Abstract

Four GATA family DNA binding proteins mediate nitrogen catabolite repression-sensitive transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gln3p and Gat1p are transcriptional activators, while Dal80p and Deh1p repress Gln3p- and Gat1p-mediated transcription by competing with these activators for binding to DNA. Strong Dal80p binding to DNA is thought to result from C-terminal leucine zipper-mediated dimerization. Many Dal80p binding site-homologous sequences are relatively evenly distributed across the S. cerevisiae genome, raising the possibility that Dal80p might be able to “stain” DNA. We demonstrate that cells containing enhanced green fluorescent protein-Dal80p (EGFP-Dal80p) exhibit up to 16 fluorescent foci that colocalize with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole)-positive material and follow DNA movement through the cell cycle, suggesting that EGFP-Dal80p may indeed be useful for monitoring yeast chromosomes in live cells and in real time.

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae GATA family transcription factors are responsible for nitrogen catabolite repression (NCR)-sensitive gene expression (for reviews, see references 6, 18, and 24). Gln3p and Gat1p are transcriptional activators, while Dal80p and Deh1p (Gzf3p) are repressors of Gln3p- and Gat1p-mediated transcription. The functionality of Gln3p and Gat1p in response to nitrogen availability is controlled by their access to the nucleus. In cells provided with a poor nitrogen source (e.g., proline), Gln3p and Gat1p are predominantly nuclear, and NCR-sensitive gene expression is high (2–4, 8, 9, 17). In contrast, when excess nitrogen is present (e.g., with glutamine), these transcription factors are cytoplasmic, and NCR-sensitive gene expression is repressed (2–4, 8, 9, 17).

In addition to NCR, Gln3p- and Gat1p-mediated transcription is regulated by the repressors, Dal80p and Deh1p (7, 18, 24). Several lines of evidence suggest that Dal80p down-regulates transcription by competing with Gln3p and Gat1p for binding to their target GATA sequences upstream of NCR-sensitive genes (1, 10–12, 14). Although Dal80p and Gln3p both bind to GATAs (13), their binding sites differ significantly. Gln3p binds to single GATAs, while two GATAs oriented head to tail or tail to tail, but not head to head, 15 to 40 bp apart are required for Dal80p binding (10). The observed strength of Dal80p binding to DNA has been suggested to derive from the fact that it does so as a dimer, which forms through C-terminal leucine zipper motifs (23). In addition, Dal80p appears to possess unlimited access to the nucleus independent of nutritional conditions (M. Distler and T. G. Cooper, unpublished data).

A homology search, conducted as part of a genomic analysis of Dal80p-regulated genes (7), resulted in identification of an unusually large number of Dal80p binding site-homologous sequences relatively evenly distributed throughout the genome. This raised the possibility that enhanced green fluorescent protein-Dal80p (EGFP-Dal80p) might be used as a probe to monitor chromosome movement in yeast. Although DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining and fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis have been used to visualize chromosomes, both methods are ill-suited for use with live preparations. Therefore, we determined whether Dal80p possessed any potential in this regard. Our data suggest that EGFP-Dal80p may indeed be a useful probe with which to monitor yeast chromosomes in live cells and in real time.

Multiple fluorescent foci appear in cells containing GFP-Dal80p.

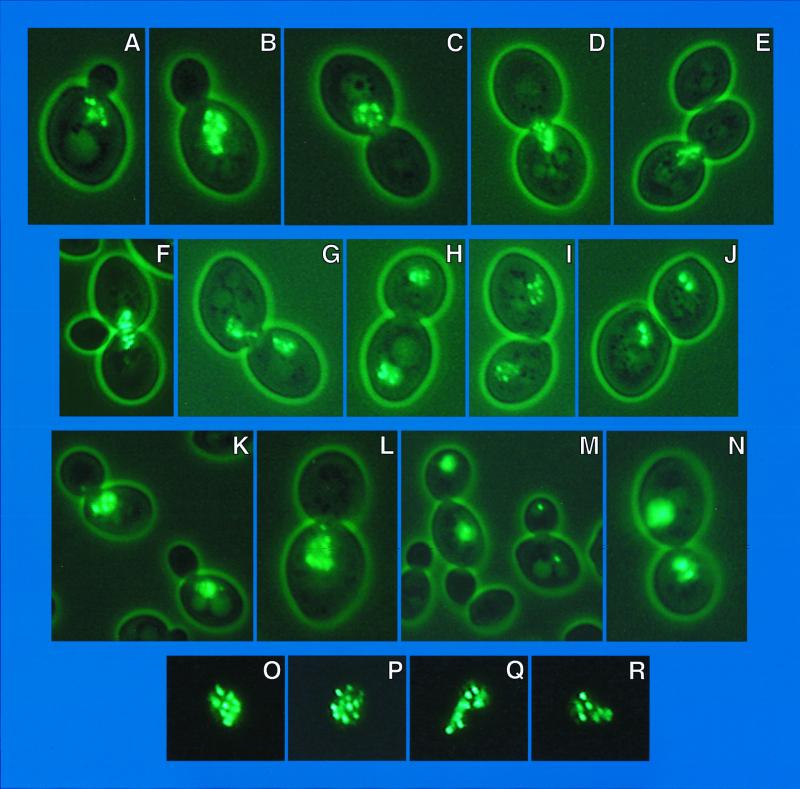

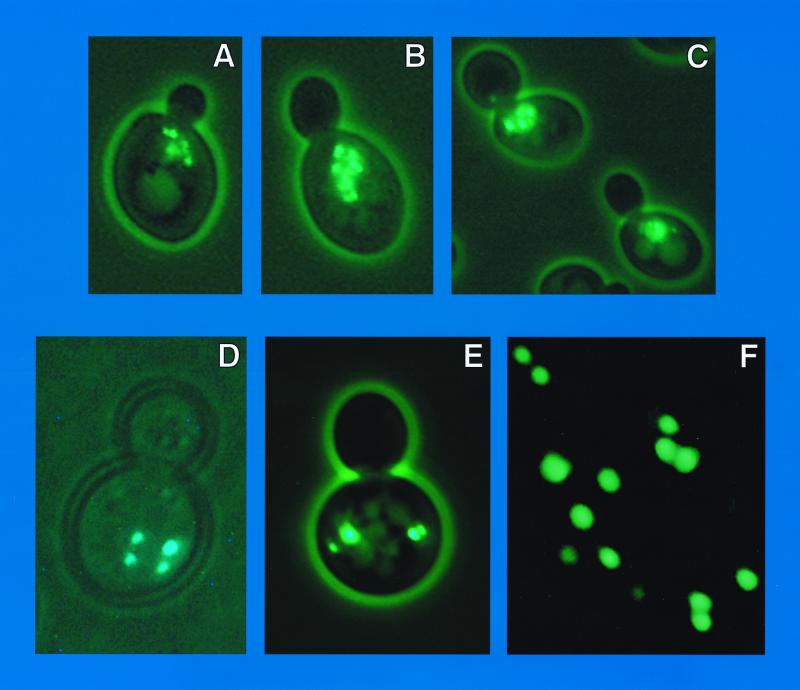

When wild-type S. cerevisiae is transformed with plasmid-borne GAL1,10-GFP-GLN3 or GAL1,10-GFP-GAT1, fluorescence is uniformly distributed in the nucleus (8, 9). In contrast, nuclear fluorescence is punctate when a GFP-DAL80 plasmid is used (Fig. 1). As the cell cycle progresses, these foci move within the cell and between mother and daughter cells as does DAPI-positive material. At the early bud stage, the foci cluster adjacent to the forming bud (Fig. 1A, B, K, and L). As the bud grows to the same size as the mother cell, fluorescent foci span the neck, often lined up like beads on a string (Fig. 1C to F). As cytokinesis occurs, fluorescent foci are situated in both mother and daughter cells (Fig. 1G to J, M, and N). Occasionally, the fluorescent foci form a circle or part of one (Fig. 1C and I).

FIG. 1.

GAL1,10-EGFP-DAL80 in wild-type GYC86 transformed with pNVS80. All strains, methods, and culture conditions were described earlier (8, 9, 19). Neither the nitrogen source nor overproduction of Ure2p affects the pattern or distribution of fluorescence (data not shown). The nitrogen sources were 0.1% proline (A to E and G to J), glutamine (K to N), or ammonia (F and O to R). pNVS80 was constructed by cloning the NdeI-HindIII fragment of pTSC416 into the NdeI and HindIII sites of pNVS2. GAL1,10-EGFP-DAL80 in pNVS80 was able to complement the GAT1 overproduction defect in a dal80::hisG mutant (R. Andhare and T. G. Cooper, data not shown). Higher-quality images of all color photographs are available upon request.

GFP-Dal80p-generated fluorescence colocalizes with DAPI-positive material.

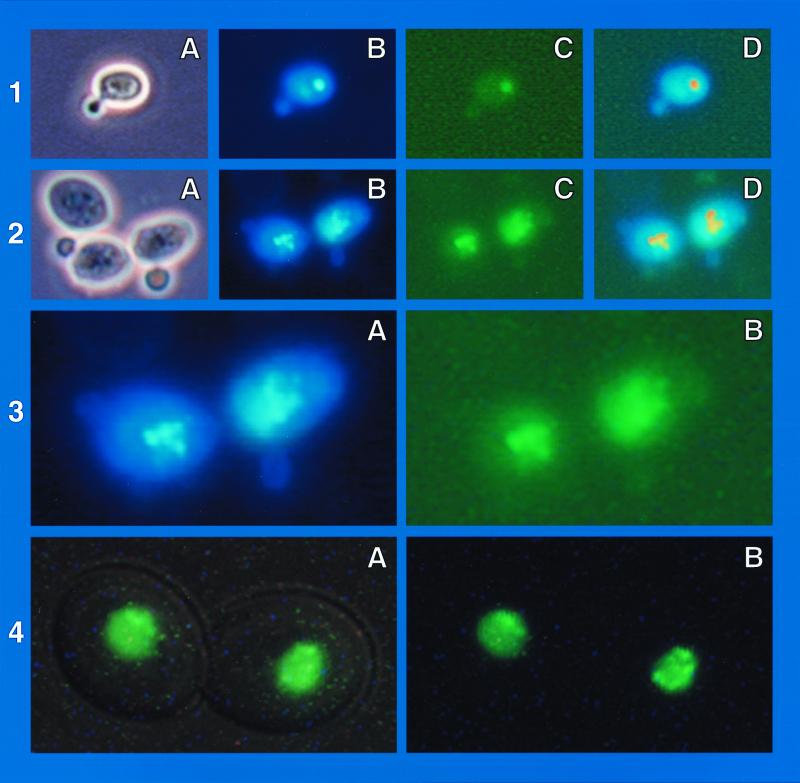

Since GFP-Dal80p-generated fluorescent foci move through the cell cycle in the same way as DAPI-stained material, we determined whether GFP-fluorescence and DAPI-positive material colocalize and found that they do (Fig. 2, rows 1 and 2). Further, occasionally DAPI-stained images exhibit defined foci as seen with GFP-Dal80p (Fig. 2, frames 2B and 2C). This is more clearly seen at higher magnification (Fig. 2, frames 3A and 3B). Note that this was observed only when unfixed cells were stained with DAPI.

FIG. 2.

(Rows 1 and 2) Colocalization of DAPI-positive material and GFP-Dal80p fluorescence in cells prepared as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Frames A to C were made using white light, DAPI, and GFP filter sets, respectively. Frames of DAPI-stained cells (B frames) were superimposed on frames of GFP-Dal80p-generated fluorescence (C frames) after the DAPI-positive material was pseudocolored red (D frames). In all cases colocalization was observed (indicated as yellow in the D frames). (Row 3) Enlargements of the B and C frames of row 2. (Row 4) GYC86 transformed with pNVS82, containing GAL1,10-EGFP-DAL82, prepared as described earlier (22). The slide in frame 4A was illuminated with a small amount of white as well as fluorescent light; in frame 4B only fluorescent light was used.

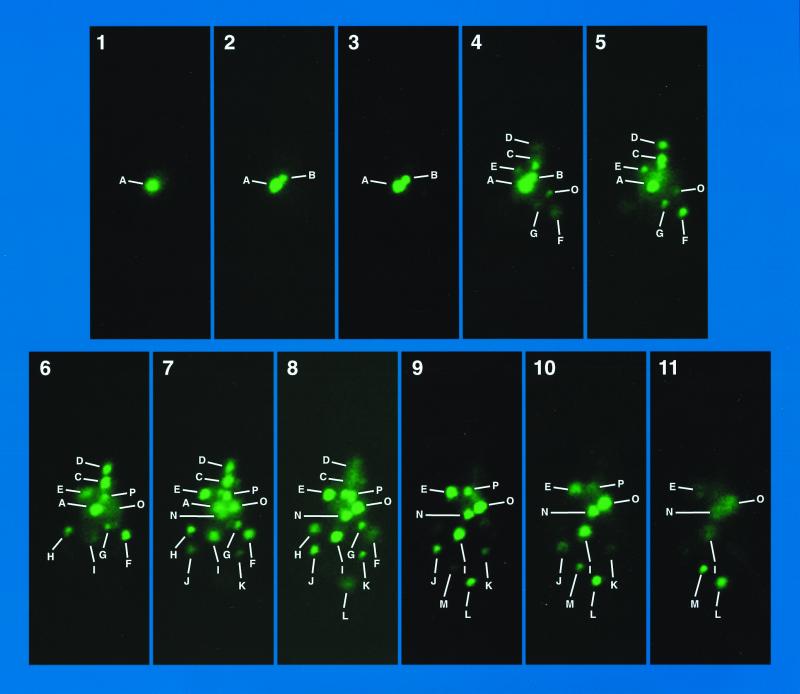

Confocal analysis of GFP-Dal80-generated fluorescent foci.

If the GFP-Dal80p fluorescent foci are associated with yeast chromosomes, one would expect to observe up to 16 of them. Therefore, we used confocal microscopy to unambiguously monitor the individual foci, thereby permitting us to determine their number (Fig. 3); foci are lettered to facilitate tracking them through the optical sections. We observed 16 distinct foci that differ in size and fluorescence intensity, and one of them, P, appears to possess a distinctive shape, which has been noticed in a number of confocal image sets. Computer reconstruction of the 11 confocal images from Fig. 3 is shown in Fig. 4. Although this result has been replicated multiple times, we cannot resolve 16 foci in every set of confocal images. We more often can unequivocally distinguish only 13 to 15 foci. We also performed deconvolution reconstructions of cell images. Here, 15 discrete foci can be distinguished, although one is quite faint (Fig. 5F).

FIG. 3.

Z sections generated by confocal microscopy (Zeiss Axiovert) of GYC86 transformed with GAL1,10-GFP-DAL80 pNVS80. Unique foci are lettered A to P.

FIG. 4.

Computer reconstruction of information derived from the Z sections depicted in Fig. 3 that are superimposed on a light micrograph of the cell analyzed. This reconstruction was performed using the Zeiss LSM510 reconstruction program.

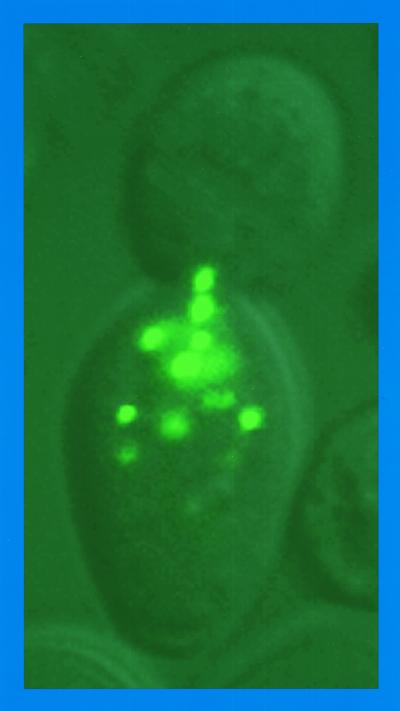

FIG. 5.

Expression of GAL1,10-EGFP-DAL80 pNVS80 in wild-type GYC86 (A to C) and a bim1Δ strain (Research Genetics BY20147 [MATa his3D1 leu2D0 met15D0 ura3D0 bim1::kan1/MATα his3D1 leu2D0 lys2DO ura3D bim1::kan1]) (D and E). Patterns of EGFP-Dal80p localization are the same in GYC86 and BY4743, the isogenic wild-type strain of BY20147. (F) Deconvolution reconstruction of a GYC86 cell transformed with GAL1,10-EGFP-DAL80 pNVS80. The image was prepared using Deltavision software.

GFP-Dal80p in a bim1Δ mutant.

The above data prompted us to compare the distributions of fluorescent foci in wild-type and bim1Δ cells. Bim1p is required to correctly position the mitotic spindle (19, 20). In about 20 to 25% of bim1Δ cells, the mitotic spindle misaligns such that its axis is perpendicular to the normal axis running from mother to daughter cell (19). As a result, DAPI-positive material moves to opposite sides of the mother cell rather than entering the daughter cell (see Fig. 3A in reference 19). In wild-type cells, GFP-Dal80p fluorescent foci collect near the neck between mother and daughter cells (Fig. 5A to C). In the bim1Δ mutant, at an equal or slightly later stage of the cell cycle (Fig. 5D and E), the fluorescent foci are situated quite removed from the neck, in a pattern identical to that observed with DAPI-stained bim1Δ cells (19).

GFP-Dal82p yields punctate fluorescent foci.

If GFP-Dal80p is visualizing yeast chromosomes, one might see a similar pattern of fluorescence with other molecules that bind tightly to DNA. Dal82p is the UISALL-binding protein required for inducer (OXLU)-mediated DAL gene expression (6, 15). Footprinting experiments demonstrate that Dal82p binds avidly to its target site, and the genome contains many UISALL-homologous sequences (25). Therefore, we reviewed micrographs made during a study of Dal82p localization (22). Although less clearly defined, a punctate pattern of fluorescence is evident (Fig. 2, row 4). The GFP-Dal82p punctate foci appear superimposed on a background of nuclear fluorescence similar to that observed with the DAPI-stained image mentioned above (compare rows 3 and 4 in Fig. 2).

Since Dal80p is a GATA binding transcription factor, it is not difficult to envision that the fluorescent foci represent Dal80p-DNA complexes, thereby arguing that GFP-Dal80p may be visualizing yeast chromosomes. However, two questions lead to skepticism about such an interpretation: (i) whether the genome contains sufficient GFP-Dal80p sites to illuminate individual chromosomes and (ii) why similar images are not observed with GFP-Gln3p, especially since Gln3p binds to a simpler structure (10, 13), i.e., a single GATA. Using previously documented characteristics of the Dal80p binding site, the genome contains 3,388 homologous sequences, randomly distributed across all chromosomes. The number of sites per chromosome ranged from 63 (chromosome I) to 439 (chromosome IV); 84% of them are within open reading frames. Since two Dal80p molecules bind per site, the overall number of Dal80p molecules that potentially bind may be as high as 6,776, assuming of course that all of the identified sites are able to bind Dal80p.

The second question is more difficult to answer, but two reasons may account for the difference. (i) Dal80p, probably as a result of dimerization (21), binds to DNA more avidly than Gln3p or Gat1p. The phenotypes of dal80 and gln3 deletions argue that Dal80p binds to promoter GATA elements in preference to Gln3p or Gat1p. If, on average, the GATA sequences are occupied relatively more often with Gln3p and Gat1p than with Dal80p, then dal80 mutants would not exhibit the strong phenotype reported (5, 6, 14, 18, 22, 24). Also correlating with this explanation is that the Dal82p footprint (25) is stronger than that obtained with Gln3p (21). (ii) It is conceivable that more than two Dal80p molecules bind to some sites. When DNA fragments containing “strong” Dal80p binding sites are used as probes in electrophoretic mobility shift assays, a second, much-higher-molecular-weight species is observed in addition to the normally expected band (10). If this slowly migrating species represents some level of further Dal80p polymerization, it would increase the fluorescent yield of each “good” Dal80p binding site.

Mammalian erythroid cell-specific GATA-1, GATA-2, and GATA-3 generate punctate staining in erythroblasts and megakaryocytes (16). The pattern of fluorescence, however, is different from what we describe here. Anti-GATA-1 antibody illuminates one or two foci per C88 cell and up to five foci per Buf707 cell. However, there is no evidence that they move during the cell cycle, and their number does not correlate with chromosome number (16).

In the past, it has not been possible to take full advantage of the large number of S. cerevisiae mutants with defects in normal chromosome movement and cell biology due to an inability to visualize them individually except in fixed preparations using fluorescent in situ hybridization or scanning or transmission electron microscopic procedures. DAPI staining visualizes DNA, but as little more than an amorphous spot. EGFP-Dal80p may offer an alternative methodology, providing a more detailed view of DNA movement in wild-type and mutant cells using real-time microscopy in living cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lorraine Albritton for bringing the Bim1p papers to our attention, Tim Higgins for preparing the artwork, and the University of Tennessee Yeast Group for suggestions to improve the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM-35642.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andre B, Talibi D, Boudekou S S, Hein C, Vissers S, Coornaert D. Two mutually exclusive regulatory systems inhibit UASGATA, a cluster of 5′GAT(A/T)A-3′ upstream from the UGA4 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:558–564. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.4.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck T, Hall M N. The TOR signaling pathway controls nuclear localization of nutrient-regulated transcription factors. Nature. 1999;402:689–692. doi: 10.1038/45287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertram P G, Choi J H, Carvalho J, Ai W, Zeng C, Chan T-F, Zheng X F S. Tripartite regulation of Gln3p by TOR, Ure2p, and phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35727–35733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardenas M E, Cutler N S, Lorenz M, Di Como C J, Heitman J. The TOR signaling cascade regulates gene expression in response to nutrients. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3271–3279. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisholm G, Cooper T G. Isolation and characterization of mutations that produce the allantoin-degrading enzymes constitutively in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1088–1095. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper T G. Allantion degradative system—an integrated transcriptional response to multiple signals. In: Marzluf G, Bambrl R, editors. Mycota III. Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag; 1996. pp. 139–169. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox K, Pinchak A B, Cooper T G. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis in S. cerevisiae by mini-array membrane hybridization. Yeast. 1999;15:703–713. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19990615)15:8<703::AID-YEA413>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox K H, Rai R, Distler M, Daugherty J R, Coffman J A, Cooper T G. GATA sequences function as TATA elements during nitrogen catabolite repression and when Gln3p is excluded from the nucleus by overproduction of Ure2p. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17611–1768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001648200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham T S, Andhare R, Cooper T G. Nitrogen catabolite repression of DAL80 expression depends on the relative levels of Gat1p and Ure2p production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14408–14414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham T S, Cooper T G. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae DAL80 repressor protein binds to multiple copies of GATAA-containing sequences. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5851–5861. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5851-5861.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham T S, Dorrington R A, Cooper T G. The UGA4 UASNTR site required for GLN3-dependent transcriptional activation also mediates DAL80-responsive regulation and DAL80 protein binding in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4718–4725. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4718-4725.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham T S, Rai R, Cooper T G. The level of DAL80 expression down-regulates GATA factor-mediated transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6584–6591. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.23.6584-6591.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham T S, Svetlov V V, Rai R, Smart W, Cooper T G. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gln3p binds to UASNTR elements and activates transcription of nitrogen catabolite repression-sensitive genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3470–3479. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3470-3479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daugherty J R, Rai R, ElBerry H M, Cooper T G. Regulatory circuit for responses of nitrogen catabolic gene expression to the GLN3 and DAL80 proteins and nitrogen catabolite repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:64–73. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.64-73.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorrington R A, Cooper T G. The DAL82 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae binds to the DAL upstream induction sequence (UIS) Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3777–3784. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.16.3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elefanty A G, Antoniou M, Custodio N, Carmo-Forseca M, Grosveld F G. GATA transcription factors associate with a novel class of nuclear bodies in erythroblasts and megakaryocytes. EMBO J. 2000;15:319–333. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardwick J S, Kuruvilla F G, Tong J K, Shamji A F, Schreiber S. Rapamycin-modulated transcription defines the subset of nutrient-sensitive signaling pathways directly controlled by the Tor proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14866–14870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman-Bang J. Nitrogen catabolite repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biotechnol. 1999;12:35–73. doi: 10.1385/MB:12:1:35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korinek W S, Copeland M J, Chaudhuri A, Chant J. Molecular linkage underlying microtubule orientation toward cortical sites in yeast. Science. 2000;287:2257–2259. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee L, Tirnauer J S, Li J, Schuyler S C, Liu J Y, Pellman D. Positioning of the mitotic spindle by a cortical-microtubule capture mechanism. Science. 2000;287:2260–2262. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rai R, Genbauffe F S, Sumrada R A, Cooper T G. Identification of sequences responsible for transcriptional activation of the allantoate permease in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:602–608. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott S, Dorrington R, Svetlov V, Beeser A E, Distler M, Cooper T G. Functional domain mapping and subcellular distribution of Dal82p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7198–7204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Svetlov V V, Cooper T G. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae GATA factors Dal80p and Deh1p can form homo- and heterodimeric complexes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5682–5688. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5682-5688.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ter Schure E G, van Riel N A, Verrips C T. The role of ammonia metabolism in nitrogen catabolite repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:67–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Vuuren H J J, Daugherty J R, Rai R, Cooper T G. Upstream induction sequence, the cis-acting element required for response to the allantoin pathway inducer and enhancement of operation of the nitrogen-regulated upstream activation sequence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7186–7195. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7186-7195.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]