Abstract

In the present work, gold (Au), silver (Ag), and copper (Cu) based mono- and bimetallic NPs are prepared using a cost-effective facile wet chemical route. The pH for the synthesis is optimized in accordance with the optical spectra and supported by the finite difference time domain simulation studies. FESEM and TEM micrographs are used to analyze the morphology of the prepared nanoparticles. TEM images of bimetallic nanoparticles (BMPs) verified their bimetallic nature. XRD studies confirmed the formation of fcc-structured mono- and bimetallic NPs. Photoluminescence studies of the as-synthesized NPs are in good agreement with the previous publications. These synthesized NPs showed enhanced catalytic activity for the reduction/degradation of 4-nitrophenol, rhodamine B, and indigo carmine dyes in the presence of sodium borohydride (NaBH4) compared to NaBH4 alone. For the reduction of 4-nitrophenol, Au, Cu, and CuAg nanoparticles exhibited good catalytic efficiency compared to others, whereas for the degradation of rhodamine B and indigo carmine dyes the catalytic efficiency is comparatively high for CuAg BMPs. Furthermore, the antibacterial assay is carried out, and Ag NPs display effective antibacterial activity against Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, Acinetobacter baumannii, Shigella flexneri, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Introduction

Tailoring the structural and materialistic properties of nanoparticles (NPs) has transfigured areas such as sensing,1 drug delivery, and antimicrobial applications,2,3 nanoelectronics,4 catalysis,5 etc. Bimetallic nanoparticles (BMPs) opened new frontiers exhibiting properties superior to those of their mono-counterparts owing to the synergistic effect.6 Integrating the transition elements with the noble metals rationally enhances their performance, making them cost-effective and user-friendly from an application point of view. The electrical and optical characteristics are sensitive to the size, shape, and composition of the BMPs and uplift the stability and diffusion by tuning the plasmonic band through an additional degree of freedom.7,8 Electrochemistry coalesced with the surface plasmon band energy of BMPs has revolutionized the catalytic performance and sensing mechanism9,10 of electronic devices.

In recent times, BMPs are also used for the regeneration of noble metals from industrial and electronic waste, signifying their invaluable role in modern applications.11 In addition, they are potential candidates that are widely researched for antibacterial activity12 and other targeted applications.13−22 Their industrial applications are extended in water purification and splitting, textiles, pesticides and drugs, and electrocatalysis where some processes currently use hazardous chemicals or carcinogenic dyes such as rhodamine B, indigo carmine, methyl blue, Congo red, etc., causing serious concerns to the environment.23−26 These untreated effluents may lead to adverse impacts on aquatic life by causing eutrophication, under-oxygenation, color, turbidity, and odor. Thus, nanoparticles for catalytic and antimicrobial studies play a pivotal role in this active area of research.5 Therefore, we have prepared Au, Ag, Cu, and their BMPs via chemical reduction due to its feasibility, affordability, and reliability over other methods to investigate their catalytic reduction, dye degradation,27−29 and antibacterial properties.30−33

Au, Ag, Cu, and their alloys at the nano realms are much acclaimed for their strong localized surface plasmonic resonance (LSPR) response to the electromagnetic (EM) fields compared with their catalytic and antimicrobial nature.34−39 Many types of nano-photocatalysts exhibit enhanced performance owing to their surface area by dovetailing homo- and heterogeneous catalytic properties and are employable for wastewater treatment.40 In addition to these applications, the ability to manipulate incident optical energy into radiative transfers through controlled and tunable LSPR coupling defies the efficacy of quantum efficiency (QE) and is also influenced by structural, quantum size, and electronic effects.5,41−44 With a combination of noble and weak plasmonic BMPs we can enhance the QE of the system as a result of narrowed plasmonic bandwidth. This allows us to build photoresponsive structures with complex optical permittivity45 with which the LSPR induced charge separation at the metallic interface without energy loss under illumination can be realized.46

In this work, the proposed mono- and BMPs are employed for checking the performance of catalytic reduction/degradation of 4-nitrophenol, rhodamine B, and indigo carmine dyes. Later, the invitro antibacterial activity of Gram-positive bacteria such as Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Enterococcus faecium as well as Gram-negative bacteria such as Vibrio cholerae, Escherichia coli, Aeromonas hydrophila, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, Acinetobacter baumannii, Shigella flexneri, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are analyzed and results are discussed in detail. Three-dimensional finite difference time-domain (FDTD)47 simulations are carried out to support the LSPR-apprehended response of incident optical energy by considering their individual and compositional dielectric permittivity along with the size parameters. The pH of the synthesis procedure is tuned for investigating the morphological and structurally dependent optical spectra and photoluminescent properties.

Results and Discussion

Metal NPs are exhibit efficient UV–vis absorbance spectra compared to the semiconducting materials due to their readily available conduction electrons, which facilitate LSPR at respective wavelengths. Enhanced light–matter interaction influenced by structural, compositional, and surrounding mediums make them potential photocatalysts.48−50Figure 1a–e explicates the pH-dependent optical absorption spectra of Au, Ag, Cu, AuAg, and CuAg NPs in which we can realize that the pH is tuned to control the NP shape- and size-based LSPR spectral position, intensity, and corresponding peak broadening. The resonance peak (λmax) of the as prepared mono- and BMPs matches well with the reported values.51−55 Au NPs have a sharp intense peak for pH 2, while the Ag, Cu, AuAg, and CuAg have optimized λmax at pH values 10, 7, 4, and 11.5, respectively. Thus, the pH not only governs the peak intensity but also its broadening and a shift in λmax can also be realized. In the case of Au NPs, the peak intensity diminished while broadening and red shifting also occur with an increase in pH, which could be attributed to the possible agglomeration of NPs at higher pH values. For Ag NPs, peak intensity has increased from pH 8–10 and then decreased upon further increasing the pH. In the case of Cu NPs, no peaks are obtained for lower pH until 7. This is because at lower pH larger Cu NPs with a nonuniform size distribution are expected due to aggregation, but there’s also a chance that no reaction will occur owing to the lack of electrons.56 For BMPs, peak intensity increased from pH 2 to 4 and then decreased, signifying the peak broadening for AuAg. For the CuAg, a sharp peak appearing at pH 11.5 and broader peak at pH 12 indicate the sensitive nature of the pH with LSPR. The pH values other than the observed sharp peaks are not able to give a proper peak intensity due to the agglomeration of NPs. The mechanism behind the pH dependency on the spectral changes is explained in the Supporting Information.

Figure 1.

Optical absorption spectra of (a) Au, (b) Ag, (c) Cu, (d) AuAg, and (e) CuAg NPs as a function of pH.

To confirm the experimental findings, FDTD simulation studies have been carried out and are explicated in Figure S1. The NPs dispersed in water medium are illuminated by the plane wave source under symmetry boundary conditions (BCs). Ideally, the NPs are considered as periodic, and the periodicity (P) is varied relative to the size of the NP to leverage with the experimental yields. The optical constants FDTD of the monometallic NPs are considered from the in-built material base.57,58 For the AuAg59 and CuAg BMPs, the compositional effect is induced based on Figures S2a,b and S3a,b, respectively, by approximating the individual metallic percentages. Figure S4 demonstrates the comparison of the experimental and simulated absorbance spectra where the λmax are in agreement with each other. Table S1 displays the FDTD simulation parameters incorporated for the corresponding materials. It can be realized that the effect of structural and morphological aspects on λmax are quite impactful and highly sensitive. Figures S5, S6, and S7a–e emphasize the electric field intensity, power absorption, and current density profiles at λmax, illustrating the LSPR effect of the synthesized NPs, which also attests to their suitability for catalytic and antibacterial applications.

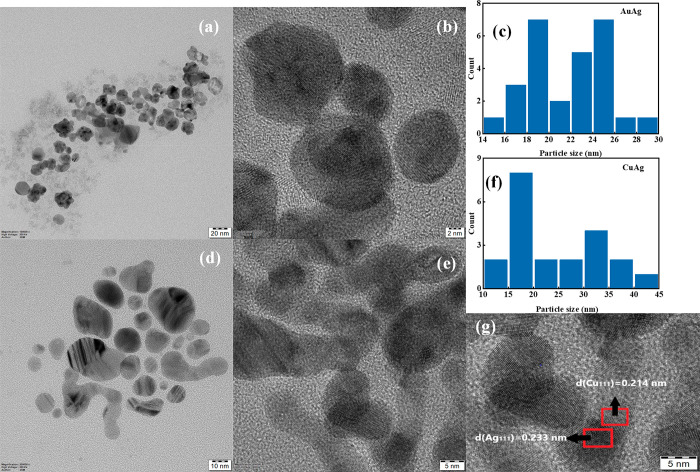

Figure 2a–e depicts the structural and morphological characterization obtained from FESEM of the respective mono- and BMPs for the optimized pH values mentioned in Figure 1. Almost all NPs are spherical in shape except for a slight variation for CuAg BMPs, which is further apprehended from the FDTD simulation studies elucidated in Figure S4e. The measured average sizes (diameter) of the synthesized Au, Ag, Cu, AuAg, and CuAg NPs for the corresponding pH are ∼15, 60, 65, 20, and 40 nm, respectively. The presence of both Au (∼18%) and Ag (∼82%) in AuAg BMPs is confirmed from the EDAX mapping (Figure S2a). Similarly, Figure S2b corroborates the existence of both Cu (∼28%) and Ag (∼72%). From the TEM micrographs (Figure 3), the bimetallic nature of prepared nanoparticles (AuAg and CuAg) is confirmed. Due to the identical lattice parameters of Au and Ag NPs, the differentiation of these two entities is quite difficult, yet because of the higher electron density of Au than Ag atoms, the presence of Au and Ag can be clearly differentiated. The EDAX spectra validate the presence of the corresponding monometallic counterparts in both AuAg and CuAg BMPs. The AuAg BMPs are almost spherical with sizes ranging from 15 to 30 nm with a mean size of 23 nm, whereas CuAg BMPs have deformed morphology with sizes ranging from 10 to 45 nm with a mean size of 24 nm. The fast Fourier transform is carried out to calculate the d-spacing of CuAg BMPs (Figure 3g) and is calculated to be 0.214 and 0.233 nm corresponding to the (111) planes of Cu and Ag NPs, which is in good agreement with lattice spacing calculated from XRD of monometallic Cu and Ag NPs, again confirming the formation of BMPs. The EDAX spectra (Figure S3a) verify the presence of both Au and Ag in AuAg BMPs with a ratio of atomic percentage ∼24:76, whereas the presence of Cu and Ag is confirmed from Figure S3b with a ratio ∼30:70. These values match well with the ratio obtained from the EDAX spectra of the FESEM analysis.

Figure 2.

FESEM images of (a) Au, (b) Ag, (c) Cu, (d) AuAg, and (e) CuAg NPs.

Figure 3.

TEM images of (a) AuAg and (d) CuAg, respectively. TEM images of (b) AuAg and (e) CuAg with high resolution. Particle size distribution histogram of (c) AuAg and (f) CuAg BMPs. (g) High-resolution TEM image of CuAg BMP with interplanar spacings corresponding to Cu(111) and Ag(111) planes.

Figure 4a–e details the crystallinity of synthesized NPs with regard to the particle size from the width of the diffraction peaks measured by XRD. To record the diffraction pattern, colloidal NPs were drop cast as thin films onto glass substrates and dried at ∼80 °C. The diffraction peaks of Au NPs at 38.06°, 44.08°, 64.36°, and 77.28° corresponded to the crystal planes (111), (200), (220), and (311), confirming the formation of face-centered cubic (fcc) structured Au NPs.60 The presence of certain unassigned peaks might be occurring due to the reducing or capping agent remnants.61 Similarly, XRD peaks of Ag and Cu NPs shown in Figure 4b,c are in agreement with the reported literature values.62,63 Since Au and Ag have similar lattice constants (0.408 and 0.409 nm), their peak positions are overlapped, and a single peak was observed at every lattice plane for AuAg BMPs (Figure 4e). The formation of Ag-rich CuAg BMPs is affirmed by optical spectra and EDAX, which can also be confirmed by XRD. The most intense peak of Cu NPs (111) appears at 43.83°. Due to the lower concentration of Cu compared to Ag, this peak merges with another peak at 44.24° corresponding to the Ag (200) plane, which makes it unnoticeable. However, by using Fityk software, the single peak is deconvoluted and yielded two of the aforementioned peaks (Figure S8), which clearly shows the presence of Cu in a lower concentration. The results are in agreement with the HRTEM results (Figure 3g). In addition, a small peak around ∼36.26° indicates the presence of the Cu2O (111) phase, which appears due to the poor chemical stability of Cu.

Figure 4.

XRD data of the (a) Au, (b) Ag, (c) Cu, (d) CuAg, and (e) AuAg NPs. The peak represented as * is due to the formed Cu2O because of ambient oxidation.

Metal NPs exhibit photoluminescence (PL) due to the radiative recombination of photoexcited holes and conduction band electrons.64 The size and shape of the metal NPs have a great impact on the LSPR position and in turn on the intensity of PL spectra.65 A strong emission band was observed at wavelengths of 531, 425, and 573 nm for excitation wavelengths of 450, 380, and 480 nm for Au, Ag, and Cu NPs, respectively (Figure 5a–c). These values match well with reported values in the literature.64,66 Furthermore, AuAg and CuAg BMPs showed emission bands at wavelengths of 574 and 577 nm for an excitation wavelength of 300 nm (Figure 5d,e). Moreover, the appearance of a single emission band also confirms the formation of BMPs or else the physical mixing of their monometallic counter parts might yield two separate peaks.67,68 The current density profiles in Figure S7 adhering to the absorbed incident power (Figure S6) by the NPs corroborates the PL properties for their application in electrochemical-based applications. The proportional relation between current density and PL properties is interrelated to the structural and morphological aspects of the particles, which can be ascribed to the LSPR peak position.69

Figure 5.

PL spectra of (a) Au, (b) Ag, (c) Cu, (d) AuAg, and (e) CuAg NPs.

Catalytic activity of the as prepared NPs is studied by carrying out catalytic reduction/degradation of various organic dyes like 4-nitrophenol, rhodamine B, and indigo carmine. The progress of catalytic reaction was continuously monitored using a spectrophotometer. According to the structural effects, the metal NPs are considered as good catalytic materials.68 Highly monodispersed colloidal metal NPs as a function of pH (see Figure 1) exhibit higher catalytic efficiency compared to the NPs prepared at other pH values. Figure 6a–e represents the absorption spectra of 4-nitrophenol in the presence of NaBH4 and Au, Ag, Cu, AuAg, and CuAg NPs, respectively. The peak at 400 nm corresponds to the nitrophenolate ion whose intensity decreases with time as the reaction continues. A small peak at 300 nm is attributed to the 4-aminophenol. The decrease in intensity of the peak at 400 nm clearly shows that the metal NPs efficiently catalyzed the conversion of hazardous 4-nitrophenol into less toxic 4-aminophenol. The color change from yellow to colorless (inset of Figure 6f) is the indication of completion of the reaction. The dye degradation efficiency of thus-prepared Au and Ag NPs is higher than that of the reported values in the literature (Table 1). Similarly, the degradation of dyes like rhodamine B and indigo carmine and their performances were evaluated (Figure. S9, S10).

Figure 6.

Absorption spectra of 4-nitrophenol in the presence of NaBH4 and (a) Au, (b) Ag, (c) Cu, (d) AuAg, (e) CuAg, and (f) without NPs, with respect to time. Optical image of 4-nitrophenol before and after catalytic degradation (inset).

Table 1. Reaction Conditions, Percentage of Degradation, Time Consumed, and Rate Constant for the Degradation of Dyes for Various Mono- and Bimetallic Nanoparticles and Comparison of a Few Reports.

| Dye | Metal NPs | Volume of colloidal NPs (μL) | Volume of NaBH4 in μL (concentration in M) | Rate constant (sec–1) | Time (min) | Degradation (%) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4- nitrophenol (0.01 M) | Au | 20 | 200 (0.5) | 0.0115 | 9 | 99.87 | present work |

| Ag | 20 | 200 (0.5) | 0.0017 | 18 | 96.34 | ||

| Cu | 20 | 200 (0.5) | 0.026 | 9 | 99.32 | ||

| AuAg | 20 | 200 (0.5) | 0.0046 | 12 | 97.17 | ||

| CuAg | 20 | 200 (0.5) | 0.0058 | 9 | 95.24 | ||

| Without catalyst | NIL | 200 (0.5) | 0.0002 | 20 | 20 | ||

| rhodamine B (0.1 μM) | Au | 100 | 20 (0.05) | 0.0058 | 6 | 87.25 | |

| Ag | 100 | 20 (0.05) | 0.0005 | 21 | 53.64 | ||

| Cu | 100 | 20 (0.05) | 0.0032 | 14 | 92.44 | ||

| AuAg | 100 | 20 (0.05) | 0.0067 | 6 | 91.20 | ||

| CuAg | 100 | 20 (0.05) | 0.0317 | 3 | 97 | ||

| Without catalyst | NIL | 20 (0.05) | 0.00003 | 20 | 4.64 | ||

| indigo carmine (0.4 μM) | Au | 100 | 20 (0.05) | 0.0147 | 4 | 97.08 | |

| Ag | 100 | 20 (0.05) | 0.0157 | 3 | 94.89 | ||

| Cu | 100 | 20 (0.05) | 0.0102 | 3 | 84.66 | ||

| AuAg | 100 | 20 (0.05) | 0.0055 | 6 | 88.59 | ||

| CuAg | 100 | 20 (0.05) | 0.0212 | 1 | 72.04 | ||

| Without catalyst | NIL | 20 (0.05) | 0.0006 | 20 | 51.38 | ||

| 4- nitrophenol | Ag | 30 | 0.02 N | 0.0029 | 22 | (68) | |

| 4- nitrophenol | Au | 200 | 500 (0.4) | 0.006 | 14 | (29) | |

| 4- nitrophenol | Au–Ag | 200 | 500 (0.4) | 0.0103 | 5 | ||

| 4- nitrophenol | Ag | 20 | 580 (0.05) | 0.0024 | 15 | 88.08 | (73) |

| rhodamine B | Cu | 100 | 20 (0.1) | 0.0027 | (74) | ||

| rhodamine B | Au | 50 | 500 (0.1) | 0.1098 | 0.33 | (75) |

Mechanism of Catalytic Degradation of Dyes

Catalytic reduction of dyes using NaBH4 as a reducing agent follows the Langmuir–Hinshelwood model. According to this model, initially the dye, as well as the reductant molecules, get adsorbed on the surface of the metallic nanocatalysts. NaBH4 molecules ionize into their respective ions (Na+ and BH4–) and are adsorbed on the surface of the catalyst. BH4– acts as an electron donor and each ion donates a single electron, which further helps in reducing the dye molecule.70 The degradation efficiency (D) of the dyes by metal NPs can be calculated using eq 1(71)

| 1 |

where C0 is the initial concentration of the dye, and Ct is the concentration of the dye at time t. Since the concentration is directly proportional to the absorbance (A), the percentage of degradation can be easily calculated using the UV–vis spectrum. The decrease in absorbance of samples at λmax (400 nm for 4-nitrophenol) at various time intervals indicates the rate of decolorization and in turn the degradation efficiency of metal NPs. Furthermore, the rate of the dye degradation was measured at a given time (t) using eq 2. The catalytic reaction follows pseudo first order kinetics, and the rate constant of the reaction (k) was calculated using ln (A0/At) vs time plot.72

| 2 |

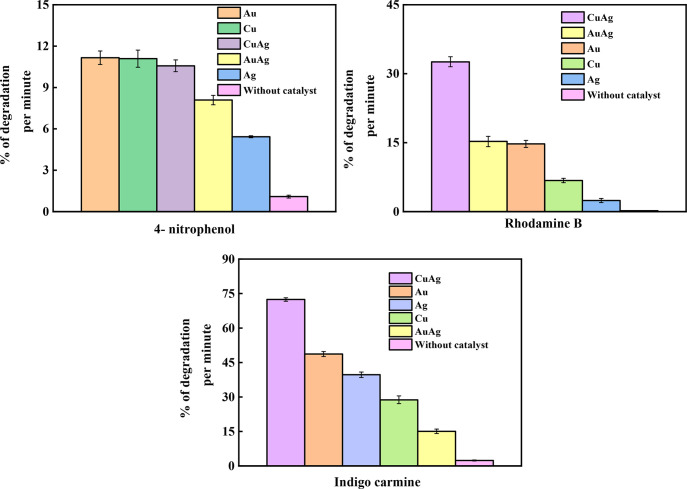

From Figure S11a–e, the rate constant of the catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol is calculated to be 0.0115, 0.0017, 0.026, 0.0046, and 0.0058 s–1 for Au, Ag, Cu, AuAg, and CuAg NPs, respectively. The degradation efficiency of different mono- and BMPs for various organic dyes is summarized in Table 1 (also see Figures 7, S12, and S13). It is observed that Au and Cu nanoparticles show ∼99.9% and 99.3% dye degradation efficiency in just 9 min for 4-nitrophenol. The catalytic activity of samples was investigated without NPs as a control. The reaction is insignificantly slow, and the percentage of conversion is only 20% in 20 min.

Figure 7.

Dye degradation (%/min) in the presence of as-synthesized nanoparticles.

Antibacterial Activity

It is well-known that the metal and semiconductor NPs are more commonly employed in antibacterial studies. In order to test the efficiency of the prepared NPs, various bacteria like P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, etc. were considered. In the present work, the Agar diffusion method is used for checking the antibacterial activity due to its simplicity, affordability, ability to test large number of microorganisms and antimicrobial agents and easy interpretation of results, etc.76 The effect of antibiotics on microorganisms can be studied qualitatively by measuring the diameter of the zone of inhibition. If the zone of inhibition is absent or less than the standard, then the bacteria is said to be resistant toward a specific antibiotic, and if it is greater than or equal to the standard, then it is considered to be sensitive as per CLSI guidelines.

Ample studies are available on the antimicrobial activity of nanomaterials. Usually, nanomaterials show antibacterial activity against Gram-negative bacteria, whereas Gram-positive bacteria are more resistant to nanomaterial-based antibacterial mechanisms. This is because in the case of Gram-positive bacteria, the outer peptidoglycan layer (80 nm) is much thicker than that for Gram-negative bacteria (8 nm). Gram-negative bacteria have peptidoglycan layer with lower thickness through which the released ions from NPs can easily reach the nuclear content of bacteria. Interestingly in the present study, Ag NPs suppressed the growth of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, the negatively charged cell wall of both Gram- positive and Gram-negative bacteria has a higher affinity toward ions released from metal NPs. In addition, the electronegativity of the cell wall is also affected by the broth used to grow the bacteria.77 All of the prepared mono- and BMPs are tested for antibacterial activity. Among these, only Ag NPs showed antibacterial activity against K. pneumoniae, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, A. baumannii, S. flexneri, P. aeruginosa, MRSA, and E. faecium with maximum inhibitory activity toward P. aeruginosa demonstrated in Figure 8. Besides, the shape of the nanomaterials plays a prominent role in their antibacterial activity. Figures 8a, S14, and S15 are the optical illustrations of the zone of inhibition for the Au, Ag, and Cu NPs for various microorganisms. The diameters of the inhibition zones are given in Table S2. Figure 8b shows a bar chart of the diameter of the inhibition zones for Ag NPs.

Figure 8.

(a) Mueller–Hinton Agar well diffusion method for evaluating antibacterial activity of Au, Ag, and Cu NPs against P. aeruginosa. (b) Bar chart of the inhibition zone for Ag nanoparticles.

The activity of these NPs was studied against diarrheal pathogens like Salmonella sp. and Shigella sp. P. aeruginosa is a very important culprit in hospitals, causing nosocomial infections. These strains of Pseudomonas are multidrug-resistant too. The sensitivity of these nanoparticles can be effectively used against such drug-resistant organisms. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus is an organism that causes infections in different parts of the body and is resistant to commonly used antibiotics. This organism is a big threat in hospitals and called as asuperbug. The activity of the NP against this clinically important organism can lead to improvements in the treatment of such multidrug-resistant organisms.

Conclusions

A simple and cost-affordable chemical reduction method is employed for the synthesis of Au-, Ag-, and Cu-based mono- and BMPs. Optical characterizations are carried out using UV–vis spectroscopy, and the characteristic LSPR peaks are observed at wavelengths of 524, 425, 583, 420, and 396 nm for Au, Ag, Cu, AuAg, and CuAg, respectively, that are being validated by FDTD simulation studies and electric field intensity, power absorption, and current density profiles. The optimum pH for the synthesis is found to be pH 2, 10, 7, 4, and 11.5 for Au, Ag, Cu, AuAg, and CuAg, correspondingly. FESEM and TEM analysis are used to understand the morphology of the prepared nanoparticles. TEM images of BMPs confirmed their bimetallic nature. XRD studies confirmed the formation of fcc-structured mono- and BMPs. Photoluminescence studies of the as-synthesized NPs are in good agreement with the previous publications. The catalytic application of these NPs is studied extensively by reducing 4-nitrophenol, rhodamine B, and indigo carmine dyes in the presence of NaBH4. Both mono- and BMPs showed excellent catalytic efficiency when compared to NaBH4 alone, among which CuAg BMPs showed comparatively higher efficiency for the degradation of all the three dyes. Ag NPs demonstrated potent antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, A. baumannii, S. flexneri, MRSA, and E. faecium with zones of inhibitions ranging from 7 to 12 mm, indicating that further research is required to consider this as an alternative therapy. The admirable catalytic efficiency of the CuAg BMPs make them one of the worthwhile alternatives for Au NPs, which can be used in wastewater treatment with certain modifications.

Materials and Methods

Copper sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4·5H2O, 99%), polyethylene glycol (PEG), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98%), hydrochloric acid, silver nitrate (AgNO3, 99%), trisodium citrate (99%), 4-nitrophenol, rhodamine B, and indigo carmine (98%) are procured from Loba Chemie Pvt, Ltd. Ascorbic acid (99%) and sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 98%) are purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Tetrachloroauric acid (HAuCl4,) is procured from Spectrochem Pvt. Ltd. All of the chemicals are used without any further purification.

Synthesis

Au NPs

Two milliliters of trisodium citrate (38 mM) is added dropwise to 10 mL of aqueous solution of HAuCl4 (1 mM) under magnetic stirring. Heating is continued until the color changes from yellow to wine red, which indicates the formation of Au NPs. Stirring is continued further for 5 min for the completion of the reaction. Here, trisodium citrate acts as both reducing and capping agent.

Ag NPs

Ten milliliters of aqueous solution AgNO3(4 mM) is heated under magnetic stirring, followed by the addition of 2 mL of trisodium citrate (19 mM) dropwise. Heating is continued until the colorless reaction mixture turns pale yellow, indicating the formation of Ag NPs. Stirring is continued further until the colloidal solution cools. Similar to Au NPs, trisodium citrate takes the role of a reducing as well as a capping agent.

Cu NPs

For the synthesis of Cu NPs, 12 mL of aqueous solution of CuSO4·5H2O (10 mM) is taken, and its pH is adjusted by adding a few drops of NaOH (100 mM). Aqueous solutions of 7 mL of PEG (20 mM) and 6 mL of ascorbic acid (20 mM) are added under constant stirring. After 1 h, an aqueous solution of 0.5 mL of NaBH4 (100 mM) is added dropwise until the appearance of a black or reddish brown color, which indicates the formation of Cu NPs. Here, ascorbic acid and NaBH4 act as the antioxidant and reducing agent, respectively, whereas polyethylene glycol acts as a surfactant.

AuAg BMPs

Bimetallic AuAg NPs are prepared using seed-assisted synthesis. For the synthesis of Au seed solution, 10 mL of aqueous solution of HAuCl4(1 mM) is heated to boiling under magnetic stirring. Two milliliters of reducing agent, i.e., trisodium citrate (38.8 mM), is added dropwise. Heating is continued until the color changes from yellow to wine red, which indicates the formation of Au nanoparticles. Stirring is continued further for 5 min until the completion of the reaction. After cooling to room temperature, 2.5 mL of seed solution is added to 8 mL of distilled water followed by the addition of 1 mL of trisodium citrate solution under magnetic stirring at room temperature. After 10 min, 1.2 mL of AgNO3 (10 mM) and 0.4 mL of ascorbic acid (100 mM) are added. Stirring is continued for 30 min.

CuAg BMPs

A seed solution method is used for the synthesis of CuAg BMPs. For the synthesis of Cu NPs, 12 mL of aqueous solution of CuSO4·5H2O (10 mM) is taken, and its pH is adjusted by adding a few drops of NaOH (100 mM). Aqueous solutions of 7 mL of PEG (20 mM) and 6 mL of ascorbic acid (20 mM) are added under constant stirring. After 1 h, an aqueous solution of 0.5 mL of NaBH4 (100 mM) and 8 mL of AgNO3 (10 mM) are added dropwise until the color changes to black, which indicates the formation of CuAg BMPs.

The effect of pH on the NPs is studied by varying the pH with the addition of 100 mM NaOH and 100 mM HCl during synthesis.

Characterization

Instruments

Optical studies were carried out using a SHIMADZU-1800 UV–vis spectrophotometer. Morphological and elemental analysis was carried out using a field emission scanning electron microscope and an energy dispersive X-ray diffraction analyzer (FESEM; Carl Zeiss; EVO-18). An X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku Miniflex 600) was used for structural analysis. Photoluminescence studies were carried out using a photoluminescence spectrometer (Jasco spectrofluorometer FP 8500).

Catalytic Studies

A 40 μL sample of 10 mM 4-nitrophenol was added to 3 mL of distilled water in a quartz cuvette, followed by the addition of 20 μL of colloidal NPs for studying the catalytic performance of prepared mono- and BMPs colloidal NPs for the reduction of nitrophenol. Immediately after the addition of 200 μL of 500 mM NaBH4, the sample was analyzed spectrophotometrically. To study the progress of the catalytic reaction, absorption spectra were recorded at regular intervals of time until the yellow color of the solution disappears.

The catalytic degradation of rhodamine B and indigo carmine dyes was analyzed by taking 1.5 mL of 0.0001 mM rhodamine B and 0.0004 mM indigo carmine separately in a quartz cuvette. To the corresponding dye solution were added 100 μL of colloidal NPs and 20 μL of 50 mM NaBH4. Immediately after this, absorption spectrum was recorded. The progress of the reaction was studied by recording spectra at regular intervals of time until the reddish pink of rhodamine B and blue color of indigo carmine dyes vanished.

Antibacterial Activity

In vitro antibacterial activity of Gram-positive bacteria such as Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and E. faecium as well as Gram-negative bacteria such as V.cholerae, E. coli, A. hydrophila, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, A. baumannii, S. flexneri, and P. aeruginosa were used for the antibacterial effect assay.

The in vitro antibacterial activity of synthesized NPs was analyzed using the Mueller–Hinton Agar diffusion method, in which the diameter of inhibition zone was measured. In the present study, Gram-positive bacteria such as Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and E. faecium as well as Gram-negative bacteria such as V.cholerae, E. coli, A. hydrophila, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium, A. baumannii, S. flexneri, and P. aeruginosa were used for the antibacterial effect assay. Distilled water was used as the control.

For the preparation of bacterial strains, freshly subcultured bacteria strains were inoculated into Muller–Hinton broth, incubated for 4 h at 37 °C, and adjusted to a turbidity of 0.5 McFarland standards. An agar well diffusion method was used to evaluate antimicrobial activity of the nanoparticles. Wells of diameter 6 mm each were punched in the Muller–Hinton agar by a sterile borer and filled with 70 μL of colloidal nanoparticles product. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the diameters of the zone of inhibition of growth were measured and compared with that of control.

Acknowledgments

Shilpa Molakkalu Padre, Gurumurthy Sangam Chandrasekhar, and Mamatha Ballal acknowledge Manipal Academy of Higher Education for the funding facility. S. Kiruthika acknowledges SASTRA University, funding from SERB POWER Grant No. SPG/2020/000442, and DST for support through the DST-FIST Project (SR/FST/PS-1/2020/135). The authors are also grateful to the Mangalore University DST-PURSE laboratory for providing the FESEM and other facilities. Authors Srivathsava Surabhi and Jong-Ryul Jeong are greatly indebted to their organizations Universidad de Concepción (UdeC) (Programa Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT-postdoctoral Project No 3200832) de la Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID), Chile), ESSS (Engineering Simulation Scientific Software) Chile SPA, and Chungnam National University, South Korea (NRF-South Korea Project No 2020R1A2C100613611) for simulation-related support and facilities.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c03784.

EDAX spectra of BMPs, simulation studies, brief note on the effect of pH on morphology and spectroscopy, deconvoluted XRD of CuAg BMPs, catalytic degradation studies of rhodamine B and indigo carmine dye, and Mueller–Hinton Agar diffusion method for evaluating antibacterial activity of Au, Ag, and Cu NPs against various bacteria (PDF)

Author Contributions

The study was designed, planned, and experimentally initiated by Shilpa Molakkalu Padre and Gurumurthy Chandrasekhar Sangam. Mamatha Ballal and Vignesh Shetty are associated with the experiments and characterizations, and Mudiyaru Subrahmanya Murari, Shridhar Mundinamani, Ravikirana, Kunaberu Mallikarjunappa Eshwarappa, and S. Kiruthika helped with data curation and analysis. Srivathsava Surabhi and Jong-Ryul Jeong performed the simulations. Shilpa Molakkalu Padre, Srivathsava Surabhi, and Gurumurthy S C wrote the manuscript, while all of the other authors have offered their support for revision and analysis. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability. The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time due to technical or time limitations.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aragay G.; Pino F.; Merkoçi A. Nanomaterials for Sensing and Destroying Pesticides. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112 (10), 5317–5338. 10.1021/cr300020c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M. J.; Billingsley M. M.; Haley R. M.; Wechsler M. E.; Peppas N. A.; Langer R. Engineering Precision Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2021, 20, 101–124. 10.1038/s41573-020-0090-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak A.; Szade J.; Talik E.; Zubko M.; Wasilkowski D.; Dulski M.; Balin K.; Mrozik A.; Peszke J. Physicochemical and Antibacterial Characterization of Ionocity Ag/Cu Powder Nanoparticles. Mater. Charact 2016, 117, 9–16. 10.1016/j.matchar.2016.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Z.; Zhang Z.; Bi S. Nanoparticles for Organic Electronics Applications. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7 (1), 012004. 10.1088/2053-1591/ab636f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Astruc D. Introduction: Nanoparticles in Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120 (2), 461–463. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papavassiliou G. C. Surface Plasmons in Small Au-Ag Alloy Particles. J. Phys. F Met Phys. 1976, 6 (4), L103. 10.1088/0305-4608/6/4/004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G.; Naushad M.; Kumar A.; Devi S.; Khan M. R. Lanthanum/Cadmium/Polyaniline Bimetallic Nanocomposite for the Photodegradation of Organic Pollutant. Iran Polym. J. 2015, 24 (12), 1003–1013. 10.1007/s13726-015-0388-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Van P.; Surabhi S.; Quoc V. D.; Lee J. W.; Tae C. C.; Kuchi R.; Jeong J.-R. Broadband Tunable Plasmonic Substrate Using Self-Assembled Gold-Silver Alloy Nanoparticles. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2019, 19 (11), 1245–1251. 10.1016/j.cap.2019.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F.; Yao Y.; Jiang C.; Shao Y.; Barceló D.; Ying Y.; Ping J. Self-Reduction Bimetallic Nanoparticles on Ultrathin MXene Nanosheets as Functional Platform for Pesticide Sensing. J. Hazard Mater. 2020, 384, 121358. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loza K.; Heggen M.; Epple M.; Loza K.; Epple M.; Heggen M. Synthesis, Structure, Properties, and Applications of Bimetallic Nanoparticles of Noble Metals. Adv. Funct Mater. 2020, 30 (21), 1909260. 10.1002/adfm.201909260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y.; Lan L.; Li X.; Liu X.; Ying Y.; Ping J. Noble Metal Regeneration: Alchemy-Inspired Green Paper for Spontaneous Recovery of Noble Metals (Small 33/2020). Small 2020, 16 (33), 2070184. 10.1002/smll.202070184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouyau J.; Duval R.; Boudier A.; Lamouroux E.; Duval R. E. Investigation of Nanoparticle Metallic Core Antibacterial Activity: Gold and Silver Nanoparticles against Escherichia Coli and Staphylococcus Aureus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22 (4), 1905. 10.3390/ijms22041905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G.; Kumar A.; Sharma S.; Naushad M.; Prakash Dwivedi R.; ALOthman Z. A.; Mola G. T. Novel Development of Nanoparticles to Bimetallic Nanoparticles and Their Composites: A Review. J. King Saud Univ Sci. 2019, 31 (2), 257–269. 10.1016/j.jksus.2017.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh K. H.; Pham X. H.; Kim J.; Lee S. H.; Chang H.; Rho W. Y.; Jun B. H. Synthesis, Properties, and Biological Applications of Metallic Alloy Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21 (14), 5174. 10.3390/ijms21145174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paszkiewicz M.; Gołąbiewska A.; Rajski Ł.; Kowal E.; Sajdak A.; Zaleska-Medynska A. Synthesis and Characterization of Monometallic (Ag, Cu) and Bimetallic Ag-Cu Particles for Antibacterial and Antifungal Applications. J. Nanomater 2016, 2016, 1–11. 10.1155/2016/2187940. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tantawy H. R.; Nada A. A.; Baraka A.; Elsayed M. A. Novel Synthesis of Bimetallic Ag-Cu Nanocatalysts for Rapid Oxidative and Reductive Degradation of Anionic and Cationic Dyes. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 3, 100056. 10.1016/j.apsadv.2021.100056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borah R.; Verbruggen S. W. Silver-Gold Bimetallic Alloy versus Core-Shell Nanoparticles: Implications for Plasmonic Enhancement and Photothermal Applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124 (22), 12081–12094. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c02630. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holden M. S.; Nick K. E.; Hall M.; Milligan J. R.; Chen Q.; Perry C. C. Synthesis and Catalytic Activity of Pluronic Stabilized Silver-Gold Bimetallic Nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2014, 4 (94), 52279–52288. 10.1039/C4RA07581A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaria J.; Nidheesh P. V.; Kumar M. S. Synthesis and Applications of Various Bimetallic Nanomaterials in Water and Wastewater Treatment. J. Env. Manage 2020, 259, 110011. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.110011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu W.; Zhao H.; Zhang Q.; Xia D.; Tang Z.; Chen Q.; He C.; Shu D. Multifunctional Au/Ti3C2Photothermal Membrane with Antibacterial Ability for Stable and Efficient Solar Water Purification under the Full Spectrum. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9 (34), 11372–11387. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c03096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranga Reddy P.; Varaprasad K.; Narayana Reddy N.; Mohana Raju K.; Reddy N. S. Fabrication of Au and Ag Bi-Metallic Nanocomposite for Antimicrobial Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 125 (2), 1357–1362. 10.1002/app.35192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Areeb A.; Yousaf T.; Murtaza M.; Zahra M.; Zafar M. I.; Waseem A. Green Photocatalyst Cu/NiO Doped Zirconia for the Removal of Environmental Pollutants. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 28, 102678. 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lellis B.; Fávaro-Polonio C. Z.; Pamphile J. A.; Polonio J. C. Effects of Textile Dyes on Health and the Environment and Bioremediation Potential of Living Organisms. Biotechnol Res. Innov 2019, 3 (2), 275–290. 10.1016/j.biori.2019.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva I. O.; Ladchumananandasivam R.; Nascimento J. H. O.; Silva K. K. O. S.; Oliveira F. R.; Souto A. P.; Felgueiras H. P.; Zille A. Multifunctional Chitosan/Gold Nanoparticles Coatings for Biomedical Textiles. Nanomaterials 2019, 9 (8), 1064. 10.3390/nano9081064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berradi M.; Hsissou R.; Khudhair M.; Assouag M.; Cherkaoui O.; El Bachiri A.; El Harfi A. Textile Finishing Dyes and Their Impact on Aquatic Environs. Heliyon 2019, 5 (11), e02711 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tara N.; Siddiqui S. I.; Rathi G.; Chaudhry S. A.; Inamuddin; Asiri A. M. Nano-Engineered Adsorbent for the Removal of Dyes from Water: A Review. Curr. Anal Chem. 2020, 16 (1), 14–40. 10.2174/1573411015666190117124344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail M.; Khan M. I.; Khan S. B.; Khan M. A.; Akhtar K.; Asiri A. M. Green Synthesis of Plant Supported CuAg and CuNi Bimetallic Nanoparticles in the Reduction of Nitrophenols and Organic Dyes for Water Treatment. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 260, 78–91. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.03.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S.; Mathew B. Facile Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Application in Dye Degradation. Mater. Sci. Eng., B 2015, 195, 90–97. 10.1016/j.mseb.2015.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berahim N.; Basirun W. J.; Leo B. F.; Johan M. R. Synthesis of Bimetallic Gold-Silver (Au-Ag) Nanoparticles for the Catalytic Reduction of 4-Nitrophenol to 4-Aminophenol. Catalysts 2018, 8 (10), 412. 10.3390/catal8100412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee M.; Sharma S.; Chattopadhyay A.; Ghosh S. S. Enhanced Antibacterial Activity of Bimetallic Gold-Silver Core-Shell Nanoparticles at Low Silver Concentration. Nanoscale 2011, 3 (12), 5120–5125. 10.1039/c1nr10703h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-S.; Ryu D.-S.; Choi S.-J.; Lee D.-S. Antibacterial Activity of Silver-Nanoparticles Against Staphylococcus Aureus and Escherichia Coli. Korean J. Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 39 (1), 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Katas H.; Lim C. S.; Nor Azlan A. Y. H.; Buang F.; Mh Busra M. F. Antibacterial Activity of Biosynthesized Gold Nanoparticles Using Biomolecules from Lignosus Rhinocerotis and Chitosan. Saudi Pharm. J. 2019, 27 (2), 283–292. 10.1016/j.jsps.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbewana-Ntshanka N. G.; Moloto M. J.; Mubiayi P. K. Antimicrobial Activity of the Synthesized of Copper Chalcogenide Nanoparticles. J. Nanotechnol 2021, 2021, 1–14. 10.1155/2021/6675145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gawande M. B.; Goswami A.; Felpin F.-X.; Asefa T.; Huang X.; Silva R.; Zou X.; Zboril R.; Varma R. S. Cu and Cu-Based Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Applications in Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3722–3811. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq S.; Araujo R. E. de; Farooq S.; Araujo R. E.de. Engineering a Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Platform for Molecular Biosensing. Open J. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8 (3), 126–139. 10.4236/ojapps.2018.83010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H.; Cho H. Y.; Choi H. K.; Lee J. Y.; Choi J. W. Application of Gold Nanoparticle to Plasmonic Biosensors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19 (7), 2021. 10.3390/ijms19072021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero-Quiroz C.; Acevedo N.; Zapata-Giraldo J.; Botero L. E.; Quintero J.; Zárate-Trivinõ D.; Saldarriaga J.; Pérez V. Z. Optimization of Silver Nanoparticle Synthesis by Chemical Reduction and Evaluation of Its Antimicrobial and Toxic Activity. Biomater Res. 2019, 23 (1), 27. 10.1186/s40824-019-0173-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiseau A.; Asila V.; Boitel-Aullen G.; Lam M.; Salmain M.; Boujday S. Silver-Based Plasmonic Nanoparticles for and Their Use in Biosensing. Biosensors 2019, 9 (2), 78. 10.3390/bios9020078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valodkar M.; Modi S.; Pal A.; Thakore S. Synthesis and Anti-Bacterial Activity of Cu, Ag and Cu-Ag Alloy Nanoparticles: A Green Approach. Mater. Res. Bull. 2011, 46 (3), 384–389. 10.1016/j.materresbull.2010.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yaqoob A. A.; Parveen T.; Umar K.; Ibrahim M. N. M. Role of Nanomaterials in the Treatment of Wastewater: A Review. Water 2020, 12 (2), 495. 10.3390/w12020495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malasi A.; Taz H.; Ehrsam M.; Goodwin J.; Garcia H.; Kalyanaraman R. Enhanced and Tunable Optical Quantum Efficiencies from Plasmon Bandwidth Engineering in Bimetallic CoAg Nanoparticles. APL Photonics 2016, 1, 76101. 10.1063/1.4954698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z.; Murakami N.; Liu J.; Teng Z.; Zhang Q.; Cao Y.; Cheng H.; Ohno T. Development of Plasmonic Photocatalyst by Site-Selective Loading of Bimetallic Nanoparticles of Au and Ag on Titanium(IV) Oxide. ChemCatChem. 2020, 12 (14), 3783–3792. 10.1002/cctc.202000366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reineck P.; Brick D.; Mulvaney P.; Bach U. Plasmonic Hot Electron Solar Cells: The Effect of Nanoparticle Size on Quantum Efficiency. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7 (20), 4137–4141. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b01884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhulata S.; Indrajit S.. Nanocatalysts; BoD - Books on Demand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto Y.; Seniutinas G.; Balcytis A.; Juodkazis S.; Nishijima Y. Au-Ag-Cu Nano-Alloys: Tailoring of Permittivity. Sci. Rep 2016, 6 (1), 25010. 10.1038/srep25010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N.; Han C.; Fu X.; Xu Y. J. Function-Oriented Engineering of Metal-Based Nanohybrids for Photoredox Catalysis: Exerting Plasmonic Effect and Beyond. Chem. 2018, 4 (8), 1832–1861. 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LumericalFDTD - High-Performance Photonic Simulation Software. https://www.lumerical.com/ (accessed 2022-01-05).

- Peiris S.; McMurtrie J.; Zhu H. Y. Metal Nanoparticle Photocatalysts: Emerging Processes for Green Organic Synthesis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6 (2), 320–338. 10.1039/C5CY02048D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawawaki T.; Mori Y.; Wakamatsu K.; Ozaki S.; Kawachi M.; Hossain S.; Negishi Y. Controlled Colloidal Metal Nanoparticles and Nanoclusters: Recent Applications as Cocatalysts for Improving Photocatalytic Water-Splitting Activity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8 (32), 16081–16113. 10.1039/D0TA04750C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linic S.; Aslam U.; Boerigter C.; Morabito M. Photochemical Transformations on Plasmonic Metal Nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14 (6), 567–576. 10.1038/nmat4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Shi J.; Kawamura G.; Nogami M. Preparation of Au-Ag, Ag-Au Core-Shell Bimetallic Nanoparticles for Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Scr Mater. 2008, 58 (10), 862–865. 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2008.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dang T. M. D.; Le T. T. T.; Fribourg-Blanc E.; Dang M. C. Synthesis and Optical Properties of Copper Nanoparticles Prepared by a Chemical Reduction Method. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci Nanotechnol 2011, 2 (1), 015009. 10.1088/2043-6262/2/1/015009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman L. U.; Qureshi R.; Yasinzai M. M.; Shah A. Synthesis and Spectroscopic Characterization of Ag-Cu Alloy Nanoparticles Prepared in Various Ratios. C R Chim 2012, 15 (6), 533–538. 10.1016/j.crci.2012.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi H.; Kushwaha A.; Kumar A.; Aslam M. A Facile PH Controlled Citrate-Based Reduction Method for Gold Nanoparticle Synthesis at Room Temperature. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11 (1), 1–11. 10.1186/s11671-016-1576-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arboleda D. M.; Santillán J. M. J.; Arce V. B.; Fernández van Raap M. B.; Muraca D.; Fernández M. A.; Torres Sanchez R. M.; Schinca D. C.; Scaffardi L. B. A Simple and “Green” Technique to Synthesize Long-Term Stability Colloidal Ag Nanoparticles: Fs Laser Ablation in a Biocompatible Aqueous Medium. Mater. Charact 2018, 140, 320–332. 10.1016/j.matchar.2018.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dung Dang T. M.; Tuyet Le T. T.; Fribourg-Blanc E.; Chien Dang M. The Influence of Solvents and Surfactants on the Preparation of Copper Nanoparticles by a Chemical Reduction Method. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci Nanotechnol 2011, 2 (2), 025004. 10.1088/2043-6262/2/2/025004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Refractiveindex.info (accessed Refractiveindex.info-08-31).

- Palik E. D.Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids; Palik E. D., Ed.; Elsevier, Inc., 1985; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rioux D.; Vallières S.; Besner S.; Muñoz P.; Mazur E.; Meunier M. An Analytic Model for the Dielectric Function of Au, Ag, and Their Alloys. Adv. Opt Mater. 2014, 2 (2), 176–182. 10.1002/adom.201300457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boomi P.; Poorani G. P.; Palanisamy S.; Selvam S.; Ramanathan G.; Ravikumar S.; Barabadi H.; Prabu H. G.; Jeyakanthan J.; Saravanan M. Evaluation of Antibacterial and Anticancer Potential of Polyaniline-Bimetal Nanocomposites Synthesized from Chemical Reduction Method. J. Clust Sci. 2019, 30 (3), 715–726. 10.1007/s10876-019-01530-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.; Wang Y.; Hao H. Investigations on Dehydration Processes of Trisodium Citrate Hydrates. Front Chem. Sci. Eng. 2012, 6 (3), 276–281. 10.1007/s11705-012-1206-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanien A. S.; Khatoon U. T. Synthesis and Characterization of Stable Silver Nanoparticles, Ag-NPs: Discussion on the Applications of Ag-NPs as Antimicrobial Agents. Phys. B Condens Matter 2019, 554, 21–30. 10.1016/j.physb.2018.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raja M.; Subha J.; Ali F. B.; Ryu S. H. Synthesis of Copper Nanoparticles by Electroreduction Process. Mater. Manuf 2008, 23 (8), 782–785. 10.1080/10426910802382080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mooradian A. Photoluminescence of Metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1969, 22 (5), 185. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.22.185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazyan T. V. Theory of Plasmon-Enhanced Metal Photoluminescence. Nano Lett. 2013, 13 (1), 194–198. 10.1021/nl303851z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Jiang Y.; Fang Y. Spectroscopy Property of Ag Nanoparticles. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol Spectrosc 2006, 65 (5), 1003–1006. 10.1016/j.saa.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. I.; Chen W. T.; Chang H. T. Enzyme Mimics of Au/Ag Nanoparticles for Fluorescent Detection of Acetylcholine. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84 (22), 9706–9712. 10.1021/ac300867s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogireddy N. K. R.; Kiran Kumar H. A.; Mandal B. K. Biofabricated Silver Nanoparticles as Green Catalyst in the Degradation of Different Textile Dyes. J. Env. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4 (1), 56–64. 10.1016/j.jece.2015.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein M. J.; Yunus W. M. M.; Kamari H. M.; Zakaria A.; Oleiw H. F. Effect of Current Density and Etching Time on Photoluminescence and Energy Band Gap of P-Type Porous Silicon. Opt Quantum Electron 2016, 48 (3), 1–8. 10.1007/s11082-016-0476-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Din M. I.; Khalid R.; Hussain Z.; Hussain T.; Mujahid A.; Najeeb J.; Izhar F. Nanocatalytic Assemblies for Catalytic Reduction of Nitrophenols: A Critical Review. Crit Rev. Anal Chem. 2020, 50 (4), 322–338. 10.1080/10408347.2019.1637241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaban M.; Elwahab F. A.; Ghitas A. E.; El Zayat M. Y. Efficient and Recyclable Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye in Aqueous Solutions Using Nanostructured Cd1 - XCoxS Films of Different Doping Levels. J. Solgel Sci. Technol. 2020, 95 (2), 276–288. 10.1007/s10971-020-05331-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi G.; Ayodhya D.; Madderla S.; Dongamanti A. Facile Fabrication, Characterization and Enhanced Heterogeneous Catalytic Reduction of 4-Nitrophenol Using Undoped and Doped ZrO2 Nanoparticles. Nanochem Res. 2019, 4 (1), 43–54. 10.22036/NCR.2019.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raj S.; Singh H.; Trivedi R.; Soni V. Biogenic Synthesis of Ag NPs Employing Terminalia Arjuna Leaf Extract and Its Efficacy towards Catalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes. Sci. Rep 2020, 10 (1), 1–10. 10.1038/s41598-020-66851-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H. P.; Gupta N.; Sharma S. K.; Sharma R. K. Synthesis of Bimetallic Pt-Cu Nanoparticles and Their Application in the Reduction of Rhodamine B. Colloid Surf. -Physicochem Eng. Asp 2013, 416 (1), 43–50. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2012.09.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna M.; Rajesh Babu D.; Gengan R. M.; Chandra S.; Nageswara Rao G. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Marine Algae and Evaluation of Their Catalytic Activity. J. Nanostructure Chem. 2016, 6 (1), 1–13. 10.1007/s40097-015-0173-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balouiri M.; Sadiki M.; Ibnsouda S. K. Methods for in Vitro Evaluating Antimicrobial Activity: A Review. J. Pharm. Anal 2016, 6 (2), 71–79. 10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin Y. N.; Asnis J.; Häfeli U. O.; Bach H. Metal Nanoparticles: Understanding the Mechanisms behind Antibacterial Activity. J. Nanobiotechno 2017, 15, 1–20. 10.1186/s12951-017-0308-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.