the changing demographic pattern is associated with population explosion, this may pose a pessimistic impact on food availability, restricted emission of greenhouse gases, control of invasive species and diseases, etc. (Lampert 2019; Manisalidis et al. 2020; Hoban et al. 2020; Reid et al. 2019). To generate such massive data over a stipulated time frame and process them simultaneously to extrude applicable information requires cutting-edge tools and multidisciplinary scientific input (Randin et al. 2020). With recent advancements in mapping software, large-scale data processors, and monitoring tools and genetics, artificial intelligence for generating accurate data over a larger area as a part of a global monitoring strategy has now become feasible (Wetzel et al. 2015; Randin et al. 2020). Hence, an assortment of the above mention techniques and tools will be essential for the conservation and restoration of biodiversity.

Techniques for monitoring biodiversity

Mapping and monitoring techniques have been frontiers in predicting and modeling anthropogenic activities, habitat use, and pattern of land use over time in a particular region. These advanced physical techniques include GIS, LiDAR, and RADAR systems (Bouvier et al. 2017; Bae et al. 2019; Bakx et al. 2019).

Geographic information system (GIS)

Understanding functional geography and making intelligent decisions is widely beneficial for naturalists. GIS is a popular tool for analyzing possible and current spatial-temporal distribution, location, distribution patterns, population assessment, and identification of priority areas for their conservation and management (Krigas et al. 2012; Salehi and Ahmadian 2017). Currently, development of ecological niche models based on topographic, bioclimatic, soil, and land use variables was mapped and predicted for species such as Clinopodium nepeta, Thymbra capitata, Melissa officinalis, Micromeria juliana, Origanum dictamnus, O. vulgare, O. onites, Salvia fruticosa, S. pomifera, and Satureja thymbra (Bariotakis et al. 2019). With the assistance of digitally integrated video and audio-GIS (DIVA-GIS), actual geographic distribution and the future potential assortments of several Zingiber sp. like Z. mioga, Z. officinale, Z. striolatum, and Z. cochleariforme were analyzed (Huang et al. 2019). Most recently, important climatic inconsistencies distressing the geographical dispersion of wild Akebia trifoliate based on the formation of spatial database were successfully determined with the help of GIS (Wang et al. 2020). However, GIS possesses certain limitations such as expensive software, hardware, capturing GIS data, and difficulty in their use (Bearman et al. 2016) (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Application of Geographic Information Systems (GIS), remote sensing technologies like radio detection and ranging (RADAR) and satellite-based light detection and ranging (LiDAR) for wildlife monitoring in the forest ecosystem. The figure describes global forest distribution (Our World In Data 2020), wherein displayed GIS and different levels of GIS data, schismatic of passive remote sensing, active remote sensing segregated into primary RADAR system, and a block diagram of satellite-based LiDAR system for generation of DCHM (digital canopy height model) image and 3-D point cloud image of the whole organism is outlined. Global positioning system (GPS), Inertial measurement unit (IMU). The figure is inspired by the following sources: Omasa et al. (2007), Admin (2017), Bhatta and Priya (2017), Jahncke et al. (2018), Martone et al. (2018), Srivastava et al. (2020). The components of the figure are modifications of Portree (2006), Organikos (2012); Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute Smithsonian’s National Zoo (2016), and Freepik (2021). Abbreviations: FP-mode, first-pulse mode; LP-mode, last-pulse mode; DEM, digital elevation model; DTM, digital terrain model

Table 1.

Application of geographic information system (GIS) in biodiversity monitoring

| Subject investigated | Tool | Objectives | Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic information system (GIS) | ||||

| Clinopodium nepeta, Thymbra capitata, Melissa officinalis, Micromeria juliana, Origanum dictamnus, O. vulgare, O. onites, Salvia fruticosa, S. pomifera, Satureja thymbra | Geographic information system (GIS) |

• Predict and map the potential habitat • Investigate spatial patterns (niche similarities, suitability “hotspots”) • Development of database |

Ecological niche models were developed for each studied taxon, based on topographic, bioclimatic, soil, and land use variables | Bariotakis et al. (2019) |

| Zingiber mioga, Z. officinale, Z. striolatum, Z. cochleariforme, Z. kwangsiense, Z. linyunense, Z. confine, Z. kawagoii, Z. koshunensis, Z. laoticum, Z. roseum, Z. corallinum, Z. atrorubens, Z. pleiostachyum | Digitally integrated video and audio-GIS (DIVA-GIS) | • Analysis of ecological distribution and richness | Actual geographic distribution and the present and future potential distributions of Zingiber spp. | Huang et al. (2019) |

| Lippia graveolens | GIS | • Development of an analytical framework based on multi-criteria-multi objective analyses | New potential oregano harvesting areas were identified | Irina et al. (2019) |

| Panax quinquefolius | GIS | • Prediction of areas with potential ecological suitability for global medicinal plants | Ecologically suitable habitats and distribution for medicinal plant were predicted | Shen et al. (2019) |

| Brassica napus | GIS database | • Quantification of landscape composition and configuration | Landscape composition and configuration of B. napus were quantified | Reeth et al. (2019) |

| Tianzhu Mountain, National Forest Park, Fujian province, South China | GIS-analytic hierarchy process (AHP) | • Quantification and integration of the visual sensitivity and ecological sensitivity areas of the Tianzhu Mountain, National Forest Park | A comprehensive means to integrate the quantitative and objective analysis of the visual sensitivity and the ecological sensitivity was developed | Zheng et al. (2019) |

| Zea mays | GIS environment simulation | • Assessment of wildlife damage estimation methods in Z. mays with simulation in GIS environment | GIS simulations were tested as a suitable tool for testing the sampling methods in assessing wildlife damages to agriculture | Kovács et al. (2020) |

| Z. mays | GIS-AHP | • Assessment of land suitability for Z. mays farming | GIS modeling approach based on environmental and agro-ecological data was highly beneficiary for Z. mays farming and a good guide for future land-use management | Tashayo et al. (2020) |

| Ebenus armitagei, Periploca Angustifolia | GIS | Estimation of endangered plants and their distributive areas | GIS data predicted the most threatened locations, available soil dynamics, distribution, and vegetation coverage structure of the plants | Gamal et al. (2020) |

| Gentiana kurroo, Lilium polyphyllum, Saussurea costus, Aconitum chasmanthum | Global positioning system (GPS) | • To understand the distribution, ecology, and conservation implications of critically endangered endemic plants | The study revealed that the species are restricted to a small geographic range and their highly specific ecological niche makes them vulnerable to stochastic events and human interferences | Mir et al. (2020) |

| Akebia trifoliate | GIS | • Estimation of climatic variables affecting A. trifoliate growth from a macro perspective | Key climatic variables affecting the geographical distribution of wild A. trifoliate based on the establishment of spatial database were successfully determined | Wang et al. (2020) |

Remote sensing

The ability to extract information about the environment without physical contact from a large distance by a sensor that reflects and/ or emits electromagnetic spectrum (visible, infrared, and microwave spectra) is defined as remote sensing. Based on the source of radiation emitted, which comes in contact with the object, remote sensing can be categorized as active or passive remote sensing systems (Höppler et al. 2020). Remote sensing of biodiversity can be used for habitat mapping including species area curve and habitat heterogeneity, species mapping/distribution, plant functional diversity/ traits, spectral diversity including vegetation indices and spectral species (Cavender-Bares et al. 2020; Wang and Gamon 2019).

Active remote sensing system

An active remote sensor emits energy pulses and records the return time and amplitude of the backscattered energy pulses from the object to generate the required information about it (Vogeler and Cohen 2016). Currently used active remote sensing technologies like RADAR and LiDAR systems can be used to determine the location, speed, and direction of any wildlife form.

Radio detection and ranging (RADAR) system

As a sub-set of the active remote sensing system, RADAR, operates in the microwave of wavelengths of 1 mm to 1 m. Additionally, the modern RADAR systems are incorporated with software routines to mathematically enhance spatial resolution and manage multiple pictures of the same object, also as Synthetic Aperture RADARs (SARs) (Fig. 1). These systems can be used to determine the polarization of the emitted and receive electromagnetic rays which provides a better understanding of the analyzed surface properties (Hay 2000; Valbuena et al. 2020; Barlow and O’Neill 2020) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Biodiversity monitoring through remote sensing

| Subject investigated | Tool | Objectives | Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radio detection and ranging (RADAR) | ||||

| Brazilian Amazon (Manaus, Santarém, Machadinho d’Oeste) | Single-date Landsat Thematic Mapper (TM), Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS) Phased Arrayed L-band Synthetic Aperture RADAR (PALSAR) data |

• Investigation of the combined use of TM, ALOS, and PALSAR to • Discriminate mature forest, non-forest, and secondary forest • Retrieving the age of secondary forests |

The study resulted in highlighting that ASF maps can be generated without the need for extensive time-series analysis of Landsat and/or SAR data | Carreiras et al. (2017) |

| 52 least-disturbed sites along a climatic gradient between semi-arid and arid zones in the south-eastern Mediterranean | Polarimetric SAR (PolSAR) | • Determination of radar polarization and ecological pattern properties | Full polarimetric L-band PALSAR data was acquired and empirical assessments of the relationships between radar polarization properties and ecological pattern properties of climatic transition ecosystems were also acquired | Chang and Shoshany (2017) |

| Zürich | European Space Agency(ESA)-Sentinel-1A single C-band SAR, Sentinel-2A-MultiSpectral Instrument (MSI) | • Sentinel-1A SAR and Sentinel-2A MSI data fusion for urban ecosystem service mapping | Method and underlying data were effective for urban land cover and ecosystem service mapping | Haas and Ban (2017) |

| Broadleaf, needle leaf, and mixed forests in Northeastern China | ALOS/PALSAR | • Estimation of aboveground biomass | A nonlinear relationship between PALSAR backscatter coefficients and forest AGB of different forest types in NE China was constructed | Ma et al. (2017) |

| Howland Forest in Maine, Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest in Wisconsin, Harvard Forest in Massachusetts | Light detection and ranging (LiDAR) systems, ALOS/ PALSAR-horizontal transmit, and vertical receive (HV), Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) | • Modeling forest canopy height | As per the results, these techniques were potential for estimating canopy height in a different biome; furthermore, the biome-level model developed was efficient and can be used as a reliable estimator of biome-level forest structure | García et al. (2018) |

| Gran Chaco stretching across Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Brazil | Landsat-8 optical, Sentinel-1-SAR | • Mapping continuous fields of trees, shrubs, vegetation types, and savannas | Continuous fields of tree, shrub, vegetation types, and savannas covered across the entire Chaco were mapped; additionally, the relationship between tree and shrub cover and a suite of environmental and socio-economic variables were established | Baumann et al. (2018) |

| The tropical rainforests of the Western Ghats, India | Sentinel-2-MSI, SAR Sentinel-1 satellite | • Mapping and assessment of vegetation types | The magnitude of habitat fragmentation was effectively evaluated, high accuracy in classification was obtained, and vegetation indices and textures for vegetation type classification were mapped for prioritizing top conservation areas | Erinjery et al. (2018) |

| Nova Scotia |

Multi-beam RADARSAT-2 PALSAR, ALOS, and LiDAR |

• Mapping wetlands | The techniques were beneficial and generated improved wetland mapping | Jahncke et al. (2018) |

| Five villages of the Koningue commune: Dougan, Sukumba, Ngueguesso 1, Ngueguesso 2, Banesso | Sentinel-2-MSI, SRTM | • Estimation of smallholder crops production | The approach opened up new prospects for food security and agricultural performance monitoring and accuracy in smallholder farming systems | Lambert et al. (2018) |

| Tapajos National Forest | Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Advanced Land Observing Satellite 2 (JAXA’s ALOS-2), Spaceborne SAR interferometry | • Detection and quantification of selective logging events | This method has been shown to detect and quantify forest disturbance at a large scale with fine spatial resolution. It also has the potential to provide a global coverage, efficient in observing prototype of forest disturbance | Lei et al. (2018) |

| Global forest/non-forest | TerraSAR-X add-on for Digital Elevation Measurement (TanDEM-X) | • Forest/non-forest mapping | Remote sensing data represented a highly valuable source of land classification purposes, through the study identification, and monitoring of vegetated areas for agriculture, forestry, global change research, and regional planning was possible | Martone et al. (2018) |

| Rubus cuneifolius | Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 with SAR imagery | • Detection of invasive alien plant species and mapping | The technique can be used to improve discrimination and mapping | Rajah et al. (2018) |

| The state of Oklahoma, southern Great Plains, USA | ALOS/PALSAR | • Characterizing the encroachment of juniper forests into sub-humid and semi-arid prairies | Efficient analysis of the spatial dynamics of encroachment at state and county spatial scales | Wang et al. (2018) |

| Greater St. Lucia Wetland Park, South Africa |

Sentinel-1 and 2 combined with the System for Automated Geoscientific Analyses (SAGA) |

• Monitoring wetlands | An increase in overall accuracy was observed, promising ability to distinguish wetland environments, land use, and land cover classification in a location where both wetland and non-wetland classes exist was also achieved | Whyte et al. (2018) |

| Gembloux, Walloon region, Belgium | Drone-borne ground-penetrating radar (GPR) | • Soil moisture mapping | The developed tools are operational and provide consistent results in terms of spatial patterns as well as in terms of absolute soil moisture values | Wu et al. (2019a) |

| The Sahelian zone | SAR Sentinel-1 satellite, Sentinel-2-MSI | • Woody plants mapping in savannas |

High spatial resolution woody canopy map (10 m) of savanna Ecosystems were generated |

Zhang et al. 2019c) |

| Four reference sites (three located in the Amazon basin and one located in the Iberian Peninsula), 18 sites around the world (boreal forests to tropical and subtropical forests, savannas, and grasslands) |

Sentinel-1 dual-polarized backscatter images, Sentinel-2-MSI, Landsat-8 optical |

• Detection of burned area and mapping | Self-adapting to local scattering conditions, and the ability to detect burned areas during periods with no thermal anomalies were the major advantages of the technology | Belenguer-Plomer et al. (2019) |

| The eastern edge of the Tapajós National Forest region | TanDEM-X SAR interferometry | • Mapping forest successional stages | The approach showed a high performance with a low uncertainty with respect to other approaches | Bispo et al. (2019) |

| Eucalyptus forests of Western Australia | Radar Burn Ratio (RBR), SAR-based multi-temporal index, ALOS PALSAR-2 data | • Estimation of prescribed fire impacts and post-fire tree survival | The approach largely maintained the estimation accuracy of the original RBR framework while decreasing computational complexities | Fernandez-Carrillo et al. (2019) |

| Global tropical forests | ALOS-2/PALSAR-2 dual-polarization ScanSAR data | • Mapping the spatial-temporal variability of forest | Comprehensive forest variability maps for the tropics based on a homogeneous big data analysis was carried out, and the map produced were accurate and precise | Koyama et al. (2019) |

| West Kameng and Tawang districts of Arunachal Pradesh and its vicinity areas | ALOS, PALSAR, Sentinel-1A data | • Tree diversity assessment and aboveground forests biomass estimation | The study implies the potential use of the information in the reliable estimation of spatial aboveground biomass in sub-tropical to alpine forest regions | Kumar et al. (2019) |

| Gabon and Switzerland | Sentinel-2-MSI, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) | • Mapping of country-wide high-resolution vegetation height | The high spatial resolution, Sentinel-2 provides a new image every few days, which enables frequent updates, and helps to obtain good coverage even in regions with frequent clouds | Lang et al. (2019) |

| North Karelia, Białowieża, Hainich, Râsca, Colline, Metallifere, Alto Tajo, Boreal | Sentinel-2-MSI | • Assessment of variation in plant functional diversity | The technique was the potential in achieving better spatial and temporal remote sensing of the plant functional diversity | Ma et al. (2019) |

| Tanjung Karang, Sekincan, and Kuala Selangor on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia | ALOS-2 PALSAR-2 L-band, Sentinel-1 C-band SAR backscatter | • Characterizing of oil palm production landscape on tropical peat lands | Findings suggested that the technology has great potential to discriminate oil palm production landscapes managed under different management systems | Oon et al. (2019) |

| Amazon basin | DEM Multi-Error-Removed-Improved-Terrain (MERIT) based SRTM | • Mapping of inland water in tropical areas under dense vegetation | The technique provided a better sensing ability of water underneath the vegetation compared with optical sensor systems | Parrens et al. (2019) |

| Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, Teakettle Experimental Forest, La Selva Biological Station | TanDEM-X, InSAR data, simulated Global Ecosystem Dynamic Investigation (GEDI) LiDAR data | • Estimation of forest biomass | The technique yields an improved ability to map and monitor biomass globally | Qi et al. (2019) |

| Romanian forests | Sentinel-1 satellite constellation, ALOS PALSAR-2 | • Monitoring forest changes | This study exposed the strengths and shortcomings of currently available spaceborne SAR techniques and highlighted the need for developing novel processing and modeling techniques | Tanase et al. (2019) |

| Two pasture sites are located at EI Reno, central Oklahoma, USA | SAR, Sentinel-1, Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 data | • Estimation of leaf area index and aboveground biomass of grazing pastures | Improvements in capturing the phenology stages, and combined ability to monitor the seasonal dynamics of grazing pastures | Wang et al. (2019a) |

| Global forest types (tropical forest, temperate broadleaf, mixed forest, boreal forest) | ALOS, PALSAR/PALSAR-2, Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) NDVI (Normalized difference vegetation index) | • Mapping annual forest cover | The method produced an annual 25m forest maps during 2007–2016, filled the four-year gap in the ALOS and ALOS-2 time series, and enhanced the existing mapping activity | Zhang et al. (2019a, d ) |

| Thomas Fire (Dec. 2017), and Carr Fire (July 2018) in Southern California, USA |

Sentinel-1 C-band SAR sensors |

• Mapping of burnt area | The technique demonstrated better potential in highlighting burnt areas with higher accuracy | Zhang et al. (2019b) |

| Two 5 × 5-km sub-sites in northern France | SAR Sentinel-1 satellite, Sentinel-2-MSI | • Prediction of wheat and rapeseed phenological stages | Principal and secondary phenological stages of wheat and rapeseed were identified successfully | Mercier et al. (2020) |

| The St. Lucia wetlands, South Africa | SAR Sentinel-1 satellite, Sentinel-2-MSI | • Mapping and characterization of wetland | The technique yields highly accurate maps and detailed classification of the wetland | Slagter et al. (2020) |

| Combomune, Gaza Province, Southern Africa | Sentinel-2-MSI | • Monitoring intra- and inter-annual dynamics of forest degradation from charcoal production | The study showed an improvement in the spatial and temporal characterization of the main cause of forest degradation | Sedano et al. (2020) |

| Madre de Dios, a region located in southeastern Peru | MODIS NDVI, Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER), DEM | • Monitoring tropical forest degradation | Major factors associated with forest degradation were identified categorized and explored the advanced techniques | Tarazona and Miyasiro-López (2020) |

| Long-Term Socio-Ecological Research site “Pyrénées-Garonne” located in southwest France | SAR Sentinel-1 satellite, Sentinel-2-MSI | • Prediction of plant diversity in grasslands | Improved significance of prediction accuracy was obtained from Sentinel-2 data in comparison to Sentinel-1 | Fauvel et al. (2020) |

| Matang Mangrove Forest Reserve locates at west coast of Peninsular Malaysia |

Interferometric SRTM X/C-band, TanDEM-X-band |

• Structural characterization of mangrove forests | The study provided a better understanding of mangrove states and dynamics; most mangroves in the productive zones have been harvested | Lucas et al. (2020) |

| University of New England SMART Farms located near Armidale | SAR Sentinel-1 satellite, Sentinel-2-MSI | • Discrimination of species composition types | The study shows that the combination of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data can support the measurement of pasture species composition in a grazing landscape | Crabbe et al. (2020) |

| Lantana camara | Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager (OLI), Sentinel-2-MSI satellite data | • Invasive assessment of a plant species | The feasibility of using the technology for operational mapping of the invasive species and monitoring its distributional response to changes in climate, management systems, land use, and land cover | Dube et al. (2020) |

| Central Argentinian semiarid Caldén savanna biome | SRTM | • Assessment of the relationships between landscape features, soil properties, and vegetation determine ecological sites | The methodology potentially allows creation of ES maps at a regional scale and facilitates identification of threats associated with land use change, and the prescription of management strategies | Buss et al. (2020) |

| Grassland of Federal Republic of Germany | Sentinel-2 MSI, Landsat-8 OLI | • Characterization of grassland | The approach allows mapping the number and timing of mowing events in grassland at a high spatial resolution | Griffiths et al. (2020) |

| Winter wheat fields, Göttingen, Germany | SAR Sentinel-1 | • Monitoring the phenology of winter wheat | The study confirmed the use of SAR sensors to detect phenological stages of crops based on time series metrics, and to monitor crops on a regular basis | Schlund and Erasmi (2020) |

| Southern and Central China | SAR Sentinel-1 | • Monitoring of flood | The study described a reliable and efficient methodology to monitoring floods, offering continuous information on daily flood dynamics | Zeng et al. (2020) |

| Light detection and ranging (LiDAR) | ||||

| Beibu Gulf, China | LiDAR | • Determination of the post-typhoon recovery of a meso macro-tidal beach | The temporal features of the beach recovery process were reviled, erosion/accretion degrees in various beach sections were examined, and control factors of the beach recovery process were explored | Ge et al. (2017) |

| Boreal Forest and Foothills Natural Regions | Airborne LiDAR systems | • Regional mapping of vegetation structure | Three-dimensional vegetation structure was accurately measured and mapped | Guo et al. (2017) |

| The middle Heihe River Basinin Zhangye City of Gansu Province northwest China | Airborne LiDAR data, hyperspectral imagery | • Estimation of aboveground and belowground forest biomass | Results demonstrated that biomass accuracy which was improved by the use of fused LiDAR and hyperspectral data | Luo et al. (2017) |

| Evergreen and deciduous species of Mediterranean forests of Campanian forests, Telesina valley in southern Apennines of Italy | Leaf-off dedicated Airborne LiDAR data | • Detailed land use mapping, high-resolution LiDAR data, and field surveys were developed to categorize the productive and non-productive mixed forests in terms of stand attributes and structural diversity | Eight out of the ten forest types in the Campanian region were identified by high-resolution LiDAR by INFC. | Teobaldelli et al. (2017) |

| Mediterranean-type dune ecosystem in Southwest Portugal, a part of the Natura 2000 network of protected areas in the European Union. | Airborne hyperspectral imagery, LiDAR | • Detection and quantification of Gross Primary Production (GPP)-related regime shifts after Acacia invasion by mapping invader patches, accessing spatio-temporal changes during invasion, and applicability of NIRv. |

Successful mapping of high-impact invader Acacia longifolia in a heterogenous dune ecosystem. NIRv index was identified as a standardized “model metric” for quantification of high impacts of invasion even in the early stages. |

Große-Stoltenberg et al. (2018) |

| The Batang Toru tropical rain forests in the Indonesian province of North Sumatra. | LiDAR-derived Canopy Height model by Airborne Laser scanning (ALS) using LiDAR |

• Identification and characterization of forest patches based on structural attributes • Topographic attributes of the cluster by LiDAR derived Canopy Height Model |

The tallest clusters were found at significantly higher elevation (>850m) and steeper slopes (> 26°) than others, which were found to be remnants of undisturbed forests important for conservation and habitat studies along with an understanding of carbon stock. | Alexander et al. (2018) |

| Bats in four ancient semi-natural broad-leaved woodlands in Dartmoor National park situated in southwest England | Ground-based field survey with Airborne LiDAR imagery |

• Daily tracking of bats on foot-to-roost trees using various radio receivers and antennas. • Location of tree cavities using directional antennas and binoculars from the ground |

Pregnant and lactating bats switched roosts less frequently in comparison to post lactating and nulliparous bats by selecting their cavities higher on trees may be to protect their offspring from predation, | Carr et al. (2018) |

| Rainforest stands in the Central Highlands region of Southeastern Australia | Airborne LiDAR detection and ranging | • Examining the utility of complete LiDAR PAVD (plant area volume density) profiles to classify stand types in south-eastern Australia | A study demonstrated that LiDAR PAVD is used in identifying and mapping the extent of rainforest and eucalyptus stand types across a heterogenous landscape. | Fedrigo et al. (2018) |

| Tropical forest on Barro Colorado Island, Panama | LiDAR with process-based forest model FORMIND | • Comparison of 29 different LiDAR metrics by using simulated stands for their utility as predictors of tropical forest biomass at different at various spatial scales | Some LiDAR metrics like height metrics showed good correlations for forest biomass even for an undisturbed forest. | Knapp et al. (2018) |

| Bavarian forest National park in the southern- eastern part of Germany | Airborne LiDAR | • Assessing the scan angle impact on gap fraction (Pgap) and vertical Pgap profile in several forest type using different scan angles of airborne LiDAR | Discontinuous plots, Pgap, and vertical Pgap were maximum when observed from the nadir direction and rapidly decrease with increased scan angle. This indicates large off-nadir direction should be avoided to ensure a more accurate Pgap and leaf area index (LAI) estimation | Liu et al. (2018) |

| Mixed coniferous forest of Northern Sierra Nevada, California, USA | Bitemporal airborne LiDAR with field survey | • Systematic assessment of uncertainties of satellite imagery-based vegetation indices forest structural changes induced due to fuel treatment using aboveground biomass (AGB) and canopy cover as a ground reference. | Differences in vegetation indices had relatively weaker correlations to biomass changes in forest with sparse or dense biomass than in forests with moderate density before disturbance | Ma et al. (2018) |

| Set of forest structural attributes for Lidar plots located across Canada’s forest-dominated ecosystem |

LiDAR plot-derived information, Landsat pixel-based composites (large area forest attribute imputed model) |

• Demonstration of the temporal and spatial extension of imputation model using time-series of annual surface reflectance image composites with samples of airborne LiDAR • Highlighting the potential of scientific insights related to growth and recovery over large areas. |

Extension of spatial and temporal scale of the modeling framework finally demonstrated its efficacy and robustness for the entire forest of Canada over a period of three decades Built confidence in portability of their models. |

Matasci et al. (2018) |

| Subtropical intertidal wetland located to the south of Zhangjiang estuary in the southeast China | Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) camera imagery and LiDAR data | • Exploring mangrove-inundation spatial patterns |

Results indicated that >90% of mangrove forests (mainly Kandelia abovate, Avicennia marina, and Aegiceras corniculatum) were situated within a 1-m elevation range between local mean sea level and higher high water Whereas, spatial distribution showed hump-shaped patterns along the inundation gradient |

Zhu et al. (2019) |

| Three seasonal semi-deciduous natural forest cover types (OG, SGpas, and SGeuc) in the Atlantic forest biome of Southern Brazil | ALS with portable ground LiDAR remote sensing as a proxy |

• Analysis of structural attributes of forest canopies undergoing restoration. • Assessing ability of the attributes to distinguish forest cover types to estimate aboveground woody biomass (AGB) |

A set of six canopy structure attributes were able to classify five cover types with an overall accuracy of 75% AGB was well predicted by canopy height and unprecedented “leaf area height volume” |

Almeida et al. (2019) |

| A widely distributed bamboo species Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens) in the subtropical forests of south China | Airborne LiDAR with Principal component analysis (PCA) | • Assessing estimation of canopy structure and biomass of Moso bamboo by PCA | The result showed LiDAR well predicted the AGB of Moso bamboo with the percentile heights and coefficient of variation of height (hcv) having the highest relative importance for estimating AGB and culm biomass | Cao et al. (2019) |

| An area characterized by uneven-aged mixed species forest called Lavarone (Trento) in the Italian Alps | Airborne LiDAR |

• Mapping fine-scale variation in aboveground carbon density (ACD) and its change over time across the landscape • Linking the changes in ACD to forest structural attributes, species composition, disturbance regime, and local topography |

Results indicated between 2007 and 2011 the majority of landscapes (61%) increased in ACD with a much smaller fraction of study areas exhibiting evidence of small-scale natural disturbances (3.7%) | Dalponte et al. (2019) |

| Two European forest types; a coniferous mountain forest in the Eastern Italian Alps and a mixed temperate forest in southern Germany | LiDAR with spectral variation hypothesis (SVH) | • Height variation hypothesis (HVH) is a concept of linking height heterogeneity (HH) of a forest and its tree diversity using the heterogeneity index Rao’s Q by Canopy Height Model (CHM) | HH was highly correlated to tree species diversity of the forest ecosystem in coniferous mountain forests than in mixed temperate forests when calculated with CHM resolution 2.5 m | Torresani et al. (2020) |

| Insects flying over Ostra Herrestad wind farm near the town Shimrishamn in southernmost Sweden | High resolution Scheimflug lidar | • Testing feasibility of a high resolution of a vertical Scheimflug lidar to resolve a small target over a wind farm independently of sunlight to test insect hypothesis | Insect swarms appeared at short intervals and varied in their time of formation, dispersal, density, and size of swarming; which was sometimes according to emergence time of bats | Jansson et al. (2020) |

| Municipalities of Nova Ubirita and Feliz Natal, Matto Grosso near the southern extent of closed-canopy forests in the Brazilian Amazon | Acoustic Space Occupancy Model with ecoacoustic and Airborne LiDAR data | • Evaluating the role of forest structure in explaining variability in acoustic community assembly by illustrating and investigating hypothesized synergies between 3D observations of acoustic space-filling and physical space filling | The findings underscore the important synergies between lidar and ecoacoustics for informing models of occupancy and detection and supporting future investigations towards the role of habitat structure in shaping habitat use | Rappaport et al. (2020) |

| Inner Mongolia autonomous region of China | ICESat-2 data, airborne LiDAR data |

• Develop a machine learning workflow for mapping the spatial pattern of the forest canopy height (Hcanopy) foot print products from ICES-2 and Sentinel satellite data. • Its validation by high-resolution canopy height from airborne LiDAR at different spatial scales • Performance comparison between two machine learning models (DL and RF), and between Sentinel, and LANDSAT satellites. |

Results revealed the reliability of ICES-2 vegetation height products as ICES-2 Hcanopy showed to have the highest correlation with airborne LiDAR canopy height at a spatial scale Performance comparison of DL and RF model revealed satisfactory accuracy on the up-scaling of ICES-2 Hcanopy |

Li et al. (2020b) |

| The Bialoweiza Forest UNESCO world heritage site of European forest | Hyperspectral and LiDAR data | • Derivation of information on tree species dominance and aboveground biomass in the forest by testing and evaluating hyperspectral and LiDAR data |

Outcomes showed vegetation indices from hyperspectral data can support species dominance detection. Accuracy of the level of species dominance in the forest plots varied when tested using the Multivariate Multiple Linear Regression model |

Laurin et al. (2020) |

| Six sites located across Canada cover a wide range of forest types, terrain conditions, species composition, stand structural characteristics, and disturbance regimes. | Landsat time series data, airborne laser scanning (ALS) LiDAR | • Investigation of accuracy of spectral indices and time series lengths for estimates of forest attributes as stand height, basal area, and stem volume across a range of conditions by ALS calibration |

An improvement in estimation accuracy in the six sites was seen with an increase in time series length Model accuracies plateaued at a time series length of 15 years for two sites |

Bolton et al. (2020) |

| Four spoil heaps originating from brown coal mining located in the north Bohemian Brown coal basin in the Czech Republic of Europe | Hyperspectral data, LiDAR data, and integrated approaches of both | • Comparing various approaches (hyperspectral data, LiDAR data, and integrative approach) in the extraction of open surface water bodies on spoil heaps from very high-resolution airborne data (<2 m) |

Individual approaches resulted in 2–22.4% underestimation of the water surface area and 0.4–1.8 % overestimation. The integrative approach improved discrimination over all other approaches |

Prošek et al. (2020) |

| Five forest types, where four forest study sites were part of the ForestGEO megaplot network (Moist lowland rainforest at Barro Colorado Island (BCI) in Panama of Central America, Rabi, Gabon a Central African lowland rainforest, SERC plot of USA, and Traunstein in Germany) and the fifth site was lowland tropical rainforest of Paracou at French Guiana in South America | Airborne discrete return LiDAR data | • Quantification of different aspects of forest structure, i.e., mean canopy height, maximum canopy height, stand density, vertical heterogeneity, and wood density different for each discretion. | Biomass predictions using the best general model were found to be almost as accurate as predictions using five site-specific models. | Knapp et al. (2020) |

There are two basic types of RADAR systems, namely, primary and secondary. In the primary system, the signal is transmitted in all directions however some of the signals are reflected back to the receiver after colliding with the target thereby defining or detecting the location of the target (Hirst 2008; Bhatta and Priya 2017). In this system, the transmitted signal needs to be of high power to ensure that the reflected signal is sufficient enough to provide accurate and precise information about the target (Bhatta and Priya 2017). Again, noise and signal attenuation due to some factors might disrupt the reflected signal which can also be regarded as a limitation (Bhatta and Priya 2017; Martone et al. 2018). In the secondary RADAR system, an active answering signal system has been installed for accuracy, where the transmitted signal is received by a compatible transponder that retrieves the signal and further sends a signal comprising the useful information in a coded form (Hirst 2008; Bhatta and Priya 2017). The receiver receives the coded signal, and after decryption of the code, the information about the target is transcribed, thereby providing information about the real-time spatial orientation (Bhatta and Priya 2017; Jahncke et al. 2018).

Further to this, ultra wideband (UWB) RADAR is one of the traditional methods used for life detection that analyzes the reflected/echo signal received after hitting the target. Micro-motions by humans, nearby environment, and clutter signals can modulate the reflected signal. As per evidence, it is a reasonable, effective, and complete non-invasive life detection method (Chunming and Guoliang 2012; Karthikeyan and Preethi 2018; Yin and Zhou 2019). With the growth of scientific innovation in the field of remote sensing, a hybrid (On-Chip Split-Ring-Based Sensor) RADAR system has emerged with high-resolution range and sensitivity. This system can easily detect multiple life forms simultaneously even across obstacles (Liu et al. 2016).

One of the major applications of RADAR is range detection and to date, the replacement of the sensing and detection efficiency and accuracy by RADAR has not been possible by any other electronic system (Bhatta and Priya 2017; Parrens et al. 2019). Extension of the sensing capability with respect to atmospheric conditions such as rain, snow, smoke, darkness, and fog and collecting the data makes it unexceptional and advantageous. At present, RADARs have broad areas of applications in defense and control systems, monitoring and forecast systems, astronomy, target-locating system and remote sensing, etc. (Bhatta and Priya 2017).

Light detection and ranging (LiDAR) systems

LiDAR is a widely recognized technology, especially the airborne laser scanner (ALS), which focuses on the emission and receipt of laser pulses. During field surveys, LiDAR technology offers the potential to establish variables, representing forest structures that are distinct from those detected or assessed. Bitemporal airborne LiDAR with field survey is widely used for systematic assessment of uncertainties in satellite imagery-based vegetation (Ma et al. 2018). Ground-based field survey with airborne LiDAR is applicable for daily tracking of bats on foot-to-roost trees using various radio receivers and antennas and the location of tree cavities using directional antennas and binoculars from the ground (Carr et al. 2018; Stephenson 2020) (Fig. 1, Table 2).

Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) camera with LiDAR data is used for surveying mangrove-inundation spatial patterns in a subtropical intertidal wetland in southeast China (Zhu et al. 2019). With the support of artificial intelligence (AI), LiDAR remote sensing is found to be successful in predicting models for efficient biodiversity study by covering more areas with a clear database in a very span of time. LiDAR plot extracted information and Landsat pixel-based composites along with time-series were effective in modeling sets of reflectance images of forest structure across Canada’s forest-dominated ecosystem (Matasci et al. 2018). More advanced LiDAR technologies have now overtaken the previous ones in terms of both efficacy and accuracy. Almeida et al. (2019) in their research on three seasonal semi-deciduous natural forest cover types in the Atlantic forest biome of Southern Brazil have considered ALS with portable ground LiDAR remote sensing as a proxy for analysis of structural hallmarks of forest canopies enduring restoration. Airborne LiDAR with principal component analysis (PCA) assessed the estimation of canopy structure and biomass of Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens) in widely distributed subtropical forests of south China (Cao et al. 2019). High-resolution vertical Scheimpflug LiDAR has proven to resolve hypothesis for insects flying over Ostra Herrestad wind farm near the town Shimrishamn in southern Sweden (Jansson et al. 2020).

To conserve plant diversity information on various forest attributes, aboveground biomass (AGB), canopy structure, canopy cover, and leaf area index (LAI) are considered important and can be assessed most efficiently with a technique like LiDAR (Bolton et al. 2020). Forest canopy height could be an important indicator of biodiversity, productivity, and carbon storage (Li et al. 2020b). LiDAR when combined with other RS techniques, i.e., high spatial resolution with hyperspectral sensors, thermal remote sensing, and satellite RS are yielding eye-catching results, particularly in biodiversity and ecosystem conservation.

Passive remote sensing systems

Passive remote sensing is often understood as a system that operates by passive sensors which can only be used for detection in presence of the natural source of energy, i.e., sunlight (visible to shortwave spectrum and infrared thermal radiation) (Srivastava et al. 2020). These sensors have a specialty to detect natural energy (radiation) that is either emitted or reflected from the source of energy or object (Earthdata 2021). Limitations of the applicability of passive remote sensing for biodiversity and ecosystem conservation are its dependency on sunlight as a source of radiation which is again dependent completely on the season, region, and climatic conditions (Fig. 1).

Techniques for identification and genetic conservation of species

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)

RFLP is a biallelic, polymorphic genetic marker characterized by hybrid labeled probes of DNA fragments and digested with restriction endonucleases for estimations of genetic diversity (Vignal et al. 2002; Amom and Nongdam 2017). Different restriction sites in DNA represent the genetic divergence between different populations or related species within a population. Özdil et al. (2018) demonstrated genetic diversity among 11 donkey species in Turkey by conducting PCR-RFLP of two genes. The restriction sites of DraII, MboI, and EagI on the lactoferrin gene (LTF) and PstI on the κ-casein gene (CSN3) have been validated to identify the polymorphism among the donkey population (Özdil et al. 2018). Meikasari et al. (2019) have also made elucidation of low genetic diversity among the seahorse (Hippocampus comes) found in Bintan waters. Another recent study indicates the utilization of PCR-RFLP in genetic-based sex determination of Sebastes rockfish (Vaux et al. 2020). The PCR-RFLP application in identification of durum (Triticum durum L.) and bread wheat (T. aestivum) species has also been studied by analyzing chloroplast DNA (Haider and Nabulsi 2020) (Table 3, Fig. 2A).

Table 3.

Molecular and Genomic techniques used for conservation of biodiversity

| Technique | Species | Purpose | Output | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | ||||

| Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) | Japanese Rana | Rana japonica, R. ornativentris, R. tagoitagoi | Species identification | Successful in detecting Rana species in static water in both laboratory and field | Igawa et al. (2019) |

| Turkish donkey | Equus asinus | Genetic diversity of κ-casein (CSN3) and lactoferrin (LTF) genes | Novel single nucleotide polymorphism has been firstly detected in the LTF gene with the EagI restriction enzyme | Özdil et al. (2019) | |

| Seahorse | Hippocampus comes | Identification of allelic diversity | Genetic diversity of the population of seahorse species of H. comes was low | Meikasari et al. (2019) | |

| Cattle breeds | - | Assessment of the genetic structure based on functional gene polymorphism | Gene flow, little variation, and genetic isolation were observed due to close geographic proximity | Kasprzak-Filipek et al. (2019) | |

| White River beardtongue | Penstemon scariosus | Genetic diversity and differentiation patterns analysis | Most of the genetic variation is within populations and high proportion of the genetic variation is due to geographic distance | Rodríguez-Peña et al. (2018) | |

| Pau-branco | Picconia azorica | Genetic diversity and biotaxonomy analysis | Monophyly of Picconia and low genetic diversity and a weak genetic structure | Ferreira et al. (2011) | |

| Durum and bread wheat | Triticum durum L., and T. aestivum L. | Species identification | Provided sufficient variation for the identification | Haider and Nabulsi (2020) | |

| Brown trout | Salmo trutta | Genetic structure analysis | Showed a high percentage of allochthonous genes among the individuals | Molerović et al. (2019) | |

| Sebastes rockfish | Sebastes melanops, S. mystinus, S. pinniger, S. diaconus, S. entomelas, and S. flavidus | Sex identification | Indicated that the association of this restriction site with sex is species-dependent | Vaux et al. (2020) | |

| Egyptian Origanum and Thymus | Origanum vulgare, Origanumsyriacum (L.) subsp. sinaicum, Thymus vulgaris, T. capitatus L., and T. decassatus | Genetic diversity analysis | Elucidate the genetic variations and phylogenetic relationships within the studied species | El-Demerdash et al. (2019) | |

| Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) | Guazuma | Guazuma crinita | Genetic diversity analysis | Showed higher genetic diversity | Tuisima-Coral et al. (2020) |

| Ornamental onion | Allium stipitatum | Genetic characterization | High genetic diversity occurred among the population | Ebrahimi et al. (2019) | |

| Himalayan bitter gourd | Herpetospermum caudigerum | Genetic diversity and genetic structure analysis | Showed rich genetic diversities and greater genetic differentiation among populations | Xu et al. (2019) | |

| Wildrye | Elymus tangutorum | Genetic diversity and genetic structure analysis | A significant correlation between genetic and geographical distance was observed, also the significant ecological influence of average annual precipitation on genetic distance was revealed | Wu et al. (2019b) | |

| Noble crayfish | Astacus astacus L. | Genetic diversity analysis | Significant genetic diversity was revealed | Panicz et al. (2019) | |

| Anomura | Aegla georginae, A. ludwigi, and A. platensis | Genetic diversity analysis | Showed low levels of genetic diversity | Zimmermann et al. (2019) | |

| Freshwater snail | Melanopsis etrusca | Genetic diversity analysis | Showed two or perhaps three clusters of populations and there probably is some connectivity among populations in close geographic proximity | Neiber et al. (2020) | |

| Muga silkworm | Antherae aassamensis | Phylogeny and Genetic diversity analysis | Wide range of genetic distance was observed and sequences comprised of two major clade | Saikia et al. (2019) | |

| Random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) | Wormwood | Artemisia judaica | Genetic diversity analysis | Presence of genetic variation | Al-Rawashdeh (2011) |

| Pa Co pine | Pinus kwangtungensis | Analysis of genetic diversity | High genetic variation was found | Thuy et al. (2020) | |

| Jongly Ada | Alpinia nigra | Genetic diversity analysis | Lower amount of gene flow was observed | Basak et al. (2019) | |

| white garland-lily | Hedychium coronarium | Population genetic structure and diversity analysis | High genetic diversity occurred among the population and showed similar grouping patterns | Ray et al. (2019) | |

| Old World tree frogs | Rhacophorus margaritifer | Genetic diversity analysis | Showed high genetic diversity and high locus variation | Sulistyahadi et al. (2020) | |

| Awassi sheep | - | Genetic polymorphism and diversity analysis | The study revealed substantial divergence among populations and displayed a remarkable degree of consistency between geographic origins, breeding histories, and the pattern of genetic differentiation | Al-Allak et al. (2020) | |

| Eri silkworm | Philosamia ricini | Genetic diversity analysis | revealed a low genetic diversity among the morphs | Saikia and Devi (2019) | |

| Banapsha | Viola serpens | Species identification | Revealed successful identification of the genuine samples | Jha et al. (2020) | |

| Sequence characterized amplified region (SCAR) | Oriental penthorum | Penthorumchinense | Genetic identification and authentication | Enabled reliable genetic identification | Mei et al. (2017) |

| - | Morusboninensis and Morusacidosa | Development of SCAR markers | All hybrid seedlings identified according to the molecular markers | Tani et al. (2003) | |

| Anglojap yew | Taxus media | Development of SCAR markers | Turned out to be a quick, efficient, and reliable tool for identification | Hao et al. (2018) | |

| Japanese honeysuckle | Lonicera japonica | Development of SCAR markers | Found as an efficient molecular marker to study the genetic variation of any organism | Yang et al. (2014) | |

| Okinawa Agu pigs | - | Evaluation of the genetic structure | Revealed a substantial loss of genetic diversity among Agu pigs due to inbreeding | Touma et al. (2019) | |

| Micro-satellites and mini-satellites | Robusta coffee | Coffeaca nephora | Genetic diversity and population structure analysis | Detected population genetic structure with distinct geographic distribution | Labouisse et al. (2020) |

| White-lipped peccaries | Tayassu pecari | Genetic diversity and population structure analysis | Detected a similar levels of genetic diversity in all localities and a pattern of isolation by distance | de Góes Maciel et al. (2019) | |

| Vilca | Anadenanthera colubrina | Demographic history and spatial genetic structure analysis | Revealed an ancient population expansion and found high levels of genetic diversity and high inbreeding | Goncalves et al. (2019) | |

| Fragrant rosewood | Dalbergia odorifera | Genetic diversity and population structure analysis | Medium genetic diversity level was inferred and genetic variation existed among populations | Liu et al. (2019a) | |

| Mediterranean swordfish | Xiphias gladius | Genetic diversity and population structure analysis | Revealed the presence of three genetic clusters and a high level of admixture within the Mediterranean Sea | Righi et al. (2020) | |

| Marsh orchid | Dactylorhiza majalis | Genetic diversity analysis | Showed a moderate level of genetic diversity and a significant correlation between the morphological and genetic distance matrices | Naczk and Ziętara (2019) | |

| Central American river turtle | Dermatemys mawii | Genetic diversity and population structure analysis | Showed significantly higher genetic diversity and highest genetic differentiation in wild population | Gallardo-Alvárez et al. (2019) | |

| Turkish sheep breeds | - | Genetic diversity and differentiation analysis | Showed some populations still hold enough genetic diversity despite decreasing in population sizes in the last few decades | Karsli et al. (2020) | |

| Iron walnut | Juglans regia | Population genetic structure and adaptive differentiation analysis | Revealed relatively low genetic diversity, high interpopulation genetic differentiation, and asymmetric interpopulation gene flow | Sun et al. (2019) | |

| Expressed sequence tags (ESTs) | Liquorice | Glycyrrhiza glabra L | Genetic structure and variation analysis | Variability was related to the intra-population level | Esmaeili et al. (2020) |

| Asunaro | Thujopsisdolabrata | Phylogeographic and genetic population relationships | Exhibited relatively uniform genetic diversity and found a significant and relatively high value of overall population differentiation among the populations | Inanaga et al. (2020) | |

| - | Magnolia patungensis | Genetic diversity analysis | Significant genetic differentiation and low gene flow among populations were discovered | Wagutu et al. (2020) | |

| Pearly everlasting | Anaphalis spp. | Genetic diversity analysis | Genetic diversity has a fairly low value that occurs within and between populations | Ade et al. (2019) | |

| Star magnolia | Magnolia sinostellata | Genetic diversity and population structure | Showed rich genetic diversity and serious genetic drift occurred within populations. Also, genetic differentiation is apparent among the populations | Wang et al. (2019b) | |

| Ironwood | Parrotia subaequalis | Genetic diversity analysis | A relatively high level of genetic diversity and genetic differentiation level was detected. Additionally, a high level of cross-transferability was displayed | Zhang et al. (2019e) | |

| Shrubby horsetail | Ephedra foliata | Analysis of genetic diversity and population genetic structure | Revealed higher levels of polymorphism, diversity index, and effective multiplex ratio | Meena et al. (2019) | |

| Inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR) | Zarrin-Giah | Dracocephalumkotschyi | Genetic diversity analysis | Revealed a broad genetic variation among the populations | Sereshkeh et al. (2019) |

| Bergenia | Bergenia ciliata | Genetic diversity analysis | Revealed highest percentage of variation and low genetic diversity within populations | Tiwari et al. (2020) | |

| Peony | Paeonia decomposita | Analysis of genetic diversity and population genetic structure | Revealed moderate genetic diversity and a significant positive correlation between geographic and genetic distance among populations | Wang et al. (2020) | |

| Thunb | Huperzia serrata | Analysis of genetic diversity and variation | Genetic diversity was relatively high at population and species level | Minh et al. (2019) | |

| New Zealand white rabbit | Oryctolagus cuniculus | Genetic diversity analysis | No significant differences in the genetic diversity | Li et al. (2020a) | |

| Tunisian local cattle | - | Genetic diversity analysis | Genetic diversity was relatively high at population and species level | El Hentati et al. (2019) | |

| Korean-native Jeju horse | Equus caballus | Comprehensive genome and transcriptome analyses | Help in designing high-density SNP chip for studying other native horse breeds | Srikanth et al. (2019) | |

| Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) | Wildcats and domestic cats | - | To assess hybridization between wildcat and domestic cat populations | Showed a complete genetic continuum or hybrid swarm structure | Senn et al. (2019) |

| Lion | Panthera leo | Spatiotemporal genetic diversity | Gene flow and local subpopulations due to habitat fragmentation | Curry et al. (2021) | |

| Italian chicken breeds | - | Genetic diversity and population structure analysis | Showed most breeds formed non-overlapping clusters and were clearly separate populations, which indicated the presence of gene flow | Cendron et al. (2020) | |

| Ethiopian durum wheat | Triticum turgidum ssp. durum | Genetic diversity and population structure analysis | Showed higher genetic diversity and higher genetic admixture between landraces despite their geographic origin | Alemu et al. (2020) | |

| Dragonhead | Dracocephalumruy schiana | Genetic diversity and differentiation | Showed structuring and differentiation between populations | Kyrkjeeide et al. (2020) | |

| Star swertia | Swertia mussotii | Genetic differentiation | Showed genetic differentiations often occurred in genes known to be involved in various metabolic processes and revealed a significant positive correlation between the genetic similarity and geographical distance | Qiao et al. (2021) | |

| Tasmanian devil | Sarcophilus harrisii | Genetic diversity and population structure | Low genetic diversity within population was observed | Miller et al. (2011) | |

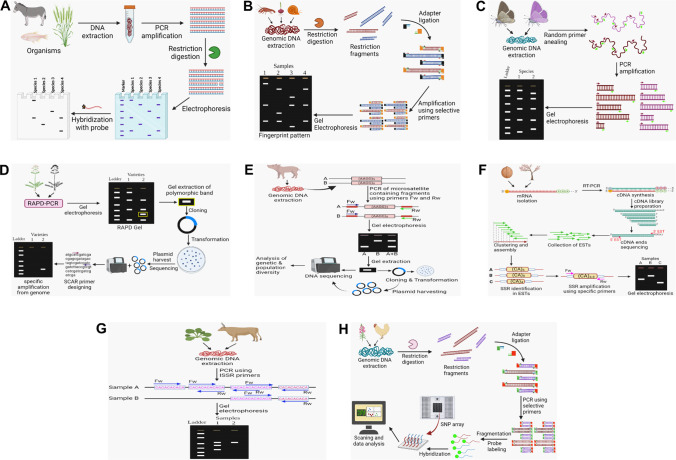

Fig. 2.

Molecular techniques for conservation of biodiversity. A Restriction fragment length polymorphism; the genomic DNA extracted from different organisms is PCR amplified and subjected to restriction digestion using specific restriction enzymes, then DNA fragments are separated by electrophoresis and hybridized with radiolabeled probes (Özdil et al. 2018; Chaudhary and Maurya 2019; Panigrahi et al. 2019; Haider and Nabulsi 2020). B Amplified fragment length polymorphism; the restriction fragments of genomic DNA was ligated with compatible adapters and PCR amplified using selective primers against adapters, and the amplified fragments were separated by electrophoresis for DNA fingerprint analysis (Blears et al. 1998; Malik et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2019b; Zimmermann et al. 2019; Neiber et al. 2020). C Random amplified polymorphic DNA; random PCR fragments were amplified from the genome of different species using primers with random sequences and separated by gel electrophoresis to determine the difference between species based on RAPD markers (Panigrahi et al. 2019; Saikia et al. 2019). D Sequence characterized amplified region; PCR products are generated using primers for RAPD markers from the genome of different varieties and separated in the gel. The polymorphic DNA band is gel extracted and processed for cloning and sequencing for getting specific amplification by designing SCAR primers (Yang et al. 2014; Bhagyawant 2015; Ganie et al. 2015; Cunha and Domingues 2017). E Micro-satellites; the microsatellite repeats were PCR amplified using primers that flank the repeated sequence and separated by gel electrophoresis. The individual bands were cloned and sequenced for analysis of genetic and population diversity (Kim 2019; Touma et al. 2019). F Expressed sequence tag-simple sequence repeat; cDNA library was prepared from cDNA synthesized from isolated mRNAs, and then end sequencing of cDNA library was performed by EST primers followed by its assembly. The SSR regions were amplified in assembled ESTs using specific primers and the products were analyzed in gel (Rudd 2003; Sun et al. 2019; Wagutu et al. 2020). G Inter-simple sequence repeat; the isolated genomic DNA from organisms was subjected to PCR amplification using primers specific to microsatellite, and the PCR products were separated by electrophoresis for analysis (Sarwat 2012; El Hentati et al. 2019; Tiwari et al. 2020). H Single nucleotide polymorphism; the genomic DNA from different samples was digested with suitable restriction enzyme followed by adapter ligation and PCR amplification using selective primers. Further to this, PCR products were fragmented with DNase I and labeled with fluorescent probes followed by hybridization in an SNP array. The wells were scanned and data were analyzed (Alsolami et al. 2013; Scionti et al. 2018; Cendron et al. 2020; Kyrkjeeide et al. 2020)

Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP)

AFLP is considered an effective means of detecting polymorphism in DNA without having any prior information regarding the genome. Being a dominant marker, it can analyze multiple loci through amplification of DNA performing PCR reaction (Bryan et al. 2017). The method employs restriction digestion of DNA and amplification of fragments through ligation of adapters on both ends and using primers specific to adapters (Malik et al. 2018). Genetic differences can be identified from the disparity in the number and length of bands on electrophoretic separation. Its application ranges from the assessment of genetic diversity within species to generate of genetic maps for disease diagnosis and phylogenetic studies. AFLP data analysis study represents the genetic diversity in E. tangutorum population contributed by geographical and environmental factors (Wu et al. 2019b). The phylogenetic relationships and genetic distances among A. platensis populations and other distinct related species such as A. georginae and A. ludwigi in southern Brazil were also investigated through AFLP (Zimmermann et al. 2019). Population structure and differentiation among Melanopsis etrusca were clearly distinct between the eastern, western, and central regions populations in Italy (Neiber et al. 2020) (Table 3, Fig. 2B).

Random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD)

The RAPD is a PCR-based technique in which 8–10 short nucleotides comprise both forward and reverse primers that bind arbitrary nucleotide sequences of chromosomal DNA to generate random fragments. Due to this random nature of primers, no prior knowledge about genome sequence is needed. The annealing sites of these random primers vary for different species or individual to individual. Discrimination can be identified or determined from the amplified DNA fragments (RAPD markers) separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (Freigoun et al. 2020). RAPD markers are dominant and involved in various applications such as genome mapping, molecular evolutionary genetics, genetic diversity analysis, and population genetics as well as determining taxonomic identity (Qamer et al. 2021). Saikia et al. (2019) deduced genetic variation among the different morphs of muga silkworm of Northeast India through RAPD analysis. Moreover, Sulistyahadi et al. (2020) studied the locus diversity as well as genetic polymorphism of the endemic species Rhacophorus margaritifer population by this technique. It has also been used to elucidate the genetic variation in a medicinal plant species found in the south of Jordan named Artemisia judaica (Al-Rawashdeh 2011) (Table 3, Fig. 2C).

Sequence characterized amplified region (SCAR)

SCAR markers are DNA fragments generated by PCR amplification using specific 15–30-bp long primers derived from RAPD markers through cloning and sequencing (Bhagyawant 2015). Usually, RAPD markers are associated with low reproducibility and are dominant in nature, making it inappropriate for species identification (Sairkar et al. 2016). To overcome this disadvantage, RAPD markers are converted to SCAR markers which are locus-specific and co-dominant in nature (Bhagyawant 2015; Feng et al. 2018). Due to the specificity of primers, PCR amplification of SCARs is less sensitive to reaction condition and thus are easy to perform (Yuskianti and Shiraishi 2010). SCAR markers provide authenticate information both for species identification and population genetic diversity analysis. Researchers have successfully developed SCAR markers for the medicinal plant V. serpens using 1135-bp long amplicon through RAPD obtained by six accessions of the plant, thereby preventing it from extinction (Jha et al. 2020) (Table 3, Fig. 2D).

Mini- and micro-satellites

Mini-satellites (variable number of tandem repeats (VNTRs) 6–100 bp) and micro-satellites (1–6 bp) (simple sequence repeats (SSR) and short tandem repeats (STR)) are randomly repetitive DNA sequences widely dispersed in all eukaryotic species genomes. These multi-allelic markers are co-dominantly inherited with species-specific location and size within the genome (Vergnaud and Denoeud 2000; Vieira et al. 2016). Due to the high level of polymorphism associated with mini and microsatellites, it is extensively utilized in genetic analysis and population studies. Microsatellites are interspersed all over the genome and therefore represent high variability and their identification show great variation among species of the different population (Abdul-Muneer 2014). Its analysis includes PCR amplification of loci by using primers that flank the repeated sequence. By using microsatellite markers, genetic structure of Agu pigs has been elucidated along with its correlation with Ryukyu wild boar, two Chinese breeds and five European breeds (Touma et al. 2019). Similarly, De Góes Maciel et al. (2019) analyzed 13 microsatellite loci of 361 white-lipped peccaries for assessment of their population structure and level of genetic diversity (Table 3, Fig. 2E).

Expressed sequence tags (ESTs)

ESTs are small sequences of DNA usually 200 to 500 nucleotides long that act as tags for the expressed genes in certain cells, tissues, or organs. ESTs are generated by sequencing either the 3′ end or 5′ end of a segment derived from random clones from the cDNA library and long enough for the identity illustration of the expressed gene (Behera et al. 2013). ESTs are widely involved in gene discovery, determining the phylogenetic relationship between individuals, genetic diversity, and proteomic analysis as well as transcriptome profiling (Cai et al. 2015). EST-derived SSR markers are more informative than genomic SSRs for genetic diversity analysis due to several advantages such as high conserved nature, variation in coding sequence, and high heritability to closely related species (Parthiban et al. 2018). Sun et al. (2019) have conducted the structure analyses of expressed sequence tag-simple sequence repeat (EST-SSR) markers in Juglans sigillata and demonstrated the genetic structure based on its geographic feature. Moreover, EST-SSR analyses have provided information regarding the genetic distance between the J. regia and J. sigillata populations. By considering EST-SSRs and genotype sequencing data, they have interpreted iron walnut as the subspecies of J. regia (Sun et al. 2019). Investigation of evolutionary relations and genotypic relatedness are essential for the conservation of endangered species. Recently the genetic variability of an endangered species Magnolia patungensis was studied by analyzing the EST-SSR polymorphic markers (Wagutu et al. 2020) (Table 3, Fig. 2F).

Inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR)

ISSR markers are used in diversified analyses such as species identification, evolutionary and taxonomic studies, genome mapping, genetic diversity, and gene tagging because of their high polymorphic nature (Arif et al. 2011; Abdelaziz et al. 2020). These multilocus markers are generated through PCR amplification by using microsatellites as primers. Prior sequence knowledge is not required for primer designing as repeat sequence is used to amplify these inter-microsatellite regions (Ng and Tan 2015). It overcomes all the limitations possessed by other markers such as RAPD and AFLP which are associated with low reproducibility (Najafzadeh et al. 2014). Genetic diversity and population structure analysis have been performed among 11 populations of Bergenia ciliata using 15 ISSR markers. The analysis shows a high level of polymorphism among this medicinal plant species, found in the Indian Himalayan Region (Tiwari et al. 2020). El Hentati et al. (2019) have studied genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships among 20 samples of three geographical local cattle populations using ISSR primers. They found a significant variation and geographical separation among the cattle from the north, northeast, and northwest of Tunisia (Table 3, Fig. 2G).

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)