Abstract

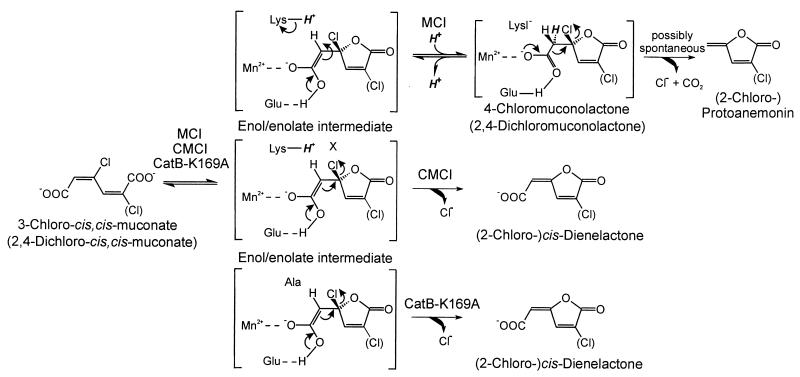

Chloromuconate cycloisomerases of bacteria utilizing chloroaromatic compounds are known to convert 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate to cis-dienelactone (cis-4-carboxymethylenebut-2-en-4-olide), while usual muconate cycloisomerases transform the same substrate to the bacteriotoxic protoanemonin. Formation of protoanemonin requires that the cycloisomerization of 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate to 4-chloromuconolactone is completed by protonation of the exocyclic carbon of the presumed enol/enolate intermediate before chloride elimination and decarboxylation take place to yield the final product. The formation of cis-dienelactone, in contrast, could occur either by dehydrohalogenation of 4-chloromuconolactone or, more directly, by chloride elimination from the enol/enolate intermediate. To reach a better understanding of the mechanisms of chloride elimination, the proton-donating Lys169 of Pseudomonas putida muconate cycloisomerase was changed to alanine. As expected, substrates requiring protonation, such as cis,cis-muconate as well as 2- and 3-methyl-, 3-fluoro-, and 2-chloro-cis,cis-muconate, were not converted at a significant rate by the K169A variant. However, the variant was still active with 3-chloro- and 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate. Interestingly, cis-dienelactone and 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone were formed as products, whereas the wild-type enzyme forms protoanemonin and the not previously isolated 2-chloroprotoanemonin, respectively. Thus, the chloromuconate cycloisomerases may avoid (chloro-)protoanemonin formation by increasing the rate of chloride abstraction from the enol/enolate intermediate compared to that of proton addition to it.

Chloroaromatic compounds, in general, tend to be relatively persistent to microbial degradation (13, 21). Nevertheless, some of these compounds can be mineralized by specialized bacteria, in many cases via ortho cleavage of chlorocatechol intermediates. Cycloisomerization of the chloro-cis,cis-muconates resulting from ring cleavage is a key reaction, because in chlorocatechol assimilating bacteria it is accompanied by dehalogenation (Fig. 1) (11, 12, 38).

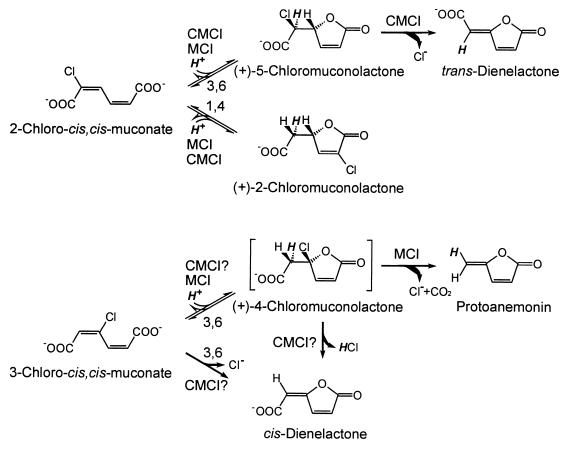

FIG. 1.

Reactions catalyzed by proteobacterial muconate cycloisomerases (MCI) and chloromuconate cycloisomerases (CMCI). Numbers on the arrows indicate whether the reaction is a 1,4- or a 3,6-cycloisomerization. “CMCI?” indicates that for chloromuconate cycloisomerases it is not clear whether cis-dienelactone is formed directly or via (+)-4-chloromuconolactone as intermediate. No attempt was made to differentiate between fast and slow turnover. The formation of chloromuconolactones involves the syn addition of a proton (bold italics) to the Cα atom.

For a long time, muconate cycloisomerases (EC 5.5.1.1) of catechol catabolic pathways and chloromuconate cycloisomerases (EC 5.5.1.7) of chlorocatechol degradative pathways were assumed to catalyze just the cycloisomerization reaction of, for example, 2-chloro- and 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate to 5-chloromuconolactone (4-carboxychloromethylbut-2-en-4-olide) and 4-chloromuconolactone (4-carboxymethyl-4-chlorobut-2-en-4-olide), respectively (34). Chloride elimination to trans-dienelactone and cis-dienelactone, respectively, was assumed to occur spontaneously in a secondary reaction. However, more recently Vollmer et al. (42) showed that proteobacterial muconate cycloisomerases form a pH-dependent equilibrium mixture of 2- and 5-chloromuconolactone from 2-chloro-cis,cis-muconate (Fig. 1), proving that these enzymes, in contrast to proteobacterial chloromuconate cycloisomerases, cannot cause dehalogenation during conversion of 2-chloro-cis,cis-muconate. Moreover, Blasco et al. (3) have shown that muconate cycloisomerases convert 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate predominantly to the antibiotic protoanemonin and not to cis-dienelactone as assumed before (34). Only for chloromuconate cycloisomerases has cis-dienelactone been shown to be the product (23, 34).

Blasco et al. (3) proposed that both muconate and chloromuconate cycloisomerases form 4-chloromuconolactone as an intermediate of 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate conversion. This would be further transformed in different ways by the two classes of enzymes. However, since the muconate and chloromuconate cycloisomerases catalyze syn additions to a double bond (2, 7), the α,β elimination of HCl from a 4-chloromuconolactone intermediate to yield cis-dienelactone would imply that exactly the same proton as added in the first part of the reaction would be removed in the second (33). Consequently, chloride had been assumed to be abstracted before a proton could be added to what was then regarded as an carbanion intermediate (25). Recent comparative studies on the reaction mechanisms of muconate cycloisomerase and mandelate racemase suggested that the intermediate to which a proton is added in the reaction with cis,cis-muconate is an enol/enolate and not a carbanion (15). Thus, one might assume that in the reaction of chloromuconate cycloisomerases with 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate, the corresponding enol/enolate intermediate is not protonated but rather loses the negative charge by chloride abstraction. The formation of protoanemonin in the reaction of muconate cycloisomerase with 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate, in contrast, should involve a protonation reaction, because two hydrogen atoms are present on the exocyclic carbon.

To test these hypotheses on the enzymatic reaction mechanism, the Lys169 residue of Pseudomonas putida muconate cycloisomerase and the Lys165 residue of the chloromuconate cycloisomerase TfdD of pJP4, which are known to provide the proton for the protonation reaction (15, 32), were changed to alanine, and the catalytic properties of the resulting enzyme variants (CatB-K169A and TfdD-K165A) were investigated with various substrates.

(Some of the results have been published in a preliminary communication [U. Schell and M. Schlömann, Bioengineering {special ed.} abstr. PF220, 1998].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and cultivation conditions.

Escherichia coli strain DH5α was purchased from GIBCO BRL. E. coli strain BL21(DE3,pLysS) (37) was used for gene expression under T7lac promoter control. Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid-containing strains were usually grown aerobically at 30 or 37°C with constant shaking in 2xYT medium (31) supplied with ampicillin (100 μg/ml). For growth on plates, Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (31) was supplemented with 1.5% (wt/vol) agar.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pBluescript II SK(+) | Phagemid derived from pUC19, lacZp, lacZ′, Apr, f1(+) and ColE1 origin | Stratagene; 1 |

| pBluescript II KS(+) | Same as pBluescript II SK(+) but with multiple cloning site in reverse orientation | Stratagene; 1 |

| pDCA11 | pUC20BM (Apr) with a 3.4-kb PstI-fragment from Ralstonia eutropha JMP134(pJP4) comprising tfdEFB′ | 41 |

| pTFDC1 | pRSET6a (Apr) with tfdC from R. eutropha JMP134(pJP4) flanked by NdeI and BamHI sites | 44 |

| pCATB1 | pET-11a* (Apr) with catB from P. putida PRS2000 flanked by NdeI and BamHI sites | 43 |

| pCATB7 | pBluescript II KS(+) (Apr) with 419-bp HindIII-SacII fragment of catB from pPX31 | M. D. Vollmer, unpublished results |

| pCATB8 | pCATB1 (Apr) with mutated 309-bp NotI-SacII fragment of catB; encodes CatB-K169A | This study |

| pTFDD1 | pRSET6a (Apr) with tfdD from R. eutropha JMP134(pJP4) flanked by NdeI and BamHI sites | 44 |

| pDCA7-1 | pBluescript II KS(+) (Apr) with 1.4-kb DraII-SacII fragment from R. eutropha JMP134(pJP4) comprising tfdC′DE′ | 44 |

| pTFDD2 | pBluescript II SK(+) (Apr) with 568-bp EagI-AccI fragment of tfdD from pDCA7-1 | This study |

| pTFDD15 | pTFDD1 (Apr) with mutated 568-bp EagI-AccI fragment of tfdD, encodes TfdD-K165A | This study |

Apr, resistance to ampicillin.

DNA preparation and in vitro manipulation.

Plasmid DNA was isolated by use of a Pharmacia FlexiPrep kit. Restriction endonuclease digests, ligations, and detection of colonies carrying an insert were performed according to standard procedures. DNA fragments were isolated from gels or purified in solution by use of a GeneClean II kit (Bio101, La Jolla, Calif.). Transformation of E. coli strains was achieved by the method of Inoue et al. (19).

PCR mutagenesis.

The CatB-K169A variant was generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis as described by Michael (24), using two outer amplification primers and one mutagenic phosphorylated oligonucleotide in one PCR. To avoid mutations other than the one desired, mutagenesis was carried out with pCATB7, which had been constructed earlier by cloning the 419-bp SacII-HindIII fragment of P. putida catB into pBluescript II KS(+) (M. D. Vollmer, unpublished results). The sequences of the two outer amplification primers were 5′-CTCGAAATTAACCCTCACTAAAG-3′ (BS_T3, directed toward the T3 promoter region of the vector) and 5′-AATTGTAATACGACTCACTATAG-3′ (BS_T7, reverse primer directed toward the T7 promoter region of the vector). Since these primers were originally designed for use with pBluescript and not pBluescript II, some 5′-terminal residues of the primers (bold) were not complementary to the template. To create the Lys (AAG) 169-to-Ala (GCG) mutation, a mutant oligonucleotide was derived for positions 491 to 515 of P. putida catB (EMBL/GenBank accession number U12557; 18, 43): 5′-GGGTGTTCAAGCTGGCGATTGGCG-3′ (M_K169A). The underlined nucleotides indicate where the changes were made to create the desired mutation. The melting temperature of the mutagenic oligonucleotide was chosen to be about 20°C higher than that of the outer primers to ensure a high mutagenesis efficiency. The mutagenic oligonucleotide was phosporylated by T4 polynucleotide kinase (GIBCO BRL) and then added directly to the amplification-mutagenesis reaction. The reaction mixture (50-μl total volume) consisted of 100 pmol of each of the three primers, 200 μM each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 5% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide, thermostable ligase buffer (25 mM potassium acetate, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 10 mM magnesium acetate, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM NAD+), 0.3 U of Goldstar DNA polymerase (Eurogentech), 20 U of Taq ligase (New England Biolabs), and 100 ng of XmnI-digested DNA of pCATB7 as the template. The thermocycling parameters were as follows: 29 cycles of denaturing (94°C, 30 s), annealing (60°C, 1 min), and polymerization-ligation (65°C, 4 min), with an additional 4.5 min of denaturing before addition of the polymerase and ligase during the first cycle and an additional 11 min of polymerization during the last cycle. As expected, this reaction yielded two products, a full-length product of about 530 bp and a smaller product of about 240 bp, the latter resulting from amplification between the mutagenic oligonucleotide and the BS_T7 primer annealing to the complementary strand. The full-length product was excised and isolated from an agarose gel, digested with NotI plus SacII, and after heat inactivation of both enzymes ligated into pBluescript II KS(+). After transformation into E. coli DH5α, clones with the expected 309-bp insert were checked by sequencing. One of three sequenced clones contained the mutation of interest. The mutated NotI-SacII-digested catB fragment was then cloned back into the 6.48-kb NotI-SacII fragment of pCATB1. The resulting construct, designated pCATB8, was checked by complete sequencing of its mutated catB insert.

An analogous substitution was introduced into the chloromuconate cycloisomerase gene tfdD from R. eutropha JMP134(pJP4). The site-directed TfdD-K165A variant was constructed by PCR using the same protocol as described above. The PCR template was pTFDD2, which carries the 568-bp EagI-AccI fragment of tfdD in pBluescript II SK(+). A mutant oligonucleotide was derived from nucleotide positions 480 to 505 of tfdD (EMBL/GenBank accession number M35097; 28) and designed to create the same substitution on DNA and protein sequence level as described above: 5′-TCGCTTCAAAGTCGCGCTTGGCTTCC-3′ (M_K165A). As expected, a full-length product of about 680 bp and a smaller product of about 190 bp were observed as PCR products. The full-length product was excised and eluted from an agarose gel, digested with EagI plus AccI, and purified again, since heat inactivation was not possible in this case. Ligation of the 568-bp fragment into pBluescript II SK(+) and subsequent transformation of E. coli DH5α yielded at least four clones with correctly sized inserts. One of these was checked by sequencing and confirmed to carry the correct mutation. The mutated EagI-AccI fragment was then cloned back into pTFDD1 which had been partially digested with EagI (27) and then further digested with AccI to yield the desired 3.29-kb pTFDD1 fragment. The complete, mutated tfdD insert of the resulting plasmid pTFDD15 was checked by sequencing.

Sequencing was performed on an automated ABI sequencer model 373 (Applied Biosystems) using an Applied Biosystems Prizm kit and the dye terminator cycle-sequencing protocol (AmpliTaq DNA polymerase; 25 cycles of 1 s at 98°C, 15 s at 60°C, and a final extension at 60°C for 4 min).

Enzyme assays.

Enzyme assays with chlorocatechol dioxygenase from R. eutropha JMP134 were performed as described by Schlömann et al. (33). Activities of cycloisomerases were assayed spectrophotometrically at 260 nm and 25°C by a modification of published procedures (26, 34), using 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM MnSO4, and 0.1 mM cis,cis-muconate or substituted cis,cis-muconates. If chloro-substituted substrates were used, dienelactone hydrolase of pJP4, partially purified by Q-Sepharose high-performance chromatography from an extract of E. coli DH5α(pDCA11), was provided in excess. The enzyme activity measurements were performed at least in duplicate. In general, extinction coefficients of substrates (9) were used for the calculation of activities. Coefficients for the conversion of 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate were chosen with respect to the products detected, using a coefficient of 5,800 M−1 cm−1, if the reaction proceeded via 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone to 2-chloromaleylacetate (23), or 4,300 M−1 cm−1, if the conversion proceeded to 2-chloroprotoanemonin (see Results). Correspondingly, a value of 12,400 M−1 cm−1 (9) was used when 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate was converted via cis-dienelactone to maleylacetate, and a value of 4,000 M−1 cm−1 (43) was used when protoanemonin was formed. Protein concentrations were calculated by the Bradford method (4), with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Enzyme expression and purification.

E. coli BL21(DE3,pLysS) was used as the host strain to express wild-type CatB from pCATB1 (43), CatB-K169A from pCATB8, and TfdD-K165A from pTFDD15. Growth and induction conditions were as described for overexpression of wild-type CatB (43) and wild-type TfdD (44), respectively. Cell harvesting, the preparation of extracts, and the enzyme purifications, in general, were performed as described by Vollmer et al. (43). The purification comprised an initial anion-exchange chromatography (Q Sepharose high-performance HR16/10) which was followed by hydrophobic interaction chromatography (Phenyl-Superose HR10/10). In the case of wild-type CatB, fractions with the highest specific activity with cis,cis-muconate eluted from the first column at ca. 0.16 M NaCl and from the second column at ca. 0.07 M (NH4)2SO4. In the case of CatB-K169A, activities with cis,cis-muconate, due to the mutation, were so low that assays would have required too much enzyme. Thus, those fractions which, as judged by reference to wild-type CatB, were expected to contain the variant CatB were checked for the presence of a 40-kDa band by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-gel electrophoresis (42) with subsequent Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 staining. Fractions with strongest 40-kDa bands eluted from the first column at ca. 0.18 M NaCl and from the second column at ca. 0.11 M (NH4)2SO4.

TfdD-K165A was purified from a 2-liter culture because expression of an R. eutropha gene from the pRSET6a vector proved to be not as effective as expression of a P. putida gene from pET11a* (43, 44). As with the CatB-K169A purification, the presence of overexpressed protein was checked only by SDS-gel electrophoresis since activities were very low. Fractions with the strongest 40-kDa bands eluted from the first column at ca. 0.37 M NaCl and from the second column at ca. 0.20 M (NH4)2SO4, similar to the wild-type enzyme (45).

The purity of the (chloro)muconate cycloisomerase preparations was analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue (see above). In the case of CatB, 21 mg of pure enzyme was obtained. The resulting preparations of CatB-K169A and TfdD-K165A contained 12 and 8.2 mg, respectively, of pure enzyme.

HPLC.

Substrates and products were quantified by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a SIL 100 C8 reversed-phase column (length, 250 mm; internal diameter, 4.6 mm; Grom, Herrenberg, Germany) protected by a LiChrospher RP8 precolumn (20 by 4.6 mm; Grom). Usually, samples of 10 μl were analyzed. The column effluent was monitored simultaneously at 210 and 260 nm by use of a variable-wavelength detector (Waters 490 programmable wavelength detector; Waters, Milford, Mass.). For analysis of products from cis,cis-muconate and 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate, 40% (wt/vol) methanol containing 0.1% (wt/vol) H3PO4 was used as the solvent at a flow rate of 0.7 ml min−1. Typical retention volumes were as follows: compound X (presumed reaction product of 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone and Tris), 3.0 ml; muconolactone, 3.2 ml; 2-chloromaleylacetic acid, 3.3 ml; 2-chloro-cis-acetylacrylic acid acylale, 3.8 ml; cis,cis-muconic acid and 2-chloro-trans-dienelactone, 4.4 ml; 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconic acid, 4.6 ml; 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconic acid and protoanemonin, 4.8 ml; 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone, 5.9 ml; and 2-chloroprotoanemonin, 6.3 ml. Since protoanemonin could not be separated well from 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconic acid under these conditions, 25% (wt/vol) methanol containing 0.1% (wt/vol) H3PO4 was used as the solvent for analysis of products from 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate turnover (flow rate, 0.9 ml min−1). Typical retention volumes were as follows: maleylacetic acid, 3.3 ml; cis-acetylacrylic acid acylale, 3.8 ml; trans-dienelactone, 4.4 ml; cis-dienelactone, 5.9 ml; protoanemonin, 6.4 ml; and 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconic acid, 7.4 ml.

For the preparation of 2-chloroprotoanemonin after conversion of 3,5-dichlorocatechol, a Grom SIL 100 C8 reversed-phase column of 125-mm length and 4.6-mm internal diameter was used with 40% (wt/vol) methanol without H3PO4 as the solvent and a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. Retention volumes were as follows: 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate, 1.2 ml; 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone, 1.6 ml; 2-chloroprotoanemonin, 3.2 ml; and 3,5-dichlorocatechol, 7.9 ml.

Preparation and identification of 2-chloroprotoanemonin.

The reaction mixture contained, in a final volume of 100 ml, 5 mmol of BisTris-HCl [bis-(2-hydroxyethyl)imino-tris(hydroxymethyl)methane-HCl) (pH 6.5), 0.2 mmol of MnSO4, 300 μmol of 3,5-dichlorocatechol, 24 U (measured with 3,5-dichlorocatechol) of chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase, provided as a cell extract of E. coli BL21(DE3,pLysS)(pTFDC1) (44), and 4,100 U (measured with cis,cis-muconate) of partially purified P. putida muconate cycloisomerase. 3,5-Dichlorocatechol (used as 20 mM stock solution) as well as muconate cycloisomerase were added stepwise during the conversion. The mixture was incubated at 25°C for 6 h and stirred slightly. The progress of the reaction was followed by HPLC analyses (for conditions, see above). After 6 h, a compound later identified as 2-chloroprotoanemonin was the major metabolite detected. Protein was removed at 4°C by ultrafiltration with an Amicon 8050 cell using a Diaflo ultrafiltration membrane (type PM10; Amicon). The preparation was extracted twice with 25 and 10 ml of diethyl ether. The combined organic phases were dried over Na2SO4, vaporized using a rotation evaporator (VV2000; Heidolph, Kelheim, Germany), and finally completely dried with an Alpha I-5 freeze-dryer (Christ, Osterode, Germany). Small amounts (5 to 10 mg) of a white substance which appeared to have a melting temperature between 0 and 10°C were obtained. High-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were obtained on a Bruker AC 250 spectrometer with the Pulse-Fourier transform technique and with nominal frequencies of 500.133 MHz for 1H NMR and 125.774 MHz for 13C NMR. The samples were dissolved in deuterated methanol, and tetramethylsilane was used as the internal standard. To estimate the extinction coefficient of 2-chloroprotoanemonin, the spectrum of a 0.1 mM solution was recorded between 200 and 400 nm on a double-beam spectrophotometer (Kontron Uvikon 941 Plus) against water as the background.

Preparation of a solution containing a 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone–Tris reaction product (compound X).

To check the absorption spectra of compound X under acidic and neutral conditions, the compound was prepared in a small scale by incubating a 0.5 mM 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone solution in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) at room temperature for 12 h, yielding X as the main product (at maximum, 82%). Upon acidification of 1 ml of this solution to pH 3.0, most of the by-product 2-chloromaleylacetate (16%), but not compound X, could be removed by extraction with the same volume of ethylacetate from the water phase. Compound X was therefore isolated from the latter by evaporation of the water under reduced pressure. Of the remaining pellet, 0.5 mg was dissolved in 2 ml of water, and the spectrum was recorded between 200 and 400 nm (see above). After acidification to pH 2.0 by addition of 1 μl of 85% H3PO4, a second spectrum was recorded.

Preparation of a solution containing the presumed 2-chloro-trans-dienelactone.

To provide an HPLC standard for experiments on 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate conversion, preparation of the presumed 2-chloro-trans-dienelactone from 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone (20) was attempted by UV irradiation at 254 nm in an analogous manner to the preparation of trans-dienelactone from cis-dienelactone (33) (Fig. 2). Irradiation was carried out at 4°C. A clear identification of 2-chloro-trans-dienelactone by NMR spectroscopy was not performed, because the final preparation contained large amounts of the cis isomer and further decay products (2-chloromaleylacetate and 2-chloro-cis-acetylacrylate). However, the correct assignment of this compound was supported by an E210/E260 nm ratio identical to that of 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone. Furthermore, the spectrum of the putative 2-chloro-trans-dienelactone, performed under stopped-flow conditions by HPLC, showed an absorption maximum at 282 nm similar to that of 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone (λmax = 283 nm [20]).

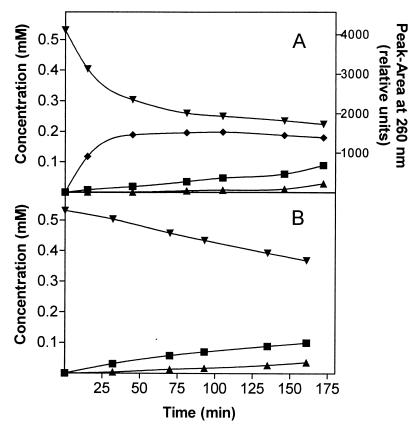

FIG. 2.

Preparation of 2-chloro-trans-dienelactone (⧫) under UV irradiation. An aqueous solution (1 ml) of 0.5 mM 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone (pH 5.0) (▾) was incubated at 4°C under a UV lamp as described by Schlömann et al. (33) (A). A control solution (1 ml) was incubated in the dark (B). 2-Chloromaleylacetic acid (■) and 2-chloro-cis-acetylacrylic acid (▴) were detected as minor by-products. For the presumed 2-chloro-trans-dienelactone, peak areas in relative units are given. A peak area of 910 relative units was assumed to be equivalent to 0.1 mM, since for each time point this would result in an overall concentration of all compounds detected of approximately 0.5 mM.

Chemicals.

Catechols and cis,cis-muconates, in general, were available from the same sources as described before (43). All other substituted cis,cis-muconic acids were synthesized enzymatically from the corresponding catechols, using cell extract from E. coli BL21(DE3,pLysS)(pTFDC1) (44). Protoanemonin was freshly prepared by converting 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate by large amounts of purified P. putida muconate cycloisomerase (3). trans-Dienelactone as well as cis-dienelactone and 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone were available from previous syntheses (17, 20, 30). Maleylacetate and 2-chloromaleylacetate were prepared from cis-dienelactone and 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone, respectively, by alkaline hydrolysis (11). trans-Acetylacrylic acid was purchased from Lancaster. cis-Acetylacrylic acid acylale was synthesized from maleylacetic acid under acidic conditions (33). In an analogous manner, 2-chloro-cis-acetylacrylic acid acylale was prepared from 0.25 mM 2-chloromaleylacetic acid by incubation for 120 min in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 3.0) (25°C). A product with the same retention volume was detected by heating an acidified solution of 2-chloromaleylacetic acid (ca. pH 4) at 95°C for 2.5 h. A product suggested to have been formed from 2-chloromaleylacetic acid by thermal decarboxylation and acidification was identified by Tiedje et al. (38) as 2-chloro-cis-acetylacrylic acid acylale.

RESULTS

Drastically reduced catalytic efficiency of muconate cycloisomerase variant K169A with most cis,cis-muconates.

Wild-type muconate cycloisomerase and the CatB-K169A variant were both purified to homogeneity as judged by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (single bands at ca. 40 kDa). CatB, purified 6.6-fold, gave a preparation with a specific activity of 224 U mg−1 measured with 0.1 mM cis,cis-muconate (Table 2). The purification of CatB-K169A was performed twice and yielded preparations with a specific activity of 0.003 U mg−1 or less (Table 2). The specific activity could be measured only by using 400 to 500 μg of enzyme in the assay and represented only 0.0015% or less of that of CatB, in accord with Lys169 being essential for the enzyme mechanism. By HPLC, muconolactone was shown to be formed by both CatB and CatB-K169A. CatB-K169A showed a residual activity with 0.1 mM 3-fluoro-cis,cis-muconate in the same order of magnitude as with cis,cis-muconate (0.001 U mg−1). When CatB-K169A was tested for conversion of 2-chloro-, 2-methyl-, and 3-methyl-cis,cis-muconate, specific activities were below the detection limit of 0.0005 U mg−1.

TABLE 2.

Activity of muconate cycloisomerase variant CatB-K169A with various substrates

| Substrate | Sp act with 0.1 mM substrate (U mg−1)a

|

Reduction of activityc (fold) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CatB wild type | CatB-K169Ab | ||

| cis,cis-Muconate | 224 | <0.0005–0.003 | 7 × 104 |

| 3-Fluoro-cis,cis-muconate | 110d | 0.001 | 11 × 104 |

| 3-Chloro-cis,cis-muconate | 3.4e | 0.010–0.011 | 310 |

| 2,4-Dichloro-cis,cis-muconate | 0.052f | 0.017–0.020g | 2.6 |

Assays with chloro-substituted substrates were performed in the presence of dienelactone hydrolase as auxiliary enzyme. Unless mentioned otherwise, the extinction coefficients of Dorn and Knackmuss (9) were used.

Where a range is given, the two activities were determined with two independently purified variant preparations.

The number given reflects the minimal value, i.e., the activity of the wild-type enzyme divided by the higher one of the values determined for the variant.

The specific activity with 3-fluoro-cis,cis-muconate was not measured directly but calculated from the activity with cis,cis-muconate by using kinetic data for the enzyme as determined by Vollmer et al. (43).

Δɛ = 4,000 M−1 cm−1 for the first 60 s (43).

Δɛ = 4,300 M−1 cm−1, determined as described in the text.

Δɛ = 5,800 M−1 cm−1 (23).

Conversion of 3-chloromuconate by P. putida muconate cycloisomerase and CatB-K169A.

When 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate conversion was followed by monitoring the extinction at 260 nm over at least 2 min in assays without auxiliary dienelactone hydrolase, a difference in product formation by CatB and CatB-K169A became obvious. An enzyme assay with CatB (0.6 U ml−1, measured with cis,cis-muconate) showed a decrease of E260 within the first ca. 20 s of measurement and then again an increase, indicating the formation of an intermediate with low absorption at 260 nm, presumably 4-chloromuconolactone, and a subsequent spontaneous or enzyme-catalyzed conversion of the latter to protoanemonin (λmax = 260 nm) (3). In contrast, an amount of CatB-K169A which corresponded to this experiment with respect to 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate conversion (only 0.002 U ml−1, measured with cis,cis-muconate) showed a continuous slight decrease but no increase of E260.

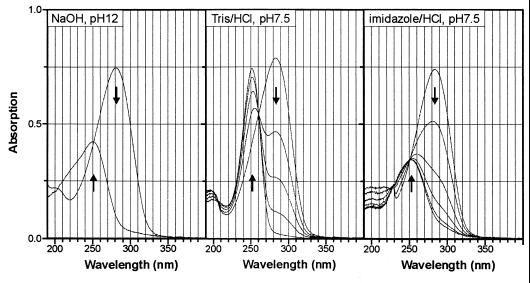

Conversion of 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate by CatB-K169A and CatB was subsequently investigated by running overlay UV spectra of enzyme assays and by analyses of products by HPLC (Fig. 3). When a 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate-containing reaction mixture was incubated with CatB, due to the relatively long cycle times between the spectra and because of similar absorbances of the substrate and the product protoanemonin, practically no absorbance changes occurred. With CatB-K169A, however, a strong shift toward 280 nm was observed. Monitoring of the CatB-K169A-catalyzed turnover by HPLC clearly showed the formation of a compound which cochromatographed with authentic cis-dienelactone.

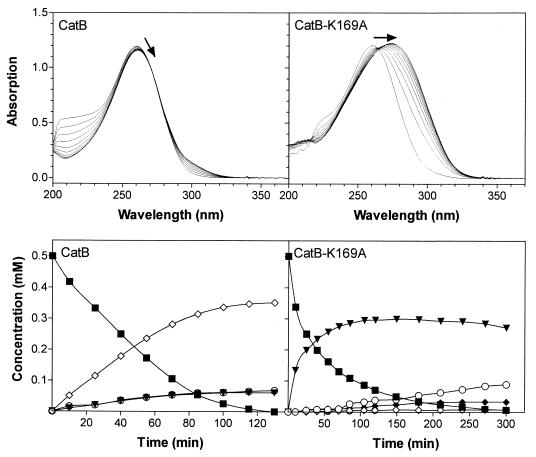

FIG. 3.

Conversion of 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate by wild-type CatB and CatB-K169A at pH 7.5. For overlay spectra, reaction mixtures (1 ml) contained 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM MnSO4, 0.1 mM 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate, and 0.001 to 0.002 U enzyme (measured with 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate). Reference cuvettes contained the same mixtures without substrate. Ten spectra were recorded at 25°C between 200 and 400 nm every 10 min, and at least 90% of the substrate was converted after the last cycle. Arrows indicate the shift of the absorption maximum. Product formation from 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate was additionally examined by HPLC analyses. Reaction conditions were the same as described above, except that 0.5 mM substrate was supplied and more enzyme was added (0.002 U of CatB and 0.007 U of CatB-K169A). 3-Chloro-cis,cis-muconate (■) was converted to cis-dienelactone (▾), maleylacetate (○), cis-acetylacrylate (⧫), and protoanemonin (◊). trans-Dienelactone was formed by CatB-K169A in concentrations no more than 0.014 mM (not shown).

Based on this knowledge, the specific activity of CatB with 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate was determined to be 3.4 U mg−1, using a Δɛ of 4,000 M−1 cm−1 for the reaction in the first 60 s (Table 2). The specific activity of CatB-K169A with 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate was estimated to be ca. 0.011 U mg−1, using an extinction coefficient of 12,400 M−1 cm−1 (Table 2). Thus, while the K169A mutation resulted in at least a 7 × 104-fold reduction of the reaction rate with cis,cis-muconate and in a ca. 11 × 104-fold reduction of the reaction rate with 3-fluoro-cis,cis-muconate, turnover of 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate was reduced only by a factor of 310 (Table 2).

Conversion of 2,4-dichloromuconate by CatB-K169A.

The conversion of 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate by CatB-K169A was likewise investigated by overlay UV spectra and HPLC measurements (Fig. 4, right). The peak maximum at 267 nm initially shifted toward 280 nm, and a new maximum subsequently appeared at about 254 nm. Monitoring of the CatB-K169A-catalyzed turnover by HPLC clearly showed the immediate formation of a compound which cochromatographed with authentic, i.e., chemically synthesized, 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone (λmax = 283 nm [20]). 2-Chloro-cis-dienelactone, however, proved to be relatively unstable at pH 7.5. Its concentrations never exceeded 30% of provided substrate.

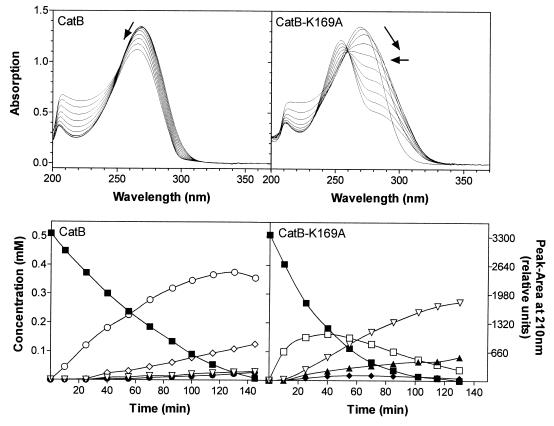

FIG. 4.

Conversion of 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate by wild-type CatB and CatB-K169A at pH 7.5. For overlay spectra, reaction mixtures (1 ml) contained 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM MnSO4, 0.1 mM 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate, and 0.001–0.002 U enzyme (measured with 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate). Reference cuvettes contained the same mixtures without substrate. Ten spectra were recorded as described in the legend to Fig. 3, and with both enzymes the substrate was completely converted after the last cycle. Arrows indicate the shift of the absorption maximum. For analysis of 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate turnover by HPLC, reaction conditions were the same as described above, except that 0.5 mM substrate was supplied and more enzyme was added (approximately 0.003 U). 2,4-Dichloro-cis,cis-muconate (■) was converted to 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone (□), 2-chloromaleylacetate (▴), 2-chloro-cis-acetylacrylate (●), 2-chloroprotoanemonin (○), 2-chloro-trans-dienelactone (⧫), a reaction product of 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone and Tris, i.e., compound X (▿), and the unknown compound Y (◊). For compounds X and Y, peak areas at 210 nm are given in relative units. From a preparation of compound X as described in Material and Methods, a peak area of 660 relative units was assumed to be equivalent to 0.1 mM.

The accumulation of a new compound X as the main product of 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate conversion could be shown to result from a nonenzymatic reaction of 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone. Stability experiments with 0.5 mM 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone in Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) (in the absence of enzyme) gave a product with the same UV spectrum and chromatographic behavior. Thus, a solution of X prepared from chemically synthesized 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone revealed different absorption spectra of X at neutral (λmax = 252 nm) and acidic (λmax = 229 nm) conditions. This corresponds well to the different absorption maxima of X from enzymatic 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate conversion as determined by HPLC under acidic, stopped-flow conditions (230 nm) or by overlay UV spectra at pH 7.5 (shift toward 254 nm [Fig. 4, right]). 2-Chloromaleylacetate and the presumed 2-chloro-trans-dienelactone appeared as minor by-products from nonenzymatic 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone conversion at pH 7.5.

Compound X is most probably a reaction product of 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone with Tris buffer. As illustrated by the UV spectra (Fig. 5), alkaline hydrolysis as well as hydrolysis of 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone in the presence of imidazole-HCl yielded 2-chloromaleylacetate (λmax = 250 nm, ɛ = 8,400 M−1 cm−1) as the product. In contrast, the reaction of 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone in the presence of Tris-HCl gave a product with a similar λmax but with a significantly higher molecular absorption coefficient (ɛ = 15,000 M−1 cm−1). In contrast to the products of alkaline- as well as imidazole-HCl-catalyzed hydrolysis, the product obtained with Tris showed no biological activity with maleylacetate reductase (data not shown). The fact that compound X occurred with Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) but not with imidazole-HCl (pH 7.5) as the buffer suggests that hydroxyl groups of the Tris buffer might be the reactive groups.

FIG. 5.

Formation of 2-chloromaleylacetate and compound X (a reaction product with Tris) during nonenzymatic turnover of 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone in aqueous NaOH and in the presence of different buffers, respectively. For alkaline hydrolysis, the reaction mixture (1 ml) contained 0.05 mM 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone in water. After recording the spectra using water as the reference, we added 2 μl of 2 M NaOH (4 μmol) to both cuvettes and recorded an overlay spectrum after 0.5 min. For the turnover in buffer, reaction mixtures (1 ml) contained 100 mM buffer and 0.05 mM 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone. Reference cuvettes contained the same buffer. Five spectra were recorded after 0.5, 8, 17, 30, and 60 min (Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) and after 0.5, 60, 120, 180, 240, and 270 min (imidazole-HCl, pH 7.5).

Since with respect to product formation from 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate, CatB-K169A resembled the chloromuconate cycloisomerases, the difference of extinction coefficients of substrate and product was assumed to be 5,800 M−1 cm−1 (23). With this Δɛ, values of up to 0.020 U mg−1 were determined for the specific activity of CatB-K169A with 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate (Table 2).

Conversion of 2,4-dichloromuconate by wild-type muconate cycloisomerase to 2-chloroprotoanemonin.

When a 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate-containing reaction mixture with CatB was followed by overlay UV spectra, the peak maximum first mainly decreased and then showed a gradual shift from 267 nm toward 250 nm (Fig. 4). This shift even continued for some time after the original substrate was completely converted. When following the CatB-catalyzed turnover of 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate by HPLC, we observed a product which had a retention volume only slightly different from that of 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone but differed significantly from the latter in having a higher relative absorption at 260 nm, compared to 210 nm. This compound could be easily extracted with diethyl ether under approximately neutral conditions and was identified as 2-chloroprotoanemonin (4-methylene-2-chlorobut-2-en-4-olide) (see below).

2-Chloroprotoanemonin proved to be considerably more stable at pH 6.5 (half-life of 11 h) than at pH 7.5 (half-life of <2 h). The by-products observed during 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate conversion at pH 7.5 (Fig. 4, left) included (i) the presumed 2-chloro-cis-acetylacrylate, (ii) a compound with the same retention volume and the same relative absorption at 210 and 260 nm as the presumed reaction product of 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone and Tris (compound X; see above), and (iii) a third, as yet unidentified compound Y eluting from the reversed-phase column between the latter two compounds. It thus had a retention volume similar to that of 2-chloromaleylacetic acid but differed from the latter in having a higher relative absorption at 260 nm, compared to 210 nm.

The Δɛ at 260 nm for formation of 2-chloroprotoanemonin from 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate was determined to be 4,300 M−1 cm−1. This value was determined by monitoring E260 during 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate conversion by 18 U of CatB (measured with cis,cis-muconate) in a 1-ml reaction mixture with dienelactone hydrolase and by correlating the ΔE260 to the difference in substrate concentrations as analyzed by HPLC prior to CatB addition and after 1.5 min. A specific activity of 0.052 U mg−1 was calculated for CatB with 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate (Table 2). Thus, the K169A mutation decreased the turnover rate of 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate by a factor of only 2.6, i.e., less than that of 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate and much less than that of cis,cis-muconate and other substituted muconates (Table 2).

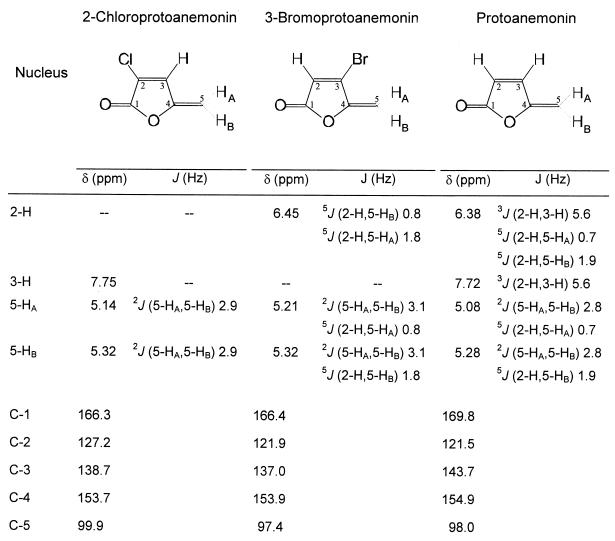

The product formed from 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate by muconate cycloisomerase was isolated as described in Materials and Methods. The 1H NMR spectrum (Fig. 6) showed three olefinic protons, centered at two different carbon atoms. One of the protons had a chemical shift value of 7.75 ppm, which is typical for the β proton in an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl system. This proton did not show any long-range coupling to 5-HA or 5-HB and was identified as 3-H. A geminal coupling of 2.9 Hz was observed between 5-HA and 5-HB. For the interpretation of 13C NMR spectra, it was useful to compare data with recently published data for 3-bromoprotoanemonin and protoanemonin (8). The most significant difference in chemical shifts of the carbon atoms is observed for C-2. The chlorine of 2-chloroprotoanemonin shifts the signal of C-2 around 5.5 ppm downfield compared to the C-2 signals of protoanemonin and 3-bromoprotoanemonin. The signals of C-3 of both 2-chloro- and 3-bromoprotoanemonin were shifted upfield in comparison to protoanemonin by 5 and 6.7 ppm, respectively. The λmax of an aqueous solution of 2-chloroprotoanemonin was determined to be 268 nm, and ɛ was 15,780 M−1 cm−1. These values were quite similar to those reported for protoanemonin (λmax = 260 nm; ɛ = 15,100 M−1 cm−1) (3).

FIG. 6.

1H NMR and 13C NMR data for different protoanemonins. The chemical shifts δ and the coupling constants J of 2-chloroprotoanemonin were determined with CD3OD as the solvent. 1H and 13C NMR data for 3-bromoprotoanemonin with CDCl3 as the solvent were taken from de March et al. (8). 1H NMR data for protoanemonin with CD3OD as the solvent were taken from Blasco et al. (3); 13C-NMR data with CDCl3 as the solvent were taken from de March et al. (8).

When 0.1 mM 2-chloroprotoanemonin dissolved in water was dropped on an LB plate which had been streaked with E. coli BL21(DE3,pLysS), overnight cell growth did not occur at the site of application. This preliminary experiment indicates that 2-chloroprotoanemonin, like protoanemonin, might be toxic for bacteria (3, 5, 35).

Inefficiency of TfdD-K165A with all tested cis,cis-muconates.

TfdD-K165A which was also purified to homogeneity gave specific activities below 0.001 U mg−1 with most cis,cis-muconates tested. 2,4-Dichloro-cis,cis-muconate was the only substrate still converted. A specific activity of 0.005 U mg−1 was measured with 0.1 mM substrate. From 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate, TfdD-K165A formed the same product as CatB-K169A, i.e., 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone.

DISCUSSION

As outlined in the introduction, we wanted to test the hypothesis that the formation of protoanemonin from 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate by muconate cycloisomerases requires enzymatic protonation of the respective enol/enolate intermediate, while the formation of cis-dienelactone from 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate by chloromuconate cycloisomerases should not necessitate a protonation, but instead chloride abstraction could take place. We thus changed the lysine that has been suggested to be responsible for protonation (15) to an alanine in both P. putida muconate cycloisomerase CatB and in the pJP4-encoded chloromuconate cycloisomerase TfdD.

We expected to find activity of the TfdD variant with those substrates which should not require protonation, i.e., 3-chloro- and 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate (29, 34). We also expected the CatB and the TfdD variants to be inactive toward substrates necessarily requiring protonation, like cis,cis-muconate (36), 2-chloro-cis,cis-muconate (42), 3-fluoro-cis,cis-muconate (33), and 2-methyl- and 3-methyl-cis,cis-muconate (6, 22). We were curious to see what the CatB variant would do with substrates which are obviously protonated by the wild-type enzyme, specifically 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate, and finally we wanted to investigate the product formation from 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate.

In contrast to our expectations, TfdD-K165A was completely inactive with 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate, and 2,4-dichloro-cis, cis-muconate conversion was also severely affected. The lack of any activity of TfdD-K165A with cis,cis-muconate or methylmuconates, on the other hand, was in accord with our expectations, as was the fact that the product formed from 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate was 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone. One might explain the inefficiency of this enzyme variant by the charge change of the active site. In analogy to CatB (16), the binding pocket of TfdD is probably positively charged and should be created by Mn2+ and the amino groups of Lys163 and Lys165. Upon replacement of Lys165 by a nonpolar alanine, the substrate which is negatively charged at pH 7 might bind less effectively. The K165A replacement could also have resulted in other unintended, structural changes which might negatively affect not only the protonation of the enol/enolate intermediate but also other steps of the cycloisomerization reaction.

In concordance with our expectations, CatB-K169A converted cis,cis-muconate and 3-fluoro-cis,cis-muconate about 105-fold slower than the wild-type enzyme (Table 2), while the activities with other substrates requiring protonation (methylmuconates and 2-chloro-cis,cis-muconate) were below the detection limit. At the same time, 3-chloro- and 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate were still converted at a considerable rate, thus proving that the almost complete inactivation of CatB observed with the other substrates was not due to some nonspecific effect as discussed above for TfdD-K165A. In fact, these observations provide experimental evidence for the inference from comparisons with mandelate racemase (15) and modeling studies on CatB (32) that Lys169 should be the protonating amino acid.

The most direct evidence for the validity of our basic hypothesis that protoanemonin formation from 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate should require a protonation step, whereas cis-dienelactone formation should not, came from the observed shifts of product formation: while wild-type CatB formed protoanemonin from 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate and 2-chloroprotoanemonin from 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate, the K169A variant formed cis-dienelactone and 2-chloro-cis-dienelactone, respectively (Fig. 7). Thus, a protonation reaction is definitely necessary for (chloro-)protoanemonin formation but not for (chloro-)cis-dienelactone formation.

FIG. 7.

Model for the mechanism of cycloisomerization and dehalogenation of 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate and 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate by proteobacterial muconate cycloisomerases (MCI), by chloromuconate cycloisomerases (CMCI), and by CatB-K169A. The proton provided by the active-site lysine is marked in bold italics. X indicates an active-site residue which might facilitate dehalogenation of the enol/enolate intermediate. Hypothetical intermediates are shown in brackets, with important active-site residues and Mn2+ included for the enzyme bound enol/enolate intermediate.

The findings just discussed cast a new light on the catalytic differences between muconate and chloromuconate cycloisomerases (Fig. 7). One might speculate that after the protonation of the (di-)chlorinated enol/enolate intermediate to 4-chloromuconolactone or 2,4-dichloromuconolactone, as catalyzed by muconate cycloisomerases, the decarboxylation and chloride elimination to (chloro-)protoanemonin occur as spontaneous, nonenzymatic reactions. Then the difference between muconate and chloromuconate cycloisomerases, with respect to product formation from 3-chloro- and 2,4-dichloro-cis,cis-muconate, would be due to the fact that of the competing possible reactions of the (di-)chlorinated enol/enolate, different ones are favored: protonation by Lys169 in case of the muconate cycloisomerases, and chloride elimination in case of the chloromuconate cycloisomerases.

It is not clear how this shift in favored reactions was accomplished during the divergence of the chloromuconate cycloisomerases from the muconate cycloisomerases. Obviously the evolutionary solution was different from our experimental one: the Lys169 of P. putida muconate cycloisomerase is conserved as Lys165 in the chloromuconate cycloisomerases of pJP4, pAC27, and pP51 (14, 28, 39) and as Lys168 in the chloromuconate cycloisomerase of Rhodococcus opacus 1CP (10). In principle, two possibilities exist: in chloromuconate cycloisomerases, (i) protonation of the (di-)chlorinated enol/enolate intermediate could be slowed down or (ii) chloride elimination could be accelerated. The former possibility appears to be less likely because the chloromuconate cycloisomerase TfdD converts 2- and 3-methyl-cis,cis-muconate to 3- and 4-methylmuconolactone almost as fast as the muconate cycloisomerase of P. putida converts cis,cis-muconate to muconolactone (43, 44). Thus, TfdD is fully capable of catalyzing a fast protonation. An enhanced rate of chloride elimination from the enol/enolate intermediate is therefore more probable.

In recent modeling studies with TfdD, a residue which could accelerate chloride elimination and which is in the correct position and geometry to the chlorine substituent has not yet been identified. At first sight, an active-site tryptophan appears to be a likely candidate (U. Schell, H.-J. Hecht, and M. Schlömann, unpublished data), because a chloride binding site comprising two tryptophan residues has also been found in haloalkane dehalogenase of Xanthobacter autotrophicus GJ10 (40). However, a replacement of Tyr59 in P. putida muconate cycloisomerase by tryptophan, the corresponding amino acid of chloromuconate cycloisomerase, did not avoid protoanemonin formation (43), nor did a reciprocal replacement of Trp55 in pJP4-encoded chloromuconate cycloisomerase by tyrosine abolish productive dehalogenation to dienelactones (Schell et al., unpublished). Thus, it remains to be elucidated which other amino acid residues are, in fact, responsible for (chloro-)cis-dienelactone formation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to H.-J. Knackmuss and to W. Reineke for providing excellent facilities and for stimulating discussions. We are also indebted to A. Goldman (Centre for Biotechnology, Turku, Finland) for advice on the mutation. For measuring the NMR spectra, we thank J. Rebell, Institute for Organic Chemistry and Isotope Research, University of Stuttgart. We also thank U. Riegert for support on the interpretation of NMR spectra. Thanks are due to R. Schmid (Institute for Technical Biochemistry, University of Stuttgart) for providing the facility for automated sequencing and to S. Lakner and S. Bürger for performing the sequencing.

This work was supported by a grant from the Federal Ministry of Research (project A10U; Zentrales Schwerpunktprojekt Bioverfahrenstechnik, Stuttgart, Germany).

Footnotes

Dedicated to Hans-Joachim Knackmuss on the occasion of his 65th birthday.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alting-Mees M A, Sorge J A, Short J M. pBluescript II: multifunctional cloning and mapping vectors. Methods Enzymol. 1992;216:483–495. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)16044-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avigad G, Englard S. Stereochemistry of enzymic reactions involved in cis,cis-muconic acid utilization. Fed Proc. 1969;28:345. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasco R, Wittich R-M, Mallavarapu M, Timmis K N, Pieper D H. From xenobiotic to antibiotic, formation of protoanemonin from 4-chlorocatechol by enzymes of the 3-oxoadipate pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29229–29235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caltrider P G. Protoanemonin. In: Corcoran J W, Hann F, editors. Antibiotics. 1. Mechanism of action. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1967. pp. 671–673. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catelani D, Fiecchi A, Galli E. (+)-γ-Carboxymethyl-γ-methyl-Δα-butenolide: a 1,2-ring-fission product of 4-methylcatechol by Pseudomonas desmolyticum. Biochem J. 1971;121:89–92. doi: 10.1042/bj1210089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chari R V J, Whitman C P, Kozarich J W, Ngai K-L, Ornston L N. Absolute stereochemical course of the 3-carboxymuconate cycloisomerases from Pseudomonas putida and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus: analysis and implications. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5514–5519. [Google Scholar]

- 8.de March P, Font J, Gracia A, Qingying Z. Easy access to 5-alkyl-4-bromo-2(5H)-furanones: synthesis of a fimbrolide, an acetoxyfimbrolide, and bromobeckerelide. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1814–1822. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorn E, Knackmuss H-J. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenated aromatic compounds. Substituent effects on the 1,2-dioxygenation of catechol. Biochem J. 1978;174:85–94. doi: 10.1042/bj1740085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eulberg D, Kourbatova E M, Golovleva L A, Schlömann M. Evolutionary relationship between chlorocatechol catabolic enzymes from Rhodococcus opacus 1CP and their counterparts in proteobacteria: sequence divergence and functional convergence. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1082–1094. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1082-1094.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans W C, Smith B S W, Moss P, Fernley H N. Bacterial metabolism of 4-chlorophenoxyacetate. Biochem J. 1971;122:509–517. doi: 10.1042/bj1220509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans W C, Smith B S W, Fernley H N, Davies J I. Bacterial metabolism of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate. Biochem J. 1971;122:543–551. doi: 10.1042/bj1220543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fewson C A. Biodegradation of xenobiotic and other persistent compounds: the causes of recalcitrance. Trends Biotechnol. 1988;6:148–153. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frantz B, Chakrabarty A M. Organization and nucleotide sequence determination of a gene cluster involved in 3-chlorocatechol degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4460–4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.13.4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerlt J A, Gassman P G. Understanding enzyme-catalyzed proton abstraction from carbon acids: details of stepwise mechanism for β-elimination reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:5928–5934. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helin S, Kahn P C, Lakshmi Guha Bh, Mallows D G, Goldman A. The refined X-ray structure of muconate lactonizing enzyme from Pseudomonas putida PRS2000 at 1.85Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:918–941. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinner I-S. Biochemische und molekularbiologische Untersuchungen zu Lacton-Hydrolasen des bakteriellen Aromaten- und Halogenaromaten-Abbaus. Diplomarbeit. Stuttgart, Germany: Universität Stuttgart; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houghton J E, Brown T M, Appel A J, Hughes E J, Ornston L N. Discontinuities in the evolution of Pseudomonas putida cat genes. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:401–412. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.2.401-412.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue H, Nojima H, Okayama H. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene. 1990;96:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90336-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaschabek S R. Chemische Synthese von Metaboliten des mikrobiellen Chloraromatenabbaus und Untersuchung der Substratspezifität der Maleylacetat-Reduktase aus Pseudomonas sp. Stamm B13. Ph.D. thesis. Wuppertal, Germany: Bergische Universität—Gesamthochschule Wuppertal; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knackmuss H-J. Degradation of halogenated and sulfonated hydrocarbons. In: Leisinger T, Hütter R, Cook A M, Nüesch J, editors. Microbial degradation of xenobiotics and recalcitrant compounds. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knackmuss H-J, Hellwig M, Lackner H, Otting W. Cometabolism of 3-methylbenzoate and methylcatechols by a 3-chlorobenzoate utilizing Pseudomonas: accumulation of (+)-2,5-dihydro-4-methyl- and (+)-2,5-dihydro-2-methyl-5-oxofuran-2-acetic acid. Eur J Appl Microbiol. 1976;2:267–276. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhm A E, Schlömann M, Knackmuss H-J, Pieper D H. Purification and characterization of dichloromuconate cycloisomerase from Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP134. Biochem J. 1990;266:877–883. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michael S F. Mutagenesis by incorporation of a phosphorylated oligo during PCR amplification. BioTechniques. 1994;16:410–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ngai K-L, Kallen R G. Enzymes of the β-ketoadipate pathway in Pseudomonas putida: primary and secondary kinetic and equilibrium deuterium isotope effects upon the interconversion of (+)-muconolactone to cis,cis-muconate catalyzed by cis,cis-muconate cycloisomerase. Biochemistry. 1983;22:5231–5236. doi: 10.1021/bi00291a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ornston L N. The conversion of catechol and protocatechuate to β-ketoadipate by Pseudomonas putida. III. Enzymes of the catechol pathway. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:3795–3799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perbal B. A practical guide to molecular cloning. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Interscience, John Wiley & Sons; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perkins E J, Gordon M P, Caceres O, Lurquin P F. Organization and sequence analysis of the 2,4-dichlorophenol hydroxylase and dichlorocatechol oxidative operons of plasmid pJP4. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2351–2359. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2351-2359.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pieper D H, Kuhm A E, Stadler-Fritzsche K, Fischer P, Knackmuss H-J. Metabolism of 3,5-dichlorocatechol by Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP134. Arch Microbiol. 1991;156:218–222. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reineke W, Knackmuss H-J. Microbial metabolism of haloaromatics: isolation and properties of a chlorobenzene-degrading bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:395–402. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.2.395-402.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schell U, Helin S, Kajander T, Schlömann M, Goldman A. Structural basis for the activity of two muconate cycloisomerase variants towards substituted muconates. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1999;34:125–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlömann M, Fischer P, Schmidt E, Knackmuss H-J. Enzymatic formation, stability, and spontaneous reactions of 4-fluoromuconolactone, a metabolite of the bacterial degradation of 4-fluorobenzoate. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5119–5129. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5119-5129.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt E, Knackmuss H-J. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenated aromatic compounds. Conversion of chlorinated muconic acids into maleoylacetic acid. Biochem J. 1980;192:339–347. doi: 10.1042/bj1920339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seegal B C, Holden M. The antibiotic activity of extracts of Ranunculaceae. Science. 1945;101:413–414. doi: 10.1126/science.101.2625.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sistrom W R, Stanier R Y. The mechanism of formation of β-ketoadipic acid by bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1954;210:821–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tiedje J M, Duxbury J M, Alexander M, Dawson J E. 2,4-D metabolism: pathway of degradation of chlorocatechols by Arthrobacter sp. J Agric Food Chem. 1969;17:1021–1026. doi: 10.1021/jf60165a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Meer J R, Eggen R I L, Zehnder A J B, de Vos W M. Sequence analysis of the Pseudomonas sp. strain P51 tcb gene cluster, which encodes metabolism of chlorinated catechols: evidence for specialization of catechol 1,2-dioxygenases for chlorinated substrates. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2425–2434. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2425-2434.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verschueren K H G, Kingma J, Rozeboom H J, Kalk K H, Janssen D B, Dijkstra B W. Crystallographic studies of the interaction of haloalkane dehalogenase with halide ions. Studies with halide compounds reveal a halide binding site in the active site. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9031–9037. doi: 10.1021/bi00086a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vollmer M D. Alcaligenes eutrophus Stamm JMP134. Diplomarbeit. Stuttgart, Germany: Universität Stuttgart; 1992. Untersuchungen zur Dehalogenierung im Dichloraromatenabbau in. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vollmer M D, Fischer P, Knackmuss H-J, Schlömann M. Inability of muconate cycloisomerases to cause dehalogenation during conversion of 2-chloro-cis,cis-muconate. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4366–4375. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.14.4366-4375.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vollmer M D, Hoier H, Hecht H-J, Schell U, Gröning J, Goldman A, Schlömann M. Substrate specificity and product formation by muconate cycloisomerases: an analysis of wild-type enzymes and engineered variants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3290–3299. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3290-3299.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vollmer M D, Schell U, Seibert V, Schlömann M. Substrate specificities of the chloromuconate cycloisomerases from Pseudomonas sp. B13, Ralstonia eutropha JMP134 and Pseudomonas sp. P51 and implications for enzyme evolution. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;51:598–605. doi: 10.1007/s002530051438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vollmer M D, Schlömann M. Conversion of 2-chloro-cis,cis-muconate and its metabolites 2-chloro- and 5-chloromuconolactone by chloromuconate cycloisomerases of pJP4 and pAC27. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2938–2941. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2938-2941.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]