Abstract

Purpose

Proton therapy use for breast cancer has grown due to advantages in coverage and potentially reduced late toxicities compared with conventional radiation therapy. We aimed to provide recommendations for robustness criteria, daily imaging, and quality assurance computed tomography (QA CT) frequency for these patients.

Methods and Materials

All patients treated for localized breast cancer at the Johns Hopkins Proton Center between November 2019 and February 2022 were eligible for inclusion. Daily shift information was extracted and examined through control charts. If an adaptive plan was used, the time to replan was recorded. Three and 5 mm setup uncertainty was used to calculate robustness. Robust evaluation of QA CTs was compared with initial robustness range for breast/chest wall and lymph node target coverage.

Results

Sixty-six patients were included: 19 with intact breast, 25 with non-reconstructed chest wall, and 22 with chest wall plus expanders or implants. Sixteen percent, 13%, and 41% of breast, chest wall, and expander/implant patients had a replan. Only patients with expanders or implants required 2 adaptive plans. Daily shift data showed large variation and did not correlate with plan adaptation. Patients without adaptive plans had QA CTs with dose-volume histogram metrics within robustness more frequently than those with adaptive plans. Using 3 mm robustness for patients who did not require an adaptive plan, 91% to 100% of patients had QA CTs within robustness, while 55% to 60% of patients with an adaptive plan had QA CTs within robustness for the axilla, internal mammary nodes, and supraclavicular nodes. Five millimeter setup uncertainty did not significantly improve this.

Conclusions

We recommend using daily cone beam CT because of the large variation in daily setup with 3 mm setup uncertainty in robustness analysis. If daily cone beam CT imaging is not available, then larger setup uncertainty should be used. Two QA CTs should be conducted during treatment if the patient has expanders or implants; otherwise, one QA CT is sufficient.

Introduction

Proton therapy use has been consistently growing since initial Food and Drug Administration clearance in 1988, with 38 current operating centers within the United States and more currently under development.1 Specifically, proton therapy use for locally advanced breast cancer has seen a rapid rise because of this increase in access and the advantages in coverage and potential advantages in reduced late toxicities with proton therapy compared with conventional radiation therapy.2, 3, 4, 5 Conventional photon radiation therapy for locally advanced breast cancer often requires compromise between coverage of the breast or chest wall and lymph nodes with radiation exposure to the lung and heart. Comparatively, proton therapy may have improved target coverage while minimizing dose to nearby organs at risk (OARs) in selected cases.2, 3, 4,6,7

Unlike conventional radiation therapy that assesses target coverage using planning target volumes, proton therapy plans are evaluated on the nominal plan and under robustness scenarios.8 These robustness scenarios encompass both range uncertainty and setup uncertainty. Additionally, as proton therapy plans are very sensitive to setup or body habitus changes, on-treatment quality assurance computed tomography (QA CT) scans are taken at various intervals over the course of treatment. These QA CTs assess if the current plan maintains acceptable coverage and OAR doses or if an adaptive plan is needed. Selecting appropriate robustness criteria for planning is crucial, as using too small of a setup uncertainty value risks requiring adaptive plans while using too large of a setup uncertainty value may diminish OAR sparing.

Despite the growing use of proton therapy for breast cancer, there are few recommendations for planning and treatment. The Particle Therapy Co-Operative Group recently published guidelines for proton therapy that focus on clinical evidence for the use of protons in breast cancer, focusing on clinical indications, target delineation, dosimetric objectives, and toxicity.2 However, there are no published recommendations for robustness criteria, QA CT frequency, or treatment imaging needed for treatment planning and daily treatment. In this study we aimed to fill this gap in practical guidance.

Methods and Materials

Study participants

All patients treated for localized breast cancer at the Johns Hopkins Proton Therapy Center between November 2019 and February 2022 were eligible for inclusion. Patients were excluded if the whole breast or chest wall was not treated with proton therapy or if the proton therapy plan was not completed and the patient was treated with photons for the remaining fractions. This work was conducted with a waiver of informed consent under Johns Hopkins institutional review board approval. All patients were treated using a ProBeat compact-gantry pencil beam scanning proton therapy system (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) with a gantry-mounted cone beam CT (CBCT). Plans were created using 2 to 3 beams with a 4-cm range shifter using Raystation (version 11a; RaySearch Laboratories, Stockholm, Sweden). Treatment plans were optimized robustly with 3 or 5 mm setup uncertainty. All plans were optimized with range uncertainty of 3.5%. Single-field optimization planning approaches were preferred but multifield optimization was employed to achieve improved normal tissue sparing for some cases when deemed clinically beneficial. Final dose was computed using Monte Carlo with 0.5% statistical uncertainty. All dose reported is using a constant relative biological effectiveness of 1.1.

Dosimetric analysis

Patients were classified into three categories: (1) intact breast, (2) non-reconstructed chest wall, and (3) reconstructed chest wall with expanders or implants. These categories were used for analysis of QA CT frequency and daily shift data. The frequency of plan adaptation was recorded to examine the adequate QA CT frequency. If an adaptive plan was created, then the number of fractions from the start of treatment until the adaptive plan started was recorded (ie, the number of fractions of the initial plan actually delivered for treatment). For each patient, daily shifts at the treatment machine (superior-inferior, left-right, anterior-posterior, roll, pitch, and yaw) from daily CBCT images were recorded.

Patients requiring adaptive plans and those who did not were analyzed as separate cohorts to assess the effect of the time between surgery and simulation and the proper robustness criteria. For the robustness analysis, only patients who had at least two QA CTs and were not archived out of the treatment planning system were included in the analysis. To clarify, the patients who had been archived did not have accessible Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine data. Each patient's nominal initial plan was calculated with 3 and 5 mm robustness. The target coverage for each QA CT was evaluated if it was within the robustness criteria (eg, the D95% of the breast as calculated on the QA CT was evaluated if it was within the range of values of the D95% for 3/5 mm robustness on the nominal plan). The evaluated metrics were based on Johns Hopkins internal clinical goals, which included breast/chest wall D95% and V53.5 Gy, axillary lymph nodes D95%, internal mammary nodes (IMNs) D90%, and supraclavicular lymph nodes D95%. Lymph node coverage was only assessed if they were targeted within the treatment plan. A cutoff of 1 Gy cumulatively was used to determine whether a QA CT's dose coverage was clinically meaningfully outside of the robustness calculated on the initial plan. For example, if a QA CT calculated a breast D95% that was outside of the 3 or 5 mm robustness results but within 1 Gy from the minimum or maximum from the robustness range, then it was counted as the QA CT falling within the robustness criteria. The percentage of patients with QA CTs failing to be within the robustness criteria was compared for patients with and without adaptive plans.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the daily shifts over the course of treatment, control charts were created for each of the three categories (breast, non-reconstructed chest wall, and reconstructed chest wall with expanders/implants) separately for daily shifts. Statistical process control charts are used to show how a process changes over time to determine whether the process variation is consistent.9 Control chart limits were calculated for each shift direction by average ± 3 × standard deviation (SD).

To assess the effect of the time between surgery and simulation, a one-sided Student t test was conducted on the time from surgery to simulation between patients with and without an adaptive plan. R (version 4.1.0) was used for all statistical analysis.10 A one-sided t test was chosen for this test as we were specifically interested in determining whether an adaptive plan was associated with a shorter time between surgery and simulation, not just if the two groups were different. Results of this one-tailed test were significant at the 5% level (P < .05).

To assess if the percent of passing QA CTs was different between the 3- and 5-mm robustness analyses, a two-sided paired Wilcoxon rank sum test was conducted on the passing rate for the dose-volume histogram (DVH) metrics extracted. Results of this two-tailed test were significant at the 5% level (P < .05).

Results

Sixty-six patients were included in this study, including 19 intact breast patients, 25 non-reconstructed chest wall patients, and 22 patients with expanders or implants. Fifty-three patients had a prescription of 200 cGy × 25 fractions, 1 patient had a prescription of 200 cGy × 23 fractions, 1 patient had a prescription of 200 cGy × 27 fractions, and 11 patients had a prescription of 180 cGy × 28 fractions. If a patient had a boost, it was not analyzed within this study. It was observed that if a patient was a physician's first proton therapy patient then the patient was adapted, which could affect the analysis of QA CT frequency, therefore, two non-reconstructed chest wall patients were removed from analysis. Table 1 summarizes the adaptive plan rate and time scale for each of the three categories. Breast and non-reconstructed chest wall patients had a low replan rate of 16% or less, while patients with expanders or implants were replanned over 40% of the time. Additionally, breast and non-reconstructed chest wall patients had a longer time to replan compared with patients with patients with expanders or implants when examining the average time to replan; however, no statistical analysis could be performed because of the small number of patients requiring an adaptive plan in the breast and non-reconstructed chest wall groups. All patients who required a second adaptive plan (n = 4) were patients with expanders or implants or a physician's first proton therapy patient. The average time from the start of treatment until the second adaptive plan was 14.3 fractions (range, 10-20 fractions; SD, 3.8 fractions).

Table 1.

Breast, non-reconstructed chest wall, and reconstructed chest wall with expanders or implants replan rates

| Number of patients requiring replan | Total number of patients | Replan rate | Average fractions to replan (minimum to maximum, standard deviation) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | 3 | 19 | 16% | 16 (13-19, 2.4) |

| Chest wall | 3 | 23 | 13% | 11 (9-14, 2.2) |

| Implants | 9 | 22 | 41% | 6.4 (3-14, 3.2) |

| Total | 15 | 64 | 23% | 9.3 (3-19, 4.8) |

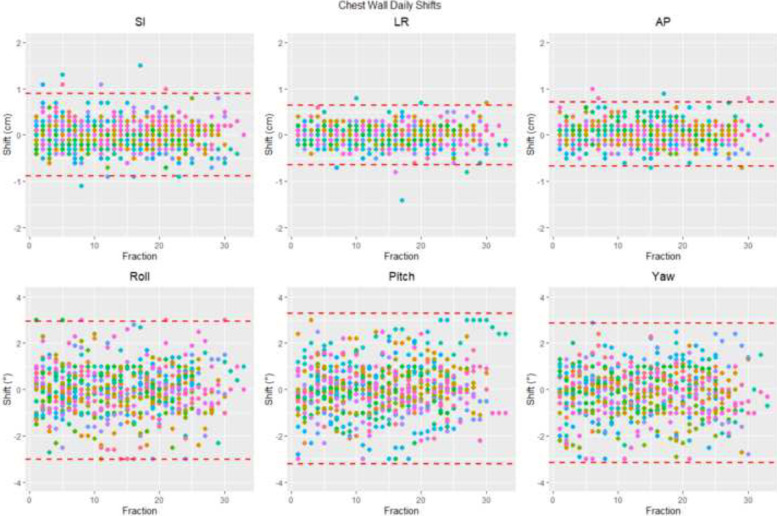

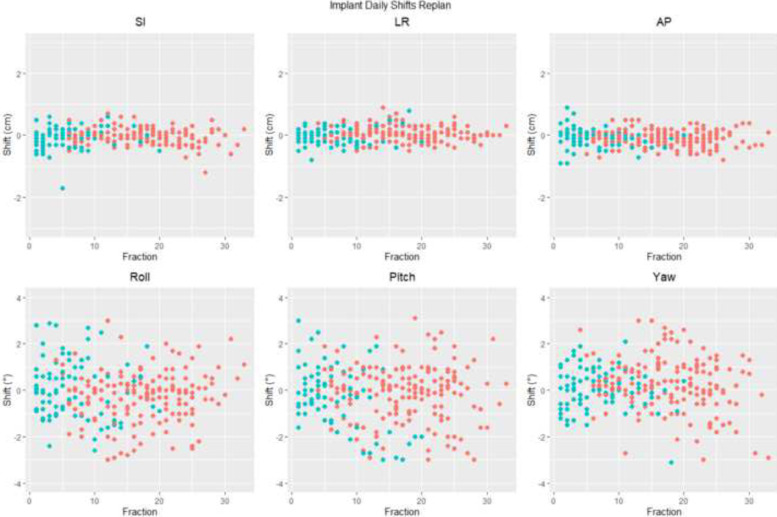

Figure 1 shows the daily shifts for each non-reconstructed chest wall patient. Plots for breast and expander/implant patients are similar and included in Figure E1 and E2. It is evident that daily shifts can be large and can vary over the course of treatment for a given patient. The control chart limits can give an indication at the machine that if a shift is above the limit, then caution should be applied as this is outside normal variation. For roll, pitch, and yaw, these are around 3⁰, which are not useful within our clinic as adjustments in these directions are limited to 3⁰. As shown in Fig. 1, cardinal direction shift control chart limits for non-reconstructed chest wall patients are ±0.9 cm superior-inferior, ±0.6 cm left-right, and ±0.7 cm anterior-posterior. Figure 2 demonstrates that the daily shift variation is not related to a plan needing to be adapted. The same variation in each shift direction is observed before and after a replan.

Figure 1.

Daily shifts for setup from cone beam computed tomography images for non-reconstructed chest wall patients in superior-inferior (SI), left-right (LR), anterior-posterior (AP), roll, pitch, and yaw directions. Each patient is represented by a different color. The red dashed lines represent the control chart limits for that shift direction.

Figure 2.

Daily shift data for patients with breast implants before and after a replan. The blue dots represent the initial plan being used within the clinic and the red dots represent the adaptive plan being used in the clinic. Abbreviations: AP = anterior-posterior; LR = left-right; SI = superior-inferior.

Forty-nine patients had treatment without needing an adaptive plan. The average time between surgery and simulation was 82 days (range, 11-207 days; SD, 56.8 days). Seventeen patients required an adaptive plan during the course of their treatment and had an average time between surgery and simulation of 55 days (range, 18-188 days; SD, 43.4 days). The one-sided t test showed that the time between surgery and simulation is significantly smaller for patients who require an adaptive plan (P = .029).

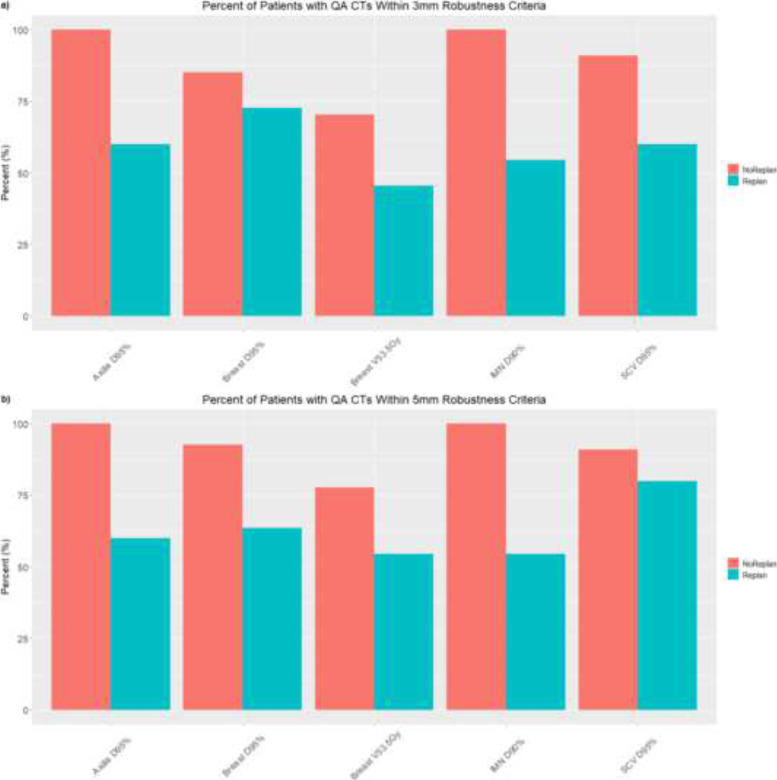

Thirty-eight patients were eligible for robustness analysis. Twenty-seven patients had no adaptive plan and 11 patients had an adaptive plan. Thirty-one patients had a prescription of 200 cGy × 25 fractions and 7 patients had a prescription of 180 cGy × 28 fractions. Figure 3 shows the percentage of patients who had QA CTs where the DVH evaluation metrics were within the robustness calculated on the initial plan using either 3 or 5 mm setup uncertainty. For every DVH metric evaluated, the patients without adaptive plans had more QA CTs that were within robustness compared with patients who had an adaptive plan. Lymph node coverage had the largest difference. Under 3 mm robustness for patients who did not have an adaptive plan, all patients’ QA CTs were within the robustness for the axilla and IMN, and 91% of patients had QA CTs within robustness for the supraclavicular lymph nodes. Eighty-five percent and 70% of patients had QA CTs within robustness for the breast D95% and breast V53.5 Gy, respectively. However, for patients with an adaptive plan, 60%, 55%, 60%, 73%, and 45% of patients had QA CTs within robustness for the axilla, IMN, supraclavicular lymph nodes, breast D95%, and breast V53.5 Gy, respectively. Similarly, under 5 mm robustness for patients without an adaptive plan, 100%, 100%, 91%, 92%, and 78% of patients had QA CTs within robustness for the axilla, IMN, supraclavicular lymph nodes, breast D95%, and breast V53.5 Gy, respectively. In patients with an adaptive plan, 60%, 55%, 80%, 64%, and 55% of patients had QA CTs within robustness for the axilla, IMN, supraclavicular lymph nodes, breast D95%, and breast V53.5 Gy, respectively. These results combined demonstrate that under 3 mm robustness, almost all patients who did not have an adaptive plan had DVH metrics for their breast/chest wall and nodal targets within robustness, while only about half of patients with an adaptive plan had these DVH metrics within robustness. The Wilcoxon signed rank test of the DVH metrics between the 3 and 5 mm robustness showed that there was not a significant difference between the two robustness scenarios (P = .28). Therefore, 3 mm robustness represents a good setup uncertainty criterion as most patients without adaptive plans were within this criterion, while 5 mm did not significantly change the percentages for DVH metrics but would reduce OAR sparing if used in treatment planning.

Figure 3.

Percent of patients with quality assurance computed tomography (QA CT) scans within (A) 3 mm or (B) 5 mm setup uncertainty for robustness for breast and lymph node targets as calculated on original plan.

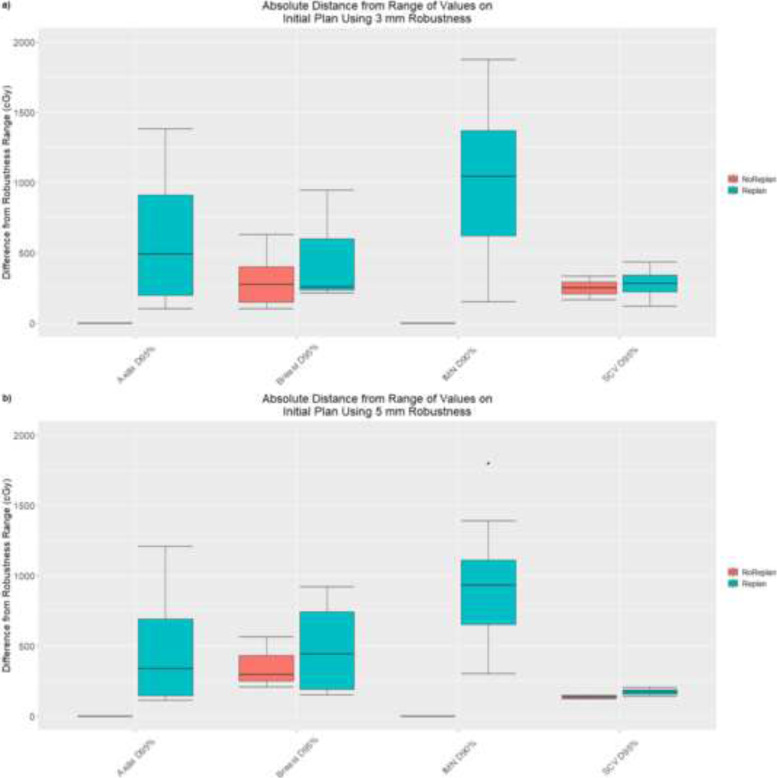

For patients who had a QA CT that fell outside of the range of DVH values calculated on the initial plan using the different robustness criteria, the distance of the DVH value on the QA CT to the robustness range was calculated. Figure 4 shows this distribution of these delta values for patients who did or did not require an adaptive plan for the different robustness criteria. The range of values is much larger for the patients who required an adaptive plan. For the breast D95% and supraclavicular lymph nodes D95%, the median difference is about the same between patients with and without an adaptive plan for the 3 mm robustness, but for 5 mm robustness, the median difference is larger for patients with an adaptive plan. The largest difference is observed between the two groups of patients for the axilla D95% and IMN D90%, as all patients who did not have a replan had QA CT DVH values within the robustness range. For 3 mm setup uncertainty, the median breast V53.5 Gy difference from the robustness range was 0.3 cm3 (range, 0.03-3.7 cm3) and 2.8 cm3 (range, 0.01-28.3 cm3) for patients without and with an adaptive plan, respectively. For 5 mm setup uncertainty, this difference was 0.5 cm3 (range, 0.02-10.2 cm3) and 2.6 cm3 (range, 0.04-22.6 cm3) for patients without and with an adaptive plan, respectively.

Figure 4.

Delta values for patient's quality assurance computed tomography scans that were outside of the robustness range for (A) 3 mm setup uncertainty and (B) 5 mm setup uncertainty. The distance that the dose-volume histogram metric was from the range is shown in red for patients who did not have an adaptive plan and in blue for patients who did have an adaptive plan.

Discussion

From over two years of treating breast cancer patients with proton therapy using daily CBCT, we were able to analyze practical data for adaptive plans based on the particular treatment type (ie, breast, non-reconstructed chest wall, reconstructed chest wall with expanders or implants), which can then be translated to QA CT necessities, daily shifts for patients and the relationship with adaptive plans, and different robustness criteria. We suggest the following recommendations: (1) patients with expanders or implants should have two QA CTs acquired on the first day and second week of treatment, (2) daily CBCTs should be acquired with 3 mm used for setup uncertainty, and (3) if daily CBCT is unavailable, larger uncertainty should be used at the time of planning.

Based on the analysis of replan rate and time to replan for each category, we recommend the following: one QA CT within the first week for breast and non-reconstructed chest wall patients and two QA CTs for patients with expanders or implants or physicians’ first proton therapy patients. The two QA CTs should be the first day of treatment and around the second week of treatment. The recommendations for the first QA CT come from the minimum time to adaptive plan (Table 1), so the need of an adaptive plan would be caught in time for planning to be completed without too many fractions delivered of a suboptimal plan for the patient because of the anatomic or setup changes. We recommend patients with implants or a physicians’ first proton therapy patient receive a second QA CT. This is because in our data we determined these patients were the only ones who required a second adaptive plan. The recommendation of the timing for this second QA CT is based on the observed time interval from the start of treatment to the second adaptive plan. Additionally, the time between surgery and simulation was shown to significantly influence whether patients required an adaptive plan or not; however, this time is often not controllable and is determined by outside factors such as surgical recovery and use of systemic therapies. Therefore, patients who have a short time between surgery and simulation should have additional QA CTs, or special attention should be paid to CBCT images to indicate if additional QA CTs are needed.

The control charts demonstrated that setup can vary over a large range daily with no trends for each patient and no correlation with needing an adaptive plan. Therefore, for daily treatment, we recommend daily CBCT given the large daily shifts that were observed that were not influenced by a patient having an adaptive plan. However, not all facilities may be capable of daily CBCT, in which case, larger robustness criteria should be used on the initial nominal plan to account for the daily setup variation that will not be corrected by 3-dimensional (3D) imaging. Liang et al11 found that breast target D95 was well maintained for various image registration techniques, except for patients where the bony anatomy was more than 2⁰ off or patients with breast edema. Daily CBCT or other 3D techniques allow better visualization of these changes.

The robustness analysis of DVH metrics on QA CTs showed similar results for both 3 and 5 mm setup uncertainty. Using higher setup uncertainty for robustness will often cause nearby OARs to have increased dose to maintain target coverage under uncertainty scenarios. Therefore, as results were similar between the two robustness criteria analyzed, 3 mm is sufficient. However, as mentioned previously, larger setup uncertainty for robustness criteria should be considered when daily 3D imaging is not available because of increased daily setup variations.

The proposed recommendations are subject to several important limitations, including the small cohort in this preliminary study. This is a single institution study, and future studies from outside institutions should be conducted to corroborate these results. It should be noted that robustness was evaluated using QA CTs. The differences in setup observed on the QA CT may not be indicative of how the patient was treated and must be carefully monitored and minimized through immobilization. Future work will use daily CBCT to evaluate robustness and may offer more insight to delivered dose. Additionally, not all patients could be included in the robustness assessment as only more recently treated patients were still accessible within the treatment planning system. However, even with these limitations, practical recommendations for breast proton therapy can be drawn from this study, many of which have not yet been addressed in previously published guidelines.

Conclusion

As proton therapy is increasingly used for breast cancer treatment, we aimed to provide practical recommendations for treatment planning and daily treatment. We recommend using daily CBCT with 3 mm setup uncertainty in robustness analysis. If daily CBCT imaging is not available, then larger setup uncertainty should be used. If the patient has expanders or implants or a short time between surgery and simulation, then two QA CTs should be conducted during treatment, otherwise, one QA CT early in the treatment course is sufficient.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This work had no specific funding.

Disclosures: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data sharing statement: Research data are not available at this time.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.adro.2022.101069.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.The National Association for Proton Therapy. Homepage. Available at: https://www.proton-therapy.org/. Accessed April 18, 2022.

- 2.Mutter RW, Choi JI, Jimenez RB, et al. Proton therapy for breast cancer: A consensus statement from the Particle Therapy Cooperative Group Breast Cancer Subcommittee. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;111:337–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.05.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musielak M, Suchorska WM, Fundowicz M, Milecki P, Malicki J. Future perspectives of proton therapy in minimizing the toxicity of breast cancer radiotherapy. J Pers Med. 2021;11:410. doi: 10.3390/jpm11050410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kammerer E, Le Guevelou J, Chaikh A, et al. Proton therapy for locally advanced breast cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;63:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jimenez RB, Hickey S, DePauw N, et al. Phase II study of proton beam radiation therapy for patients with breast cancer requiring regional nodal irradiation. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2778. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corbin KS, Mutter RW. Proton therapy for breast cancer: Progress & pitfalls. Breast Cancer Manage. 2018;7:BMT06. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley JA, Mendenhall NP. Novel radiotherapy techniques for breast cancer. Ann Rev Med. 2018;69:277–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042716-103422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unkelbach J, Paganetti H. Robust proton treatment planning: Physical and biological optimization. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2018;28:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:458–464. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.6.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed April 18, 2022.

- 11.Liang X, Mailhot Vega RB, Li Z, Zheng D, Mendenhall N, Bradley JA. Dosimetric consequences of image guidance techniques on robust optimized intensity-modulated proton therapy for treatment of breast cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2020;15:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13014-020-01495-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.