Abstract

Euonymus hamiltonianus and its relatives (Celastraceae family) are used for ornamental and medicinal purposes. However, species identification in Euonymus is difficult due to their morphological diversity. Using plastid genome (plastome) data, we attempt to reveal phylogenetic relationship among Euonymus species and develop useful markers for molecular identification. We assembled the plastome and nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrDNA) sequences from five Euonymus lines collected from South Korea: three Euonymus hamiltonianus accessions, E. europaeus, and E. japonicus. We conducted an in-depth comparative analysis using ten plastomes, including other publicly available plastome data for this genus. The genome structures, gene contents, and gene orders were similar in all Euonymus plastomes in this study. Analysis of nucleotide diversity revealed six divergence hotspots in their plastomes. We identified 339 single nucleotide polymorphisms and 293 insertion or deletions among the four E. hamiltonianus plastomes, pointing to abundant diversity even within the same species. Among 77 commonly shared genes, 9 and 33 were identified as conserved genes in the genus Euonymus and E. hamiltonianus, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis based on plastome and nrDNA sequences revealed the overall consensus and relationships between plastomes and nrDNAs. Finally, we developed six barcoding markers and successfully applied them to 31 E. hamiltonianus lines collected from South Korea. Our findings provide the molecular basis for the classification and molecular taxonomic criteria for the genus Euonymus (at least in Korea), which should aid in more objective classification within this genus. Moreover, the newly developed markers will be useful for understanding the species delimitation of E. hamiltonianus and closely related species.

Introduction

Euonymus hamiltonianus Wall., a plant belonging to the Celastraceae family, is widely distributed from Northern India to Far East Asia (http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org). E. hamiltonianus are valuable ornamental plants due to their beautiful shapes and colors. However, the morphological variations lead to ambiguous delimitation of this species. The uncertainty of species delimitation is not only the case for E. hamiltonianus but also for other closely related species. Fruit morphology of Euonymus was used to divide them into five sections, but molecular phylogeny of Euonymus was poorly supported in the previous study [1].

Although Celastraceae is a large family containing 96 genera and 1,350 species, few studies have been conducted for the genus Euonymus [2–4]. Universal DNA barcoding regions such as plastid matK, rbcL, and nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (nrITS) regions have been utilized to construct the phylogenies of Celastraceae [5–8]. Nevertheless, the intrageneric boundaries are still unclear due to the limitations of using a few short barcoding regions. To date, most studies in Euonymus have been conducted on individual species [9–12]. Even though an interspecies comparison of the Euonymus plastomes was recently conducted, no in-depth analysis of one species with its relatives has been performed [3]. Therefore, to address the plastome diversity and evolution of E. hamiltonianus and its relatives, it is important to conduct in-depth comparative analysis using various resources.

Plastomes have been widely employed for phylogenetic studies and DNA barcoding in various plants due to their uniparental inheritance (usually maternal inheritance) in most land plants [13]. Uniparental inheritance could reduce genetic diversity, but also provide simplicities in tracking ancestors (usually maternal) and obtaining genetic information with less heterogeneity [14]. In most land plants, plastid and mitochondrial genomes exhibit contrasting patterns in genomic features such as genome size, genome structure, gene content, and nucleotide substitution rates. Although plastomes have conserved genome structure and gene content, nucleotide substitution rates of plastid genes are generally faster than those of mitochondrial genes. In contrast, mitochondrial genomes display complicated genome structure and variable gene content, but substitution rates of mitochondrial genes are slower than those of plastid genes [15–18]. These genomic features have allowed plastomes to accumulate variations among species at a moderate rate [19,20].

Nuclear ribosomal DNAs such as 45S rDNA and 5S rDNA exist in a tandem repeat array of hundreds to thousands of copies and are genetically conserved due to concerted evolution [21,22]. However, the ITS regions, ITS1 between 18S and 5.8S and ITS2 between 5.8S and 26S, of the 45S rDNA are relatively variable at the sequence level. These characteristics of the nrDNA region provide useful genetic information for phylogenetic studies and DNA barcoding [23]. In addition, due to the development of Next Generations Sequencing (NGS) techniques, the assembly of complete plastome and 45S rDNA sequences can be performed quickly in a cost-effective manner. Complete plastome and 45S rDNA data generated by NGS platforms are quite helpful for species identification [24–29].

In this study, we assembled the complete plastomes and nrDNA (45S and 5S) sequences of five Euonymus plants by de novo assembly of low-coverage whole-genome shotgun sequencing (dnaLCW) [27,28]. We also conducted an in-depth analysis of the genetic features of other Euonymus plastomes using data from NCBI GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). The newly discovered genetic features of E. hamiltonianus and its relatives advance our understanding of the molecular identification and plastome evolution of these species.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and genome sequencing

Thirty-one E. hamiltonianus, one E. europaeus, and one E. japonicus were collected from various sources including wild and commercial samples (S6 Table). The collected samples from Hantaek Botanical Garden (Baegam, Cheoin, Yongin, Gyeonggi, Korea) and Sannae Botanical Garden (Byeongcheon, Dongnam, Cheonan, South Chungcheon, Korea) were collected with permission from garden authorities (Permitted by Taek Joo Lee and Myung Hyoe Kim, president of Hantaek Botanical Garden and Sannae Botanical Garden, respectively). For samples collected from the wild, no specific permission was required for collecting the species in this study, according to the national and local legislations. Leaf samples were collected, flash frozen, and used for genomic DNA extraction using an Exgene Plant SV Midi Kit and an Exgene Plant SV Mini Kit (Geneall Biotechnology, Seoul) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The concentration and quality of the extracted genomic DNA were examined by gel electrophoresis and with a Nanodrop 2000 spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). Among all 33 accessions, three E. hamiltonianus, one E. europaeus and one E. japonicus were used to generate paired-end (PE) libraries. The libraries were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform at Phyzen (www.phyzen.com, Seongnam, Republic of Korea). This analysis yielded 0.82–1.20 Gbp of sequencing data per sample.

Plastome and nrDNA assembly

All newly assembled plastomes and 45S rDNA were assembled using the dnaLCW method [27,28]. In summary, raw reads were trimmed by the trimming tool embedded in the CLC assembly cell. Trimmed reads were assembled into contigs by de novo assembly using the CLC assembly cell (ver.4.21, CLC Bio, Denmark). Among assembled contigs, only contigs with similarity to the reference plastome (E. hamiltonianus, NC_037518.1) were extracted by MUMmer and BLASTZ [30,31]. Finally, the plastome sequences were completed by manual curation. The completed plastomes were annotated using GeSeq (https://chlorobox.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/geseq) and Artemis [32,33].

Assembly of 45S rDNAs was performed in a similar manner following the pipeline used for plastome assembly. Only contigs with sequence similarity to the reference 45S rDNA (E. hamiltonianus, KY921875.1) were extracted. The start and end position of each 45S rDNA subunit (18S, ITS1, 5.8S, ITS2, and 26S) were determined using RNAmmer and the reference sequence [34].

Assembly of 5S rDNA was performed by reference mapping. Briefly, the draft sequence of 5S rDNA was assembled by mapping raw reads to the reference sequence of Arabidopsis thaliana (AF330993.1). After completing the assembly of 5S rDNA, the IGS region was assembled by mapping and elongation. Elongation of the IGS region was repeated until the mapped reads met the next 5S rDNA unit. Finally, the complete 5S rDNA unit with IGS sequences was confirmed via NCBI BLAST [35].

Comparative analysis of plastomes

In addition to the five newly assembled plastomes, five other previously reported Euonymus plastome sequences were obtained from NCBI GenBank (Table 1). The similarity among plastomes was confirmed by the mVISTA with LAGAN alignment method using E. hamiltonianus (NC_037518.1) as a reference sequence with default parameters [36,37]. Structural variations between junction regions were identified by IRscope (https://irscope.shinyapps.io/irapp/) [38].

Table 1. Information about the plastomes of members of the Euonymus genus examined in this study.

| Species | Length (bp) | Number of Genes | GenBank accession no. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | LSC | IR | SSC | CDS | tRNA | rRNA | ||

| E. hamiltonianus (Hantaek) | 157,360 | 86,399 | 26,322 | 18,317 | 87 | 37 | 8 | NC_037518.1 |

| E. hamiltonianus (Hongcheon) | 157,456 | 86,481 | 26,330 | 18,315 | 87 | 37 | 8 | MZ567069* |

| E. hamiltonianus (Jeju) | 157,511 | 86,518 | 26,339 | 18,315 | 87 | 37 | 8 | MZ567070* |

| E. hamiltonianus (’Snow’) | 157,536 | 86,532 | 26,340 | 18,324 | 87 | 37 | 8 | MZ567071* |

| E. europaeus | 157,263 | 86,245 | 26,344 | 18,330 | 87 | 37 | 8 | MZ567072* |

| E. japonicus | 157,628 | 85,909 | 26,700 | 18,319 | 88 | 37 | 8 | MZ567073* |

| E. japonicus | 157,637 | 85,903 | 26,697 | 18,340 | 88 | 37 | 8 | NC_028067.1 |

| E. fortunei | 157,639 | 85,855 | 26,719 | 18,346 | 88 | 37 | 8 | MH150885.1 |

| E. schensianus | 157,702 | 86,026 | 26,484 | 18,708 | 88 | 37 | 8 | NC_036019.1 |

| E. szechuanensis | 157,465 | 86,257 | 26,368 | 18,472 | 87 | 37 | 8 | NC_047463.1 |

LSC: Large Single Copy, IR: Inverted Repeat, SSC: Small Single Copy.

*: Newly assembled in this study.

To check the variants in whole plastomes, the ten Euonymus plastomes were aligned using the PRANK aligner with the +F option [39–41]. The aligned sequences were used to draw a plastome map and calculate the nucleotide diversity (pi value). Plastome gene and variation maps were drawn with circos-0.69–9 (http://circos.ca/) [42]. Pi values were calculated to estimate divergence hotspots in the whole plastome using DnaSP v6 by the sliding window method (window size: 600 bp, sliding size: 200 bp) [43].

Comparative analysis of protein-coding gene sequences

Ten Euonymus plastomes and one Catha edulis plastome (GenBank accession No.: KT861471) were used for comparative analysis. Among the 88 protein-coding genes, the sequences of 77 genes were collected because they were nonredundant and shared by the 11 individuals. The dN/dS analysis was performed on these common genes using a branch-site model (model: 2, NSsites: 2) of codeml in the paml version 3.14 package [44]. A likelihood-ratio test (LRT) was performed on the analyzed values to identify candidate genes (df = 1, p-value < 0.05). Only genes with > 0.7 posterior probability were selected as putative selected genes among the candidate genes.

Phylogenetic analysis

The 77 protein-coding gene sequences were independently aligned using PRANK aligner with the +F and translate option, and then were concatenated as a single supermatrix [39,40]. The concatenated supermatrix was used to reconstruct a plastome-based phylogenetic tree. The best substitution model for the supermatrix was selected by jModelTest version 2.1.10 via Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) analysis [45]. As a result, the GTR+Γ+I model was selected to be the best-fitting model. Based on the model test result, a Bayesian Inference (BI) tree was constructed using MrBayes v. 3.2.7 (rates = invgamma, ngen = 1,000,000, burninfrac = 0.25), while a Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree was constructed using RAxML GUI 2.0 with a rapid bootstrap test with 1,000 replicates and GTRGAMMAI [46,47].

To reconstruct the 45S rDNA phylogeny, species in Table 2 were aligned with MAFFT web version (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/) [48]. The substitution model was tested using the alignment sequences with jModelTest version 2.1.10 by AIC analysis [45]. Similar to the analysis with plastomes, GTR+Γ+I model was selected to be the best substitution model. With the selected model, ML and BI trees of 45S rDNA were constructed with the same condition for analyzing plastomes by RAxML GUI2.0 and MrBayes, respectively [46,47].

Table 2. Information about the nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrDNA) assembly of the six Euonymus accessions.

| Length (bp) | GenBank accession no. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions | 45S rDNA | 5S rDNA | ||||||

| Species | 18S RNA | ITS1 | 5.8S RNA | ITS2 | 26S RNA | 5S RNA | IGS | |

| E. hamiltonianus (Hantaek) | 1,809 | 237 | 164 | 216 | 3,398 | 121 | 343 | KY921875.1/MZ556116* |

| E. hamiltonianus (Hongcheon) | 1,809 | 237 | 164 | 215 | 3,398 | 121 | 343 | MZ520609*/MZ556115* |

| E. hamiltonianus (Jeju) | 1,809 | 237 | 164 | 216 | 3,398 | 121 | 343 | MZ520610*/MZ556116* |

| E. hamiltonianus (’Snow’) | 1,809 | 237 | 164 | 218 | 3,397 | 121 | 344 | MZ520611*/MZ556117* |

| E. europaeus | 1,809 | 237 | 164 | 216 | 3,397 | 121 | 347 | MZ520612*/MZ556118* |

| E. japonicus | 1,809 | 231 | 164 | 219 | 3,399 | 121 | 139 | MZ520613*/MZ556119* |

GenBank accession numbers for 45S (top) and 5S (bottom).

*: Newly assembled in this study.

Marker development and validation

Three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and three insertion or deletions (InDels) markers were developed based on the plastome variations among four E. hamiltonianus individuals. Three SNP markers were developed into dominant markers, while three InDel markers were codominant. All marker sets were subjected to in silico validation with NCBI Primer-BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) [49]. The newly developed markers were validated through gel-based analyses with 32 Euonymus samples. The following were the PCR amplification conditions: Initial denaturation: 94°C for 5 minutes, denaturation: 94°C for 20 seconds, annealing: 58°C for 20 seconds, extension: 72°C for 20 seconds, final extensions: 72°C for 7 minutes. Denaturation, annealing and extension were conducted 35 cycles. After that, the PCR amplicon was validated by 3% agarose gel with gel-electrophoresis. E. japonicus (section Ilicifolii) was excluded from this validation, because the species was phylogenetically distant from E. hamiltonianus and E. europaeus (sect. Euonymus). Grouping of each accession was conducted with PowerMarker v3.25 by the NJ method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates [50]. Finally, the consensus tree was retrieved by consensus with the phylip package version 3.697 [51].

Results

Characteristics of plastomes and nrDNA

We assembled complete plastomes, 45S nrDNA, and 5S nrDNA sequences from five Euonymus lines. By adding plastome sequences from NCBI, a total of ten complete plastomes, six 45S rDNA sequences, and six 5S rDNA sequences were compared in downstream analyses.

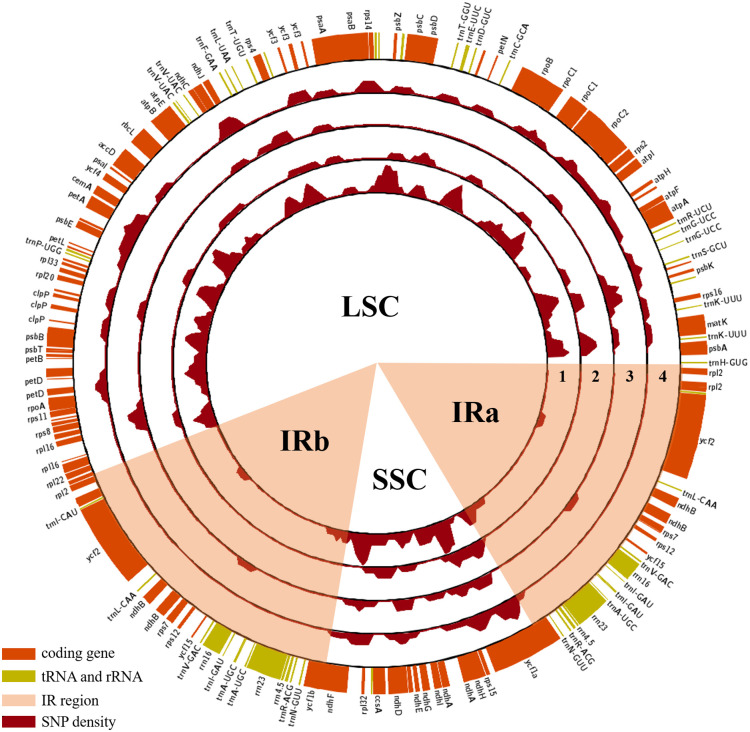

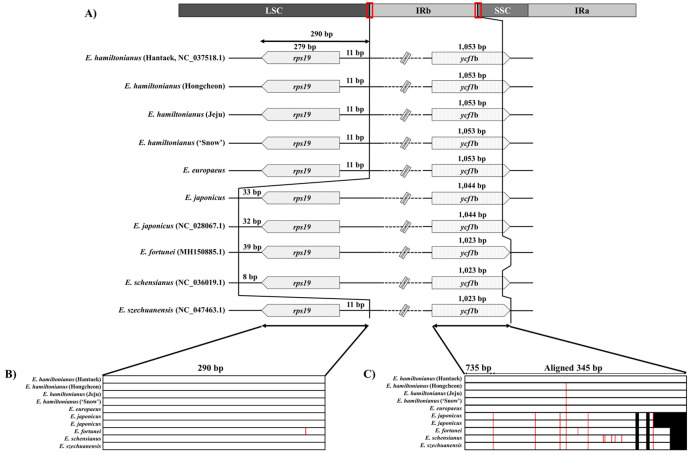

The genomes of these ten Euonymus plastomes ranged from 157,263 bp to 157,702 bp in size, with a quadripartite structure that is typical of plastomes in most plant species (Fig 1, Table 1). Each plastome consisted of a large single copy (LSC) region ranging from 85,855 bp to 86,532 bp, a small single copy (SSC) region of 18,315 bp to 18,708 bp, and two inverted repeats (IR) sequences ranging from 26,322 bp to 26,719 bp. Gene content and gene order were similar throughout the analyzed species. All ten Euonymus plastomes contained 87–88 protein-coding genes, 37 tRNA genes, and 8 rRNA genes. The gene numbers differed among species due to the rps19 gene. The rps19 gene was located in the LSC region of the E. hamiltonianus, E. europaeus and E. szechuanensis plastomes, whereas the gene was located in the IR region of the E. japonicus, E. fortunei and E. schensianus plastomes. Thus, species with rps19 located in the IR region had one more copy of the gene, while others only had one copy in the LSC region. Twenty-two genes were identified as multi-exon genes containing introns (S1 Table).

Fig 1. Gene map and plastome variations.

SNPs were measured in every 2 kb sliding window with a 500 bp sliding length. 1–4: Maximum variant number scale in each map is 6; 1. E. hamiltonianus (Hantaek)- specific SNP density map; 2. E. hamiltonianus (Hongcheon)-specific SNP density map; 3. E. hamiltonianus (Jeju)-specific SNP density map; 4. E. hamiltonianus (‘Snow’)-specific SNP density map.

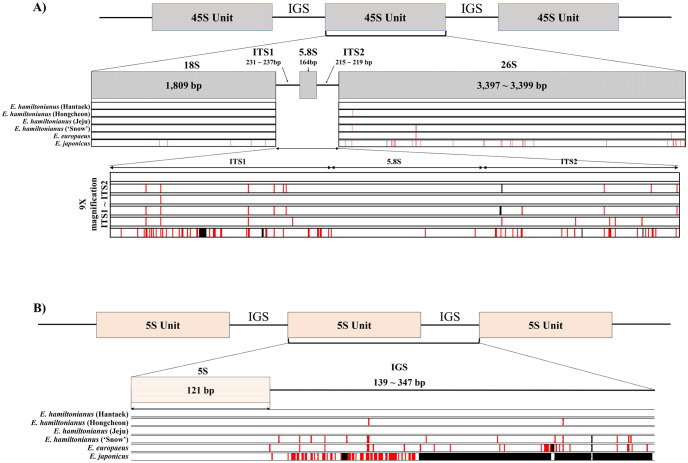

The six 45S rDNA sequences varied in length from 5,822 bp to 5,825 bp (Fig 2, Table 2). The lengths of specific regions of the six 45S rDNA sequences were similar: 1,809 bp for 18S regions, 231 bp to 237 bp for ITS1 regions, 164 bp for 5.8S regions, 215 bp to 219 bp for ITS2 regions, and 3,397 bp to 3,399 bp for 26S rDNA regions. Even though the sizes of 45S rDNAs were quite similar, E. japonicus showed a relatively divergent 45S rDNA sequence.

Fig 2. Genomic structures and diversity of rDNAs in Euonymus.

A and B show the structures of 45S rDNA and 5S rDNA, respectively. Variations are marked based on E. hamiltonianus (Hantaek) as a reference and are highlighted by red and black lines. Red and black lines indicate SNPs and InDels, respectively.

The 5S rDNA transcription unit sequences of E. hamiltonianus and E. japonicus were identical, and that of E. europaeus contained a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (Fig 2). By contrast, the sequences of intergenic spacer (IGS) regions significantly varied. The total length of the 5S unit and the IGS region ranged from 260 bp to 468 bp. Among the six Euonymus lines, E. japonicus had an exceptionally short IGS region compared to the five others, including E. hamiltonianus and E. europaeus. Furthermore, the assembled 5S rDNA repeat array existed independently from 45S rDNA, indicating that each nrDNA unit is independently repeated.

Plastome diversity among Euonymus lines

We evaluated the genome structures and sequence similarity of the ten Euonymus plastomes. Hundreds of SNPs (71–270) and InDels (70–213) were identified among the four E. hamiltonianus lines (Table 3). Each E. hamiltonianus accession showed unique patterns of SNP distribution (Fig 1 and S1 Fig). The IR regions were more conserved than the LSC and SSC regions. The sequences in protein-coding regions showed high similarity compared with those in non-coding regions. In particular, protein-coding genes in the IR region showed relatively high interspecies similarity than those in SC regions.

Table 3. Numbers of SNPs and InDels between the plastomes and 45S rDNA sequences of the four E. hamiltonianus accessions.

| InDel |

E. hamiltonianus (Hantaek) |

E. hamiltonianus (Hongcheon) |

E. hamiltonianus (Jeju) |

E. hamiltonianus (’Snow’) |

| SNP | ||||

|

E. hamiltonianus (Hantaek) |

- | 202/1 | 206/0 | 213/2 |

|

E. hamiltonianus (Hongcheon) |

247/10# | - | 70/1 | 100/2 |

|

E. hamiltonianus (Jeju) |

246/1 | 71/9 | - | 80/2 |

|

E. hamiltonianus (’Snow’) |

270/10 | 89/6 | 90/9 | - |

#Numbers of variations in plastomes/nrDNA are indicated for each comparison.

Even though structural variations were not detected, slight differences were found at the flanking sequence of the rps19 gene, which is conserved and duplicated in the IR regions of some Euonymus plastomes such as E. japonicus, E. fortunei, and E. schensianus (Fig 3A and 3B). In addition to variation in the rps19 gene, interspecies variation was found in the junctions of IRb and SSC regions (Fig 3B). There were three types of ycf1b genes in this junction based on length: 1,023 bp, 1,044 bp, and 1,053 bp (Fig 3C).

Fig 3. IR junctions in ten Euonymus plastomes.

A) In every species, rps19 is 279 bp long and is present at the IR junction. rps19 is present in the IR in four Euonymus individuals and in the LSC in six Euonymus individuals. The right IR junctions on the ycf1b genes are marked. B) and C) Nucleotide diversity in the left and right junctions, respectively. SNP and InDels are indicated by red and black lines, respectively. All variants are marked based on E. hamiltonianus (Hantaek) as a reference. The regions upstream of 735 bp in C) have no variants.

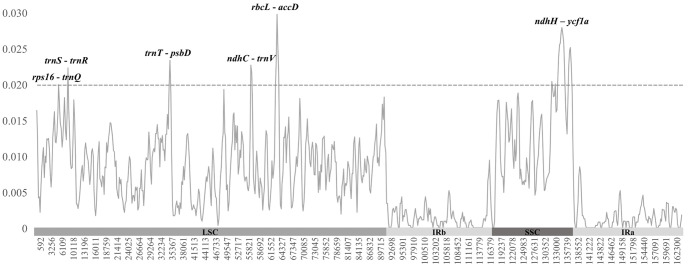

To identify divergence hotspot regions within the Euonymus plastome, we detected polymorphic sites and calculated the nucleotide diversity (pi value) (Fig 4). We identified 2,577 polymorphic sites in the ten Euonymus plastomes, with an aligned length of 153,495 bp (not including gap regions). Among the polymorphic sites, 1,767 sites (1.15%) were parsimony informative sites, while the remaining 810 sites (0.53%) were singleton sites. The pi value was calculated as 0.00695 throughout the plastome with sliding window methods (window size: 600bp, sliding length: 200bp). The individual windows had pi values ranging from 0 to 0.02993. The highest pi value was observed in the rbcL–accD region (0.02993). Six intergenic regions (rps16–trnQ, trnS–trnR, trnT–psbD, ndhC–trnV, rbcL–accD, and ndhH–ycf1a) had the higher pi values than the other regions (> 0.02). All six highly diverged regions were located in SC regions: five of these were located in the LSC region, and only one (ndhH–ycf1a) was located in the SSC region.

Fig 4. Pi value for each plastome region among the ten Euonymus lines.

The total pi value among whole plastomes was calculated as 0.00695 using DnaSP with the sliding window method. The sliding window size was 600 bp with a 200 bp sliding length. Six regions were estimated as divergence hotspots among Euonymus, as they had higher pi values (> 0.02). IR regions had lower pi values than SC regions (LSC and SSC).

Divergence of protein-coding genes in the Euonymus plastid genomes

To investigate sequence divergence of protein-coding genes in the Euonymus plastomes, we estimated the ratio of non-synonymous (dN) to synonymous (dS) substitution rates (dN/dS). Based on dN/dS ratios, no gene was estimated to be under positive selection (>1.0), which was similar to most seed plants [52–54]. However, no variation in coding sequence was identified in nine genes, including seven photosynthesis genes (psbI, psaI, psbJ, psbF, psbT, psbN, and ycf3) and two ribosomal protein genes (rpl36 and rps7). In addition, 15 genes (atpH, petN, psbM, psbD, psaB, psbE, petG, psaJ, rpl33, clpP, petD, infA, rps19, rpl23, and psaC) contained only synonymous substitution sites. In other words, these 24 genes had conserved protein-coding sequences in the Euonymus plastomes. Among the four E. hamiltonianus plastomes, 51 genes had conserved protein-coding sequences, 33 of which had no nucleotide variations.

Diversity of 45S and 5S nrDNA in Euonymus

Even though the 45S rDNA subunits were similar in length, many variations accumulated among species (Fig 2A). Each ribosome unit (18S, 5.8S, and 26S) had fewer variations than ITS regions. We identified 95 E. japonicus-specific SNPs and 17 SNPs in E. hamiltonianus and E. europaeus. Among the 112 SNPs identified, 5, 3, 34, and 70 were detected in 18S, 5.8S, 26S, and ITS regions, respectively (S2 Table).

The sequences of the 5S rDNA transcription unit were identical in E. hamiltonianus and E. japonicus, and one SNP was found in E. europaeus (Fig 2B). However, the sequences of IGS regions were quite variable. The IGS region was shorter in E. japonicus (139 bp) than in other species (343 to 347 bp) with abundant SNPs (Fig 2B).

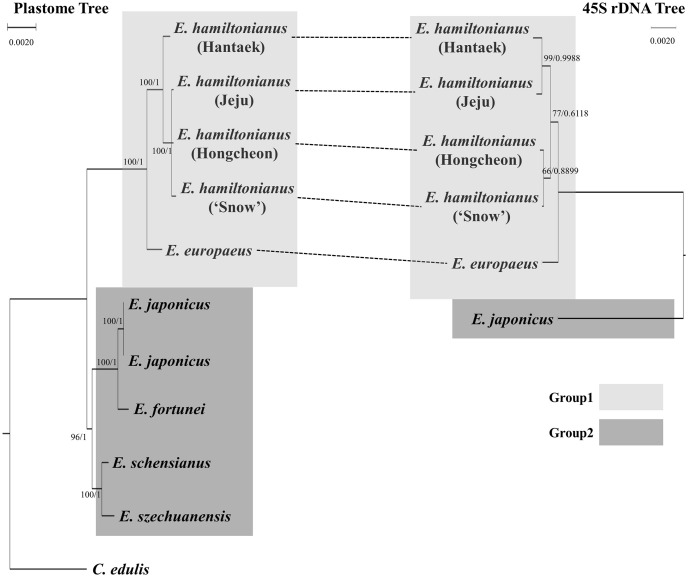

Phylogenetic analysis of Euonymus

The concatenated 77 protein-coding gene sequences were 62,724 bp in aligned length. Based on the supermatrix, the plastome-based phylogenetic tree of Euonymus was constructed by using C. edulis as an outgroup species. The plastome sequences from the ten Euonymus plastomes were divided into two groups in the phylogenetic tree (Fig 5 and S2 Fig). Group 1 contained all four accessions of E. hamiltonianus and E. europaeus, while Group 2 contained five other Euonymus lines (two E. japonicus accessions, E. fortunei, E. schensianus, and E. szechuanensis). The BI and ML trees showed almost identical topologies (S2 Fig). In Group 1, E. europaeus was sister to all four E. hamiltonianus accessions, and an E. hamiltonianus accession (Hantaek) was sister to the three other E. hamiltonianus accessions. However, the phylogenetic relationship inferred from nrDNA sequences was inconsistent with the results inferred from plastome sequences (Fig 5). In the nrDNA tree, two E. hamiltonianus accessions (Hantaek and Jeju) and the two other E. hamiltonianus accessions (Hongcheon and ‘Snow’) formed independent subclades, with sister relationships (Fig 5), suggesting that cytonuclear discordance could exist in this species. In Group 2, E. japonicus and E. fortunei formed a subclade, which was sister to the other subclade of E. schensianus and E. szechuanensis. We were not able to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships of species in Group 2 based on nrDNA data because the nrDNA sequences of E. fortunei, E. schensianus, and E. szechuanensis in Group 2 were not available (Fig 5).

Fig 5. Phylogenetic tree of the ten Euonymus accessions based on plastome and 45S rDNA sequences.

The tree on the left was drawn using common plastome coding sequences, and the tree on the right was drawn using common 45S rDNA sequences. The phylogenetic trees were constructed using the Bayesian Inference method. Bootstrap (ML method) and posterior probability values greater than 50% were shown. The supporting values separated by slash are bootstrap values and posterior probability, respectively.

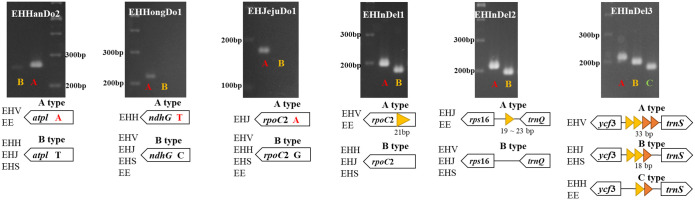

Marker development for the identification of diverse Euonymus hamiltonianus resources

We developed six DNA barcoding markers from three SNPs and three InDel regions in the E. hamiltonianus plastomes. Three SNP markers were developed from atpI, ndhG, and rpoC2 while three InDel markers were developed from rpoC2, intergenic regions between rps16–trnQ and ycf3–trnS (Fig 6, Table 4).

Fig 6. Representative genotypes and scheme used to develop barcoding markers.

EHV: E. hamiltonianus (Hantaek), EHH: E. hamiltonianus (Hongcheon), EHJ: E. hamiltonianus (Jeju), EHS: E. hamiltonianus (‘Snow’), EE: E. europaeus.

Table 4. Primers used in this study.

| Primer | Location | Accession | Product size (bp) | Strand | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHHanDo2 | atpI | EHV, EE | 270 | F | GTTGACCTACTTCCACAGGA |

| EHH, EHJ, EHS | - | R | CAATCGCTTTTTATTCCTGAATCG | ||

| EHHongDo1 | ndhG | EHH | 232 | F | AGGCCCAATCCCAGAAAGTT |

| EHV, EHJ, EHS, EE | - | R | GTGTCGAACTCTCCTTTGGG | ||

| EHJejuDo1 | rpoC2 | EHJ | 184 | F | CCGATTTTAGGTGTGGTGGA |

| EHV, EHH, EHS, EE | - | R | GGGAGAGTTTCTAAGCCCGA | ||

| EHInDel1 | rpoC2 | EHV, EE | 209 | F | CGAAGTTGCAGGTTTTCCCTT |

| EHH, EHJ, EHS | 188 | R | TTGATACCACCAGGAACGGT | ||

| EHInDel2 | rps16—trnQ | EHJ, EE | 224 | F | AATGGATCGGGAATCGGAGG |

| EHV, EHJ, EHS | 205 | R | TGATCCTAGAAAGATGAGAACATGG | ||

| EHInDel3 | ycf3—trnS | EHV | 224 | F | TGCTCGTGAGAAAACCACCA |

| EHJ, EHS | 209 | R | TCGAAACTACTCCATTTGGTTTGG | ||

| EHH, EE | 191 |

F: Forward; R: Reverse; EHV: E. hamiltonianus (Hantaek); EHH: E. hamiltonianus (Hongcheon); EHJ: E. hamiltonianus (Jeju); EHS: E. hamiltonianus (‘Snow’); EE: E. europaeus.

All six markers were successfully applied to 32 Euonymus lines, including 31 E. hamiltonianus accessions and one E. europaeus accessions (S4–S9 Figs). Based on the results, the 32 lines were divided into six groups (S3 Fig). Two accessions (28 and 29 in S3 Fig) showed a different genotype from the other accessions in Group 1. Despite the high intraspecies diversity in E. hamiltonianus, all E. hamiltonianus accessions were sympatrically separated with their exclusive genotypes (S5 Table). These results suggest that E. hamiltonianus accessions in Korea adapted to their specific environments and accumulated significant genetic divergence.

Discussion

Super-barcoding using complete plastome sequences for species identification

Although phylogenetic studies of the Celastraceae family have been performed using short barcoding regions [5–8], interspecies or intergeneric boundaries in this family have remained unclear due to the limited information provided by the short universal barcoding regions, such as rbcL and matK genes [24]. Moreover, mitochondrial plastid DNA (MTPT) has been reported in these barcoding genes in many plants [20,55,56]. Therefore, whole plastome sequences were proposed as an alternative source for developing useful markers for super-barcoding [25]. In this study, we obtained the complete plastome and nrDNA sequences of Euonymus species for use in species identification. The Euonymus species were clearly identified using these sequences, and the newly developed markers obtained in this study showed sufficient performance for the identification of different E. hamiltonianus accessions. Moreover, we inferred the divergence and evolutionary history of the genus Euonymus based on our newly assembled data. Therefore, complete plastomes could provide more precise information for accurate species authentication compared to short barcoding regions.

In this study, we developed six markers to distinguish individuals of E. hamiltonianus collected from various sources. According to marker validation results, it was possible to divide our E. hamiltonianus individuals into five groups (S3 Fig). Different marker combinations could be applied to identify the genotype of each group; Hantaek (EHV) genotype: EHHanDo2, EHInDel1, and EHInDel3. Hongcheon (EHH) genotype: EHHongDo1 and EHInDel3. Jeju (EHJ) genotype: EHJejuDo1. Cultivar ‘Snow’ (EHS) genotype:EHInDel2, and EHInDel3. Others: EHJejuDo1, EHInDel2, and EHInDel3. Single markers such as EHHongDo1 and EHInDel3 can be used to identify the Hongcheon genotype and Hantaek genotype, respectively. However, it would be better to use multiple markers to avoid misidentification. We expect that the six markers developed in this study will help to assess genotypes and genetic diversity for conservation of E. hamiltonianus.

Nuclear rDNA of Euonymus

In this study, we assembled the 45S rDNA and 5S rDNA transcription units with their ITS and IGS regions. The 45S rDNA transcription unit showed higher similarity than the ITS regions in these accessions. In addition, E. japonicus lines in Group 2 showed highly diverged sequences in their transcription units (Fig 2A). By comparing five newly assembled 45S rDNA sequences, we detected 21 SNPs and 3 InDels. Only seven variants showed homozygosity in all Euonymus lines. In the other variants, at least one individual showed heterozygosity (S3 Table). Therefore, caution should be taken when developing authentication markers based on nrDNA sequences. Even when markers are well designed, a heterozygotic position could interfere with the identification and interpretation of the results. A previous study showed that only 10% of non-target sequences could lead to a DNA marker paradox [20].

The complete 5S rDNA sequences showed high similarity among the Euonymus species (Fig 2B). However, the IGS sequence of E. japonicus (Group 2) differed from those of E. hamiltonianus and E. europaeus by having a shorter IGS (139 bp) with lower sequence homology. Such variations in the IGS sequence have been reported for other plants [57–60]. For example, differences in 5S rDNA sequences and reductions in repeat length were reported in Nicotiana tabacum and Solanum species, respectively [58,60].

Considering its sequence characteristics, the 5S rDNA tandem repeat array in Euonymus may have undergone a specific evolutionary event. Further research will be needed to elucidate the genomic characteristics and evolutionary history of the nuclear genomes of Euonymus species.

Divergence of the IR junctions in Euonymus

The expansion or contraction of IR regions is often observed in land plants [61–64]. Therefore, length variation in IR regions could be considered a common phenomenon in the plastomes of plants. As confirmed in our phylogenetic analysis (Fig 5), the ten Euonymus lines could also be divided into two groups. We predicted a divergence event in the Euonymus plastomes based on the results of phylogenetic analysis and differences in IR junctions. The Euonymus plastomes could be divided into two types based on the location of the rps19 gene. The plastomes of E. hamiltonianus, E. europaeus, and E. szechuanensis had shorter IR regions, and the rps19 gene was located in the LSC region (Fig 3), whereas an expansion of the IR containing the rps19 gene has occurred in the plastomes of E. japonicus, E. fortunei, and E. schensianus (Fig 3). Interestingly, our plastome-based phylogeny indicated that E. szechuanensis and E. schensianus formed an independent subclade, with different phylogenetic positions from the four other Euonymus species (Fig 5). This result is consistent with an infrageneric classification of the genus Euonymus [65]: E. hamiltonianus and E. europaeus belong to section Euonymus, E. japonicus and E. fortunei belong to section Ilicifolii, and E. szechuanensis and E. schensianus belong to section Uniloculares. On the other hand, another junction of IRb and SSC regions showed a similar pattern. The Euonymus plastomes were divided into three types based on the lengths of the ycf1b gene, which did not correspond to their phylogenetic relationships (Figs 3 and 5). Consequently, it is unclear whether the IR expansion/contraction occurred before or after the split of these three subclades (Fig 3). However, we hypothesize that the IR expansion/contraction event likely occurred recently after the split of these three sections based on the results of phylogenetic analysis and infrageneric classification of the genus Euonymus.

The ndhE in Euonymus might be under positive mutational pressure

Relatively higher dS and lower dN have widely been observed in plastid genes from most seed plants, and also in seed-free plants such as lycophytes and ferns [52–54,66,67]. Even though most genes would have undergone purifying selection (dN/dS < 1.0), estimating substitution rates of plastid genes in Euonymus is needed to understand the plastome evolution in this genus. As expected, we did not detect any gene under positive selection in our Euonymus plastome data. However, two genes (ndhE and rpoC1) had higher posterior probabilities than the other genes, with a significant p-value (< 0.05) (S4 Table). Both genes were located in the SC regions and detected in E. hamiltonianus. Most angiosperms contain 11 ndh genes which are involved in photosynthesis by producing NADH dehydrogenase subunits [68,69]. Products of these genes (NDH polypeptides) form a thylakoid NDH complex that functions in photosynthetic electron transfer [70]. The loss or pseudogenization of the ndh gene family has been reported in many plants [68,71,72]. In the current study, a comparison of the dN values of ndhE gene with 75 other genes suggested that ndhE might be under positive mutational pressure (S10 Fig). The dN value of the ndhE gene was two-times greater than the values of other genes. Therefore, it appears that ndhE is under relatively high mutational pressure in the three E. hamiltonianus accessions. Inspection of more diverse plastomes in Euonymus species should help clarify the active role of the ndhE gene in the divergence of these species.

Conclusions

In this study, we documented the complete plastomes of Euonymus species and performed comparative analysis. The plastome structures in the Euonymus genus were quite similar. However, the divergence of the Euonymus plastomes were revealed by comparing IR junctions and calculating pi values. We also confirmed the sequences and structures of nrDNAs in Euonymus. Phylogenetic analysis revealed possible cytonuclear discordance between the plastid and nuclear genomes, which we used to infer the times of IR expansion/contraction. The six molecular markers developed in this study will be useful for exploring genetic diversity of E. hamiltonianus distributed in South Korea. Further studies might help confirm the putative cytonuclear discordance between the organelle and nuclear genomes, as well as the divergence of the ndhE gene in E. hamiltonianus through large-scale data analysis.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thanks to all the staffs of Hantaek Botanical Garden, for providing plant collection used in this study.

Data Availability

All the data in this study were deposited in NCBI GenBank. The accession numbers of plastomes and rDNAs are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the NRF funded by the Korean government, MSIP (NRF-2015M3A9A5030733). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Li YN, Xie L, Li JY, Zhang ZX. Phylogeny of Euonymus inferred from molecular and morphological data. J Syst Evol. 2014; 52(2): 149–160. doi: 10.1111/jse.12068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz B. Studies of fruit and seed characters of selected Euonymus species.(Translated by Wolfgang Bopp). International Dendrology Society Yearbook; 2006. pp. 30–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Dong Y, Liu Y, Yu X, Yang M, Huang Y. Comparative analyses of Euonymus chloroplast genomes: Genetic structure, screening for loci with suitable polymorphism, positive selection genes, and phylogenetic relationships within Celastrineae. Front Plant Sci. 2020; 11: 2307. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.593984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christenhusz MJ, Byng JW. The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase. Phytotaxa. 2016; 261(3): 201–217. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.261.3.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacon CD, Simmons MP, Archer RH, Zhao L-C, Andriantiana J. Biogeography of the Malagasy Celastraceae: Multiple independent origins followed by widespread dispersal of genera from Madagascar. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2016; 94: 365–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simmons MP, Cappa JJ, Archer RH, Ford AJ, Eichstedt D, Clevinger CC. Phylogeny of the Celastreae (Celastraceae) and the relationships of Catha edulis (qat) inferred from morphological characters and nuclear and plastid genes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008; 48(2):745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simmons MP, Savolainen V, Clevinger CC, Archer RH, Davis JI. Phylogeny of the Celastraceae inferred from 26S nuclear ribosomal DNA, phytochrome B, rbcL, atpB, and morphology. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2001; 19(3): 353–366. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.0937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L-B, Simmons MP. Phylogeny and delimitation of the Celastrales inferred from nuclear and plastid genes. Syst Bot. 2006; 31(1): 122–137. doi: 10.1600/036364406775971778 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi KS, Park S. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Euonymus japonicus (Celastraceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 2016; 27(5): 3577–3578. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1075127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hua W, Chen C. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the plant Euonymus fortunei (Celastraceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2018; 3(2): 637–639. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1473724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J, Kang S-J, Shim H, Lee S-C, Kim N-H, Jang W, et al. Characterization of Chloroplast Genomes, Nuclear Ribosomal DNAs, and Polymorphic SSR Markers Using Whole Genome Sequences of Two Euonymus hamiltonianus Phenotypes. Plant Breed Biotechnol. 2019; 7(1): 50–61. doi: 10.9787/PBB.2019.7.1.50 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang W-C, Chen S-Y, Zhang X-Z. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of the golden crane butterfly, Euonymus schensianus (Celastraceae). Conserv Genet Resour. 2017; 9(4): 545–547. doi: 10.1007/s12686-017-0719-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greiner S, Sobanski J, Bock R. Why are most organelle genomes transmitted maternally? Bioessays. 2015; 37(1): 80–94. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Twyford AD, Ness RW. Strategies for complete plastid genome sequencing. Mol Ecol Resour. 2017; 17(5): 858–868. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer JD. Comparative organization of chloroplast genomes. Annu Rev Genet. 1985; 19(1): 325–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.19.120185.001545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer JD. Physical and gene mapping of chloroplast DNA from Atriplex triangularis and Cucumis sativa. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982; 10(5): 1593–1605. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.5.1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, Depamphilis CW, Müller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol Biol. 2011; 76(3): 273–297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaila T, Chaduvla PK, Saxena S, Bahadur K, Gahukar SJ, Chaudhury A, et al. Chloroplast genome sequence of Pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan (L.) Millspaugh) and Cajanus scarabaeoides (L.) Thouars: Genome organization and comparison with other legumes. Front Plant Sci. 2016; 7: 1847. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfe KH, Li W-H, Sharp PM. Rates of nucleotide substitution vary greatly among plant mitochondrial, chloroplast, and nuclear DNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987; 84(24): 9054–9058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park H-S, Jayakodi M, Lee SH, Jeon J-H, Lee H-O, Park JY, et al. Mitochondrial plastid DNA can cause DNA barcoding paradox in plants. Sci Rep. 2020; 10: 6112. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63233-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganley AR, Kobayashi T. Highly efficient concerted evolution in the ribosomal DNA repeats: total rDNA repeat variation revealed by whole-genome shotgun sequence data. Genome Res. 2007; 17(2): 184–191. doi: 10.1101/gr.5457707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovarik A, Matyasek R, Lim K, Skalická K, Koukalova B, Knapp S, et al. Concerted evolution of 18–5.8–26S rDNA repeats in Nicotiana allotetraploids. Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 2004; 82(4): 615–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2004.00345.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Álvarez I, Wendel JF. Ribosomal ITS sequences and plant phylogenetic inference. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003; 29(3): 417–434. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00208-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Group CPW, Hollingsworth PM, Forrest LL, Spouge JL, Hajibabaei M, Ratnasingham S, et al. A DNA barcode for land plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009; 106(31): 12794–12797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905845106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Yang Y, Henry RJ, Rossetto M, Wang Y, Chen S. Plant DNA barcoding: from gene to genome. Biological Reviews. 2015; 90(1): 157–166. doi: 10.1111/brv.12104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim K, Dong J, Wang Y, Park JY, Lee S-C, Yang T-J. Evolution of the Araliaceae family inferred from complete chloroplast genomes and 45S nrDNAs of 10 Panax-related species. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 4917. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05218-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim K, Lee S-C, Lee J, Yu Y, Yang K, Choi B-S, et al. Complete chloroplast and ribosomal sequences for 30 accessions elucidate evolution of Oryza AA genome species. Sci Rep. 2015; 5: 15655. doi: 10.1038/srep15655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim K, Lee S-C, Lee J, Lee HO, Joh HJ, Kim N-H, et al. Comprehensive survey of genetic diversity in chloroplast genomes and 45S nrDNAs within Panax ginseng species. PLoS One. 2015; 10(6): e0117159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen VB, Linh Giang VN, Waminal NE, Park HS, Kim NH, Jang W, et al. Comprehensive comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes from seven Panax species and development of an authentication system based on species-unique single nucleotide polymorphism markers. J Ginseng Res. 2020; 44(1): 135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, Smoot M, Shumway M, Antonescu C, et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 2004; 5: R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz S, Kent WJ, Smit A, Zhang Z, Baertsch R, Hardison RC, et al. Human–mouse alignments with BLASTZ. Genome Res. 2003; 13(1): 103–107. doi: 10.1101/gr.809403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tillich M, Lehwark P, Pellizzer T, Ulbricht-Jones ES, Fischer A, Bock R, et al. GeSeq–versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45(W1): W6–W11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carver T, Harris SR, Berriman M, Parkhill J, McQuillan JA. Artemis: an integrated platform for visualization and analysis of high-throughput sequence-based experimental data. Bioinformatics. 2012; 28(4): 464–469. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Stærfeldt H-H, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007; 35(9): 3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson M, Zaretskaya I, Raytselis Y, Merezhuk Y, McGinnis S, Madden TL. NCBI BLAST: a better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008; 36(suppl_2): W5–W9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004; 32(suppl_2): W273–W279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brudno M, Do CB, Cooper GM, Kim MF, Davydov E, Green ED, et al. LAGAN and Multi-LAGAN: efficient tools for large-scale multiple alignment of genomic DNA. Genome Res. 2003; 13(4): 721–731. doi: 10.1101/gr.926603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amiryousefi A, Hyvönen J, Poczai P. IRscope: an online program to visualize the junction sites of chloroplast genomes. Bioinformatics. 2018; 34(17): 3030–3031. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Löytynoja A. Phylogeny-aware alignment with PRANK. Methods Mol Biol. 2014; 1079: 155–170. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-646-7_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Löytynoja A, Goldman N. Phylogeny-aware gap placement prevents errors in sequence alignment and evolutionary analysis. Science. 2008; 320(5883): 1632–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1158395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao L-Z, Liu Y-L, Zhang D, Li W, Gao J, Liu Y, et al. Evolution of Oryza chloroplast genomes promoted adaptation to diverse ecological habitats. Commun Biol. 2019; 2: 278. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0531-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009; 19(9): 1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34(12):3299–3302. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Bioinformatics. 1997; 13(5): 555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012; 9(8): 772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edler D, Klein J, Antonelli A, Silvestro D. raxmlGUI 2.0: a graphical interface and toolkit for phylogenetic analyses using RAxML. Methods Ecol Evol. 2021; 12(2): 373–377. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.13512 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ronquist F, Teslenko M, Van Der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012; 61(3): 539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform. 2019; 20(4): 1160–1166. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye J, Coulouris G, Zaretskaya I, Cutcutache I, Rozen S, Madden TL. Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC bioinformatics. 2012; 13(1): 134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu K, Muse SV. PowerMarker: an integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics. 2005; 21(9): 2128–2129. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package) version 3.6. Distributed by the author. http://wwwevolutiongswashingtonedu/phyliphtml. 2004.

- 52.Guisinger MM, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Genome-wide analyses of Geraniaceae plastid DNA reveal unprecedented patterns of increased nucleotide substitutions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008; 105(47): 18424–18429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806759105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barnard-Kubow KB, Sloan DB, Galloway LF. Correlation between sequence divergence and polymorphism reveals similar evolutionary mechanisms acting across multiple timescales in a rapidly evolving plastid genome. BMC Evol Biol. 2014; 14: 268. doi: 10.1186/s12862-014-0268-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu J, Lindstrom AJ, Gong X. Towards the plastome evolution and phylogeny of Cycas L.(Cycadaceae): molecular-morphology discordance and gene tree space analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2022; 22: 116. doi: 10.1186/s12870-022-03491-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang D, Rousseau-Gueutin M, Timmis JN. Plastid sequences contribute to some plant mitochondrial genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2012; 29(7): 1707–1711. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gandini CL, Sanchez-Puerta MV. Foreign plastid sequences in plant mitochondria are frequently acquired via mitochondrion-to-mitochondrion horizontal transfer. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 43402. doi: 10.1038/srep43402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Souza TB, Gaeta ML, Martins C, Vanzela ALL. IGS sequences in Cestrum present AT-and GC-rich conserved domains, with strong regulatory potential for 5S rDNA. Mol Biol Rep. 2020; 47: 55–66. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-05104-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fulnecek J, Lim K, Leitch A, Kovarik A, Matyasek R. Evolution and structure of 5S rDNA loci in allotetraploid Nicotiana tabacum and its putative parental species. Heredity. 2002; 88: 19–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saini A, Jawali N. Molecular evolution of 5S rDNA region in Vigna subgenus Ceratotropis and its phylogenetic implications. Plant Syst Evol. 2009; 280: 187–206. doi: 10.1007/s00606-009-0178-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Volkov R, Zanke C, Panchuk I, Hemleben V. Molecular evolution of 5S rDNA of Solanum species (sect. Petota): application for molecular phylogeny and breeding. Theor Appl Genet. 2001; 103: 1273–1282. doi: 10.1007/s001220100670 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu A, Guo W, Gupta S, Fan W, Mower JP. Evolutionary dynamics of the plastid inverted repeat: the effects of expansion, contraction, and loss on substitution rates. New Phytol. 2016; 209: 1747–1756. doi: 10.1111/nph.13743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee HO, Joh HJ, Kim K, Lee S-C, Kim N-H, Park JY, et al. Dynamic Chloroplast Genome Rearrangement and DNA Barcoding for Three Apiaceae Species Known as the Medicinal Herb “Bang-Poong”. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20(9): 2196. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huo Y, Gao L, Liu B, Yang Y, Kong S, Sun Y, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of four Allium species: comparative and phylogenetic analyses. Sci Rep. 2019; 9: 12250. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48708-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gao C, Deng Y, Wang J. The complete chloroplast genomes of Echinacanthus species (Acanthaceae): phylogenetic relationships, adaptive evolution, and screening of molecular markers. Front Plant Sci. 2019; 9: 1989. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jin-shuang M, Michele F. Celastraceae. In: Wu ZY, Raven PH, Hong DY, editors. Flora of China Vol 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Beijing: Science Press; and Missouri Botanical Garden PressL St Louis; 2008. pp. 440–463. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kang JS, Zhang HR, Wang YR, Ling SQ, Mao Zy, Zhang XC, et al. Distinctive evolutionary pattern of organelle genomes linked to the nuclear genome in Selaginellaceae. Plant J. 2020; 104: 1657–1672. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang HR, Wei R, Xiang QP, Zhang XC. Plastome-based phylogenomics resolves the placement of the sanguinolenta group in the spikemoss of lycophyte (Selaginellaceae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2020; 147: 106788. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ruhlman TA, Chang W-J, Chen JJ, Huang Y-T, Chan M-T, Zhang J, et al. NDH expression marks major transitions in plant evolution and reveals coordinate intracellular gene loss. BMC Plant Biol. 2015; 15: 100. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0484-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lin C-S, Chen JJ, Huang Y-T, Chan M-T, Daniell H, Chang W-J, et al. The location and translocation of ndh genes of chloroplast origin in the Orchidaceae family. Sci Rep. 2015; 5: 9040. doi: 10.1038/srep09040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martín M, Sabater B. Plastid ndh genes in plant evolution. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010; 48(8): 636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chris Blazier J, Guisinger MM, Jansen RK. Recent loss of plastid-encoded ndh genes within Erodium (Geraniaceae). Plant Mol Biol. 2011; 76: 263–272. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9753-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin CS, Chen JJ, Chiu CC, Hsiao HC, Yang CJ, Jin XH, et al. Concomitant loss of NDH complex‐related genes within chloroplast and nuclear genomes in some orchids. Plant J. 2017; 90: 994–1006. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All the data in this study were deposited in NCBI GenBank. The accession numbers of plastomes and rDNAs are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.