Abstract

Background/objective

This study aims to describe the course and to identify poor prognostic factors of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with rheumatic diseases.

Methods

Patients ≥ 18 years of age, with a rheumatic disease, who had confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection were consecutively included by major rheumatology centers from Argentina, in the national, observational SAR-COVID registry between August 13, 2020 and July 31, 2021. Hospitalization, oxygen requirement, and death were considered poor COVID-19 outcomes.

Results

A total of 1915 patients were included. The most frequent rheumatic diseases were rheumatoid arthritis (42%) and systemic lupus erythematosus (16%). Comorbidities were reported in half of them (48%). Symptoms were reported by 95% of the patients, 28% were hospitalized, 8% were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and 4% died due to COVID-19. During hospitalization, 9% required non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) or high flow oxygen devices and 17% invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). In multivariate analysis models, using poor COVID-19 outcomes as dependent variables, older age, male gender, higher disease activity, treatment with glucocorticoids or rituximab, and the presence of at least one comorbidity and a greater number of them were associated with worse prognosis. In addition, patients with public health insurance and Mestizos were more likely to require hospitalization.

Conclusions

In addition to the known poor prognostic factors, in this cohort of patients with rheumatic diseases, high disease activity, and treatment with glucocorticoids and rituximab were associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes. Furthermore, patients with public health insurance and Mestizos were 44% and 39% more likely to be hospitalized, respectively.

Study registration

This study has been registered in ClinicalTrials.gov under the number NCT04568421.

| Key Points |

| • High disease activity, and treatment with glucocorticoids and rituximab were associated with poor COVID-19 outcome in patients with rheumatic diseases. |

| • Some socioeconomic factors related to social inequality, including non-Caucasian ethnicity and public health insurance, were associated with hospitalization due to COVID-19. |

Keywords: Argentina, COVID-19, Rheumatic diseases, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

Since the outbreak of COVID-19 worldwide, rheumatologists have focused their efforts on trying to understand its impact on patients with rheumatic diseases and how to improve management and treatment in case they got infected. Among rheumatic diseases, systemic autoimmune diseases are usually associated with a greater predisposition to viral infections due to the intrinsic risk of the pre-existing disease and to the iatrogenic effect of immunosuppressive drugs used for their treatments [1–3]. They also have a higher prevalence of comorbidities, like cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, which have been associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes [4]. On the other hand, glucocorticoids and some disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have been used to treat inflammation caused by SARS-CoV-2 [5].

Most of the renowned severity risk factors, like male gender, older age, and the presence of comorbidities, are non-modifiable [6]. However, high disease activity and some treatments, including glucocorticoids, rituximab, azathioprine, and cyclophosphamide, which have been associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes in patients with rheumatic diseases are potentially adjustable [7, 8]. The latter must be taken into consideration by rheumatologists when making therapeutic decisions and highlights the importance of a strict control of these patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Most of the information regarding the effect of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic diseases comes from cohorts from other parts of the world and they do not necessarily apply to the Argentine population, considering its sociodemographic and economic characteristics. In this context, and emphasizing the importance of having local data to improve patient management, the Argentine Society of Rheumatology (SAR) developed a national registry of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic diseases (SAR-COVID).

The aim of this study was to evaluate sociodemographic, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with rheumatic diseases from the SAR-COVID registry. Furthermore, we wanted to identify poor prognostic factors of COVID-19.

Methods

The SAR-COVID registry has been previously described [9]. Briefly, it is a national, multicenter, observational registry including consecutive adult patients with a rheumatic disease and confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. COVID-19 diagnosis was made with a positive RT-PCR test from nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab, or positive serology in patients previously diagnosed according to symptoms and close contact with a confirmed patient. A total of 140 independent rheumatologists from all over Argentina registered to participate. All variables were collected by self-report, clinical and laboratory examination, and/or medical records review, performed by the rheumatologist during patient hospitalization due to COVID-19, or at the patient control visit (virtual or face-to-face) performed after SARS-CoV-2 infection, depending on availability.

At baseline, sociodemographic data including age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic level according to the Graffar scale [10], formal education and health insurance, as well as comorbidities, rheumatic treatment, symptoms, and outcomes regarding SARS-CoV-2 infection were recorded. Rheumatic disease activity was stratified into categories based on the treating physician’s criteria (remission, low, moderate, or high disease activity). This analysis comprises the first visit of patients enrolled between August 13, 2020 and July 31, 2021.

Regarding SARS-CoV-2 infection, date, place, and diagnostic method used were registered. Furthermore, symptoms, laboratory findings, pharmacological treatments, and medical interventions, like oxygen therapy, were recorded for all patients. For this study, the following were considered poor COVID-19 outcomes: hospitalization in general ward or admission to the ICU; severe oxygen requirements according to the ordinal scale for clinical improvement from WHO [11], high-flow oxygen devices or non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) or invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV); and death due to COVID-19.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by an independent ethics committee and was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH), the ethical principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki, the law 3301/09, and the guidelines of the local ethics committee. Personal identification data was kept anonymous and protected according to international and national regulations in order to guarantee confidentiality, in accordance with the Law on Protection of Personal Data No. 25.326/2000.

Statistical analysis

Overall comparisons were performed using descriptive statistical analysis of sociodemographic, clinical characteristics, laboratory, and COVID-19 outcomes data. The distribution of continuous variables was evaluated using boxplot, histogram visual inspection, and Shapiro–Wilk test, and they are presented as mean and standard deviation for normal distributions, or median and interquartile range otherwise. Categorical variables are summarized as frequencies and percentages.

To compare associations between sociodemographic and clinical variables and COVID-19 outcomes, chi-square test was used, and if assumptions were not fulfilled, categories were grouped applying Fisher exact test. For continuous variables, Student's t test, Mann–Whitney U test, or ANOVA were used as appropriate. Finally, all variables with a p value less than 0.10 in the univariate analysis and those that, according to the investigator's criteria, were considered relevant were included in multiple regression models (logit link function), using each poor COVID-19 outcome as a dependent variable. Later, variable selection was made using a stepwise method.

A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses and model development were performed using R version 4.0.0 (Free Software Foundation, Inc., Boston, USA).

Results

A total of 1915 patients with rheumatic diseases and SARS-CoV-2 infection were included; most of them were female (80.9%), with a mean age of 51.4 years (SD 14.2). The predominant ethnic groups were Caucasian and Mestizo, 48.6% and 44.1%, respectively. Most of the patients (78.1%) had some type of health insurance different from public health, and regarding socioeconomic level, 50% were classified as middle class. Comorbidities were reported in half of them (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection from the SAR-COVID registry

| Variables | All patients (n = 1915) |

|---|---|

| Female gender n (%) | 1549 (80.9) |

| Age (years) mean (SD) | 51.4 (14.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

|

Caucasian n (%) Mestizo n (%) Other n (%) Unknown n (%) |

931 (48.6) 844 (44.1) 55 (2.9) 85 (4.4) |

| Socioeconomic level | |

|

High n (%) Medium–high n (%) Medium n (%) Medium–low n (%) Low n (%) Unknown n (%) |

39 (2) 328 (17.1) 958 (50) 391 (20.4) 136 (7.1) 63 (3.3) |

| Education (years) mean (SD) | 13.2 (3.8) |

| Health worker n (%) | 126 (6.6) |

|

Health insurance Social security n (%) Private health n (%) Private health + social security n (%) Public health n (%) Unknown n (%) |

929 (48.5) 467 (24.4) 100 (5.2) 396 (20.7) 23 (1.2) |

| Rheumatic disease | |

|

Rheumatoid arthritis n (%) Systemic lupus erythematosus n (%) Spondyloarthritis n (%) Sjögren’s syndrome n (%) Systemic sclerosis n (%) Vasculitis n (%) Antiphospholipid syndrome n (%) Inflammatory myopathy n (%) Osteoarthritis n (%) Fibromyalgia n (%) |

808 (42.2) 308 (16.1) 186 (9.7) 102 (5.3) 81 (4.2) 65 (3.4) 48 (2.5) 51 (2.7) 141 (7.4) 72 (3.8) |

| Disease duration (years) mean (SD) | 8.6 (7.6) |

| Disease activity | |

|

Remission n (%) Low disease activity n (%) Moderate disease activity n (%) High disease activity n (%) Unknown/not applicable n (%) |

634 (33.3) 748 (39.3) 319 (16.7) 63 (3.3) 151 (7.9) |

| Treatment | |

| Glucocorticoid dose | |

|

0 mg/day n (%) ≤ 5 mg/day n (%) > 5 mg/day n (%) Unknown dose n (%) |

1208 (63.8) 591 (31.2) 91 (4.8) 3 (0.2) |

| Conventional DMARDs | |

| Methotrexate n (%) | 714 (37.3) |

| Antimalarials n (%) | 361 (18.9) |

| Leflunomide n (%) | 148 (7.7) |

| Sulfasalazine n (%) | 15 (0.8) |

| Immunosuppressants n (%) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil n (%) | 94 (4.9) |

| Azathioprine n (%) | 79 (4.1) |

| Cyclophosphamide n (%) | 6 (0.3) |

| Cyclosporine n (%) | 1 (0.06) |

| Biologic DMARDs | |

| TNF α inhibitors n (%) | 204 (10.7) |

| Rituximab n (%) | 38 (2) |

| IL-6 inhibitors n (%) | 24 (1.2) |

| Abatacept n (%) | 24 (1.2) |

| IL-17 inhibitors n (%) | 24 (1.2) |

| IL-23 or IL-12/23 inhibitors n (%) | 8 (0.4) |

| Belimumab n (%) | 7 (0.4) |

| Targeted synthetic DMARDs | |

| JAK inhibitors n (%) | 84 (4.4) |

| Apremilast n (%) | 2 (0.1) |

|

Comorbidities n (%) Arterial hypertension n (%) Obesity n (%) Dyslipidemia n (%) Lung disease n (%) Diabetes n (%) Cardiovascular disease n (%) Cancer n (%) Chronic kidney failure n (%) Cerebrovascular disease n (%) |

883 (47.9) 464 (25.3) 262 (14.3) 241 (13.2) 185 (10.1) 144 (7.9) 60 (3.3) 42 (2.3) 34 (1.9) 17 (0.9) |

|

Smoking status Current smoker n (%) Past smoker n (%) Never n (%) Unknown n (%) |

106 (5.6) 382 (20.3) 1211 (64.4) 216 (11.3) |

|

SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic method RT-PCR n (%) Serology n (%) |

1680 (87.7) 259 (13.5) |

|

SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic place Outpatient facility n (%) Emergency department n (%) Home/community detection n (%) Inpatient/hospital n (%) Nursing home or assisted living facility n (%) Unknown n (%) |

871 (45.5) 627 (32.7) 260 (13.6) 160 (8.4 6 (0.3) 7 (0.4) |

|

SARS-CoV-2 contagion Contact with confirmed/possible case n (%) Community contagion n (%) Other n (%) |

1084 (56.6) 726 (37.9) 66 (3.4) |

| Symptoms n (%) | 1819 (95) |

| Fever n (%) | 1069 (55.8) |

| Headache n (%) | 799 (41.7) |

| Cough n (%) | 813 (42.5) |

| Myalgia n (%) | 739 (38.6) |

| General discomfort n (%) | 715 (37.3) |

| Anosmia n (%) | 650 (33.9) |

| Odynophagia n (%) | 559 (29.2) |

| Dyspnea n (%) | 437 (22.8) |

| Arthralgia n (%) | 406 (21.2) |

| Dysgeusia n (%) | 456 (23.8) |

| Pharmacological treatment* n (%) | 570 (29.8) |

| Dexamethasone n (%) | 353 (18.4) |

| Azithromycin n (%) | 297 (15.5) |

| Anticoagulation n (%) | 133 (7) |

| Oral glucocorticoids n (%) | 130 (6.8) |

| Plasma from recovered patients n (%) | 54 (2.8) |

| Antimalarials n (%) | 22 (1.2) |

| Ivermectin n (%) | 36 (1.9) |

|

Complications n (%) ARDS n (%) Sepsis n (%) Cytokine storm n (%) |

171 (9) 11 (6) 37 (1.9) 11 (0.6) |

| Hospitalization n (%) | 512 (26.8) |

| Hospitalization time (days) median (Q1, Q3) | 10.0 (6.0, 15.0) |

| ICU admission n (%) | 153 (8) |

| ICU time (days) median (Q1, Q3) | 8.0 (5.0, 14.0) |

| O2 treatment n (%) | |

|

Supplemental oxygen n (%) NIMV/high-flow O2 n (%) IMV n (%) Ventilation, unknown n (%) Unknown n (%) |

220 (43.5) 45 (8.9) 84 (16.6) 2 (0.4) 2 (0.4) |

| Death due to COVID-19 n (%) | 83 (4.4) |

n number, SD standard deviation, DMARDs disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, TNF tumor necrosis factor, IL interleukin, RT-PCR reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction, ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome, Q quartile, ICU intensive care unit, O2 oxygen, NIMV non-invasive mechanical ventilation, IMV invasive mechanical ventilation

*Excludes analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

The most frequent immune-mediated diseases were rheumatoid arthritis (42.0%), systemic lupus erythematosus (16.0%), and spondyloarthritis (9.7%). At the time of COVID-19 infection, most were in remission or minimal/low disease activity (78%). In relation to treatment, 36% were receiving glucocorticoids, 37.3% methotrexate, 18.9% antimalarials, 17% biologic DMARDs, and 4% JAK inhibitors (Table 1).

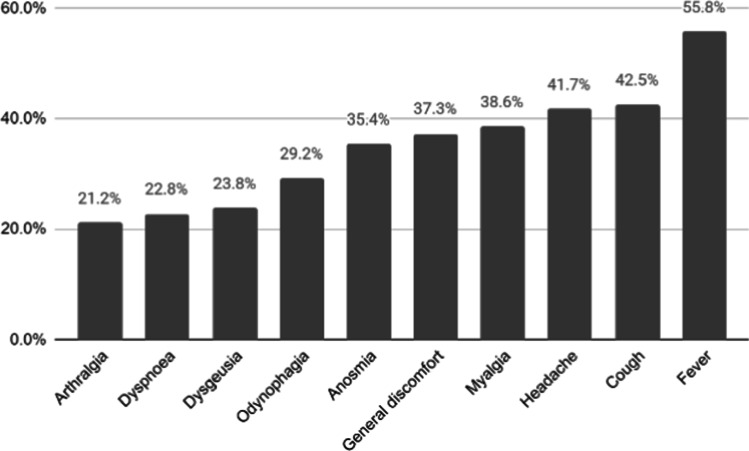

After infection, patients were followed for a median time of 62.0 days (Q1, Q3 30.8, 141.0). COVID-19 symptoms were present in 95% of the patients and were mostly fever, cough, and headache (Fig. 1). During infection, 29.8% received some pharmacological treatment, dexamethasone being the most frequently used. A quarter (26.8%) of the patients were hospitalized and 8% were admitted to the ICU. Among hospitalized patients, 8.9% required high-flow oxygen devices or NIMV and 16.6% IMV. Median hospital stay was 10.0 days (Q1, Q3 6.0, 15.0). Complications were reported in 9%, being acute respiratory distress syndrome the most frequent (6%). A total of 83 (4.4%) patients died due to COVID-19 during follow up.

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 symptoms most frequently reported in the SAR-COVID registry

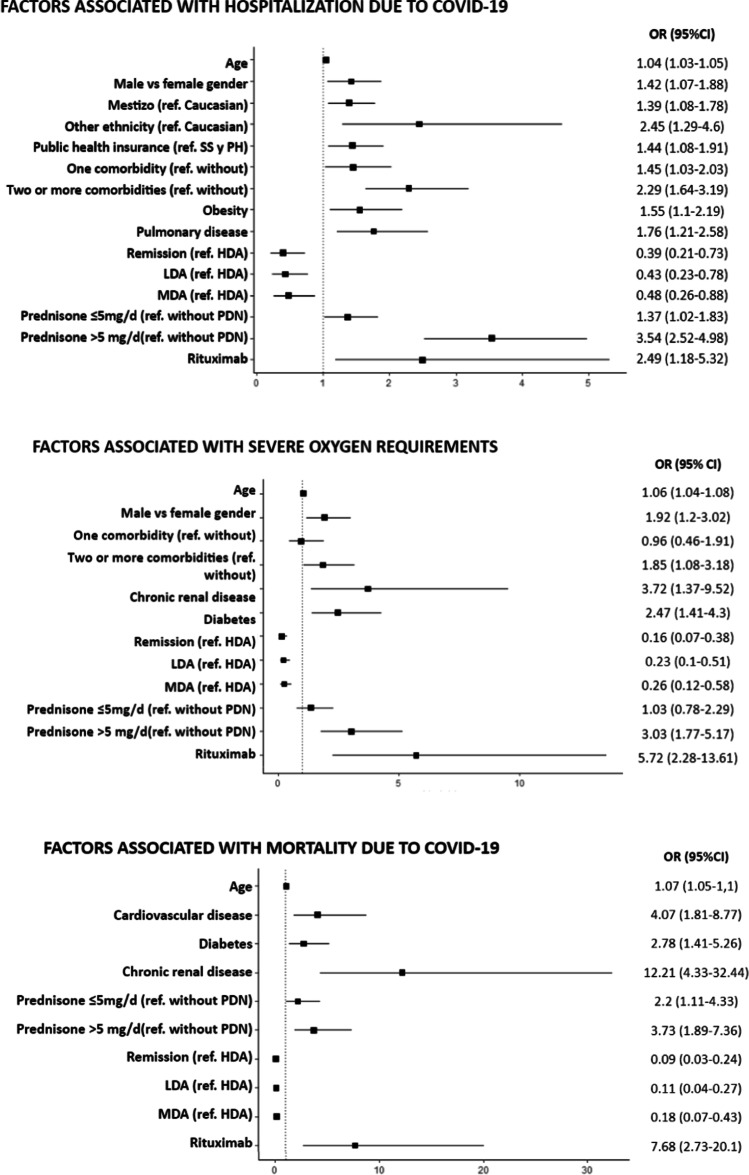

Older patients, male gender, and the presence of comorbidities were associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes. In the univariate analysis, men were more frequently hospitalized and were more likely to require oxygen than females. Patients who were hospitalized, had severe oxygen requirements, or died were significantly older than those without these outcomes. Similarly, the presence and number of comorbidities was associated with all three outcomes. Individually, every comorbidity was more frequent in patients with poor COVID-19 outcomes (Tables 2, 3, and 4). After adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical variables, male gender remained significantly associated with hospitalization, and older age with all three outcomes. The presence of at least one comorbidity was associated with a higher likelihood of being hospitalized compared to patients without comorbidities, and two or more comorbidities was more commonly associated with severe oxygen therapy. Furthermore, obesity and pulmonary disease were associated with hospitalization; diabetes and chronic renal disease with severe oxygen requirements and death; and cardiovascular disease with death (Fig. 2A–C).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables associated with COVID-19 hospitalization

| Variables | Not hospitalized n = 1403 |

Hospitalized n = 512 |

p value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender n (%) | 1155 (82.3) | 394 (77.0) | 0.010 | 1.39 (1.09, 1.78) |

| Age (years) mean (SD) | 49.3 (13.5) | 57.2 (14.4) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (1.03, 1.05) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

|

Caucasian n (%) Mestizo n (%) Others n (%) Unknown n (%) |

722 (51.5) 603 (43) 32 (2.3) 46 (3.3) |

209 (40.8) 241 (47.1) 23 (4.5) 39 (7.6) |

< 0.001 |

Ref: Caucasian 1.38 (1.11, 1.71) 2.48 (1.41, 4.32) – |

| Socioeconomic level | ||||

|

High n (%) Medium–high n (%) Medium n (%) Medium–low n (%) Low n (%) Unknown n (%) |

34 (2.5) 85 (6.3) 262 (19.4) 707 (52.2) 266 (19.6) 49 (3.5) |

5 (1) 51 (10.2) 66 (13.3) 251 (50.4) 125 (25.1) 14 (2.7) |

< 0.001 |

Ref: High 1.71 (0.70, 5.15) 2.41 (1.02, 7.10) 3.20 (1.33, 9.49) 4.08 (1.62, 12.5) – |

| Education (years) mean (SD) | 13.5 (3.7) | 12.4 (3.9) | < 0.001 | 0.93 (0.90, 0.96) |

| Health insurance | ||||

|

Social security n (%) Private health n (%) Private health + social security n (%) Public health n (%) Unknown n (%) |

678 (48.3) 367 (26.2) 76 (5.42) 264 (18.8) 18 (1.3) |

251 (49.0) 100 (19.5) 24 (4.7) 132 (25.8) 5 (1.0) |

0.003 |

Ref: Social security 0.74 (0.56, 0.96) 0.85 (0.52, 1.36) 1.35 (1.05, 1.74) – |

| Rheumatic disease | ||||

|

Rheumatoid arthritis n (%) Systemic lupus erythematosus n(%) Spondyloarthritis n (%) Sjögren’s syndrome n (%) Systemic sclerosis n (%) Vasculitis n (%) Antiphospholipid syndrome n (%) Inflammatory myopathy n (%) Osteoarthritis n (%) Fibromyalgia n (%) |

591 (42.1) 228 (16.3) 149 (10.6) 75 (5.4) 51 (3.6) 34 (2.4) 36 (2.6) 30 (2.1) 108 (7.7) 58 (4.1) |

217 (42.4) 80 (15.6) 37 (7.2) 27 (5.3) 27 (5.3) 31 (6.1) 12 (2.3) 21 (4.1) 33 (6.5) 14 (2.7) |

0.961 0.795 0.033 1.000 0.044 < 0.001 0.912 0.028 0.407 0.197 |

1.01 (0.82, 1.20) 0.95 (0.72, 1.25) 0.66 (0.44, 0.94) 0.99 (0.62, 1.53) 1.65 (1.03, 2.60) 2.60 (1.57, 4.27) 0.91 (0.45, 1.72) 1.96 (1.10, 3.43) 0.83 (0.54, 1.22) 0.65 (0.35, 1.15) |

| Disease duration (years) mean (SD) | 8.4 (7.4) | 9.3 (8.3) | 0.111 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) |

| Disease activity | ||||

|

Remission n (%) Low disease activity n (%) Moderate disease activity n (%) High disease activity n (%) Unknown/not applicable n (%) |

506 (38.7) 561 (43) 211 (16.2) 28 (2.1) 97 (6.9) |

128 (27.9) 187 (40.8) 108 (23.6) 35 (7.6) 54 (10.5) |

< 0.001 |

Ref: Remission 1.32 (1.02, 1.70) 2.02 (1.49, 2.74) 4.94 (2.91, 8.48) – |

| Treatment | ||||

| Glucocorticoid dose | ||||

|

0 mg/day n (%) ≤ 5 mg/day n (%) > 5 mg/day n (%) Dose unknown |

961 (69.2) 382 (27.5) 43 (3.10) 3 (0.216) |

247 (49.0) 209 (41.5) 48 (9.52) 0 (0) |

< 0.001 |

Ref: 0 mg/day 2.13 (1.71, 2.65) 4.34 (2.81, 6.73) – |

| Conventional DMARDs | ||||

| Methotrexate n (%) | 545 (38.8) | 169 (33) | 0.022 | 0.78 (0.63, 0.96) |

| Antimalarials n (%) | 278 (19.8) | 83 (16.2) | 0.086 | 0.78 (0.60, 1.02) |

| Leflunomide n (%) | 106 (7.6) | 42 (8.2) | 0.709 | 1.09 (0.75, 1.58) |

| Sulfasalazine n (%) | 10 (0.7) | 5 (1) | 0.563 | 1.37 (0.43, 3.89) |

| Immunosuppressants | ||||

| Mycophenolate mofetil n (%) | 65 (4.6) | 29 (5.7) | 0.421 | 1.24 (0.78, 1.92) |

| Azathioprine n (%) | 47 (3.4) | 32 (6.3) | 0.007 | 1.92 (1.20, 3.04) |

| Cyclophosphamide n (%) | 2 (0.1) | 4 (0.8) | 0.047 | 5.52 (1.07, 39.9) |

| Cyclosporine n (%) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | – |

| Biological DMARDs | ||||

| TNF-α inhibitors n (%) | 170 (12.1) | 34 (6.6) | < 0.001 | 0.52 (0.35, 0.75) |

| Rituximab n (%) | 17 (1.2) | 21 (4.1) | < 0.001 | 3.49 (1.83, 6.75) |

| IL-6 inhibitors n (%) | 17 (1.2) | 7 (1.4) | 0.969 | 1.13 (0.43, 2.64) |

| Abatacept n (%) | 16 (1.1) | 8 (1.6) | 0.615 | 1.38 (0.55, 3.15) |

| IL-17 inhibitors n (%) | 21 (1.5) | 3 (0.6) | 0.176 | 0.39 (0.09, 1.13) |

| IL-23 or IL-12/23 inhibitors n (%) | 6 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 1.000 | 0.91 (0.13, 3.98) |

| Belimumab n (%) | 6 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 0.683 | 0.46 (0.02, 2.68) |

| Targeted synthetic DMARDs | ||||

| JAK inhibitors n (%) | 59 (4.2) | 25 (4.9) | 0.607 | 1.15 (0.70, 1.83) |

| Apremilast n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) | 0.071 | – |

|

Comorbidities n (%) Arterial hypertension n (%) Obesity n (%) Dyslipidemia n (%) Lung disease n (%) Diabetes n (%) Cardiovascular disease n (%) Cancer n (%) Chronic kidney failure n (%) Cerebrovascular disease n (%) |

534 (39.5) 257 (19.1) 133 (9.9) 139 (10.4) 81 (6.1) 69 (5.2) 25 (1.9) 27 (2) 12 (0.9) 6 (0.4) |

349 (70.8) 207 (42.2) 110 (22.9) 102 (21.6) 104 (21.4) 75 (15.4) 75 (15.4) 16 (3.3) 22 (4.5) 11 (2.3) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 0.152 < 0.001 < 0.001 |

3.71 (2.98, 4.65) 3.09 (2.47, 3.87) 2.70 (2.04, 3.56) 2.38 (1.79, 3.15) 4.22 (3.10, 5.79) 3.36 (2.38, 4.75) 4.16 (2.47, 7.10) 1.66 (0.87, 3.08) 5.24 (2.62, 11.0) 5.18 (1.96, 15.10) |

| Smoking status | ||||

|

Current smoker n (%) Past smoker n (%) Never n (%) Unknown n (%) |

83 (6.60) 240 (19.1) 935 (74.3) 145 (10.3) |

23 (5.2) 142 (32.2) 276 (62.6) 71 (13.9) |

< 0.001 |

Ref: Current smoker 2.14 (1.31, 3.61) 1.07 (0.67, 1.76) – |

n number, SD standard deviation, ref reference, DMARDs disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, TNF tumor necrosis factor, IL interleukin

Table 3.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables associated with severe oxygen requirements due to COVID-19

| Variables | No severe O2 requirement n = 1784 |

Severe O2 requirement n = 131 |

p value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender n (%) | 1458 (81.7) | 91 (69.5) | < 0.001 | 1.97 (1.32, 2.89) |

| Age (years) mean (DE) | 50.6 (14.0) | 61.6 (13.6) | < 0.001 | 1.06 (1.05, 1.08) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

|

Caucasian n (%) Mestizo n (%) Others n (%) Unknown n (%) |

872 (48.9) 791 (44.3) 47 (2.6) 74 (4.1) |

59 (45) 53 (40.5) 8 (6.1) 11 (8.4) |

0.012 |

Ref: Caucasian 2.20 (1.05, 4.21) 0.99 (0.67, 1.45) – |

| Socioeconomic level | ||||

|

High n (%) Medium–high n (%) Medium n (%) Medium–low n (%) Low n (%) Unknown n (%) |

36 (2) 312 (18.1) 897 (51.9) 358 (20.7) 124 (7.2) 57 (3.2) |

3 (2.3) 16 (12.8) 61 (48.8) 33 (26.4) 12 (9.6) 6 (4.6) |

0.308 |

Ref: High 0.62 (0.19, 2.74) 0.82 (0.28, 3.45) 1.11 (0.37, 4.76) 1.16 (0.35, 5.30) – |

| Education (years) mean (SD) | 13.3 (3.75) | 12.5 (4.17) | 0.066 | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) |

| Health insurance | ||||

|

Social security n (%) Private health n (%) Private health + social security n (%) Public health n (%) Unknown n (%) |

856 (48.) 441 (24.7) 95 (5.3) 369 (20.7) 23 (1.3) |

73 (55.7) 26 (19.8) 5 (3.8) 27 (20.6) 0 (0) |

0.382 |

Ref: Social security 1.17 (0.75, 1.87) 0.81 (0.46, 1.41) 0.72 (0.24, 1.77) – |

| Rheumatic disease | ||||

|

Rheumatoid arthritis n (%) Systemic lupus erythematosus n (%) Spondyloarthritis n (%) Sjögren’s syndrome n (%) Systemic sclerosis n (%) Vasculitis n (%) Antiphospholipid syndrome n (%) Inflammatory myopathy n (%) Osteoarthritis n (%) Fibromyalgia n (%) |

751 (42.1) 293 (16.4) 176 (9.9) 100 (5.6) 76 (4.3) 47 (2.6) 45 (2.5) 47 (2.6) 131 (7.3) 70 (3.9) |

57 (43.5) 15 (11.5) 10 (7.6) 2 (1.5) 5 (3.8) 18 (13.7) 18 (2.3) 4 (3.0) 10 (7.6) 2 (1.5) |

0.822 0.170 0.497 0.071 0.985 < 0.001 1.000 0.775 1.000 0.231 |

1.06 (0.74, 1.51) 0.66 (0.36, 1.11) 0.76 (0.37, 1.40) 0.26 (0.04, 0.84) 0.89 (0.31, 2.04) 5.89 (3.24, 10.30) 0.91 (0.22, 2.52) 1.16 (0.35, 2.92) 1.04 (0.50, 1.94) 0.38 (0.06, 1.23) |

| Disease duration (years) mean (SD) | 8.5 (7.5) | 10.7 (9.1) | 0.007 | 1.03 (1.01, 1.06) |

| Disease activity | ||||

|

Remission n (%) Low disease activity n (%) Moderate disease activity n (%) High disease activity n (%) Unknown/not applicable n (%) |

700 (42.5) 293 (17.8) 609 (36.9) 47 (2.9) 135 (7.6) |

48 (41.7) 26 (22.6) 25 (21.7) 16 (12.2) 16 (12.2) |

< 0.001 |

Ref: Remission 8.29 (4.08, 16.5) 1.67 (1.03, 2.78) 2.16 (1.22, 3.82) – |

| Treatment | ||||

| Glucocorticoid dose | ||||

|

0 mg/day n (%) ≤ 5 mg/day n (%) > 5 mg/day n (%) Unknown dose n (%) |

1155 (65.5) 535 (30.3) 71 (4.0) 3 (0.2) |

53 (41.1) 56 (43.4) 20 (15.5) 0 (0) |

< 0.001 |

Ref: 0 mg/day 2.28 (1.54, 3.37) 6.14 (3.42, 10.70) – |

| Conventional DMARDs | ||||

| Methotrexate n (%) | 676 (37.9) | 38 (29.0) | 0.053 | 0.67 (0.45, 0.98) |

| Antimalarials n (%) | 347 (19.5) | 14 (10.7) | 0.018 | 0.50 (0.27, 0.84) |

| Leflunomide n (%) | 144 (8.1) | 4 (3.1) | 0.057 | 0.36 (0.11, 0.87) |

| Sulfasalazine n (%) | 13 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) | 0.274 | 2.11 (0.33, 7.75) |

| Immunosuppressants | ||||

| Mycophenolate mofetil n (%) | 87 (4.9) | 7 (5.3) | 0.977 | 1.10 (0.45, 2.27) |

| Azathioprine n (%) | 67 (3.8) | 12 (9.2) | 0.006 | 2.58 (1.30, 4.74) |

| Cyclophosphamide n (%) | 4 (0.2) | 2 (1.5) | 0.058 | 6.90 (0.95, 35.70) |

| Cyclosporine n (%) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 | – |

| Biological DMARDs | ||||

| TNF-α inhibitors n (%) | 195 (10.9) | 9 (6.9) | 0.191 | 0.60 (0.28, 1.14) |

| Rituximab n (%) | 26 (1.5) | 12 (9.2) | < 0.001 | 6.82 (3.25, 13.60) |

| IL-6 inhibitors n (%) | 22 (1.2) | 2 (1.5) | 0.678 | 1.24 (0.20, 4.28) |

| Abatacept n (%) | 22 (1.2) | 2 (1.5) | 0.678 | 1.24 (0.20, 4.28) |

| IL-17 inhibitors n (%) | 24 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0.404 | – |

| IL-23 or IL-12/23 inhibitors n (%) | 7 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0.433 | 1.95 (0.10, 11.1) |

| Belimumab n (%) | 6 (0.3) | 1 (0.8) | 0.392 | 2.28 (0.12, 13.5) |

| Targeted synthetic DMARDs | ||||

| JAK inhibitors n (%) | 78 (4.4) | 6 (4.6) | 1 | 1.04 (0.40, 2.24) |

| Apremilast n (%) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 | – |

|

Comorbidities n (%) Arterial hypertension n (%) Obesity n (%) Dyslipidemia n (%) Lung disease n (%) Diabetes n (%) Cardiovascular disease n (%) Cancer n (%) Chronic kidney failure n (%) Cerebrovascular disease n (%) |

784 (45.7) 401 (23.5) 228 (13.4) 209 (12.4) 155 (9.1) 113 (6.7) 44 (2.6) 36 (2.1) 22 (1.3) 14 (0.8) |

99 (77.3) 63 (49.6) 34 (26.8) 32 (26.4) 30 (23.8) 31 (24.4) 16 (13.1) 7 (5.6) 12 (9.5) 3 (2.4) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 0.0025 < 0.001 0.106 |

4.06 (2.69, 6.31) 3.20 (2.22, 4.62) 2.46 (1.58, 3.73) 2.55 (1.64, 3.88) 3.11 (1.97, 4.79) 4.53 (2.86, 7.02) 5.64 (3.00, 10.10) 2.72 (1.09, 5.88) 7.95 (3.73, 16.20) 2.95 (0.67, 9.18) |

| Smoking status | ||||

|

Current smoker n (%) Past smoker n (%) Never n (%) Unknown n (%) |

97 (6.1) 346 (21.8) 1144 (72.1) 197 (11) |

9 (8) 36 (32.1) 67 (59.8) 19 (14.5) |

0.02 |

Ref: Current smoker 1.12 (0.54, 2.55) 0.63 (0.32, 1.39) – |

n number, SD standard deviation, Ref reference, DMARDs disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, TNF tumor necrosis factor, IL interleukin

Table 4.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables associated with death due to COVID-19

| Variables | Alive n = 1832 |

Death n = 83 |

p value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender n (%) | 1489 (81.3) | 60 (72.3) | 0.058 | 1.66 (1.00, 2.69) |

| Age (years) mean (DE) | 50.9 (14) | 63 (13.1) | < 0.001 | 1.07 (1.05, 1.09) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

|

Caucasian n (%) Mestizo n (%) Others n (%) Unknown n (%) |

891 (50.8%) 813 (46.3%) 51 (2.91%) 77 (4.2%) |

40 (53.3) 31 (41.3) 4 (5.3) 8 (9.6) |

0.388 |

Ref: Caucasian 2.31 (0.98, 4.88 0.85 (0.52, 1.37 1.75 (0.51, 4.55 |

| Socioeconomic level | ||||

|

High n (%) Medium–high n (%) Medium n (%) Medium–low n (%) Low n (%) Unknown n (%) |

39 (2.2) 316 (17.8) 920 (51.9) 369 (20.8) 129 (7.3) 59 (3.2) |

0 (0) 12 (15.2) 38 (48.1) 22 (27.8) 7 (8.1) 4 (4.8) |

0.418 |

0.00 (0.00, 6,16) 0.70 (0.28, 1.92) 0.76 (0.35, 1.89) 1.10 (0.48, 2.83) Ref: Low – |

| Education (years) mean (SD) | 13.3 (3.8) | 11.6 (3.8) | < 0.001 | 0.89 (0.83, 0.95) |

| Health insurance | ||||

|

Social security n (%) Private health n (%) Private health + social security n (%) Public health n (%) Unknown n (%) |

877 (47.9) 456 (24.9) 98 (5.4) 378 (20.6) 23 (1.3) |

52 (62.7) 11 (13.3) 2 (2.4) 18 (21.7) 0 (0) |

0.04 |

Ref: Social security 0.41 (0.20, 0.76) 0.34 (0.06, 1.13) 0.80 (0.45, 1.37) – |

| Rheumatic disease | ||||

|

Rheumatoid arthritis n (%) Systemic lupus erythematosus n (%) Spondyloarthritis n (%) Sjögren’s syndrome n (%) Systemic sclerosis n (%) Vasculitis n (%) Antiphospholipid syndrome n (%) Inflammatory myopathy n (%) Osteoarthritis n (%) Fibromyalgia n (%) |

774 (42.2) 298 (16.3) 185 (10.1) 101 (5.5) 75 (4.1) 51 (2.8) 45 (2.5) 46 (2.5) 138 (7.5) 70 (3.8) |

34 (41) 10 (12) 1 (1.2) 1 (1.2) 6 (7.2) 14 (16.9) 3 (3.6) 5 (6) 3 (3.6) 2 (2.4) |

0.906 0.384 0.0.13 0.127 0.160 < 0.001 0.462 0.067 0.262 0.767 |

0.95 (0.60, 1.48) 0.71 (0.34, 1.32) 0.11 (0.01, 0.49) 0.21 (0.01, 0.96) 1.83 (0.69, 4.00) 7.09 (3.62, 13.10) 1.49 (0.36, 4.19) 2.49 (0.85, 5.89) 0.46 (0.11, 1.25) 0.62 (0.10, 2.03) |

| Disease duration (years) mean (SD) | 8.6 (7.6) | 10.2 (8.9) | 0.080 | 1.03 (1.00, 1.05) |

| Disease activity | ||||

|

Remission n (%) Low disease activity n (%) Moderate disease activity n (%) High disease activity n (%) Unknown/not applicable n (%) |

618 (36.6) 722 (42.7) 300 (17.8) 49 (2.9) 143 (7.8) |

16 (21.3) 26 (34.7) 19 (25.3) 14 (18.7) 8 (9.6) |

< 0.001 |

Ref: Remission 11.0 (5.04, 24.00) 1.39 (0.75, 2.67) 2.45 (1.24, 4.88) – |

| Treatment | ||||

| Glucocorticoid dose | ||||

|

0 mg/day n (%) …… ≤ 5 mg/day n (%) > 5 mg/day n (%) > Unknown dose n (%) |

1182 (65.2) 549 (30.3) 78 (4.3) 3 (0.2) |

26 (32.1) 42 (51.9) 13 (16) 0 (0) |

< 0.001 |

Ref: 0 mg/day 3.48 (2.12, 5.80) 7.58 (3.65, 15.10) – |

| Conventional DMARDs | ||||

| Methotrexate n (%) | 690 (37.7) | 24 (28.9) | 0.135 | 0.67 (0.41, 1.08) |

| Antimalarials n (%) | 350 (19.1) | 11 (13.3) | 0.234 | 0.65 (0.32, 1.18) |

| Leflunomide n (%) | 146 (8) | 2 (2.4) | 0.100 | 0.29 (0.05, 0.92) |

| Sulfasalazine n (%) | 15 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | – |

| Immunosuppressants | ||||

| Mycophenolate mofetil n (%) | 88 (4.8) | 6 (7.2) | 0.296 | 1.54 (0.59, 3.37) |

| Azathioprine n (%) | 74 (4) | 5 (6) | 0.388 | 1.52 (0.52, 3.52) |

| Cyclophosphamide n (%) | 6 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | – |

| Cyclosporine n (%) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | – |

| Biological DMARDs | ||||

| TNF-α inhibitors n (%) | 199 (10.9) | 5 (6) | 0.224 | 0.53 (0.18, 1.19) |

| Rituximab n (%) | 29 (1.6) | 9 (10.8) | < 0.001 | 7.56 (3.27, 16.00) |

| IL-6 inhibitors n (%) | 24 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0.622 | – |

| Abatacept n (%) | 22 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 0.279 | 2.03 (0.32, 7.06) |

| IL-17 inhibitors n (%) | 24 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0.622 | – |

| IL-23 or IL-12/23 inhibitors n (%) | 8 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | – |

| Belimumab n (%) | 6 (0.3) | 1 (1.2) | 0.267 | 3.71 (0.20, 22.10) |

| Targeted synthetic DMARDs | ||||

| JAK inhibitors n (%) | 81 (4.4) | 3 (3.6) | 1.000 | 0.80 (0.19, 2.20) |

| Apremilast n (%) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | – |

|

Comorbidities n (%) Arterial hypertension n (%) Obesity n (%) Dyslipidemia n (%) Lung disease n (%) Diabetes n (%) Cardiovascular disease n (%) Cancer n (%) Chronic kidney failure n (%) Cerebrovascular disease n (%) |

819 (46.4) 424 (24.2) 243 (13.9) 224 (12.9) 162 (9.3) 124 (7.1) 46 (2.7) 38 (2.) 23 (1.3) 15 (0.9) |

64 (80) 40 (50.6) 19 (24.1) 17 (23) 23 (29.5) 20 (25.3) 14 (18.4) 5 (6.4) 11 (13.9) 2 (2.6) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 0.018 0.020 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 0.034 < 0.001 0.160 |

4.62 (2.72, 8.33) 3.22 (2.04, 5.08) 2.23 (1.27, 3.74) 2.01 (1.12, 3.45) 4.09 (2.41, 6.75) 4.43 (2.53, 7.48) 8.29 (4.20, 15.50) 3.08 (1.04, 7.39) 12.1 (5.49, 25.40) 3.07 (0.48, 11.10) |

| Smoking status | ||||

|

Current smoker n (%) Past smoker n (%) Never n (%) Unknown n (%) |

104 (6.4) 357 (21.9) 1170 (71.7) 201 (11) |

2 (2.9) 25 (36.8) 41 (60.3) 15 (18.1) |

0.012 |

Ref: Current smoker 3.64 (1.06, 22.9) 1.82 (0.55, 11.3) – |

n number, SD standard deviation, Ref reference, DMARDs disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, TNF tumor necrosis factor, IL interleukin

Fig. 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with A hospitalization, B severe oxygen requirements, and C death due to COVID-19. Only significant associations are shown. The models have been adjusted for the following variables: sex, age, ethnicity, socioeconomic level, health insurance, education, comorbidities, smoking status, rheumatic disease diagnostic, activity, and treatment. ref, reference; SS, social security; PH, private health; HDA, high disease activity; MDA, moderate disease activity; LDA, low disease activity; PDN, prednisone

Regarding socioeconomic status, hospitalized patients were more frequently non-Caucasians, had public health insurance, and had lower socioeconomic status. Likewise, patients who died had more frequently social security and less frequently private health insurance. Moreover, fewer years of schooling was associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes (Tables 2–4). In multivariable analysis, after adjusting for other demographic and clinical risk factors, being non-Caucasian and having public health insurance were still associated with hospitalization (Fig. 2A–C).

Patients with vasculitis were more frequently hospitalized, required severe oxygen therapy, and were more likely to die from COVID-19. Those with systemic sclerosis and inflammatory myopathy were more frequently hospitalized, whereas spondyloarthritis was associated with less hospitalizations and deaths. Nonetheless, high disease activity was associated with all three poor outcomes. Regarding rheumatic disease treatment, glucocorticoids and rituximab were more frequently used among patients who were hospitalized, required severe oxygen treatment, and died. In addition, cyclophosphamide and azathioprine were more commonly used in hospitalized patients, and the latter also in those with severe oxygen treatment. On the contrary, treatment with methotrexate or TNF inhibitors was associated with outpatient care and antimalarials with no severe oxygen requirement (Tables 2–4).

In multivariate analysis, treatment with rituximab was associated with a 2.5-fold increase of hospitalization, sixfold increase of severe oxygen requirement, and eightfold increase of death due to COVID-19. Even 5 mg/day or less of prednisone was associated with hospitalization and death. On the contrary, patients in remission and with low or moderate disease activity had better COVID-19 outcomes compared to those with high disease activity (Fig. 2A–C).

Finally, to assess factors associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes in a more balanced population, we decided to perform a sensitivity analysis including only data from three major clinics, where physicians thoroughly assessed all patients with rheumatic disease and SARS-CoV-2 infection. From a total of 320 patients studied, 21 (6.6%) were hospitalized. Similar to the general cohort, hospitalized patients were older (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00–1.06), had more comorbidities (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2–2.1), more frequently vasculitis (OR 6.6, 95% CI 2.2–18.7), moderate and high disease activity (ref. remission OR 5.3, 95% CI 1.5–21.5 and OR 26.5, 95% CI 6.6–120.0, respectively), and treatment with glucocorticoids (≤ 5 mg/day: OR 8.6, 95% CI 2.2–42.1 and > 5 mg/day: OR 12.9, 95% CI 3.9–58.1) and rituximab (OR 10.4, 95% CI 1.3–66.4).

Discussion

This is the first report of poor COVID-19 outcomes, including hospitalization, severe oxygen requirements, and death, in Argentine patients with rheumatic diseases from the SAR-COVID registry. Demographic and clinical variables were analyzed as well as socioeconomic characteristics. Particularly, male sex, older age, the presence of comorbidities, high disease activity, and treatment with glucocorticoids and rituximab were associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes. In addition, Mestizos and those with public health insurance were more likely to be hospitalized.

Male gender, older age, and comorbidities were associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes. Men were twice more likely to be hospitalized or to require at least high-flow oxygen therapy. Moreover, every extra year beyond 18 years of age represented a 4%, 6%, and 7% increased risk of hospitalization, severe oxygen requirement, and death, respectively. Similar results were observed by Schönfeld et al. [6] studying the general Argentine population; male gender was associated with ICU admission and death with an OR of 1.49 (95% CI 1.43–1.56) and individuals over 60 years old were almost five times more likely to reach this composite outcome. Likewise, arterial hypertension, diabetes, obesity, pulmonary disease, heart failure, malignancy, and chronic renal disease were identified as poor prognostic factors [6]. These factors have also been associated with hospitalization and death during SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with rheumatic diseases [7, 8].

Univariate analysis showed that variables related to social inequality, like lower socioeconomic status, less education, and public health insurance, were more frequent among patients with worse COVID-19 outcomes. Also, Mestizos and other non-Caucasian ethnicities were more frequently hospitalized and required more severe oxygen therapy. It could be argued that patients with lower socioeconomic status have higher disease activity as a result of having less access to medical care and treatments; however, even after adjusting for clinical variables, patients with public health insurance and Mestizos were 44% and 39% more likely to be hospitalized, respectively. Likewise, data from one of the most affected areas with COVID-19 of Argentina, Buenos Aires City, showed that neighborhoods with higher mortality rates had more households with unsatisfied needs (UBN) compared to districts with lower mortality. In addition, two items included in the UBN index, particularly overcrowding and homes without bathrooms, could have a direct relationship with the spread of the virus [12]. The association between mortality due to COVID-19 and poor socioeconomic status was also described in other South American countries, like Brazil and Chile [13, 14]. This could be related to less social distancing measures, insufficient testing, poor public health interventions, test result delays, and higher fatality rates in the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum [15]. On the other hand, data provided by the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance (GRA) showed that ethnicity was associated with different COVID-19 outcomes. Particularly, after adjusting for poor prognostic factors, Latins were almost twice more likely to be hospitalized and die due to SARS-CoV-2 infection [16]. In addition, an analysis including over 14,000 patients from 23 countries proved that countries with low socioeconomic status, environmental exposures, scarce medical resources, and few government-imposed containment measures were independently associated with higher odds of death attributed to COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic diseases [17]. These results highlight the importance of public health approaches to reduce the consequences of socioeconomic inequalities in order to improve SARS-CoV-2 detection and prompt access to the healthcare system.

Regarding rheumatic diseases, and in concordance with data from the COVID-19 GRA and other European cohorts [7, 8, 18, 19], high disease activity and treatment with glucocorticoids and rituximab were associated with all three poor outcomes. In this study, patients taking at least 5 mg/day of prednisolone or rituximab were almost four and eight times more likely to die from COVID-19, respectively. Similarly, Strangfeld et al. showed that patients with rheumatic diseases taking rituximab and glucocorticoids over 10 mg/day and those with high disease activity were 4.0, 1.7, and 1.9 times more likely to die due to COVID-19, respectively [7]. In addition, the same group also described the association between immunosuppressants and JAK inhibitors with poor outcomes [7, 19, 20]. Here, although the use of azathioprine and cyclophosphamide was more frequent among patients with severe COVID-19, it did not reach statistical significance in the multivariable analysis, probably because of the small sample size of this group. In relation to JAK inhibitors, we did not find differences in our study.

Although some studies have shown that patients with rheumatic diseases have more severe COVID-19 compared to the general population, existing data is conflicting [21–26]. The design of our study only allowed for indirect comparisons with a population without rheumatic conditions. According to the report of July 31, 2021 from the Ministry of Health (cut-off date of this analysis), 4,929,764 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection had been confirmed, of which 4,569,552 patients had recovered and 105,721 (2.1%) had died (27). Overall mortality in our cohort was 4.4%. This difference can be due to several factors. First, the general population was younger and had a lower frequency of comorbidities, which have been identified as poor prognostic factors. Furthermore, our registry overrepresents COVID-19 patients with only 5% of asymptomatic patients and higher frequency of female sex. In addition, those with rheumatic diseases presented other factors that have been associated with a worse outcome of COVID-19, particularly disease activity and their treatments, whose impact has been observed in our cohort as well as in other registries in Latin America and the world [7, 8, 28–30]. As the latter are potentially modifiable factors, the role of the rheumatologist during the pandemic is of great relevance. Patients with rheumatic diseases should be encouraged to continue their medical check-ups in order to minimize disease activity and ensure early detection of disease flares. Moreover, rheumatologists should choose the best treatment possible considering risks and benefits of every drug and promote the vaccination of patients taking into account international recommendations [31, 32].

Given the observational design, there are some limitations to the registry. First, there could be an inclusion bias since the data is voluntarily reported by rheumatologists. Marketing campaigns by SAR are constantly being carried out to promote patient inclusion, and now almost 15% of SAR members are participating in this project. Most of them belong to the Buenos Aires metropolitan area, Córdoba and Santa Fe. However, this reflects the distribution of the population in our country and the areas with highest COVID-19 incidence [2]. Less populated provinces were also represented and, as expected, these provinces contributed fewer patients. This is the biggest cohort of patients with rheumatic diseases and SARS-CoV-2 infection in our country and data from patients from all over Argentina have been included, considering sociodemographic and economic characteristics. Second, patients with an immunosuppressive condition could have been hospitalized even without presenting moderate or severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly at the beginning of the pandemic when information about their evolution and treatment was scarce. Notably, in this cohort, 43% of the hospitalized patients did not require oxygen supplementation. For this reason, more robust outcomes, like severe oxygen requirements and mortality, were also analyzed. Third, since only rheumatologists participated in this registry, no control group was included, only allowing indirect comparisons with the general population from previously published data. In addition, since some of the data was collected during the lockdown asymptomatic or mild cases could be underreported.

To conclude, unmodifiable, well-known risk factors like age and male gender, along with the presence of comorbidities, were related to poor COVID-19 outcomes in patients with rheumatic diseases. Hospitalizations were associated with socioeconomic factors related to social inequality, including ethnicity and public health insurance. Finally, patients with high disease activity and those receiving glucocorticoids or rituximab at the time of infection were more likely to have a poor COVID-19 outcome.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all the investigators for their participation across the country for their ongoing support of the registry. The authors are deeply grateful to Leonardo Grasso for providing expert assistance with the ARTHROS-web software and Leandro Cino for his contribution in the registry management tasks.

Appendix List of SAR-COVID investigators

Veronica Saurit

Ingrid Petkovic

Roberto Miguel Baez

Guillermo Pons-Estel

Yohana Tissera

Sofía Ornella

Ida Elena Exeni

Cecilia Pisoni

Vanessa Castro Coello

Guillermo Berbotto

Maria Jezabel Haye Salinas

Edson Velozo

Alvaro Andres Reyes Torres

Romina Tanten

Marcos David Zelaya

Carla Gobbi

Carla Gimena Alonso

Maria Severina

Florencia Vivero

Paula Alba

Karina Cogo

Gelsomina Alle

Mariana Pera

Romina Nieto

Micaela Cosatti

Cecilia Asnal

Dora Pereira

Juan Alejandro Albiero

Verónica Gabriela Savio

Federico Nicolas Maldonado

Maria Julieta Gamba

Noelia Germán

Andrea Baños

Josefina Gallino Yanzi

Maria Soledad Gálvez Elkin

Julieta Silvana Morbiducci

María Victoria Martire

Hernan Maldonado Ficco

Maria Marcela Schmid

Jaime Villafane

Maria De Los Angeles Correa

María Alejandra Medina

María Alejandra Cusa

Julia Scafati

Santiago Eduardo Agüero

Nicolás Martín Lloves Schenone

Ivana Romina Rojas Tessel

Rodolfo Perez Alamino

Aixa Lucia Mercé

Maria De La Vega

Verónica Bellomio

Leandro Carlevaris

Jonatan Marcos Mareco

Rosa María Figueroa

Maria Alicia Lazaro

Mercedes García

Maria Isabel Quaglia

Luciana González Lucero

Lorena Takashima (1er Pac)

Marina Laura Werner

Fabian Risueño

Natalia Lili Cucchiaro

Ana Bertoli

Gisela Pendon

Gustavo Fabián Rodriguez Gil

Pablo Finucci Curi

Laura Raiti

Andrea Belen Gomez Vara

Luciana Casalla

Eugenia Picco

Leila Mariana Muñoz

Maria Elena Calvo

Diana Marcela Castrillon

Catalina Gómez

Mercedes Cecilia Cordoba

Camila Rosario Reyes Gómez

Brian Manases Roldan

Cristina Amitrano

Carla Matellan

Sidney Soares De Souza

Florencia Rodriguez

Carolina Aeschlimann

Vicente Juarez

César Graf

Marianela Eliana Mauri

Cecilia Romeo

Elisa Novatti

Maria Natalia Tamborenea

Raúl Paniego

Malena Viola

Vanesa Cosentino

Sandra Petruzzeli

Zaida Noemi Bedran

Sebastián Moyano

Tatiana Barbich

Silvana Conti

Carla Maldini

Maria Daniela Alonso

María Victoria Borgia

Ana Carolina Ledesma

Maria Luz Martin

Boris Kisluk

Susana Isabel Pineda

Natalia Agustina Herscovich

Leticia Ibañez Zurlo

Elda Rossella Tralice

Dora Lia Vasquez

Natalia Morales

Mónica Patricia Diaz

Hernan Ariel Molina Merino

Rosana Gallo

Jessica Luciana Tomas

Anibal Alba

Graciela Gómez (Instituto Lanari)

Gisela Subils

Adriana Testi

Gisele Verna

Maria Eugenia Bedoya

Victor Yohena

Debora Guaglionone

Jonathan Eliseo Rebak

Maria Mercedes Croce

Carolina Dieguez

Mara Guinsburg

Santiago Catalán Pellet

Pablo Maid

Sabrina Porta

Norberto Javier Quagliato

Sabrina Solange De La Vega Fernandez

Emilio Buschiazzo

José Luis Velasco Zamora

María Silvina Perez Rodríguez

Federico Martin Paniego

Maria Lourdes Mamani Ortega

Graciela Vanesa Betancur

Rosa Serrano

Maria Sol Castaños Menescardi

Cinthya Retamozo

Cecilia Goizueta

Ana Quinteros

Fernanda Abadie

Ignacio Carrillo

Fernanda Guzzanti

Author contribution

All authors listed in this manuscript made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and were involved in drafting or revising this article critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published. A list of all the SAR-COVID registry sub-investigators is included in the Appendix.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: SAR-COVID, as a strategic registry from the Argentine Society of Rheumatology, has received unrestricted research grants to carry out this project from Pfizer, AbbVie, and Elea Phoenix. In addition, two grants from the International League of Associations of Rheumatology have been obtained.

Data availability

All data and materials generated and analyzed during the current study belong to the SAR-COVID registry and the Argentine Society of Rheumatology. They are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The authors declare that all relevant data is included in the article and its supplementary information files. More information about the registry is available in https://www.unisar.reumatologia.org.ar/registros_sarcovid.php.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study is being conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH), the ethical principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki, the law 3301/09, and local guidelines. Personal identification data was kept anonymous. An independent ethics committee approved the protocol and the informed consent form (Comité de Ética Dr Claude Bernard – SARCOVID.20200526.16.PI, June 8, 2020).

Consent to participate

All patients signed the corresponding informed consent form to participate in this registry.

Consent for publication

Individuals provided consent for the publication of their data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: SAR-COVID is a multi-sponsor registry, where Pfizer, Abbvie, and Elea Phoenix provided unrestricted grants. None of them participated or influenced the development of the project, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report. They do not have access to the information collected in the database.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Carolina A. Isnardi, Email: carolina.isnardi@reumatologia.org.ar

the S. A. R.–COVID Registry Investigators:

Veronica Saurit, Ingrid Petkovic, Roberto Miguel Baez, Guillermo Pons-Estel, Yohana Tissera, Sofía Ornella, Ida Elena Exeni, Cecilia Pisoni, Vanessa Castro Coello, Guillermo Berbotto, Maria Jezabel Haye Salinas, Edson Velozo, Alvaro Andres Reyes Torres, Romina Tanten, Marcos David Zelaya, Carla Gobbi, Carla Gimena Alonso, Maria Severina, Florencia Vivero, Paula Alba, Karina Cogo, Gelsomina Alle, Mariana Pera, Romina Nieto, Micaela Cosatti, Cecilia Asnal, Dora Pereira, Juan Alejandro Albiero, Verónica Gabriela Savio, Federico Nicolas Maldonado, Maria Julieta Gamba, Noelia Germán, Andrea Baños, Josefina Gallino Yanzi, Maria Soledad Gálvez Elkin, Julieta Silvana Morbiducci, María Victoria Martire, Hernan Maldonado Ficco, Maria Marcela Schmid, Jaime Villafane, Maria de los Angeles Correa, María Alejandra Medina, María Alejandra Cusa, Julia Scafati, Santiago Eduardo Agüero, Nicolás Martín Lloves Schenone, Ivana Romina Rojas Tessel, Rodolfo Perez Alamino, Aixa Lucia Mercé, Maria De la Vega, Verónica Bellomio, Leandro Carlevaris, Jonatan Marcos Mareco, Rosa María Figueroa, Maria Alicia Lazaro, Mercedes García, Maria Isabel Quaglia, Luciana González Lucero, Lorena Takashima, Marina Laura Werner, Fabian Risueño, Natalia Lili Cucchiaro, Ana Bertoli, Gisela Pendon, Gustavo Fabián Rodriguez Gil, Pablo Finucci Curi, Laura Raiti, Andrea Belen Gomez Vara, Luciana Casalla, Eugenia Picco, Leila Mariana Muñoz, Maria Elena Calvo, Diana Marcela Castrillón, Catalina Gómez, Mercedes Cecilia Córdoba, Camila Rosario Reyes Gómez, Brian Manases Roldán, Cristina Amitrano, Carla Matellan, Sidney Soares de Souza, Florencia Rodriguez, Carolina Aeschlimann, Vicente Juarez, César Graf, Marianela Eliana Mauri, Cecilia Romeo, Elisa Novatti, Maria Natalia Tamborenea, Raúl Paniego, Malena Viola, Vanesa Cosentino, Sandra Petruzzeli, Zaida Noemi Bedran, Sebastián Moyano, Tatiana Barbich, Silvana Conti, Carla Maldini, Maria Daniela Alonso, María Victoria Borgia, Ana Carolina Ledesma, Maria Luz Martin, Boris Kisluk, Susana Isabel Pineda, Natalia Agustina Herscovich, Leticia Ibañez Zurlo, Elda Rossella Tralice, Dora Lia Vasquez, Natalia Morales, Mónica Patricia Díaz, Hernan Ariel Molina Merino, Rosana Gallo, Jessica Luciana Tomas, Anibal Alba, Graciela Gómez, Gisela Subils, Adriana Testi, Gisele Verna, Maria Eugenia Bedoya, Victor Yohena, Debora Guaglionone, Jonathan Eliseo Rebak, Maria Mercedes Croce, Carolina Dieguez, Mara Guinsburg, Santiago Catalán Pellet, Pablo Maid, Sabrina Porta, Norberto Javier Quagliato, Sabrina Solange De La Vega Fernandez, Emilio Buschiazzo, José Luis Velasco Zamora, María Silvina Pérez Rodríguez, Federico Martin Paniego, Maria Lourdes Mamani Ortega, Graciela Vanesa Betancur, Rosa Serrano, Maria Sol Castaños Menescardi, Cinthya Retamozo, Cecilia Goizueta, Ana Quinteros, Fernanda Abadie, Ignacio Carrillo, and Fernanda Guzzanti

References

- 1.Furst DE. The risk of infections with biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:327–346. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auyeung TW, Lee JS, Lai WK, et al. The use of glucocorticoids as treatment in SARS was associated with adverse outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. J Infect. 2005;51:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hui DS. Systemic corticoid therapy may delay viral clearance in patients with middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:700–701. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201712-2371ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misra DP, Agarwal V, Gasparyan AY, Zimba O. Rheumatologists´ perspective on coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) and potential therapeutic targets. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:2055–2062. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05073-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Favalli EG, Ingegnoli F, De Lucia O, Cincinelli G, Cimaz R, Caporali R. COVID-19 infection and rheumatoid arthritis: faraway, so close! Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102523. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schönfeld D, Arias S, Bossio JC, Fernández H, Gozal D, Pérez-Chada D. Clinical presentation and outcomes of the first patients with COVID-19 in Argentina: results of 207079 cases from a national database. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0246793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strangfeld A, Schäfer M, Gianfrancesco MA, et al. (2021) Factors associated with COVID-19-related death in people with rheumatic diseases: results from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis 0:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Gianfrancesco M, Hyrich KL, Al-Adely S, et al. (2020) Characteristics associated with hospitalization for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis 0:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Isnardi CA, Gómez G, Quintana R, et al. Características epidemiológicas y desenlaces de la infección por SARS-CoV-2 en pacientes con patologías reumáticas: Primer reporte del registro argentino SAR-COVID. Rev Arg Reumatol. 2021;32:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Méndez H. Sociedad y estratificación. Método Graffar-Méndez Castellano. Caracas: Fundacredesa; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Word Health Organization (2020). COVID-19 Therapeutic Trial Synopsis. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/covid-19-therapeutic-trial-synopsis. Accessed 17 Nov 2021

- 12.Leveau CM. Variaciones espacio-temporales de la mortalidad por COVID-19 en barrios de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Rev Argent Salud Pública. 2021;13:e27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marinhoa PRD, Cordeiro GM, Coelho HFC, Brandão SCS. Covid-19 in Brazil: a sad scenario. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021;58:51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villalobos Dintrans P, Castillo C, de la Fuente F, Maddaleno M. COVID-19 incidence and mortality in the Metropolitan Region, Chile: time, space, and structural factors. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0250707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mena GE, Martinez PP, Mahmud AS, Marquet PA, Bukeeand CO, Santillana M. Socioeconomic status determines COVID-19 incidence and related mortality in Santiago. Chile Science. 2021;372:1–8. doi: 10.1126/science.abg5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gianfrancesco MA, Leykina LA, Izadi Z, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with COVID-19 outcomes in rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance Physician Registry. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:374–380. doi: 10.1002/art.41567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izadi Z, Gianfrancesco MA, Schmajuk G, et al. Environmental and societal factors associated with COVID-19-related death in people with rheumatic disease: an observational study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(22)00192-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bower H, Frisell T, Di Giuseppe D, et al. (2021) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on morbidity and mortality in patients with inflammatory joint diseases and in the general population: a nationwide Swedish cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 0:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Regierer AC, Hasseli R, Schäfer M, et al. TNFi is associated with positive outcome, but JAKi and rituximab are associated with negative outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with RMD. RMD Open. 2021;7:e001896. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sparks JA, Wallace ZS, Seet AM, et al. (2021) Associations of baseline use of biologic or targeted synthetic DMARDs with COVID-19 severity in rheumatoid arthritis: results from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician registry. Ann Rheum Dis 0:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Cordtz R, Lindhardsen J, Soussi BG, et al. (2021) Incidence and severeness of COVID-19 hospitalization in patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease: a nationwide cohort study from Denmark. Rheumatology (Oxford). 60:SI59-SI67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Serling-Boyd N, D'Silva KM, Hsu TY, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes among patients with rheumatic diseases 6 months into the pandemic. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:660–666. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Silva KM, Jorge A, Cohen A, et al. COVID-19 outcomes in patients with systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases compared to the general population: a US multicenter, comparative cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:914–920. doi: 10.1002/art.41619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin YH, Shin JI, Moon SY, et al. Autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases and COVID-19 outcomes in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e698–e706. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00151-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Topless RK, Phipps-Green A, Leask M, et al. Gout, rheumatoid arthritis, and the risk of death related to coronavirus disease 2019: an analysis of the UK Biobank. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2021;3:333–340. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.England BR, Roul P, Yang Y, et al. Risk of COVID-19 in rheumatoid arthritis: a national Veterans Affairs matched cohort study in at-risk individuals. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:2179–2188. doi: 10.1002/art.41800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ministerio de salud de Argentina. (2021) Reporte de situación COVID-19. IOP Publishing Ministerio de salud de Argentina https://www.argentina.gob.ar/coronavirus/informes-diarios/reportes/julio2021. Accessed 24 April 2022.

- 28.Marques C, Kakehasi AM, Gomides APM, et al. A Brazilian cohort of patients with immuno-mediated chronic inflammatory diseases infected by SARS-CoV-2 (ReumaCoV-Brasil Registry): protocol for a prospective, observational study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9:e24357. doi: 10.2196/24357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marques CDL, Kakehasi AM, Pinheiro MM, et al. High levels of immunosuppression are related to unfavorable outcomes in hospitalized patients with rheumatic diseases and COVID-19: first results of ReumaCoV Brasil registry. RMD Open. 2021;7:e001461. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ugarte-Gil MF, Marques CDL, Alpizar-Rodriguez D, et al. (2020) Characteristics associated with Covid-19 in patients with rheumatic disease in Latin America: data from the Covid-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. IOP Global Rheumatology by PANLAR web. https://www.globalrheumpanlar.org/node/254. Accessed 31 August 2022.

- 31.Landewé RBM, Kroon FPB, Alunno A, et al. (2022) EULAR recommendations for the management and vaccination of people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in the context of SARS-CoV-2: the November 2021 update. Ann Rheum Dis. annrheumdis-2021–222006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.ACR COVID-19 Vaccine Clinical Guidance Task Force. (2022) COVID-19 Vaccine Clinical Guidance Summary for Patients with Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases. Version 5. Revised February 2, 2022. IOP American College of Rheumatology web. https://www.rheumatology.org/Portals/0/Files/COVID-19-Vaccine-Clinical-Guidance-Rheumatic-Diseases-Summary.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials generated and analyzed during the current study belong to the SAR-COVID registry and the Argentine Society of Rheumatology. They are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The authors declare that all relevant data is included in the article and its supplementary information files. More information about the registry is available in https://www.unisar.reumatologia.org.ar/registros_sarcovid.php.