Key Points

Question

What is the risk of aortic dissection (AD) and all-cause death for nonsyndromic patients with unrepaired ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA), overall and by TAA size?

Findings

In this cohort study, the overall absolute risk of AD was low. Although the risk of AD and all-cause death was associated with larger aortic sizes, there was an inflection point at 6.0 cm.

Meaning

The findings in this study support consensus guidelines recommending surgical intervention at 5.5 cm in nonsyndromic patients with TAA; earlier prophylactic surgery should be done only selectively in the nonsyndromic population, given the nontrivial risks associated with aortic surgery.

This cohort study assesses the association between ascending thoracic aorta aneurysm size and patient outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

The risk of adverse events from ascending thoracic aorta aneurysm (TAA) is poorly understood but drives clinical decision-making.

Objective

To evaluate the association of TAA size with outcomes in nonsyndromic patients in a large non–referral-based health care delivery system.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Kaiser Permanente Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm (KP-TAA) cohort study was a retrospective cohort study at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, a fully integrated health care delivery system insuring and providing care for more than 4.5 million persons. Nonsyndromic patients from a regional TAA safety net tracking system were included. Imaging data including maximum TAA size were merged with electronic health record (EHR) and comprehensive death data to obtain demographic characteristics, comorbidities, medications, laboratory values, vital signs, and subsequent outcomes. Unadjusted rates were calculated and the association of TAA size with outcomes was evaluated in multivariable competing risk models that categorized TAA size as a baseline and time-updated variable and accounted for potential confounders. Data were analyzed from January 2018 to August 2021.

Exposures

TAA size.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Aortic dissection (AD), all-cause death, and elective aortic surgery.

Results

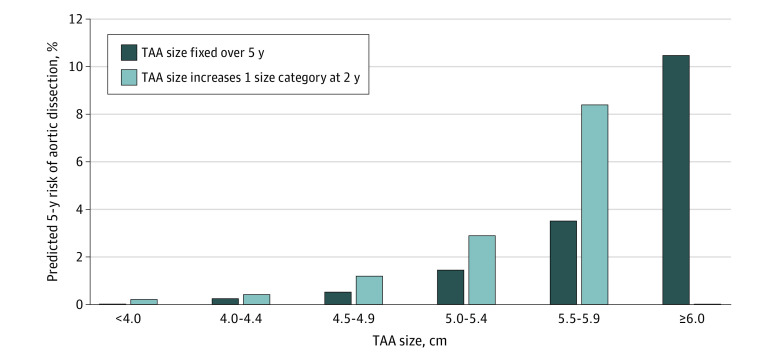

Of 6372 patients with TAA identified between 2000 and 2016 (mean [SD] age, 68.6 [13.0] years; 2050 female individuals [32.2%] and 4322 male individuals [67.8%]), mean (SD) initial TAA size was 4.4 (0.5) cm (828 individuals [13.0% of cohort] had initial TAA size 5.0 cm or larger and 280 [4.4%] 5.5 cm or larger). Rates of AD were low across a mean (SD) 3.7 (2.5) years of follow-up (44 individuals [0.7% of cohort]; incidence 0.22 events per 100 person-years). Larger initial aortic size was associated with higher risk of AD and all-cause death in multivariable models, with an inflection point in risk at 6.0 cm. Estimated adjusted risks of AD within 5 years were 0.3% (95% CI, 0.3-0.7), 0.6% (95% CI, 0.4-1.3), 1.5% (95% CI, 1.2-3.9), 3.6% (95% CI, 1.8-12.8), and 10.5% (95% CI, 2.7-44.3) in patients with TAA size of 4.0 to 4.4 cm, 4.5 to 4.9 cm, 5.0 to 5.4 cm, 5.5 to 5.9 cm, and 6.0 cm or larger, respectively, in time-updated models. Rates of the composite outcome of AD and all-cause death were higher than for AD alone, but a similar inflection point for increased risk was observed at 6.0 cm.

Conclusions and Relevance

In a large sociodemographically diverse cohort of patients with TAA, absolute risk of aortic dissection was low but increased with larger aortic sizes after adjustment for potential confounders and competing risks. Our data support current consensus guidelines recommending prophylactic surgery in nonsyndromic individuals with TAA at a 5.5-cm threshold.

Introduction

It is well established that ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) can predispose patients to aortic dissection (AD),1,2,3,4 a life-threatening event with high morbidity and mortality.5,6,7 However, controversy exists regarding the appropriate size for prophylactic aortic intervention,8,9,10 partly due to an incomplete understanding of the natural history of TAA. Limitations of prior natural history studies include being performed mostly in referral-based populations, potential lack of comprehensive follow-up, and small numbers of patients with unoperated moderate and large aneurysms with longitudinal follow-up.1,3,4,11,12

Professional society guideline recommendations have varied over time, with changing TAA size thresholds for operative intervention,13,14,15 and the absence of definitive clinical trial evidence combined with frequent prophylactic repair in current practice has limited the longitudinal data available for patients with moderate and severely dilated aneurysms. This presents treating clinicians with a dilemma: there are minimal data to guide conservative management strategies or counsel patients with TAA size 5.0 cm or larger, as surgical intervention should be offered only when the risk of dissection and death from the unrepaired aneurysm outweighs the surgical risk. Further, even among patients with aneurysms smaller than 5.0 cm, the data guiding decision-making are limited.

To address this evidence gap, we examined the natural history of TAA in a large integrated health care delivery system (Kaiser Permanente Northern California [KPNC]) in the Kaiser Permanente Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm (KP-TAA) cohort study. We estimated the risks of AD, death, and surgical intervention in patients with TAAs of varying sizes to better understand the natural history of TAA, particularly among those with larger aneurysms.

Methods

Data Source

The source population included members of KPNC, a large integrated health care delivery system insuring and providing care for more than 4 500 000 persons. Its membership is highly representative of the local and statewide population with regard to age, sex, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.16 KPNC provides comprehensive inpatient, emergency department, and outpatient care for a large proportion of insured adults across Northern California, with nearly all care captured through its electronic health record (EHR) system, which is integrated across all practice settings. This study was approved by the KPNC institutional review board. Waiver of informed consent was obtained due to the nature of the study. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Study Population

In the mid-2000s, a KPNC regional safety net system for patients with TAA, the Population and Conditions Tracking System (PACTS), was developed to ensure appropriate surveillance imaging for patients with dilation of the aortic root, ascending aorta, and aortic arch (both mild dilation and those with larger aneurysms; henceforth, patients with TAA). Patients were entered into the surveillance system through automated daily electronic searches of the KPNC EHR for relevant International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and Tenth Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9/10-CM) codes for TAA or through manual entry of patients referred for TAA evaluation and treatment to 1 of 3 cardiovascular surgery centers across Northern California. This safety net system included clinical documentation by registered nurses of key clinical details, radiology reports, overreading of radiology reports by supervising cardiothoracic surgeons, and other relevant patient information. Imaging studies reviewed included computed tomography studies, echocardiograms, and magnetic resonance imaging.

Four physician reviewers (M.D.S., J.C., A.T., P.V.) abstracted the clinical documentation from the PACTS system using a standardized structured data element form. Quality control was performed by having an adjudicating board-certified cardiologist (M.D.S.) review a sample of each reviewer’s abstractions and settle any disputed or unclear entries. Abstracted data elements from PACTS included confirmation of ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm (aortic root, ascending aorta, or aortic arch up to the left subclavian artery), imaging study date, maximum aortic size, and type of imaging modality (when available).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We identified patients in the PACTS system from 2000 to 2016. Patients were included in our study if they had at least 1 imaging study with TAA 3.5 cm or larger, were older than 18 years, had no known prior AD or aortic surgery, and had known age, sex, and active health plan membership at the time of TAA diagnosis.

We excluded all patients with known predisposition to TAA (ie, Turner syndrome, Marfan syndrome, vascular Ehlers Danlos syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, and other hereditary thoracic aortic syndromes) identified using a combination of manual review of health plan databases, including registries from cardiovascular genetics clinics, in combination with searches of relevant ICD-9/10-CM codes (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

Index Date and Follow-Up

Index date was defined as the date of the first qualifying TAA imaging study in eligible patients. Follow-up occurred through December 2016 with censoring for health plan disenrollment, organ transplant, or death. Data were analyzed from January 2018 to August 2021.

Covariates

We used health plan administrative and clinical data, pharmacy databases, and laboratory databases from our comprehensive KPNC EHR to obtain baseline demographic characteristics, medications, laboratory values, and vital signs for the study population (eMethods in Supplement 1). We included race and ethnicity to reflect the diversity of the cohort and to evaluate differences in study outcomes that may be present across different racial and ethnic groups. Using validated algorithms,17,18,19,20,21 we identified multiple relevant comorbid conditions before the index date. Patients with bicuspid aortic valve were identified using natural language processing techniques applied to KPNC echocardiography reports.22 Using pharmacy databases, we also identified receipt of relevant medications before the index date. We also ascertained the most recent outpatient estimated glomerular filtration rate,20 low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycosylated hemoglobin, body mass index, blood pressure, and heart rate measurements from EHR data.

Outcomes of Interest

Primary outcomes included type A aortic dissection events (including intramural hematoma and aortic rupture events), which were identified through ICD-9/10-CM diagnosis codes, abstracted data from the PACTS system, and all final events in the analysis were manually adjudicated through medical record and imaging review by a board-certified cardiologist; a composite outcome of AD or all-cause death, the latter being identified from EHR data, Social Security Administration vital status records, and California death certificates—an approach that has yielded greater than 97% vital status information in prior studies18; and aortic surgery based on ICD-9/10-CM and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and R version 3.6.0 (R Foundation), with 2-sided P < .05 considered significant. Characteristics of patients with different initial TAA size values were compared using analysis of variance or relevant nonparametric test for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

We calculated unadjusted rates (per 100 person-years) of AD and the composite outcome of AD and death, stratified by initial TAA size. Follow-up time was censored at the date of aortic surgery (among those who had surgery) to ensure the at-risk time included only unrepaired TAA and death or disenrollment. We also analyzed outcomes in a time-updated manner, allowing patients to be reclassified into TAA size bins based on each new imaging study across follow-up. In this analysis, the outcome of AD or death was attributed to the most recent TAA size prior to the event, and the time at risk within each aortic size bin began at the date of each new imaging study and extended until the next imaging study or censoring event. We estimated cumulative incidence curves using the Kaplan-Meier estimator, stratified by initial TAA size.

We estimated the association of baseline and time-updated TAA size with AD and the composite outcome of AD and all-cause death using multivariable proportional hazards competing risk models.23 Using results from the time-updated TAA size models, we estimated predicted 5-year probabilities of these outcomes for patients in whom TAA size remained constant over 5 years and for those who had an increase in TAA size by 1 size category at 2 years. We estimated 95% confidence intervals using bootstrapping with 10 000 bootstrapped data sets. Risk prediction using time-updated covariates requires the specification of the covariate trajectories over time, and we considered the case where TAA size remains constant over 5-year follow-up and where TAA increases in size by 1 category at 2 years.

To assess whether absolute aortic size differed in predictive power compared to aortic size indexed by height and weight, we compared our models to models that substituted aortic size categories with categories for the aortic size index based on previously validated methods12 dividing aortic size by body surface area, and compared C statistics for the models.24

Results

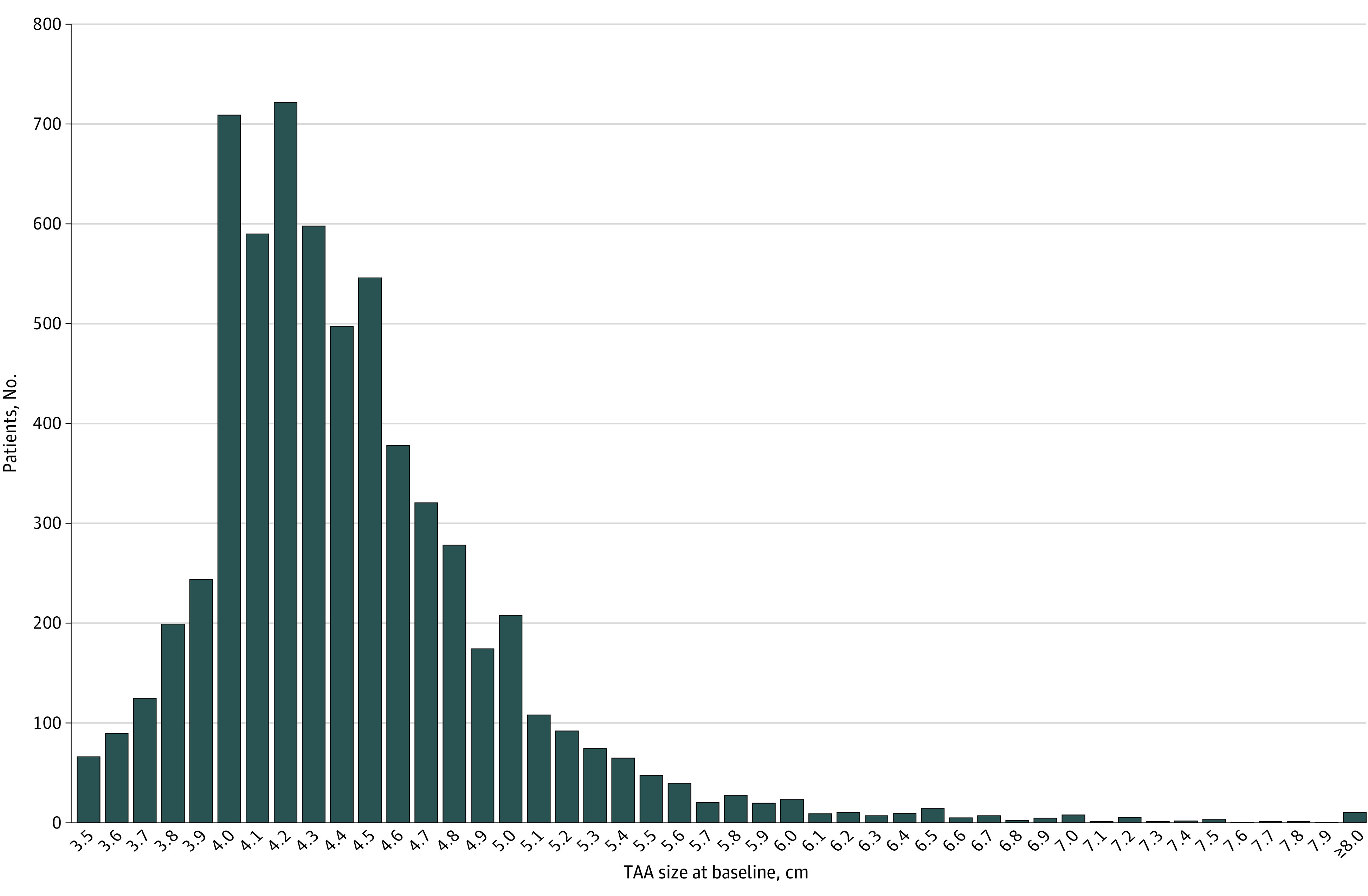

We identified 6372 eligible patients with TAA from 2000 to 2016 (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1 and eTable 2 in Supplement 1. The mean (SD) age was 68.6 (13.0) years overall and slightly higher in the largest TAA size category (72.1 [15.3] years in those with TAA size 6.0 cm or larger). There were roughly twice as many male individuals in each TAA size category, with 2050 female individuals (32.2%) and 4322 (67.8%) male individuals in the total cohort. By patient self-report, 384 individuals (6.0%) were African American or Black, 845 (13.3%) were Asian or Pacific Islander, 4362 (68.5%) were White, 511 (8.0%) were of Hispanic ethnicity, 420 (6.6%) were of another race or ethnicity (including Native American or Alaska Native and those who reported multiple races or ethnicities, combined owing to small numbers in the former and the inability to disaggregate data in the latter), and 361 (5.7%) were of unknown race or ethnicity. There were significant numbers of patients at every category of initial TAA size, including 828 patients (13.0%) with TAA size 5.0 cm or larger and 280 (4.4%) with TAA size 5.5 cm or larger at diagnosis (Figure 1). The mean (SD) TAA size at diagnosis was 4.4 (0.5) cm with a median (IQR) size of 4.3 (4.1-4.7) cm. Mean (SD) follow-up was 3.7 (2.5) years with a median (IQR) follow-up of 3.2 (1.7-5.3) years. Comorbidity burden was typical for the age group, with 4381 individuals in the cohort (68.8%) having a prior diagnosis of hypertension. However, only 974 patients (15.3%) had systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg at the time of TAA diagnosis. Bicuspid aortic valve was present in 747 individuals (11.2% of the cohort).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm (TAA).

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 6372) | Initial TAA size, cm | |||||||

| 3.5-3.9 (n = 726) | 4.0-4.4 (n = 3120) | 4.5-4.9 (n = 1698) | 5.0-5.4 (n = 548) | 5.5-5.9 (n = 156) | ≥6.0 (n = 124) | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 68.6 (13.0) | 67.9 (13.6) | 68.3 (12.7) | 68.8 (13.0) | 69.3 (13.3) | 68.4 (13.5) | 72.1 (15.3) | .01 |

| Female | 2050 (32.2) | 339 (46.7) | 1004 (32.2) | 468 (27.6) | 140 (25.5) | 50 (32.1) | 49 (39.5) | <.001 |

| Male | 4322 (67.8) | 387 (53.3) | 2116 (67.8) | 1230 (72.4) | 408 (74.5) | 106 (67.9) | 75 (60.5) | |

| Race, No. (%)a | ||||||||

| African American or Black | 384 (6.0) | 51 (7.0) | 207 (6.6) | 77 (4.5) | 32 (5.8) | 6 (3.8) | 11 (8.9) | .09 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 845 (13.3) | 107 (14.7) | 441 (14.1) | 210 (12.4) | 59 (10.8) | 16 (10.3) | 12 (9.7) | |

| White | 4362 (68.5) | 485 (66.8) | 2085 (66.8) | 1199 (70.6) | 397 (72.4) | 114 (73.1) | 82 (66.1) | |

| Otherb | 420 (6.6) | 43 (5.9) | 209 (6.7) | 115 (6.8) | 30 (5.5) | 12 (7.7) | 11 (8.9) | |

| Unknown | 361 (5.7) | 40 (5.5) | 178 (5.7) | 97 (5.7) | 30 (5.5) | 8 (5.1) | 8 (6.5) | |

| Hispanic ethnicitya | 511 (8.0) | 57 (7.9) | 247 (7.9) | 141 (8.3) | 42 (7.7) | 13 (8.3) | 11 (8.9) | .99 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||

| Current | 528 (8.3) | 59 (8.1) | 265 (8.5) | 129 (7.6) | 41 (7.5) | 18 (11.5) | 16 (12.9) | <.001 |

| Former | 2533 (39.8) | 302 (41.6) | 1273 (40.8) | 661 (38.9) | 196 (35.8) | 56 (35.9) | 45 (36.3) | |

| Passivec | 33 (0.5) | 5 (0.7) | 13 (0.4) | 8 (0.5) | 5 (0.9) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Never | 3125 (49.0) | 349 (48.1) | 1523 (48.8) | 849 (50.0) | 276 (50.4) | 73 (46.8) | 55 (44.4) | |

| Unknown | 153 (2.4) | 11 (1.5) | 46 (1.5) | 51 (3.0) | 30 (5.5) | 8 (5.1) | 7 (5.6) | |

| Baseline history of comorbidities | ||||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 233 (3.7) | 33 (4.5) | 108 (3.5) | 62 (3.7) | 20 (3.6) | 5 (3.2) | 5 (4.0) | .83 |

| Unstable angina | 44 (0.7) | 4 (0.6) | 25 (0.8) | 11 (0.6) | 3 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | .84 |

| Ischemic stroke or TIA | 289 (4.5) | 34 (4.7) | 146 (4.7) | 82 (4.8) | 18 (3.3) | 3 (1.9) | 6 (4.8) | .42 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 665 (10.4) | 71 (9.8) | 327 (10.5) | 169 (10.0) | 55 (10.0) | 18 (11.5) | 25 (20.2) | .02 |

| Mitral or aortic valvular disease | 1246 (19.6) | 104 (14.3) | 489 (15.7) | 404 (23.8) | 173 (31.6) | 44 (28.2) | 32 (25.8) | <.001 |

| Atrial flutter or fibrillation | 1221 (19.2) | 111 (15.3) | 574 (18.4) | 368 (21.7) | 115 (21.0) | 28 (17.9) | 25 (20.2) | .006 |

| Heart failure | 727 (11.4) | 60 (8.3) | 323 (10.4) | 208 (12.2) | 84 (15.3) | 28 (17.9) | 24 (19.4) | <.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass surgery | 18 (0.3) | 4 (0.6) | 10 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | .60 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 231 (3.6) | 27 (3.7) | 125 (4.0) | 63 (3.7) | 10 (1.8) | 3 (1.9) | 3 (2.4) | .14 |

| Hypertension | 4381 (68.8) | 485 (66.8) | 2110 (67.6) | 1191 (70.1) | 403 (73.5) | 94 (60.3) | 98 (79.0) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 1057 (16.6) | 126 (17.4) | 542 (17.4) | 265 (15.6) | 86 (15.7) | 21 (13.5) | 17 (13.7) | .41 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3997 (62.7) | 451 (62.1) | 1985 (63.6) | 1056 (62.2) | 338 (61.7) | 86 (55.1) | 81 (65.3) | .32 |

| Hospitalized bleed | 182 (2.9) | 16 (2.2) | 87 (2.8) | 48 (2.8) | 22 (4.0) | 5 (3.2) | 4 (3.2) | .56 |

| Chronic liver disease | 285 (4.5) | 42 (5.8) | 152 (4.9) | 72 (4.2) | 12 (2.2) | 5 (3.2) | 2 (1.6) | .02 |

| Chronic lung disease | 1870 (29.3) | 236 (32.5) | 923 (29.6) | 481 (28.3) | 153 (27.9) | 36 (23.1) | 41 (33.1) | .12 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 178 (2.8) | 25 (3.4) | 88 (2.8) | 39 (2.3) | 18 (3.3) | 2 (1.3) | 6 (4.8) | .27 |

| Hypothyroidism | 816 (12.8) | 112 (15.4) | 394 (12.6) | 196 (11.5) | 66 (12.0) | 20 (12.8) | 28 (22.6) | .003 |

| Diagnosed depression | 1016 (15.9) | 120 (16.5) | 536 (17.2) | 256 (15.1) | 62 (11.3) | 28 (17.9) | 14 (11.3) | .007 |

| Diagnosed dementia | 292 (4.6) | 34 (4.7) | 134 (4.3) | 82 (4.8) | 24 (4.4) | 10 (6.4) | 8 (6.5) | .69 |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 747 (11.2) | 56 (7.7) | 269 (8.6) | 266 (15.7) | 119 (21.7) | 24 (15.4) | 13 (10.5) | <.001 |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 407 (6.4) | 48 (6.6) | 184 (5.9) | 104 (6.1) | 43 (7.8) | 17 (10.9) | 11 (8.9) | .07 |

| Baseline medication use | ||||||||

| ACE inhibitor | 1369 (21.5) | 164 (22.6) | 628 (20.1) | 381 (22.4) | 128 (23.4) | 32 (20.5) | 36 (29.0) | .07 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 619 (9.7) | 85 (11.7) | 297 ( 9.5) | 155 (9.1) | 52 (9.5) | 14 (9.0) | 16 (12.9) | .34 |

| β-Blocker | 1736 (27.2) | 206 (28.4) | 826 (26.5) | 452 (26.6) | 154 (28.1) | 50 (32.1) | 48 (38.7) | .04 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 854 (13.4) | 98 (13.5) | 405 (13.0) | 224 (13.2) | 79 (14.4) | 23 (14.7) | 25 (20.2) | .29 |

| Diuretic | 1473 (23.1) | 185 (25.5) | 691 (22.1) | 374 (22.0) | 135 (24.6) | 45 (28.8) | 43 (34.7) | .003 |

| Hydralazine | 115 (1.8) | 10 (1.4) | 59 (1.9) | 27 (1.6) | 10 (1.8) | 3 (1.9) | 6 (4.8) | .17 |

| Vasodilator | 119 (1.9) | 11 (1.5) | 62 (2.0) | 27 (1.6) | 10 (1.8) | 3 (1.9) | 6 (4.8) | .19 |

| α-Blocker | 498 (7.8) | 61 (8.4) | 241 (7.7) | 129 (7.6) | 43 (7.8) | 11 (7.1) | 13 (10.5) | .87 |

| Any antihypertensive agent | 3641 (57.1) | 450 (62.0) | 1719 (55.1) | 959 (56.5) | 332 (60.6) | 97 (62.2) | 84 (67.7) | <.001 |

| Nitrates | 163 (2.6) | 21 (2.9) | 80 (2.6) | 41 (2.4) | 14 (2.6) | 4 (2.6) | 3 (2.4) | .99 |

| Statin | 1865 (29.3) | 234 (32.2) | 923 (29.6) | 471 (27.7) | 154 (28.1) | 42 (26.9) | 41 (33.1) | .24 |

| Oral anticoagulant | 503 (7.9) | 58 (8.0) | 250 (8.0) | 126 (7.4) | 37 (6.8) | 18 (11.5) | 14 (11.3) | .27 |

| Digoxin | 150 (2.4) | 17 (2.3) | 65 (2.1) | 43 (2.5) | 17 (3.1) | 7 (4.5) | 1 (0.8) | .22 |

| Antiarrhythmic agent | 102 (1.6) | 14 (1.9) | 43 (1.4) | 28 (1.6) | 11 (2.0) | 3 (1.9) | 3 (2.4) | .75 |

| Diabetic therapy | 329 (5.2) | 53 (7.3) | 163 (5.2) | 79 (4.7) | 21 (3.8) | 8 (5.1) | 5 (4.0) | .08 |

| Vital signs | ||||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 126.6 (16.9) | 126.2 (17.6) | 126.7 (16.7) | 126.1 (17.0) | 126.9 (17.3) | 127.1 (15.5) | 129.9 (18.8) | .29 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 73.3 (11.2) | 72.7 (11.0) | 73.9 (11.1) | 73.0 (11.2) | 72.9 (11.3) | 72.5 (11.3) | 69.6 (13.0) | <.001 |

| Heart rate, mean (SD), beats/min | 75.0 (15.7) | 75.8 (16.0) | 74.9 (15.2) | 74.7 (16.1) | 74.9 (17.2) | 74.3 (16.3) | 76.1 (15.4) | .66 |

| Heart rate, median (IQR), beats/min | 73.0 (64.0-84.0) | 74.0 (64.0-85.0) | 73.0 (64.0-84.0) | 73.0 (64.0-83.0) | 73.0 (63.0-84.0) | 72.0 (64.0-84.0) | 75.0 (65.0-84.0) | .49 |

| Unknown heart rate | 208 (3.3) | 18 (2.5) | 72 (2.3) | 69 (4.1) | 33 (6.0) | 10 (6.4) | 6 (4.8) | |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)d | 28.3 (6.0) | 27.1 (6.0) | 28.3 (6.1) | 28.5 (5.7) | 28.9 (6.0) | 29.6 (6.4) | 28.5 (6.1) | <.001 |

| Laboratory results | ||||||||

| Total cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dLe | 175.2 (38.6) | 180.4 (39.7) | 175.2 (37.9) | 174.3 (39.6) | 172.2 (36.7) | 175.6 (39.5) | 173.5 (41.8) | .04 |

| Low-density lipoprotein, mean (SD), mg/dLe | 99.2 (32.6) | 101.3 (33.6) | 98.8 (31.9) | 99.2 (33.8) | 98.0 (30.8) | 100.8 (30.9) | 101.0 (37.2) | .62 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Race and ethnicity were reported for this study to reflect the diversity of the cohort and to evaluate differences in study outcomes that may be present across different racial and ethnic groups. Race and ethnicity data were collected from data available in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California electronic health record, which includes the following available categories for race: Asian, Black/African American, Multiracial, Native American/Alaska Native, Pacific Islander, White, and unknown and a choice between Hispanic and non-Hispanic ethnicity.

Other includes Native American or Alaska Native and those who reported multiple races. These groups were combined owing to small numbers in the former and the inability to reliably disaggregate data by race category in the latter.

Defined as those self-reporting that they do not smoke but are exposed to smoke through other individuals in the home.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

To convert to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259.

Figure 1. Distribution of Initial Aortic Size Among Patients With Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm (TAA).

Unadjusted rates of AD were low across the cohort, occurring in only 44 patients (0.7%) with an overall incidence of 0.22 (95% CI, 0.15-0.28) per 100 person-years, and were generally low across the spectrum of initial TAA size with an inflection point seen for patients with TAA size 6.0 cm or larger (Table 2; eFigure 2 in Supplement 1). No AD events were observed for patients with initial TAA size smaller than 4.0 cm, and rates were less than 0.5 per 100 person-years (corresponding to a risk of less than 1% per year) for those with initial TAA size less than 6.0 cm. For those with initial TAA size of 6.0 cm or larger, the rate of AD was 2.19 events per 100 person-years. Event rates for all-cause death were much higher than for confirmed AD, and rates of the composite outcome of AD or all-cause death increased monotonically with larger initial TAA size, and was notably higher for patients with TAA size 6.0 cm or larger. As expected, the rates of elective aortic surgery increased with larger initial TAA size. Overall, AD events were rare among patients with bicuspid aortic valve, with only 1 of the 44 AD events being from the 747 patients with bicuspid aortic valve. Elective surgery was more common among patients with bicuspid aortic valve (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Among the 44 AD events, the location of the maximal predissection aortic dilation was most commonly the ascending aorta (n = 27) compared to the aortic root (n = 13) or aortic arch (n = 4). Aortic dissection was the most common outcome (n = 37) of AD events, with intramural hematoma (n = 3) and aortic rupture (n = 4) being rarer. Patients with AD were generally older, with a median (IQR) age of 75.2 (63.7-81.0) years.

Table 2. Unadjusted Outcomes of Death, Aortic Dissection, and Aortic Surgery by Initial Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm (TAA) Size and Time-Updated TAA Size.

| No. (%) | Total event-free person-years, No. | Deaths, No. (%) | Aortic dissection or rupture, No. (%) | Aortic surgical procedures, No. (%) | Rate of aortic dissection per 100 person-years (95% CI)b | Rate of aortic dissection or all-cause death per 100 person-years (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes by initial TAA size, cm | |||||||

| <4.0 | 726 (11.4) | 2700 | 121 (16.7) | 0 | 38 (5.2) | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) | 4.41 (3.68-5.28) |

| 4.0-4.4 | 3120 (49.0) | 10 005 | 514 (16.5) | 15 (0.5) | 237 (7.6) | 0.15 (0.09-0.25) | 4.96 (4.54-5.42) |

| 4.5-4.9 | 1698 (26.7) | 5436 | 324 (19.1) | 18 (1.1) | 313 (18.4) | 0.33 (0.21-0.53) | 5.63 (5.04-6.30) |

| 5.0-5.4 | 548 (8.6) | 1380 | 136 (24.6) | 6 (1.1) | 225 (41.1) | 0.43 (0.20-0.97) | 8.48 (7.07-10.16) |

| 5.5-5.9 | 156 (2.5) | 334 | 40 (25.6) | 1 (0.6) | 78 (50.0) | 0.30 (0.04-2.12) | 11.06 (8.01-15.27) |

| ≥6.0 | 124 (2.0) | 182 | 47 (37.9) | 4 (3.2) | 64 (51.6) | 2.19 (0.82-5.84) | 21.36 (15.61-29.24) |

| Outcomes by time-updated TAA size, cma | |||||||

| <4.0 | NA | 3039 | 146 | 0 | 40 | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) | 4.48 (3.78-5.30) |

| 4.0-4.4 | NA | 9808 | 486 | 11 | 209 | 0.11 (0.06-0.20) | 4.79 (4.38-5.25) |

| 4.5-4.9 | NA | 5169 | 311 | 13 | 281 | 0.25 (0.15-0.43) | 5.77 (5.15-6.46) |

| 5.0-5.4 | NA | 1479 | 130 | 8 | 249 | 0.54 (0.27-1.08) | 7.78 (6.48-9.34) |

| 5.5-5.9 | NA | 348 | 47 | 4 | 97 | 1.15 (0.43-3.06) | 12.62 (9.39-16.96) |

| ≥6.0 | NA | 194 | 62 | 8 | 79 | 4.11 (2.05-8.21) | 27.21 (20.79-35.62) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Patients were classified into TAA size bins based on each new imaging study across follow-up, and outcomes of aortic dissection or death were attributed to the most recent TAA size prior to the event. The time at risk within each aortic size bin began at the date of each new imaging study and extended until the next imaging study or censoring event. Sample size not populated as patients changed categories over time. Percentages were not calculated for death, aortic dissection or rupture, or aortic surgery due to lack of relevant denominator.

Rate of aortic dissection and rate of aortic dissection or all-cause death were censored at aortic surgery for those who underwent surgery.

Using time-updated TAA size, where patients were classified into TAA size categories based on their most recent TAA imaging study, unadjusted rates of AD remained small (less than 1% per year) for those with TAA size smaller than 5.5 cm and increased in a substantially more monotonic fashion until an inflection point was again seen at 6.0 cm (Table 2). As TAA size categories increased from 4.0 to 5.5 cm, rates of AD more than doubled for each size category, reaching 1.15 per 100 person-years (corresponding to a risk of slightly more than 1% per year) for the 5.5 to 5.9 cm TAA size category. The unadjusted AD rate rose dramatically for patients with TAA size 6.0 cm or larger to greater than 4.1 per 100 person-years. For patients with AD, 48% (21 of 44) had an imaging study within 1 year prior to the event, with the median (IQR) measurement being 367 (108-706) days prior to AD.

Rates of the composite outcome of AD or all-cause death increased monotonically and were notably higher in the largest time-updated TAA size categories (ie, 5.5 cm or larger) compared to analysis by initial TAA size, with the steepest event rate increase for TAA 6.0 cm or larger. Similarly, the number of aortic surgeries within each size category skewed toward larger aortic sizes when analyzed using time-updated TAA size.

In multivariable models that controlled for competing risks, larger initial TAA size was independently associated with an increased risk of AD. In models that examined initial TAA size as the predictor of interest, the adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for risk of AD were increased for aortic size 4.5 to 4.9 cm (HR, 2.37; 95% CI, 1.17-4.81) relative to the reference group of initial TAA size 4.0 to 4.4 cm. The HRs for initial TAA size of 5.0 to 5.4 cm and 5.5 to 5.9 cm were not statistically significant (low overall event rates within these bins), but the HR increased dramatically for patients with initial TAA size 6.0 cm or larger (HR, 11.09; 95% CI, 3.05-40.36) (Table 3). However, in models that categorized TAA size as a time-updated variable, the HRs for adjusted risk of AD increased monotonically across the spectrum of TAA size, until rising dramatically for those with TAA size 6.0 cm or larger (HR, 26.03; 95% CI, 9.00-75.23). Similar patterns were noted for the composite outcome of AD and all-cause death, with a marked increase in risk for those with TAA size 6.0 cm or larger whether using initial or time-updated TAA size.

Table 3. Multivariable Association of Initial Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm (TAA) Size and Most Recent TAA Size Prior to Occurrence Clinical Outcomes.

| Outcome | Initial TAA size models | Time-updated models using most recent TAA size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Aortic dissectiona | ||||

| TAA size, cm | ||||

| <4.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 4.0-4.4 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 4.5-4.9 | 2.37 (1.17-4.81) | .02 | 2.08 (0.92-4.73) | .08 |

| 5.0-5.4 | 2.72 (0.99-7.45) | .05 | 4.74 (1.81-12.40) | .002 |

| 5.5-5.9 | 2.08 (0.26-16.67) | .49 | 10.16 (2.94-35.11) | <.001 |

| ≥6.0 | 11.09 (3.05-40.36) | <.001 | 26.03 (9.00-75.23) | <.001 |

| Aortic dissection or all-cause deathb | ||||

| TAA size, cm | ||||

| <4.0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 4.0-4.4 | 1.22 (1.00-1.50) | .048 | 1.17 (0.96-1.41) | .12 |

| 4.5-4.9 | 1.35 (1.09-1.68) | .007 | 1.29 (1.05-1.59) | .02 |

| 5.0-5.4 | 1.71 (1.31-2.22) | <.001 | 1.39 (1.07-1.79) | .01 |

| 5.5-5.9 | 1.60 (1.10-2.34) | .02 | 1.51 (1.06-2.15) | .02 |

| ≥6.0 | 2.55 (1.76-3.69) | <.001 | 3.46 (2.49-4.80) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable.

Competing risk model (vs death and aortic surgery) adjusted for baseline variables of index age, sex, race, smoking status, body mass index, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein, atrial flutter or fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, mitral or aortic valvular disease, heart failure, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, chronic lung disease, hypothyroidism, diagnosed depression, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and bicuspid aortic valve.

Competing risk model (vs aortic surgery) adjusted for baseline variables of index age, sex, race, smoking status, body mass index, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein, acute coronary syndrome, ischemic stroke, atrial flutter or fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, mitral or aortic valvular disease, heart failure, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, chronic liver disease, chronic lung disease, hypothyroidism, diagnosed depression, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and bicuspid aortic valve.

Based on multivariable model results for the risk of AD with time-updated TAA size, we found the predicted 5-year risks of AD were modest until reaching the 5.5 cm threshold, where the 5-year predicted risk of AD increased to 3.6% (95% CI, 1.8-12.8) for TAA size of 5.5 to 5.9 cm (Figure 2) (predicted risks of AD within 5 years were 0.3% [95% CI, 0.3-0.7], 0.6% [95% CI, 0.4-1.3], 1.5% [95% CI, 1.2-3.9], 3.6% [95% CI, 1.8-12.8], and 10.5% [95% CI, 2.7-44.3] in patients with initial TAA size of 4.0 to 4.4 cm, 4.5 to 4.9 cm, 5.0 to 5.4 cm, 5.5 to 5.9 cm, and 6.0 cm or larger, respectively). In addition, the predicted 5-year risks of AD were higher for patients in whom the predicted TAA size increased by 1 size category at 2 years’ follow-up. There were no meaningful differences in predictive power between models that included aortic size vs aortic size index, and overall discrimination was excellent in both sets of models (eTables 4 and 5 in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. Predicted Risk of Aortic Dissection Over 5 Years for Fixed and Increasing Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm (TAA) Size.

Estimated predicted 5-year cumulative incidence was based on fitted multivariable Cox models with time-dependent covariates, considering the case where TAA size remained constant over 5 years’ follow-up and where TAA size increased 1 category at 2 years.

Discussion

In a large integrated health care delivery system with more than 4.5 million patients in Northern California, we identified a large sociodemographically diverse cohort of adults with TAA. Aortic size at time of TAA diagnosis varied greatly, with most TAAs measuring between 4.0 and 5.0 cm but with substantial numbers of patients having aneurysms 5.0 cm or larger. While receipt of elective aortic surgery was more common in patients with larger aortic sizes, a substantial number of patients with large aneurysms did not undergo surgery during follow-up but were monitored conservatively. These findings are crucial, as clinical decision-making for patients with large aneurysms has significant implications for the patient—eg, whether to undergo major aortic surgery or not—and is currently based on information from relatively small samples of patients with large aneurysms at tertiary centers.3,4,11

We found a low absolute risk of AD in the overall TAA population, occurring in 0.7% of patients across follow-up (n = 44; overall annual incidence of 0.22 per 100 person-years). Larger aortic size was associated with higher risks of AD and all-cause death after adjustment for potential confounders and competing risks, with a significant inflection point in risk at 6.0 cm. In unadjusted analyses, risk of AD was less than 1% per year for initial TAA size 6.0 cm or larger, and in time-updated analyses that updated TAA size with subsequent imaging studies, average risk of AD remained less than 1% per year for TAA size smaller than 5.5 cm, 1.15% per year for those with aneurysms 5.5 to 5.9 cm, and significantly higher at 4.1% per year for those with aneurysms 6.0 cm or larger. Overall, these findings support the current consensus guidelines advising aortic surgery at a TAA size of 5.5 cm for most patients to allow for elective intervention before aneurysms grow beyond 6.0 cm, where the risk of AD substantially increases.

Because aortic imaging is known to be complex,25 with initial diagnosis often made from imaging studies that are not typically dedicated to measuring the thoracic aorta (ie, chest computed tomography or echocardiogram for other indications) and subsequent follow-up studies being more dedicated to aortic measurement to track and measure TAA size and growth, we used a novel analytic technique to allow for time-updated classification of aortic size. This allowed for subsequent imaging studies after initial diagnosis to be incorporated into the analysis, and to obtain more precise estimates for the association between TAA and outcomes. We feel this is a more accurate method to study TAA size, as study-to-study discrepancies in imaging are common.25 Our study represents a real-world analysis of the association between TAA size and outcomes. Further, using our time-updated framework, we were able to predict long-term (ie, 5-year) risks for patients whose aneurysms were stable and for those whose TAA increased in size by 1 size category over a 5-year period. We found no meaningful difference in the predictive power of our models when indexing aortic size by height and weight.

We studied the outcomes of AD alone, as well as the composite outcome of AD and all-cause death. Both are important patient-related outcomes, and our system may be one of the most accurate among known natural history studies at capturing all true AD outcomes. Because KPNC is a fully integrated health care delivery system where patients obtain both health insurance and comprehensive health care, we are able to capture data on every aspect of a patient’s health care journey and are not reliant on questionnaires, requests from referring doctors, or other methods which may misclassify or miss some outcomes.4,11,26 Each AD outcome was manually adjudicated through extensive review of medical records and imaging (when available). Furthermore, since patients with TAA are generally older, the competing risks of death are significant. Because autopsy rates in the US are low, determining the true cause of death for patients who do not present to the hospital is difficult if not impossible. It may be the case that those with large aneurysms experienced sudden death at home due to rupture or dissection, or that many of the deaths in this population are unrelated to TAA. In multivariable modeling, both outcomes saw a significant inflection point at 6.0 cm in both initial and time-updated size models, which supports the current recommendation for surgical intervention at 5.5 cm before TAAs progress to larger sizes.

The finding of a low risk of AD is consistent with and similar in magnitude to the most recent estimates3 of AD for TAA size up to 5.5 cm. However, compared with Kim et al,3 the cohort in our study was larger, with substantially more patients with larger aneurysms, including those with TAA size 5.5 cm or larger, allowing for risk estimates beyond the spectrum of moderately dilated aortas. Our data are complementary in that we corroborate a low risk of dissection at moderate aortic sizes, but confirm an inflection point in risk at 6.0 cm to further validate the 5.5-cm operative threshold in current consensus guidelines. Conversely, our estimates of the risk of AD at each size threshold are much lower than earlier reports.4,11 Ours is a more contemporary cohort, and improved blood pressure control or other secular trends in cardiovascular risk factor management might at least partially explain differential rates in aortic outcomes. One of the limitations of prior studies from tertiary referral centers is the lack of population-based estimates of risk. Our study is a close approximation of population-based estimates of risk, as the study cohort was drawn from a TAA patient safety net system within a closed health care system of more than 4 500 000 persons. While not 100% of patients identified with TAA may have been included in our study (eg, some patients with a TAA identified on imaging studies may not have had a diagnosis placed in the record or have been referred to the regional TAA surveillance program), ours may be the closest to true population-based risk estimates to date.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, aortic size measurements were based on a combination of radiologist reporting (computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging), cardiology reporting (echocardiography), and overreading by cardiovascular surgeons with likely interreader variability.25 However, we used novel time-updated modeling techniques to include follow-up imaging measurements in the analysis, which are generally more accurate for aortic measurement as those studies are typically dedicated to following the TAA. In addition, we prioritized the overread measurements by cardiovascular surgeons involved in the aortic surveillance program, and our study represents a real-world analysis of the association between aortic size measurement and outcomes, although our findings reflect the results of modeling techniques and not prospective imaging protocols. Second, receipt of aortic surgery was based on date of first relevant diagnosis (ICD-9/10-CM) or procedure code (CPT), with potential for misclassification although unlikely. Third, we could not ascertain the cause of death to separate aortic vs nonaortic deaths. Because autopsy remains rare, determining cause of death remains challenging in all such natural history studies. Fourth, as in all aortic natural history studies, many patients were removed from the risk pool with prophylactic aortic surgery, but ours is one of the largest cohorts to follow patients with large aortic sizes who did not undergo surgery. Fifth, blood pressure control in our cohort is better than in most systems,27 which may affect generalizability. Additionally, we could not account for aortic regurgitation in our analysis, as these data are not uniformly available across the cohort.

Conclusions

We identified a large sociodemographically diverse cohort of more than 6300 nonsyndromic adults with TAA, which included substantial follow-up with patients with all TAA sizes, including large aortic sizes that have been previously understudied. Larger aortic size was associated with higher risk of AD and all-cause death after adjustment for potential confounders and competing risks, but absolute risk of AD was low in the overall cohort with an inflection point at 6.0 cm, supporting current guidelines recommending surgery at 5.5 cm. Earlier prophylactic surgery should be considered selectively in nonsyndromic patients with TAA, given the nontrivial risks associated with aortic surgery.

eTable 1. ICD-9 And ICD-10 Codes Used To Identify Syndromic Patients For Exclusion

eMethods

eFigure 1. Cohort Assembly

eTable 2. Additional Baseline Characteristics for Patients with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm

eFigure2. Cumulative Incidence of Aortic Dissection, All-Cause Mortality, and Elective Aortic Surgery, by Initial TAA size

eTable 3. Surgery among bicuspid aortic valve patients

eTable 4. Model Discrimination Parameters (C-statistics) for Models Using Aortic Size vs Aortic Size Index

eTable 5. Multivariable Association of Initial Aortic Size Index (ASI) and Most Recent ASI Prior to Outcome with Clinical Outcomes

The Kaiser Permanente Northern California Center for Thoracic Aortic Disease collaborators

References

- 1.Coady MA, Rizzo JA, Hammond GL, et al. What is the appropriate size criterion for resection of thoracic aortic aneurysms? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113(3):476-491. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70360-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coady MA, Rizzo JA, Goldstein LJ, Elefteriades JA. Natural history, pathogenesis, and etiology of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Cardiol Clin. 1999;17(4):615-635. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8651(05)70105-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JB, Spotnitz M, Lindsay ME, MacGillivray TE, Isselbacher EM, Sundt TM III. Risk of aortic dissection in the moderately dilated ascending aorta. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(11):1209-1219. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies RR, Gallo A, Coady MA, et al. Novel measurement of relative aortic size predicts rupture of thoracic aortic aneurysms. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(1):169-177. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pape LA, Awais M, Woznicki EM, et al. Presentation, diagnosis, and outcomes of acute aortic dissection: 17-year trends from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(4):350-358. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283(7):897-903. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.7.897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang W, Duan W, Xue Y, et al. ; Registry of Aortic Dissection in China Sino-RAD Investigators . Clinical features of acute aortic dissection from the Registry of Aortic Dissection in China. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148(6):2995-3000. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mansour AM, Peterss S, Zafar MA, et al. Prevention of aortic dissection suggests a diameter shift to a lower aortic size threshold for intervention. Cardiology. 2018;139(3):139-146. doi: 10.1159/000481930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pape LA, Tsai TT, Isselbacher EM, et al. ; International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Investigators . Aortic diameter >or = 5.5 cm is not a good predictor of type A aortic dissection: observations from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Circulation. 2007;116(10):1120-1127. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.702720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundt TM. Aortic replacement in the setting of bicuspid aortic valve: how big? how much? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149(2)(suppl):S6-S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies RR, Goldstein LJ, Coady MA, et al. Yearly rupture or dissection rates for thoracic aortic aneurysms: simple prediction based on size. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(1):17-27. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)03236-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zafar MA, Li Y, Rizzo JA, et al. Height alone, rather than body surface area, suffices for risk estimation in ascending aortic aneurysm. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155(5):1938-1950. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.10.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. ; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease); Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists . ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(3):e1-e148. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; American College of Radiology; American Stroke Association; Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Interventional Radiology; Society of Thoracic Surgeons; Society for Vascular Medicine . 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(14):e27-e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiratzka LF, Creager MA, Isselbacher EM, et al. Surgery for aortic dilatation in patients with bicuspid aortic valves: a statement of clarification from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(6):724-731. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon N, Lin T. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California adult member health survey. Perm J. 2016;20(4):15-225. doi: 10.7812/TPP/15-225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296-1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Go AS, Lee WY, Yang J, Lo JC, Gurwitz JH. Statin therapy and risks for death and hospitalization in chronic heart failure. JAMA. 2006;296(17):2105-2111. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Go AS, Yang J, Ackerson LM, et al. Hemoglobin level, chronic kidney disease, and the risks of death and hospitalization in adults with chronic heart failure: the Anemia in Chronic Heart Failure: Outcomes and Resource Utilization (ANCHOR) study. Circulation. 2006;113(23):2713-2723. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.577577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. ; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) . A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604-612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, Sorel M, Selby JV, Go AS. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(23):2155-2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomon MDTG, Tabada G, Allen A, Sung SH, Go AS. Large-scale identification of aortic stenosis and its severity using natural language processing on electronic health records. Cardiovasc Digit Health J. 2021;2(3):156-163. doi: 10.1016/j.cvdhj.2021.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fine JPGR. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanche P, Dartigues JF, Jacqmin-Gadda H. Estimating and comparing time-dependent areas under receiver operating characteristic curves for censored event times with competing risks. Stat Med. 2013;32(30):5381-5397. doi: 10.1002/sim.5958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elefteriades JA, Mukherjee SK, Mojibian H. Discrepancies in measurement of the thoracic aorta: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(2):201-217. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu J, Zafar MA, Li Y, et al. Ascending aortic length and risk of aortic adverse events: the neglected dimension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(15):1883-1894. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaffe MG, Lee GA, Young JD, Sidney S, Go AS. Improved blood pressure control associated with a large-scale hypertension program. JAMA. 2013;310(7):699-705. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.108769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. ICD-9 And ICD-10 Codes Used To Identify Syndromic Patients For Exclusion

eMethods

eFigure 1. Cohort Assembly

eTable 2. Additional Baseline Characteristics for Patients with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm

eFigure2. Cumulative Incidence of Aortic Dissection, All-Cause Mortality, and Elective Aortic Surgery, by Initial TAA size

eTable 3. Surgery among bicuspid aortic valve patients

eTable 4. Model Discrimination Parameters (C-statistics) for Models Using Aortic Size vs Aortic Size Index

eTable 5. Multivariable Association of Initial Aortic Size Index (ASI) and Most Recent ASI Prior to Outcome with Clinical Outcomes

The Kaiser Permanente Northern California Center for Thoracic Aortic Disease collaborators