Abstract

Background

Global pandemic of COVID-19 represents an unprecedented challenge. COVID-19 has predominantly targeted vulnerable populations with pre-existing chronic medical diseases, such as diabetes and chronic liver disease.

Aims

We estimated chronic liver disease-related mortality trends among individuals with diabetes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Utilizing the US national mortality database and Census, we determined the quarterly age-standardized chronic liver disease-related mortality and quarterly percentage change (QPC) among individuals with diabetes.

Results

The quarterly age-standardized mortality for chronic liver disease and/or cirrhosis among individuals with diabetes remained stable before the COVID-19 pandemic and sharply increased during the COIVD-19 pandemic at a QPC of 8.5%. The quarterly mortality from nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) increased markedly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mortality for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection declined with a quarterly rate of -3.3% before the COVID-19 pandemic and remained stable during the COVID-19 pandemic. While ALD- and HCV-related mortality was higher in men than in women, NAFLD-related mortality in women was higher than in men.

Conclusions

The sharp increase in mortality for chronic liver disease and/or cirrhosis among individuals with diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with increased mortality from NAFLD and ALD.

Keywords: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Alcohol-related liver disease, Cirrhosis, Hepatitis

Abbreviations: ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NVSS, National Vital Statistic System; QPC, quarterly percentage change

1. Introduction

Along with the rising prevalence of diabetes worldwide, the age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes increased markedly among adults aged ≥ 18 years from 1999 to 2016, corresponding to 34.1 million adults having diabetes in the United States (US) [1]. Based on data from the National Vital Statistic System (NVSS), diabetes has remained steady in its ranking as the seventh leading underlying cause of death in the US [2]. However, the age-standardized national mortality due to diabetes declined from 112 per 100,000 individuals in 2007 to 104 per 100,000 in 2017 in the US [3]. Individuals with diabetes demonstrated a two to three-fold increased risk for chronic liver disease-related mortality [4,5]. In terms of cause-specific death among individuals with diabetes listed on the death certificate, the deaths for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer decreased by 1% per year [3], while cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)-related mortality increased at an annual rate of 1.2–1.9% between 2007 and 2017 [6]. Since severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first documented in late 2019, the confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have now exceeded six hundred million across the world [7]. COVID-19 has predominantly targeted vulnerable populations with pre-existing chronic medical diseases, such as diabetes and chronic liver disease. In addition, it is prudent to assume that interruptions in standard-of-care and/or due to COVID-19 among individuals with pre-existing chronic illnesses, such as diabetes and chronic liver disease, may have indirectly and/or directly contributed to morbidity and mortality during the COIVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we used the up-to-date national mortality data (the NVSS 2017–2020) to estimate the latest trends in chronic liver disease-related mortality among individuals with diabetes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study data

We utilized a previously described method for this analysis [3,6]. In brief, we performed analyses using a de-identified national mortality dataset from the NVSS (2017–2020), in which the causes of death were recorded based on the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). This dataset captures more than 99% of deaths in all US states. Due to the de-identified and publicly available dataset, this study did not require approval by the Institutional Review Board at our institution.

2.2. Definitions of diabetes and chronic liver disease-related death

We defined chronic liver disease-related deaths using underlying and contributing causes of death among individuals with diabetes listed on the underlying or contributing cause of death (E10-E14). We also defined chronic liver disease-related deaths using the underlying cause of death among individuals with diabetes for a sensitivity analysis. We identified cirrhosis as cirrhosis (K70.3, K74.0, K74.1, K74.2, K74.3, K74.4, and K74.6) or portal hypertension (K76.6), or one of its complications: variceal bleeding (I85.0 and I85.1), hepatic encephalopathy (K72.11 and K72.91), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (K65.2), or hepatorenal syndrome (K76.7). We defined alcohol-related liver disease (ALD; K70.0, K70.1, K70.2, K70.3, K70.4, and K70.9), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD; K76.0 and K75.81), chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (B17.1, B18.2, and B19.2), chronic hepatitis B virus infection (B16, B17.0, B18.0, B18.1, and B19.1), and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC; C22.0). We identified individuals with chronic HCV infection and ALD as having HCV infection. We defined chronic liver disease by including the above clinical diagnosis. COVID-19 deaths are classified as ICD-10 code U07.1 [8].

2.3. Statistical analysis

The method for statistical analysis has previously been described [9], [10], [11]. In brief, to determine the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mortality from diabetes and chronic liver disease, we estimated quarterly (3-month period) age-specific mortality by age group (20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and ≥ 80 years) by dividing the number of deaths according to the total US Census population for each year and were standardized to the 2010 US standard population's age distribution. To examine temporal trends before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, the quarterly percentage change (QPC) and the average QPC, a summary measure of trends explaining transitions within each trend segment, were calculated using the joinpoint regression (version 4.9.0.1; National Cancer Institute).

3. Results

3.1. Age-Standardized mortality for chronic liver disease among individuals with diabetes

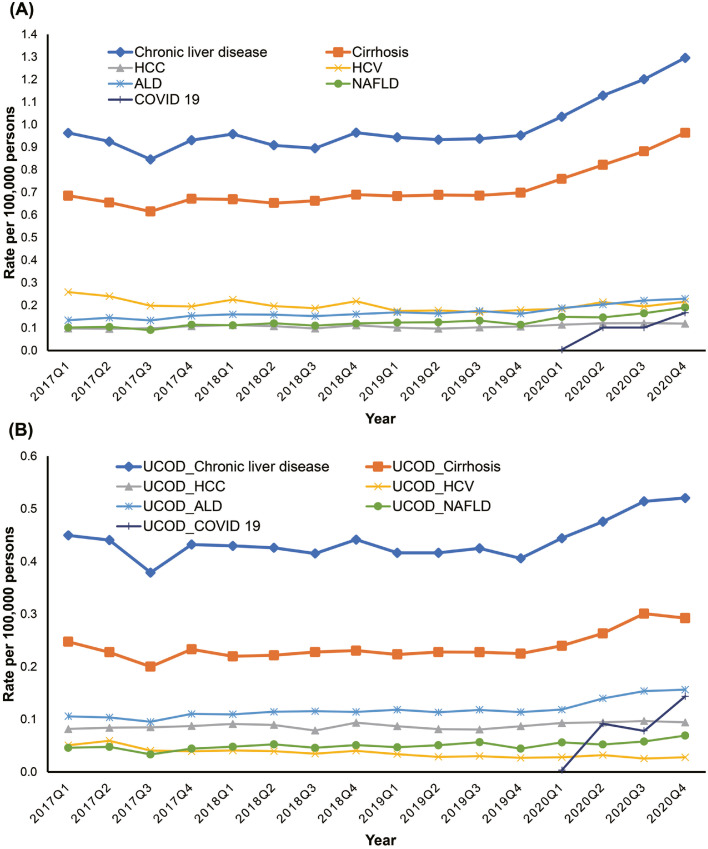

The study population consisted of 43,436 deaths from chronic liver disease as the underlying or contributing cause of death among 1218,968 deaths from all-cause mortality due to diabetes listed as the underlying or contributing cause of death from 2017 to 2020. Among individuals with diabetes listed on death certificates (Fig. 1 A and Table 1 ), the quarterly age-standardized mortality for chronic liver disease as an underlying or contributing cause of death increased with an annual rate of 2.7% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.9% to 3.5%). The quarterly mortality for chronic liver disease remained stable before the COVID-19 pandemic (QPC: 0.6%, 95% CI: −0.0% to 1.2%, P = 0.052) and sharply increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (QPC: 8.6%, 95% CI: 5.5% to 11.6%). Comparable to chronic liver disease-related mortality, mortality due to cirrhosis remained stable before the COVID-19 pandemic (QPC: 0.3%, 95% CI: −0.4% to 1.1%) and increased at a rate of 8.4% (95% CI: 4.6% to 12.3%) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The quarterly mortality for HCC increased steadily during the study (QPC: 1.2%, 95% CI: 0.5% to 1.9%). Based on the etiology-specific analysis, a steady increase in mortality due to NAFLD and ALD was observed at a rate of 4.2% (95% CI: 2.5% to 5.9%) and 3.5% (95% CI: 2.4% to 4.7%) during the study. The quarterly mortality due to NAFLD (QPC: 9.6%, 95% CI: 3.3% to 16.3%) and ALD (QPC: 7.7%, 95% CI: 3.5% to 12.0%) increased markedly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mortality for HCV infection declined with a quarterly rate of −3.3% (95% CI: −5.2% to −1.3%) before the COVID pandemic and remained stable during the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19-related mortality as the underlying or contributing cause of death among individuals with chronic liver disease and diabetes listed on death certificates increased from 0.004 per 100,000 persons in 2020 Q1 to 0.2 per 100,000 persons in 2020 Q4, accounting for 10% of deaths among individuals with chronic liver disease and diabetes. When we defined chronic liver disease as an underlying cause of death among individuals with diabetes, the overall results remained identical (Fig. 1B and Table 1). The quarterly age-standardized mortality for chronic liver disease and cirrhosis showed similar trends, with a sharp increase during the COVID-19 pandemic (QPC: 6.3%, 95% CI: 1.8% to 11.0% for chronic liver disease and QPC: 7.9%, 95% CI: 2.3% to 13.7% for cirrhosis). For NAFLD, quarterly mortality steadily increased during the study years (QPC: 2.4%, 95% CI: 1.0% to 3.8%), while quarterly mortality for ALD showed a sharp increase during the COVID-19 pandemic (QPC: 10.4%, 95% CI: 3.3% to 17.9%).

Fig. 1.

Quarterly age-standardized chronic liver disease-related mortality among individuals with diabetes listed on death certificates in the united states, from 2017 to 2020.

(A) Trends in chronic liver disease-related mortality as the underlying or contributing cause of death.

(B) Trends in chronic liver disease-related mortality as the underlying cause of death.

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus infection; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; UCOD, underlying cause of death.

Table 1.

Quarterly age-standardized chronic liver disease-related mortality and quarterly percentage change (QPC) among US adults (≥ 20 Years) with diabetes listed on the death certificate in 2017–2020.

| Age-standardized rate (per 100,000 individuals) |

Average QPC (95% CI) | Trend segment 1 |

Trend segment 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 Q1 | 2019Q4 | 2020 Q4 | 2017–2020 | Year | QPC (95% CI) | Year | QPC (95% CI) | |

| All-cause mortality among individuals listed on diabetes | ||||||||

| Chronic liver disease | 0.96 | 0.95 | 1.30 | 2.7 (1.9, 3.5)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | 0.6 (−0.0, 1.2) | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 8.6 (5.5, 11.6)* |

| Cirrhosis | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.96 | 2.4 (1.4, 3.4)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | 0.3 (−0.4, 1.1) | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 8.4 (4.6, 12.3)* |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 1.2 (0.5, 1.9)* | ||||

| Alcohol-related liver disease | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 3.5 (2.4, 4.7)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | 2.1 (1.2, 2.9)* | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 7.7 (3.5, 12.0)* |

| Hepatitis C | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.22 | −0.7 (−2.7, 1.4) | 2017 Q1–2019 Q3 | −3.3 (−5.2, −1.3)* | 2019 Q3–2020 Q4 | 4.7 (−1.1, 10.9) |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 4.2 (2.5, 5.9)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | 2.3 (1.0, 3.6)* | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 9.6 (3.3, 16.3)* |

| Underlying cause of death among individuals listed on diabetes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic liver disease | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 1.4 (0.2, 2.7)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | −0.3 (−1.2, 0.7) | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 6.3 (1.8, 11.0)* |

| Cirrhosis | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 2.0 (0.6, 3.5)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | −0.0 (−1.1, 1.1) | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 7.9 (2.3, 13.7)* |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.7 (0.1, 1.4)* | ||||

| Alcohol-related liver disease | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 3.1 (1.9, 4.5)* | 2017 Q1–2020 Q1 | 1.4 (0.6, 2.2)* | 2020 Q1–2020 Q4 | 10.4 (3.3, 17.9)* |

| Hepatitis C | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −4.4 (−5.6, −3.2)* | ||||

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 2.4 (1.0, 3.8)* | ||||

Abbreviation: QPC, quarterly percentage change; Q, quarter; CI, confidence interval.

All-cause mortality was combined underlying cause of death and contributing causes through the record axis.

P<0.05.

3.2. Trends in mortality for chronic liver disease among individuals with diabetes by sex

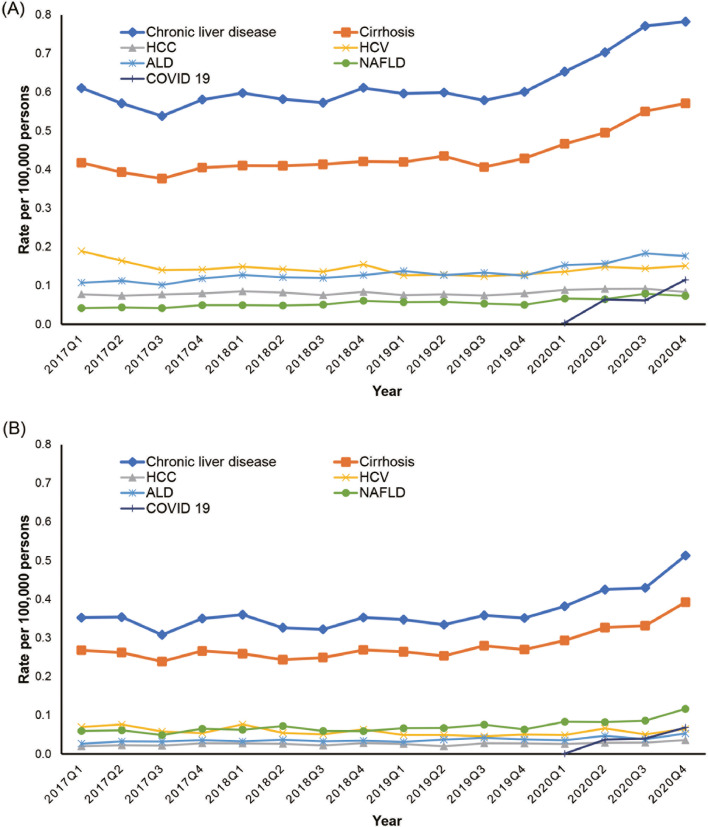

When we analyzed mortality by sex, chronic liver disease- and cirrhosis-related mortalities in men with diabetes were higher than in women with diabetes (Fig. 2 and Table 2 ). However, trends in chronic liver disease- and cirrhosis-related mortalities were slightly steeper in women (QPC: 2.6%, 95% CI: 1.1% to 4.1% for chronic liver disease; QPC: 2.8%, 95% CI: 1.4% to 4.1% for cirrhosis) than in men (QPC: 2.3%, 95% CI: 1.3% to 3.3% for chronic liver disease; QPC: 2.6%, 95% CI: 1.7% to 3.5% for cirrhosis). Consistent with the total population, mortality due to chronic liver disease and cirrhosis remained stable before the COVID-19 pandemic and increased at a QPC rate of about 7.8% for men and 9.5% for women during the COVID-19 pandemic. When we analyzed etiology-based mortality by sex (Fig. 2 and Table 2), ALD-related mortality in men was more than 3-fold higher than in women. Quarterly ALD-related mortality in women steadily increased before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, ALD-related mortality in men mildly increased before the COVID-19 pandemic (QPC: 2.2%, 95% CI: 1.0% to 3.3%) and markedly increased at a rate of 8.0% (95% CI: 2.4% to 13.8%) during the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, NAFLD-related mortality in women was higher than in men. While quarterly NAFLD-related mortality in men steadily increased before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, NAFLD-related mortality in women markedly increased at a rate of 11.7% (95% CI: 0.9% to 23.5%) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mortality for HCV infection declined with a quarterly rate of −2.9% for men and −4.0% for women before the COVID pandemic and remained stable during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 2.

Quarterly age-standardized chronic liver disease-related mortality among individuals with diabetes listed on death certificates based on the sex in the United States, from 2017 to 2020.

(A) Trends in chronic liver disease-related mortality as the underlying or contributing cause of death in men.

(B) Trends in chronic liver disease-related mortality as the underlying or contributing cause of death in women.

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus infection; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Table 2.

Quarterly age-standardized chronic liver disease-related mortality and quarterly percentage change (QPC) among US adults (≥ 20 Years) with diabetes listed on the death certificate based on the sex in 2017–2020.

| Age-standardized rate (per 100,000 individuals) |

Average QPC (95% CI) | Trend segment 1 |

Trend segment 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 Q1 | 2019Q4 | 2020 Q4 | 2017–2020 | Year | QPC (95% CI) | Year | QPC (95% CI) | |

| Men | ||||||||

| Chronic liver disease | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.78 | 2.3 (1.3, 3.3)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | 0.4 (−0.4, 1.1) | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 7.7 (3.9, 11.5)* |

| Cirrhosis | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 2.6 (1.7, 3.5)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | 0.7 (0.0, 1.4)* | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 7.9 (4.6, 11.4)* |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.9 (0.2, 1.6)* | ||||

| Alcohol-related liver disease | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 3.7 (2.2, 5.2)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | 2.2 (1.0, 3.3)* | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 8.0 (2.4, 13.8)* |

| Hepatitis C | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.15 | −0.6 (−2.4, 1.3) | 2017 Q1–2019 Q3 | −2.9 (−4.6, −1.2)* | 2019 Q3–2020 Q4 | 4.3 (−0.8, 9.7) |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 3.7 (2.7, 4.7)* | ||||

| Women | ||||||||

| Chronic liver disease | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 2.6 (1.1, 4.1)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | 0.2 (−0.9, 1.3) | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 9.5 (3.9, 15.4)* |

| Cirrhosis | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 2.8 (1.4, 4.1)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | 0.4 (−0.6, 1.4) | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 9.5 (4.4, 14.7)* |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 2.3 (0.8, 3.8)* | ||||

| Alcohol-related liver disease | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 2.8 (1.5, 4.1)* | ||||

| Hepatitis C | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.9 (−4.2, 2.6) | 2017 Q1–2019 Q3 | −4.0 (−7.2, −0.8)* | 2019 Q3–2020 Q4 | 5.8 (−3.9, 16.4) |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 4.2 (1.4, 7.2)* | 2017 Q1–2019 Q4 | 1.7 (−0.5, 3.9) | 2019 Q4–2020 Q4 | 11.7 (0.9, 23.5)* |

Abbreviation: QPC, quarterly percentage change; Q, quarter; CI, confidence interval.

P<0.05.

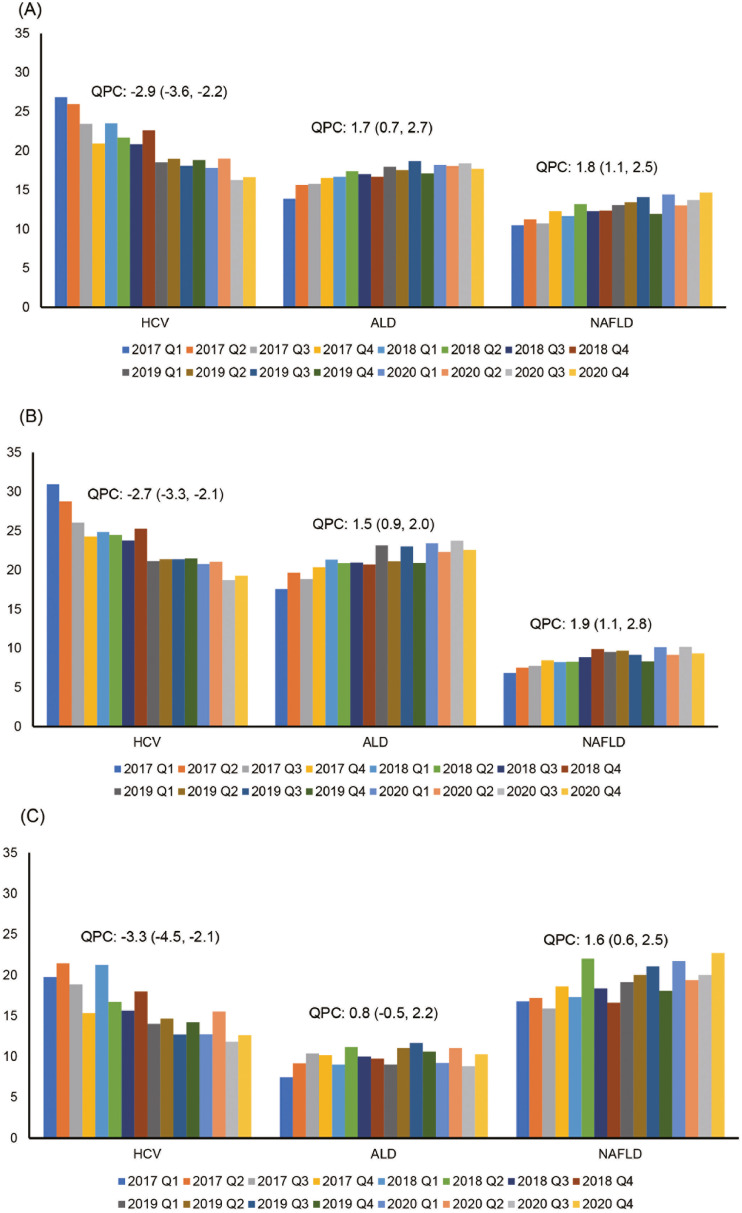

3.3. The proportion of etiology-based chronic liver disease-related mortality among individuals with diabetes

As shown in Fig. 3 A, trends in the proportion of HCV-related mortality among individuals with chronic liver disease and diabetes decreased with a quarterly decline of −2.9% (95% CI: −3.6% to −2.2%), while quarterly trends in the proportion of NAFLD- and ALD-related mortality among individuals with chronic liver disease and diabetes increased with a quarterly increase of 1.8% (95% CI: 1.1% to 2.5% for NAFLD) and 1.7% (95% CI: 0.7% to 2.7% for ALD). When we analyzed trends in the proportion of etiology-based mortality by sex, the results were largely identical (Fig. 3B and 3C). However, there was a notable difference in the proportion of NAFLD and ALD between men and women. The proportion of NAFLD-related mortality among individuals with diabetes and chronic liver disease was more than 2-fold higher in women than in men, while the proportion of ALD-related mortality was over 2-fold higher in men than in women.

Fig. 3.

Quarterly Trends in Proportion of Etiology-based Chronic Liver Disease-related Mortality among Individuals with Diabetes Listed on Death Certificate in the United States from 2017 to 2020.

(A) Total Population.

(B) Men.

(C) Women.

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus infection; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; QPC, quarterly percentage change.

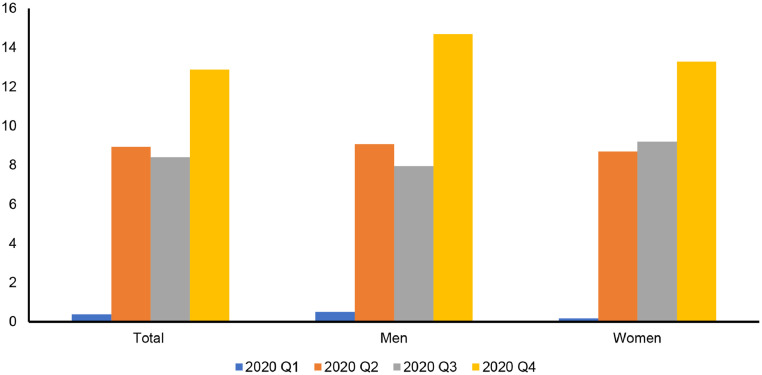

COVID-19-related mortality among individuals with chronic liver disease and diabetes was 0.4% for 2020 Q1, 8.9% for 2020 Q2, 8.4% for 2020 Q3, and 12.9% for 2020 Q4 (Fig. 4 ). There was no considerable difference between men and women.

Fig. 4.

Quarterly Trends in Proportion of COVID-19-related Mortality among Individuals with Diabetes and Chronic Liver Disease Listed on Death Certificate in the United States in 2020.

4. Discussion

In this US population-based study using national representative mortality data, we noted that the quarterly mortality for chronic liver disease and/or cirrhosis among individuals with diabetes remained stable before the COVID-19 pandemic and sharply increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a quarterly increase of approximately 8.5%, in association with the rise in quarterly mortality for NAFLD and ALD. While a decline in HCV-related mortality was prominent before the COVID-19 pandemic, mortality for NAFLD and ALD among individuals with diabetes steadily increased before the COVID-19 pandemic and demonstrated a more rapid increase during the COVID-19 pandemic. The proportion of COVID-19-related mortality among individuals with diabetes and chronic liver disease sharply increased up to 13%, corresponding to the proportion of deaths from each etiology-based chronic liver disease.

Recently, the role of sex as a modifier of the most common causes of morbidity and death in chronic diseases is a rapidly growing area in medicine [12,13]. Diabetes is a more potent risk factor for the onset of cardiovascular disease and cancer in women than in men [12]. Sex influences on chronic liver disease are cause-specific, with men exhibiting a higher risk of chronic viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, and HCC, whereas women exhibit a higher risk of autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cholangitis [12]. We found that chronic liver disease- and cirrhosis-related mortalities in men were higher than in women. However, trends in chronic liver disease- and cirrhosis-related mortalities were slightly higher in women than men. ALD is more common in men because men have a higher alcohol consumption than women, although the threshold of alcohol consumption that results in ALD in women is half that of men [12]. In this study, ALD-related mortality in men was more than 3-fold higher than in women. In contrast, NAFLD-related mortality in women was more than 2-fold higher than in men. The prevalence and severity of NAFLD are higher in men than women during reproductive age [13]. However, after menopause, NAFLD occurs at a higher rate in women, suggesting that estrogen is protective [13]. We found that 90% of NAFLD-related deaths were over 50 years, which may not be a protective age for women. A recent meta-analysis showed that women had a 19% lower risk of NAFLD than men; however, risks of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and advanced fibrosis were substantially higher in women in populations over 50 years [14]. Therefore, while men are more exposed to the risk of developing NAFLD, women could be more exposed to progressive liver disease, resulting in increased mortality risk [14]. However, the exact mechanism to explain the discrepancy is not fully understood, and further studies are needed to elaborate on this finding.

Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance may partially explain the association between diabetes and chronic liver disease through hepatic inflammation, insulin-like growth factor, and various pro-inflammatory cytokines that may be associated with or linked to the pathogenesis of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis [15]. The presence of chronic liver disease-related morbidity in the setting of diabetes led to an increase in resource utilization and a significantly higher risk of mortality [16]. Our observations confirm that COVID-19 had a higher likelihood of impacting vulnerable populations with pre-existing chronic liver diseases and diabetes, with a death rate as high as 10% in individuals with co-existing chronic liver disease and diabetes. The inability to attend regular outpatient clinics for close monitoring and treatment accompanied by diversion of health care resources to COVID-19 care may have resulted in the suboptimal or delayed clinical care of individuals with diabetes and chronic liver disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Individuals with ALD are one of the impacted sub-cohort during the COVID-19 pandemic. This vulnerability includes a higher risk of severe COVID-19 due to a disrupted immune system and high-risk comorbidities [17]. The inability to attend regular outpatient visits with providers and social isolation leading to the mental health crisis and an upsurge in harmful drinking and relapse alongside barriers to cessation services may be reasons for a dramatic rising tide of mortality due to ALD, not COVID-19, during the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. The pandemic has also propagated unhealthy lifestyles predisposing to NAFLD. A US study showed that half of Americans gained weight during the COVID-19 pandemic. Being overweight before the pandemic was most likely to gain weight (65%) compared with those who reported being normal-weight (40%) [18]. A recent study reported that metabolic-associated fatty liver disease was highly prevalent at the time of hospital discharge and represented a specific post-acute COVID syndrome, which may affect increased mortality among survivors of COVID-19 [19]. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease represented a specific post-acute COVID syndrome-cluster phenotype, with potential health consequences from cardiovascular and metabolic abnormalities in long-COVID-19 [19]. The recent approval of highly efficacious and tolerant direct-acting anti-viral agents, which could have provided HCV-related end-stage liver disease, may have been crucial in reducing fatalities [20]. Mortality for HCV infection among individuals with diabetes declined with a quarterly rate of −3.3% before the COVID pandemic and remained stable during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may be partially explained by developing extrahepatic manifestations and COVID-19.

As its strength, our study provides an update on national longitudinal trends in etiology-based chronic liver disease-related mortality among individuals with diabetes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, with clear insight and understanding into the contribution of cause-specific COVID-19-related mortality. However, our study has the potential for misclassification and underestimation of mortality due to diabetes and chronic liver disease because of errors in the documentation on death certificates. Over time, the coding method has been constant, so we believe it is unlikely to explain the presented temporal trends by erroneous coding or documentation. In addition, the number of deaths associated with hepatitis B virus infection was too small to present specific results because the NVSS did not allow it due to the possibility of identity.

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged and stretched the resources of healthcare systems, policymakers, and governments. We must focus on improving our understanding and knowledge of the direct and indirect influence of COVID-19 on co-existing chronic liver disease and diabetes. It is plausible that psychosocial stress and a higher predisposition to psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic can increase the risk of alcohol use disorder and ALD. Furthermore, it is prudent to suspect that COVID-19-related lockdowns may increase the risk of obesity, leading to a higher risk of insulin resistance and metabolic complications, including diabetes and NAFLD. Future studies are needed to improve our understanding of these possible pathogenetic links. More importantly, emergency preparedness or contingency plans must be in place to continue and provide uninterrupted care for chronic ailments during times of disaster.

Authors contributions

Donghee Kim was responsible for study concept and design, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approval of the final draft manuscript.

Omar Alshuwaykh, Brittany B. Dennis, George Cholankeril, and Joshua W. Knowles were responsible for the interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approval of the final draft manuscript.

Aijaz Ahmed was responsible for study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, approval of the final draft manuscript, and supervision of the research project.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None of the authors have any relevant conflict of interest or other financial disclosures.

Acknowledgments

Data availability statement

The National Vital Statistics System's mortality dataset are publicly available at the National Center for Health Statistics of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/index.htm).

Grant support

None.

Ethics Approval Statement and Patient Consent Statement

As the National Vital Statistic System dataset are completely de-identified and publicly available, this analysis per se was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

There was no material reproduced from other sources.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for disease control and prevention. US Dept of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2020. National diabetes statistics report; p. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy S.L., Xu J., Kochanek K.D., et al. Deaths: final data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66:1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim D., Li A.A., Cholankeril G., et al. Trends in overall, cardiovascular and cancer-related mortality among individuals with diabetes reported on death certificates in the United States between 2007 and 2017. Diabetologia. 2019;62:1185–1194. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4870-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zoppini G., Fedeli U., Gennaro N., et al. Mortality from chronic liver diseases in diabetes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1020–1025. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell P.T., Newton C.C., Patel A.V., et al. Diabetes and cause-specific mortality in a prospective cohort of one million U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1835–1844. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim D., Cholankeril G., Kim S.H., et al. Increasing mortality among patients with diabetes and chronic liver disease from 2007 to 2017. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:992–994. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available at: covid19.who.int/. Accessed on SEP 3rd, 2022.

- 8.Ahmad F.B., Cisewski J.A., Minino A., et al. Provisional mortality data - United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021. 2020;70:519–522. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7014e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim D., Li A.A., Gadiparthi C., et al. Changing trends in etiology-based annual mortality from chronic liver disease, from 2007 through 2016. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1154–1163. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.008. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim D., Li A.A., Perumpail B.J., et al. Changing trends in etiology-based and ethnicity-based annual mortality rates of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2019;69:1064–1074. doi: 10.1002/hep.30161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim D., Bonham C.A., Konyn P., et al. Mortality trends in chronic liver disease and cirrhosis in the united states, before and during COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.009. 2664-6 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mauvais-Jarvis F., Bairey Merz N., Barnes P.J., et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet. 2020;396:565–582. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lonardo A., Nascimbeni F., Ballestri S., et al. Sex differences in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: state of the art and identification of research gaps. Hepatology. 2019;70:1457–1469. doi: 10.1002/hep.30626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balakrishnan M., Patel P., Dunn-Valadez S., et al. Women have a lower risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease but a higher risk of progression vs men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.067. e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giovannucci E., Harlan D.M., Archer M.C., et al. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:207–221. doi: 10.3322/caac.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stepanova M., Clement S., Wong R., et al. Patients with diabetes and chronic liver disease are at increased risk for overall mortality: a population study from the United States. Clin Diabetes. 2017;35:79–83. doi: 10.2337/cd16-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cholankeril G., Goli K., Rana A., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on liver transplantation and alcohol-associated liver disease in the USA. Hepatology. 2021;74:3316–3329. doi: 10.1002/hep.32067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khubchandani J., Price J.H., Sharma S., et al. COVID-19 pandemic and weight gain in American adults: a nationwide population-based study. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2022;16 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2022.102392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milic J., Barbieri S., Gozzi L., et al. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease is highly prevalent in the postacute COVID syndrome. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac003. ofac003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerjee D., Reddy K.R. Review article: safety and tolerability of direct-acting anti-viral agents in the new era of hepatitis C therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:674–696. doi: 10.1111/apt.13514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The National Vital Statistics System's mortality dataset are publicly available at the National Center for Health Statistics of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/index.htm).