Abstract

Rhodobacter sphaeroides cells containing an in-frame deletion within ccmA lack detectable soluble and membrane-bound c-type cytochromes and are unable to grow under conditions where these proteins are required. Only strains merodiploid for ccmABCDG were found after attempting to generate cells containing either a ccmG null mutation or a ccmA allele that should be polar on to expression of ccmBCDG, suggesting that CcmG has another important role in R. sphaeroides.

Because of their vital role in energy generation, there is considerable interest in determining how cytochromes bind their essential heme cofactor. Among cytochromes, c-type cytochromes are unique because heme is covalently attached to two cysteine thiolates of the polypeptide (22). From analyzing a series of genes (ccm) that are required for c-type cytochrome maturation (13, 31), it appears that a c-type cytochrome precursor protein and heme are translocated across the cytoplasmic membrane by the general export pathway and some combination of CcmABCD, respectively. Once exported, the cysteine thiolates at the c-type cytochrome heme attachment site are believed to form an intramolecular disulfide bond that must be reduced prior to covalent heme attachment (13, 31). CcmG is proposed to act in a pathway which facilitates the reduction of this disulfide bond because it contains a pair of redox active thiols (26) and has amino acid sequence similarity to disulfide oxidoreductases in the thioredoxin family (13, 31). The fact that some Ccm mutants have defects in assembly of heme a-containing proteins (19) or iron chelator production (9) underscores the importance of defining whether these proteins participate in other processes.

To assess the role of Rhodobacter sphaeroides Ccm proteins, we made mutations within the ccmABCDG locus. This facultative phototroph uses c-type cytochromes to generate energy when growing by aerobic respiration, by photosynthesis, or by anaerobic respiration (4, 16, 17). R. sphaeroides CcmA is involved in c-type cytochrome maturation since a nonpolar mutation in ccmA caused the loss of this class of electron carrier and an inability to grow under conditions when these proteins are required to generate energy. However, CcmG could have other roles in R. sphaeroides since strains containing a polar insertion in ccmG or a mutation in ccmA that should be polar on to expression of ccmBCDG were not isolated.

Growth and genetic procedures.

R. sphaeroides was grown at 30°C in Sistrom's medium A (3, 28) containing spectinomycin (25 μg/ml), kanamycin (25 μg/ml), or tetracycline (1 μg/ml) when necessary. Sistrom's medium A containing 7.5% sucrose was used to screen for sucrose sensitivity. Escherichia coli was grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium (24) with appropriate combinations of ampicillin (50 μg/ml), spectinomycin (25 μg/ml), kanamycin (25 μg/ml), tetracycline (10 μg/ml), or chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml). E. coli DH5α (Table 1) was used as a plasmid host while S17-1 was used for plasmid transfer (2). Mating pairs were plated aerobically on Sistrom's minimal medium A containing appropriate antibiotics to obtain exconjugants.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| R. sphaeroides | ||

| 2.4.1 | Wild type | Laboratory strain |

| CCMA1 | ccmA1::Ωspc | This work |

| CCMA2 | ccmA1::Ωspc-pSUP202 (Tcr; merodiploid) | This work |

| CCMA3 | ccmA2::pLO1 (Knr sucroses; merodiploid) | This work |

| CCMA4 | ΔccmA because it contains the ccmA2 allele | This work |

| CCMG2 | ccmG1::Ωspc-pSUP202 (Tcr; merodiploid) | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Plasmid maintenance | 1 |

| S17-1 | Donor for plasmid transfer to R. sphaeroides | 27 |

| Plasmids | ||

| p2-9 | R. capsulatus ccmABC | 12 |

| pCSP4 | Apr; ∼9.5-kb PstI ccmABCDG fragment cloned in pUC18 in opposite orientation as Plac | This work |

| pCSP20 | Apr; ∼3.5-kb BamHI ccm fragment cloned in pUC18 in opposite orientation as Plac | This work |

| pCSP20Ω1 | Apr; pCSP20 containing spc cloned into ccmA (source of ccmA1::spc allele) | This work |

| pCSP91 | Apr Spr; ∼5.5-kb BamHI fragment containing ccmA1::spc from pCSP20Ω1 cloned in pSup202 | This work |

| pHP45Ω | Source of spc gene | 7 |

| pLO1 | Knr; sacB; RP4 oriT; ColE1 ori | 14 |

| pRC10 | Knr; ∼1.5-kb fragment containing ccmA2 cloned into the Pmel site of pLO1 | This work |

| pRK4S | Tcr; ∼9.5-kb PstI fragment containing ccmABCDG cloned into pRK415 | This work |

| pRK415 | Tcr; broad-host-range plasmid | 11 |

| pSUP202 | Apr Tcr Cmr Mob+; pBR325 derivative | 27 |

| pTP1 | Apr; ∼11.5-kb PstI fragment containing ccmG1::spc in pUC18 | This work |

| pTP2 | Tcr; Spr; ccmG1::spc from pTP1 cloned into PstI site of pSUP202 | This work |

| pUI8298 | Tcr; ∼29-kb fragment with ccmABCDG on pLA2917 | This work |

| pUC18 | Apr; cloning vector | 32 |

Construction of probes and plasmids.

Plasmid p2-9 was used to generate Rhodobacter capsulatus ccmABC and ccmCD probes (12). R. sphaeroides ccmABCDG was cloned as an ∼9.5-kb PstI restriction endonuclease fragment from pUI8298 (5) into pUC18 (pCSP4) or pRK415 (pRK4S). The ∼3.5-kb and ∼1.1-kb ccm-containing BamHI restriction endonuclease fragments from pCSP4 were separetely cloned into pUC18 (pCSP20 and pCSP110-1, respectively). For DNA sequencing of the ccm locus (Fig. 1) (GenBank accession number U83136), either lac- or R. sphaeroides-specific primers were used.

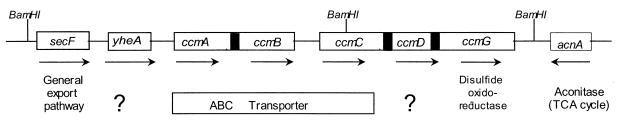

FIG. 1.

The R. sphaeroides ccmABCDG locus. Shown is the genetic organization of this locus (not drawn to scale; see below), the predicted direction of transcription (arrows), and the function of presumed gene products (bottom). Shaded boxes indicate where the predicted termination codon of one gene (ccmA, ccmC, and ccmD) overlaps the presumed initiation codon of the next gene (ccmB, ccmD, and ccmG, respectively).

A spectinomycin resistance gene (spc) (7) was inserted as a BamHI restriction endonuclease fragment into a unique BglII site of pCSP20 to create the ccmAI::spc allele (pCSP20Ω1). A BamHI restriction fragment containing ccmA1::spc from pCSP20Ω1 was purified, made blunt with T4 DNA polymerase I, and ligated into a blunt EcoRI site of the mobilizable suicide plasmid, pSUP202 (pCSP91). To generate ccmG1::spc, spc (7) was inserted as a SmaI restriction fragment into a unique BspEI site of pCSP4 (pTP1). A PstI restriction fragment from pPT1 containing ccmG1::spc was cloned into the PstI site of pSup202 (pTP2).

Mutant isolation.

Suicide plasmids were mated into R. sphaeroides (5) and Spr cells were screened for Tcs under aerobic conditions to identify strains where ccmA1::spc or ccmGI::spc was incorporated by an even number of crossover events (resulting in loss of Tcr).

Strains containing both a wild-type ccmABCDG locus and the ccmA1::spc or ccmG1::spc alleles (Spr, Tcr strains CCMA2 and CCMG2, respectively) were grown aerobically in antibiotic-free liquid medium prior to plating onto antibiotic-free agar in the presence of O2. Colonies were screened for Sp or Tc resistance to determine whether the ccmA1::spc or ccmG::spc alleles (Spr) or the suicide plasmid (Tcr) was present.

An in-frame deletion of ccmA codons 10 to 173 (ccmA2) was constructed by a two-step PCR process (17). Primers 5′-CGGCAGTCCGAGATCGATGTGGGCGAGGTTGGTGACGGT (CcmA-5′ tail) and 5′-CGGTCAACGAGACGCTGA3′ (CcmA-HincII 5′) were used to generate a PCR product containing ∼0.8 kb of upstream DNA and ccmA codons 1 to 9 fused in-frame to codons 174 to 179. To generate a PCR product that contains ccmA codons 4 to 9 fused in-frame to codons 174 to 210 plus ∼0.75 kb of downstream DNA, primers 5′-ACCGTCACCAACCTCGCCCACATCGATCTCGGACTGGCC (CcmA-3′ tailed) and 5′-GAATGGGGTCGCGACATC (CcmA-NruI 3′) were used. These two PCR products were purified, mixed with CcmA-HincII 5′ and CcmA-NruI 3′, and used in a second round of PCR to generate a product that contained ccmA2 flanked by ∼0.80 kb and ∼0.75 kb of upstream and downstream DNA. This product was purified, ligated into the PmeI site of the mobilizable suicide vector, pLO1 (pRC10), sequenced to verify the in-frame deletion of ccmA codons 10 to 173, and mated into R. sphaeroides. A resultant Knr, sucrose-sensitive exconjugant (CCMA3) was grown aerobically in the absence of antibiotics prior to plating ∼106 cells aerobically on medium supplemented with 7.5% sucrose. After 5 to 7 days of incubation, sucrose-resistant cells were screened for loss of Knr (from pLO1). DNA from sucrose-resistant, Kns cells was amplified and sequenced to verify that cells contained the ccmA2 allele and no other mutations within this gene.

Cytochrome analysis.

Soluble and membrane fractions were prepared from cultures grown under an atmosphere of 30% O2, 69% N2, 1% CO2. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Hercules, Calif.). Samples (∼400 μg of protein) were heated (70°C) for 10 min in the presence of 5% β-mercaptoethanol and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, c-type cytochromes were visualized by peroxidase activity (30).

The R. sphaeroides ccmABCDG locus.

Hybridization of R. sphaeroides DNA with R. capsulatus ccmABCDG-specific probes identified a related ∼9.5-kb PstI restriction fragment in genomic DNA and a wild-type gene library (pU18298). When R. sphaeroides DNA was analyzed by pulse-field electrophoresis (29) and probed with ccmABC, this locus mapped to coordinate ∼1500 on chromosome I (data not shown).

The DNA sequence of this region predicts the existence of seven complete open reading frames with codon usage typical of R. sphaeroides genes (Fig. 1). R. sphaeroides CcmA, CcmB, and CcmC each have significant amino acid similarity to other presumed family members (13, 31). Immediately downstream of ccmABC are two other genes (ccmDG) that could also encode Ccm homologues. The function of CcmD is unknown since the deduced polypeptide bears no significant relationship to proteins with known activity. CcmG has significant amino acid similarity to other family members, including a conserved sequence that is related to the active site of thioredoxin-type disulfide oxidoreductases. R. sphaeroides ccmABCDG could be cotranscribed since the initiation and termination codons for ccmAB, ccmCD, and ccmDG overlap (Fig. 1).

It appears that there are no other ccm genes in this region (Fig. 1). Upstream of yheA, which is not required for c-type cytochrome assembly in R. capsulatus (12), is a gene that encodes a predicted homologue of the general secretory protein, SecF (Fig. 1). Immediately downstream of ccmABCDG, and transcribed in the opposite direction (Fig. 1), is a gene that encodes a homologue of the tricarboxylic acid cycle enzyme aconitase.

Analysis of R. sphaeroides cells lacking CcmA.

To test if these presumed ccm gene products functioned in c-type cytochrome maturation, a strain containing an in-frame deletion within ccmA was generated (CCMA4). DNA sequence showed that this strain contains the ccmA2 allele and that the coding overlap between ccmA and ccmB was preserved, so this mutation should not have a negative effect on expression of any downstream genes. Cells lacking CcmA grew under aerobic but not photosynthetic or anaerobic respiratory conditions, the phenotypes predicted for R. sphaeroides cells that lack c-type cytochromes. Also, growth under these conditions was restored when this mutant contained ccmABCDG on a stable, low-copy-number plasmid.

To test if the ccmA2 allele caused the lack of c-type cytochromes, the accumulation of these proteins was measured in extracts from aerobically grown cells, a condition where R. sphaeroides contains several c-type cytochromes (4, 8, 17). The soluble and membrane proteins of wild-type cells that retain peroxidase activity under denaturing conditions (i.e., c-type cytochromes) were not detected in samples prepared from cells lacking CcmA (Fig. 2). In addition, reduced minus oxidized spectra of soluble and membrane extracts from aerobically grown cells which lack CcmA lacked the absorption feature that is present at ∼550 nm in wild-type cells and that is diagnostic of the c-type cytochromes (data not shown; 4, 8, 17).

FIG. 2.

Heme peroxidase staining of soluble and membrane samples from aerobically grown cells. For each sample, ∼400 ug of protein was heated at 70°C in the presence of 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Lanes 1 and 3 contain soluble and membrane samples from wild-type cells (2.4.1), respectively; lanes 2 and 4 contain soluble and membrane samples from cells lacking CcmA (CCMA4), respectively. Western blot analysis with antiserum against individual c-type cytochromes (date not shown) indicates that the soluble heme-staining protein in wild-type cells is mostly a combination of cytochrome c2 and cytochrome c554. Numbers at left are molecular weight markers (in thousands).

Could CcmG have additional roles in R. sphaeroides?

To test the role of other products of this locus, we attempted to place the ccmA1::spc allele (which should be polar on to expression of ccmBCDG) in the genome. Of 1,700 Spr cells screened for Tcs (Tcr encoded by the suicide plasmid) under aerobic conditions, only one strain (CcmA1) was identified that had lost the suicide plasmid. Control experiments with a cycA::kan allele on a similar suicide plasmid (7) found that ∼5% of the Knr cells (25/500) lost the suicide plasmid (i.e., became Tcs), so the frequency at which CcmA1 was obtained is below what is typically observed when generating null mutations by marker exchange in R. sphaeroides (2). When CcmA1 was analyzed further, it was found to contain a duplication of the ccmABCDG locus, grow via photosynthesis, and contain a normal complement of c-type cytochromes (data not shown). Thus, the only strain from which the suicide plasmid was lost contained a second intact copy of the ccmABCDG locus. We also attempted to place a ccmG1::spc allele in wild-type cells. In this case, when Spr cells were screened for Tcs, none were found among ∼3,100 independent Spr isolates.

R. sphaeroides CcmG contains a motif found at the active site of disulfide oxidoreductases in the thioredoxin family. This, plus the ability of the R. capsulatus CcmG homologue to form an intramolecular disulfide bond (26), has been taken as provisional evidence that this protein has disulfide oxidoreductase activity. Thus, it is not surprising that supplementing growth media with low-molecular-weight thiols (cysteine, cystine, 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid, or dithiothreitol) can partially rescue CcmG mutants in some species (6, 15, 20), presumably because these thiols substitute for the proposed disulfide oxidoreductase activity of this protein. Adding cysteine, cystine, or dithiothreitol to media did not enable us to generate a strain lacking CcmG using either ccmG1::spc or the ccmA1::spc allele that should block expression of ccmBCDG (data not shown).

The inability to obtain cells lacking CcmG could also reflect a low frequency of recombination in this region. To increase the probability of finding cells that arise from possibly rare recombination events, Tcr cells containing either the ccmA1::spc or ccmG1::spc allele and a wild-type ccmABCDG locus (CCMA2 and CCMG2, respectively) were grown aerobically for ∼20 generations in antibiotic-free media prior to screening for markers linked to the ccm mutation (Spr) or the suicide plasmid (Tcr). After screening ∼20,000 independent CCMA2 (ccmA1::spc) or ∼40,000 CCMG2 (ccmG1::spc) colonies, no cells were found that had lost the suicide plasmid while retaining the mutant ccm allele (Tcs Spr; Table 2). This procedure resulted in the generation of numerous cytochrome c2 mutants using a strain that contains both a cycA1::kan allele and a wild-type cycA gene (Table 2). When the failure to isolate cells lacking CcmG at a reasonable frequency in controlled experiments is considered, it leads us to consider the possibility that this protein plays a role in some other important cellular process.

TABLE 2.

Use of a merodiploid to generate null mutations at ccmABCDG or cycA

| Strain/gene | No. of colonies found with genotype:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of function (Tcs) | Merodiploid (Spr Tcr) | Wild type (Sps Tcs) | |

| CYCA2/cycA | 24,913 | 42 | 45 |

| CCMG2/ccmG | 0 | 39,985 | 15 |

| CCMA2/ccmA | 0 | 19,956 | 44 |

What additional functions might CcmG provide R. sphaeroides?

If CcmG is a disulfide oxidoreductase, there are several reasons why R. sphaeroides might need such a periplasmic activity for purposes in addition to c-type cytochrome maturation. R. sphaeroides is believed to require a functional electron transport chain since it cannot generate sufficient energy to grow solely by substrate-level phosphorylation (25). Thus, one possibility is that CcmG also aids assembly of another respiratory enzyme. Indeed, a Paracoccus denitrificans ΔCcmG mutant contains reduced levels of the cytochrome aa3 complex (19). Of the five terminal oxidases believed to be encoded in the R. sphaeroides genome, four of these enzymes are known or presumed to contain c- or a-type heme (http://genome.ornl.gov/microbial/rsph/). Thus, loss of CcmG could prevent R. sphaeroides from producing sufficient quantities of one or more terminal oxidases that are required to support respiration under our laboratory conditions. It is also possible that CcmG acts in a general pathway for the assembly of other periplasmic enzymes, in a manner reminiscent of the Dsb-dependent folding of extracytoplasmic proteins (23). In this regard, there is evidence that the CcmG homologue of E. coli interacts with DsbD (10). The cytoplasmic disulfide oxidoreductase, thioredoxin, is essential in R. sphaeroides (21), so this α-proteobacterium may also have roles for a periplasmic disulfide oxidoreductase that are more far-reaching than those in well-studied enteric bacteria (23).

In summary, the R. sphaeroides ccmABCDG gene cluster is generally similar to those found in other α-proteobacteria. CcmA is required for c-type cytochrome maturation, but it appears that CcmG has a function outside its commonly accepted role in the assembly of these electron carriers. In the future, mutants lacking CcmA or other Ccm proteins will facilitate determining how they function in c-type cytochrome maturation. These strains will also help identify components of this bacterium's aerobic respiratory chain and dissect the pathway that couples aerobic electron transport to global changes in gene expression (18).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant GM37509 to T.J.D.

We thank R. Kranz for supplying R. capsulatus ccm probes and T. Pastjin for help in constructing mutants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bethesda Research Laboratories. BRL pUC host: Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells. Bethesda Res Lab Focus. 1986;8:9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donohue T J, Kaplan S. Genetic techniques in Rhodospirillaceae. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:459–485. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04024-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donohue T J, McEwan A G, Kaplan S. Cloning, DNA sequence, and expression of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome c2 gene. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:962–972. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.962-972.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donohue T J, McEwan A G, Van Doren S, Crofts A R, Kaplan S. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of cytochrome c2 deficient mutants of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 1988;27:1918–1925. doi: 10.1021/bi00406a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dryden S C, Kaplan S. Localization and structural analysis of the ribosomal RNA operons of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7267–7277. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabianek R A, Hennecke H, Thony-Meyer L. The active-site cysteines of the periplasmic thioredoxin-like protein CcmG of Escherichia coli are important but not essential for cytochrome c maturation in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1947–1950. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1947-1950.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fellay R, Frey J, Krisch H. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA fragments designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1987;52:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flory J E, Donohue T J. Organization and expression of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cycFG operon. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4311–4320. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4311-4320.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaballa A, Koedam N, Cornelis P. A cytochrome c biogenesis gene involved in pyoverdine production in Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 17400. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:777–785. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.391399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katzen F, Beckwith J. Transmembrane electron transfer by the membrane protein DsbD occurs via a disulfide bond cascade. Cell. 2000;103:769–779. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keen N T, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1988;70:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kranz R G. Isolation of mutants and genes involved in cytochromes c biosynthesis in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:456–464. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.456-464.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kranz R G, Beckman D L. Cytochrome biogenesis. In: Blankenship R E, Madigan M T, Bauer C E, editors. Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Dordecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 709–723. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenz O, Schwartz E, Dernedde J, Eitinger M, Friedrich B. The Alcaligenes eutrophus H16 hoxX gene participates in hydrogenase regulation. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4385–4393. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.14.4385-4393.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monika E M, Goldman B S, Beckman D L, Kranz R G. A thioreduction pathway tethered to the membrane for periplasmic cytochromes c biogenesis; in vitro and in vivo studies. J Mol Biol. 1997;271:679–692. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mouncey N J, Choudhary M, Kaplan S. Characterization of genes encoding dimethyl sulfoxide reductase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1T: an essential metabolic gene function encoded on chromosome II. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7617–7624. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7617-7624.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh J I, Kaplan S. The cbb3 terminal oxidase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: structural and functional implications for the regulation of spectral complex formation. Biochemistry. 1999;38:2688–2696. doi: 10.1021/bi9825100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh J I, Kaplan S. Generalized approach to the regulation and integration of gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:1116–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2001.02299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page M D, Ferguson S J. Mutational analysis of the Paracoccus denitrificans c-type cytochrome biosynthetic genes ccmABCDG: disruption of ccmC has distinct effects suggesting a role for CcmC independent of CcmAB. Microbiology. 1999;145:3047–3057. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-11-3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page M D, Pearce D A, Norris H A, Ferguson S J. The Paracoccus denitrificans ccmA, B and C genes: cloning and sequencing, and analysis of the potential of their products to form a haem or apo- c-type cytochrome transporter. Microbiology. 1997;143:563–576. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasternak C, Assemat K, Clement-Metral J D, Klug G. Thioredoxin is essential for Rhodobacter sphaeroides growth by aerobic and anaerobic respiration. Microbiology. 1997;143:83–91. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pettigrew G W, Moore G R. Cytochromes c: biological aspects. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rietsch A, Beckwith J. The genetics of disulfide bond metabolism. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:163–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schultz J E, Weaver P F. Fermentation and anaerobic respiration by Rhodospirillum rubrum and Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:181–190. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.1.181-190.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Setterdahl A T, Goldman B S, Hirasawa M, Jacquot P, Smith A J, Kranz R G, Knaff D B. Oxidation-reduction properties of disulfide containing properties of the Rhodobacter capsulatus cytochrome c biogenesis system. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10172–10176. doi: 10.1021/bi000663t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vitro genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:748–791. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sistrom W R. A requirement for sodium in the growth of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. Gen Microbiol. 1960;22:778–785. doi: 10.1099/00221287-22-3-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suwanto A, Kaplan S. Physical and genetic mapping of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 genome: presence of two unique circular chromosomes. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5850–5859. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.5850-5859.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas P E, Ryan D, Levin W. An improved staining procedure for the detection of the peroxidase activity of cytochrome P-450 on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1976;75:168–176. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thony-Meyer L. Biogenesis of respiratory cytochromes in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:337–376. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.337-376.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]