ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

The COVID‐19 pandemic has caused interruptions to the K‐12 US school landscape since spring 2020.

METHODS

In summer 2020, we completed a pilot study utilizing interviews (n = 13) with school staff (ie, nurses, educators) from across the United States. We aimed to understand the status of school operation and re‐entry plans after the primary period of school closure, along with resources needed for students and staff during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

RESULTS

All interviewees described their school's re‐entry plan as complete or in‐development. Ten plans included strategies to meet students' mental health needs. Only 3 clearly planned for staff mental health resources. Interviews suggest gaps in planning and execution of mental health resources for school staff, a group already vulnerable to stress, anxiety, and burnout.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH

Several school staff mental health resources were developed as a result of the pandemic, though ongoing impacts necessitate integration of these supports into school operation plans. This is particularly important as schools continue to navigate periods of altered operation in response to elevated community COVID‐19 infection rates.

CONCLUSIONS

As schools implement strategies to support students, similar consideration should be given to the adults in the school environment who teach and support school‐aged children.

Keywords: COVID‐19, mental health, school health, staff wellness

INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic forced unexpected, widespread closures of K‐12 school buildings in the United States in the spring of 2020. As schools scrambled to identify mechanisms for minimizing the negative effect on learning and essential academic services in the 2019/20020 school year, it became clear that the pandemic would impact traditional schooling for years to come. Specifically, schools must now prepare and plan for different models of operation, including full in person, virtual, and hybrid models while having the capacity to rapidly transition between these models. 1

In the summer of 2020, our team conducted a national survey of over 7000 school staff in partnership with the American School Health Association (ASHA) regarding plans for school reopening. 2 Respondents indicated a primary focus on physical challenges presented by the pandemic (eg, social distancing). While administrators weigh operational models, including the physical safety of school professionals and students, along with the potential impact on academic outcomes, there is a delicate balance between promoting the safety of students, teachers, and their families, while considering the unforeseen side effects of the pandemic on mental health. 3 , 4 Additional literature describes family challenges related to food insecurity, increasing suicide rates, and social isolation. 5 , 6 Less is available, however, on the impact of COVID‐19 on the mental wellness of school staff. Initial reports indicate similar concerns for school staff to what is being documented in children. 7 , 8 , 9 Negative mental health impacts on school staff doing their best to provide continuity in teaching and support for their students in unprecedented circumstances deserves further exploration.

Prompted by Pattison et al.'s 2 aforementioned survey results, we conducted a pilot study utilizing interviews with school staff across the United States to better understand their school's operational response to the COVID‐19 pandemic, specifically, structure and resources to support staff mental wellness.

METHODS

Participants

Members of ASHA (n = 7467) were invited to participate in an anonymous survey study to identify initial impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on school wellness initiatives in June 2020. 2 Participants were asked to provide their contact information for participation in follow‐up interviews. These individuals (n = 102) were contacted via recruitment email and invited to complete an eligibility screening survey, resulting in 29 eligible respondents. Eligibility criteria ensured potential participants could speak and read English, were at least 18 years old, and were employed by a traditional school district within the United States as of March 15, 2020. Thirteen school staff participated in semi‐structured interviews between July and September 2020.

Procedures and Instrumentation

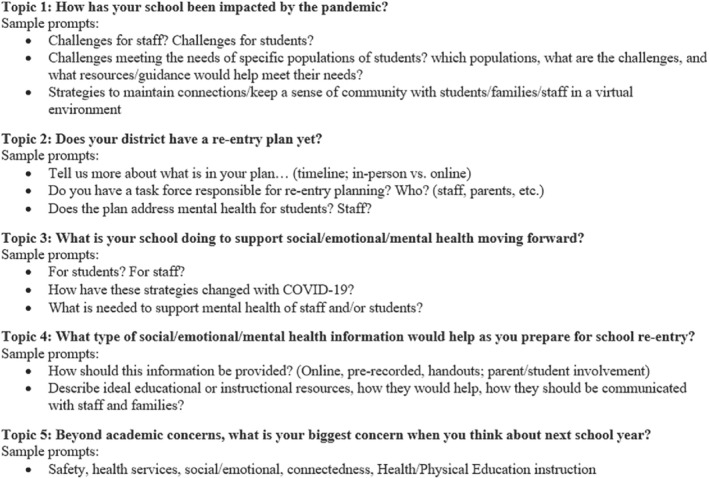

Demographic data was captured via a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) survey. REDCap is a secure, web‐based platform used for data collection purposes by researchers, hosted at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and Penn State College of Medicine. Thirty‐minute interviews were scheduled based on the participant's availability and conducted through a web‐based meeting platform for audio recording. Two interviewers followed a semi‐structured interview guide developed by the study team. The interview guide expanded upon closed‐ended questions included in previously conducted survey study. Questions focused on the development of school re‐entry plans and included content, along with resources planned for supporting the social/emotional health of students and staff. Figure 1 displays topics in the semi‐structured interview guide. Upon completion of all interviews, a professional service transcribed the interview recordings.

Figure 1.

Topics and Prompts Used in Interviews With School Staff

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using descriptive content analysis and quantitative content analysis. Two coders independently coded 20% of the transcripts using a codebook derived from the interview guide within NVIVO 12 software. The codebook was revised based on the independent coding results. When a reliable Kappa score was attained (K = .9), the 2 coders divided the remaining transcripts and coded independently. This standard process saved time, reduced bias, and ensured both coders interpreted and applied the codebook consistently.

RESULTS

Participants (n = 13) were predominantly white (100%) females (92%) with advanced degrees (54%) and represented public schools across 12 states (Table 1). The participants represented elementary schools (n = 1), middle/high schools (n = 5), and a combination of levels and/or whole districts (n = 7). Represented schools were located across varying locales (Table 1). All 13 participants reported their school closed to in‐person instruction in spring 2020.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics (n = 13)

| Age | Mean = 50.2 |

| Median = 53 | |

| Gender | Male = 1 |

| Female = 12 | |

| Race | White = 13 |

| Highest degree | Bachelor's = 6 |

| Master's = 6 | |

| Doctoral = 1 | |

| School locale | Rural = 5 |

| Suburban = 6 | |

| Urban = 2 | |

| Professional role | Nurse = 7 |

| School mental health provider = 2 | |

| Educator = 3 | |

| Food service professional = 1 | |

| States represented | Alaska, Arizona, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, Tennessee, Wisconsin (n = 2) |

School Re‐Entry Plans

Participants provided information about the development of their school's re‐entry plan and activities, with all 13 indicating their plan was complete or in‐development. Ten (77%) reported their school was including planning for student mental health activities, where only 3 interviewees (23%) described planning for school staff mental health topics.

New Social/Emotional Health Strategies as a Result of COVID‐19 Focused on Students

Interviewees described plans for new strategies to address the social and emotional (SE) health of students during the 2020/2021 school year. Several described back‐to‐school procedures, such as “… the first week is going to be a lot of letting them understand expectations, and helping them work through fears and worries about being at school” (Participant 27) and that schools were “… spending a lot of time on the ‘getting to know you’ activities … checking in on them, making sure that they're okay mentally, that they don't need any support at home” (Participant 87). In addition, some schools focused on addressing SE knowledge: “The district has provided us with a week's worth of social‐emotional lessons based on grade level that we are to do live over the internet” (Participant 87). Several others described dedicated time in the school day for “an activity of some sort; …team building…mindfulness, something like that” (Participant 41). One interviewee described a survey to parents to better understand each family's needs related to school nursing, counseling, and other types of assistance.

Notably, participants described far fewer strategies for the social and emotional health of school staff. Limited examples included “webinars and things like that, videos you could watch … supposed to help take down your level of stress and anxiety” (Participant 3).

School Staff Are Experiencing High Levels of Stress and Anxiety

Throughout the interviews, school staff consistently shared concerns about staff stress and anxiety. One participant summarized her biggest concern as “… the stress on teachers and just kind of how this is going to impact teachers” (Participant 6). They also described the negative impacts of virtual learning environments, stating, “It's going to make it harder to deliver services, and to teach them to be mindful of everything at once, and to have to worry about all of this on their plate, in addition to everything else that teachers normally face …” (Participant 6).

Resources Are Needed to Support School Staff

Respondents shared information about resources that may be most beneficial to address the high levels of stress and anxiety of school staff. In general, the requests centered around administration simply checking in to show they care and also by having a “… [Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child] team that's well coordinated and empowered … [where] you can address the health of everybody in the school, including the staff” (Participant 52). More specifically, they requested materials, such as handouts, and videos that can be used independently and on their own time. Several also identified a need for networking and connection to others where they could share experiences and concerns.

Additional requests highlighted needs related to employee assistance program resources that would connect staff with social workers, counselors, or psychologists, “someone who is working with the district, but may not necessarily work for the district” (Participant 3).

DISCUSSION

Interviews with school staff between July and September 2020 revealed each school had a complete or in‐development re‐entry operations plan. Ten of the plans including strategies to meet students' mental health needs, but only 3 intentionally planned for staff mental health resources. Pattison et al.'s survey, 2 which prompted the school staff interviews, highlighted that needs such as student and staff mental health would become a priority once COVID protocols, including procurement of personal protective equipment and safety protocols, were well‐established. At the time of the interviews, schools had started creating and implementing social and emotional resources for students, but support for school staff mental health was lagging.

The COVID‐19 pandemic forced teachers to find meaningful ways to teach and connect with students and their families. 10 , 11 Coupled with trying to develop new strategies and skills, teachers were also at home experiencing social isolation. 12 Initial reports indicate similar negative mental health concerns for teachers and other school professionals to those documented in children. 7 , 8 A lack of staff resources has continued for a population already experiencing mental health concerns including stress, anxiety, and burnout. 7 Similarly, in our study, school staff reported limited examples of social and emotional staff activities.

Interview findings support research from Spain, where a high percentage of teachers demonstrated anxiety, depression, and stress symptoms due to the pandemic. School staff surveyed raised concerns that their own well‐being had been ignored during the re‐opening phase and called for the Spanish government to address staff anxiety. 7 Researchers in the United States have also called on employers, health care systems and public health agencies to improve the mental health and overall well‐being among employees. 13 Similar responses were expressed through our interviews as participants shared examples of limited action on the part of school administrators and highlighted requests to connect with social workers, counselors, or psychologists outside of the district.

As we approach the 2‐year mark of the pandemic, schools and their staff and students are still navigating an unstable environment marked with weekly changes in national‐level recommendations and reports of new variants. This unfortunately requires the conversation to change from “what do you need to get through this” to “how do we navigate the new normal.” As such, we conclude this manuscript with several resources developed to meet the ongoing wellness needs of school staff.

The state of Wisconsin has created the Compassion Resilience Toolkit, which includes ready‐made materials for supporting individual and organizational wellness and self‐care (https://compassionresiliencetoolkit.org/). Their school toolkit combines suggestions from classroom teachers, student services staff, administrative leaders, and community mental health practitioners. It is designed to promote teacher resiliency, decrease burnout and attrition in the face of challenging environments and situations. The Pennsylvania Department of Education released the Staff and Student Wellness Guide that is designed to highlight components that should be considered in school‐level wellness planning. 14 In addition, the University of Maryland School of Medicine's National Center for School Mental Health (NCSMH) has a repository of data collection instruments and wellness resources for school staff and administrators (www.schoolmentalhealth.org).

Finally, as 1 participant noted, there is value in constructing a response to the identified needs within the context of the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child model (WSCC). 15 The WSCC model prioritizes the connection between health and academics and recognizes the importance and impact of wellness among school staff. Schools considering how to meet the needs of students and staff, while managing limited financial and human capital, may consider adopting change that aligns with the WSCC model for the greatest impact. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offer guidance on implementation through their Healthy Schools websites. 16

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. While the study sample included representatives of schools across the United States, they were identified through their affiliation with the American School Health Association and may not be representative of all schools. Also, self‐reported data regarding school re‐opening procedures and plans were unable to be verified.

Conclusions

Data described in this study indicate that schools continue to exist at different stages of planning and implementation of not only social‐emotional supports for students and staff, but also COVID‐19 response and navigation processes. Though, schools were more apt to develop plans to address the social and emotional needs of students during COVID‐19‐induced school changes than their staff. The guides and resources referenced include components to support student and staff wellness regardless of where school entities are in managing the ebb and flow of COVID‐19 infection rates and resulting shifts between in‐person to remote learning operations.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH

COVID‐19 has unequivocally changed the landscape of schools in both academic and school health arenas. As schools consider and implement strategies to support their students both physically and mentally, similar consideration should be given to the adults in the school environment who serve as leaders, role models, educators, confidants, nurturers, and countless other important roles to school‐aged children. Schools should continue to strive toward alignment with the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child model, especially in times of change. Plans to address overall school social and emotional climates should be specific in the inclusion of strategies and resources for school staff, as well. Meeting the needs of school staff should begin with the awareness, training, and utilization of resources that are currently available, and highlighted in this manuscript.

Human Subjects Approval Statement

This study was approved by the Pennsylvania State University IRB and all participants gave their implied consent to participate.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Hoke AM, Pattison KL, Molinari A, Allen K, Sekhar DL. Insights on COVID‐19, school reopening procedures, and mental wellness: pilot interviews with school employees. J Sch Health. 2022; 92: 1040‐1044. DOI: 10.1111/josh.13241

Funding for data analysis was received, in part, through Children's Miracle Network at Penn State Health Children's Hospital. The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1 TR002014 and Grant UL1 TR00045. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Thank you to the American School Health Association members that participated in the interviews and shared their perspectives during a time of unprecedented challenges.

Contributor Information

Alicia M. Hoke, Email: ahoke1@pennstatehealth.psu.edu.

Krista L. Pattison, Email: kpattison@pennstatehealth.psu.edu.

Alissa Molinari, Email: amolinari@pennstatehealth.psu.edu.

Kathleen Allen, Email: kallen1@pennstatehealth.psu.edu.

Deepa L. Sekhar, Email: dsekhar@pennstatehealth.psu.edu.

References

- 1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Reopening K‐12 Schools During the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Prioritizing Health, Equity, and Communities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2020. 10.17226/25858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pattison KL, Hoke AM, Schaefer EW, Alter J, Sekhar DL. National Survey of School Employees: COVID‐19, school reopening, and student wellness. J Sch Health. 2021;91(5):376‐383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sharfstein JM, Morphew CC. The urgency and challenge of opening K‐12 schools in the fall of 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(2):133‐134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Viner RM, Bonell C, Drake L, et al. Reopening schools during the COVID‐19 pandemic: governments must balance the uncertainty and risks of reopening schools against the clear harms associated with prolonged closure. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106(2):111‐113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Larsen L, Helland MS, Holt T. The impact of school closure and social isolation on children in vulnerable families during COVID‐19: a focus on children's reactions. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;31:1‐11. 10.1007/s00787-021-01758-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xiang M, Zhang Z, Kuwahara K. Impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on children and adolescents' lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(4):531‐532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marchant E, Todd C, James M, Crick T, Dwyer R, Brophy S. Primary school staff perspectives of school closures due to COVID‐19, experiences of schools reopening and recommendations for the future: a qualitative survey in Wales. PLoS One. 2021;16(12):e0260396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Evanoff BA, Strickland JR, Dale AM, et al. Correction: work‐related and personal factors associated with mental well‐being during the COVID‐19 response: survey of health care and other workers. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(4):e29069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cardoza K. (Host)‘We need to be nurtured, too’: many teachers say they're reaching a breaking point [audio podcast transcript]. In: All Things Considered. Washington, DC: NPR; 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/04/19/988211478/we‐need‐to‐be‐nurtured‐too‐many‐teachers‐say‐theyre‐reaching‐a‐breaking‐point. [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeWitt, P. (2020). 6 reasons students aren't showing up for virtual learning. Education Week's Blogs. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion‐6‐reasons‐students‐arent‐showing‐up‐for‐virtual‐learning/2020/04

- 11. Merrill, S. (2020). Teaching through a pandemic: A mindset for this moment. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/article/teaching‐through‐pandemic‐mindset‐moment

- 12. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912‐920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaden U. COVID‐19 school closure‐related changes to the professional life of a K‐12 teacher. Educ Sci. 2020;10(6):165. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pennsylvania Department of Education . Staff and Student Wellness Guide; 2020. Available at: https://www.education.pa.gov/Schools/safeschools/emergencyplanning/COVID‐19/SchoolReopeningGuidance/ReopeningPreKto12/CreatingEquitableSchoolSystems/Pages/Support‐Social‐and‐Emotional‐Wellness.aspx. Accessed February 4, 2022.

- 15. Lewallen TC, Hunt H, Potts‐Datema W, Zaza S, Giles W. The whole school, whole community, whole child model: a new approach for improving educational attainment and healthy development for students. J Sch Health. 2015;85(11):729‐739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC); 2021. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/wscc/index.htm. Accessed February 4, 2022.