Abstract

The influence of the moisture content on the ignition and combustion characteristics of lignite single particles was studied using an ignition model of single coal particles with moisture and experimental investigations in a visual drop tube furnace under the temperature of 1300 K. The moisture content and the lignite particle size were varied within the ranges of 0–20% and 75–250 μm, respectively. The images of the combustion process illustrated that higher moisture content caused a significant ignition delay. The probability of homogeneous ignition was greatest when the particle size was 125–150 μm and the moisture content was 5%. An ignition model was employed to explain the mechanism of the influence of moisture content on the ignition and combustion characteristics, which embedded the chemical percolation devolatilization model to increase the accuracy of predictions. The predicted results show that there was an overlap in the release of moisture and volatile matter from the lignite particle during the combustion at a high heating rate. The devolatilization rate increases with the increase of moisture, which explains the increase in the probability of homogeneous ignition and fragmentation. Both particle size and moisture content have two-sided effects on the ignition mode, which causes the complexity and irregularity of the ignition mode of particles with moisture.

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth in the economy and an increase in energy requirement, coal is still the dominant energy resource.1 The combustion of lignite has gradually attracted attention because it is low-grade coal with the advantages of low mining cost, rich reserves, high content of volatile matter, and low amount of pollution-forming elements.2−4 However, the utilization of lignite is limited due to its disadvantage of high moisture content and low calorific value.5 The moisture content of lignite in China is generally 25–40%,6 while the moisture content of lignite mined in Australia’s Latrobe valley can be as high as 55–70%.7 Therefore, lignite is generally dried before combustion, but the conventional hot-dry processes cannot guarantee the complete removal of moisture in coals.8

Moisture may change the combustion characteristics of coal.9 Tahmasebi et al.10 studied the effects of moisture content on ignition and combustion behavior of Chinese and Indonesian lignite particles with the particle size in the range of 75–105 μm at temperatures of 400–550 °C. The results showed that the ignition delays increased by 83 and 160 ms when the moisture contents were 10 and 20%, respectively. In addition, high moisture content leads to an increase in fragmentation. Clemems et al.11 suggested that the moisture content did not affect the diffusion of oxygen to the functional group on the surface of coal when the coal contained 5–10% moisture at low temperatures, whereas the increase in moisture content accelerated the formation of peroxide. Zhai et al.9 studied the effect of moisture immersion on active functional groups and characteristic temperatures of bituminous coal. The results revealed that soaked coals were more prone to spontaneous combustion than raw coal because of changes in the number of functional groups and characteristic temperature. It is generally believed that moisture is released completely from coal particles before devolatilization and has no effect on its ignition mode. Prationoa et al.12 studied the combustion process of Victoria lignite with particle size in the range of 63–104 μm and moisture content of 30% using a flat flame burner reactor and modeling. The results showed that only 10% of moisture was distilled before devolatilization. Therefore, the ignition mode of coal can be changed due to the moisture in pulverized coal particles. However, there are rare reports about the influence of moisture on ignition mode, and the problem only focuses on particle size,13,14 heating rate,15 coal rank,16,17 and ambient temperature.18,19

In this study, the primary objective was to understand the effects of moisture content on the combustion characteristics of lignite particles using a visual drop tube furnace, such as ignition mode, ignition delay time, burnout time, and combustion fragmentation of lignite with different particle sizes through experimental study. Simultaneously, an ignition model of a single particle with moisture was used to analyze the influence mechanism of moisture content on ignition mode.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Effect of Moisture Content on Ignition and Combustion Behavior

To explore the influence of moisture content on ignition and combustion characteristics of lignite particles, the combustion behavior of samples with different moisture contents and particle sizes at 1300 K was recorded, as shown in Figure 1. A pulverized coal particle can occur via either gas-phase combustion of the released VM (homogeneous ignition mode) or heterogeneous ignition of the particle surface (heterogeneous ignition mode).13 It is observed that the samples with a particle size of 75–90 μm have a higher probability of undergoing a homogeneous ignition mode when the moisture content is 5%, and the particles with other moisture contents are directly ignited in heterogeneous ignition. The lignite particles with a moisture content of 5% are ignited by the homogeneous ignition mode, which results in the two-stage burning of volatile combustion, followed by shrinking-core char combustion when the particle size is in the range of 125–150 μm. However, the samples with the moisture content of 10 and 20% experience gas phase volatile combustion and heterogeneous combustion simultaneously, this phenomenon is usually regarded as hetero-homogeneous ignition mode. It can be seen that the increase in the moisture content intensifies the oxidation of carbon, which is related to the increase in pore surface area and the content of oxygen atoms during the evaporation of moisture.20,21 However, when the range of particle size is increased to 200–250 μm, the probability of the homogeneous ignition of lignite particles with moisture is not improved. The samples with moisture have a higher probability of undergoing homogeneous ignition than the dry samples with particle sizes smaller than 150 μm, and the probability decreases when the particle size is above 200 μm. Therefore, moisture content has a very important influence on the ignition mode of particles, and there are optimum values for the particle size and moisture content.

Figure 1.

Combustion behaviors of samples of different moisture contents and particle sizes of (a) 75–90 μm, (b) 125–150 μm, and (c) 200–250 μm.

At the same time, it is found that the characteristics of homogeneous combustion flame of the samples with moisture are different from those of dry samples. The flame of volatile combustion is mostly of a regular spherical shape, whereas the outer edge of the flame is light blue.14,22 The reason is that the release of moisture and volatile matter increases the buoyancy and weakens the convective intensity of pulverized coal particles, resulting in the flame taking a regular spherical shape. On the other hand, the char and moisture reaction increases the release of CO and H2 (C + H2O = CO + H2 + 131.85 kJ/kg). Therefore, the volatile matter can burn in a short distance. Meanwhile, the moisture may lead to the increase in oxygen-containing functional groups and oxygen atoms12 so that the combustible gas can maintain the dynamic combustion state and the outer edge of the flame becomes light blue.

It is worth noticing that all of the particles of different sizes with moisture are broken during combustion. Moisture leads to fragmentations during the combustion of particles, while the dry particles do not break when the particle size is in the range of 200–250 μm. Therefore, higher moisture contents are found to lead to a higher possibility of fragmentation.

The study found that due to the individual differences of particles, various ignition modes can coexist under the same experimental conditions. Figure 2 shows that the proportion of particles in each ignition mode is statistically analyzed by the photos obtained from the visual drop tube furnace (VDTF). The various ignition modes in samples with moisture are more obvious. Therefore, moisture increases the diversity and complexity of ignition modes. The particle with a size below 150 μm increases the possibility of homogeneous ignition due to the presence of moisture. However, the increase in moisture content or the particle size does not increase the rate of homogeneous or hetero-homogeneous ignition. The probability of gas-phase ignition of particles with a moisture content of 5% and particle size of 125–150 μm is the highest, and the ignition mode is transformed from homogeneous to hetero-homogeneous ignition with an increase in moisture content from 5 to 10%.

Figure 2.

Proportion of particles in each ignition mode under different experimental conditions.

2.2. Effect of Moisture Content on the Characteristic Time of Combustion

The ignition delay is a critical parameter to distinguish the reactivity of coal. The ignition delay of particles in the visual drop tube furnace (VDTF) can be recorded by a high-speed camera. The average ignition delay time of more than 40 particles under each experimental condition was counted. The average ignition delays of the samples are recorded in Figure 3. Figure 3 illustrates that the ignition delay increases with the increase of moisture content. Meanwhile, the moisture content has a more obvious effect on the ignition delay of large particles. When the particle size is 200–250 μm, the ignition delays of particles with moisture contents of 10 and 20% are 15 and 45 ms, respectively. However, the ignition delay of particles with moisture contents of 5 and 10% is very close to those of dry particles of lignite for the particle size of 75–90 μm. Therefore, the fluctuations in moisture content have almost no effect on ignition delay when the particle size is below 90 μm and the moisture content is less than 10%.

Figure 3.

Effect of particle size and moisture content on ignition delay from VDTF experience.

The burnout time of particles can be obtained by ignition image from the VDTF experiment, and the calculation method was similar to that of the ignition delay. The burnout times of lignite particles with different particle sizes and moisture contents are summarized in Figure 4. It can be seen from Figure 4 that the burnout time increased with the increase of particle size and moisture content, which is related to the increase in the degree of fragmentation during the combustion of particles with higher moisture content. The burnout time of dry lignite particles with a particle size of 200–250 μm is as high as 160 ms, which is twice the burnout time of particles with a moisture content of 5%. This is due to the absence of fragmentation in dry lignite particles.

Figure 4.

Effect of particle size and moisture content on the burnout time from VDTF experience.

2.3. Mechanism of the Influence of Moisture Content on the Ignition and Combustion of Particle

2.3.1. Influence of Moisture Content on the Ignition

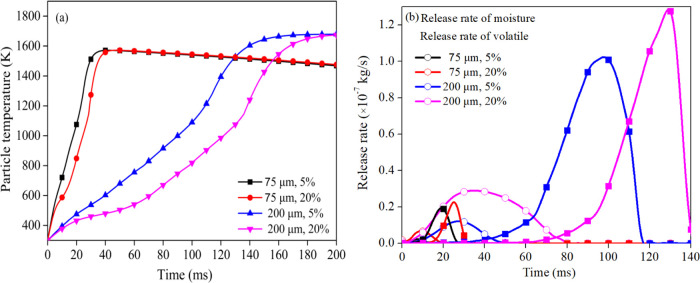

The VDTF experimental results show that the possibility of homogeneous ignition increases due to the moisture in the lignite particle. To explore the influencing mechanism of moisture on the ignition and combustion characteristics, the combustion process of lignite particles with different moisture contents is simulated using the ignition model of single coal particles with moisture. Figure 5 shows the simulation results of the combustion process of lignite particles with different moisture contents and the particle size of 125 μm at 1300 K. Figure 5a shows the effects of moisture on the curves of particle heating and the release of volatile matter. The heating rates of particles and the release rate of the volatile matter in the initial stage decreased with the increase in moisture content, which is due to the gasification latent heat required for the evaporation of moisture. Therefore, the particle ignition delay increased with the increase of moisture content. Figure 5b shows the rate of release of moisture and volatile matter. It is observed that there is an overlapping of moisture and volatile release curves. The moisture release overlaps with the volatile matter and accounts for 1.25 and 3.7% of volatile matter and moisture overlapping release when the moisture contents are 5 and 20%, respectively. It illustrates that the higher the moisture content, the lower the initial release concentration of volatiles. Hence, the particle with higher moisture content has a lower possibility of homogeneous ignition. On the other hand, the increase in moisture content promotes the release of volatile matter. It can be seen from the energy conservation that the higher the moisture content, the greater the rate of heat loss of moisture, which increases the temperature difference between the particles and the surrounding environment and increases the rate of radiation heat and convective heat transfer rate provided to the particles by the environment. This is in turn due to the acceleration of the particle heating rate during the release of volatile matter. The concentrated release of volatile matter explains the increase of homogeneous ignition and fragmentation during the combustion of lignite particles with moisture. Although the increase in moisture content promoted the concentrated release of volatiles, it is a factor conducive to the occurrence of homogeneous ignition while reducing the release of volatile matter, which is disadvantageous to homogeneous ignition. Therefore, there is an optimal moisture content for homogeneous ignition.

Figure 5.

Simulation results with samples with different moisture contents: (a) particle temperature and production of volatile matter; (b) rate of moisture and volatile release.

2.3.2. Effect of Moisture Content on the Ignition Characteristics of Particles of Different Sizes

The VDTF experimental results show that the influence of moisture content on ignition and combustion characteristics of lignite particles of different sizes is very obvious. The experimental results show that the proportion of homogeneous ignition within the particle size range of 125–150 μm is the largest under different moisture contents. To analyze the influence of the coupling effect of moisture content and particle size on the ignition characteristics, the combustion process of lignite particles with moisture contents of 5 and 20% and particle sizes of 75 and 200 μm is simulated, as shown in Figure 6. Figure 6a shows the heating rate of the particles under different conditions. It shows that moisture has only a slight effect on the heating rate of smaller particles, which reveals the reason why moisture has little effect on the ignition delay of particles of small size. Figure 6b shows the release rates of moisture and volatile matter. As shown in Figure 6b, for the particles with moisture content and size of 5% and 75 μm, 20% and 75 μm, 5% and 200 μm, and 20% and 200 μm, the moisture release overlaps with the volatile matter and accounts for 0.9% (1.7 × 10–12 kg), 2.4% (4.56 × 10–12 kg), 0.6% (2.17 × 10–11 kg), and 0.8% (2.9 × 10–11 kg) of the total volatile matter, respectively. Increasing the moisture increases the overlapping release of moisture and volatiles, especially for smaller particles. Reducing the particle size increases the heating rate, but the amount of volatile matter released is small, and the proportion of overlapped moisture and volatile matter is high, especially at a high moisture content. It reveals the mechanism that moisture significantly affects the ignition mode of smaller particles (as shown in Figure 2). Increasing the particle size can increase the release of volatile matter, which is conducive to the homogeneous ignition of coal particles. The proportion of the homogeneous ignition mode increases with the increase of the particle size for dry pulverized coal particles.13,14,16 However, this characteristic does not appear in the experimental results of particles with moisture. To reveal the reasons, the temperature difference between the center and surface of the particles with different particle sizes and moisture contents are simulated. Figure 7 shows the temperature difference of the particles when the average temperature of the particles is 373 K. The results indicate that the temperature difference increases with the increase of the particle size and moisture content. Therefore, the central moisture release rate of large-sized particles lags behind the average release rate, due to which the moisture of large-sized particles has a greater impact on the initial release of volatile matter. On the other hand, the central moisture that cannot be released quickly may block the voids of coal particles, thereby inhibiting the release of volatiles. Therefore, compared with dry pulverized coal, moisture reduces the probability of homogeneous ignition of larger particles. The particle size has two sides to the homogeneous ignition of the lignite particle with moisture. Therefore, the ignition mode is determined by the coupling of moisture and particle size and has an optimal particle size for homogeneous ignition mode.

Figure 6.

Simulation results for samples with different particle sizes and moisture contents at 1300 K: (a) particle temperature; (b) rates of release of moisture content and volatile matter.

Figure 7.

Temperature difference between the inside and outside of particle.

3. Conclusions

In this paper, the visual experiment and simulation were used to study the effect of moisture content on combustion characteristics. The following conclusions are drawn.

The moisture increases the complexity and diversity of the ignition mode of lignite particles. The probability of homogeneous ignition does not increase with the increasing particle size, which is different from the dry coal particles. The probability of homogeneous ignition is greatest when the particle size is 125–150 μm and the moisture content is 5%.

The effect of volatile pyrolysis and volatile combustion heat on particle heating can be more effectively predicted when the chemical percolation devolatilization (CPD) model is embedded in the ignition model of a single particle with moisture.

Moisture promotes the concentrated release of volatiles, while the increase of moisture reduces the initial release concentration of volatiles (the volatiles released by overlapping with moisture account for 1.25 and 3.7% of the total volatiles, and when the moisture content is 5 and 20%, respectively). The moisture content and particle size have a two-sided effect on the ignition mode of the particle with moisture.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Preparation

Lignite produced in China was used in the present study. The results from the proximate analysis (ad%) were as follows: FCad = 34.27%; Vad = 39.76%; Mad = 21.41%; Aad = 4.56%. The results from the ultimate analysis (daf%) were as follows: Cdaf = 65.82%; Hdaf = 4.51%; Odaf = 28.78%; Ndaf = 0.89%. To explore the influence of moisture content on ignition and combustion characteristics of samples with different particle sizes, the lignite was separately crushed and sieved to 75–90, 125–150, and 200–250 μm, and they were dried to achieve the moisture contents of 20, 10, 5, and 0%, respectively. The preparation process of particles with different moisture contents is as follows: (i) the samples (1 ± 0.1 g) with different particle sizes were dried in a drying oven on forced convection at the temperature of 105 °C until the weight became constant and the moisture content was calculated as received base (Mar); (ii) the sample of each particle size was divided into 20 equal parts with a mass of 1 ± 0.1 g, and they were also dried at 105 °C; and (iii) a sample was taken out every 2 min, and the rate of moisture content was calculated according to eq 1. The moisture loss curve of the three particle sizes is shown in Figure 8. Finally, the samples with the moisture content of 20, 10, 5, and 0% (error of less than ± 0.5%) were prepared by adjusting the residence time according to the moisture loss curve.

| 1 |

where Mi is the moisture content of the sample at time i (%), m0 is the mass of the sample before drying (kg), and mM is the mass of the sample at time i (kg)

Figure 8.

Moisture loss curve of samples with different particle sizes.

4.2. Experimental Apparatus and Conditions

The schematic of the ignition and combustion rig of lignite particles used in the current study is shown in Figure 9. The visual drop tube furnace (VDTF) was composed of a reactor, a furnace, a feeding system, an air supply system, a smoke exhaust, and a dust removal system. The reactor was a vertical quartz reactor with an inner diameter of 50 mm and a length of 1000 mm. The reactor was evenly heated by the surrounding heating wires to ensure the uniform distribution of temperature. The effective reaction area of pulverized coal particles was 650 mm from the outlet of the feeder to the upper end of the lower water cooler. A fluidized-bed coal feeder was used to feed the samples to the reactor through a water-cooled injector at a rate of 0.1 g/min with a flow rate of 200 mL/min when the furnace temperature was 1300 K. At this temperature, the highest heating rate of particles was estimated to be 104 K/s.15 The difference between the set and measured temperature was within 2%. The fluidization feed method guaranteed the high discrete of particles in VDTF. A high-speed camera with a shutter rate of 1300 FPS/s and visual resolution of 1280 × 1024 pixels was used to record the combustion of coal particles through 30 mm × 600 mm observation windows.

Figure 9.

Schematic of the visual drop tube combustion experimental rig.

4.3. Ignition Model of Single Coal Particle with Moisture

4.3.1. Model Development

An ignition model of a single coal particle with moisture was used to obtain the parameters of the combustion process and determine the dominant mechanism of moisture on the ignition and combustion characteristics. The illustration of the proposed ignition model is shown in Figure 10. The model assumed that a radiation cloud composed of volatile components, soot, and bulk gas uniformly surrounded the particle, which was rapidly heated during volatile combustion and transferred heat to particle surfaces in the form of radiation. The heat of volatile combustion depended on the pyrolysis components, which was obtained from the CPD model. The temperature of the radiation cloud was between the ambient temperature and the volatile flame temperature, and it is calculated by eq 9.

Figure 10.

Illustration of a burning coal particle.

The ignition model of a single coal particle with moisture included the following assumptions:

The particle started to release moisture after entering the furnace, and the evaporation of moisture, devolatilization, and char oxidation were allowed to occur simultaneously in this study.

This model only considered the impact of moisture removal on the physical characteristics of the combustion of particles and did not consider the impact of the change of moisture content on the chemical characteristics.

The diameter of the particle did not change, and only the density of the particles changed during the processes of the release of moisture and devolatilization. The combustion of char resulted in a reduction in diameter.

The model did not consider the fragmentation of the particle during the combustion process.

The inside of the particle was considered to be isotropic, and the radiation cloud was composed of regular spheres.

4.3.2. Conservation Equations

The model of the single coal particle with moisture maintained energy and mass conservations during the simulation process.

Particle mass consisted of three parts: moisture, volatile matter, and char.

| 2 |

where mp is the mass of particles (kg), t is the time (s), mC is the mass of char (kg), mVM is the mass of volatile matter (kg), and mM is the mass of moisture (kg).

Energy balance was controlled by the rates of radiation and convection heat exchange between the ambient atmosphere and the particles, the internal heating process, the rate of heat loss of evaporation of moisture and devolatilization, and the rate of heat generation of char combustion, as given by eq 3.

| 3 |

where Q̇c is the rate of the heat of chemical reaction (J/s), Q̇cond is the rate of conduction heat from a particle’s surface to its core (J/s), Q̇conv is the convection heat rate of the particle and ambient atmosphere (J/s), Q̇rad is the radiation heat rate (J/s), Q̇M is the heat loss rate due to the evaporation of moisture (J/s), Q̇VM is the heat loss rate due to evaporation of devolatilization (J/s), TS is the surface temperature of the particle (K), and cp is the specific heat of the particle (J/kg/K).

The value of Q̇conv can be calculated using eq 4.

| 4 |

where Tg is the ambient gas temperature (K), dp is the particle diameter (m), h is the convection coefficient (W/m2/K) calculated using the correlation of Nuλ/dp, and λ is the conductivity coefficient of gas (W/m/K).

Particle internal thermal conductive process is calculated for the unsteady state and coupled with the Biot number Bi

| 5 |

here

| 6 |

The temperature of the particle’s core can be calculated using eq 7.

| 7 |

where TC is the center temperature of the particle (K), λp is the conduction coefficient of the particle (J/s/K/cm), and Bi is the ratio of the conductive resistance to convective resistance of the particle and has quite a small value (Bi < 0.1) for small dry particle (d < 200 μm). However, internal heat conduction has a more significant influence on the combustion process of the wet pulverized coal particle than that of the dry particles. Moreover, δ is the characteristic length of the sphere.

The rate of radiation heat transfer Q̇rad can be calculated without volatile combustion using eq 8.

| 8 |

| 9 |

where Tf is the radiant cloud temperature (K), hVM is the heat of volatile combustion14 (kJ/kg), df is the radius of radiant cloud, which is generally not more than 5 times the particle size23,24 (m), cp,f is the specific heat of combustion products (J/kg/K), and ρf is the density of combustion products (kg/m3).

The heat of volatile combustion can be calculated based on the pyrolysis component yield as predicted by the CPD model.

| 10 |

where mtar, mCH4, and mCO are the masses of tar, CH4, and CO produced during unit mass coal pyrolysis, respectively (g); and Qtar (37.5 kJ/g), QCH4 (10.1 kJ/g), and QCO (55.8kJ/g) are the calorific values of tar, CH4, and CO, respectively.

The rate of heat loss from the evaporation of moisture Q̇M can be calculated without volatile combustion using eq 11.

| 11 |

where ṙM is the rate of moisture evaporation (kg/s) and ΔhM is the heat loss due to the evaporation of moisture (kJ/kg), whereas ΔhM = 2400 kJ/kg.25

The heat loss rate of devolatilization Q̇VM is calculated using eq 12.

| 12 |

where ṙVM is the rate of volatile release (kg/s), Δh′VM is the heat of pyrolysis (kJ/kg), and Δh′VM = 420 kJ/kg.26

The heat generation from char’s combustion Q̇C is given by eq 13.

| 13 |

where ṙc is the rate of consumption of char (kg/s), ΔhC is the heat generation from char’s combustion, and ΔhC 21,000 kJ/kg.14

4.3.3. Moisture Evaporation model

The change in the mass of moisture over time is similar to that of volatile matter. The rate of evaporation of moisture is determined using eq 14.

| 14 |

where mM,0 and mM,i are the initial mass of moisture and the total mass of moisture before time i (kg), respectively.

4.3.4. Devolatilization Model

The chemical percolation devolatilization (CPD) model is a complex network model based on molecular structure. It has been reported to be useful in predicting the yield of volatile matter and product components during the rapid pyrolysis of coal. The model is more accurate than the simple kinetic devolatilization model.26,27 In the present study, the devolatilization model of the single coal particle with moisture can be determined by the data iteration of the CPD model and the ignition model. The heating rate of the particle from the ignition model under different conditions was put into the CPD model, and the CPD simulation results were fitted as the devolatilization correlation until the iterations converged. The devolatilization correlation is given by eq 15. Therefore, the devolatilization correlation was related to the moisture content and particle size. The determination method and the accuracy of the devolatilization correlation are described in detail in the previous work.14 The CPD model was also used to determine the total yield, volatile component yield, and heat of volatile chemical reaction (hVM) under various conditions.14 Some pyrolysis characteristic parameters from the CPD model are presented in Table 1. The correlation coefficient R2 of the volatile released curves from the ignition model and the CPD model was above 0.98, indicating that the fitting correlation can reflect the simulation results of the CPD model in a satisfactory way. Meanwhile, the volatile yield of the sample was 67.49% (daf) from the CPD model, which was substantially higher than that of 41.7% (daf) from the proximate analysis conversion. Similar results also appeared in some previous studies.28,29 Therefore, it can be said that the results of the CPD model can more accurately reflect the devolatilization process of coal.

| 15 |

where mvm,i is the total mass of volatile matter released before time i (kg), Tp,i is the average temperature of particles at time i, and Tp,i = (TS,i + TC,i)/2.

Table 1. Pyrolysis Characteristics of the Coal Particle (Particle Size of 125 μm).

| moisture content (wt %) | hVM (MJ/kg) | VM yield (wt %) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16.94 | 67.49 | 0.98631 |

| 5 | 16.80 | 67.06 | 0.99378 |

| 10 | 16.69 | 66.75 | 0.99436 |

| 20 | 15.96 | 64.54 | 0.98129 |

4.3.5. Char Combustion Model

The combustion of char was studied using the global kinetics model, which considers the mass transfer and oxygen diffusion into the pore structure of the particle, followed by chemical reactions on the pore walls.30 The rate of reaction of char in the global kinetics model was controlled by the rate of mass transfer and the apparent reaction rate and can be expressed using eq 16.

| 16 |

where SP is the specific surface area of the particle, SP = 18,000 (m2/kg), KC is the apparent reaction rate coefficient (kg/m2/s/atm), Km is the mass transfer coefficient (kg/m2/s/atm), and PO2,∞ is the partial pressure of oxygen in the bulk gas (atm).

The apparent reaction rate coefficient is given by eq 17.

| 17 |

where η is the effectiveness factor, γ is the characteristic size of the particle (m), ρp is the density of the particle (kg/m3), A0 is the frequency factor, A0 = 8.6 × 102 (kg/m2/s/atm), Ea is the activation energy, Ea = 150,000 (kJ/mol),31 and Ru is the gas constant with the value of 8.314 (J/K/mol).

The apparent reaction rate coefficient is given by eq 18.

|

18 |

where MC is the molecular weight of carbon, R is the gas constant with the value of 82.06 (cm3·atm/mol/K), Sh is the Sherwood number (Sh = 232,33), and Dref is the reference value of the diffusion coefficient.

4.3.6. Some Key Parameters

The diameter of the particle does not change during the release of moisture and volatile matter. However, the density of the particle changes during the process and is given by eq 19.

| 19 |

The diameter of the particle changes during the combustion of char, as shown in eq 20.

| 20 |

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22078141), the Education Department Funding Program of Liaoning Province (LJKZ0290), the Education Department Excellent Talents Training Program of Liaoning Province (2020LNQN21), and the Excellent Talents Training Program of University of Science and Technology Liaoning (2019RC12).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Cheng Y.; Pan Z. Reservoir properties of Chinese tectonic coal: A review. Fuel 2020, 260, 116350 10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.; You C. Effect of Upgraded Lignite Product Water Content on The Propensity for Spontaneous Ignition. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 20–26. 10.1021/ef301771r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M.; Zheng J.; Liu X. Effect of Hydrothermal Dehydration on the Slurry Ability of Lignite. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 12027–12035. 10.1021/acsomega.1c00639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Li Y.; Song Q.; Liu S.; Li M.; Shu X. Catalytic reforming of volatiles from co-pyrolysis of lignite blended with corn straw over three iron ores: Effect of iron ore types on the product distribution, carbon-deposited iron ore reactivity and its mechanism. Fuel 2021, 286, 119398 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Song Q.; Liu S.; Li Y.; Wang X.; Shu X. Study on catalytic co-pyrolysis of physical mixture/staged pyrolysis characteristics of lignite and straw over an catalytic beds of char and its mechanism. Energy Convers. Manage. 2018, 161, 13–26. 10.1016/j.enconman.2018.01.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engin B.; Atakül H.; Ünlü A.; Olgun Z. CFB combustion of low-grade lignites: Operating stability and emissions. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 542–553. 10.1016/j.joei.2018.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allardice D. J.; Clemow L. M.; Favas G.; Jackson W. R.; Marshall M.; Sakurovs R. The characterisation of different forms of moisture in low rank coals and some hydrothermally dried products. Fuel 2003, 82, 661–667. 10.1016/S0016-2361(02)00339-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.; Xu G.; Zhao S.; Zhou L.; Yang Y.; Zhang D. An improved configuration of lignite pre-drying using a supplementary steam cycle in a lignite fired supercritical power plant. Appl. Energy 2015, 160, 882–891. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.01.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai X.; Ge H.; Wang T.; Shu C.; Li J. Effect of water immersion on active functional groups and characteristic temperatures of bituminous coal. Energy 2020, 205, 118076 10.1016/j.energy.2020.118076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tahmasebi A.; Zheng H.; Yu J. The Influences of Moisture on Particle Ignition Behavior of Chinese and Indonesian Lignite Coals in Hot Air Flow. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 153, 149–155. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2016.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens A. H.; Matheson T. W. The role of moisture in the self-heating of low-rank coals. Fuel 1996, 75, 891–895. 10.1016/0016-2361(96)00010-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prationo W.; Zhang J.; Cui J.; Wang Y.; Zhang L. Influence of inherent moisture on the ignition and combustion of wet Victorian brown coal in air-firing and oxy-fuel modes: Part 1: The volatile ignition and flame propagation. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 138, 670–679. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2015.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R. G.; Li D.; Jeon C. H. Experimental investigation of ignition behavior for coal rank using a flat flame burner at a high heating rate. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2014, 54, 212–218. 10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2013.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Tahmasebi A.; Dou J.; Khoshk Rish J. S.; Tian L.; Yu J. Mechanistic Investigations of Particle Ignition of Pulverized Coals: An Enhanced Numerical Model and Experimental Observations. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 16666–16678. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c03093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães D.; Kazanç F.; Ferreira A.; Rabaçal M.; Costa M. Ignition behavior of Turkish biomass and lignite fuels at low and high heating rates. Fuel 2017, 207, 154–164. 10.1016/j.fuel.2017.06.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khatami R.; Stivers C.; Joshi K.; Levendis Y. A.; Sarofim A. F. Combustion behavior of single particles from three different coal ranks and from sugar cane bagasse in O2 /N2 and O2 /CO2 atmospheres. Combust. Flame 2012, 159, 1253–1271. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2011.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarroza A. C.; Bennet T. D.; Eastwick C.; Liu H. Characterising pulverized fuel ignition in a visual drop tube furnace by use of a high-speed imaging technique. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 157, 565–576. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2016.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z.; Zhang T.; Zheng S.; Wu W.; Zhou Y. Ignition and combustion characteristics of coal particles under high-temperature and low-oxygen environments mimicking MILD oxy-coal combustion condition. Fuel 2019, 253, 1104–1113. 10.1016/j.fuel.2019.05.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y.; Li S.; Li G.; Wu N.; Yao Q. The transition of heterogeneouse-homogeneous ignitions of dispersed coal particle streams. Combust. Flame 2014, 161, 2458–2468. [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.; Fan L.; Fan J.; Zhong F. Effect of water content on the induced alteration of pore morphology and gas sorption/diffusion kinetics in coal with ultrasound treatment. Fuel 2021, 306, 121752 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Q.; Chen T.; Tang C.; Sedighi M.; Wang S.; Huang Q. Influence of moisture on crack propagation in coal and its failure modes. Eng. Geol. 2019, 258, 105156 10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.105156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Tahmasebi A.; Dou J.; Lee S.; Li L.; Yu J. Influence of functional group structures on combustion behavior of pulverized coal particles. J. Energy Inst. 2020, 93, 2124–2132. 10.1016/j.joei.2020.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez S.; Gonzalo-Tirado C. Properties and relevance of the volatile flame of an isolated coal particle in conventional and oxy-fuel combustion conditions. Combust. Flame 2017, 176, 94–103. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2016.09.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goshayeshi B.; Sutherland J. C. A comparison of various models in predicting ignition delay in single-particle coal combustion. Combust. Flame 2014, 161, 1900–1910. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2014.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeasmin H.; Mathews J. F.; Ouyang S. Rapid Devolatilisation of Yallourn Brown Coal at High Pressures and Temperatures. Fuel 1999, 78, 11–24. 10.1016/S0016-2361(98)00119-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards A. P.; Fletcher T. H. A comparison of simple global kinetic models for coal devolatilization with the CPD model. Fuel 2016, 185, 171–180. 10.1016/j.fuel.2016.07.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant D. M.; Pugmire R. J.; Fletcher T. H.; Kerstein A. R. Chemical Model of Coal Devolatilization Using Percolation Lattice Statistics. Energy Fuels 1989, 3, 175–186. 10.1021/ef00014a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rieth M.; Clements A. G.; Rabaçal M.; Proch F.; Stein O. T.; Kempf A. M. Flamelet LES modeling of coal combustion with detailed devolatilization by directly coupled CPD. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2017, 36, 2181–2189. 10.1016/j.proci.2016.06.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed S.; Sharma A.; Pareek V.; Wu H.; Yu Y. A review on biomass pyrolysis models: Kinetic, network and mechanistic models. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 123, 104–122. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2019.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tahmasebi A.; Yu J.; Han Y.; Zhao H.; Bhattacharya S. A kinetic study of microwave and fluidized-bed drying of a Chinese lignite. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2014, 92, 54–65. 10.1016/j.cherd.2013.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cen K.Advanced Combustion, 1st ed.; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, 2002; pp 308–309. [Google Scholar]

- Smith I. W. The combustion rates of coal chars: A review. Symp. Combust. 1982, 19, 1045–1065. 10.1016/S0082-0784(82)80281-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R. G.; Jeon C. H. Intrinsic reaction kinetics of coal char combustion by direct measurement of ignition temperature. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 63, 565–576. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2013.11.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]