On July 23, 2022, WHO declared that the 2022 monkeypox outbreak was a public health emergency of international concern.1 To date, the most commonly described mechanism of viral transmission in this outbreak is close contact in the context of high-risk sexual behaviour, mainly between men who have sex with men.2, 3

The monkeypox virus belongs to the orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family, which is known to have long-lasting stability in the environment. Samples from individuals with monkeypox virus (eg, dermal crusts) and from contaminated fomites can remain infectious for an extended period of time.4, 5

On July 19, 2022, a monkeypox outbreak linked to a piercing and tattoo establishment was reported to the Andalusian Epidemiological Surveillance System in Cádiz, Spain. Five individuals were diagnosed with monkeypox and all shared an epidemiological link. All five individuals had a history of ear piercing performed at the same facility, on July 6. Herein, we describe the clinical and epidemiological investigations of the first reported outbreak of monkeypox in a piercing and tattoo establishment in Europe, from July 19 to August 3.

Cases were notified to the Andalusian Epidemiological Surveillance System between July 19 and Aug 3, 2022. Vesicular lesion specimens were collected from each suspected case. Specific real-time PCR for monkeypox virus was performed and 20 individuals were identified to have the virus.

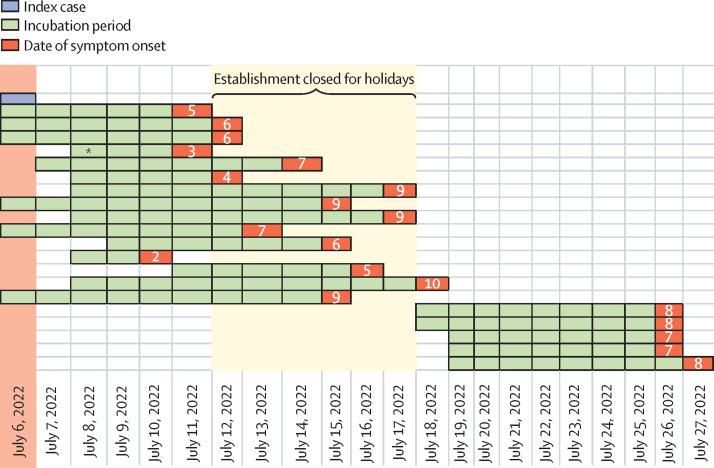

The piercing and tattoo establishment had only one worker, the owner. She did not present any epidemiological link or clinical picture related to the infection,6 nor did her family, pets, and social contacts. However, she reported being in contact with a possible index case on July 6. This client had travelled to Madrid for a social function in the previous days and, when attending the establishment, had inflammation of the area where the piercing was placed and generalised skin lesions, which he thought to be an adverse effect of taking antibiotics. It could not be confirmed whether this client had monkeypox because the owner had no list of clients; therefore, it was not possible to identify this person during the investigation. July 6 was considered to be the date of outbreak onset, given that the probable index case and all individuals with confirmed infection attended the establishment from July 6 onwards (figure ).

Figure.

Timeline of the incubation period of monkeypox virus and dates of symptom onset from July 6 to July 27, 2022

*Individual who had a tattoo done at the establishment.

54 exposed individuals were identified and the attack rate was 37%. Among the 20 individuals with confirmed infection, 13 (65%) were women and seven (35%) were men. Median age was 26 years [IQR 16–40; range 13–45 years). Eight (40%) individuals were younger than 18 years.

The predominant clinical feature was rash, found in all 20 individuals in the area of piercing or tattoo, although it also affected other locations. The most frequent first clinical manifestation was piercing or tattoo rash (18 [90%] individuals). Lymphadenopathy was present in 11 (55%) individuals, and the cervical location was the most frequent location (five [45%]). Fever was present in eight (40%) individuals. In all individuals, clinical symptoms were mild and no one required hospitalisation.

19 (95%) individuals reported a history of piercing, of whom 18 (95%) had an ear piercing. One (5%) person had a tattoo done on their forearm. None of the individuals with confirmed infection reported vaccination against smallpox, immunodeficiencies, or concurrent diseases. All 20 individuals were unaware of or reported no contact with a known case of monkeypox. 96 close contacts were identified, with no secondary cases reported.

During the official inspection of the establishment, numerous sanitary irregularities were found, such as poor hygiene and aseptic conditions.7 Surface sampling was performed on July 22, including three areas: the support work surfaces, the work tables and chairs, and sharps and other work instruments. All three samples were positive for monkeypox virus. A second sampling was performed on July 27, focusing on sharps and work tools. 15 (94%) of 16 samples were found to be positive for the virus, with tweezers and scissors tips having the highest viral load according to cycle threshold values.

Together, these findings suggest that monkeypox virus can be transmitted through exposure to contaminated piercing or tattoo material and, potentially through contaminated hands, due to poor aseptic measures and handling of materials.8

The epidemiological curve and the finding of monkeypox virus DNA on fomites and surfaces—more than 2 weeks after the probable index case attended the establishment—suggest an extended infectivity period of the virus.9 Of note, a rash first developed at the site of exposure, similar to what was observed for genital lesions in individuals with confirmed infection after sexual intercourse.10

To minimise the risk of further transmission, we continue to actively work with the community. This outbreak highlights that exposure to monkeypox virus during piercing and tattooing is a mechanism of viral transmission.

We declare no competing interests. This Comment would not have been possible without the contribution of many colleagues in the Andalusian health system. We thank the Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar team and the Bahía de Cádiz–La Janda team, for their important work in the outbreak investigation and control. We also thank all of the members of the Andalusian Epidemiological Surveillance System who have participated in the outbreak surveillance and all of the health-care professionals who collaborated in the diagnosis and management of patients.

References

- 1.WHO WHO Director-General's statement at the press conference following IHR Emergency Committee regarding the multi-country outbreak of monkeypox - 23 July 2022. July 23, 2022. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-the-press-conference-following-IHR-emergency-committee-regarding-the-multi--country-outbreak-of-monkeypox--23-july-2022

- 2.Martínez JI, Montalbán EG, Bueno SJ, et al. Monkeypox outbreak predominantly affecting men who have sex with men, Madrid, Spain, 26 April to 16 June 2022. Euro Surveill. 2022;27:2200471. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.27.2200471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Factsheet for health professionals on monkeypox. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/all-topics-z/monkeypox/factsheet-health-professionals

- 4.Ministerio de Sanidad Alerta de viruela de los monos en España y otros países de Europa. https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/alertaMonkeypox/home.htm

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Monkeypox: disinfecting home and other non-healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/specific-settings/home-disinfection.html

- 6.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Risk assessment: monkeypox multi-country outbreak. May 23, 2022. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/risk-assessment-monkeypox-multi-country-outbreak

- 7.Sindoni A, Valeriani F, Protano C, et al. Health risks for body pierced community: a systematic review. Public Health. 2022;205:202–215. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2022.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holbrook J, Minocha J, Laumann A. Body piercing: complications and prevention of health risks. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:1–17. doi: 10.2165/11593220-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Essbauer S, Meyer H, Porsch-Ozcürümez M, Pfeffer M. Long-lasting stability of vaccinia virus (orthopoxvirus) in food and environmental samples. Zoonoses Public Health. 2007;54:118–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2007.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antinori A, Mazzotta V, Vita S, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of four cases of monkeypox support transmission through sexual contact, Italy, May 2022. Euro Surveill. 2022;27:2200421. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.22.2200421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]