Abstract

The hexameric AAA‐ATPase valosin‐containing protein (VCP) is essential for mitochondrial protein quality control. How VCP is recruited to mammalian mitochondria remains obscure. Here we report that UBXD8, an ER‐ and lipid droplet‐localized VCP adaptor, also localizes to mitochondria and locally recruits VCP. UBXD8 associates with mitochondrial and ER ubiquitin E3 ligases and targets their substrates for degradation. Remarkably, both mitochondria‐ and ER‐localized UBXD8 can degrade mitochondrial and ER substrates in cis and in trans. UBXD8 also associates with the TOM complex but is dispensable for translocation‐associated degradation. UBXD8 knockout impairs the degradation of the pro‐survival protein Mcl1 but surprisingly sensitizes cells to apoptosis and mitochondrial stresses. UBXD8 knockout also hyperactivates mitophagy. We identify pro‐apoptotic BH3‐only proteins Noxa, Bik, and Bnip3 as novel UBXD8 substrates and determine that UBXD8 inhibits apoptosis via degrading Noxa and restrains mitophagy via degrading Bnip3. Collectively, our characterizations reveal UBXD8 as the major mitochondrial adaptor of VCP and unveil its role in apoptosis and mitophagy regulation.

Keywords: apoptosis, mitochondria‐associated degradation, mitophagy, UBXD8, VCP

Subject Categories: Autophagy & Cell Death, Organelles, Post-translational Modifications & Proteolysis

UBXD8 is a mammalian VCP adaptor that dually localizes to mitochondria and the ER to mediate mitochondria‐ and ER‐associated protein degradation. UBXD8 facilitates the degradation of mitochondrial substrates to restrain apoptosis and mitophagy.

Introduction

Mitochondria‐associated degradation (MAD) ubiquitinates mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) proteins and targets them to proteasome for degradation (Karbowski & Youle, 2011; Zheng et al, 2019; Song et al, 2021). MAD critically regulates mitochondrial quality control and function. In yeast, Doa1‐mediated MAD regulates ER‐mitochondria tethering and antagonizes mitochondrial oxidative stress and cell death (Wu et al, 2016; Saladi et al, 2020). In Drosophila, ubiquitin E3 ligases Parkin and MUL1 ubiquitinate and degrade mitofusin to prevent mitochondrial hyperfusion and muscle degeneration (Ziviani et al, 2010; Yun et al, 2014). In mammalian cells, stress‐induced degradation of Mcl1 initiates apoptosis (Zhong et al, 2005; Inuzuka et al, 2011; Wertz et al, 2011). Parkin‐mediated degradation of mitofusin (Tanaka et al, 2010) and MARCH5‐mediated degradation of FUNDC1 (Chen et al, 2017) regulate mitophagy.

A key component of MAD is the hexameric AAA‐ATPase VCP (Cdc48 in yeast), which hydrolyzes ATP to dislocate ubiquitinated MOM proteins out of membrane and transfers them to the proteasome (Karbowski & Youle, 2011; Zheng et al, 2019). VCP mutations cause inclusion body myopathy, Paget's disease of the bone, and frontotemporal dementia (IBMPFD) as well as familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (fALS) in human (Watts et al, 2004; Johnson et al, 2010). Mitochondrial damage and functional impairment are prominent in VCP‐mutant organisms including yeast, drosophila, mouse, and human (Braun et al, 2006; Custer et al, 2010; Chang et al, 2011; Yin et al, 2012; Bartolome et al, 2013; Kim et al, 2013; Ludtmann et al, 2017; Zhang et al, 2017).

VCP is an ATP‐dependent unfoldase that has thousands of clients; it is assisted by an array of cofactors to recruit different substrates (van den Boom & Meyer, 2018). In yeast, Doa1 is a soluble Cdc48 adaptor that specifically recognizes ubiquitinated MOM proteins and targets them for degradation (Wu et al, 2016; Saladi et al, 2020). Ubx2 is initially identified as an ER‐localized Cdc48 cofactor that mediates ER‐associated degradation (ERAD) in yeast (Neuber et al, 2005; Schuberth & Buchberger, 2005). Recently, it was reported that Ubx2 also localizes to mitochondria and associates with the TOM complex. TOM‐associated Ubx2 recruits Cdc48 to remove stalled precursor proteins, a process named translocation‐associated degradation (Martensson et al, 2019).

In contrast to yeast, the mitochondrial VCP adaptor in mammalian cells remains poorly characterized. Here we identify UBXD8 as the major mitochondrial adaptor of VCP. We have analyzed the complex formation and characterized the substrates of UBXD8. Our study mechanistically links UBXD8 to apoptosis and mitophagy regulation in mammalian cells.

Results

UBXD8 dually localizes to mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum

In ongoing projects in the lab, we have purified ubiquitinated proteins from the mitochondrial fraction and determined protein identity by mass spectrometry. Interestingly, UBXD8 is enriched in our mass spectrometry results (unpublished results). UBXD8 contains an N‐terminal UBA domain to interact with ubiquitinated proteins, a hairpin domain to associate with membrane, a UAS domain, and a C‐terminal UBX domain to associate with VCP (Fig 1A). UBXD8 is a VCP adaptor that localizes to the ER and lipid droplets, where it assembles with ubiquitin E3 ligase complexes to mediate ER‐ and lipid droplet‐associated degradation (Mueller et al, 2008; Lee et al, 2010; Christianson et al, 2011; Suzuki et al, 2012; Olzmann et al, 2013; Schrul & Kopito, 2016). We thus decided to examine UBXD8 localization.

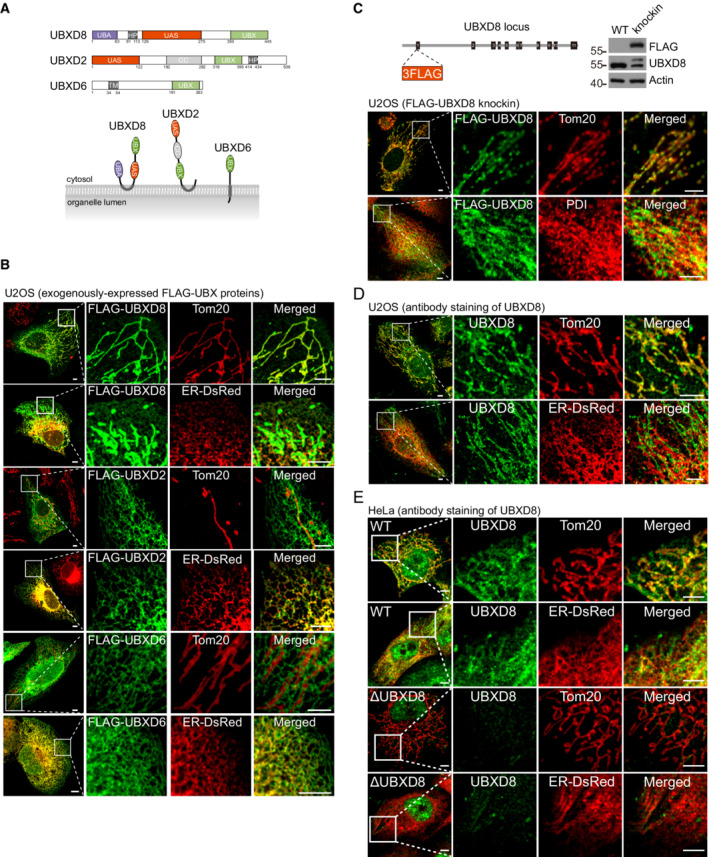

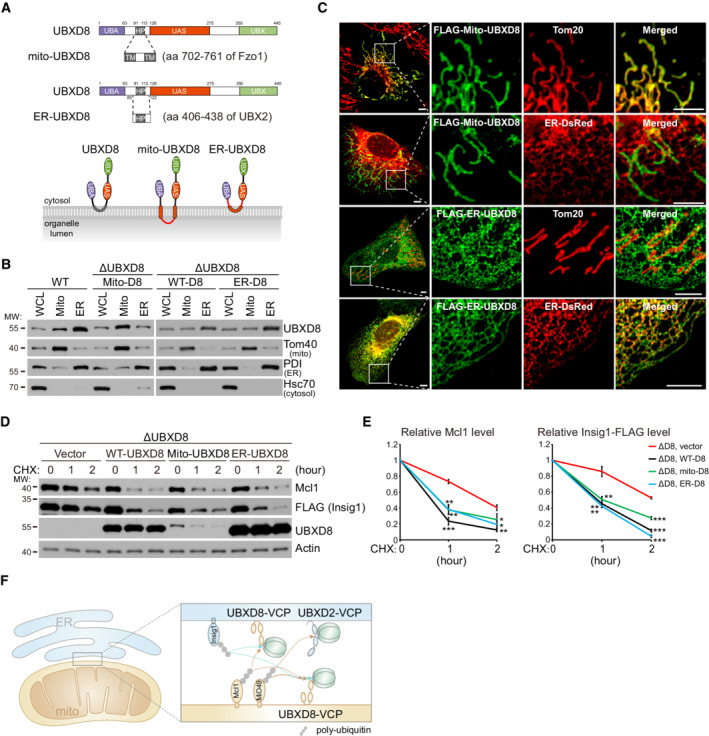

Figure 1. UBXD8 dually localizes to mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

-

ASchematic of the domain structure and membrane topology of UBXD8, UBXD2, and UBXD6. UBA, ubiquitin‐associated; HP, hairpin; UAS, ubiquitin associating; UBX, Ubiquitin regulatory X; CC, coiled‐coil.

-

BImmunofluorescence analysis of exogenously expressed FLAG‐UBXD8, FLAG‐UBXD2, and FLAG‐UBXD6 in U2OS cells. Scale bar, 5 μm.

-

CSchematic, western blot, and immunofluorescence analysis of the 3 × FLAG‐UBXD8 knockin U2OS cell line. Scale bar, 5 μm.

-

DImmunofluorescence analysis of endogenous UBXD8 in U2OS cells. Scale bar, 5 μm.

-

EImmunofluorescence analysis of endogenous UBXD8 in WT and ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Data information: In (B–E), mitochondria were visualized by anti‐Tom20 immunostaining; ER was labeled by ER‐DsRed or by anti‐PDI immunostaining.

Three VCP adaptors contain a hairpin domain or a transmembrane segment to associate with membranes: UBXD8, UBXD2 (Liang et al, 2006), and UBXD6 (Madsen et al, 2011; Fig 1A). These proteins were N‐terminally tagged with a FLAG tag and overexpressed in U2OS cells. FLAG‐UBXD8 localized strongly to mitochondria and weakly to the ER as shown by immunofluorescence analysis (Fig 1B). In contrast, FLAG‐UBXD2 and FLAG‐UBXD6 exclusively localized to the ER (Fig 1B). We further generated a FLAG‐UBXD8 knockin clone in U2OS cells. Immunofluorescence analysis showed that endogenously tagged UBXD8 also dominantly localizes to mitochondria (Fig 1C). Previously, the dominant ER and lipid droplet localization of UBXD8 was determined by immunofluorescence staining with a home‐made polyclonal antibody (Mueller et al, 2008; Olzmann et al, 2013) or with commercial polyclonal antibodies (16251‐AP, Proteintech, (Schrul & Kopito, 2016); Goat anti‐ETEA/UBXD8, Santa Cruz, (Suzuki et al, 2012)). The staining patterns of these antibodies were not verified by UBXD8 knockout. We obtained a monoclonal UBXD8 antibody (#34945, CST) for immunofluorescence staining. Endogenous UBXD8 had strong mitochondrial localization in both U2OS and HeLa cells (Fig 1D and E). UBXD8 localized to the ER more apparently in HeLa cells than in U2OS cells (Fig 1D and E). Importantly, the specificity of the antibody was confirmed by UBXD8 knockout (ΔUBXD8) in HeLa cells (Fig 1E). Therefore, endogenous UBXD8 does localize to mitochondria.

UBXD8 associates with the TOM complex but is dispensable for translocation‐associated degradation

While this work was ongoing, a paper reported that Ubx2, the yeast homolog of UBXD8, associates with the TOM complex to mediate translocation‐associated degradation (Martensson et al, 2019). We purified mitochondrial fractions from HeLa cells and lysed them with buffer containing 1% digitonin to preserve membrane protein complexes. Under this condition, FLAG‐UBXD8 pulled down VCP and the TOM complex components Tom40, Tom70, and Tom22 (Fig EV1A). FLAG‐UBXD8‐UBX*, which carries four point mutations (K367A, F407A, P408G, R409A) in the UBX domain to disrupt the UBXD8–VCP interaction (Dreveny et al, 2004), did not pull down VCP but still immunoprecipitated the TOM complex (Fig EV1A), suggesting the interaction is independent of VCP binding.

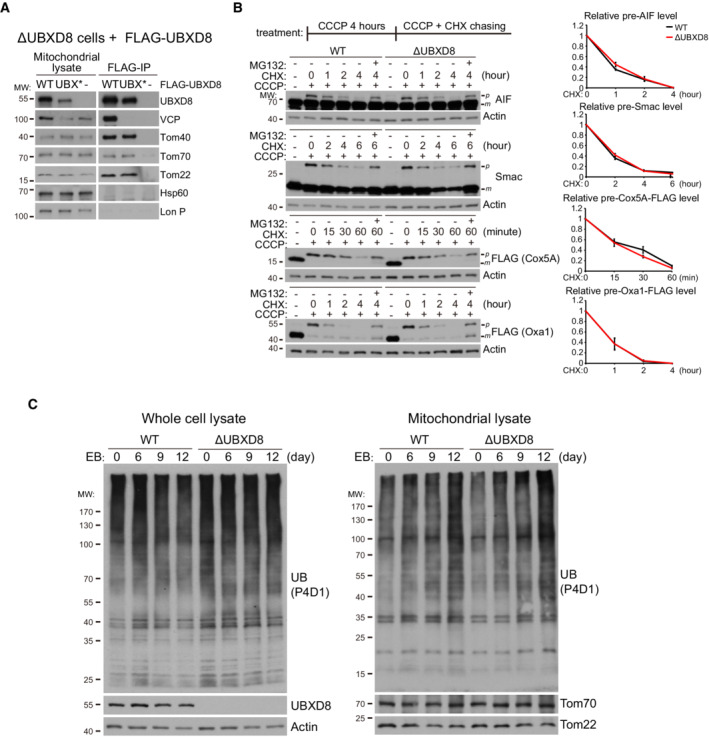

Figure EV1. UBXD8 associates with the TOM complex but is dispensable for translocation‐associated degradation. Related to Fig 2 .

- Immunoprecipitation analysis of the interaction between UBXD8 and the TOM complex. Mitochondrial fractions were purified from the indicated HeLa cells and lysed with lysis buffer containing 1% digitonin. Mitochondrial lysates were then subjected to anti‐FLAG immunoprecipitation.

- Western blot and quantitative analysis of translocation‐associated degradation with four model substrates: AIF, Smac, Cox5A‐FLAG, and Oxa1‐FLAG. WT and ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells were treated with 15 μM CCCP for 4 h and then subjected to CCCP + CHX (200 μg/ml) chasing for the indicated time. Cox5A‐FLAG and Oxa1‐FLAG expression were induced by Doxycycline (1 μg/ml) for 4 h. MG132: 20 μM. Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats.

- Western blot analysis of mitochondrial ubiquitination induced by mtDNA depletion (EB treatment) in WT and ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells. Cells were treated with EB (50 ng/ml) plus uridine (50 μg/ml), pyruvate (1 mM), and glutamine (2 mM) for the indicated time. Whole cell lysates and mitochondrial fraction lysates were analyzed.

Source data are available online for this figure.

To examine if UBXD8 facilitates translocation‐associated degradation, we treated WT and ΔUBXD8 cells with carbonyl cyanide m‐chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) to depolarize mitochondria and arrest precursor import. We identified four mitochondrial proteins with clear precursor accumulation on CCCP treatment: AIF, Smac, and exogenously expressed Cox5A‐FLAG and Oxa1‐FLAG (Fig EV1B). The precursors of these proteins accumulated to similar levels in both WT and ΔUBXD8 cells on 4 h of CCCP treatment and were degraded in similar kinetics upon CCCP plus CHX treatment (Fig EV1B).

In case acute CCCP treatment is too harsh and has caused the rapid overaccumulation of precursors that are beyond the capacity of UBXD8 to remove, we gradually depolarized mitochondria by depleting mtDNA with ethidium bromide (EB). Ubiquitin signals significantly accumulated in mitochondrial fractions after 12 days of EB treatment, but no difference was observed between WT and ΔUBXD8 cells (Fig EV1C). Therefore, UBXD8 seems not essential for translocation‐associated degradation in mammalian cells.

UBXD8 forms complexes with mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum ubiquitin E3 ligases and recruits valosin‐containing protein to mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum

To examine the protein complex formation of UBXD8, we purified mitochondrial fraction from HeLa cells and performed a blue native gel analysis. The specificity of UBXD8 signal was confirmed by UBXD8 knockout (Fig 2A). UBXD8 distributed in a wide molecular range from 200 to 1,236 KD (Fig 2A), indicating UBXD8 may form complex with diverse machineries. To examined if UBXD8 associates with mitochondrial and ER ubiquitin E3 ligases, we overexpressed two mitochondrial ubiquitin E3 ligases 3HA‐MARCH5 (Karbowski et al, 2007) and 3HA‐MUL1 (Li et al, 2008), as well as an ER ubiquitin E3 ligase 3HA‐RNF185 (El Khouri et al, 2013). Anti‐HA immunoprecipitation showed that all the ubiquitin E3 ligases pulled down endogenous UBXD8, particularly under MG132 (proteasome inhibitor) treatment, but none of them pulled down UBXD2 (Fig 2B). We further generated a FLAG‐UBXD8 knockin HEK293T cell line and performed anti‐FLAG immunoprecipitation. FLAG‐UBXD8 pulled down endogenous MARCH5 and RNF185 (Fig 2C). These results demonstrate that UBXD8 associates with mitochondrial and ER ubiquitin E3 ligases.

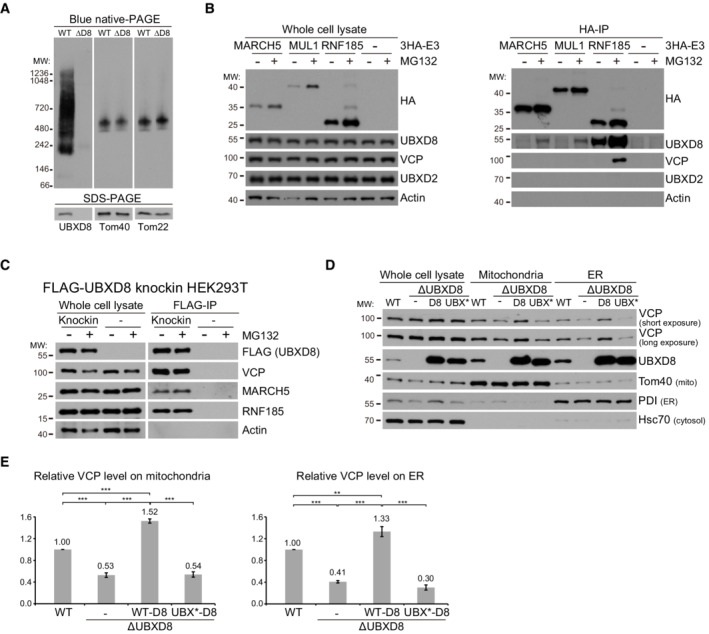

Figure 2. UBXD8 associates with mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) ubiquitin E3 ligases and recruits VCP to mitochondria and the ER.

-

ABlue native gel analysis of UBXD8 in mitochondrial fractions purified from WT and ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells.

-

BImmunoprecipitation analysis of UBXD8 interaction with mitochondrial (MARCH5 and MUL1) and ER (RNF185) ubiquitin E3 ligases. HeLa cells were infected with lentivirus to stably express HA‐tagged ubiquitin E3 ligases. Whole cell lysates were prepared for anti‐HA immunoprecipitation.

-

CImmunoprecipitation analysis of UBXD8 interaction with MARCH5 and RNF185. Whole cell lysates from 3 × FLAG‐UBXD8 knockin HEK293T cells were prepared for anti‐FLAG immunoprecipitation. MARCH5 and RNF185: short exposure for whole cell lysate blots, long exposure for FLAG‐IP blots.

-

DFractionation analysis of UBXD8's effect on VCP recruitment to mitochondria and the ER. Whole cell lysate, mitochondria, and ER fractions were purified (see Materials and Methods for detail) from WT, ΔUBXD8, and ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells rescued with UBXD8 or the UBX* mutant. UBX*‐UBXD8 carries four point mutations (K367A, F407A, P408G, R409A) in the UBX domain to disrupt the UBXD8‐VCP interaction. For each sample, 5 μg proteins were loaded for western blot analysis.

-

EQuantitative analysis of VCP levels in the mitochondria and ER fractions from the indicated HeLa cells. Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats. Statistics: one‐way ANOVA; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To examine if UBXD8 recruits VCP to mitochondria and the ER, we purified the mitochondria‐enriched and ER‐enriched fractions (Fig 2D). UBXD8 knockout did not affect cellular VCP level but significantly reduced mitochondrial and ER VCP levels (Fig 2D and E). We then rescued ΔUBXD8 cells with wild‐type (WT) UBXD8 or the UBX* mutant. Both WT and mutant UBXD8 were expressed at much higher levels than endogenous UBXD8. Overexpression of WT UBXD8 significantly increased mitochondrial and ER VCP levels, whereas overexpression of the UBX* mutant had no such effect (Fig 2D and E). Thus, UBXD8 mediates VCP recruitment to mitochondria and the ER.

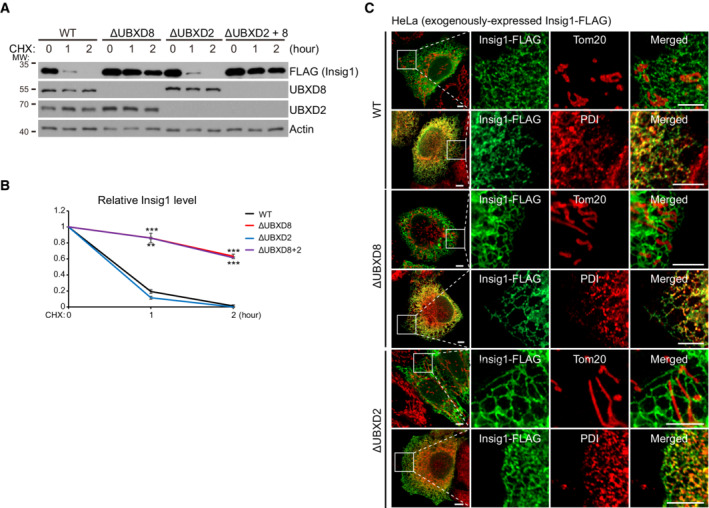

Both UBXD8 and UBXD2 (endoplasmic reticulum valosin‐containing protein adaptor) participate in mitochondrial protein degradation

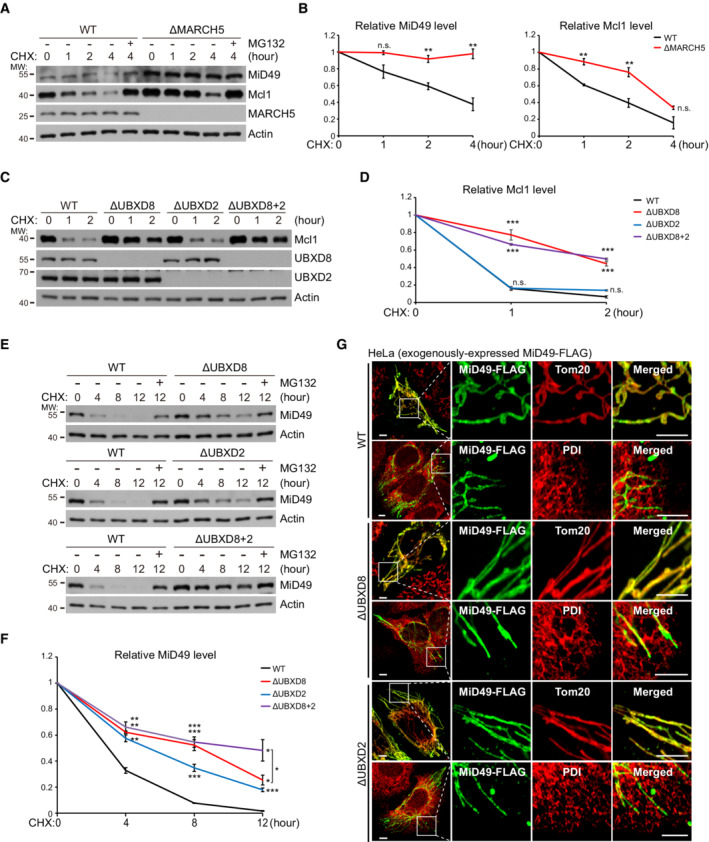

MiD49 and Mcl1 are two substrates of MARCH5 (Xu et al, 2016; Cherok et al, 2017). Both proteins accumulated in ΔMARCH5 HeLa cells (Fig 3A). MARCH5 knockout almost completely blocked MiD49 degradation but only partially delayed Mcl1 degradation as demonstrated by the cycloheximide (CHX, protein synthesis inhibitor) chasing experiment (Fig 3A and B). This is because multiple ubiquitin E3 ligases are involved in Mcl1 degradation (Zhong et al, 2005; Inuzuka et al, 2011; Wertz et al, 2011). UBXD8 knockout in HeLa cells delayed Mcl1 degradation (Fig 3C and D). As a control, UBXD2 knockout in both WT and ΔUBXD8 cells did not affect Mcl1 degradation (Fig 3C and D). But to our surprise, MiD49 degradation was delayed by the knockout of either UBXD8 or UBXD2 and was further delayed by the knockout of both proteins (Fig 3E and F). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that MiD49 maintained mitochondrial localization in ΔUBXD8 and ΔUBXD2 cells (Fig 3G), suggesting that ER‐localized UBXD2 degrades mitochondrial MiD49 in trans. Because MiD49 localizes to the mitochondria‐ER contract sites to mediate mitochondrial fission (Elgass et al, 2015), the proximity between mitochondria and the ER at the contact sites may facilitate MiD49 degradation by UBXD2. Taken together, both mitochondrial and ER VCP adaptors participate in mitochondrial protein degradation.

Figure 3. Both UBXD8 and UBXD2 (ER VCP adaptor) participate in mitochondrial protein degradation.

-

A, BWestern blot (A) and quantitative (B) analyses of MiD49 and Mcl1 degradation in WT and ΔMARCH5 HeLa cells. Cycloheximide (CHX: 200 μg/ml; protein synthesis inhibitor); MG132: 20 μM, proteasome inhibitor.

-

C, DWestern blot (C) and quantitative (D) analyses of Mcl1 degradation in the indicated HeLa cells.

-

E, FWestern blot (E) and quantitative (F) analyses of MiD49 degradation in the indicated HeLa cells.

-

GImmunofluorescence analysis of MiD49‐FLAG localization in the indicated HeLa cells. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Data information: Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats (B, D, F). Statistics: two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test (B, D, F); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n.s., not significant.

UBXD8 degrades mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum substrates in cis and in trans

Stimulated by the unexpected working mode of UBXD2, we investigated whether UBXD8 can degrade substrates in cis and in trans as UBXD2. We replaced the hairpin domain of UBXD8 by the mitochondrial targeting sequence of yeast Fzo1 (aa 702–761, codon‐optimized) to generate mitochondrial UBXD8 (mito‐UBXD8), and replaced the harpin domain and its flanking sequences of UBXD8 by that of UBXD2 to generate ER‐UBXD8 (Fig 4A). Fractionation experiments showed that mito‐UBXD8 has enhanced mitochondrial localization and ER‐UBXD8 has enhanced ER localization as compared with WT UBXD8 (Fig 4B). However, because of the extensive mitochondria‐ER tethering (Phillips & Voeltz, 2016), we could not completely separate mitochondria and ER by fractionation. We thus performed immunofluorescence analysis and found that FLAG‐mito‐UBXD8 exclusively localized to mitochondria and FLAG‐ER‐UBXD8 exclusively localized to the ER (Fig 4C).

Figure 4. UBXD8 degrades mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) substrates in cis and in trans .

-

ASchematic of mito‐UBXD8 and ER‐UBXD8.

-

BFractionation analysis of the subcellular localization of mito‐UBXD8 and ER‐UBXD8. Whole cell lysate, mitochondria, and ER fractions were purified from the indicated HeLa cells. Exogenously expressed mito‐UBXD8 has similar expression level with endogenous UBXD8 in WT cells; exogenously expressed WT UBXD8 and ER‐UBXD8 have similar expression levels.

-

CImmunofluorescence analysis of mito‐UBXD8 and ER‐UBXD8 localization in U2OS cells. Scale bar, 5 μm.

-

D, EWestern blot (D) and quantitative (E) analyses of Mcl1 degradation in the indicated HeLa cells. ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells were rescued with vector, WT‐, mito‐, and ER‐UBXD8. Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats (E). Statistics: two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test (E); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

-

FCartoon illustration of the substrate degradation by mitochondrial and ER adaptor‐VCP complexes.

Insig1 is an ER‐localized UBXD8 substrate (Lee et al, 2008). UBXD8 knockout blocked the degradation of Insig1‐FLAG (Fig EV2A and B). Insig1‐FLAG localized to the ER in both WT and ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells as shown by immunofluorescence analysis (Fig EV2C). Interestingly, both mito‐UBXD8 and ER‐UBXD8 restored the degradation of Mcl1 (mitochondrial UBXD8 substrate) and Insig1‐FLAG (ER UBXD8 substrate) in ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells (Fig 4D and E). Collectively, these results establish that mitochondrial and ER VCP adaptors can work in cis or in trans to degrade their substrates (Fig 4F).

Figure EV2. The degradation and subcellular localization of Insig1‐FLAG. Related to Fig 4 .

-

A, BWestern blot (A) and quantitative analysis (B) of Insig1‐FLAG degradation in the indicated HeLa cells. Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats (B). Statistics: two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test (B); ***P < 0.001.

-

CImmunofluorescence analysis of Insig1‐FLAG localization in the indicated HeLa cells. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Source data are available online for this figure.

UBXD8 knockout sensitize cells to mitochondrial stresses and apoptotic insults

To understand the mitochondrial function of UBXD8, we challenged cells with multiple mitochondrial stressors. ΔUBXD8 cells grew normally as WT cells under DMSO treatment, but showed strong growth inhibition under oligomycin (complex V inhibitor) or chloramphenicol (mitochondrial translation inhibitor) treatment; this phenotype was rescued by UBXD8 re‐expression (Fig 5A and B). ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells also showed severe growth inhibition and cell death upon mtDNA depletion (EB treatment; Fig 5C). UBXD8 overexpression in ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells not only rescued these defects but also enhanced cell proliferation under EB treatment (Fig 5C). Thus, UBXD8 protects cells against mitochondrial stresses.

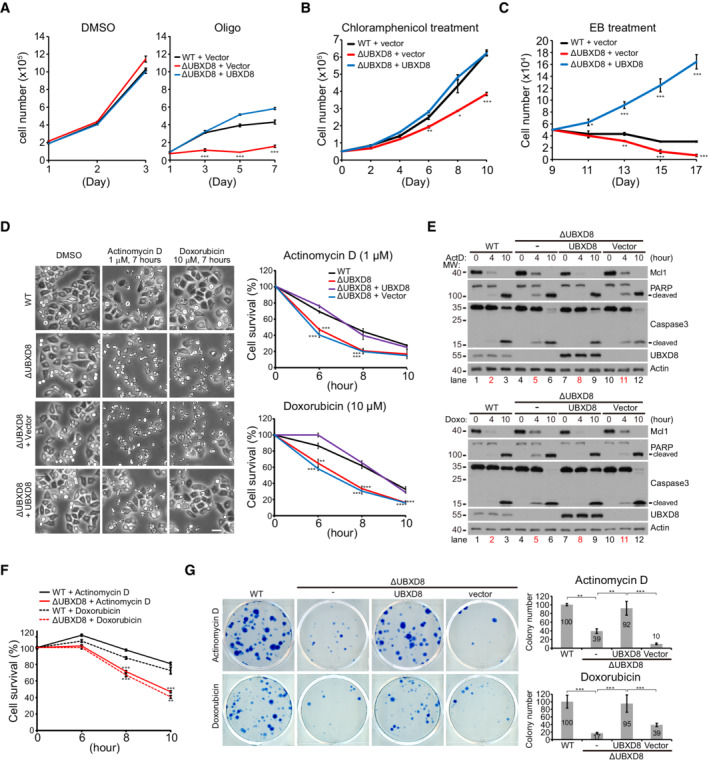

Figure 5. UBXD8 knockout sensitizes cells to mitochondrial stresses and apoptotic insults.

-

A–CGrowth tests of the indicated HeLa cells in response to oligomycin (A), chloramphenicol (B), and ethidium bromide (EB) (C) treatment. Oligo: 10 μM; Chloramphenicol: 300 μg/ml; EB: 50 ng/ml.

-

DCell survival analysis of the indicated HeLa cells treated with actinomycin D (ActD, 1 μM) or doxorubicin (Doxo, 10 μM). Representative images are shown. Cell viability was measured by Cell Titer‐Glo. Scale bar, 50 μm.

-

EWestern blot analysis of apoptosis activation (caspase cleavage and PARP cleavage) in the indicated HeLa cells treated similarly as in (D).

-

FCell survival analysis of WT and ΔUBXD8 MCF7 cells treated with ActD (1 μM) or Doxo (10 μM). Cell viability was measured by Cell Titer‐Glo.

-

GCell survival analysis of the indicated HeLa cells. 7 × 105 cells in one well of 6‐well plate were treated with ActD (200 nM) for 4 h or Doxo (50 nM) for 2 h and subsequently cultured in normal medium for 21 days. Surviving colonies were stained by 0.1% (W/V) methylene blue. Representative images and quantifications of the surviving colony numbers are shown.

Data information: Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats (A, B, C, D, F, G). Statistics: two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test (A, B, C, D, F); one‐way ANOVA (G); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

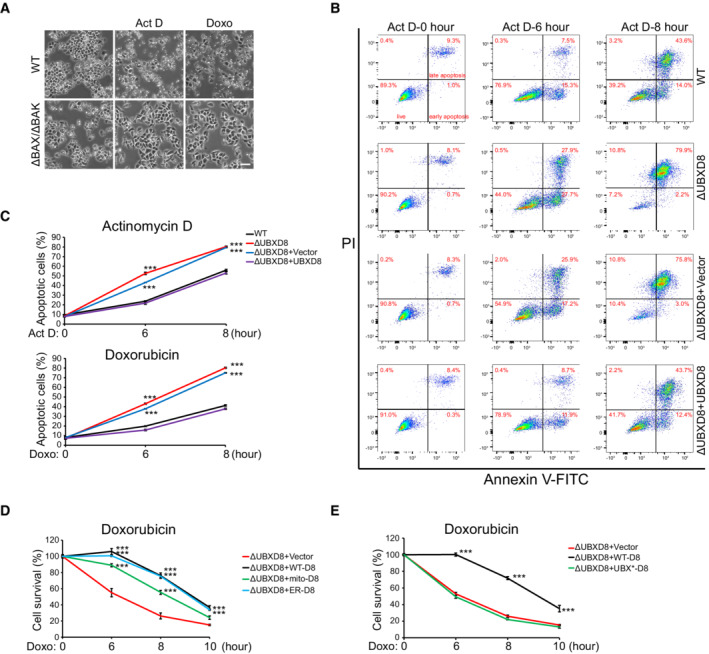

Because UBXD8 knockout delays Mcl1 degradation, we wondered if ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells are resistant to apoptosis. However, two chemotherapeutic drugs, doxorubicin (Doxo) and actinomycin D (ActD), induced faster and stronger cell death in ΔUBXD8 cells (Fig 5D). The cell death is apoptosis because ΔBAX ΔBAK HeLa cells showed complete resistance to these two drugs (Fig EV3A). Western blot analysis showed that both drugs induced stronger caspase‐3 activation and PARP cleavage in ΔUBXD8 cells (Fig 5E), indicating excessive apoptosis. FACS analysis of phosphatidylserine externalization (annexin‐V‐FITC staining, early apoptosis marker) and plasma membrane breakage (PI staining, later apoptosis marker) confirmed that ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells had enhanced apoptosis upon Doxo or ActD treatment (Fig EV3B and C). The enhanced apoptosis in ΔUBXD8 cells was rescued by WT, mito‐, and ER‐UBXD8 (Figs 5D and E, and EV3D) but not by the UBX* mutant (Fig EV3E), demonstrating that VCP recruitment is critical for UBXD8 to restrain apoptosis. In another cell line MCF‐7, UBXD8 knockout also sensitized cells to drug‐induced cell death (Fig 5F), suggesting the role of UBXD8 to restrain apoptosis is not cell type specific.

Figure EV3. UBXD8 knockout sensitizes cells to apoptotic insults. Related to Fig 5 .

-

ARepresentative images of WT and ΔBAX ΔBAK HeLa cells treated with ActD and Doxo. Scale bar, 100 μm.

-

B, CRepresentative FACS (B) and quantitative analysis (C) of apoptosis in the indicated HeLa cells treated with ActD or Doxo.

-

D, EQuantitative analysis of apoptosis in the indicated HeLa cells treated with Doxo.

Data information: Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats (C–E). Statistics: two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test (C–E); ***P < 0.001.

In another assay of long‐term colony formation, we challenged HeLa cells with Doxo for 2 h and ActD for 4 h and then withdrew the drugs and continuously cultured the drug‐treated cells for 21 days. ΔUBXD8 cells formed fewer surviving colonies than WT cells; UBXD8 re‐expression completely rescued colony formation in ΔUBXD8 cells (Fig 5G). Together, these results demonstrate that UBXD8 antagonizes apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs.

UBXD8 mediates the degradation of BH3‐only proteins Noxa, Bnip3, and Bik

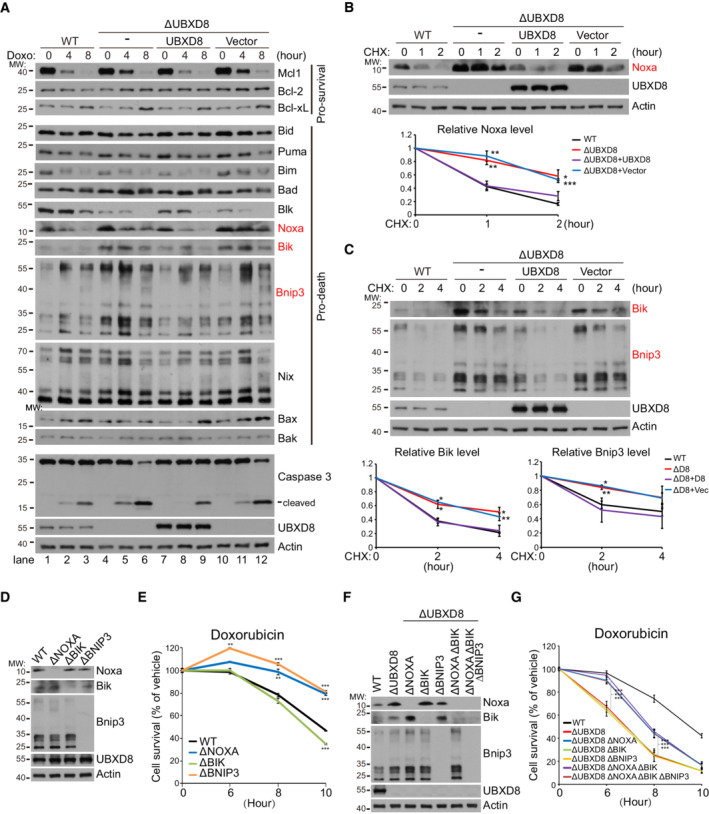

Because apoptosis is critically regulated by the balance of pro‐survival and pro‐death BH3‐domain containing proteins (Huang & Strasser, 2000; Giam et al, 2008), we examined the protein levels of BH3 family proteins in HeLa cells under Doxo treatment. Among all the examined proteins (pro‐survival proteins Mcl1, Bcl‐2, and Bcl‐xL; pro‐death proteins Bid, Puma, Bim, Bad, Blk, Noxa, Bik, Bnip3, Nix, Bak, and Bax), mitochondrial pro‐death BH3‐only proteins Noxa (Oda et al, 2000) and Bnip3 (Chen et al, 1997), and the ER pro‐death BH3‐only protein Bik (Boyd et al, 1995; Germain et al, 2005) accumulated in ΔUBXD8 cells before and after Doxo treatment (Fig 6A). Their aberrant accumulation was reduced by UBXD8 re‐expression in ΔUBXD8 cells (Fig 6A).

Figure 6. UBXD8 mediates the degradation of multiple BH3‐only proteins and restrains apoptosis via Noxa degradation.

-

AWestern blot analysis of BH3‐domain containing proteins in the indicated HeLa cells treated with Doxo (10 μM). Three proteins with enhanced level in ΔUBXD8 cells (Noxa, Bik, and Bnip3) are highlighted in red.

-

BWestern blot and quantitative analysis of Noxa degradation in the indicated HeLa cells.

-

CWestern blot and quantitative analysis of Bik and Bnip3 degradation in the indicated HeLa cells.

-

D–GWestern blot (D, F) and cell viability (E, G) analysis of the indicated HeLa cells. Cell viability was measured by Cell Titer‐Glo. Dox: 10 μM.

Data information: Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats (B, C, E, G). Statistics: two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test (B, C, E, G); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.001.

Source data are available online for this figure.

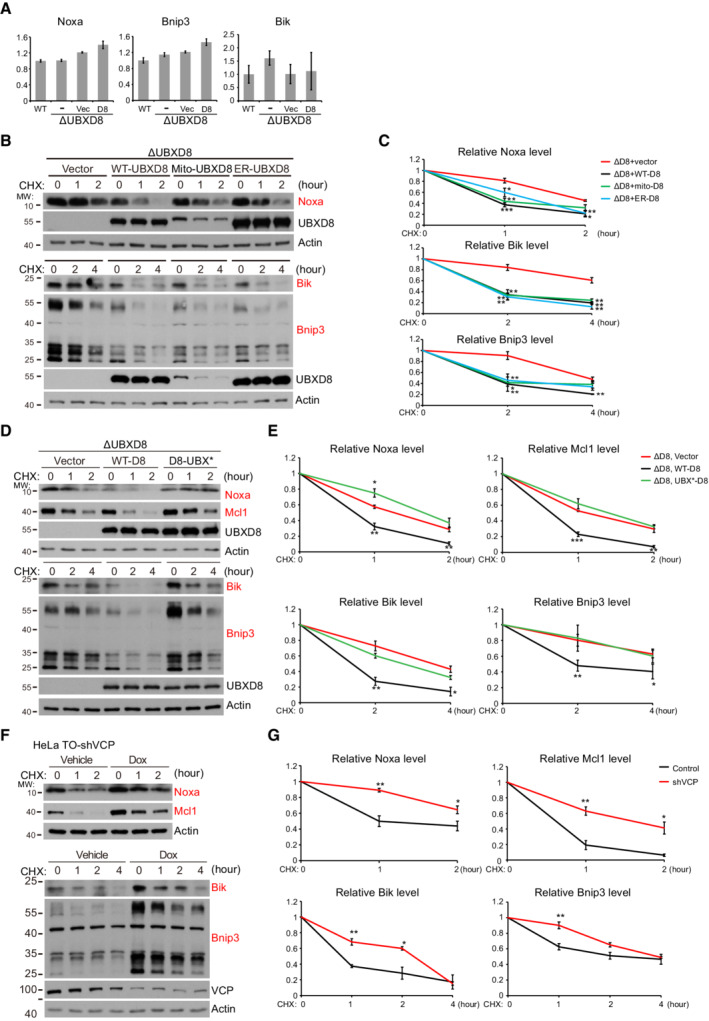

Noxa and Bik are ubiquitinated and degraded by the culin5 ubiquitin E3 ligase (Zhou et al, 2017; Chen et al, 2019); Bnip3 is also a substrate of the ubiquitin proteasome pathway (Poole et al, 2021). UBXD8 may be a common factor mediating their degradation. Indeed, the mRNA levels of Noxa, Bnip3, and Bik were not significantly altered by UBXD8 knockout (Fig EV4A). CHX chasing experiment confirmed that the degradation of these proteins was impaired in ΔUBXD8 cells and was restored by the re‐expression of WT, mito‐, and ER‐UBXD8 (Figs 6B and C, and EV4B and C), but not by the UBX* mutant (Fig EV4D and E). Furthermore, VCP knockdown significantly inhibited the degradation of Noxa, Bnip3, and Bik (Fig EV4F and G). Therefore, UBXD8 mediates the degradation of Noxa, Bik, and Bnip3 via recruiting VCP.

Figure EV4. The mRNA level and the degradation of Noxa, Bnip3, and Bik. Related to Fig 6 .

-

AQuantitative PCR analysis of the mRNA levels of Noxa, Bnip3, and Bik in the indicated HeLa cells. Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats.

-

B–GRepresentative western blot (B, D, F) and quantitative analysis (C, E, G) of the degradation of Mcl1, Noxa, Bnip3, and Bik in the indicated HeLa cells. In (F), VCP knockdown was induced by Doxycycline (1 μg/ml) treatment for 48 h. Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats (C, E, G). Statistics: two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test (C, E, G); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Source data are available online for this figure.

UBXD8 restrains apoptosis via Noxa degradation

To examine the role of Noxa, Bik, and Bnip3 in Doxo‐induced apoptosis, we generated ΔNOXA, ΔBIK, and ΔBNIP3 HeLa cells (Fig 6D). ΔNOXA and ΔBNIP3 cells showed resistance to Doxo‐induced apoptosis, and ΔBIK cells had similar sensitivity as WT cells (Fig 6E). We next knocked out these three BH3‐only proteins individually or in combination in ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells (Fig 6F). Knockout of Bnip3 or Bik did not affect the apoptosis sensitivity of ΔUBXD8 cells (Fig 6G). But Noxa knockout significantly increased the apoptosis resistance of ΔUBXD8 cells in response to Doxo treatment (Fig 6G). The ΔUBXD8 ΔNOXA ΔBIK ΔBNIP3 quadruple knockout cells had similar apoptosis sensitivity as ΔUBXD8 ΔNOXA cells (Fig 6G). These results clearly demonstrate that the accumulation of Noxa but not Bnip3 or Bik sensitizes ΔUBXD8 cells to apoptosis.

UBXD8 restrains mitophagy via Bnip3 degradation

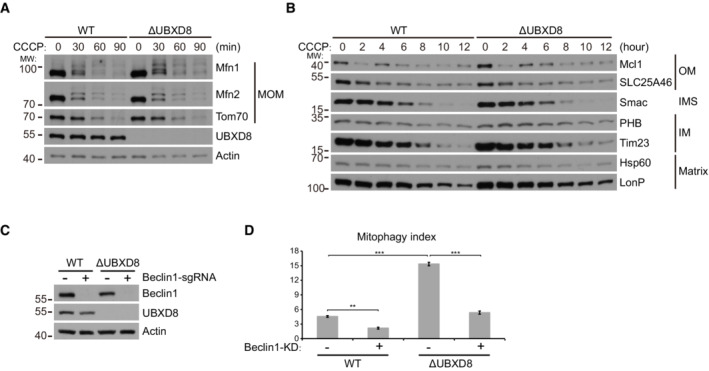

In the PINK1‐Parkin mitophagy pathway, VCP is recruited to mitochondria after Parkin‐mediated ubiquitination of MOM proteins and is required for mitofusin degradation and the subsequent mitophagy (Tanaka et al, 2010; Kim et al, 2013). We thus examined if UBXD8 plays a role in mitophagy. We stably expressed GFP‐Parkin in HeLa cells. CCCP treatment induced the rapid degradation of mitofusins and Tom70 and a relatively slower degradation of other proteins from all the mitochondrial compartments; this process was not impaired by UBXD8 knockout (Fig EV5A and B). These results demonstrate that UBXD8 is dispensable for Parkin‐mediated mitophagy.

Figure EV5. UBXD8 is dispensable for Parkin‐mediated mitochondrial degradation and Beclin1 knockdown blocks hyperactivated mitophagy in ΔUBXD8 cells. Related to Fig 7 .

-

A, BHeLa cells stably expressing GFP‐Parkin were treated with CCCP (15 μM) for the indicated time. The degradation of mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM), inter‐membrane space (IMS), inner membrane (IM), and matrix proteins were analyzed by western blot.

-

CWestern blot analysis of Beclin1 knockdown in the indicated HeLa cells.

-

DQuantitative analysis of mitophagy in the indicated HeLa cells. Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats. Statistics: one‐way ANOVA; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Source data are available online for this figure.

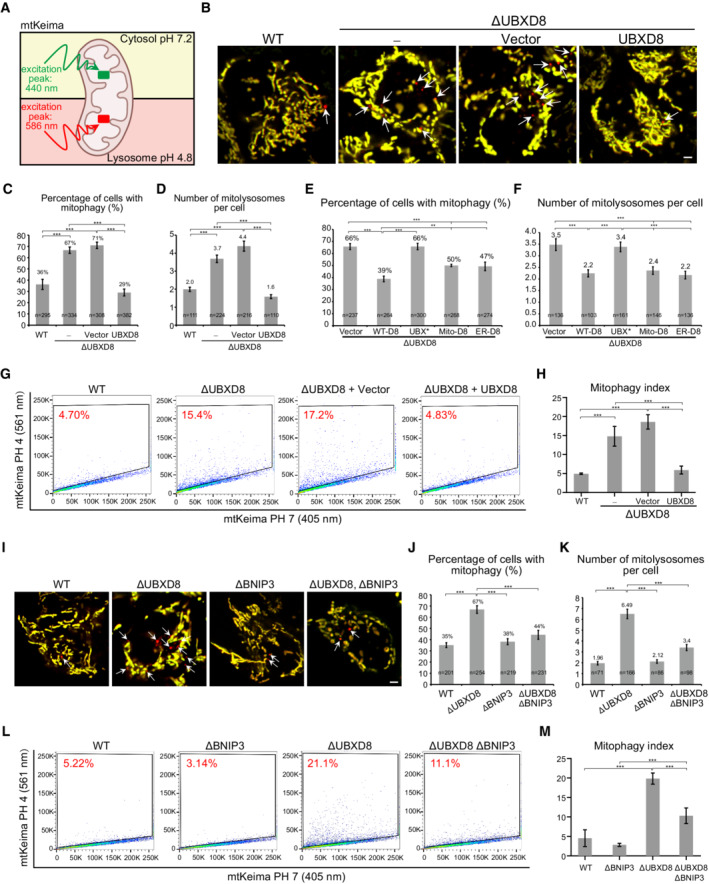

However, we were surprised to observe that ΔUBXD8 HeLa cells have enhanced mitophagy in the absence of Parkin overexpression. We used the mitoKeima reporter, a pH‐sensitive protein targeted to mitochondrial matrix, to monitor mitophagy (Katayama et al, 2011; Sun et al, 2015). MitoKeima has an emission spectrum that peaks at 620 nm and a bimodal excitation at 440 nm (at pH 7.2) and at 586 nm (at pH 4.0; Fig 7A). We labeled the emission from 405 nm excitation as green pseudo‐color and the emission from 561 nm excitation as red pseudo‐color (Fig 7B). Fluorescence imaging showed that ΔUBXD8 cells had more mitolysosomes (red dots pointed by white arrows) than WT cells (Fig 7B). Quantitative analysis of mitophagy events showed that ΔUBXD8 cells had a twofold increase in the percentage of cells with mitolysosomes and a twofold increase in the number of mitolysosomes per cell compared with WT cells; the enhanced mitophagy in ΔUBXD8 cells was rescued by WT, mito‐, and ER‐UBXD8, but not by the UBX* mutant (Fig 7C–F). We also performed FACS analysis of mitophagy. ΔUBXD8 cells exhibited a threefold increase in mitophagy in contrast to WT cells (from ∼5% to ∼15%); the elevated mitophagy in ΔUBXD8 cells was rescued by UBXD8 re‐expression (Fig 7G and H) and was abolished by knocking down Beclin1, a key autophagy gene (Fig EV5C and D).

Figure 7. UBXD8 restrains mitophagy via Bnip3 degradation.

-

ASchematic of the mitophagy reporter mtKeima. mtKeima is optimally excited at 440 nm at pH 7.2 and optimally excited at 586 nm at pH 4.8.

-

BRepresentative images of the mitophagy events in the indicated HeLa cells. mtKeima emission excited by 405 nm laser is shown as green; mtKeima emission excited by 561 nm laser is shown as red. Mitolysosomes are pointed by white arrows. Scale bar, 5 μm.

-

C–FQuantitative analysis of mitophagy events in the indicated HeLa cells. Only cells with mitophagy were selected to quantify mitolysosome numbers (D, F).

-

G, HRepresentative FACS (G) and quantitative analysis (H) of mitophagy index in the indicated HeLa cells.

-

I–KRepresentative images (I) and quantitative analysis of mitophagy events (J, K) in the indicated HeLa cells. White arrows point to mitolysosomes. Scale bar, 5 μm.

-

L, MRepresentative FACS (L) and quantitative analysis (M) of mitophagy index in the indicated HeLa cells.

Data information: Data are shown as mean ± SE from three biological repeats (C–F, H, J, K, M). Statistics: one‐way ANOVA (H, M); two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test (C–F, J, K); **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We noticed that the UBXD8 substrate Bnip3 is also a mitophagy receptor (Zhang et al, 2008; Onishi et al, 2021). Quantitative analysis of mitophagy events (Fig 7I–K) and FACS analysis (Fig 7L and M) consistently showed that the enhanced mitophagy in ΔUBXD8 was significantly reduced by Bnip3 knockout. Thus, Bnip3 accumulation hyperactivates mitophagy in ΔUBXD8 cells.

Discussion

UBXD8 is an extensively characterized VCP adaptor of ERAD. At the ER, UBXD8 forms the Derlin1/2‐UBXD8‐UBAC2‐GP78 and Derlin1/2‐UBXD8‐SEL1L‐Hrd1 complexes, in which GP78 and Hrd1 are ER ubiquitin E3 ligases (Alexandru et al, 2008; Mueller et al, 2008; Christianson et al, 2011). UBXD8 also localizes to lipid droplets to mediate local protein degradation (Zehmer et al, 2009; Suzuki et al, 2012; Olzmann et al, 2013). It was suggested that UBXD8 is targeted by Pex19 and Pex3 to the ER and mis‐localizes to mitochondria in Pex19‐null cells (Schrul & Kopito, 2016). In this study, we provide three layers of evidence (exogenously expressed UBXD8, endogenously tagged UBXD8, and endogenous UBXD8 recognized by antibody) to show that UBXD8 also localizes to mitochondria in normal cells (Fig 1). The mitochondrial localization of endogenous UBXD8 was confirmed by UBXD8 knockout (Fig 1E). The mitochondria and ER dual‐localization of UBXD8 is evolutionarily conserved as Ubx2, the yeast homolog of UBXD8, is also dually localized (Martensson et al, 2019). Like Ubx2, UBXD8 associates with the TOM complex but is dispensable for translocation‐associated degradation (Fig EV1), suggesting functional divergence across evolution.

Our characterizations demonstrate UBXD8 as an important MAD component. First, UBXD8 is a key factor recruiting VCP to mitochondria (Fig 2). Second, UBXD8 associates with mitochondrial ubiquitin E3 ligases MARCH5 and MUL1 and facilitates the degradation of their substrates (Figs 2 and 3). Third, in addition to MiD49 and Mcl1, we identify BH3‐only proteins Noxa, Bik, and Bnip3 as novel UBXD8 substrates (Fig 6). In HeLa cells, Noxa accumulation sensitizes ΔUBXD8 cells to apoptosis, mechanistically link MAD to apoptosis regulation (Fig 6). It is conceivable that UBXD8‐mediated degradation of Bik and Bnip3 may regulate apoptosis sensitivity in other cell types. More interestingly, UBXD8‐mediated MAD also regulates mitophagy via degrading the mitophagy receptor Bnip3 (Fig 7). Considering that UBXD8 is the major mitochondrial VCP adaptor, more mitochondrial substrates and mitochondrial functions may subject to regulation by UBXD8‐mediated MAD.

Our study also reveals the intimate crosstalk between MAD and ERAD. We show that ER‐localized VCP adaptor UBXD2 participates in MAD (Fig 3), and both mitochondria‐ and ER‐localized UBXD8 can mediate MAD and ERAD (Fig 4). The cross‐membrane degradation of substrates most likely occurs at the mitochondria‐ER contact site, where mitochondria and the ER juxtapose at a distance of ∼10–50 nm (Csordás et al, 2006; Wang et al, 2015; Giacomello & Pellegrini, 2016; Murley & Nunnari, 2016). Considering that a ubiquitin molecule has a diameter of ∼3.4 nm and the VCP hexamer has a diameter of ∼20 nm (Halawani et al, 2009), it is easy for poly‐ubiquitinated membrane proteins to be reached by the VCP complex on the opposite membrane at the mitochondria‐ER contact site. The close cooperation between MAD and ERAD may facilitate the degradation of a subset of mitochondrial/ER substrates that localize to or can diffuse into the contact site. However, because not all the ER and mitochondria are in contact, and because the ER is a highly compartmentalized organelle with subdomains different in protein composition and function (Lynes & Simmen, 2011), we speculate that MAD and ERAD cannot compensate each other for all the substrates, which necessitates mitochondria/ER‐resident adaptor‐VCP complexes.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and chemicals

Actin (Sigma‐Aldrich, A2066), AIF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC‐13116), Bad (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC‐8044), Bak (Cell Signaling Technology, 3814), Bax (Cell Signaling Technology, 5023), Beclin1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 3495), Bcl‐2 (Proteintech, 12789‐1‐AP), Bcl‐xL (Cell Signaling Technology, 2764), Bid (Cell Signaling Technology, 2002), Bik (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC‐365625), Bim (Cell Signaling Technology, 2933), Blk (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC‐65980), Bnip3 (Abcam, ab109362), Caspase‐3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9662), FLAG (Sigma‐Aldrich, F1804) Hsp60 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4870), LonP1 (Proteintech, 15440‐1‐AP), MARCH5 (Cell Signaling Technology, 19168), Mcl1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC‐819), Mfn1 (Proteintech, 13798‐1‐AP), Mfn2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9482), MiD49 (Proteintech, 16413‐1‐AP), Nix (Cell Signaling Technology, 12396), Noxa (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC‐56169), P4D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC‐8017), PARP (Cell Signaling Technology, 9542), Prohibitin (Proteintech, 12295‐1‐AP), Puma (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC‐374223), RNF185 (Abcam, ab181999), Smac (Cell Signaling Technology, 2954), Tim23 (Proteintech, 11123‐1‐AP), Tom22 (Proteintech, 11278‐1‐AP), Tom40 (Proteintech, 18409‐1‐AP), Tom70 (Proteintech, 14528‐1‐AP), UBXD2 (Proteintech, 21052‐1‐AP), UBXD8 (Cell Signaling Technology, 34945; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC‐374098), VCP (Proteintech, 10736‐1‐AP), Donkey anti‐rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 711‐035‐152), Goat anti‐mouse IgG (Sigma‐Aldrich, A5278), HA‐peroxidase (Sigma‐Aldrich, H6533).

Chemicals

Annexin V‐FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit (Abmaking, ABM0001K), actinomycin D (Abcam, ab141058), blasticidin (InvivoGen, ant‐bl), CCCP (Sigma‐Aldrich, C2759), chloramphenicol (Selleck, S1677), cycloheximide (VWR life science, 94271), digitonin (Sigma‐Aldrich, D5628), doxorubicin (Sigma‐Aldrich, D1515), doxycyclin (Frontier Scientific, D10056), ethidium bromide (Sigma‐Aldrich, E1510), G418 (Amresco, e859‐5), MG132 (CSNpharm, CSN11436), oligomycin (Abcam, ab141829), polybrene (Sigma‐Aldrich, H9268), Polyethylenimine (PEI; Polysciences, 23966‐1), puromycin (InvivoGen, ant‐pr‐1).

cDNAs and plasmids

cDNA and plasmids used and generated in this work are listed in Appendix Table S1.

Cell culture and transfection

U2OS, HeLa, HEK293T, and MCF7 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. All cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2.

For transfection, the PEI‐DNA mixture was made by mixing plasmid with PEI (1 mg/ml dissolved in distilled deionized water) at the ratio of 1 μg plasmid: 5 μl PEI and incubated 15 min at room temperature. Cells were transfected by the PEI‐DNA mixture for 6 h. The medium was then replaced and the cells were incubated at 37°C cell culture incubator.

Lentivirus production and generation of stable cell lines

HEK293T cells cultured in a well of 6‐well plate with 70% confluency were co‐transfected with gene‐expressing plasmids (1 μg) and lentiviral packaging vectors psPAX2 (0.6 μg) and pMD2.G (0.4 μg). Forty‐eight hours later, lentivirus was collected and filtered through a 0.45‐μm filter. For generating stable cell lines, 3 × 105 cells were seeded in a well of 6‐well plate and cultured for 24 h. Cells were infected with lentivirus in the presence of 10 μg/ml polybrene for 48 h. Infected cells were selected by 2 μg/ml puromycin (for FUIPW vector), 5 mg/ml G418 (for pLVX vector), and 50 μg/ml Blasticidin (for pLENTI‐TO vector) supplemented in the culture medium for 4 days. Gene expression was validated by immunoblotting.

Generation of knockout cell lines

Guide RNAs (gRNA) for target genes were cloned into PX458 (plasmid #48138, Addgene). Fifty percent confluent HeLa or MCF7 cells cultured in a well of 6‐cm dish were transfected with 2 μg PX458 plasmid. Two days later, the GFP‐positive cells were sorted into 96‐well plate by BD FACSAria III (BD Biosciences) and grown for 2 weeks. Single clones were trypsinized and expanded. UBXD8, UBXD2, NOXA, BIK, and BNIP3 knockout clones were identified by immunoblotting. MARCH5 knockout clones were identified by sequencing. The oligonucleotides of gRNAs and primers used to verify knockout clones are listed in Appendix Table S2.

Generation of FLAG knockin cell line

To generate the UBXD8 N‐terminal 3 × FLAG knockin U2OS cell line, gRNA (5′–3′ GCGCCGGCGGCCGTTCAGAC) targeting the 5' UTR of UBXD8 was cloned into PX458. The donor sequence containing the FLAG sequence flanked by ∼900‐bp homology arms complementary to the knockin site with PAM mutation was inserted into pBM16A T‐vector, (Biomad, CL071). U2OS cultured in 10‐cm dish with 70% confluency was transfected with 2 μg PX458 and 6 μg donor plasmid. Two days later, 2000 GFP‐positive cells were sorted by BD FACSAria III and cultured in 15‐cm dish for 3 weeks. Single clones were trypsinized and expanded. FLAG knockin clones were selected by immunoblotting and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The primers used to check correct insertion are listed in Appendix Table S2.

Isolation of mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum fractions

Mitochondria isolation

Cells cultured in four 15‐cm dishes (100% confluency) were washed once with PBS and scraped. Cells were centrifuged at 600 g for 5 min to pellet cells. Cell pellets were resuspended with 30 ml PBS and centrifuged again. Cell pellets were resuspended in 15 ml homogenization buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 0.5% (w/v) BSA) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 4693159001) and 1 mM PMSF and incubated on ice for 20 min. Cells were broken by a French press (EmulsiFlex‐C3, AVESTIN Inc.) at a pressure in the range of 1,000 ∼ 1,500 psi. Cell homogenates were centrifuged at 1,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. This step was repeated four times to thoroughly discard cell debris and the nuclear fraction. Supernatants were centrifuged at 19,800 g for 15 min at 4°C to pellet crude mitochondrial fraction. The crude mitochondrial pellets have a brown pellet enriched with mitochondria at the bottom and a white pellet with ER contaminants at the periphery. They were washed thoroughly to decrease ER contamination. In detail, crude mitochondrial pellets were rinsed with 5 ml homogenization buffer containing 1 mM PMSF. The peripheral white pellet was removed with a pipette. The brown mitochondrial pellets were resuspended with 5 ml homogenization buffer containing 1 mM PMSF and then centrifuged at 19,800 g for 10 min at 4°C. Mitochondrial pellets were rinsed with 5 ml homogenization buffer supplemented with 1 mM PMSF to remove the white pellet again. Enriched mitochondrial pellets were resuspended with 1 ml homogenization buffer containing 1 mM PMSF, split into two aliquots, centrifuged at 19,800 g for 10 min at 4°C. The mitochondrial pellets were snap‐frozen by liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

ER isolation

ER was isolated with the ER isolation kit (Sigma‐Aldrich, ER0100) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, cells cultured in eight 15‐cm dishes (90% confluency) were washed once with PBS and scraped. Cells were centrifuged at 600 g for 5 min to collect cells. Cell pellets were washed with 30 ml PBS and centrifuged again. Cells were resuspended in 9 ml 1× hypotonic extraction buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail for 20 min on ice. Cells were centrifuged at 600 g for 5 min. Cell pellets were resuspended with 6 ml 1× isotonic extraction buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail. Cells were broken with 10 strokes of Dounce homogenizer with a speed of 200 rpm. Cell homogenates were centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to discard cell debris and the nuclear fraction. Supernatants were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C to discard mitochondrial fraction. The floating lipid layer was removed and the supernatants were transferred to the Beckman ultracentrifuge tube, centrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 min at 4°C. ER pellets were resuspended by 1 ml PBS and centrifuged at 18,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The ER pellets were snap‐frozen by liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Immuprecipitation

To examine the interaction between UBXD8 and HA‐tagged ubiquitin E3 ligases, cells cultured in one 10‐cm dish (90–100% confluency) were collected and lysed by 1 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X‐100, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% Glycerol, 10 mM NaF) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 4693159001) for 30 min on ice. Cell extracts were centrifuged at 18,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. Supernatants were incubated with 20 μl anti‐HA agarose beads (Sigma‐Aldrich, A2095) for 8 h at 4°C. The beads were washed five times with the lysis buffer and eluted with 60 μl elute buffer (lysis buffer supplemented with 2 mg/ml HA peptide (ChinaPeptides Co. Ltd.), protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM DTT) overnight at 4°C. The elute product was boiled at 98°C for 10 min for subsequent immunoblotting analysis.

To examine the interaction between UBXD8 and endogenous MARCH5 and RNF185, FLAG‐UBXD8 knockin 293T cells cultured in one 10‐cm dish (90–100% confluency) were collected and lysed by 1 ml buffer A (50 mM HEPES‐KOH (pH 7.5), 50 mM Mg(OAc)2, 70 mM KOAc, 0.2% Triton X‐100, 0.2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 4693159001) for 30 min on ice. Cell extracts were centrifuged at 18,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to remove the pellet. Supernatants were incubated with 20 μl FLAG agarose beads (Sigma‐Aldrich, A2220) for 6 h at 4°C. The beads were washed five times with buffer A and eluted with 60 μl elute buffer (buffer A supplemented with 2 mg/ml FLAG peptide (ChinaPeptides Co. Ltd.), protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM DTT) overnight at 4°C. The eluted product was boiled at 98°C for 10 min for subsequent immunoblotting analysis.

To examine the interaction between FLAG‐UBXD8 and the TOM complex, mitochondrial fraction was purified as described above. Mitochondria pellet was solubilized with 1 ml 1% digitonin buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 1% (w/v) digitonin, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10% Glycerol) supplemented with 1 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 4693159001) for 1 h. The mitochondrial lysates were centrifuged at 18,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to discard the pellets. Supernatants were incubated with 15 μl FLAG agarose beads (Sigma‐Aldrich, A2220) for 6 h at 4°C. The beads were washed five times with 0.1% digitonin buffer and eluted with with 60 μl elute buffer (1% digitonin buffer supplemented with 2 mg/ml FLAG peptide (ChinaPeptides Co. Ltd.), protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM DTT) overnight at 4°C. The elute product was boiled at 98°C for 10 min for subsequent immunoblotting analysis.

Blue native PAGE

Mitochondrial fractions from cells cultured in three 15‐cm dishes were purified as described above. The mitochondrial pellets were washed two times by 1 ml homogenization buffer supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 4693159001), split into three to four aliquots, and snap‐frozen by liquid nitrogen. Mitochondrial proteins were prepared with NativePAGE™ Sample Prep Kit (Invitrogen, BN2008) according to manufacturer's instructions. In brief, one aliquot of mitochondrial pellet was thawed and solubilized by 80 μl 1 × sample buffer containing 1% digitonin on ice for 20 min. The supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 18,000 g for 10 min, and the protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay kit (Sigma, B6916). Ten microgram mitochondrial proteins were mixed with 1 × NativePAGE 5% G250 sample addictive buffer and loaded to 4–12% NuPAGE gel (Invitrogen, NP0336BOX). Electrophoresis was performed at 4°C by running with dark blue buffer (Invitrogen, BN2002) at 150 V for 40 min and then with light blue buffer at 250 V for 60 min. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane at 250 V for 1.5 h on ice and fixed on it by incubating the PVDF membrane in 8% acetic acid for 15 min. Unstained native markers were labeled by de‐coloring the PVDF membrane with methanol before washed membranes with deionized water. Then the membranes were subjected to immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting

Cells were collected and lysed with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X‐100, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 0.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 4693159001) and incubated on ice for 30 min. Cell lysates were then centrifuged at 18,000 g for 10 min to remove cell debris. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay kit (Sigma, B6916). Proteins were diluted with 4 × sample buffer (240 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 28% glycerol, 8% 2‐mercaptoethanol, 8% SDS, 0.08% Bromophenol Blue) and boiled at 98°C for 15 min. Ten to twenty‐five microgram proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE at 150 V for 70 min and then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare) at 400 mA for 1.5 h. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies in 5% non‐fat milk dissolved in PBST overnight. After washing with PBST 3 × 5 min, membranes were incubated with HRP‐conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Then membranes were washed three times and immunodetection was performed by Western Lightning Plus‐ECL (PerkinElmer, NEL120001EA).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

5 × 104 U2OS cells were seeded on glass coverslips and cultured for 1 day. To examine the localization of exogenously expressed proteins, 0.5 μg plasmids expressing interested proteins were transfected to cells and expressed for 24 h. After washing once with PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS for 3 × 5 min, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X‐100 in PBS for 30 min. Non‐specific binding was blocked with 10% BSA in PBS for 30 min. Cells were then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in PBS containing 10% BSA overnight at 4°C. The coverslips were washed with PBS for 3 × 5 min, then incubated with Alexa‐Fluor‐conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS for 3 × 5 min, coverslips were mounted onto slides.

To examine the localization of endogenous 3 × FLAG‐UBXD8 with the knockin cell line, an additional process was performed before fixing by treating cells with −20°C pre‐chilled methanol for 30 min on ice to decrease the non‐specific binding in cytosol. Fluorescent images were captured by an inverted fluorescence microscope Nikon A1 with a 60× oil objective (CFI Plan Apochromat Lambda; NA1.42; Nikon).

RNA isolation and qRT‐PCR

RNA was isolated following the TRIzol reagent user guide. Cells cultured in a 35‐mm dish (100% confluency) were lysed in 500 μl TRIzol reagent and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. One hundred microliter chloroform was added and fully mixed. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C and 200 μl aqueous phase containing RNA was transferred to a new tube. Then 200 μl isopropanol was added to the aqueous phase and mixed well to precipitate RNA. The RNA pellet was collected through centrifuging at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C and washed two times with 75% ethanol. The RNA pellet was air‐dried for 10 min and resuspended in 100 μl nuclease‐free H2O. Complementary DNA was synthesized with 1 μg RNA by 5 × All‐In‐One RT MasterMix (abm). qRT‐PCR reactions were prepared with TB Green Premix Ex Taq (Takara) and 25 ng cDNA template. qRT‐PCR was assayed by CFX96 Touch Real‐Time PCR Detection System (Bio‐Rad) with three biological replicates. ACTINB was selected as the reference gene for normalization. Primers used for qPCR are listed in Appendix Table S2.

Cell survival analysis

Cells were seeded in 96‐well plate (1.5 × 104 per well) and cultured for 1 day. Cells were treated with actinomycin D (1 μM) or doxorubinxin (10 μM) for 6, 8, and 10 h respectively. Cell survival was indicated by cellular ATP level measured with the Cell Titer‐Glo Luminescent assay kit (Promega, G7570). Briefly, cells were lysed by adding 30 μl CellTiter‐Glo reagent into the media and mixed on an orbital shaker for 5 min at room temperature. Luminescence signals were stabilized at room temperature for 10 min and recorded by the Enspire™ Multilabel Reader.

Annexin V‐FITC/PI staining

Annexin V‐FITC/PI staining was performed with Annexin V‐FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit (Abmaking, ABM0001K) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded in 6‐well plate (3.5 × 105 per well) and cultured for 1 day. Cells were treated with actinomycin D (1 μM) or doxorubicin (10 μM) for 0, 6, and 8 h respectively. Both culture medium and trypsin digested cells are collected in a 15 ml BD tube and then centrifuged at 180 g for 5 min to harvest cells. Cells were washed twice with 5 ml pre‐cold PBS and resuspended with 1× binding buffer to reach a cell density of 1 × 106/ml. Five microliter Annexin V‐FITC was added to 100 μl cell suspension and incubated in the dark for 10 min at room temperature. Five microliter PI was added to the cell suspension and incubated in the dark for 5 min at room temperature. The cell suspension was diluted with 400 μl PBS and filtered by a 40 μm filter. The fluorescence of 1 × 104 cells was analyzed by BD FACSAria III and the results were processed with FlowJo V10 software.

Mitophagy assay

Stable cell line expressing mtKeima controlled by the tetracycline‐inducible promoter (TO‐mtKeima) were treated with doxycycline (1 μg/ml) for 48 h to induce mitoKeima expression and then cultured for another 24 h in doxycycline‐free media. For FACS analysis, cells were trypsinized and filtered by a 40 μm filter. The fluorescence of 1 × 104 cells was analyzed by BD FACSAria III and the results were processed with FlowJo V10 software. For imaging analysis, cells cultured in a 35‐mm glass‐bottom dish were imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope Nikon A1 with a 60× oil objective. Pictures were processed with ImageJ software.

Quantification and statistical analysis

For Fig 2E and CHX chasing experiments, protein bands were quantified using ImageJ software. Data were presented as mean ± SE from three replicates. Statistical significance was analyzed by the Student's two‐tailed, unpaired t‐test in Excel or one‐way ANOVA using Tukey's test in GraphPad Prism software as indicated in the figure legends. P‐values are denoted in figures as: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Author contributions

Hui Jiang: Conceptualization; supervision; funding acquisition; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Jing Zheng: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Yu Cao: Investigation; methodology. Jun Yang: Investigation.

In addition to the CRediT author contributions listed above, the contributions in detail are:

HJ and JZ conceived the study; JZ, YC, and JY performed experiments; JZ, YC, and HJ analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the editing of the manuscript.

Disclosure and competing interests statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Source Data for Expanded View

PDF+

Source Data for Figure 6

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31871346) and by institutional grants from the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, Beijing Municipal Commission of Science and Technology, and Tsinghua University.

EMBO reports (2022) 23: e54859

Data availability

No primary data sets have been generated and deposited.

References

- Alexandru G, Graumann J, Smith GT, Kolawa NJ, Fang R, Deshaies RJ (2008) UBXD7 binds multiple ubiquitin ligases and implicates p97 in HIF1alpha turnover. Cell 134: 804–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolome F, Wu HC, Burchell VS, Preza E, Wray S, Mahoney CJ, Fox NC, Calvo A, Canosa A, Moglia C et al (2013) Pathogenic VCP mutations induce mitochondrial uncoupling and reduced ATP levels. Neuron 78: 57–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JM, Gallo GJ, Elangovan B, Houghton AB, Malstrom S, Avery BJ, Ebb RG, Subramanian T, Chittenden T, Lutz RJ et al (1995) Bik, a novel death‐inducing protein shares a distinct sequence motif with Bcl‐2 family proteins and interacts with viral and cellular survival‐promoting proteins. Oncogene 11: 1921–1928 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun RJ, Zischka H, Madeo F, Eisenberg T, Wissing S, Buttner S, Engelhardt SM, Buringer D, Ueffing M (2006) Crucial mitochondrial impairment upon CDC48 mutation in apoptotic yeast. J Biol Chem 281: 25757–25767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YC, Hung WT, Chang YC, Chang HC, Wu CL, Chiang AS, Jackson GR, Sang TK (2011) Pathogenic VCP/TER94 alleles are dominant actives and contribute to neurodegeneration by altering cellular ATP level in a drosophila IBMPFD model. PLoS Genet 7: e1001288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FY, Huang MY, Lin YM, Ho CH, Lin SY, Chen HY, Hung MC, Chen RH (2019) BIK ubiquitination by the E3 ligase Cul5‐ASB11 determines cell fate during cellular stress. J Cell Biol 218: 3002–3018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Ray R, Dubik D, Shi L, Cizeau J, Bleackley RC, Saxena S, Gietz RD, Greenberg AH (1997) The E1B 19K/Bcl‐2‐binding protein Nip3 is a dimeric mitochondrial protein that activates apoptosis. J Exp Med 186: 1975–1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Liu L, Cheng Q, Li Y, Wu H, Zhang W, Wang Y, Sehgal SA, Siraj S, Wang X et al (2017) Mitochondrial E3 ligase MARCH5 regulates FUNDC1 to fine‐tune hypoxic mitophagy. EMBO Rep 18: 495–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherok E, Xu S, Li S, Das S, Meltzer WA, Zalzman M, Wang C, Karbowski M (2017) Novel regulatory roles of Mff and Drp1 in E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH5‐dependent degradation of MiD49 and Mcl1 and control of mitochondrial dynamics. Mol Biol Cell 28: 396–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson JC, Olzmann JA, Shaler TA, Sowa ME, Bennett EJ, Richter CM, Tyler RE, Greenblatt EJ, Harper JW, Kopito RR (2011) Defining human ERAD networks through an integrative mapping strategy. Nat Cell Biol 14: 93–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordás G, Renken C, Várnai P, Walter L, Weaver D, Buttle KF, Balla T, Mannella CA, Hajnóczky G (2006) Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria. J Cell Biol 174: 915–921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custer SK, Neumann M, Lu H, Wright AC, Taylor JP (2010) Transgenic mice expressing mutant forms VCP/p97 recapitulate the full spectrum of IBMPFD including degeneration in muscle, brain and bone. Hum Mol Genet 19: 1741–1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreveny I, Kondo H, Uchiyama K, Shaw A, Zhang X, Freemont PS (2004) Structural basis of the interaction between the AAA ATPase p97/VCP and its adaptor protein p47. EMBO J 23: 1030–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Khouri E, Le Pavec G, Toledano MB, Delaunay‐Moisan A (2013) RNF185 is a novel E3 ligase of endoplasmic reticulum‐associated degradation (ERAD) that targets cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). J Biol Chem 288: 31177–31191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgass KD, Smith EA, LeGros MA, Larabell CA, Ryan MT (2015) Analysis of ER–mitochondria contacts using correlative fluorescence microscopy and soft X‐ray tomography of mammalian cells. J Cell Sci 128: 2795–2804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain M, Mathai JP, McBride HM, Shore GC (2005) Endoplasmic reticulum BIK initiates DRP1‐regulated remodelling of mitochondrial cristae during apoptosis. EMBO J 24: 1546–1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomello M, Pellegrini L (2016) The coming of age of the mitochondria–ER contact: a matter of thickness. Cell Death Differ 23: 1417–1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giam M, Huang DC, Bouillet P (2008) BH3‐only proteins and their roles in programmed cell death. Oncogene 27: S128–S136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halawani D, LeBlanc AC, Rouiller I, Michnick Stephen W, Servant Marc J, Latterich M (2009) Hereditary inclusion body myopathy‐linked p97/VCP mutations in the NH2 domain and the D1 ring modulate p97/VCP ATPase activity and D2 ring conformation. Mol Cell Biol 29: 4484–4494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DC, Strasser A (2000) BH3‐only proteins‐essential initiators of apoptotic cell death. Cell 103: 839–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inuzuka H, Shaik S, Onoyama I, Gao D, Tseng A, Maser RS, Zhai B, Wan L, Gutierrez A, Lau AW et al (2011) SCF(FBW7) regulates cellular apoptosis by targeting MCL1 for ubiquitylation and destruction. Nature 471: 104–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JO, Mandrioli J, Benatar M, Abramzon Y, Van Deerlin VM, Trojanowski JQ, Gibbs JR, Brunetti M, Gronka S, Wuu J et al (2010) Exome sequencing reveals VCP mutations as a cause of familial ALS. Neuron 68: 857–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbowski M, Neutzner A, Youle RJ (2007) The mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH5 is required for Drp1 dependent mitochondrial division. J Cell Biol 178: 71–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbowski M, Youle RJ (2011) Regulating mitochondrial outer membrane proteins by ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 23: 476–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama H, Kogure T, Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Miyawaki A (2011) A sensitive and quantitative technique for detecting autophagic events based on lysosomal delivery. Chem Biol 18: 1042–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NC, Tresse E, Kolaitis RM, Molliex A, Thomas RE, Alami NH, Wang B, Joshi A, Smith RB, Ritson GP et al (2013) VCP is essential for mitochondrial quality control by PINK1/parkin and this function is impaired by VCP mutations. Neuron 78: 65–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JN, Kim H, Yao H, Chen Y, Weng K, Ye J (2010) Identification of Ubxd8 protein as a sensor for unsaturated fatty acids and regulator of triglyceride synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 21424–21429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JN, Zhang X, Feramisco JD, Gong Y, Ye J (2008) Unsaturated fatty acids inhibit proteasomal degradation of Insig‐1 at a postubiquitination step. J Biol Chem 283: 33772–33783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Bengtson MH, Ulbrich A, Matsuda A, Reddy VA, Orth A, Chanda SK, Batalov S, Joazeiro CA (2008) Genome‐wide and functional annotation of human E3 ubiquitin ligases identifies MULAN, a mitochondrial E3 that regulates the organelle's dynamics and signaling. PLoS ONE 3: e1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Yin C, Doong H, Fang S, Peterhoff C, Nixon RA, Monteiro MJ (2006) Characterization of erasin (UBXD2): a new ER protein that promotes ER‐associated protein degradation. J Cell Sci 119: 4011–4024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludtmann MHR, Arber C, Bartolome F, de Vicente M, Preza E, Carro E, Houlden H, Gandhi S, Wray S, Abramov AY (2017) Mutations in valosin‐containing protein (VCP) decrease ADP/ATP translocation across the mitochondrial membrane and impair energy metabolism in human neurons. J Biol Chem 292: 8907–8917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynes EM, Simmen T (2011) Urban planning of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER): how diverse mechanisms segregate the many functions of the ER. Biochim Biophy Acta 1813: 1893–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen L, Kriegenburg F, Vala A, Best D, Prag S, Hofmann K, Seeger M, Adams IR, Hartmann‐Petersen R (2011) The tissue‐specific Rep8/UBXD6 tethers p97 to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane for degradation of misfolded proteins. PLoS ONE 6: e25061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martensson CU, Priesnitz C, Song J, Ellenrieder L, Doan KN, Boos F, Floerchinger A, Zufall N, Oeljeklaus S, Warscheid B et al (2019) Mitochondrial protein translocation‐associated degradation. Nature 569: 679–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller B, Klemm EJ, Spooner E, Claessen JH, Ploegh HL (2008) SEL1L nucleates a protein complex required for dislocation of misfolded glycoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 12325–12330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murley A, Nunnari J (2016) The emerging network of mitochondria‐organelle contacts. Mol Cell 61: 648–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuber O, Jarosch E, Volkwein C, Walter J, Sommer T (2005) Ubx2 links the Cdc48 complex to ER‐associated protein degradation. Nat Cell Biol 7: 993–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda E, Ohki R, Murasawa H, Nemoto J, Shibue T, Yamashita T, Tokino T, Taniguchi T, Tanaka N (2000) Noxa, a BH3‐only member of the Bcl‐2 family and candidate mediator of p53‐induced apoptosis. Science 288: 1053–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olzmann JA, Richter CM, Kopito RR (2013) Spatial regulation of UBXD8 and p97/VCP controls ATGL‐mediated lipid droplet turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 1345–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi M, Yamano K, Sato M, Matsuda N, Okamoto K (2021) Molecular mechanisms and physiological functions of mitophagy. EMBO J 40: e104705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MJ, Voeltz GK (2016) Structure and function of ER membrane contact sites with other organelles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17: 69–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole LP, Bock‐Hughes A, Berardi DE, Macleod KF (2021) ULK1 promotes mitophagy via phosphorylation and stabilization of BNIP3. Sci Rep 11: 20526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladi S, Boos F, Poglitsch M, Meyer H, Sommer F, Mühlhaus T, Schroda M, Schuldiner M, Madeo F, Herrmann JM (2020) The NADH dehydrogenase Nde1 executes cell death after integrating signals from metabolism and Proteostasis on the mitochondrial surface. Mol Cell 77: 189–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrul B, Kopito RR (2016) Peroxin‐dependent targeting of a lipid‐droplet‐destined membrane protein to ER subdomains. Nat Cell Biol 18: 740–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuberth C, Buchberger A (2005) Membrane‐bound Ubx2 recruits Cdc48 to ubiquitin ligases and their substrates to ensure efficient ER‐associated protein degradation. Nat Cell Biol 7: 999–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Herrmann JM, Becker T (2021) Quality control of the mitochondrial proteome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 22: 54–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N, Yun J, Liu J, Malide D, Liu C, Rovira II, Holmstrom KM, Fergusson MM, Yoo YH, Combs CA et al (2015) Measuring in vivo mitophagy. Mol Cell 60: 685–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Otsuka T, Ohsaki Y, Cheng J, Taniguchi T, Hashimoto H, Taniguchi H, Fujimoto T (2012) Derlin‐1 and UBXD8 are engaged in dislocation and degradation of lipidated ApoB‐100 at lipid droplets. Mol Biol Cell 23: 800–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A, Cleland MM, Xu S, Narendra DP, Suen D‐F, Karbowski M, Youle RJ (2010) Proteasome and p97 mediate mitophagy and degradation of mitofusins induced by parkin. J Cell Biol 191: 1367–1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Boom J, Meyer H (2018) VCP/p97‐mediated unfolding as a principle in protein homeostasis and signaling. Mol Cell 69: 182–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PTC, Garcin PO, Fu M, Masoudi M, St‐Pierre P, Panté N, Nabi IR (2015) Distinct mechanisms controlling rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum contacts with mitochondria. J Cell Sci 128: 2759–2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts GD, Wymer J, Kovach MJ, Mehta SG, Mumm S, Darvish D, Pestronk A, Whyte MP, Kimonis VE (2004) Inclusion body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia is caused by mutant valosin‐containing protein. Nat Genet 36: 377–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz IE, Kusam S, Lam C, Okamoto T, Sandoval W, Anderson DJ, Helgason E, Ernst JA, Eby M, Liu J et al (2011) Sensitivity to antitubulin chemotherapeutics is regulated by MCL1 and FBW7. Nature 471: 110–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Li L, Jiang H (2016) Doa1 targets ubiquitinated substrates for mitochondria‐associated degradation. J Cell Biol 213: 49–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Cherok E, Das S, Li S, Roelofs BA, Ge SX, Polster BM, Boyman L, Lederer WJ, Wang C et al (2016) Mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH5 controls mitochondrial fission and cell sensitivity to stress‐induced apoptosis through regulation of MiD49 protein. Mol Biol Cell 27: 349–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HZ, Nalbandian A, Hsu CI, Li S, Llewellyn KJ, Mozaffar T, Kimonis VE, Weiss JH (2012) Slow development of ALS‐like spinal cord pathology in mutant valosin‐containing protein gene knock‐in mice. Cell Death Dis 3: e374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun J, Puri R, Yang H, Lizzio MA, Wu C, Sheng Z‐H, Guo M (2014) MUL1 acts in parallel to the PINK1/parkin pathway in regulating mitofusin and compensates for loss of PINK1/parkin. Elife 3: e01958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehmer JK, Bartz R, Bisel B, Liu P, Seemann J, Anderson RG (2009) Targeting sequences of UBXD8 and AAM‐B reveal that the ER has a direct role in the emergence and regression of lipid droplets. J Cell Sci 122: 3694–3702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Bosch‐Marce M, Shimoda LA, Tan YS, Baek JH, Wesley JB, Gonzalez FJ, Semenza GL (2008) Mitochondrial autophagy is an HIF‐1‐dependent adaptive metabolic response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem 283: 10892–10903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zhang T, Mishra P, Hay BA, Chan D, Guo M (2017) Valosin‐containing protein (VCP/p97) inhibitors relieve Mitofusin‐dependent mitochondrial defects due to VCP disease mutants. Elife 6: e17834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Li L, Jiang H (2019) Molecular pathways of mitochondrial outer membrane protein degradation. Biochem Soc Trans 47: 1437–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Q, Gao W, Du F, Wang X (2005) Mule/ARF‐BP1, a BH3‐only E3 ubiquitin ligase, catalyzes the polyubiquitination of Mcl‐1 and regulates apoptosis. Cell 121: 1085–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Xu J, Li H, Xu M, Chen ZJ, Wei W, Pan Z, Sun Y (2017) Neddylation E2 UBE2F promotes the survival of lung cancer cells by activating CRL5 to degrade NOXA via the K11 linkage. Clin Cancer Res 23: 1104–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziviani E, Tao RN, Whitworth AJ (2010) Drosophila parkin requires PINK1 for mitochondrial translocation and ubiquitinates Mitofusin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 5018–5023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]