Abstract

Introduction

The leading cause of death for women is cardiovascular disease (CVD), including ischaemic heart disease, stroke and heart failure. Previous literature suggests peer support interventions improve self-reported recovery, hope and empowerment in other patient populations, but the evidence for peer support interventions in women with CVD is unknown. The aim of this study is to describe peer support interventions for women with CVD using an evidence map. Specific objectives are to: (1) provide an overview of peer support interventions used in women with ischaemic heart disease, stroke and heart failure, (2) identify gaps in primary studies where new or better studies are needed and (3) describe knowledge gaps where complete systematic reviews are required.

Methods and analysis

We are building on previous experience and expertise in knowledge synthesis using methods described by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information (EPPI) and the Coordinating Centre at the Institute of Education. Seven databases will be searched from inception: CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, APA PsycINFO, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Scopus. We will also conduct grey literature searches for registered clinical trials, dissertations and theses, and conference abstracts. Inclusion and exclusion criteria will be kept broad, and studies will be included if they discuss a peer support intervention and include women, independent of the research design. No date or language limits will be applied to the searches. Qualitative findings will be summarised narratively, and quantitative analyses will be performed using R.

Ethics and dissemination

The University of Toronto’s Research Ethics Board granted approval on 28 April 2022 (Protocol #42608). Bubble plots (ie, weighted scatter plots), geographical heat/choropleth maps and infographics will be used to illustrate peer support intervention elements by category of CVD. Knowledge dissemination will include publication, presentation/public forums and social media.

Keywords: Heart failure, Ischaemic heart disease, Stroke

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Publication bias will be mitigated by including sources of evidence written in both English and French, and by performing targeted searches for relevant grey literature.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria will be kept broad and studies will be included if they discuss a peer support intervention and include women (cis and trans) with ischaemic heart disease, stroke or heart failure, independent of the research design.

All team members will receive 1 hour of training on screening titles and abstracts, 1 hour of training on screening full-text reviews and 2 hours of training on data extraction.

Bubble plots (ie, weighted scatter plots), geographical heat/choropleth maps and infographics will be used to graphically illustrate quantitative results.

Although the individual and family self-management theory will consider the broader context of gender and outcomes, a conceptual theory that foregrounds gender within an intersectional lens may have strengthened study methods and results.

Introduction

The leading cause of premature death for women is cardiovascular disease (CVD), responsible for 35% of total deaths in 2019.1 Ischaemic heart disease (IHD), stroke and heart failure are the most common causes of mortality,1 2 which vary across the lifespan and are influenced by ethnicity, racism and gender.3 4 Globally, mortality rates have remained stagnant; however, in 2017, mortality increased in women in two high income countries: Canada and the USA.1 Young women are now more likely to die within 1 year of a myocardial infarction (MI) compared with men,5 6 and women who are transgender have a greater than twofold increase in MI compared with women who are cisgender.7 Moreover, most women are unaware of risk factors or symptoms.8 Women also have depression,9 anxiety9 10 and lower health-related quality of life (HRQoL)11 1 year after an MI and for many women, fear and anxiety about the future and difficulty moving forward in recovery extends beyond 5 years of having an MI.12–14 Stroke is the second most common cause of CVD mortality in women worldwide.15 Getahun et al16 also demonstrated an increased risk of stroke in transgender women. Women have a higher lifetime stroke risk compared with men,1 with risk being highest during pregnancy, menopause and later in life.17 Women with heart failure tend to have preserved ejection fraction, peripartum cardiomyopathy and/or Takotsubo syndrome,18 19 and there are few to no treatments for specific heart failure phenotypes in women,1 causing more depression and impaired HRQoL in women compared with men.20 21

International CVD priorities, led by the WHO’s Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (2013–2020) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (2015–2030), focus on good health, gender equality, innovation and infrastructure, reduced inequalities, and partnerships.22 Good health focuses on ensuring healthy lives and promoting the well-being of all people at all ages, with a focus to reduce premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and the promotion of mental health and well-being.22 Individuals 43–70 years with IHD report worse physical HRQoL (38.9 (95% CI 36.9 to 41.0)) compared with the general population.23 Similar results are reported in women with obstructive (41.9, SD 8.9) and non-obstructive heart disease (43.7, SD 9.4) (p=0.072).24 Moreover, a decline in physical vs mental HRQoL is more predictive of hospital readmission25 and mortality in healthy middle-aged and older women (n=40 337)26 and in men and women with heart disease.25 The World Heart Federation has been advocating globally for better CVD outcomes, suggesting advocacy tactics and strategies to reduce CVD by 25% by 2025.22 This includes addressing behavioural risk factors for better prevention and reducing IHD and stroke in women by identifying and aligning with national CVD priorities, strategic communications, media engagement, evidence-based research, partnership development and collaborating with key decision-makers.22 The Lancet Commission advocates for a global imperative to reduce the global burden of CVD in women by 2030.1

Social support in the form of relationships with family and friends, as well as peer support from other women with CVD, has been identified as an integral component in the recovery process for women following a cardiac event.27 Perceived social support has a direct impact on health outcomes; individuals with low levels of social support have higher CVD-related28 and all-cause mortality rates.29 Results from the Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI Patients study suggested lower social support was associated with worse health outcomes and more depressive symptoms 12 months after an MI, with one in five individuals less than 55 years of age having low social support following an MI.30 Others report that individuals with low social support following an MI had more angina (relative risk, 1.27; 95% CI 1.10 to 1.48), lower HRQoL (mean difference (β) = −3.33; 95% CI −5.25 to –1.41), lower mental functioning (β=−1.72; 95% CI −2.65 to –0.79) and more depressive symptoms (β=0.94; 95% CI 0.51 to 1.38).31 Moreover, the association between social support and HRQoL, depression and physical functioning appears to be stronger in women compared with men.31 In the general population, twice as many women have depression32 33 and anxiety34 35 as men, which are known risk factors for CVD. Depressive symptoms are associated with atherosclerotic IHD (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.13, per one-point increase in the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) score) and death (adjusted HR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.14, per one-point increase in the PHQ-9 score) in women younger than 55 years, but not in men or in women over 55 years.36 In postmenopausal women, fatal cardiac events are associated with depression.37 Anxiety has also been linked to developing and the worsening IHD and CVD mortality.38

It has been suggested that social support, specifically from other women who have lived a similar health or recovery experience, may play a key role in women’s CVD rehabilitation and recovery.8 39 40 Peer support is the provision of assistance and encouragement by an individual that is considered equal41; it is a form of social support delivered by a layperson who has received some formal training to share experiential knowledge and emotional assistance. Defining attributes of all peer relationships include emotional, informational and appraisal support.41 Moreover, providing and receiving support benefits both the receiver and the provider of support.42 Women (n=387) aged 42±6 years who received a peer support intervention reported better cardiovascular risk factor profiles (ie, hypertension, exercise, weight and smoking) compared with women randomised to a control group (difference: 0.75; 95% CI 0.32 to 1.18).43 In patients and caregivers following a stroke, the value of peer support during the recovery process was derived through information and advice, encouragement and empowerment, awareness, being helpful and making connections.44 There is some evidence that peer support interventions improve self-reported recovery for individuals with CVD,45 46 and hope and empowerment in other patient populations that include those with mental illness, HIV and women who are breast feeding.47–49 Women have identified the importance of engagement in several different activities to promote their recovery including behavioural, social and psychological dimensions.27 As individuals focus on their own recovery in the context of multiple social roles, re-evaluation and reprioritisation of self can be a challenging task. Women face unique challenges in managing their health and modifying their lifestyle during recovery.50–53 Women often prioritise family, household responsibilities and caregiver tasks, which subsequently place preventive health behaviours and their own health status as secondary.54 There is a need to distinctly enhance the nature and level of care provided to women living with CVD. Although there is some evidence for the beneficial effects of peer support in women with CVD, a more gender-informative and culturally sensitive knowledge synthesis across the lifespan is needed.

Objectives

The overall aim of this study is to describe peer support interventions for women with CVD (IHD, stroke and heart failure) using an evidence map. Specific objectives are to: (1) provide an overview of peer support interventions used in women with IHD, stroke and heart failure, (2) identify gaps in primary studies where new or better studies are needed and (3) describe knowledge gaps where complete systematic reviews are required.

Methods and analysis

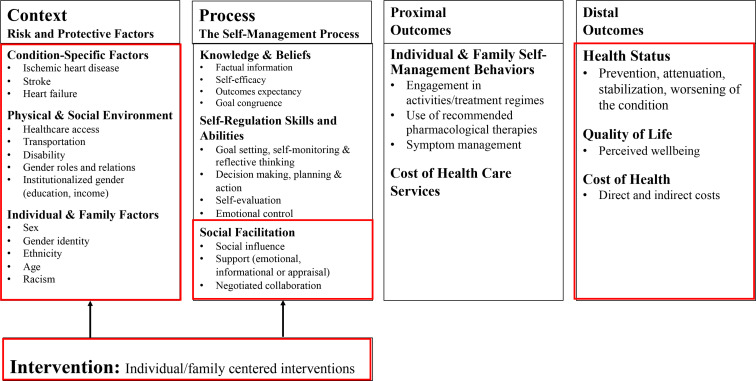

The main purpose of performing a broad map of the literature (ie, evidence map) is to identify the range of research and identify gaps and future research needs.55 An evidence map is broad in scope, but systematic in its approach to synthesise the evidence.55 Evidence mapping is useful in directing future research, including systematic reviews.56 57 We are collaborating with women with lived experience (Goodenough, Robert) and the Canadian Women’s Heart Health Alliance (CWHHA) and using the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Capacity Development Framework,58 SPOR Patient Engagement Framework59 and the Individual and Family Self-Management Theory60 61 to describe peer support interventions used for women with CVD (IHD, stroke, heart failure). The individual and family self-management theory61 consists of three dimensions: context, process and outcomes. We have used this in a previous integrated mixed methods systematic review to guide processes related to defining patient-reported outcome variables and variables used for data extraction.62 This theory depicts self-management within the broader context of people and other influences (eg, ethnicity, racism, healthcare access and institutionalised gender).63 The individual and family self-management Theory61 has provided a platform for testing clinical interventions that have included the Arthritis Self-Management Programme64 and the Diabetes Self-Management Programme.65 This model highlights the role of social influence (eg, peer support) and the value of emotional, informational and appraisal support (figure 1).61 66

Figure 1.

Individual and family self-management theory model.

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Protocols 2015 checklist when preparing this manuscript (online supplemental table 1).67 In addition, the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public-Long Form (GRIPP 2-LF) was used to document the engagement of women with lived experience (online supplemental table 2).68 We will also use a patient partner compensation rate structure described in the Recommendations on Patient Engagement Compensation—Prepared by the SPOR Networks in Chronic Diseases and the PICHI Network69: each woman with lived experience will receive a 1-year honorarium of US$1000 that will include compensation for 4 hours of training and assistance across all other activities of the project (ie, screening, knowledge translation and exchange activities).

bmjopen-2022-067812supp001.pdf (167KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-067812supp002.pdf (68KB, pdf)

We will not register our evidence map on PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews, as evidence mapping does not meet the inclusion criteria for this registry. However, to manage records and promote transparency, we have registered our project on the Open Science Framework (DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/E7KQ3).70 Assessment of risk of bias, meta-bias(es) or strength of the evidence will not be undertaken. We will follow methods described by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information (EPPI) and the Coordinating Centre at the Institute of Education,57 71–74 using six steps used in performing previous broad maps of the literature75: (1) identify the scope of the evidence map, (2) define key variables, (3) establish a comprehensive search strategy, (4) identify clear eligibility criteria, (5) systematically retrieve, screen and classify the evidence and (6) report the findings in an evidence map.

Identify the scope of the evidence map

The initial scope of the work was defined by the research team to focus on the most common causes of CVD mortality in women1 2: IHD, stroke and heart failure. The research question, key variables and eligibility criteria were discussed with women with lived experience (Goodenough, Robert). Our overarching review question was established: What is known about peer support interventions used for women with CVD (IHD, stroke, and heart failure)? This question can be answered by a broad range of evidence that includes randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort and cross-sectional studies, case–control studies and case series/reports across reported from urban and rural settings across the globe.

Define key variables

We used the PICO framework to focus our research question and also to inform our broad search of the literature.76 The PICO elements included the population, intervention, comparison and outcomes. Keywords and the National Library of Medicine’s Medical Subject Headings were combined under two of the PICO categories: (P) women with CVD (IHD, stroke and heart failure) and (I) peer support. We did not search using a comparator or by outcome so that we could maintain breadth and reduce bias in our search strategy. Women with lived experience (Goodenough, Robert) collaborated to identify and confirm search terms as there is evidence that this may increase the number of citations retrieved by 34%.55 77 The draft MEDLINE search strategy (table 1) was also informed by searches of existing reviews78 79 and executed by a library scientist (Visintini).

Table 1.

Draft MEDLINE search, 1946 (database: MEDLINE(R) ALL, Platform: Ovid)

| # | Searches |

| 1 | *social support/ |

| 2 | Self-Help Groups/ |

| 3 | peer group/ |

| 4 | (peer* adj3 (support* or educat*)).ti, ab, kf. |

| 5 | ((social adj3 support) and peer*).ti, ab, kf. |

| 6 | or/1–5 |

| 7 | ((heart or cardiac) adj2 (disease or surg* or patient?)).ti, ab, kf. |

| 8 | exp Myocardial Ischemia/ |

| 9 | ((coronary adj2 (arter* or stenos* or atheroscleros* or arterioscleros* or syndrome or microvascular)) or (coronary adj5 disease?) or CAD).ti, ab, kf. |

| 10 | (small adj2 (arter* or vessel*) adj2 disease*).ti, ab, kf. |

| 11 | (angina or stroke? or MINOCA or INOCA or SCAD or Kounis).ti, ab, kf. |

| 12 | ((heart or myocardial) adj3 infarct*).ti, ab, kf. |

| 13 | (isch?emi* adj3 (heart or cardiac or myocardial)).ti, ab, kf. |

| 14 | ((heart or cardiac or coronary) adj2 (spasm* or vasospasm* or embolism*)).ti, ab, kf. |

| 15 | exp Myocardial Revascularization/ |

| 16 | (((aortocoronary or coronary) adj3 bypass*) or CABG).ti, ab, kf. |

| 17 | (angioplast* or atherectom* or endarterectom* or thrombectom* or PCI or PTCA or (Percutaneous adj3 (intervent* or revascular*))).ti, ab, kf. |

| 18 | exp Stroke/ |

| 19 | Stroke Rehabilitation/ |

| 20 | Cardiac Rehabilitation/ |

| 21 | ((brain* or cerebr* or cerebell* or vertebrobasilar or hemispher* or intracran* or intracerebral* or infratentorial* or supratentorial* or anterior circulation or posterior circulation or basal ganglia) adj5 (isch?emi* or infarct* or thrombo* or emboli*)).ti, ab, kf. |

| 22 | ((brain* or cerebr* or cerebell* or intracerebral or intracran* or parenchymal or intraventricular or infratentorial or supratentorial or basal gangli*) adj5 (h?emorrhage* or h?ematoma* or bleed*)).ti, ab, kf. |

| 23 | exp Heart Failure/ |

| 24 | exp Ventricular Dysfunction, Left/ |

| 25 | ((heart or cardiac) adj2 (failure or resynchroni*)).ti, ab, kf. |

| 26 | (cardiomyopath* or Takotsubo or HFrEF or HFpEF).ti, ab, kf. |

| 27 | or/7–26 |

| 28 | 6 and 27 |

Establish a comprehensive search strategy

The literature on peer support interventions used for women with CVD (IHD, stroke and heart failure) will be systematically and comprehensively searched using subject headings and keywords in accordance with the search syntaxes in each bibliographic databases. As noted, the search was drafted in MEDLINE via Ovid (table 1) by a library scientist. Prior to finalisation and execution, the draft MEDLINE search strategy will be peer reviewed by another librarian.80 It will then be translated and run from inception in the remaining databases: CINAHL (EBSCO), EMBASE (Ovid), APA PsycINFO (Ovid), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Ovid) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Ovid) and Scopus (www.scopus.com). We will also search Clinicaltrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. Further grey literature will be identified via Proquest Dissertations and Theses, handsearching abstracts for specific conferences, and a targeted advanced Google search. No date or language limits will be applied to the searches. Citations will be exported from electronic search interfaces to Covidence81 for duplicate elimination and screening.

Identify clear eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria will be kept broad, and studies will be included if they discuss a peer support intervention and include women, independent of the research design (table 2). Types of participants will include cis and trans women greater than 18 years of age with IHD, stroke or heart failure. To ensure our search is broad, we will not specifically search by ‘women’. However, we will ensure women are included in the studies during the screening process. We will not specifically define a minimum sample size of women to minimise selection bias. Moreover, this will be an important variable to describe in our evidence map. Outcomes will include health status, HRQoL and healthcare costs. We will include disease-specific and generic reports and measures of two patient-reported outcomes: health status (ie, worsening of the condition) and HRQoL (ie, perceived well-being measured using the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, 12-item short form survey (SF-12), EQ 5D value health instrument).82 Estimating direct and indirect costs of peer support using a cost-effectiveness analysis, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio or quality-adjusted life-years will be included.83

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Include if study involves | Exclude if study involves |

Women

Adults aged 18 and older One or more of the following diagnoses:

A support intervention led by a peer(s)

|

Men only Exclusively the following diagnoses (if none of the inclusion diagnoses on the left are also present):

Support programmes led by healthcare professionals, and not peers with lived experience Informal social support from family, friends, or caregivers, and not peers with lived experience Systematic reviews and meta-analyses, scoping reviews (these types of studies should be flagged and documented in a group Google doc for reference) Descriptive or qualitative papers presenting general principles, frameworks, conceptual models or qualities of peer support, but that do not evaluate a peer support intervention(s), specifically (these types of studies might be useful to flag in our Google doc as reference papers) |

Systematically retrieve, screen and classify the evidence

All team members, including women with lived experience, will participate in retrieving, screening and classifying the evidence. All team members will receive: (1) 1 hour of training on screening titles and abstracts, (2) 1 hour of training on screening full-text reviews and (3) 2 hours of training on data extraction (4 hours total). A test batch of studies (n=24) screened as ‘include, exclude or unsure’ will be compared for inter-rater reliability and discussed between reviewers (including the women with lived experience (Goodenough, Robert)) in a 2-hour meeting to establish title and abstract screening accuracy and confirm understanding of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.84 Title, abstract and full-text articles will be screened by two independent reviewers. Disagreements or conflicts will be resolved by a third reviewer (Parry or Mullen). Data from included studies will be extracted to include article-level data (eg, author/country, publication year) and study-level data (eg, sample size, percent women, study design, population (eg, context), intervention and outcomes). Contextual factors will include participant characteristics as guided by the individual and family self-management theory (eg, sex, gender (roles, relations, identity and institutionalised), ethnicity, racism, age).61 We will use the Template for Intervention Description and Replication85 to extract peer support intervention details that will include intervention procedures, peer background and training, modes of delivery (ie, face to face, group), location of delivery (ie, in-person, virtual), number of times the intervention was delivered over what period of time (ie, duration, intensity, dose) and intervention fidelity. Social facilitation details including type of support (emotional, informational and appraisal support) will also be captured in our data extraction. Outcomes will include health status, HRQoL and healthcare costs. To ensure transparency and rigour, we will describe our methods of locating relevant unpublished and grey literature in a systematic way,72 86 87 following processes used in our previous broad map of the literature.75

Report findings in an evidence map

The findings of all studies meeting the eligibility criteria will summarised narratively. This will include a description of the participants, settings and peer support interventions. The individual and family self-management theory will guide specific descriptions by context, process and outcomes. Bubble plots (ie, weighted scatter plots), geographical heat/choropleth maps and infographics will be used to graphically illustrate peer support intervention elements by category of CVD (ie, IHD, stroke and heart failure). Analyses will be performed using R, a software environment for statistical computing and graphics.88

Patient and public involvement

Two women living with CVD (Goodenough, Robert) are members of our investigative team and members of the CWHHA, a volunteer organisation of over 130 health professionals and women living with CVD. The mission of the CWHHA is to support patients, clinicians, scientists and decision-makers to implement evidence, transform clinical practices and impact public policy related to women’s cardiovascular health. CWHHA members, and the 16 patient advocate members, voted in the Fall 2020 strategic planning session to pursue a project focused on peer support for women with CVD. This evidence map review is direct guidance from women who live with CVD. We are using the SPOR Capacity Development Framework58 and the SPOR Patient Engagement Framework59 to ensure the perspectives of women living with CVD are integrated into all steps of this broad map of the literature, including developing the research question/objectives, key variables, and eligibility criteria, defining search terms, screening titles/abstracts and full text papers, evaluating results and disseminating findings. The GRIPP 2-LF68 has been used to document patient engagement activities and we have used the patient partner compensation rate structure described in the Recommendations on Patient Engagement Compensation-Prepared by the SPOR Networks in Chronic Diseases and the PICHI Network.69 The guiding principles of cobuild, inclusiveness, support and mutual respect underpin all patient engagement activities in this study.59

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval has been granted from the University of Toronto (42608, 28 April 2022). It is not necessary to obtain informed consent for this review. Knowledge will be disseminated through publication, presentation/public forums and social media.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @parryresearch, @NajahAdreak

Contributors: The PI (MP) and Co-PI (K-AM) conceived the study. DK and MP drafted and revised the manuscript prior to submission. Coauthors (NA, TC, SD, ZG, CG, JH, AJ, DK, KL, SL, K-AM, MN, AO’H, HR, NT and SV) will contribute to all steps of the review. One coauthor (AW) will be responsible for coordinating administrative aspects of the review. Most authors (NA, TC, SD, CG, JH, AJ, DK, KL, SL, K-AM, MN, MP, HR, NT, SV) are grant holders. We thank the two women with lived experience (CG, HR) from the CWHHA who are Co-Is. MP finalised the Research Ethic Board (REB) submission. The Co-PIs (MP, K-AM) will provide day-to-day oversight of the review. Most authors (NA, TC, SD, CG, JH, AJ, DK, KL, SL, K-AM, MN, MP, HR, NT, SV) assisted to build and approve content for the funding application. All authors (NA, TC, TD, ZG, CG, JH, AJ, DK, KL, SL, K-AM, MN, AO’H, MP, HR, NT, SV, AW) approved the final manuscript prior to submission. All authors (NA, TC, SD, CG, JH, AJ, DK, KL, SL, K-AM, MN, AO’H, MP, HR, NT, SV, AW) are also accountable for all aspects of ensuring the accuracy and integrity of the work across all steps of the review.

Funding: This work was supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Patient-Oriented Research-open pool Priority Announcement (CIHR; 470800).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Vogel B, Acevedo M, Appelman Y, et al. The Lancet women and cardiovascular disease Commission: reducing the global burden by 2030. Lancet 2021;397:2385–438. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00684-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norris CM, Yip CYY, Nerenberg KA, et al. Introducing the Canadian women's heart health alliance atlas on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of cardiovascular diseases in women. CJC Open 2020;2:145–50. 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norris CM, Yip CYY, Nerenberg KA, et al. State of the science in women's cardiovascular disease: a Canadian perspective on the influence of sex and gender. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e015634. 10.1161/JAHA.119.015634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverman-Lloyd LG, Bishop NS, Cerdeña JP. Race is not a risk factor: Reframing discourse on racial health inequities in CVD prevention. Am J Prev Cardiol 2021;6:100185. 10.1016/j.ajpc.2021.100185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaffer S, Foulds H, Grewal J. Canadian Women’s Heart Health Alliance Atlas. Chapter 2: The Scope of the Problem. CJC Open 2021;3:1–11. 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Izadnegahdar M, Singer J, Lee MK, et al. Do younger women fare worse? sex differences in acute myocardial infarction hospitalization and early mortality rates over ten years. J Womens Health 2014;23:10–17. 10.1089/jwh.2013.4507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alzahrani T, Nguyen T, Ryan A, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors and myocardial infarction in the transgender population. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2019;12:e005597. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonnell LA, Pipe AL, Westcott C, et al. Perceived vs actual knowledge and risk of heart disease in women: findings from a Canadian survey on heart health awareness, attitudes, and lifestyle. Can J Cardiol 2014;30:827–34. 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norris CM, Hegadoren KM, Patterson L, et al. Sex differences in prodromal symptoms of patients with acute coronary syndrome: a pilot study. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs 2008;23:27–31. 10.1111/j.1751-7117.2008.08010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon T, Lim LL, Powell H, et al. Psychosocial experiences of cardiac patients in early recovery: a community-based study. J Adv Nurs 2000;31:1368–75. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacey EA, Walters SJ. Continuing inequality: gender and social class influences on self perceived health after a heart attack. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:622–7. 10.1136/jech.57.8.622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sjöström-Strand A, Ivarsson B, Sjöberg T. Women's experience of a myocardial infarction: 5 years later. Scand J Caring Sci 2011;25:459–66. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00849.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liblik K, Hu R, Gomes Z, et al. Female risk factors for post-myocardial infarction depression and anxiety (FRIDA): pilot results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2022;78:138–40. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2022.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liblik K, Mulvagh SL, Hindmarch CCT, et al. Depression and anxiety following acute myocardial infarction in women. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2022;32:341–7. 10.1016/j.tcm.2021.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators . Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2015;385:117–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Getahun D, Nash R, Flanders WD, et al. Cross-sex hormones and acute cardiovascular events in transgender persons: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:205–10. 10.7326/M17-2785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cordonnier C, Sprigg N, Sandset EC, et al. Stroke in women - from evidence to inequalities. Nat Rev Neurol 2017;13:521–32. 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2018 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation 2018;137:e67–492. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam CSP, Arnott C, Beale AL, et al. Sex differences in heart failure. Eur Heart J 2019;40:3859–68. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, et al. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:1527–37. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khariton Y, Nassif ME, Thomas L, et al. Health status disparities by sex, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in outpatients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:465–73. 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markbreiter J, Buckley P. CVD advocacy toolkit; 2016.

- 23.Prior JA, Jordan KP, Kadam UT. Variations in patient-reported physical health between cardiac and musculoskeletal diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:71. 10.1186/s12955-015-0265-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rieckmann N, Neumann K, Feger S, et al. Health-related qualify of life, angina type and coronary artery disease in patients with stable chest pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2020;18:140. 10.1186/s12955-020-01312-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen TB, Thygesen LC, Zwisler AD, et al. Self-reported health-related quality of life predicts 5-year mortality and hospital readmissions in patients with ischaemic heart disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015;22:882–9. 10.1177/2047487314535682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Adler N, et al. Prospective change in health-related quality of life and subsequent mortality among middle-aged and older women. Am J Public Health 2008;98:2085–91. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colella TJF, Hardy M, Hart D, et al. The Canadian women's heart health alliance atlas on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of cardiovascular disease in women-chapter 3: patient perspectives. CJC Open 2021;3:229–35. 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barth J, Schneider S, von Känel R. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2010;72:229–38. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d01611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000316. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bucholz EM, Strait KM, Dreyer RP, et al. Effect of low perceived social support on health outcomes in young patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the VIRGO (variation in recovery: role of gender on outcomes of young AMI patients) study. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e001252. 10.1161/JAHA.114.001252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leifheit-Limson EC, Reid KJ, Kasl SV, et al. The role of social support in health status and depressive symptoms after acute myocardial infarction. Circ: Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:143–50. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.899815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carrero JJ, de Jager DJ, Verduijn M, et al. Cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality among men and women starting dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:1722–30. 10.2215/CJN.11331210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albert PR. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015;40:219–21. 10.1503/jpn.150205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mallik S, Spertus JA, Reid KJ, et al. Depressive symptoms after acute myocardial infarction: evidence for highest rates in younger women. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:876–83. 10.1001/archinte.166.8.876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meijer A, Conradi HJ, Bos EH, et al. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of 25 years of research. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011;33:203–16. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shah AJ, Ghasemzadeh N, Zaragoza-Macias E, et al. Sex and age differences in the association of depression with obstructive coronary artery disease and adverse cardiovascular events. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000741. 10.1161/JAHA.113.000741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaccarino V, Badimon L, Corti R, et al. Ischaemic heart disease in women: are there sex differences in pathophysiology and risk factors? Position paper from the working group on coronary pathophysiology and microcirculation of the European Society of cardiology. Cardiovasc Res 2011;90:9–17. 10.1093/cvr/cvq394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roest AM, Martens EJ, de Jonge P, et al. Anxiety and risk of incident coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:38–46. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arthur HM, Wright DM, Smith KM. Women and heart disease: the treatment may end but the suffering continues. Can J Nurs Res 2001;33:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kristofferzon M-L, Löfmark R, Carlsson M. Myocardial infarction: gender differences in coping and social support. J Adv Nurs 2003;44:360–74. 10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02815.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dennis C-L. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2003;40:321–32. 10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00092-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henderson A. Abused women and peer-provided social support: the nature and dynamics of reciprocity in a crisis setting. Issues Ment Health Nurs 1995;16:117–28. 10.3109/01612849509006929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gómez-Pardo E, Fernández-Alvira JM, Vilanova M, et al. A comprehensive lifestyle peer group–based Intervention on cardiovascular risk factors. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:476–85. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morris R, Morris P. Participants' experiences of hospital-based peer support groups for stroke patients and carers. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:347–54. 10.3109/09638288.2011.607215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark AM, Munday C, McLaughlin D, et al. Peer support to promote physical activity after completion of centre-based cardiac rehabilitation: evaluation of access and effects. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2012;11:388–95. 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2010.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parry M, Watt-Watson J, Hodnett E, et al. Cardiac home education and support trial (chest): a pilot study. Can J Cardiol 2009;25:e393–8. 10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70531-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Power S, Hegarty J. Facilitated peer support in breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 2010;33:E9–16. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181ba9296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arlotti JP, Cottrell BH, Lee SH, et al. Breastfeeding among low-income women with and without peer support. J Community Health Nurs 1998;15:163–78. 10.1207/s15327655jchn1503_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mejias NJ, Gill CJ, Shpigelman C-N. Influence of a support group for young women with disabilities on sense of belonging. J Couns Psychol 2014;61:208–20. 10.1037/a0035462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Angus JE, King-Shier KM, Spaling MA, et al. A secondary meta-synthesis of qualitative studies of gender and access to cardiac rehabilitation. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1758–73. 10.1111/jan.12620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2187–98. 10.1056/NEJMoa1103510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wieslander I, Baigi A, Turesson C, et al. Women’s social support and social network after their first myocardial infarction; A 4-year follow-up with focus on cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005;4:278–85. 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hellem E, Bruusgaard K. “When what is taken for granted disappears”: women’s experiences and perceptions after a cardiac event. Physiother Theory Pract 2018:1–11. 10.1080/09593985.2018.1550829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sjöström-Strand A, Fridlund B. Women's descriptions of symptoms and delay reasons in seeking medical care at the time of a first myocardial infarction: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:1003–10. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, et al. What is an evidence MAP? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev 2016;5. 10.1186/s13643-016-0204-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zainuddin Z, Perera CJ, Haruna H, et al. Literacy in the new norm: stay-home game plan for parents. Inf Learn Sci 2020;121:645–53. 10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oliver S, Harden A, Rees R, et al. An emerging framework for including different types of evidence in systematic reviews for public policy. Evaluation 2005;11:428–46. 10.1177/1356389005059383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.CIHR . Strategy for patient-oriented research capacity development framework: Canadian Institutes of health research, 2015. Available: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/49307.html

- 59.CIHR . Strategy for patient-oriented research patient engagement framework: Canadian Institutes of health research, 2015. Available: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html

- 60.Fawcett J, Watson J, Neuman B, et al. On nursing theories and evidence. J Nurs Scholarsh 2001;33:115–9. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ryan P, Sawin KJ. The individual and family self-management theory: background and perspectives on context, process, and outcomes. Nurs Outlook 2009;57:217–25. 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parry M, Bjørnnes AK, Victor JC, et al. Self-management interventions for women with cardiac pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol 2018;34:458–67. 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gallant MP. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: a review and directions for research. Health Educ Behav 2003;30:170–95. 10.1177/1090198102251030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lorig KR, Mazonson PD, Holman HR. Evidence suggesting that health education for self-management in patients with chronic arthritis has sustained health benefits while reducing health care costs. Arthritis Rheum 1993;36:439–46. 10.1002/art.1780360403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zubatsky M, Berg-Weger M, Morley J. Using telehealth groups to combat loneliness in older adults through COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:1678–9. 10.1111/jgs.16553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grady PA, Gough LL. Self-management: a comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e25–31. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ 2017;358:1–7. 10.1136/bmj.j3453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.SPOR . Recommendations on patient engagement compensation; 2018.

- 70.Foster ED, Deardorff A. Open science framework (OSF). J Med Libr Assoc 2017;105:203–6. 10.5195/jmla.2017.88 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.EPPI . EPPI centre: evidence for policy and practice information and coordinating centre London: social science research unit at the UCL Institute of education;. Available: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/

- 72.Pope C, Mays N, Popay J. Synthesizing qualitative and quantitative health evidence. New York: McGraw Open University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harden A, Garcia J, Oliver S, et al. Applying systematic review methods to studies of people's views: an example from public health research. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:794–800. 10.1136/jech.2003.014829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomas J, Harden A, Oakley A, et al. Integrating qualitative research with trials in systematic reviews. BMJ 2004;328:1010–2. 10.1136/bmj.328.7446.1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Parry M, Bjørnnes AK, Clarke H, et al. Self-management of cardiac pain in women: an evidence MAP. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018549. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, et al. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2007;7:16. 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang DD, Shams-White M, Bright OJM, et al. Creating a literature database of low-calorie sweeteners and health studies: evidence mapping. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:1–11. 10.1186/s12874-015-0105-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Langhorne P, Ramachandra S, Stroke Unit Trialists' Collaboration . Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke: network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;4:CD000197. 10.1002/14651858.CD000197.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Safi S, Sethi NJ, Nielsen EE, et al. Beta-blockers for suspected or diagnosed acute myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;12:CD012484. 10.1002/14651858.CD012484.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;75:40–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Covidence . Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Masterson Creber R, Spadaccio C, Dimagli A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in cardiovascular trials. Can J Cardiol 2021;37:1340–52. 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wagner TH, Yoon J, Jacobs JC, et al. Estimating costs of an implementation intervention. Med Decis Making 2020;40:959–67. 10.1177/0272989X20960455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Polanin JR, Pigott TD, Espelage DL, et al. Best practice guidelines for Abstract screening large‐evidence systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Res Synth Methods 2019;10:330–42. 10.1002/jrsm.1354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Petticrew M, Anderson L, Elder R, et al. Complex interventions and their implications for systematic reviews: a pragmatic approach. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:1211–6. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: a meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:417–30. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.R-Core-Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-067812supp001.pdf (167KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-067812supp002.pdf (68KB, pdf)