Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a dramatic increase in telemedicine care delivery. This raises the question of whether the visit type affects the care provided to patients in the pediatric gastroenterology clinic. The aim of this study is to assess whether diagnostic, treatment, and outcome measures differ between telemedicine and in-person visits in patients seen in pediatric gastroenterology clinics for the chief complaint of abdominal pain.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients aged 0–22 who underwent their initial pediatric gastroenterology clinic visit, for abdominal pain, between March and September 2020 (n = 1769). The patients were divided into two groups: in-person or telemedicine. Clinical outcome measures were compared from the initial gastroenterology visit and followed for a total of 3 months.

Results

There was an increase number of images (M = 0.52 vs. 0.36, p < 0.001), labs (M = 4.87 vs. 4.05; p = 0.001), medications (M = 2.24 vs. 1.67; p < 0.001), and referrals (M = 0.70 vs. 0.54; p < 0.001) performed per visit in the in-person group. Electronic communications (3.97 vs. 5.12 p <0.003) was less frequent after in-person visits. There was no difference in number of procedures (M = 0.128 vs. 0.122, p = 0.718), emergency room visits (M = 0.037 vs. 0.017 p = 0.61), follow-up visits (M = 1.21 vs. 1.21 p = 0.922), or telephone encounters (M = 1.21 vs. 1.12 p = 0.35) between the two groups.

Conclusion

Telemedicine utilizes less resources while having comparable outcome measurements in children with a chief complaint of abdominal pain.

Keywords: Abdominal pain, telemedicine, telehealth, COVID-19, pediatric

Introduction

The majority of care provided to patients takes place in the outpatient setting. In pediatric gastroenterology (GI), outpatient medicine has traditionally included an in-person interaction between a provider, the patient, and caregivers. This traditional care model was upended in March 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic. Texas Children's Hospital, like many institutions, rapidly transitioned to video-based telemedicine visits until safety measures were implemented to allow in-person visits to resume. Once resumed, a hybrid model of care was implemented wherein both in-person and telemedicine visits were utilized (based upon patient preference and logistical parameters) to provide care.

Non-in-person visits are not a new concept and can be traced back to the 1800s.1 Telemedicine itself, although a more recent discovery, has been implemented in a multitude of specialties.2–8 Many of these specialties have tried to answer the question of whether or not there is a difference in care provided to patients based upon their visit type. In general pediatrics, Portnoy et al. demonstrated that children with asthma treated in-person versus by telemedicine had similar treatment outcomes in disease management.3 Similarly, McConnochie et al. found no difference between telemedicine and in-person care in common pediatric diagnoses.4 Finally in a meta-analysis conducted by Snoswell et al., the authors demonstrated that telemedicine can be equivalent and in some cases more effective than usual care.5 These studies suggest that in-person and telemedicine modalities lead to comparable treatment outcomes. However, another study by Raphael et al., compared telemedicine management of patients on home parenteral nutrition with historical controls and demonstrated a mixed picture, with a reduction in overall CLABSI rates but an increase in readmissions.6

In the field of pediatric GI, there have been limited studies that investigate the use of telemedicine in patient care. Stone et al. initially discussed the potential benefits of telemedicine prior to the pandemic; highlighting financial, communication, and time management improvements for both patients and providers.7 One study conducted by Lee et al. studied pediatric gastroenterologists’ opinions on telemedicine and demonstrated high perceived usefulness and satisfaction scores; however, it did not look at patient-specific measures.8 Love et al. conducted surveys of patients that demonstrated high perceived value and quality of care with telemedicine visits for the majority of patients.9

The most common chief complaint seen in outpatient pediatric GI clinics is abdominal pain. Abdominal pain can be the initial presentation of disease processes ranging from a functional disorder to acute appendicitis or even inflammatory bowel disease. Wallis et al. investigated abdominal pain in pediatric patients and noted that in fact 70% of children are never given a specific diagnosis and only 3% of laboratory tests and 20% of radiological tests resulted in a diagnosis being given.10 The lack of a definitive diagnosis (in most cases) and lack of standardized scoring system to assess severity leads to a wide variance in the number and type of diagnostic tests and treatments being performed for a particular patient. This makes abdominal pain an ideal complaint for this type of analysis. This study was a retrospective quasi-experimental cohort study, aimed at investigating whether visit type results in differences between the number of diagnostic tests ordered, treatments given, or outcomes measured in patients presenting to a pediatric GI clinic for a chief complaint of abdominal pain.

Methods

A structured query language (SQL) tool was used to extract information from the electronic medical records of pediatric patients cared for at the Texas Children's Hospital from March to September 2020. This data was retrospectively reviewed under an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol that was approved for that time period. Patients ranged in age from 0 to 22 years and were included in the study if they met the criteria of having an initial encounter for the chief complaint of abdominal pain. This population was split into two groups based upon the modality of their visit to the GI clinic: in-person or telemedicine (i.e. video-based). The choice of in-person or telemedicine visits was given to the patient and was determined solely on their preference (it is important to note that telemedicine visits did have a shorter scheduling time when compared to in-person visits). Patients seen (either via telemedicine or in-person) received diagnostic work-up and treatment at the sole discretion of their provider and there was not a “standard protocol” in place for the treatment of abdominal pain. Once the visit had been completed the patient would receive discharge instructions via email or printed (for in-person clinic visits), patients also had access to discharge instructions through their patient portal application Mychart. Visits led by an attending physician, GI fellow, or pediatric GI nurse practitioner were included in this study. Clinical information regarding age, sex, and race/ethnicity were also collected as self-reported in the electronic medical record. Once the patient had completed their initial GI visit, they were assessed for follow-up in the electronic medical record for 3 months following that initial encounter. Data were analyzed and split into three categories: diagnostic, treatment, and outcomes. Diagnostic orders were comprised of imaging studies (X-rays, ultrasonography, computerized tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging), laboratory orders (stool, urine, and blood-based studies), procedures (esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), colonoscopy), and referrals to other specialists within the TCH system; while treatments consisted of the number of distinct medications ordered. Outcome measures included emergency room encounters, follow-up GI visits, electronic communications (messages sent through the electronic medical record system), and telephone encounters (phone calls from the provider to the patient recorded in the electronic medical record).

Data were analyzed using R programming. Preliminary analyses were performed to detect subsample (i.e. age, sex, and race) differences, using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests (including correction for homogeneity of variance) for continuous dependent variables. For the primary analyses, a Levene's test was performed to determine if the variances were homogenous across groups for each outcome variable. Finally, either a standard t-test (for equal variances) or Welch's t-test (for unequal variances) was conducted between the two groups.

Results

In this study, 1769 patients were seen in a pediatric GI clinic for their initial visit with a chief complaint of abdominal pain. Of these encounters, 1131 were in-person and 638 were via telemedicine. Demographic information was statistically similar between the two groups and is listed in Table 1 (note that some patients did not list race/ethnicity and were not included in race/ethnicity comparison data).

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| In-person (%) | Telemedicine (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 11.6 | 11.3 | 0.14 |

| Sex | 0.41 | ||

| Male | 671 (59.3) | 392 (61.4) | |

| Female | 460 (40.7) | 246 (38.6) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.77 | ||

| White | 434 (43.0) | 270 (46.7) | |

| Hispanic (Non-White) | 390 (38.7) | 205 (35.5) | |

| African American | 122 (12.1) | 76 (13.1) | |

| Asian | 52 (5.2) | 22 (3.8) | |

| Other | 9 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) | |

| Total reported | 1007 (100) | 578 (100) | |

| Not reported | 124 | 60 |

Note: Age is measured in average years, sex and race/ethnicity is measured in total count.

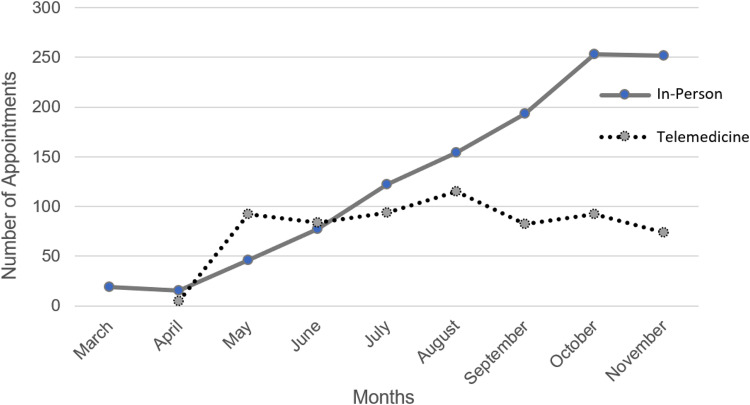

Figure 1 illustrates the changes in the number of patients seen for the two visit types during the study period. Differences between in-person and telemedicine modalities are summarized in Table 2. Diagnostic orders were either increased or equivalent in patients seen in-person compared to telemedicine: imaging [mean + SD], (0.52 ± 0.85 vs. 0.36 ± 0.65 studies/patient, p < 0.001); laboratory tests ordered, (4.87 ± 5.32 vs. 4.05 ± 4.90/patient, p = 0.001); diagnostic procedures performed (0.13 ± 0.33 vs. 0.12 ± 0.33/patient, p = 0.718); and referrals made (0.7 ± 1.07 vs. 0.54 ± 0.84/patient, p < 0.001). Treatments were also increased in the form of medications being prescribed (2.24 ± 2.26 vs. 1.67 ± 2.02, prescriptions/patient, p < 0.001). The majority of outcome measures demonstrated no difference in the number of emergency room visits (0.04 ± 0.25 vs. 0.02 ± 0.14/patient in 3 months, p = 0.61), follow-up visits (1.21 ± 0.44 vs. 1.21 ± 0.46, p = 0.92), or telephone encounters (1.21 ± 1.83 vs. 1.12 ± 1.83, p = 0.35). However, the number of electronic communications were decreased in in-person visits as opposed to telemedicine visits (3.97 ± 7.43 vs. 5.12 ± 8.40, p = 0.003). Subgroup analysis found no statistical difference between the number of follow-up appointments demonstrating that 21.2% of patients in the in-person visit group followed up within 3 months of their initial GI visit (12.7% seen as in-person visit and 8.5% seen as telemedicine visit) while in the telemedicine group 21% of patients followed up within 3 months of their initial GI visit (10.5% seen as in-person visit, 10.5% seen as telemedicine visit) (Table 3). Finally, a list of all diagnosis of patients seen subsequent to their GI visit in the emergency room and whether or not those patients were admitted to the hospital were included in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Number of appointments by modality over time.

Table 2.

Clinical measures between in-person and telemedicine visits.

| Measures | In-person mean (SD) | Telemedicine mean (SD) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | |||

| Imaging orders | 0.521 (0.852) | 0.364 (0.646) | <0.001* |

| Lab orders | 4.867 (5.317) | 4.049 (4.901) | 0.001* |

| Procedures | 0.128 (0.334) | 0.122 (0.328) | 0.718 |

| Referrals | 0.700 (1.070) | 0.536 (0.841) | <0.001* |

| Treatment | |||

| Medication orders | 2.236 (2.255) | 1.668 (2.024) | <0.001* |

| Outcome | |||

| Emergency room visits | 0.037 (0.246) | 0.017 (0.142) | 0.61 |

| Follow-up visits | 1.208 (0.443) | 1.210 (0.495) | 0.922 |

| Electronic communications | 3.967 (7.428) | 5.119 (8.393) | 0.003* |

| Telephone encounters | 1.208 (1.829) | 1.124 (1.827) | 0.354 |

*Indicates statistical significance, α <.05.

Table 3.

Percentage of follow-ups by visit type after initial in-person or telemedicine visit.

| Visit type | Total number of visits | Percent of total follow-up visits 3 months after initial visit | Percent in-person | Percent telemedicine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-person | 1131 | 21.2* | 12.7 | 8.5 |

| Telemedicine | 638 | 21* | 10.5 | 10.5 |

*p-value = 0.47.

Table 4.

List of diagnosis for patients seen in ER for abdominal pain within 3 months of clinic visit.

| Reasons | In-person | Video | Admission |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute heart failure | 1 | 0 | Y |

| Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome | 1 | 0 | N |

| Choledochal cyst | 1 | 0 | N |

| Choledocholithiasis | 1 | 0 | N |

| Constipation | 2 | 2 | N |

| Gastritis | 2 | 3 | N |

| General abdominal pain | 8 | 2 | N |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1 | 0 | Y |

| Migraine | 1 | 0 | N |

| Ovarian torsion | 0 | 1 | N |

| Pancreatitis | 1 | 0 | N |

| Renal carcinoma | 0 | 1 | Y |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | 0 | N |

| Viral gastroenteritis | 3 | 0 | N |

| Total ER diagnosisa | 23 | 9 | n/a |

| Total admissions | 2 | 1 | 3 |

For patients with multiple ER visits, only the last ER visit was used for diagnosis.

The data demonstrates that in-person visits utilize more resources (diagnostic and treatments) than telemedicine visits while at the same time having equivalent outcome measures. There was no significant difference between race/ethnicity in choosing in-person or telemedicine visits nor was there a difference in the mode or frequency of follow-up at 3 months. Emergency room visit diagnosis was also seen to be similar between the two visit modalities.

Discussion

In this study, the differences between diagnostic, treatment, and outcome measurements were compared between patients presenting (either in-person or via telemedicine) to pediatric GI clinics for a chief complaint of abdominal pain. This study did demonstrate that in-person visits utilize more resources (diagnostic tests and treatments) than those seen in the telemedicine group. The in-person setting may be associated with increased patient demands, greater ease of ordering, and increased provision of services (additional staffing) which likely helps to facilitate these increased resource utilizations. But as noted by Wallis et al., many of the diagnostic tests ordered for abdominal pain do not lead to a diagnosis which may point to less testing being indicated. There was no difference in procedures performed between the two groups. This is likely due to the infrequency of procedures being performed but may, along with outcome measures, demonstrate a similarity in symptom/disease severity between the two groups.

When comparing outcome measures, the study did not demonstrate a difference in emergency room visits, follow-up appointments, or telephone encounters performed, demonstrating a congruence in the severity of patient symptoms between the two groups. Particularly, emergency room visits (Table 4) share a similarity in the final diagnosis in these patients. Electronic communications were decreased in the in-person group which could demonstrate a discrepancy in symptom severity. However, this difference is more likely related to a selection bias (in-person patients are not required to sign up for electronic communications while telemedicine patients must sign up for electronic communications in order to complete a telemedicine visit) which may lead to more messages being sent/received. Alternatively, in-person visits may be more complete or felt to be more complete by patients and their families leading to the diminished use of electronic communication after the visit.

There were important limitations to this study. Our study did lack a direct outcome measure to assess abdominal pain severity between the two groups. The study focused on short-term outcomes (3 months of follow-up) and a future study is needed to examine longer-term outcomes. A prospective study comparing symptom scores, days missed from school, and quality of life measurements would be beneficial in assessing these differences. However, measures such as emergency room visits, follow-up visits, telephone encounters, and procedures would likely be increased in patients with a more severe presentation and we did not see any evidence of this in our analysis. The study did not capture patients who may have been seen at other care centers outside of the Texas Children's Hospital or contacted other providers (i.e. primary pediatric offices) with abdominal pain complaints. We believe that given our sample sizes, these limitations should be equally distributed between the two groups. The lack of a physical exam in the telemedicine group and differences in assessments (based upon visit modality) could artificially decrease the suspicion of providers that would have been caught during an in-person visit. But again, we would expect to see more follow-up visits, procedures performed, or emergency room visits if this were the case. Lastly, there is a possibility that distance from the hospital played a role in visit type selection but this was not examined in our study.

Despite these limitations, our study does suggest telemedicine is a valid visit modality in the treatment of pediatric abdominal pain. This complaint is one that has a low prevalence of severe specific underlying pathologic processes and thus potentially favors telemedicine. Telemedicine appears to utilize less resources than in-person visits and may have equivalent outcomes. It is also, potentially, much more convenient for patients and their families. Relative to more traditional in-person care, the study of telemedicine in the assessment and management of not only pediatric abdominal pain but a wide variety of both pediatric and adult visit reasons warrants future prospective analyses.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Amir Jazayeri https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1684-1501

References

- 1.Medicine BoHCSIo. The Evolution of Telehealth: Where Have We Been and Where Are We Going? - The Role of Telehealth in an Evolving Health Care Environment Volume 2021. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US), 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AC. Telepaediatrics. J Telemed Telecare 2007; 13: 163–166. PMID: 17565770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Portnoy JM, Waller M, De Lurgio S, et al. Telemedicine is as effective as in-person visits for patients with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2016; 117: 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McConnochie KM, Conners GP, Brayer AF, et al. Differences in diagnosis and treatment using telemedicine versus in-person evaluation of acute illness. Ambul Pediatr 2006; 6: 187–195. discussion 196–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snoswell CL, Chelberg G, De Guzman KR, et al. The clinical effectiveness of telehealth: A systematic review of meta-analyses from 2010 to 2019. J Telemed Telecare 2021. 10.1177/1357633X211022907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raphael BP, Schumann C, Garrity-Gentille S, et al. Virtual telemedicine visits in pediatric home parenteral nutrition patients: A quality improvement initiative. Telemed J E Health 2019; 25: 60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone JM, Gibbons TE. Telemedicine in pediatric gastroenterology: An overview of utility. Telemed J E Health 2018; 24: 577–581. Epub 2017 Dec 22. PMID: 29271722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JA, Di Tosto G, McAlearney FA, et al. Physician perspectives about telemedicine: Considering the usability of telemedicine in response to coronavirus disease 2019. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2021; 73: 42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Love M, Hunter AK, Lam G, et al. Patient satisfaction and perceived quality of care with telemedicine in a pediatric gastroenterology clinic. Pediatr Rep 2022; 14: 181–189. PMID: 35466204; PMCID: PMC9036210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallis EM, Fiks AG. Nonspecific abdominal pain in pediatric primary care: Evaluation and outcomes. Acad Pediatr 2015; 15: 333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]