Abstract

Background

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is a clinical syndrome resulting from loss of ovarian function before the age of 40. It is a state of hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, characterised by amenorrhoea or oligomenorrhoea, with low ovarian sex hormones (oestrogen deficiency) and elevated pituitary gonadotrophins. POI with primary amenorrhoea may occur as a result of chromosomal and genetic abnormalities, such as Turner syndrome, Fragile X, or autosomal gene defects; secondary amenorrhoea may be iatrogenic after the surgical removal of the ovaries, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. Other causes include autoimmune diseases, viral infections, and environmental factors; in most cases, POI is idiopathic. Appropriate replacement of sex hormones in women with POI may facilitate the achievement of near normal uterine development. However, the optimal effective hormone therapy (HT) regimen to maximise the reproductive potential for women with POI remains unclear.

Objectives

To investigate the effectiveness and safety of different hormonal regimens on uterine and endometrial development in women with POI.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility (CGF) Group trials register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and two trials registers in September 2021. We also checked references of included studies, and contacted study authors to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effect of various hormonal preparations on the uterine development of women diagnosed with POI.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures recommended by Cochrane. The primary review outcome was uterine volume; secondary outcomes were endometrial thickness, endometrial histology, uterine perfusion, reproductive outcomes, and any reported adverse events.

Main results

We included three studies (52 participants analysed in total) investigating the role of various hormonal preparations in three different contexts, which deemed meta‐analysis unfeasible. We found very low‐certainty evidence; the main limitation was very serious imprecision due to small sample size.

Conjugated oral oestrogens versus transdermal 17ß‐oestradiol

We are uncertain of the effect of conjugated oral oestrogens compared to transdermal 17ß‐oestradiol (mean difference (MD) ‐18.2 (mL), 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐23.18 to ‐13.22; 1 RCT, N = 12; very low‐certainty evidence) on uterine volume, measured after 12 months of treatment. The study reported no other relevant outcomes (including adverse events).

Low versus high 17ß‐oestradiol dose

We are uncertain of the effect of a lower dose of 17ß‐oestradiol compared to a higher dose of 17ß‐oestradiol on uterine volume after three or five years of treatment, or adverse events (1 RCT, N = 20; very low‐certainty evidence). The study reported no other relevant outcomes.

Oral versus vaginal administration of oestradiol and dydrogesterone

We are uncertain of the effect of an oral or vaginal administration route on uterine volume and endometrial thickness after 14 or 21 days of administration (1 RCT, N = 20; very low‐certainty evidence). The study reported no other relevant outcomes (including adverse events).

Authors' conclusions

No clear conclusions can be drawn in this systematic review, due to the very low‐certainty of the evidence.

There is a need for pragmatic, well designed, randomised controlled trials, with adequate power to detect differences between various HT regimens on uterine growth, endometrial development, and pregnancy outcomes following the transfer of donated gametes or embryos in women diagnosed with POI.

Plain language summary

Which hormonal therapy works better for women with early failure of the ovaries?

Key messages

We only found three studies that looked at a variety of hormonal therapies in three different contexts.

Based on the data from these small studies, we were unable to draw any clear conclusions.

There is a need for adequately performed and sufficiently large studies to research the best hormonal therapies for women with early failure of the ovaries, in order to improve their chances of having a healthy pregnancy.

What is early failure of the ovaries?

Ovaries are a pair of glands that respond to, and produce hormones, such as oestrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. They have important roles in bone, heart, and reproductive health. Early failure of the ovaries is a condition affecting about 1% of women, by depriving them of the normal hormones produced by the ovaries. This then increases their risk of bone fractures, heart disease, and infertility. Early failure of the ovaries might be diagnosed if a girl's first period has not started by the age of 16 years, or if a woman misses her period for more than six months before the age of 40 years. Blood tests are also needed to confirm the abnormal levels of the various hormones, which are related to how ovaries work.

How is early failure of the ovaries treated?

Early failure of the ovaries is generally treated with hormone therapies, which imitate what normal working ovaries would ordinarily have produced. The aim of the treatment is to balance the negative effects of this condition on the bones, heart, and blood vessels, and on reproductive health. The treatments may include different hormones administered at different doses, by either mouth, skin patches, injections, or vaginally.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out the best combination of hormones that would allow women to have a baby after they suffered from early failure of the ovaries. We also wanted to find out the unwanted effects of the hormone treatments used to treat early failure of the ovaries.

What did we do?

We followed standard Cochrane methods to search for studies, compare and summarise the results of the studies, and rate our confidence in the evidence, based on factors, such as study methods and study sizes.

What did we find?

We found three studies that recruited a total of 52 women with early failure of the ovaries. We are uncertain of the effect of any hormonal therapy when compared to the others.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

The main limitation was the small number of studies, which had very small numbers of women in each study (ranged from 12 to 20 women in each one).

How up to date is the evidence?

The evidence is up to date to September 2021.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), also called premature ovarian failure, is a clinical syndrome resulting from the loss of ovarian function before the age of 40. It is characterised by amenorrhoea or oligomenorrhoea, with low ovarian sex hormones (oestrogen deficiency) and elevated pituitary gonadotrophins. It is a state of hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. A reference age of 40 years is used as an arbitrary limit, based on clinical observation and statistical calculation – the age of 40 is two standard deviations below the mean age of menopause for the reference population (50 ± 4 years). POI occurs in 1% of the female population (Coulam 1986; Krailo 1983); however, ethnicity (Luborsky 2003), lifestyle factors (Baron 1984; Sun 2012; van Noord 1997), and socioeconomic factors (Kuh 2005; Whalley 2004), can influence the prevalence.

POI can present as primary amenorrhoea before attaining menarche, or as secondary amenorrhoea or oligomenorrhoea. Secondary amenorrhoea or oligomenorrhoea for at least four to six months, and two high follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH) levels (> 25 mIU/mL) measured at least four weeks apart are used to diagnose (ESHRE 2016; La Marca 2006).

POI with primary amenorrhoea may occur as a result of chromosomal and genetic abnormalities, such as Turner syndrome, Fragile X, or autosomal gene defects. Turner syndrome is the most common sex chromosome disorder among women, affecting 1 in 2000 liveborn girls (Gravholt 1996). The main characteristics of Turner syndrome include short stature, and failure to enter puberty, due to inadequate or absent ovarian function (Guttmann 2001).

POI with secondary amenorrhoea may be iatrogenic after the surgical removal of the ovaries, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. Other causes include autoimmune diseases, viral infections, and environmental factors; in most cases, POI is idiopathic. More than 70% of children treated for cancer are cured by irradiation and chemotherapy (Mertens 2001), resulting in an increased number of children presenting with pubertal failure or POI, due to irreversible damage to ovarian function (Critchley 2002; Larsen 2004; Wallace 1989).

POI caused by autoimmunity involves inflammatory infiltration of developing follicles, production of anti‐ovarian antibodies, atrophy, and sparing of primordial follicles (Melner 1999). Various infections, including mumps, HIV, herpes zoster, cytomegalovirus, tuberculosis, malaria, varicella, and shigella can be related to POI, but no studies have demonstrated any direct cause or effect (Goswami 2007; Kokcu 2010). The menopausal signs and symptoms in non‐iatrogenic POI have a gradual onset compared to iatrogenic POI, in which case the onset is immediate, due to the acute lack of oestrogen (Jacoby 2011; Parker 2009; Rocca 2006; Shuster 2010).

In addition to fertility issues, women with POI have more health problems, such as osteoporosis, cardiovascular, and neurological diseases. All of these long‐term complications contribute to premature mortality in women diagnosed with POI.

Description of the intervention

Various preparations of hormonal therapy (HT) are prescribed for women with POI, including the combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill. In prepubescent girls, the dose and duration of HT prescribed to mimic puberty is usually adjusted according to the young woman's height and the Tanner stage of development (Hovatta 1999). Thereafter, they are usually prescribed a low‐dose COC; they often continue on the same regimen for several years. Older women with POI are often prescribed either COC or a combined HT preparation.

The most common aim of prescribing HT for women with POI is to relieve vasomotor symptoms, and reduce the risk of osteoporosis. The optimal effective HT regime to maximise the reproductive potential for women with POI remains unclear, due to a paucity of evidence to support the preferential effectiveness of the different regimens used. In Turner syndrome, women may respond differently to HT in uterine development, depending on the karyotype (Doerr 2005).

Assisted reproduction using donated oocytes or embryos is the only realistic treatment option for women with POI, with an average clinical pregnancy rate of approximately 40% per cycle started (Bodri 2006; Foudila 1999). Even with donated oocytes, the success rate depends on the uterine and endometrial development, which can be influenced by the dose and type of HT, as well as the age at which HT was commenced to induce puberty (McDonnell 2003).

The role of HT has been emphasised for normal development of the genital tract, and its effect on the reproductive potential for women with POI (Meskhi 2006). Some investigators have determined that a normal uterine size essential for a successful pregnancy has a minimum length of 5 cm, a sagittal width of 1.5 cm to 3 cm, and transverse width of 3 cm to 5 cm (McDonnell 2003). An endometrial thickness of 6.5 mm or more is necessary for successful implantation (Abdalla 1994).

In postmenopausal women, hormone replacement therapy has been linked to increased risks of coronary heart disease (Grady 2002; Rossouw 2007), stroke (Hendrix 2006; Wassertheil‐Smoller 2003), venous thrombosis (Peverill 2003; Scarabin 2003), and endometrial (Beral 2005), breast (Shah 2005), and ovarian cancers (Beral 2007). Evidence for the risks of HT in women with POI is limited. However, the baseline risk of adverse events in younger women is lower, and the balance of benefits and risks may be more favourable than in older women (MHRA 2007). Some evidence has emerged that the side effects can be reduced by modifying the route of administration. The transdermal route has been proven to reduce the side effects in young women with POI (Torres‐Santiago 2013).

How the intervention might work

The bulk of the human uterus is formed by the myometrium, which consists of smooth muscle. The distinct proliferation and differentiation of the smooth muscle cells depend on ovarian hormonal secretion (Andreyko 1988; Demas 1986; McCarthy 1986). The presence of oestrogen receptors in myometrial smooth muscle cells signal the complex interactions between ovarian hormones and various growth factors (cytokines, platelet‐derived growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, epidermal growth factor, and insulin‐like growth factors), which are responsible for the development and maturation of the uterus.

The endometrium is a complex multicellular tissue that lines the intrauterine cavity. It plays a crucial role in reproduction, due to its essential interaction with the blastocyst (Craciunas 2019). It has the unique capability of undergoing dynamic remodelling by proliferation and differentiation processes controlled by the ovarian steroid hormones (Craciunas 2021). Endometrial epithelial cells are stimulated by 17ß‐oestradiol and epidermal growth factors (Zhang 1995). Uterine underdevelopment occurs in the absence of sex hormones in women with POI (Hovatta 1999). Appropriate replacement of sex hormones in women with POI may facilitate the achievement of near normal uterine development. Evidence suggests that adult endometrial tissue contains epithelial progenitor and mesenchymal/stromal cells that could be the target of specific HT, to regenerate the endometrial tissue in cases of a dysfunctional or atrophic endometrium (Kelleher 2019).

Why it is important to do this review

There is currently no robust evidence about the fertility role of HT regimens in women with POI. These treatments have not been extensively evaluated for their effectiveness in attaining normal uterine growth and achieving optimum endometrial function, which are essential for successful reproductive outcomes. There is also a lack of consensus on the optimal type, dosage, and duration of HT in this population of women.

In the absence of strong evidence from individual studies, undertaking a systematic review offers an overview of the current knowledge, and identifies gaps that require further research.

Objectives

To investigate the effectiveness and safety of different hormonal regimens on uterine and endometrial development in women with premature ovarian insufficiency.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for inclusion. Cross‐over trials were excluded because of the long‐term effect of hormone therapy (HT) on the uterine dimensions.

Types of participants

All women with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) due to any cause, including surgically‐induced POI, were eligible for inclusion, whether the women were trying to conceive or not. POI was defined as primary or secondary amenorrhoea associated with high levels of follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH > 40 IU/L) on two occasions, in women younger than 40 years. Primary amenorrhoea was defined as the absence of menstruation by the age of 16 years. Secondary amenorrhoea was defined as cessation of menstruation for more than six months.

Types of interventions

We planned to compare different hormonal regimens in women with POI with each other, with a placebo, or with no treatment. Hormonal regimens, using any route, may have included the following.

Oestradiol: unopposed, or as commonly used in hormone replacement therapy preparations, which is in combination with various progestogens in sequential or continuous regimens

Conjugated equine oestrogen: unopposed, or as commonly used in hormone replacement therapy preparations, which is in combination with various progestogens in sequential or continuous regimens

Ethinyl oestradiol: unopposed, or as commonly used in oral contraceptives, which is in combination with various progestogen preparations

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Uterine volume: measured by ultrasound (to reflect reproductive potential); calculated by using the formula: volume (mL) = transverse width x sagittal width x length x 0.5.

Secondary outcomes

One or more of the following parameters achieved after hormonal treatment.

Endometrial thickness: measured in the longitudinal plane of the uterus, using transvaginal or transabdominal ultrasound scan, as the maximal distance (in millimetres) between the myometrial‐endometrial junction on either side of the uterine cavity

Endometrial histology: assessed by the presence of features similar to secretory endometrium on endometrial biopsy in the mid‐luteal phase

Uterine perfusion: assessed by the pulsatility index, which is the difference between the peak‐systolic and the end‐diastolic velocities divided by mean velocity, using pulsed Doppler ultrasound

Reproductive outcomes in women with POI who received donated eggs or embryos (fresh or frozen): pregnancy rate per cycle started or per embryo transfer, clinical pregnancy rate per cycle started or per embryo transfer, and live birth rate per cycle started or per embryo transfer. We defined clinical pregnancy as the visualisation of a gestational sac by ultrasound scan, at six to seven weeks' gestation.

Any adverse events reported

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all RCTs that described (or seemed to describe) RCTs of hormonal treatments or therapies in women with POI, in consultation with the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group (CGF) Information Specialist.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

The Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group's (CGFG) specialised register of controlled trials, ProCite platform (searched 27 September 2021; Appendix 1);

CENTRAL via the Cochrane Central Register of Studies Online (CRSO; searched 27 September 2021; Appendix 2);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 27 September 2021; Appendix 3);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 27 September 2021; Appendix 4);

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to 27 September 2021; Appendix 5);

CINAHL EBSCO (1960 to 4 June 2020; Appendix 6; CINAHL records are now incorporated into CENTRAL).

We combined the MEDLINE search with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials. We combined the Embase and CINAHL searches with trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN; www.sign.ac.uk/what-we-do/methodology/search-filters/). The PsycINFO search filter was developed by the Health Information Research Unit, McMaster University (hiru.mcmaster.ca/hiru/HIRU_Hedges_PsycINFO_Strategies.aspx).

We searched the Epistemonikos database for systematic reviews that could be useful to check references for trials on 10 October 2021 (/www.epistemonikos.org/en).

The CRSO now contains trial registry records from the US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; trialsearch.who.int/) to identify ongoing and registered trials.

We also searched OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu/), and Google Scholar (scholar.google.co.uk/), on 10 October 2021 for grey (i.e. unpublished) literature.

Searching other resources

We handsearched reference lists of relevant articles retrieved by the searches, and contacted experts in the field to search for additional trials.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection and analysis was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021).

Selection of studies

Three of the authors (LC, NZ, SV) independently reviewed the titles, abstracts, and full‐text studies in accordance with the selection criteria. We planned to resolve disagreements by consensus, and by the involvement of a fourth review author (LM) as required.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data from eligible studies, using a data extraction form designed and pilot tested by the authors. When studies had multiple publications, we planned to use the main trial report as the reference, and extract additional details from the secondary papers. Two authors (LC, NZ) independently extracted the data. We planned to correspond with study investigators if required.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias in the included studies using the Cochrane RoB 1 assessment tool for: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, providers, and outcome assessors; completeness of outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other potential sources of bias (Higgins 2017). We planned to take particular note of the baseline characteristics of women in the comparable groups. Two authors (LC, NZ) independently assessed these six domains, with any disagreements resolved by consensus or by discussion with a third author (LM). All judgements were fully described. We presented the conclusions in the risk of bias tables, and incorporated them into the interpretation of review findings with sensitivity analyses (see below).

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data (for example endometrial histology), we planned to use the number of events in the control and intervention groups of each study to calculate Peto odds ratios. For continuous data (for example uterine volume or endometrial thickness), we planned to calculate mean differences between treatment groups if all studies reported exactly the same outcomes. If similar outcomes were reported on different scales (for example change in uterine length, change in uterine volume), we planned to use the standardised mean difference.

Unit of analysis issues

For the primary analysis, we planned to use women randomised. We planned to briefly summarise data that did not allow valid analysis (by cycle data) in an additional table, and did not plan to meta‐analyse them. We planned to count multiple live births (twins or triplets) as one live‐birth event.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to analyse the data on an intention‐to‐treat basis as far as possible, and attempt to obtain missing data from the original investigators as needed. When these were unobtainable, we planned to impute individual values for the primary outcome only. We did not plan to assume that a change in uterine volume or length occurred in participants with unreported outcome.

If studies reported sufficient detail to calculate mean differences, but no information on associated standard deviation (SD), we planned to assume that the outcome had an SD equal to the highest SD from other studies within the same analysis.

For other outcomes, we planned to only analyse the available data. We planned to subject any imputation undertaken to a sensitivity analysis (see below).

Assessment of heterogeneity

The authors considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a meaningful summary. We planned to assess statistical heterogeneity with the I² statistic. An I² statistic greater than 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2021). If we detected substantial heterogeneity, we planned to explore possible explanations in sensitivity analyses (see below).

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty in detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, the review authors aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies, and by being alert for duplication of data. If there were 10 or more studies in an analysis, they planned to use a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small study effects (a tendency for the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies).

Data synthesis

We planned to combine the data from primary studies using a fixed‐effect model, in the following comparisons.

-

Oestradiol, unopposed, or in combination with various progestogens in a sequential or a continuous regimen versus placebo or no treatment, stratified by mode of administration and dose:

low‐dose oral;

high‐dose oral;

low‐dose subcutaneous;

high‐dose subcutaneous;

low‐dose transdermal;

high‐dose transdermal.

-

Oestradiol versus alternative oestrogen therapy, stratified by:

conjugated equine oestrogen;

ethinyl oestradiol.

-

3. Oestradiol (low‐dose) versus oestradiol (high‐dose), stratified by mode of administration.

oral

subcutaneous

-

4. Oestradiol (oral) versus oestradiol (subcutaneous), stratified by:

low‐dose;

high‐dose.

We planned to display an increase in the odds of a particular outcome, which may have been beneficial (for example increase in uterine volume) or detrimental (for example adverse effects), graphically in the meta‐analyses to the right of the centre line and a decrease in the odds of an outcome to the left of the centre line.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where data were available, we planned to undertake subgroup analyses to determine the evidence within the following subgroups.

Pregnancy and live birth rates of women with POI undergoing donated oocyte or embryo replacement

Studies on young adolescents with an average age less than 20 years

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to undertake sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome to determine whether the conclusions were robust with the arbitrary decisions made regarding the eligibility and analysis. These analyses were planned to consider whether conclusions would have differed if:

eligibility was restricted to studies without high risk of bias (no high risk in any domain);

studies with outlying results had been excluded;

alternative imputation strategies had been adopted;

a random‐effects model had been adopted.

We planned to include trials that used a different definition for POI, and assess the quality of the definitions with a sensitivity analysis.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We prepared a summary of findings (SoF) table that included all review outcomes, for every comparison, using GRADEpro GDT (GRADEpro GDT). The SoF tables evaluated the overall certainty of the body of evidence in the comparison of various HT preparations for each outcome, using GRADE criteria. Two review authors (LC, NZ) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence, based on five GRADE factors: study limitations (i.e. risk of bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias, as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (McKenzie 2022). We justified, documented, and incorporated our judgements about the certainty of the evidence (high, moderate, low, or very low) into the reporting of results for each outcome.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables for details.

Results of the search

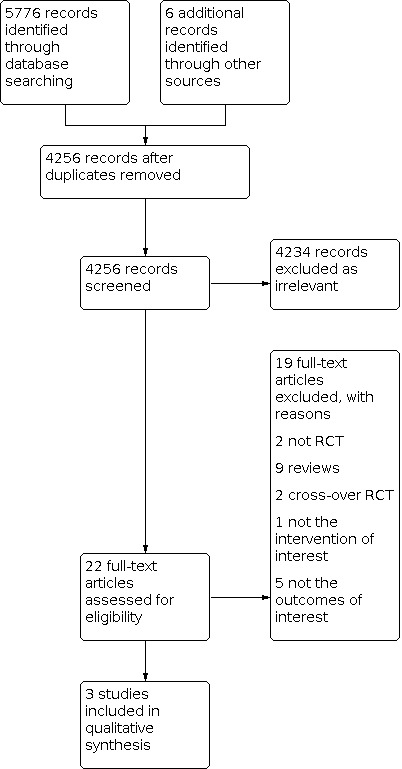

We performed the latest systematic search on 27 September 2021, and identified 5782 publications (5776 through databases search, 6 from other sources). See Figure 1 for detailed search results.

1.

Study PRISMA flow diagram

Included studies

Three studies were eligible for inclusion and contributed to the qualitative synthesis (Cleemann 2020; Feng 2021; Nabhan 2009). They investigated different populations, interventions, comparisons, and outcome (PICO) questions, and were not eligible for meta‐analysis.

Nabhan 2009 was a parallel‐arm randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted in the USA, and was published as a full manuscript. It reported funding by a national charity grant.

Cleemann 2020 was a parallel‐arm RCT conducted in Denmark, and was published as a full manuscript. It reported funding by local grants; national foundations; and Novo Nordisk, which provided the study medicine.

Feng 2021 was a parallel‐arm RCT conducted in China, and was published as a full manuscript. It reported funding by local and national grants.

Participants

Nabhan 2009 included 12 girls diagnosed with Turner syndrome, aged 11 years to 17 years, who were naive to oestrogen and on growth hormone therapy for at least six months.

Cleemann 2020 included 20 women diagnosed with Turner syndrome confirmed by karyotyping, aged 16 years to 25 years, who had completed their pubertal induction and reached their final height after completing growth hormone treatment.

Feng 2021 included 20 women diagnosed with POI, aged 20 years to 35 years, and awaiting oocyte donation. POI was diagnosed based on four to six months of amenorrhoea; FSH concentrations > 40 mIU/mL at least twice, at an interval of four to six weeks; oestradiol concentrations < 20 pg/mL; and endometrium with a double‐wall thickness < 5 mm. They also had a normal uterine cavity, and had taken no steroid replacement drug treatment in the previous three months.

Interventions

Nabhan 2009 randomised young women to receive conjugated oral oestrogen (conjugated oestrogen, Premarin; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, PA) or transdermal oestradiol (17ß‐oestradiol, Vivelle TD system; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, East Hanover, NJ) for one year. Conjugated oral oestrogen was administered at a dose of 0.3 mg every day for the first six months, followed by 0.3 mg alternating with 0.625 mg every day for the second six months. The transdermal oestradiol group was treated with a 0.025 mg patch twice a week for six months, followed by a 0.0375 mg patch twice a week for the second six months.

Cleemann 2020 randomised women to receive either a lower or a higher dose of 17ß‐oestradiol. The lower dose group took Trisekvens orally (2 mg 17ß‐oestradiol/day for days 1 to 12, 2 mg 17ß‐oestradiol/day and 1 mg norethisterone acetate/day for days 13 to 22, and 1 mg 17ß‐oestradiol/day for days 23 to 28; Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark), combined with placebo on days 1 through 22 of the menstrual cycle. The higher dose group took Trisekvens orally combined with oestradiol 2 mg (Novo Nordisk) on days 1 through 22 of the menstrual cycle.

Feng 2021 randomised women into equal groups to receive endometrial preparation using either oral or vaginal preparations. The oral preparations consisted of femoston 2/10 sequentially (Abbott Biologicals B.V, Weesp, Netherlands), which comprised 14 red pills containing 2 mg oestradiol, 14 yellow pills containing 2 mg oestradiol and 10 mg dydrogesterone. The vaginal preparations consisted of femoston 1/10, which comprised 14 white pills containing 1 mg oestradiol, and 14 grey pills containing 1 mg oestradiol and 10 mg dydrogesterone. The women did not undergo embryo transfer during the study.

Outcomes

Nabhan 2009 reported on uterine volume after 12 months of treatment.

Cleemann 2020 reported on uterine volume after three and five years of treatment.

Feng 2021 reported on uterine volume and endometrial thickness after 14 and 21 days of treatment.

Excluded studies

We excluded 19 studies because they: were not RCTs (Achiron 1995; Snajderova 2003), were reviews (Ben‐Naghi 2014; Burgos 2017; Fraison 2019; Gelbaya 2011; Kasteren 1999; Liu 2019; Robles 2013; Sullivan 2016; Webber 2017), were cross‐over RCTs (Li 1992; O'Donnell 2012), did not investigate the intervention of interest (Badawy 2007), and did not report the outcomes of interest (Benetti‐Pinto 2020; Gault 2011; Labarta 2012; Ross 2011; Tartagni 2007).

We did not identify any studies awaiting classification, and we found no ongoing studies in trial databases.

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 shows the risk of bias graph, and Figure 3 shows the risk of bias summary. See the Characteristics of included studies table for rationales behind each judgement.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

All three included studies were reported as RCTs, but only Nabhan 2009 provided details about the randomisation process, and we judged it at low risk of selection bias. The remaining two included studies provided no randomisation details, and we judged them as unclear risk of selection bias.

None of the three included studies provided details on allocation concealment, and we judged them as unclear risk of selection bias.

Blinding

None of the three included studies provided details on blinding of participants and personnel, but we judged them at low risk of performance bias due to the non‐subjective nature of the outcomes.

Feng 2021 reported blinding of ultrasound assessors, and we judged it at low risk of detection bias. The remaining two included studies provided no details on the blinding of outcome assessors, and we judged them as unclear risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Cleemann 2020 reported that 4 out of 20 study participants did not complete follow‐up, and we judged it at high risk of attrition bias; the remaining two included studies followed up on all participants, and we judged them at low risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

All three included studies reported on outcomes relevant to their respective PICO question, and we judged them at low risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify any other potential sources of bias for either of the three included studies; we judged all of them at low risk of other bias (Cleemann 2020; Feng 2021; Nabhan 2009).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings 1. Conjugated oral oestrogens compared to transdermal 17ß‐estradiol in girls with Turner syndrome.

| Conjucted oral oestrogens compared to transdermal 17ß‐estradiol in girls with Turner syndrome | ||||

| Patient or population: girls with Turner syndrome who were treated with prepubertal growth hormone Setting: endocrinology clinic Intervention: conjugated oral oestrogens Comparison: transdermal 17ß‐oestradiol | ||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Difference with transdermal 17ß‐estradiol | Difference with conjugated oral oestrogens | |||

| Uterine volume (mL)(measured after 12 months) | ‐ | MD 18.2 lower (23.18 lower to 13.22 lower) | 12 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b |

| Endometrial thickness | Outcome not reported | |||

| Endometrial histology | Outcome not reported | |||

| Uterine perfusion | Outcome not reported | |||

| Reproductive outcomes | Outcome not reported | |||

| Adverse events | Outcome not reported | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||

aDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: high risk of detection bias due to lack of blinding of outcome assessors and unclear risk of selection bias due to unclear allocation concealment bDowngraded two levels for serious imprecision: single site study with a sample size of 12 participants

Summary of findings 2. Low versus high 17ß‐oestradiol dose in women with Turner syndrome.

| Conjucted oral oestrogens compared to transdermal 17ß‐estradiol in women with Turner syndrome | |||

| Patient or population: young women with Turner syndrome who have completed pubertal induction Setting: pediatrics clinic Intervention: high dose 17ß‐oestradiol Comparison: low dose 17ß‐oestradiol | |||

| Outcomes | Difference between low dose versus high dose | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Uterine volume (mL)(measured after 3 years) | Trial authors reported a higher gain in uterine volume in the high dose group compared to the low dose group. | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b |

|

Uterine volume (mL) (measured after 5 years) |

Trial authors reported no difference in the change of uterine volume between the high dose and low dose groups. | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b |

| Endometrial thickness | Outcome not reported | ||

| Endometrial histology | Outcome not reported | ||

| Uterine perfusion | Outcome not reported | ||

| Reproductive outcomes | Outcome not reported | ||

| Adverse events | One of the 10 participants included in the high dose group withdrew from the study in the first year, due to oedema of the lower limbs. | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

aDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: high risk of attrition bias because 4 out of 10 participants in the high dose group were lost to follow‐up, unclear risk of selection bias due to unclear randomisation technique and allocation concealment, and unclear risk of detection bias due to unclear blinding of assessors bDowngraded two levels for serious imprecision: single site study with a sample size of 20 participants

Summary of findings 3. Oral versus vaginal administration of oestradiol and dydrogesterone in women diagnosed with premature ovarian insufficiency.

| Oral versus vaginal administration of oestradiol and dydrogesterone in women diagnosed with premature ovarian insufficiency | |||

| Patient or population: women with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) awaiting oocyte donation Setting: assisted reproduction clinic Intervention: vaginal administration of oestradiol and dydrogesterone Comparison: oral administration of oestradiol and dydrogesterone | |||

| Outcomes | Risk with oral versus vaginal administration | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Uterine volume (mL)(measured after 14 days) | Trial authors reported no difference in the change of uterine volume between the oral and vaginal administration groups after 14 days. | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b |

| Uterine volume (mL)(measured after 21 days) | Trial authors reported no difference in the change of uterine volume between the oral and vaginal administration groups after 21 days. | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b |

| Endometrial thickness (mm)(measured after 14 days) | Trial authors reported a higher increase in endometrial thickness in the vaginal administration compared to oral administration groups after 14 days. | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b |

| Endometrial thickness (mm)(measured after 21 days) | Trial authors reported a higher increase in endometrial thickness in the vaginal administration compared to oral administration groups after 21 days. | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b |

| Endometrial histology | Outcome not reported | ||

| Uterine perfusion | Outcome not reported | ||

| Reproductive outcomes | Outcome not reported | ||

| Adverse events | Outcome not reported | ||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

aDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: unclear risk of selection bias due to unclear randomisation technique and allocation concealment bDowngraded two levels for serious imprecision: single site study with a sample size of 20 participants

Conjugated oral oestrogens versus transdermal 17ß‐oestradiol

One study recruited girls aged 10 years and older who were naive to oestrogen and on growth hormone therapy for at least six months (Nabhan 2009). See Table 1.

Primary outcome

Uterine volume (mL) measured after 12 months of treatment:

We are uncertain of the effect of conjugated oral oestrogens compared to transdermal 17ß‐oestradiol (mean difference (MD) ‐18.2, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐23.18 to ‐13.22; 1 RCT, N = 12; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Conjugated oral oestrogens versus transdermal 17ß‐estradiol, Outcome 1: Uterine volume (mL)

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Conjucted oral oestrogens versus transdermal 17ß‐estradiol, outcome: 1.1 Uterine volume (mL)

Data were insufficient for subgroup or sensitivity analyses.

Secondary outcomes

No study reported on any of the secondary outcomes.

Low versus high 17ß‐oestradiol dose

One study recruited 10 women with Turner syndrome diagnosed by previous karyotyping, who achieved final height, growth hormone treatment, and pubertal induction (Cleemann 2020). See Table 2.

Primary outcome

Uterine volume (mL) measured after three years of treatment

There were insufficient data for statistical analyses. Trial authors reported a higher gain in uterine volume in the high dose group compared to the low dose group.

Uterine volume (mL) measured after 5 years of treatment

There were insufficient data for statistical analyses. Trial authors reported no difference in the change of uterine volume between the high dose and low dose groups.

Data were insufficient for subgroup or sensitivity analyses.

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events

One out of the 10 participants included in the high dose group withdrew from the study in the first year, due to oedema of the lower limbs.

No other relevant outcomes were reported.

Oral versus vaginal administration of oestradiol and dydrogesterone

One study included 20 women who were diagnosed with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) and awaiting oocyte donation (Feng 2021). See Table 3.

Primary outcome

Uterine volume (mL) measured after 14 days of treatment

There were insufficient data for statistical analyses. Trial authors reported no difference in the change of uterine volume between the oral and vaginal administration groups after 14 days.

Uterine volume (mL) measured after 21 days of treatment

There were insufficient data for statistical analyses. Trial authors reported no difference in the change of uterine volume between the oral and vaginal administration groups after 21 days.

Data were insufficient for subgroup or sensitivity analyses.

Secondary outcomes

Endometrial thickness (mm) measured after 14 days of treatment

There were insufficient data for statistical analyses. Trial authors reported a higher increase in endometrial thickness in the vaginal administration compared to oral administration groups after 14 days.

Endometrial thickness (mm) measured after 21 days of treatment

There were insufficient data for statistical analyses. Trial authors reported a higher increase in endometrial thickness in the vaginal administration compared to oral administration groups after 21 days.

No other relevant outcomes (including adverse events) were reported.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The current evidence was limited by volume, as we only identified three studies investigating different populations that were eligible for this review. The number of included participants ranged from 12 to 20, which means the studies were underpowered to answer their respective population, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) questions.

Nabhan 2009 randomised 12 girls diagnosed with Turner syndrome and naive to oestrogen, to receive either conjugated oral oestrogen or transdermal oestradiol for one year. We are uncertain of the effect of conjugated oral oestrogens compared to transdermal oestradiol on the uterine volume after 12 months of treatment, due to very low‐certainty evidence.

Cleemann 2020 randomised 20 women diagnosed with Turner syndrome based on karyotyping, who had completed pubertal induction, to receive either a lower or a higher dose of 17ß‐oestradiol for five years. We are uncertain of the effect of a lower dose of 17ß‐oestradiol compared to a higher dose of 17ß‐oestradiol on the uterine volume, or adverse events after three or five years of treatment, due to very low‐certainty evidence.

Feng 2021 randomised 20 women diagnosed with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), and awaiting oocyte donation, to receive oestradiol and dydrogesterone, administered orally or vaginally. We are uncertain of the effect of the route of administration on uterine volume and endometrial thickness after 14 or 21 days of administration, due to very low‐certainty evidence.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Overall, there is paucity of evidence about the effectiveness of the different regimens of hormone therapy (HT) used. The regimen to maximise the reproductive potential for young and older age groups remain unclear. In the absence of clearly reported adverse events (or their absence), the long‐term safety profiles of these hormone therapies remain unclear. We only included studies reporting on adverse events in the context of HT administered for reproductive reasons in women with POI, while HT administered for bone or cardiovascular health may have a clearer safety profile.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the included studies were at low or unclear risk of bias due to lack of details for randomisation or allocation concealment, according to the criteria specified by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). Using GRADE methodology, the certainty of evidence for all the outcomes was very low, mainly due to the very serious imprecision, secondary to the small sample size.

Potential biases in the review process

We tried to minimise potential biases in the review process by conducting a systematic search of multiple databases; however, we might have missed eligible studies that were published in other languages, not captured by our search strategy. Two review authors independently selected studies for inclusion, extracted and analysed data, and assessed risk of bias, which increases our confidence in the accuracy of the present review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Five reviews relevant to the topic of the present review have been published. They included observational, randomised, and non‐randomised trials that were not eligible for the present review.

The first systematic review of treatment strategies to achieve a pregnancy in women diagnosed with POI included 52 case reports, eight observational studies, nine uncontrolled studies, and seven controlled trials (Kasteren 1999). Treatment options comprised various combinations of clomiphene citrate, gonadotropins (HMG), various oestrogen regimens, combined oral contraceptive (COC), gonadotropin‐releasing hormone analogues (GnRH‐a), corticosteroids, and hypophysectomy, followed by hormonal treatment. Authors concluded that several types of interventions were equally ineffective, and they were unable to ascertain whether these interventions should be preferred to no therapy, due to a general lack of a control group in the included studies.

In a review of practices and published data for the management of women with POI with a focus on uterine development, authors concluded that a minimal daily dose of 2 mg of oral oestradiol valerate or its equivalent was needed to achieve an optimal uterine growth, while COC or an oestrogen plus progestogen preparation may be administered after puberty (Gelbaya 2011). They suggested there is a need for a large national or international database for women with POI to serve as a valuable source for research and cohort studies.

In a systematic review of 12 prospective trials investigating medical alternatives to oocyte donation in women with POI, trial authors reported no significant differences between the study groups (Robles 2013). Trials included no control groups, while interventions varied between conjugated oestrogens combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate and HMG, ethinylestradiol combined with medroxiprogesterone acetate and HMG, GnRHa combined with histrelin and HMG, leuprolide acetate combined with HMG, micronized oestradiol combined with medroxyprogesterone, ethinylestradiol and levonorgestrel, prednisolone, buserelin acetate combined with HMG, and dexamethasone combined with HMG.

In a review of the literature, trial authors acknowledged the paucity of data, and concluded that it is important to lower gonadotropin levels to the physiological range before embarking on any fertility treatment (Ben‐Naghi 2014). They recommend multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials to recruit women from a variety of national and international centres, to increase the sample size and therefore, achieve a powered study.

The most recent review of treatments to improve pregnancy rates in women diagnosed with POI included two randomised controlled trials, two observational studies, and 11 interventional studies (Fraison 2019). Trial authors acknowledged the paucity of data, and concluded that no treatment for infertility has so far shown superiority.

The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) guideline on the management of women with POI provides 99 recommendations, 24 out of which were formulated on hormone replacement therapy (ESHRE 2016). Guideline authors suggest that 17ß‐oestradiol is preferred to ethinylestradiol or conjugated equine oestrogens for oestrogen replacement, while oral cyclical combined treatment is preferred to micronized natural progesterone for endometrial protection. For puberty induction, guideline authors recommend skipping combined oral contraceptive, and instead use 17ß‐oestradiol, starting with a low dose at the age of 12 years, and gradual increasing over two to three years. They noted the inconclusive evidence to support the optimum mode of administration (oral or transdermal).

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) committee opinion on POI in adolescents and young women recommends transdermal, oral, or occasionally, transvaginal oestradiol in doses of 100 micrograms daily, as the therapy of choice to mimic a physiologic dose range, and to achieve symptomatic relief following completion of puberty (ACOG 2022). Oral contraceptives are not recommended as first‐line hormonal therapy, due to their higher doses of oestrogen.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

No clear conclusions can be drawn in this systematic review, due to the very low certainty of the evidence.

Implications for research.

Previous research in the field of hormone therapy (HT) for women with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) has mainly focused on the optimisation of bone and cardiovascular health. There is a need for pragmatic, well designed, randomised controlled trials, with adequate power to detect differences between various HT regimens on uterine growth; endometrial development; and pregnancy outcomes, following the transfer of donated gametes or embryos in women diagnosed with POI.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2010

Acknowledgements

We thank Helen Nagels (Managing Editor), Marian Showell (Information Specialist), and the editorial board of the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility (CGF) Group for their invaluable assistance in developing this review. We acknowledge the contributions of Cindy Farquhar and Luciano Nardo to early versions of this review.

We thank Professor Martha Hickey, Dr Elena Kostova, and Dr Susannah O'Sullivan for providing peer review comments.

We thank Victoria Pennick for copy editing the manuscript.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group (CGF) specialised register search strategy

ProCite platform

Searched from inception to 27 September 2021

Keywords CONTAINS "premature ovarian failure" or "ovarian failure" or "anovulation" or "amenorrhea" or "amenorrhoea " or Title CONTAINS "premature ovarian failure" or "ovarian failure" or "anovulation" or "amenorrhea" or "amenorrhoea "

AND

Keywords CONTAINS "HRT" or "HT" or "Hormone Therapy" or "Hormone Substitution" or "estrogen" or "progestagen" or "Progesterone" or "combined oral contraceptive" or "oral contraceptive" or "OCP" or "Oral Contraceptive Agent" or "oral contraceptive pill" or "oral contraceptives" or "oral conjugated estrogen" or "conjugated equine estrogen" or "conjugated equine estrogens" or "conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) "or "conjugated equine estrogens + progesterone" or "Conjugated Estrogen" or "conjugated estrogens" or "progestagen" or "Progesterone" or "progestin" or "progestogen" or "Norgestrel" or "norethisterone" or "desogestrel" or "gestodene" or "estrogen" or "oestrogen" or "oestrodiol" or "Estradiol" or Title CONTAINS "HRT" or "HT" or "Hormone Therapy" or "Hormone Substitution" or "estrogen" or "progestagen" or "Progesterone" or "combined oral contraceptive" or "oral contraceptive" or "OCP" or "Oral Contraceptive Agent" or "oral contraceptive pill" or "oral contraceptives" (323 records)

Appendix 2. CENTRAL via the CENTRAL register of studies (CRSO) search strategy

Web platform

Searched 27 September 2021

#1 MESH DESCRIPTOR Primary Ovarian Insufficiency EXPLODE ALL TREES 151

#2 (ovar* fail*):TI,AB,KY 312

#3 POF:TI,AB,KY or (ovar* insufficien*):TI,AB,KY 396

#4 MESH DESCRIPTOR Anovulation EXPLODE ALL TREES 147

#5 MESH DESCRIPTOR Menopause, Premature EXPLODE ALL TREES 65

#6 anovulation:TI,AB,KY 638

#7 (prematur* menopaus*):TI,AB,KY 50

#8 MESH DESCRIPTOR Amenorrhea EXPLODE ALL TREES 332

#9 (resistant ovar* syndrome*):TI,AB,KY 1

#10 (Amenorrhea or Amenorrhoea):TI,AB,KY 1863

#11 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 2970

#12 MESH DESCRIPTOR Hormone Replacement Therapy EXPLODE ALL TREES 2953

#13 (hormon* adj2 therap*):TI,AB,KY 13988

#14 (estrogen therap*):TI,AB,KY 1228

#15 (oestrogen therap*):TI,AB,KY 129

#16 (oestradiol or estradiol):TI,AB,KY 11206

#17 MESH DESCRIPTOR Contraceptives, Oral EXPLODE ALL TREES 4599

#18 (oral contraceptive*):TI,AB,KY 3376

#19 (contracept* pill*):TI,AB,KY 751

#20 (hormon* substitution):TI,AB,KY 1271

#21 progest*:TI,AB,KY 9529

#22 MESH DESCRIPTOR Estradiol EXPLODE ALL TREES 4543

#23 MESH DESCRIPTOR Estrogens, Conjugated (USP) EXPLODE ALL TREES 1003

#24 (conjugated equine oestrogen*):TI,AB,KY 76

#25 (conjugated equine estrogen*):TI,AB,KY 765

#26 CEE:TI,AB,KY 452

#27 OCP:TI,AB,KY 298

#28 #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 32415

#29 #11 AND #28 1255

Appendix 3. MEDLINE search strategy

Ovid platform

Searched from 1946 to 27 September 2021

1 exp Primary Ovarian Insufficiency/ (2936) 2 ovar$ fail$.tw. (4069) 3 POF.tw. (1735) 4 exp anovulation/ or exp menopause, premature/ (3322) 5 anovulation.tw. (2840) 6 prematur$ menopaus$.tw. (753) 7 exp Amenorrhea/ (9969) 8 gonadotropin$ resistant ovar$ syndrome$.tw. (15) 9 puberty failure.tw. (9) 10 (Amenorrhea or amenorrhoea).tw. (13846) 11 or/1‐10 (27847) 12 exp hormone replacement therapy/ or exp estrogen replacement therapy/ (25558) 13 (hormon$ adj2 therap$).tw. (41841) 14 estrogen therap$.tw. (3570) 15 oestrogen therap$.tw. (674) 16 (oestradiol or estradiol).tw. (96100) 17 exp contraceptives, oral/ or exp contraceptives, oral, combined/ or exp ethinyl estradiol‐norgestrel combination/ or exp contraceptives, oral, hormonal/ or exp contraceptives, oral, sequential/ or exp contraceptives, oral, synthetic/ (50675) 18 oral contraceptive$.tw. (24939) 19 contracept$ pill$.tw. (4084) 20 exp progesterone/ or exp algestone/ or exp 20‐alpha‐dihydroprogesterone/ or hydroxyprogesterones/ or exp 17‐alpha‐hydroxyprogesterone/ or exp medroxyprogesterone/ or exp medroxyprogesterone 17‐acetate/ (71400) 21 hormon$ substitution.tw. (719) 22 progest$.tw. (101426) 23 exp Estradiol/ (84984) 24 exp "Estrogens, Conjugated (USP)"/ (3645) 25 conjugated equine oestrogen$.tw. (148) 26 conjugated equine estrogen$.tw. (1250) 27 or/12‐26 (295095) 28 27 and 11 (7923) 29 randomized controlled trial.pt. (544485) 30 controlled clinical trial.pt. (94426) 31 randomized.ab. (534954) 32 placebo.tw. (227701) 33 clinical trials as topic.sh. (197496) 34 randomly.ab. (366462) 35 trial.ti. (248117) 36 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (90646) 37 or/29‐36 (1429134) 38 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (4890193) 39 37 not 38 (1313883) 40 28 and 39 (961)

Appendix 4. Embase search strategy

Ovid platform

Searched from 1980 to 27 September 2021

1 exp ovary insufficiency/ or exp anovulation/ or exp premature ovarian failure/ (16167) 2 (ovar$ insufficien$ or ovar$ failure).tw. (7967) 3 POF.tw. (2399) 4 anovulation.tw. (3652) 5 exp Early Menopause/ (2865) 6 prematur$ menopaus$.tw. (1220) 7 exp amenorrhea/ or exp primary amenorrhea/ or exp secondary amenorrhea/ (21659) 8 gonadotropin$ resistant ovar$ syndrome$.tw. (9) 9 puberty failure.tw. (8) 10 (Amenorrhea or amenorrhoea).tw. (16135) 11 or/1‐10 (45685) 12 exp hormonal therapy/ or exp hormone substitution/ or exp steroid therapy/ (286452) 13 hormone therap$.tw. (21168) 14 estrogen therap$.tw. (4277) 15 oestrogen therap$.tw. (709) 16 (oestradiol or estradiol).tw. (105469) 17 exp Oral Contraceptive Agent/ (57332) 18 oral contraceptive$.tw. (25881) 19 contracept$ pill$.tw. (5558) 20 exp Progesterone/ (82303) 21 hormon$ substitution.tw. (1120) 22 progest$.tw. (112297) 23 exp Estradiol/ (113798) 24 exp Conjugated Estrogen/ (9779) 25 conjugated equine estrogen$.tw. (1517) 26 Estradiol.tw. (93158) 27 or/12‐26 (536500) 28 27 and 11 (16403) 29 Clinical Trial/ (1005398) 30 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (673265) 31 exp randomization/ (92009) 32 Single Blind Procedure/ (43791) 33 Double Blind Procedure/ (185022) 34 Crossover Procedure/ (68065) 35 Placebo/ (357842) 36 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (266687) 37 Rct.tw. (43495) 38 random allocation.tw. (2213) 39 randomly allocated.tw. (39104) 40 allocated randomly.tw. (2687) 41 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (831) 42 Single blind$.tw. (27280) 43 Double blind$.tw. (216405) 44 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (1394) 45 placebo$.tw. (325794) 46 prospective study/ (713533) 47 or/29‐46 (2409007) 48 case study/ (80893) 49 case report.tw. (450455) 50 abstract report/ or letter/ (1164109) 51 or/48‐50 (1683181) 52 47 not 51 (2351087) 53 28 and 52 (3268)

Appendix 5. PsycINFO search strategy

Ovid platform

Searched from 1806 to 27 September 2021

1 exp Endocrine Sexual Disorders/ (1852) 2 ovar$ fail$.tw. (99) 3 POF.tw. (49) 4 anovulation.tw. (67) 5 prematur$ menopaus$.tw. (45) 6 exp Amenorrhea/ (267) 7 gonadotropin$ resistant ovar$ syndrome$.tw. (0) 8 puberty failure.tw. (0) 9 Amenorrhea.tw. (740) 10 or/1‐9 (2800) 11 exp Hormone Therapy/ (2184) 12 (hormone adj2 therap$).tw. (2243) 13 estrogen therap$.tw. (256) 14 oestrogen therap$.tw. (16) 15 (oestradiol or estradiol).tw. (6793) 16 exp Oral Contraceptives/ (990) 17 oral contraceptive$.tw. (1544) 18 contracept$ pill$.tw. (359) 19 hormon$ substitution.tw. (36) 20 progest$.tw. (5052) 21 exp Estradiol/ (3217) 22 conjugated equine oestrogen$.tw. (4) 23 conjugated equine estrogen$.tw. (83) 24 CEE.tw. (210) 25 or/11‐24 (14266) 26 10 and 25 (297) 27 random.tw. (62904) 28 control.tw. (472104) 29 double‐blind.tw. (23881) 30 clinical trials/ (11978) 31 placebo/ (6085) 32 exp Treatment/ (1110000) 33 or/27‐32 (1530231) 34 26 and 33 (197)

Appendix 6. CINAHL search strategy

EBSCO platform

Searched from 1960 to 4 June 2020 (all CINAHL records after this time are contained in the CRSO search, i.e. those from 4 June 2020 to 27 September 2021)

| # | Query | Results |

| S33 | S20 AND S32 | 81 |

| S32 | S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 | 1,602,363 |

| S31 | TX allocat* random* | 13,308 |

| S30 | (MH "Quantitative Studies") | 30,594 |

| S29 | (MH "Placebos") | 13,723 |

| S28 | TX placebo* | 71,439 |

| S27 | TX random* allocat* | 13,308 |

| S26 | (MH "Random Assignment") | 68,328 |

| S25 | TX randomi* control* trial* | 221,958 |

| S24 | TX ( (singl* n1 blind*) or (singl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (doubl* n1 blind*) or (doubl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (tripl* n1 blind*) or (tripl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (trebl* n1 blind*) or (trebl* n1 mask*) ) | 1,218,806 |

| S23 | TX clinic* n1 trial* | 295,324 |

| S22 | PT Clinical trial | 110,850 |

| S21 | (MH "Clinical Trials+") | 319,938 |

| S20 | S6 AND S19 | 370 |

| S19 | S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 | 57,314 |

| S18 | TX progest* | 12,119 |

| S17 | (MH "Progesterone+") | 5,740 |

| S16 | (MM "Estrogens, Conjugated") | 389 |

| S15 | (MM "Estradiol") OR (MH "Estrogens") | 10,886 |

| S14 | TX hormon* substitution | 44 |

| S13 | TX oral contraceptive* | 9,210 |

| S12 | (MM "Contraceptives, Oral") OR (MM "Contraceptives, Oral Combined") | 4,000 |

| S11 | TX (oestradiol or estradiol) | 7,790 |

| S10 | TX oestrogen therap* | 5,410 |

| S9 | TX estrogen therap* | 5,410 |

| S8 | TX (hormon* N2 therap*) | 31,591 |

| S7 | (MM "Hormone Replacement Therapy") OR (MM "Hormone Therapy") | 7,385 |

| S6 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 | 1,311 |

| S5 | TX prematur* menopaus* | 640 |

| S4 | (MM "Menopause, Premature") | 278 |

| S3 | TX POF | 197 |

| S2 | TX ovar* N3 fail* | 664 |

| S1 | TX Premature Ovarian Failure | 377 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Conjugated oral oestrogens versus transdermal 17ß‐estradiol.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Uterine volume (mL) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1.1 Measured at baseline | 1 | 12 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐1.88, 1.28] |

| 1.1.2 Measured after 12 months | 1 | 12 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐18.20 [‐23.18, ‐13.22] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Cleemann 2020.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Design: 2‐arm parallel RCT | |

| Participants | Number: 20 Women's age: 16 to 25 years Inclusion criteria: women with Turner syndrome diagnosed by previous karyotyping, who achieved final height, and finished growth hormone treatment, finished pubertal induction, and current treatment with an oral 17β‐estradiol dose of 2 mg Exclusion criteria: contraindications to the study medication, and current use of other medication with known or potential interactions with the study medication |

|

| Interventions | Intervention 1: lower dose group (LD group) took Trisekvens (2 mg 17ß‐estradiol/d for days 1 to 12, 2 mg 17ß‐estradiol/d and 1 mg norethisterone acetate/d for days 13 to 22, and 1 mg 17ß‐estradiol/d for days 23 to 28; Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) orally combined with placebo on days 1 through 22 of the menstrual cycle Intervention 2: higher dose group (HD group) took Trisekvens orally combined with estradiol 2 mg (Novo Nordisk) on days 1 through 22 of the menstrual cycle |

|

| Outcomes | uterine volume after 3 and 5 years of treatment | |

| Notes | trial registration: NCT00134745 Authors emailed 13 October 2021 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | study identified as RCT, but no details for randomisation provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | no allocation concealment details provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | no blinding details provided, but unlikely to influence the outcome |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | no blinding details provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 4 participants from the high dose group did not complete the study period |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | reported on relevant outcomes for the study question according to registry entry |

| Other bias | Low risk | no other sources of bias identified |

Feng 2021.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Design: 2‐arm parallel RCT | |

| Participants | Number: 20 Women's age: 20 to 35 years Inclusion criteria: women diagnosed with POI and awaiting oocyte donation. POI was diagnosed based on 4 to 6 months of amenorrhoea, follicle‐stimulating hormone concentrations > 40 mIU/mL at least twice at an internal of 4 to 6 weeks, oestradiol concentrations < 20 pg/mL, endometrium double‐wall thickness < 5 mm, normal uterine cavity, and no steroid replacement drug treatment in the previous three months. Exclusion criteria: metabolic disorders, a history of thromboembolism, a family history of thrombosis or cardiovascular disease, and a history of blood system disorders |

|

| Interventions | Intervention 1: women in the oral group received femoston 2/10 (Abbott Biologicals B.V, Weesp, Netherlands) sequentially by oral administration, which comprised 14 red pills containing 2 mg oestradiol, 14 yellow pills containing 2 mg oestradiol, and 10 mg dydrogesterone Intervention 2: women in the vaginal group received femoston 1/10 vaginally, which comprised 14 white pills containing 1 mg oestradiol, and 14 grey pills containing 1 mg oestradiol and 10 mg dydrogesterone. |

|

| Outcomes | endometrial thickness and uterine volume after 14 and 21 days of treatment | |

| Notes | trial registration: ChiCTR1900026410 authors emailed: 13 October 2021 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | study identified as RCT, but no details for randomisation provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | no allocation concealment details provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | no blinding details reported, but unlikely to affect outcomes |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | ultrasound examiners blinded to treatment groups |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | all participants accounted for |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | reported on relevant outcomes for the study question according to registry entry |

| Other bias | Low risk | no other sources of bias identified |

Nabhan 2009.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Design: 2‐arm parallel RCT | |

| Participants | Number: 12 Women's age: 11 to 17 years Inclusion criteria: girls aged 10 years and older who were naive to oestrogen, and on growth hormone therapy (0.375 mg/kg week) for at least 6 months. Girls with other conditions, such as hypothyroidism needed to be on full hormone replacement before enrolment. Exclusion criteria: girls with spontaneous pubertal development, any chronic illness that could affect absorption of oral medication, or on any medication (other than thyroxine) that could affect bone mineral density |

|

| Interventions | Intervention 1: conjugated oral oestrogen was administered at a dose of 0.3 mg every day for the first 6 months, followed by 0.3 mg alternating with 0.625 mg every day for the second 6 months Intervention 2: transdermal oestradiol group was treated with a 0.025 mg patch twice a week for 6 months, followed by a 0.0375 mg patch twice a week for the second 6 months |

|

| Outcomes | uterine volume after 12 months of treatment | |

| Notes | authors emailed 13 October 2021 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | randomisation was computer generated and stratified by bone age |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | no allocation concealment details provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | no blinding details reported, but unlikely to affect outcomes |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | no blinding details reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | all participants accounted for |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | reported on relevant outcomes for the study question |

| Other bias | Low risk | no other sources of bias identified |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Achiron 1995 | not RCT |

| Badawy 2007 | not the intervention of interest |

| Benetti‐Pinto 2020 | not the outcomes of interest |

| Ben‐Naghi 2014 | review |

| Burgos 2017 | review |

| Fraison 2019 | review |

| Gault 2011 | not the outcomes of interest |

| Gelbaya 2011 | review |

| Kasteren 1999 | review |

| Labarta 2012 | not the outcomes of interest |

| Li 1992 | cross‐over RCT |

| Liu 2019 | review |

| O'Donnell 2012 | cross‐over RCT |

| Robles 2013 | review |

| Ross 2011 | not the outcomes of interest |

| Snajderova 2003 | not RCT |

| Sullivan 2016 | review |

| Tartagni 2007 | not the outcomes of interest |

| Webber 2017 | review |

Differences between protocol and review

The term 'premature ovarian failure' was replaced by 'premature ovarian insufficiency' in the title and throughout the review.

Contributions of authors

Laurentiu Craciunas: principal review author, literature search, study selection, data extraction and interpretation, drafting of review

Nikolaos Zdoukopoulos: literature search, study selection, data extraction, manuscript formatting, contribution to the final version of the review

Suganthi Vinayagam: literature search, contribution to the final version of the review

Lamiya Mohiyiddeen: senior review author, consultation in case of disagreements, contribution to the final version of the review

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

None, Other

Not applicable

External sources

-

None, Other

Not applicable

Declarations of interest

LC, NZ, SV, and LM have no interests to declare.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Cleemann 2020 {published data only}

- Cleemann L, Holm K, Fallentin E, Møller N, Kristensen B, Skouby SO, et al. Effect of dosage of 17ß-Estradiol on uterine growth in Turner syndrome—a randomized controlled clinical pilot trial. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2020;105(3):e716-24. [DOI: 10.1210/clinem/dgz061] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Feng 2021 {published data only}

- Feng W, Nie L, Wang X, Yang F, Pan P, Deng X. Effect of oral versus vaginal administration of estradiol and dydrogesterone on the proliferative and secretory transformation of endometrium in patients with premature ovarian failure and preparing for assisted reproductive technology. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 2021;15:1521-9. [DOI: 10.2147/DDDT.S297236] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nabhan 2009 {published data only}

- Nabhan ZM, Dimeglio LA, Qi R, Perkins SM, Eugster EA. Conjugated oral versus transdermal estrogen replacement in girls with Turner syndrome: a pilot comparative study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2009;94:2009-14. [DOI: 10.1210/jc.2008-2123] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Achiron 1995 {published data only}

- Achiron R, Levran D, Sivan E, Lipitz S, Dor J, Mashiach S. Endometrial blood flow response to hormone replacement therapy in women with premature ovarian failure: a transvaginal Doppler study. Fertility and Sterility 1995;63:550-4. [DOI: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57424-x] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Badawy 2007 {published data only}

- Badawy A, Goda H, Ragab A. Induction of ovulation in idiopathic premature ovarian failure: a randomized double-blind trial. Reproductive Biomedicine Online 2007;15:215-9. [DOI: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60711-0] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Benetti‐Pinto 2020 {published data only}

- Benetti-Pinto CL, Giraldo HP, Giraldo AE, Mira TA, Yela DA. Interferential current: a new option for the treatment of sexual complaints in women with premature ovarian insufficiency using systemic hormone therapy: a randomized clinical trial. Menopause 2020;27:519-25. [DOI: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001501] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ben‐Naghi 2014 {published data only}

- Ben-Nagi J, Panay N. Premature ovarian insufficiency: how to improve reproductive outcome? Climacteric 2014;17:242-6. [DOI: 10.3109/13697137.2013.860115] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burgos 2017 {published data only}

- Burgos N, Cintron D, Latortue-Albino P, Serrano V, Rodriguez Gutierrez R, Faubion S, et al. Estrogen-based hormone therapy in women with primary ovarian insufficiency: a systematic review. Endocrine 2017;58:13-425. [DOI: 10.1007/s12020-017-1435-x] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fraison 2019 {published data only}

- Fraison E, Crawford G, Casper G, Harris V, Ledger W. Pregnancy following diagnosis of premature ovarian insufficiency: a systematic review. Reproductive Biomedicine Online 2019;39:467-76. [DOI: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.04.019] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gault 2011 {published data only}

- Gault EJ, Perry RJ, Cole TJ, Casey S, Paterson WF, Hindmarsh PC, et al, British Society for Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes. Effect of oxandrolone and timing of pubertal induction on final height in Turner's syndrome: randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2011;342:d1980. [DOI: 10.1136/bmj.d1980] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gelbaya 2011 {published data only}

- Gelbaya T, Vitthala S, Nardo L, Seif M. Optimizing hormone therapy for future reproductive performance in women with premature ovarian failure. Gynecological Endocrinology 2011;27:1-7. [DOI: 10.3109/09513590.2010.501875] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kasteren 1999 {published data only}

- Kasteren YM, Schoemaker J. Premature ovarian failure: a systematic review on therapeutic interventions to restore ovarian function and achieve pregnancy. Human Reproduction Update 1999;5:483-92. [DOI: 10.1093/humupd/5.5.483] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Labarta 2012 {published data only}

- Labarta JI, Moreno ML, López-Siguero JP, Luzuriaga C, Rica I, Sánchez-del Pozo J, et al, Spanish Turner Working Group. Individualised vs fixed dose of oral 17β-oestradiol for induction of puberty in girls with Turner syndrome: an open-randomised parallel trial. European Journal of Endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies 2012;167:523-9. [DOI: 10.1530/EJE-12-0444] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Li 1992 {published data only}

- Li TC, Cooke ID, Warren MA, Goolamallee M, Graham RA, Aplin JD. Endometrial responses in artificial cycles: a prospective study comparing four different oestrogen dosages. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1992;99:751-6. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13878.x] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Liu 2019 {published data only}

- Liu W, Nguyen TN, Tran Thi TV, Zhou S. Kuntai capsule plus hormone therapy vs. hormone therapy alone in patients with premature ovarian failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine : ECAM 2019;2019:2085804. [DOI: 10.1155/2019/2085804] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Donnell 2012 {published data only}