Abstract

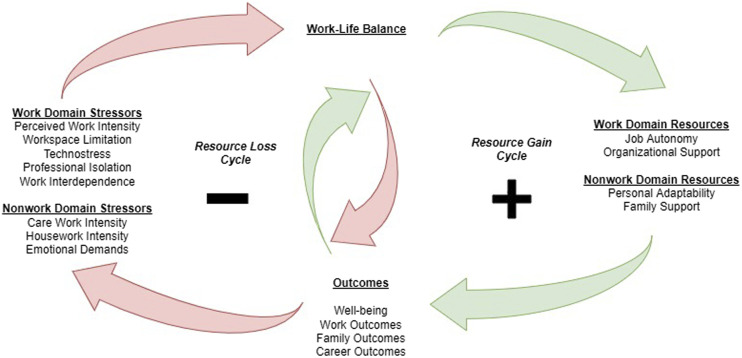

We present a systematic review of 48 studies conducted between March 2020 and March 2022 that examined work-life balance (WLB) among those who worked from home. We propose a conceptual framework that organizes the antecedents and outcomes of WLB based on resource loss and gain. Resource loss occurred when employees faced stressors such as perceived work intensity, workspace limitations, technostress, professional isolation, work interdependence, housework intensity, care work intensity, and emotional demands. Resource gain was likely when employees were supported by resources such as work supervisors and family members, received job autonomy, and were personally adaptable. Our findings have resonance for remote work contexts beyond the pandemic by seeking patterns across the literature that examined WLB while working from home. We contextualize antecedents and outcomes of WLB and suggest stressors and resources that impact WLB are dynamically related. Our review informs HRD practitioners as they manage the post-pandemic remote work.

Keywords: work-life balance, work from home, remote work, review, pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (hereafter, the pandemic) and its stay-home orders introduced an unprecedented context and a unique opportunity to examine work-life balance (WLB) while working from home, away from primary offices, and communicating virtually via electronic media. A massive number of workers worldwide had to work from home with little preparation and for an unknown length of time (McKinsey Global Institute, 2021). Employees working from home lost the boundaries between work and home while worrying about their health and that of their families (Fogarty et al., 2020). These changes in work and family circumstances impacted the WLB experiences of employees in various ways that many researchers found critical to study. In this review, we bring together the empirical research conducted so far on WLB among those who worked from home during the pandemic. The review of this literature is particularly timely because the pandemic has accelerated the rise of work from home, turning it from request to requirement. Seventy-nine percent of respondents to a Deloitte survey reported that at least 75% of their workforce worked from home during the pandemic, while 69% said their company managed and supported employees well or excellently (Deloitte, 2021). As organizations search to define a “next normal” and continue to make decisions about work from home and hybrid work options, it is critical that they understand what employees’ WLB was like while they worked from home during the pandemic. Specifically, knowing the antecedents and outcomes of WLB can inform employers’ decisions about how to facilitate work from home for the next generation of employees.

We argue that the pandemic showcases an extreme example of maintaining WLB while working from home, a phenomenon that extends beyond the pandemic (e.g., ILO, 2021). Employees’ post-pandemic interest in working from home and the rapid increase in the number of remote workers suggest there is a need to continuously consider what impacts the WLB of those working from home (e.g., McKinsey Global Institute, 2021). The interruptions brought about by the pandemic presented unprecedented opportunities to HRD scholars and practitioners to re-examine, re-design, and re-imagine the organizational, developmental, and leadership solutions and voice remote employees’ concerns (Arora & Suri, 2020; Bierema, 2020; Davies, 2021; Hite & McDonald, 2020; Li et al., 2020; Yawson, 2020).

While the extant literature on WLB acknowledges the consequences of work and nonwork demands for WLB (e.g., Allen, 2012; French & Johnson, 2016) and the work and nonwork support in leveraging WLB (Masterson et al., 2021), further investigation is needed to capture the implications of work from home context for WLB. Despite longstanding calls to contextualize management research in general (Bamberger, 2008), and WLB research in particular (Powell et al., 2019), the few literature reviews that have acknowledged the impact of context on WLB have tended to focus on country context (Ollier-Malaterre et al., 2013; Shockley et al., 2017), rather than on work from home circumstances. In an earlier publication, our research team took initial steps toward understanding WLB within the context of work from home (Shirmohammadi et al., 2022). Adopting the person-environment fit theory (Hesketh & Gardner, 1993) and a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) of both previous WLB literature reviews and meta-analyses (e.g., Byron, 2005) and the COVID-induced literature, we compared the desirable aspects of work from home and its undesirable aspects that surfaced during the pandemic (Shirmohammadi et al., 2022). This earlier work established the need for a detailed examination of antecedents and outcomes of WLB while working from home and motivated our current review paper.

The pre-pandemic research has been inconclusive regarding the WLB of employees working from home, since studies have shown that flexibility of work from home both increases and decreases WLB (e.g., Allen & Shockley, 2009; Spreitzer et al., 2017). It is necessary to examine the research that followed the pandemic to understand the dynamics of WLB while working from home. The existing reviews of the research conducted during the pandemic within the extant human resources literature have focused on gender inequalities and the psychological well-being of healthcare workers, while paying only limited attention to WLB. This review complements previous reviews and the extant WLB research by focusing on WLB while working from home during the pandemic and contextualizing its antecedents and outcomes.

In this study, we have conducted a systematic literature review to identify, organize, and synthesize peer-reviewed empirical studies that reported antecedents and outcomes of WLB while working from home during the pandemic. We drew on conservation of resources theory (COR) (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018) to argue that while working from home probably made access to certain resources such as schedule flexibility and time for family members easier (i.e., resource gain), it also diminished employees’ ability to use certain resources, such as space and time for work causing stress (i.e., resource loss). We acknowledge that there are several concepts in the extant literature referring to the interface between work and life domains, each with its own strengths and limitations. In this paper, we used the term WLB as an overarching term that encompasses the different ways personal and professional life interact and impact one another. We define it as the experience of satisfaction in work and nonwork domains (Kirchmeyer, 2000). This review extends extant literature on WLB by presenting an integrative model informed by COR theory and by explaining how WLB while working from home can be impacted by both resource loss and resource gain. Also, we identify stressors and resources associated with WLB while working from home during the pandemic, and then we provide practical recommendations for employers, management, and human resource development (HRD) practitioners concerned with enhancing employees’ WLB.

Theoretical Background and Review Framework

Work-Life Balance

Several decades have passed since the intersection of work, and life roles have become recognized as a key area of study within multiple disciplines (e.g., management and organizational studies, industrial relations, psychology, sociology, social work, family studies), resulting in a large body of empirical evidence (e.g., Allen, 2012; French & Johnson, 2016). As this area of research has matured over time, various terms have emerged to describe the interface between work and life roles (see reviews of the literature such as Beigi et al., 2019). Research consistently demonstrates that the management of work and family roles can be a challenge. However, combining work and life roles also provides benefits and opportunities for enrichment. In this review, we use the term WLB as an umbrella term to include all research involving the juxtaposition of multiple conceptualizations of the work-life interface.

A central focus of WLB scholarship has been the exploration of antecedents and outcomes. Reviews of past research have synthesized the empirical research and suggested models that show work and life factors variables that predict balance and its outcomes (e.g., Allen, 2012; Brough & Kalliath, 2009; Greenhaus & Allen, 2011; Jain & Nair, 2013; Kalliath & Brough, 2008; Sirgy & Lee, 2018). Although these reviews have categorized predictors of balance in slightly different ways, they all include work and nonwork factors. For example, long work hours has been associated with less perceived balance and quality time with children has been positively related to perceived balance (e.g., Allen, 2012). As far as WLB outcomes, a diverse range of outcomes have been associated with WLB, including work (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational commitment) and nonwork (e.g., family satisfaction and life satisfaction) outcomes (e.g., Sirgy & Lee, 2018). Some have criticized the WLB scholarship because of a narrow focus on nuclear family roles (Allen, 2012; Beigi et al., 2019) or a dominant quantitative methodology approach (Beigi & Shirmohammadi, 2017), thus constraining research and theory. Although such debates are important dialogue for the field, they are outside of the scope of this review.

WLB While Working from Home

Work from home involves individual workers performing tasks from home, away from their primary offices, using electronic media to interact with others inside and outside the organization (Spreitzer et al., 2017). Since Work from home places work and family domains in the same physical space, many researchers have been interested in examining WLB among employees working from home. Existing research that has examined the WLB of employees working from home reveals two themes: (1) work from home positively influences WLB through increased flexibility, and (2) work from home negatively impacts WLB through blurred work-family boundaries and increased managerial control.

First, researchers have argued that Work from home inherently provides flexibility and control over when and where to work, which could be considered a valuable resource to meet family responsibilities. Studies have provided evidence that perceived control could positively relate to employee WLB (e.g., Hill et al., 2010). Also, control over work time, with flexibility in allocating time for different work and nonwork activities, has been shown to have beneficial effects for employees; this aspect of control is not an inherent component of work from home but sometimes accompanies it (e.g., Valcour, 2007). Studies on work from home that concern women’s experiences (Smithson & Stokoe, 2005) suggest that flexible work scheduling allows mothers to maintain their total full workload after childbirth (Chung & van der Horst, 2018); however, due to pre-existing views on gender roles and gender normative views towards men’s and women’s roles and responsibilities (Blair-Loy, 2001), flexible working hours can potentially reinforce traditional gender roles in workplaces and households (Smithson & Stokoe, 2005).

Second, scholars have assumed that Work from home can weaken the boundary between work and home domains, which may require boundary management to deal with family interruptions (Makarius & Larson, 2017). Employees who work from home part-time were found to make more work-to-family transitions (i.e., interruptions of work activities to deal with family demands during work hours) on work from home days, which was related to lower work-to-family conflict but higher family-to-work conflict on days they worked from home (Delanoeije et al., 2019). Other researchers have argued that while working away from traditional workplaces can give employees a greater sense of independence (Sewell & Taskin, 2015), it simultaneously generates new surveillance mechanisms (Valsecchi, 2006). Popular representations of flexible work often depict it as “technologically feasible, flexible and autonomous, desirable and perhaps even inevitable, family- and community friendly, and more” (Bryant, 2000: p. 22). However, the common images of autonomy give unrealistic pictures of the control exercised over employees working from home (Valsecchi, 2006). While the above body of literature has portrayed the advantages and disadvantages of work from home, it rarely taps into mechanisms beyond flexibility, control, and work-home boundaries. We address this gap by drawing on COR theory and outlining resource loss and gain dynamics.

COR Theory

We borrow from the COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989), which provides ways to bring together different strands of research regarding work from home and WLB. It offers a lens to explore how combinations of factors can define the WLB experiences of employees working from home. COR theory puts the concepts of stressors and resources at the center of analysis, which in combination, offer a useful lens to integrate the existing research. Resources have been defined as structural or psychological assets of the individual that may be used to facilitate performance, reduce demands, or generate additional resources (Voydanoff, 2004). The term stressor is used to refer to experiences an individual perceives as taxing or exceeding resources (Taylor & Stanton, 2007). Resource loss leads to stressors and occurs when personal resources are threatened with loss or are lost. In contrast, resource gain occurs when an employee has the required resources to address work and life stressors or can build additional personal resources to do so (Hobfoll, 2011). COR theory also explains that individuals who lose personal resources due to broader life contexts are more vulnerable to further resource loss (Hobfoll, 1989).

The pre-pandemic research addressing work from home and the changes it brings to employees' work and nonwork domains of life points to emergences of resource loss (i.e., stressors) and gain as well. First, some evidence has outlined possible resource losses from working at home, such as the decreased ability of employees to receive help by physically and informally turning to a supervisor or colleagues nearby, or the loss of opportunities to receive feedback from supervisors (Kossek et al., 2006). Studies have shown that employees working from home associated such loss of resources with feelings of social isolation, career stagnation, and work-family conflict (Baruch & Nicholson, 1997). Also, due to less commuting, employees working from home may lose fewer personal resources, such as time, energy, and attention, than those working in an office (Hartig et al., 2007; Wang & Ozbilen, 2020). On days spent working from home, employees are less likely to experience the burden of social interaction at work, which involves the need to invest personal resources, such as time, attention, and effort, in creating and maintaining social relationships at work (Biron & van Veldhoven, 2016). Work from home inherently provides valuable resources, such as relative control and flexibility over where work gets done, which has been found to be positively related to employee perceptions of WLB (e.g., Hill et al., 2010). Control over work time and flexibility in the allocation of time for different work and nonwork activities have been shown to have beneficial effects on employees (Valcour, 2007). We take cues from these studies and draw on COR theory and resource loss and gain dynamics to identify antecedents (i.e., stressors and resources) and outcomes associated with WLB while working from home.

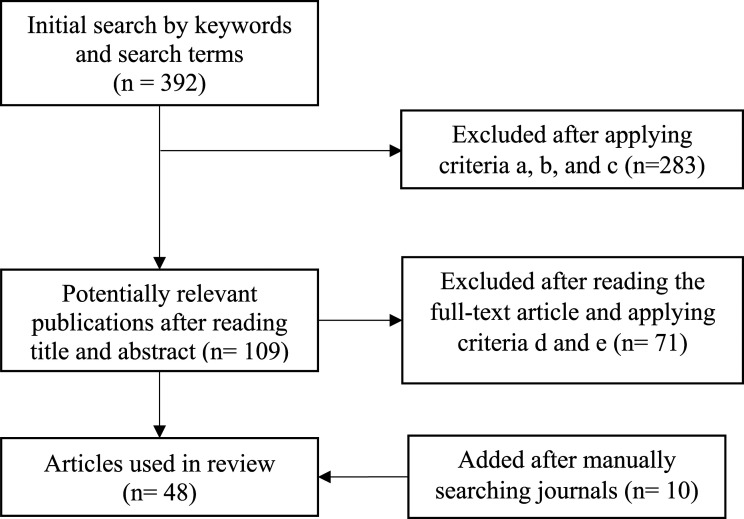

Methods

Our review builds on a dataset collected for an earlier publication by Shirmohammadi et al. (2022) that analyzed desirable and undesirable aspects of work from home (for details see Appendix A). We adopted a systematic review approach to identify and retrieve relevant literature that examined WLB and work from home during the pandemic. This approach to reviewing a body of literature synthesizes research findings in a transparent manner, thus enhancing extant knowledge and informing subsequent research and practice (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009). For this paper, we followed the steps used by Shirmohammadi et al. (2022) to retrieve an updated dataset. Our database search involved searching titles and abstracts of publications indexed in the Social Science Index (Web of Science), using Boolean operators and keywords: “work-from-home*,” “telework*,” “telecommut*,” “covid*,” “corona*,” and “pandemic,” to retrieve as many relevant records as possible. The search retrieved 392 records, which we exported to Refworks for further screening. To retrieve the most relevant studies, we focused on journals labeled as Management, Business, Applied Psychology, Economics, Sociology, Family Studies, and Gender Studies. We read the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the retrieved publications and screened them according to the following questions: (a) Does the article report an empirical study (not conceptual or descriptive)? (b) Does the article focus on the work-life interface while working from home? (c) Is the article related to the pandemic? (d) Was the respective data collected during the pandemic? and (e) Does the study describe antecedents or outcomes of WLB while working from home? Articles that did not meet one or more of the inclusion criteria were not short-listed for the review (See Figure 1). Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies were included in the review. We also manually searched 63 journals, listed as 3* and 4* by the CABS Academic Journal Guide 2018 under the categories of Organization Studies, Human Resource Management, Organizational Behavior, and Organization Psychology, to make sure we had captured all relevant articles. In this step, we identified 10 articles and included them in our review. As shown in Appendix B, our completed dataset included 48 articles published from March 2020–2022 (cut-off: 25 March 2022).

Figure 1.

Article search and selection.

Note. (a) Does the article report an empirical study (not conceptual or descriptive)? (b) Does the article focus on the work-life interface while working from home? (c) Is the article related to the pandemic? (d) Was the respective data collected during the pandemic? and (e) Does the study describe antecedents or outcomes of WLB while working from home?

In addition to coding for general information, including publication year, authors, and journal, the papers were also coded into a literature review matrix (Garrard, 2017) according to the following criteria: research purpose and/or questions, hypotheses, research methodology, theoretical foundation, context, and findings. To provide an overview of the reviewed studies, we summarized corresponding columns to report the frequency of codes (e.g., methodology and context). We then took the following steps to integrate the findings of the reviewed articles. We divided our sample into quantitative and qualitative studies (we included mixed methods studies in both groups). For the quantitative studies, we recorded the hypotheses that examined the work from home, WLB, and its antecedents and outcomes, and reported a significant relationship. For qualitative studies, we treated the findings section as qualitative data and coded it for factors related to WLB while working from home. We consulted previous WLB literature reviews (e.g., Allen, 2012; Brough & Kalliath, 2009; Greenhaus & Allen, 2011; Jain & Nair, 2013; Kalliath & Brough, 2008; Sirgy & Lee, 2018) to determine which variables or factors are considered stressors, resources, or outcomes according to the extant WLB scholarship. In the case of the quantitative studies we reviewed, often the hypotheses determined which variables were considered stressors, resources, or outcomes. In qualitative studies we examined the research questions or purpose, and direct quotations from participants to determine stressors, resources, or outcomes. In the second step, we grouped together categories indicating similar stressors, resources and outcomes of the work from home and work-life interface. This step led to 37 categories, which we further grouped into 13 major categories by referring to COR theory and WLB literature (see Appendix C). Drawing on COR theory, we concluded that resource loss and gain could be used as a lens through which to explain the stressors, resources, and outcomes of WLB while working from home during the pandemic. Resource loss and gain processes explained the negative and positive relationships among the identified categories. Adopting COR theory as a theoretical framework sets our work apart from Shirmohammadi et al. (2022) which used person-environment fit theory (Hesketh & Gardner, 1993) to highlight the contrast between desirable and undesirable aspects of work from home. COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) in this review enabled the organization of antecedents and outcomes and provided theoretical tools to explain the connections among the identified factors.

It is important to note that a quantitative meta-analysis or qualitative meta-synthesis was not feasible, as the included studies were not sufficiently similar (Grant & Booth, 2009). In addition, specific comparisons (developing vs. developed country) were not possible, owing to the small number of studies in each category. Two of the authors were engaged in all the steps of the systematic review. One author took the lead in analyzing the whole dataset. The other author reviewed the categories and subcategories and raised questions when there was a disagreement. They discussed their interpretations of the respective themes until they settled on a final agreed interpretation.

Findings

Seventy-three percent of the studies adopted a quantitative methodology, 23% were qualitative, and 4% were mixed-methods studies. Studies were conducted in the USA (n = 12), Italy (n = 5), India (n = 3), Canada (n = 3), Switzerland (n = 2), Australia (n = 2), China (n = 2), France (n = 2), the Netherlands (n = 2), Spain (n = 1), Israel (n = 1), the UK (n = 1), Germany (n = 2), Kosovo (n = 1), Lithuania (n = 1), Romania (n = 1), Greece (n = 1), Turkey (n = 1), Iceland (n = 1), Ireland (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1), Ghana (n = 1), Argentina (n = 1), and in more than one country (n =7). Taken together, our review reflects studies conducted in 18 high-income and developed countries such as USA and Singapore (33 studies), five upper-middle-income and developing countries such as China and Turkey (6 studies) and 2 low-income countries including India and Ghana (4 studies). One study did not specify the country where the data was collected. The majority of the quantitative studies depended on single-source or single-time data, and the majority of the qualitative studies collected interview data from a single group. Of the 26 studies that reported industries and occupations of participants, 26 included multiple industries (e.g., education, higher education, finance, information technology, media, public service, legal service) and occupations (e.g., accountants, engineers, scientists, managers, administrative staff, salespeople, designers, counsellors, and civil servants) and 3 involved academics. Forty-six percent of the reviewed studies were informed by a theory, which we have listed in Appendix D.

As we summarized and synthesized the findings of the studies, we categorized the antecedents of WLB while working from home as stressors (i.e., experiences an individual perceives as taxing or exceeding resources) and resources (i.e., valuable assets that could be used to meet demands and reduce stressors). We organized the outcomes of WLB as well-being, work, career, and family outcomes (See Appendix C).

When presenting each category, we report what the quantitative findings in that category tell us about its significant association with WLB in the context of work from home during the pandemic, and we supplement our description with the qualitative findings for the same category. In the following sections, we discuss the connections between stressors and resources in work and nonwork domains as antecedents of WLB, as well as the connections between the WLB and various outcome variables, and we present our overarching conceptual framework (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

An integrative model of the antecedents and outcomes of WLB while working from home during the pandemic.

In the following sections, we present the elements of Figure 1 that have integrated the findings of the 48 studies we reviewed. Adopting the COR theory lens allowed us to explain the dynamics of WLB while working from home as resource loss and resource gain and provide a well-rounded account of how individuals balanced their work and nonwork, and their subsequent outcomes, while they were expected to work at home. We integrate the findings of qualitative and quantitative studies that we believe are complementary. The italicized phrases represent the verbiage we have borrowed from the studies and correspond with the main topics outlined in Appendix C.

Stressors and WLB while Working from Home

Our review revealed five stressors in the work domain (i.e., perceived work intensity, workspace limitation, technostress, work interdependence, and professional isolation) and three stressors in the nonwork domain (i.e., housework intensity, care work intensity, and emotional demands). According to COR theory, work (or nonwork) stressors result from loss of personal resources such as time and energy. Stressors explained in more detail below reflect changes in work or nonwork demands that were related to diminished WLB (a lack of satisfaction with work and life) while working from home during the pandemic for participants in the reviewed studies.

Work Domain Stressors

Perceived Work Intensity

Eleven studies identified intensified work as a common experience, which made attaining WLB while working from home difficult (Del Boca et al., 2020; Molino et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021). Work intensity was referred to as experiences of excessive workload and increased work hours (Burke et al., 2010; Granter et al., 2019). A participant in Wang et al.’s (2021) mixed methods study elaborated on the effects of work intensity while she worked from home during the pandemic as, “I don’t think remote working can give me more personal time; instead, I feel that remote work increases my working time” (p. 27). Intensified work was also manifested in working a double shift and working late at night for those whose work productivity expectations remained the same as before the pandemic (Burk et al., 2020; Craig, 2020; Hertz et al., 2020). This was especially prevalent among academics who were mothers with young children (Burk et al., 2020; Minello et al., 2021; Parlak et al., 2021). A female academic in Parlak et al.’s (2021) study shared about her additional work late at night, “[Work] starting from the nights because my son sleeps at 10 o’clock. After he sleeps, I sit in front of my laptop for two to 3 hours until 1 a.m.” (p. 8). Work intensity was also reflected in constant availability and regular monitoring, which drained resources of participants in the reviewed studies, created stress, and decreased their ability to meet family demands (Wang et al., 2021).

Workspace Limitation

Seven studies referenced workspace limitations at home—scarcity of space, competition for space, and access to an office at home—as main challenges for those working from home during the pandemic (Ayuso et al., 2020; Hertz et al., 2020; Karl et al., 2021; Risi et al., 2021). A participant in Risi et al.’s (2021) study shared, “The real issue is the space because I don’t have a room with an additional spot […] so, I have to work in the living room, with my stack of documents, it’s a mess” (p. S471). A participant in Hertz et al.’s (2020) study had to invent a dedicated space to limit her interactions with her child: “I hide in the RV1 in the yard and pretend I leave to go to work. My son would not leave me to work if he knew I was still there” (p. 21). Other studies noted that those who had decent work space appeared to adjust to the work from home arrangement (Carillo et al., 2021) and to balance work and family responsibilities (Allen et al., 2021). One study in this category suggested that more men had access to an office at home than women (Craig, 2020). For example, mothers in Craig’s (2020) study voiced the frustration of being the main person who must share space with children, “I work downstairs in our living area where I supervise our kid, my husband works upstairs with no supervision duties” (p. 688).

Technostress

While information and communication technology (ICT) made working from home possible, according to nine studies, ICT use was intensified for those who worked from home during the pandemic. Extensive ICT use induced “technostress” (Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008, 417–418) through experiences of techno-complexity, techno-invasion, techno-overload, techno-incompatibility, inadequate tools, and limited access to stable internet connections. Techno-complexity made workers feel inadequate with their ICT skills (Tarafdar et al., 2007) and forced them to deal with stress (Carillo et al., 2021; Molino et al., 2020). Those workers who felt proficient in using ICT for work reported a smooth transition and adjustment to work from home during the pandemic (Carillo et al., 2021). Also, studies highlighted that workers experienced techno-invasion when they perceived ICT to invade their personal lives, techno-overload while they felt pressured to work faster and longer, and techno-incompatibility as they found ICT not fitting their work needs (Tarafdar et al., 2007). Techno-invasion, overload, and incompatibility functioned as stressors that drained resources available to employees working from home in their nonwork domain, and contributed to low WLB (Molino et al., 2020; Vaziri et al., 2020). Inadequate tools and limited access to stable internet connections made working from home challenging (Ipsen et al., 2021; Risi et al., 2021). When ICT was perceived as inefficient for work-related communication, they seemed to impose a time cost on employees who worked from home (Wang et al., 2021). A participant in Risi et al.’s (2021) study voiced frustration regarding their internet connection as “I always have to talk out loud … it’s chaos, so my brother asked me to move somewhere else, but for me it’s not easy to move! If I come up the [internet] signal is way worse” (p. S471).

Professional Isolation

Five studies identified a concern about professional isolation among employees working from home during the pandemic due to the reduction in informal social interactions with colleagues and loss of informal feedback from supervisors (Carillo et al., 2021; Ipsen et al., 2021; Toscano & Zappalà, 2020; Wang et al., 2021). Professional isolation made it difficult to adjust to work from home (Carillo et al., 2021) and led to decreased work from home productivity and satisfaction (Toscano & Zappalà, 2020). As participants in Wang et al.’s (2021) study indicated, lack of intimacy and closeness in virtual interactions accounted for their feelings of loneliness.

Work Interdependence

According to two studies, employees whose work was highly interdependent on others had difficulty adjusting to work from home during the pandemic (Carillo et al., 2021; Chong et al., 2020). Work interdependence could be defined as the extent to which employees had to rely on and interact with co-workers to coordinate efforts and to share materials, information, or expertise in achieving common goals (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006; Van Der Vegt et al., 2001).

Nonwork Domain Stressors

Care Work Intensity

Nineteen studies referenced intensified care work in the forms of active care of young children, supervisory care of school-aged children, remote learning demands, and elderly and sick or disabled family member care. When children were at home all day during the lockdowns or when they were out of school or daycare, childcare time demands increased extensively (Goldberg et al., 2021). Parents were burdened by active care (i.e., care requiring the parents to interact directly with the children, including bathing, feeding, dressing, teaching and playing and supervisory) and supervisory care (i.e., care requiring the parents to be responsible and “on call” should active care be needed) (Craig & Churchill, 2021). Intensive childcare demands restricted working parents’ attention to their paid work, as a participant in one reviewed study claimed, “we cannot remain focused on a task or a meeting due to the incessant demands of our children” (Carillo et al., 2021: p. 79). Del Boca et al. (2020) found that children younger than 5 years old required intense active care, while Goldberg et al. (2021) found that primary school children demanded homework supervision. An academic mother of three young children, in Minello et al.’s (2021) study shared a similar sentiment, “I can’t do live classes because my kids always find me, it doesn’t matter where I go and if the door is locked they’ll bang it down” (p. S90). Accordingly, intense care work for mothers with children under five led to low levels of WLB (Del Boca et al., 2020). Fathers participated in childcare proportionally more than in housework (Craig, 2020; Craig & Churchill, 2021).

During the pandemic, school closures and transition to remote learning pushed parents to assume a teacher’s role for their children while working from home (Clark et al., 2020; Del Boca et al., 2020; Hertz et al., 2020). Parents had to devote a significant amount of time to homeschooling their children. A mother in Risi et al.’s (2021) study explained how homeschooling during lockdown resulted in extra work for her, “He is in second grade and now does 3 online lessons, of 2 hours each, per week. He’s a child, if you don’t stay with him, he’s not going to stay on the computer, or he gets easily distracted … And then there is homework … now it must be done every day” (p. S472).

Three studies examined the distribution of childcare demands among couples, and found that while fathers participated in childcare, mothers still dedicated more time than fathers to caretaking responsibilities (Ayuso et al., 2020; Hennekam & Shymko, 2020; Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, 2021). Three studies indicated that remote learning was more equally shared within couples than housework activities (Chung et al., 2021; Del Boca et al., 2020; Shockley et al., 2021). In addition to childcare, the reviewed studies highlighted that the care demands of the elderly, sick and/or disabled family members added to the burden of unpaid care work at home (Craig & Churchill, 2021), which made working from home difficult. In some country contexts, the expectation to take care of the husband’s needs was an additional layer of care responsibility that women had to manage (Parlak et al., 2021).

Housework Intensity

Thirteen studies highlighted that the lockdowns, and staying home led to an increased amount of housework, including cleaning, cooking, and laundry (Craig & Churchill, 2021; Goldberg et al., 2021; Risi et al., 2021). Those who normally received help with housework were unable to do so during the pandemic, which also increased demands on them. Accordingly, managing household chores was reported as an increase in unpaid work at home (Craig & Churchill, 2018; Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, 2021). A mother in Hjálmsdóttir and Bjarnadóttir’s (2021) study said, “I have turned into a foreman here at home. I am trying to get clearer oversight over what has to be done and activate my husband to prevent everything from becoming a mess ….” (p. 277). However, most of the additional housework during the pandemic was still handled by women, according to the studies in this category (Ayuso et al., 2020; Del Boca et al., 2020; Parlak et al., 2021). As one of the participants in Craig’s (2020) study stated, “I suddenly find I’m living in decades gone by in terms of house and family care load, but also expected to continue to work” (p. 688).

Studies that examined the distribution of housework among couples reported that, while during the pandemic men spent more time on housework than before, women were still the primary bearer of the additional housework during lockdowns (Chung et al., 2021; Craig & Churchill, 2021). While both fathers and mothers were dissatisfied with how the housework was shared during the pandemic, the dissatisfaction was much higher among women (Craig & Churchill, 2021). In many cases, men played supporting roles, such as grocery shopping, while women were responsible for demanding roles, such as routine house chores, including cooking and cleaning (Parlak et al., 2021). Highlighting the fact that women were more easily interrupted by household responsibilities while working from home, a woman participant in one reviewed study reported that “It is obvious that he takes his space when he needs to attend to ‘his’ things, and I run, and I sprint from my work much more than he does” (Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, 2021, p. 276).

Emotional Demands

Emotional demands require one to sustain emotional effort while interacting with others (Vegchel et al., 2004), including the emotional stress of care for others at home (Cottingham et al., 2020). Fourteen studies suggested that working from home during the pandemic was charged with intensified emotional demands related to uncertainties and health concerns for oneself or family members (Ayuso et al., 2020; Goldberg et al., 2021; Toscano & Zappalà, 2020). As one of the participants revealed, “[I have] a lot of anxiety for our loved ones and our lives … during this exceptional period” (Carillo et al., 2021: p. 80). As explicitly mentioned in four studies, health uncertainty pertaining to the pandemic was a constant source of stress (Carillo et al., 2021; Risi et al., 2021; Trougakos et al., 2020).

Concerns related to the effects of confinement on family members’ mood or mental health and the psychological welfare of children (Ayuso et al., 2020; Clark et al., 2020; Goldberg et al., 2021) added to the emotional demands among working parents during this period. A father in Goldberg et al.’s (2021) study revealed, “The stress of the pandemic has really strained our family to the breaking point. Our oldest child has been having a lot of behavioral issues, making the situation even more acute” (p. 17). As mentioned in Clark et al.’s (2020) and Hjálmsdóttir and Bjarnadóttir’s (2021) studies, parents tried to hide their stress and anxiety from family members to keep everyone calm. One of the participants in Hjálmsdóttir and Bjarnadóttir’s (2021) study mentioned “The days are getting really difficult … The younger child is not happy about [the situation] and cries over everything …. The little patience I have is running out, but I try my best not to let her see it” (p. 277). Two of the reviewed studies showed that women were more likely than men to be burdened by emotional demand in handling the anxiety and psychological stress of family members (Hennekam & Shymko, 2020; Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, 2021).

The pandemic confinement led to blurred boundaries between work and nonwork spheres and made employees feel emotionally overwhelmed (Ayuso et al., 2020; Pluut & Wonders, 2020; Risi et al., 2021). A mother in Risi et al.’s (2021) study commented, “home was a sort of shelter … it was a space in which one used to say “I go home and I have a break,” now this break doesn’t exist anymore, because everything, private and professional life, is inside the home” (p. S473). Also, the lack of social interactions and being together all the time in a confined space led to tense relationships and stress (Goldberg et al., 2021; Ipsen et al., 2021). Such relationships density added another layer of emotional demand while working from home (Ayuso et al., 2020; Goldberg et al., 2021; Ipsen et al., 2021; Parlak et al., 2021). Two studies indicated that emotional labour was particularly intense during the early days of the pandemic (Clark et al., 2020; Parlak et al., 2021). One of the participants in Parlak et al.'s (2021) study declared, “I had hard times at first. [I] could not get organized. Meals, on the one hand, and how could we make plans with my daughter? We have not spent such a long time together in the house. Moreover, we were baffled. It was bizarre” (p. 6).

Resources and WLB While Working from Home

Our review of the studies revealed two resources in the work domain (i.e., job autonomy and organizational support) and two resources in the nonwork domain (i.e., family support and personal adaptability). According to the COR theory, gaining resources would give employees the means to meet their work or nonwork demands. The resources suggesting gain are explained in more detail below.

Work Domain Resources

Job Autonomy

Four studies showed that job autonomy—the freedom and flexibility to schedule work and make decisions independently (Hackman & Oldham, 1975)—facilitated the transition to work from home during the pandemic (e.g., Carillo et al., 2021; Chong et al., 2020). Accordingly, the freedom to adapt the schedule while working from home was particularly crucial to juggle work and nonwork responsibilities (Ipsen et al., 2021). The beneficial relationship between job autonomy and WLB was demonstrated in a quotation in Wang et al.’s (2021, p. 27) study: “I can control the rhythms of work and rest. If it is not during the meeting, I can have a short break, around 10 to 30 minutes, and then continue to work. That also means more time to spend time with my family.”

Organizational Support

Three studies showed that task and emotional support provided by organizations were highly valuable in helping employees maintain WLB while working from home during the pandemic (Carillo et al., 2021; Chong et al., 2020; Vaziri et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021). In terms of task support, employees appreciated tangible support such as software and other ICT tools, timely information and relevant work materials, which facilitated the transition to work from home (Carillo et al., 2021; Chong et al., 2020). A study also identified the importance of social support to help employees cope with stress and loneliness, stay focused on tasks, and balance work and life responsibilities while working from home (Wang et al., 2021).

Three studies showed that supervisors and leaders were the gatekeepers of support, and could mitigate the employees’ stress while working from home during the pandemic (Bhumika, 2020; Lamprinou et al., 2021; Vaziri et al., 2020). A participative leader who engaged with subordinates in deciding the work schedule and setting performance targets could help employees cope with stress in the demanding pandemic context and sustain WLB (Bhumika, 2020). Also, compassionate supervisors, who empathized and recognized employees’ concerns, and supervisors who demonstrated a high level of family supportive supervisory behaviour facilitated employees’ WLB (Vaziri et al., 2020). Finally, servant leadership seemed to increase employees’ perceived organizational support and WLB (Lamprinou et al., 2021).

Nonwork Domain Resources

Personal Adaptability

Eight studies found that individual adaptability in different forms was important for WLB while working from home during the pandemic. Wang et al.’s (2021) study showed that having self-discipline to complete tasks efficiently and in a timely manner leveraged WLB. Along the same line, two studies found that individuals who preferred to segment work and family seemed to achieve WLB (Allen et al., 2021; Vaziri et al., 2020). One study suggested that optimism facilitated adjustment to work from home during the pandemic (Biron et al., 2020). Raišienė et al. (2020) found telework skills and digital literacy beneficial, and Pluut and Wonders (2020) found adopting a healthy lifestyle useful to help balance work and personal life while working from home. However, Vaziri et al.’s (2020) study found that people using emotion-based coping strategies were most likely to experience increased work-family conflict and decreased work-family enrichment.

Family Support

Five studies found that the presence of family members functioned as sources of tangible and social support. Those living in multi-adult households could seek out family assistance to cope with work interruptions, share education tasks, and other household tasks (Hertz et al., 2020). In contrast, single mothers who lived in single-adult households, struggled alone with intensive household responsibilities and childcare demands (Clark et al., 2020; Hertz et al., 2020). A single mother living alone with a five-year-old child voiced the challenge she faced when working from home during the lockdown and said “[My daughter] wanders into the background of Zoom meetings a lot. I have to mute myself a lot because she is being loud in the background.” (Hertz et al., 2020: p. 11).

Family members were also important sources of social support that single mothers and single-adult households lacked (e.g., Hertz et al., 2020). Mothers from Hertz et al.’s (2020) study shared, “As a solo mom …, it’s incredibly draining to have a toddler around 24/7 with no chance for a break. It’s relentless” (p. 14). For married workers, the partners served as the main source of support for one other. If a partner continued to work outside of the home, the other partner found it challenging to balance paid work, housework and care work (Del Boca et al., 2020).

Outcomes of WLB while Working from Home

As described in the previous sections, the reviewed studies suggested that stressors and resources were associated with WLB of those working from home during the pandemic. Balance or lack of balance, then, influenced employees’ well-being, career, work, and family outcomes. In the following sections, we present a synthesis of the findings regarding such outcomes.

Well-Being

Well-being refers to a person’s optimal psychological condition or general state needed for effective functioning (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Fifteen studies found evidence of a diminished well-being, such as emotional exhaustion, anxiety, depression, tiredness, negative emotions, and stress among participants who were working from home (e.g., Bhumika, 2020; Chong et al., 2020; Clark et al., 2020; Goldberg et al., 2021; Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, 2021; Pluut & Wonders, 2020). The competing demands from work and nonwork spheres imposed a cognitive burden on working parents as described by a participant in Parlak et al.’s (2021) study “I joined the classes with my daughter sitting on my lap … I was exhausted … I even could not change my clothes for a class once …. It was so hard …. My eyes were on my daughter all the time. It is like splitting your brain” (p. 8). Similarly, a participant in Hertz et al.'s (2020) study expressed a strong sense of malaise to cope with endless interruptions due to domestic responsibilities while working from home, “The quality of engagement with my work suffered due to constant interruptions, general lack of motivation, and feelings of futility” (p. 12).

Two studies showed that feelings of inadequacy resulting from imbalance between work and nonwork roles were common among participants while they worked from home during the pandemic (Minello et al., 2021; Parlak et al., 2021). The following quotation demonstrates such feelings of inadequacy as a worker: “it is more tiring psychologically due to uncompleted tasks, disruption of our daily routine, [and] having to work late at night, and you cannot be productive because you are tired” (Parlak et al., 2021: p. 10). Participants also felt inadequate as a parent as represented in the following quote from Parlak et al.’s (2021) study: “You feel insufficient because you cannot catch up with the things that should be done. You question your motherhood. You say to yourself, Am I not capable of organizing the house?” (p. 12). One other study pointed out, working parents felt overwhelmed with competing and overlapping multiple work and nonwork roles, which also led to feelings of inadequacy (Hennekam & Shymko, 2020). One participant in Hennekam and Shymko’s (2020) study summed up her feeling of inadequacy as “I’m a bad mother, a bad wife, and a bad worker” (p. 796).

Other studies suggested that feelings of guilt and shame were reported among parents who felt they had not performed the parenting role as they wished (Clark et al., 2020; Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, 2021; Parlak et al., 2021). The feeling of guilt also emerged when issues arising from WLB undermined one’s work role, as declared by a participant in Clark et al.’s (2020) study “when you were working. You were feeling guilty because you weren't. You know, helping you know? … I hope nobody’s looking for me … But at the same time, it was tricky because and you know, I suppose you have a good work ethic and you want to do the best that you can do and it was really difficult to draw the line between being Mammy and being at home, but also having a work identity” (p. 6). Other studies suggested that lack of WLB led to feeling overwhelmed. A participant in Hjálmsdóttir and Bjarnadóttir’s (2021) study described feeling overwhelmed as, “I do not sit down, but still the apartment is in chaos, the children neglected, and work unfinished” (p. 275).

Anger was also reported in two studies with women participants who experienced unequal division of housework and care work (Craig, 2020; Parlak et al., 2021). A woman participant in Parlak et al.’s (2021) study shared, “A feeling of anger comes out. Moreover, the fact that he does not understand me and what I do is upsetting. Because he said once, “You do not work at home.” If I do nothing, then who does all of the housework?” (p. 16). As found in four studies the psychological well-being of women was likely to be affected negatively due to the disproportionate increase in housework and care work responsibilities (Clark et al., 2020; Hennekam & Shymko, 2020; Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, 2021; Shockley et al., 2021). Only three studies discussed the advantages of working from home and the subsequent well-being, including less stress and less emotional exhaustion, due to not commuting and to receiving employer support (Carillo et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021).

Work Outcomes

Eleven studies highlighted that the challenge of balancing paid work, housework, and care work simultaneously while working from home was an impediment to work productivity and performance (Burk et al., 2020; Hennekam & Shymko, 2020; Hertz et al., 2020; Parlak et al., 2021; Toscano & Zappalà, 2020; Vaziri et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021). A participant in Burk et al.’s (2020, p. 5) study declared, “I’ve been struggling to get my work done, honestly. My wife and I split up the day so that we could educate and care for our kids.” With competing demands from work and nonwork, some participants, as mentioned in one study, made a conscious choice to delay work commitments to attend to children (Clark et al., 2020). Shockley et al.’s (2021) study suggested that women participants who worked from home and did the lion’s share of the domestic work had the lowest job performance compared to those from households that adopted more egalitarian strategies.

A few studies found that working from home improved WLB and work efficiency because individuals could utilize the time and energy saved from commuting to spend quality time with family members and focus on work tasks (Craig, 2020; Ipsen et al., 2021). Also, employees who received support from their managers and employers had less difficulty with balancing work and family demands, and reported high work performance (Wang et al., 2021).

Two studies also showed that the lack of WLB and feelings of isolation while working from home led to lower job satisfaction (Toscano & Zappalà, 2020; Vaziri et al., 2020) and higher turnover intention (Vaziri et al., 2020). Also, one study suggested that employees worried that attending to nonwork demands and looking unbalanced while working from home would look unprofessional (Clark et al., 2020). A participant from Clark et al.’s (2020) study shared a similar sentiment, “I was on many calls where like my boss would say, do you want to go and sort that house because you could hear the fighting from 2 rooms away” (p. 6).

Family Outcomes

Seven studies focused on family outcomes, including intimacy, cohesion, family tension and conflict, and tensions in partner and parent-child relationships. Two studies reported that people working from home during the pandemic experienced intimacy and increased family cohesion when they took the opportunity to bond with family members (Behar-Zusman et al., 2020; Parlak et al., 2021). However, four studies reported increased family tension and conflict when participants worked from home (Ayuso et al., 2020; Goldberg et al., 2021; Parlak et al., 2021; Trougakos et al., 2020). Increased re-organisation of domestic work, a lot of togetherness, and lack of alone time contributed to increased relational strain between partners (Goldberg et al., 2021; Shockley et al., 2021). Having to work and study at home with other family members all day also created tension in parent-child relationships (Hertz et al., 2020; Parlak et al., 2021). A mother in Hertz et al.’s (2020) study shared, “Being stuck at home has been awful for both of us. She [the daughter] has major tantrums every day and I am trying to work from home” (p. 19). Similarly, a participant from Parlak et al.’s (2021) study shared, “I lose my patience and do not have the energy after a while. I have arguments with my son. I yell at him, and he yells at me. We argue about anything” (p. 12).

Career Outcomes

Six studies suggested that loss of productivity and performance due to a lack of WLB while working from home made employees anxious about career outcomes that could be associated with such loss (e.g., Clark et al., 2020; Minello et al., 2021). Working mothers with children who had reorganised their job priorities during the pandemic to suit their family needs were particularly worried and concerned about how the situation was unfavourable to their career progression (Hertz et al., 2020; Minello et al., 2021). An academic shared how she could not afford to focus on tasks that were crucial for promotion. “Writing is the very last thing I’m doing. In fact, I’m not doing it … things that let’s say didn’t have deadlines, weren’t on a review path, I’m not doing those things. I make calls, meetings, teaching once a week and correcting reports for a European project deadline, and so I’m up to my neck in water” (Minello et al., 2021, p. S88).

Three studies showed that employees were concerned that having a low performance while working from home during the pandemic may have negative implications for their employment (Akuoko et al., 2021; Hertz et al., 2020; Minello et al., 2021; Petts et al., 2021). One reviewed study indicated that mothers had to devote a significant amount of time to care work during the pandemic, which put them at a greater risk of losing their jobs (Petts et al., 2021). A participant in Hertz et al.’s (2020) study expressed such risk as, “I did ask for a lot of help/understanding from work but [I] am concerned this made me seem weak and unable to cope.” Similarly, a participant in Minello et al.’s (2021) study shared how the situation put her at risk of losing her employment, “I was supposed to get my license now in May, I was supposed to write something important about a show that has to open. None of that [happened]” (p. 12).

Discussion

Drawing on our review of the extant literature, we offer an integrative model that contextualizes the antecedents and outcomes of WLB while working from home during the pandemic. Informed by COR theory, the proposed model identifies not only the hindrances and challenges facing employees working from home that led to stressors, but also the resources that facilitated their WLB. Drawing together a list of work and nonwork antecedents that reflect work from home contingencies sheds light on the underexplored factors in previous reviews. The negative impact of work and nonwork resource loss antecedents on WLB of employees working from home signals the pervasive role of resource loss and stress, which, according to COR theory, is more salient than resource gain (Hobfoll, 2011). Resource gain was most likely when employees working from home were supported by supervisors and family members, received job autonomy, and demonstrated personal adaptability.

In our review, in both work and nonwork domains, the number of stressors outweighed resources. This pattern can be explained by COR theory, which suggests that stressors is more profound than resources in the broad life context. Also, work from home during the pandemic contributed to the emergence of more stressors, where access to help for domestic work was limited and workers had to shift to work from home with limited preparation. Based on our findings, we suggest future research to explore the weight of stressors on individuals’ overall pool of personal resources and how different resources enable coping with each stressor. We also suggest that future researchers examine the interactions between stressors and resources, as well as the moderating effects of resources in the relationships between stressors and WLB.

In terms of the countries in the research included in our review, employees residing in high-income and developed countries were frequently studied. This may be because of researchers’ better access to research support in developed countries that can result in a quicker adjustment to the pandemic and speedier data collection and publication. Also, this pattern resembles the extant work-family literature where most previous research has been conducted in developed countries (e.g., Shockley et al., 2017). Nonetheless, the inclusion of five middle-income and low-income countries provides initial information for future research. We speculate that the lack of focus on WLB while working from home during the pandemic in less developed countries may be due to the lack of readiness for work from home. For example, working from home calls for technological infostructure and tools such as high-speed internet, computers, software, applications, and digital devices, which may be limited in some developing countries. In addition, as the research on virtual teams (Raghuram et al., 2019) suggests, the experience of working in virtual settings has predominantly advanced in developed countries for the past several years. It is possible to assume that maybe during the pandemic, employees and employers in developed countries were familiar with and relatively ready to switch to work from home, whereas in the developing countries the option of work from home was less available. We invite future research to employ samples from developing countries to maximize the chances of uncovering different stressors and resources among those working from home. We also suggest that researchers attempt to understand how the use of work from home may function differently in developing and developing countries by conducting cross-cultural studies.

Most of the participants in the reviewed studies worked in white-collar jobs (e.g., accountants, engineers, managers, administrative staff) for which work from home can be an option. As a result, our review does not reflect the WLB issues of occupations for whom working from home was not feasible, such as blue-collar workers in shipping and delivery) and frontline workers. Baskin and Bartlett’s (2021) review examined the research concerning healthcare workers and found that the frontline workers faced stress due to a high rate of infection, inadequate personal protective equipment, and the lack of available hospital beds. In comparison, our review informs researchers and practitioners about the dynamics of stressors and resources involved in working from home. Despite our focus on working from home, we do acknowledge that the WLB experiences of those who could not work from home during the lockdown have been equally important and require research attention.

Future research needs to consider stressors, resources, and WLB among vulnerable groups of employees working from home, including single parents, individuals caring for the elderly, and employees with disabilities to voice their needs and concerns when necessary (Bierema, 2020). For example, single employees may be especially vulnerable to perceived work intensity and isolation without the support of family members. Future studies may adopt a critical lens to examine the effects of the pandemic on changing the gendered patterns with regards to assuming responsibility for the nonwork domain and increased expectations from the mothers and women who had to take up extra burdens of housework, childcare, and emotional demands during this period. A few studies in our review suggested that the partners working from home during the pandemic reverted to traditional gender roles—men prioritized work and career and women were left to take care of the housework and childcare responsibilities—which contributed to deepening gender inequalities. At the same time, some studies acknowledged that working from home during the pandemic created opportunities for men to be more engaged in housework and care work, which contributed somewhat to narrowing the gender gaps. These pattens suggest that work from home of couples and families may have the potential to both reinforce traditional gender roles or to transcend traditional gender roles and promote egalitarian approaches. Very few of the studies engaged both partners in data collection to provide an opportunity for comparison of perspectives, which future researchers may pursue.

The unprecedented situation of the pandemic, and the sense of urgency for conducting research to capture its nuances, might justify the prevalence of single source data used in the studies we reviewed. Given that work from home has a variety of arrangements and can be a collective experience in many households, we encourage future researchers to collect multiple formats of data from varying stakeholders to gain a more in-depth understanding of work from home and other home-working stakeholder experiences. Finally, our review reflects the experiences of home workers who utilize ICT, mostly white-collar professionals employed by informal organizations and institutions. Future review studies may look into the experience of home-based workers who may be low-skilled, self-employed, or independent contractors.

Theoretical Implications

Our integrated model indicates COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2011) as a point of departure to guide future research that intends to examine the dynamics of WLB while working from home. In what follows, we discuss the two vicious and virtuous cycles that were not addressed in the literature but might be useful for future research. We suggest that stressors and resources that impact WLB and other outcomes are dynamically and reciprocally related to each other, thus creating a vicious loss cycle and a virtuous gain cycle, respectively (see Figure 2).

First, the notion of loss cycle based on COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2011) suggests that initial resource loss brings future loss. In other words, being exposed to stressors makes the individuals more vulnerable to experiencing more stress in the future. Based on this notion, we argue that resource loss initiated by work from home may be associated with decreased WLB, which could cause further resource loss as far as well-being, work, career, and family outcomes. In other words, loss of resources while working from home that lead to imbalance can have detrimental effects on employees. Although a few of the studies we reviewed discussed these connections, there is still an urgent need for more research to identify the cyclical mechanisms through which loss of resources in work and nonwork domains while working from home impacts WLB and eventually well-being, work, career, and family outcomes for employees working from home.

Second, COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2011) states that initial resource gain facilitates the possibility of further resource gain. In other words, resources help individuals preserve their personal resources sufficiently to acquire further resources to protect their well-being. Based on this principle, employees working from home who receive resources such as job autonomy and organizational support are more likely to be able to gain further resources such as positive energy and time that lead to WLB and other positive outcomes. Because COR theory notes that resource loss is more potent than gain, loss cycles will be more impactful than gain cycles. Therefore, in the wake of crisis situations such as the pandemic or severe resource loss, individuals and families seek to both repair the damage and to mobilize resources to prevent further loss. Workplaces and organizations can play an important role by providing resources to trigger the gain cycle. Future researchers may examine how negative and unintended well-being, career, work, and family outcomes trigger proactive responses to gain resources. To study the dynamic and cyclical interplay between resources loss and gain, there is a need for theory-grounded longitudinal studies that assess antecedents of WLB over time. Such studies have been absent in the current literature, especially when both stressors and resources associated with working from home are considered.

Finally, using COR theory helped us overcome some limitations of other theories used in studies of WLB and its antecedents and outcomes. We invite future researchers to consider COR theory because it enables incorporating the broader life context of individuals compared to theories that only focus on the job-related context (e.g., job demands-resources model; Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Also, as opposed to traditional stress theories concentrating on individual appraisals of stressful situations as the antecedents of stress and WLB, COR theory draws attention to the environmental, social, and cultural bases of demands and stressors. It brings resources to researchers’ attention to explain what people need to acquire or protect to ensure their well-being and distance themselves from stressors. We extend the COR theory by providing a nuanced and contextualized understanding of stressors and resources that emanate from the challenge of achieving WLB while working from home during the pandemic.

Practical Implications

Corresponding with HRD’s commitments to employee and organization performance and well-being (e.g., Fenwick & Bierema 2008; Holton 2002; Kuchinke, 2010; McGuire et al. 2021), our review offers the HRD community insights into the current knowledge that could be utilized to improve remote workers’ WLB. We encourage employers who adopt work from home arrangements to be mindful of the effects of stressors and resources outlined in our review. As work plays an important role in these processes, employers and managers need to identify, understand, and reduce the likelihood of circumstances that lead to perceived work intensity, technostress, and professional isolation. Also, employers and HRD practitioners need to consider workspace at home and the level of interdependence of work tasks when making decisions about work from home assignments and schedules. To take proactive steps toward improving WLB of employees working from home and other outcomes, employers and HRD practitioners may enrich supervisors’ and leaders’ roles, so they can extend job autonomy and provide various types of support, including tangible help with ICT, timely information, relevant work materials, and social support. We recommend interventions, such as financial support for childcare and domestic help to allow employees, especially mothers and parents, to accommodate managing housework and childcare intensity while working from home. Other solutions to help reduce resource loss while working from home include ensuring reasonable workloads, sufficient and designated workspace at home, ICT training and support, adequate tools and access to stable internet, and simple and user-friendly technology and platforms for work from home. Managers and supervisors may also invest in improving communication and take action to ensure work colleagues socialize and connect regularly, and that employees working from home are included in all activities to avoid isolation. Finally, employers and HRD practitioners may provide employees with training to improve their adaptability, including their ability to manage work-nonwork boundaries and to fit their demands to available resources, and they may coach their managers and supervisors to understand the demands of work from home and the resources employees need to stay balanced (See Appendix E for a list of practical suggestions for organizations and managers).

Limitations

As with any study, our review has limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, to identify the antecedents of WLB while working from home, we included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies, which limited our ability to derive and quantify conclusions about the strength of the relationships between factors. The application of some of the identified WLB antecedents and outcomes may be limited to crisis times, since most of the studies were conducted and published when the pandemic was ongoing, and lockdowns and school closures were in place. Third, we only reviewed studies that were published in English and were indexed in the Web of Science database. Fourth, it is important to note that almost all the reviewed studies examined correlational relationships or qualitative associations between WLB and its antecedents and outcomes; therefore, while relationships were often described as direct links, causal effects are yet to be confirmed.

Conclusion

Our paper provides a timely contribution to our understanding of work from home, which has become more prevalent during the pandemic. Our findings extend the literature on WLB by presenting a model informed by COR theory and integrating resource loss and gain mechanisms. We explain how WLB can be impacted by both stressors and resources while working from home. We offer practical implications to organizations and managers, building on a systematic examination of the pandemic-induced empirical studies involving employees working from home.

Author Biographies

Melika Shirmohammadi is an Assistant Professor of HRD at University of Houston. Her research encompasses the Careers and Work-Nonwork Interface of immigrants, academics, women, and understudied populations. Her work has appeared in Journal of Vocational Behavior, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, and Applied Psychology: An International Review among others. Melika serves as an Assistant Editor to HRD Quarterly, an Editorial Board Member to HRD Review; and HRD International.

Wee Chan Au is a Lecturer in Management Practice at Newcastle University. Her research focuses on WLB and wellbeing at workplace, and organizational practices that facilitating employee wellbeing. Her work has appeared in Journal of Business Ethics, Personnel Review, HRD International, European Business Review, and Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An international Journal.

Mina Beigi is an Associate Professor of OB and HRM in Southampton Business School, University of Southampton. Mina studies work-nonwork interface, career success, and understudied careers using in-depth qualitative methodologies. Her work has been published in Human Relations, Journal of Vocational Behavior, International Journal of Management Reviews, Applied Psychology: An International Review, and The International Journal of Human Resource Management, among others. Mina has served as the Associate Editor of HRD Review 2017–2020; she currently serves as the Associate Editor of Human Relations.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Detailed Comparison Between the Current Paper and Shirmohammadi et al. (2022).

| Current paper | Shirmohammadi et al. (2022) | |

|---|---|---|

| Title | Antecedents and outcomes of work-life balance while working from home: A review of the research conducted during the pandemic | Remote work and work-life balance: Lessons learned from the pandemic and suggestions for HRD practitioners |

| Focus | • Antecedents and outcomes of WLB while

working from home • Connections among WLB and its antecedents and outcomes |

• The perceptions of remote working as a

desirable work arrangement vs undesirable aspects

surfaced during the pandemic • Suggestions for HRD practitioners or lessons from the widespread involuntary remote work |

| Theoretical framework | Conservation of resources theory | Person-environment fit theory |

| Theoretical contributions | • A conceptual framework that organizes the

antecedents and outcomes of WLB based on resource loss

and gain • The conceptual framework helps to theoretically explain the dynamic interplay of stressors and resources that impact WLB and its outcomes • Contextualizing WLB and its antecedents and outcomes for the work from home context |

• 4 desirable and 4 undesirable aspects of remote work |

| Practical contributions | • 22 practical implications for (a) organizations, (b) managers, and (c) employees | • 7 suggestions that can help HRD practitioners who intend to (a) offer remote work as an option, (b) prepare to support transition and remote work, and (c) provide ongoing support to sustain remote work |

| Methods | • 48 studies conducted between March 2020 and March 2022 | • 40 empirical studies published between

March, 2020, and August, 2021 • The dataset was complemented with 9 literature reviews and meta-analyses that examined WLB and flexible work arrangements conducted prior to the pandemic |

| Analysis approach | • 48 studies coded into a literature review

matrix (Garrard,

2017) • Dividing the sample into quantitative and qualitative findings and recoding the links among WLB, its antecedents, and outcomes. |

• Thematic analysis of the 40 articles and

previous reviews and meta-analyses • Comparison between the pandemic-induced literature with findings from pre-pandemic literature reviews |

| Findings (main themes) | Stressors and WLB while working from

home • Work domain stressors • Nonwork domain stressors Resources and WLB while working from home • Work domain resources • Nonwork domain resources Outcomes of WLB while working from home |

Desirable aspects of remote work • Flextime • Flexplace • Technologically-feasible • Family-friendly Undesirable aspects of remote work • Work intensity • Space limitation • Technostress and isolation • Housework and care intensity |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Preview of the Reviewed Studies

| Authors & year | Type of study | Country | Categories | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Akuoko et al., 2021 | Quantitative | Ghana | Work outcomes, career outcomes, well-being, perceived work intensity, housework intensity, care work intensity |

| 2 | Allen et al., 2021 | Quantitative | USA | Workspace limitation, family support, personal adaptability |

| 3 | Ayuso et al., 2020 | Quantitative | Spain | Workspace limitation, housework intensity, care work intensity, emotional demands, family outcomes |

| 4 | Becker et al., 2022 | Quantitative | USA | Professional isolation, job autonomy, well-being |

| 5 | Behar-Zusman et al., 2020 | Quantitative | 81 different countries in the continents of Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America | Family outcomes |

| 6 | Beri, 2021 | Quantitative | India | Family support, well-being |

| 7 | Bhumika, 2020 | Quantitative | India | organizational support, well-being |

| 8 | Biron et al., 2020 | Quantitative | China, Germany, Israel, Netherlands, and USA. | Personal adaptability |

| 9 | Burk et al., 2020 | Qualitative | USA | Perceived work intensity, care work intensity, work outcomes |

| 10 | Carillo et al., 2021 | Quantitative | France | Workspace limitation, technostress work interdependence, professional isolation, housework intensity, care work intensity, emotional demands, Job autonomy |

| 11 | Chong et al., 2020 | Quantitative | Singapore | Work interdependence, emotional demands, organizational support, job autonomy, well-being |

| 12 | Chung et al., 2021 | Quantitative | UK | Housework intensity, care work intensity |

| 13 | Clark et al., 2020 | Qualitative | Ireland | Care work intensity, emotional demands, family support, work outcomes, career outcomes, well-being |

| 14 | Costoya et al., 2021 | Quantitative | Argentina | Housework intensity, care work intensity |

| 15 | Craig, 2020 | Quantitative | Australia | Workspace limitation, housework intensity, care work intensity |

| 16 | Craig & Churchill, 2021 | Quantitative | Australia | Perceived work intensity, housework intensity, care work intensity |

| 17 | Dandalt, 2021 | Qualitative | Canada | Perceived work intensity, technostress, work interdependence, professional isolation, organizational support, well-being |

| 18 | Del Boca et al., 2020 | Quantitative | Italy | Perceived work intensity, housework intensity, care work intensity, family support |

| 19 | Gashi et al., 2021 | Quantitative | Kosovo | Technostress, organizational support, work outcomes |

| 20 | Giauque et al., 2022 | Quantitative | Switzerland | Work interdependence, organizational support, job autonomy, work outcomes, well-being |

| 21 | Goldberg et al., 2021 | Mixed-methods | USA | Housework intensity, care work intensity, emotional demands, well-being, family outcomes |

| 22 | Hennekam & Shymko, 2020 | Qualitative | France | Care work intensity, emotional demands, work outcomes, well-being |

| 23 | Hertz et al., 2020 | Quantitative | Canada & USA | Perceived work intensity, workspace limitation, care work intensity, family support, work outcomes, career outcomes, well-being, family outcomes |

| 24 | Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, 2021 | Qualitative | Iceland | Housework intensity, care work intensity, emotional demands, well-being |

| 25 | Ipsen et al., 2021 | Quantitative | 29 European countries | Technostress, professional isolation, emotional demands, job autonomy, work outcomes |

| 26 | Karl et al., 2021 | Qualitative | Not specified | Workspace limitation |

| 27 | Kerman et al., 2021 | Quantitative | Slovenia, Germany, Austria & Netherlands | Personal adaptability |

| 28 | Lamprinou et al., 2021 | Quantitative | Greece | Organizational support |