Abstract

The goal of this study was to identify a candidate commercial cell line for the replication of African swine fever virus (ASFV) by comparing several available cell lines with various medium factors. In the sensitivity test of cells, MA104 and MARC-145 had strong potential for ASFV replication. Next, MA104 cells were used to compare the adaptation of ASFV obtained from tissue homogenates and blood samples in various infectious media. At the 10th passage, the ASFV obtained from the blood sample had a significantly higher viral load than that obtained from the tissue sample (P = 0.000), exhibiting a mean cycle threshold (Ct) value = 20.39 ± 1.99 compared with 25.36 ± 2.11. For blood samples, ASFV grew on infectious medium B more robustly than on infectious medium A (P = 0.006), corresponding to a Ct value = 19.58 ± 2.10 versus 21.20 ± 1.47. African swine fever virus originating from blood specimens continued to multiply gradually and peaked in the 15th passage, exhibiting a Ct value = 14.36 ± 0.22 in infectious medium B and a Ct value = 15.42 ± 0.14 in infectious medium A. When ASFV was cultured from tissue homogenates, however, there was no difference (P = 0.062) in ASFV growth between infectious media A and B. A model was developed to enhance ASFV replication through adaptation to MA104 cells. The lack of mutation at the genetic segments encoding p72, p54, p30, and the central hypervariable region (CVR) in serial culture passages is important in increasing the probability of maintaining immunogenicity when developing a vaccine candidate.

Résumé

L’objectif de cette étude était d’identifier une lignée cellulaire commerciale candidate pour la réplication du virus de la peste porcine africaine (ASFV) en comparant plusieurs lignées cellulaires disponibles et différents milieux. Lors du test de sensibilité des cellules, MA104 et MARC-145 présentaient un fort potentiel pour la réplication d’AFSV. Par la suite, les cellules MA104 ont été utilisées pour comparer l’adaptation d’ASFV obtenu d’homogénats de tissus et d’échantillons de sang dans différents milieux. Au dixième passage, l’ASFV obtenu de l’échantillon de sang avait une charge virale significativement plus élevée que celle obtenue de l’échantillon de tissu (P = 0,000), avec une valeur seuil moyenne de cycles (Ct) de 20,39 ± 1,99 comparativement à 25,36 ± 2,11. Pour les échantillons sanguins, l’ASFV a poussé sur le milieu B de manière plus robuste que sur le milieu A (P = 0,006), ce qui correspond à une valeur Ct de 19,58 ± 2,10 versus 21,20 ± 1,47. L’ASFV provenant des échantillons sanguins continua de se multiplier graduellement et atteignit un pic au 15e passage, avec une valeur Ct de 14,36 ± 0,22 dans le milieu B et une valeur Ct de 15,42 ± 0,14 dans le milieu A. Toutefois, lorsque l’ASFV fut cultivé à partir des homogénats de tissus, il n’y avait pas de différence (P = 0,062) dans la croissance d’ASFV entre les milieux A et B. Un modèle a été développé pour augmenter la réplication d’ASFV par adaptation aux cellules MA104. L’absence de mutation au segment génétique codant pour p72, p54, p30, et la région hypervariable centrale (CVR) dans des passages en série en culture est importante en augmentant la probabilité de maintenir une immunogénicité lors du développement d’un vaccin candidat.

(Traduit par Docteur Serge Messier)

Introduction

African swine fever virus (ASFV) is an enveloped icosahedral double-stranded DNA virus that belongs to the genus Asfivirus and family Asfaviridae (1). African swine fever virus causes a highly contagious hemorrhagic disease with high mortality rates in domestic pigs. The virus has been isolated across various cell lines, but it has been challenging to identify a cell line in order to develop an effective commercial vaccine. Although many continuous cell lines, including Vero cells, are used for the propagation and titration of ASFV (2), the virus replicates most freely in a monocyte/macrophage lineage (3,4).

Among the various types of macrophages assessed, it has been suggested that pulmonary alveolar macrophages (PAMs) are more susceptible to ASFV infection than bone marrow-derived macrophages or blood monocytes (5,6). The maturation stage of PAMs, which is relevant to the expression of surface molecules, may contribute to virus entry into the cell (7). Despite the numerous advantages of PAMs, ethical constraints exist regarding these cells, as large quantities must be harvested in order to conduct a study. In addition, it is difficult to obtain consistent phenotypes of macrophages among different animals. It was recently determined that a commercial cell type (MA104) is highly stable when used to isolate ASFV from clinical samples (8).

In early 2019, ASFV invaded the pig population in northern Vietnam and was identified as genotype II, which was identical to the strain from China (9). According to the history of this disease, pigs in Vietnam suffered the fastest spread of this virus. After only 9 mo, 63/63 provinces announced the presence of the virus in pig herds, which caused heavy damage, threatening the stability of the pig herd in particular and the pork food production sector in general (10).

Research on the development of vaccines based on the prototype field virus is therefore urgently required, but identifying a commercial cell line that is suitable for high-yield viral replication is a major obstacle to effective vaccine development. The goal of this study was to identify a candidate commercial cell line by comparing the levels of ASFV replication in several available cell lines with various medium factors.

Materials and methods

Field sample and virus

Permission to collect the samples and conduct the lab analysis and study was obtained from the Center for Veterinary Diagnostics, Regional Animal Health Office No. 6, Ho Chi Minh City, Department of Animal Health, Vietnam, under the acceptance and approval of the Department of Animal Health (DAH), Vietnam and the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET), Vietnam: 2867-QĐ BGDDT, dated 01/10/2020.

The blood and visceral tissues of infected sows were collected from a farrow-to-finish, open-house family sow farm in southern Vietnam. The pathology in infected pigs was characteristic of the acute form of ASFV, which was in keeping with the findings of previous reports (11). Sows displayed anorexia, redness of skin, and high fever, followed by sudden death, and growing pigs also showed clinical signs, including recumbency with a high fever (over 41°C) and dominant redness of skin, followed by rapid death.

The blood and fresh organ specimens were confirmed to be ASFV-positive by routine polymerase chain reaction (PCR), as recommended by the Office International des Epizooties (OIE, Paris, France). The DNA of the infected ASFV strain was amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses and the partial genetic segments encoding p72, p54, p30, and the central hypervariable region (CVR) were sequenced using reference primers from previous studies (12–14) showing that the virus belonged to genotype II, which was entirely homologous to the first identified strain invading the Vietnamese pig population (9).

In addition, the ASFV sequences were submitted to GenBank, National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). They were named D/ASF/POT(TISSUE)/Vietnam/2019 and D/ASF/POB(BLOOD)/Vietnam/2019 originating from fresh specimens and D/ASF/P1/Vietnam/2019, D/ASF/P5/Vietnam/2019, D/ASF/P10/Vietnam/2019, and D/ASF/P15/Vietnam/2019 from cultured viruses at passages 1, 5, 10, and 15, which had accession numbers of MW451088–93 for genetic sequences encoding p72, MW451094–99 for genetic sequences encoding p54, MW451106–11 for genetic sequences encoding p30, and MW451100–05 for genetic sequences encoding CVR.

Cells

Cells were grown in Minimum Essential Eagle Medium-alpha modification (α-MEM), supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U of penicillin/mL, and 100 μg of streptomycin/mL. The cells were cultured in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. All cells (MA104, MARC-145, Vero, PK-15, PAM, and BHK21) were provided by ChoongAng Vaccine Laboratories (CAVAC), Daejeon, Republic of Korea.

ASFV isolation and optimized protocol

The samples of infected pigs were determined ASFV-positive by real-time (RT)-PCR and maintained in the laboratory. Tissue specimens, including spleen and lymph nodes, were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 100 U of penicillin/mL and 100 μg of streptomycin/mL, frozen and thawed 3 times, and then clarified by centrifugation at 12 000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were collected, filtered through a 0.22-μm filter, and used for cell inoculation.

The blood sample was also collected and anticoagulated using ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) from infected pigs, then used for isolation. In the first phase, an in-vitro experiment was conducted to detect ASFV-sensitive cell lines. Blood anticoagulated using EDTA from infected pigs had a cycle threshold (Ct) value = 20.21 (real-time PCR) and was used for isolation. The following cell lines were used for the test: PAM, MARC-145, Vero, PK-15, MA104, and BHK21. A mixing ratio of 50:50 diluted sample liquid and cells (1 × 106 cell/mL) was used and cells were incubated for 3 d in 5% CO2 at 37°C. The suspension was then inoculated in 10 mL of the growth medium in a 25-mL flask.

Infectious media (A and B) and α-MEM were used with individual cell lines to compare the adaptability of ASFV. Daily cell observation and viral load were identified by RT-PCR from 150 μL of the cultured supernatant and infected cells, and cells were subsequently stained to confirm the positivity of ASFV by immunocytochemistry (ICC) on day 7 after infection and incubation (passage 1). Next, the virus in the cultured fluid was sub-passaged continuously 2 times (passages 2 and 3) in a similar manner.

After that step, MA104 cells were used to evaluate the progressive adaptation of ASFV. The infectious media, A (VP-SFM AGT Medium; Gibco, ThermoFisher) and B (BMPro-V Medium; Daehan New Pharm, Hwaseong, Gyeonggi, Korea) and 2 sample types (blood and tissue homogenate) from the same diseased sow were used to determine whether ASFV had different responses to the medium composition from different sample sources on MA104. A 50:50 diluted sample liquid and cells (1 × 106 cell/mL) were mixed and incubated with 5% CO2 at 37°C for 3 d, as described previously. Next, the suspension was inoculated in 10 mL of the medium in a 25-mL flask. Daily cell observation and virus identification by RT-PCR from 150 μL of culture supernatant, as well as staining through ICC, confirmed the positivity of ASFV at 1, 3, 5, and 7 d. Next, the virus in the cultured fluid was continuously passaged a further 14 times (passages 2 to 15) in a similar manner.

Real-time PCR

Viral DNA in the cell culture supernatant was conducted to evaluate virus production in the cells. Real-time polymerase chain reaction targeting p72 genes was carried out on the infected culture supernatant of the cell line. The forward and reverse primers and probe were 5′-CTGCTCATGGTATCAATCTTATCGA-3′ and 5′-GATACCACAAGATC(AG)GCCGT-3′ and 5′-(FAM)-CC ACGGGAGGAATACCAACCCAGTG-3′-(TAMRA), respectively [(15); OIE recommendation]. The results are presented as Ct values.

Immunocytochemistry staining of cells in culture

Together with the RT-PCR, cells were specifically stained by immunocytochemistry (ICC), as previously described, with only slight modifications (16), to determine the viral protein expressed by ASFV infection. At 7 d post-infection (dpi) and under incubation at 37°C, the infected cells previously described were fixed and permeabilized in 80% acetone for 30 min at −20°C. After fixation, ICC was conducted using commercially available monoclonal antibodies specific for the viral protein p30 (Humimmu, Salem, New Hampshire, USA) to detect early protein synthesis.

Sequencing and genetic analysis in serial passages

DNA was extracted from blood and tissue homogenate before inoculation into cell culture (P0). Following passages 1 (P1), 5 (P5), 10 (P10), and 15 (P15), viral DNA from culture media was also obtained and subjected to comparative analysis of nucleotide and amino acid sequences through examination of amplified PCR products using reference primers from previous studies (12–14). In this analysis, sequences encoding the major structural viral proteins, such as p30, p54, p72, and CVR, were amplified, sequenced, and analyzed using Mega X software. Bootstrap values were calculated based on 1000 replicates by the neighbor-joining method. The immunogenic proteins p30, p54, and the aa-tetramer sequence within CVR were also further analyzed to determine whether there were any changes in the antigenic regions of ASFV among different culture passages and references (17,18).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data (Ct value of ASFV RT-PCR) were analyzed using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests at each time point.

Results

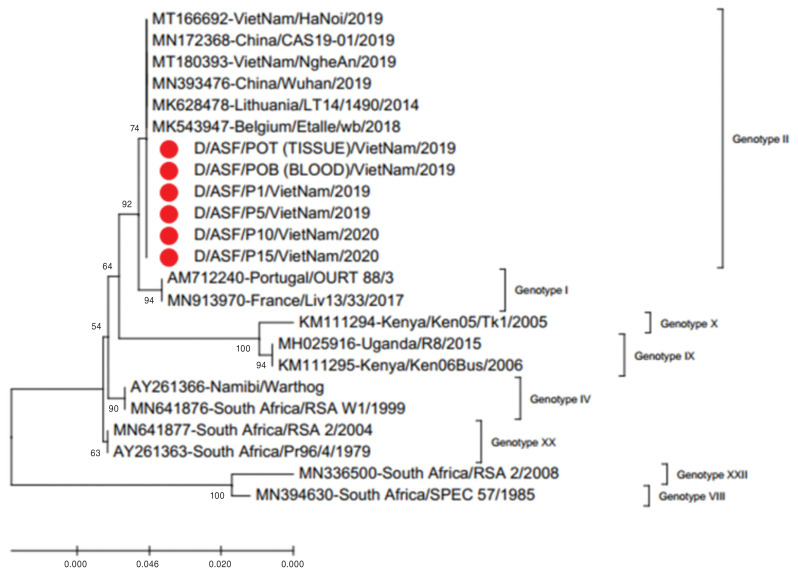

The ASFV used in this study belonged to genotype II (Figure 1) and the nucleotide sequences encoding p72, p54, p30, and CVR were similar to those of the first ASFV strain previously published in northern Vietnam (Vietnam/Hanoi/2019), which was identified as originating in China.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of 3 nucleotide sequences encoded p30, p54, and p72 of African swine fever virus (ASFV) used for isolation. The red circles represent the ASFV sequences from tissue homogenates and blood prior culture (D/ASF/POT(TISSUE)/Vietnam/2019, D/ASF/POB(BLOOD)/Vietnam/2019) and from cultured viruses at passage 1 (D/ASF/P1/Vietnam/2019), 5 (D/ASF/P5/Vietnam/2019), 10 (D/ASF/P10/Vietnam/2019), and 15 (D/ASF/P15/Vietnam/2019).

The inoculation of ASFV into the PAM, MARC-145, Vero, PK-15, MA104, and BHK21 cell lines, as monitored through 3 passages, showed that MA104 and MARC-145 have potential for ASFV replication (Table I). With infectious medium B, in MA104 cells, the Ct value of ASFV DNA was 23.55, 22.14, and 19.95 at passages 1, 2, and 3, respectively, whereas in MARC-145 cells, the Ct value of ASFV DNA was 25.51, 26.31, and 25.37 at passages 1, 2, and 3, respectively. With infectious medium A, in MA104 cells, the Ct value of ASFV DNA was 23.87, 23.06, and 19.24 at passages 1, 2, and 3, respectively, whereas in MARC-145 cells, the Ct value of ASFV DNA was 23.81, 24.71, and 22.84 at passages 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The findings therefore showed that infectious media A and B are more suitable and optimal than α-MEM for the growth and adaptation of ASFV in this study (Table I).

Table I.

The susceptibility of available cell lines to African swine fever virus in various passages (pass#).

| Media/passage | PAM | MARC-145 | Vero | PK-15 | MA104 | BHK21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious medium B | ||||||

| Pass#1 | NA | 25.51 | NA | NA | 23.55 | NA |

| Pass#2 | NA | 26.31 | NA | NA | 22.14 | NA |

| Pass#3 | NA | 25.37 | NA | NA | 19.95 | NA |

| Mock | NA | Neg | NA | NA | Neg | NA |

| Infectious medium A | ||||||

| Pass#1 | 22.79 | 23.81 | 30.01 | 23.13 | 23.87 | 26.41 |

| Pass#2 | 29.19 | 24.71 | 34.43 | 29.34 | 23.06 | Neg |

| Pass#3 | Neg | 22.84 | Neg | 36.02 | 19.24 | Neg |

| Mock | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| α-MEM | ||||||

| Pass#1 | 26.75 | 30.08 | 33.12 | 25.02 | 28.18 | 30.42 |

| Pass#2 | 27.53 | 32.91 | 35.01 | 29.34 | 30.75 | Neg |

| Pass#3 | Neg | 36.23 | Neg | 33.48 | Neg | Neg |

| Mock | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

NA — Not available.

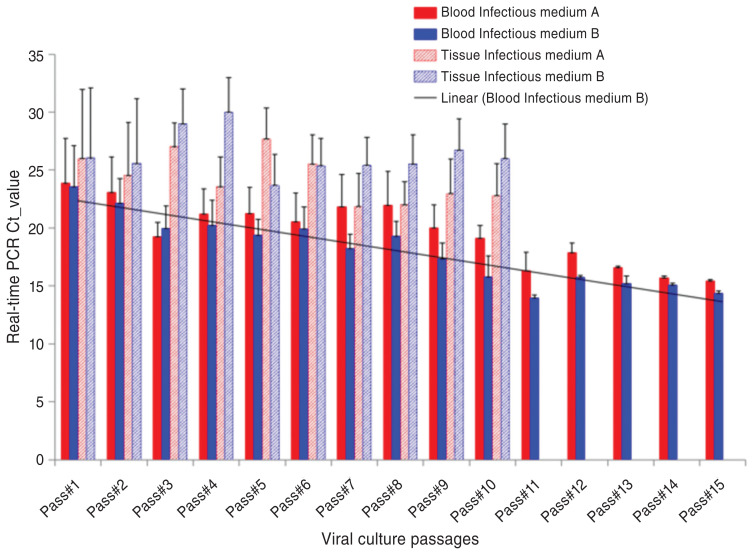

MA104 cells were used to compare ASFV growth and adaptation from tissue homogenate and blood samples on various infectious media (Figure 2). At the 10th passage, the ASFV obtained from the blood sample had a significantly higher viral load than that obtained from the tissue sample (P = 0.000), exhibiting a Ct value = 20.39 ± 1.99 compared with 25.36 ± 2.11. With the blood sample, ASFV grew on infectious medium B better than on infectious medium A (P = 0.006), corresponding to a Ct value = 19.58 ± 2.10 compared to 21.20 ± 1.47; ASFV originating from blood specimen continued to multiply gradually and peaked in the 15th passage with a Ct value = 14.36 ± 0.22 in infectious medium B and a Ct value = 15.42 ± 0.14 in infectious medium A.

Figure 2.

The dynamics of African swine fever virus (ASFV) load (Ct value RT-PCR) in MA104 cells over various culture passages (Pass#1 to Pass#15). The black curve represents the increase in viral load in several culture passages, presented by decreasing Ct value.

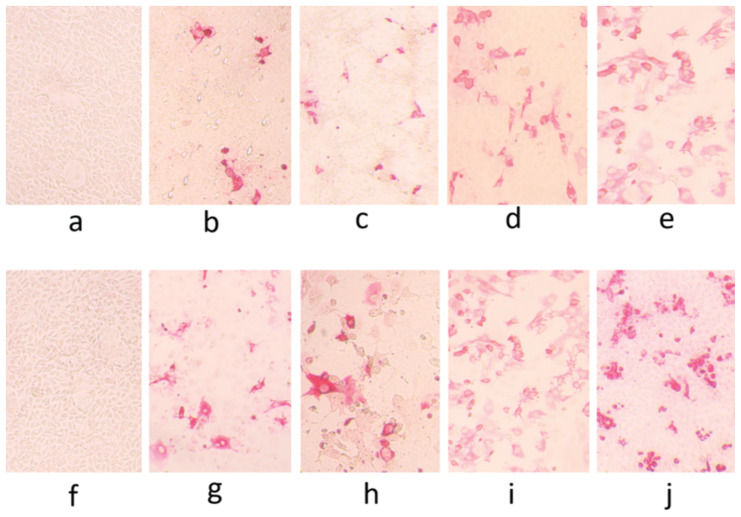

When cultured from tissue homogenate, however, there was no difference (P = 0.062) in ASFV growth between infectious media A and B. The results showed that in MA104 cells, ASFV isolation from blood sample under infectious medium B condition promoted optimal growth of this virus (black line in Figure 2; Figure 3). The sequences of nucleotide/amino acid encoding the p72, p54, p30, and CVR of the ASFV collected from MA104 cell supernatants through passages P0, P1, P5, P10, and P15 were 100% homologous when aligned. The antigenic regions in proteins p30 and p54 were highly conserved among the various ASFV culture passages (Table II). Moreover, the length and the aa tetramer sequence within CVR were absolutely conserved among the various ASFV culture passages.

Figure 3.

MA104 cells infected and mock-infected with African swine fever virus (ASFV) on the infectious medium A (a — mock culture, b — passage 1, c — passage 5, d — passage 10, and e — passage 15) and on the infectious medium B (f — mock culture, g — passage 1, h — passage 5, i — passage 10, and j — passage 15). The presence of the virus was determined by using a monoclonal antibody that detects ASFV protein p30 visualized using an immunoperoxidase assay.

Table II.

Comparison of the p30 and p54 antigenic regions of the studied African swine fever virus (ASFV) strains with those of other reference strains.

| Virus strain | Genotype | p30 | p54 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| 61-DIVKSARIYAGQGYTEHQAQEEWNMILHVL-90 | 96-ESSASSENIH-105 | Grp1 (65–75) EDIQFINPYQD |

Grp2a (93–107) ATTASVGKPVTGRPA |

Grp2b (98–113) VGKPVTGRPATNRPAT |

Grp3 (118–127) TDNPVTDRLV |

||

| D/ASF/POT/Vietnam/2019 | II | .............................. | .......... | ............ | ............... | ................ | .......... |

| D/ASF/POB/Vietnam/2019 | II | .............................. | .......... | ............ | ............... | ................ | .......... |

| D/ASF/P1/Vietnam/2019 | II | .............................. | .......... | ............ | ............... | ................ | .......... |

| D/ASF/P5/Vietnam/2019 | II | .............................. | .......... | ............ | ............... | ................ | .......... |

| D/ASF/P10/Vietnam/2019 | II | .............................. | .......... | ............ | ............... | ................ | .......... |

| D/ASF/P15/Vietnam/2019 | II | .............................. | .......... | ............ | ............... | ................ | .......... |

| MK543947/Belgium/Etalle/wb/2018 | II | .............................. | .......... | ............ | ............... | ................ | .......... |

| MK628478/Lithuania/LT14/1490/2014 | II | .............................. | .......... | ............ | ............... | ................ | .......... |

| MT180393/Vietnam/NgheAn/2019 | II | .............................. | .......... | ............ | ............... | ................ | .......... |

| MT166692/Vietnam/Hanoi/2019 | II | .............................. | .......... | ............ | ............... | ................ | .......... |

| MN172368/China/CAS19-01/2019 | II | .............................. | .......... | ............ | ............... | ................ | .......... |

| AM712240/Portugal/OURT88/3 | I | ......H....................... | .......S.. | ............ | .....A......... | A............... | .......... |

| MH025916/Uganda/R8/2015 | I | ...RN...........Q............. | ..TS.TSLES | ............ | ...GN....I.D... | ....I.D....D..V. | MNS......I |

Discussion

Although previous studies of ASFV isolation used primary pulmonary alveolar macrophage (PAM) cells because of their high adaptation (1,2,4,6), this cell line can only be used in research and is not a candidate for growing large amounts of ASFV for vaccine production due to high costs and the issue of animal ethics with the large-scale collection of primary cells. Meanwhile, several other commercial cell lines exhibit no evidence of stable replication of the ASFV.

A recent study by Rai et al (8) determined that a commercial cell line (MA104) is highly stable when used for isolating clinical samples. Our results in this study appear to be in keeping with the findings of that study. The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted some final steps necessary to obtain sufficient scientific information to enable publication. It should be noted, however, that the results obtained in our study and this previous work (8) demonstrate that MA104 is not only a stable cell line for isolating ASFV obtained from clinical samples, but also exhibits potential as a candidate cell line for commercial vaccine development.

A notable finding of this study was that in the same MA104 cells, ASFV from various sample sources (blood and tissue homogenate) exhibited significant differences in adaptability and replication. African swine fever virus (ASFV) has a restricted cellular tropism and the major target cells for replication are macrophages and monocytes and dendritic cells (1,3). The growth pattern of ASFV is therefore different in each tissue of pigs.

The ASFV isolation rate may vary depending on sample conditions and the amount of virus at the beginning of passage is important for viral adaptation. Modification of the medium composition in the maintenance and growth medium for the same MA104 cells also affected viral growth over 15 passages. The viral load was calculated via the Ct value of RT-PCR and the ICC staining technique used a p30 polyclonal antibody. Therefore, medium components may play an essential role in enhancing the reproduction of the ASFV in viral culture.

The results of this study showed that there was gradual adaptation and higher growth of ASFV in the serial subpassages, particularly from the 10th to 15th passages. Interestingly, ASFV isolated from blood on MA104 cells exhibited considerably better adaptation up to the 10th passage. In contrast, ASFV isolated from tissue samples exhibited slow adaptation and was terminated after the 10th passage.

Other cell lines, such as PAM, MARC-145, Vero, and PK-15, have been described in previous studies on the adaptive capacity of ASFV (5–7). In a recent study, several established porcine cell lines were compared to PAM in terms of ASFV infection and production, although the cells expressed low levels of specific receptors linked to the monocyte/macrophage lineage with low levels of viral infection (19). Interestingly, according to the results of this study, MA104 cells exhibited the most robust ASFV replication, which was also in keeping with the findings of Rai et al (8).

Further research to determine the best biological properties, multiplicity of infection (MOI), variability, and optimal medium composition for replicating ASFV in MA104 cells may therefore facilitate the development of an effective African swine fever vaccine. This study developed a model to optimize the adaptation of ASFV to MA104 cells. The virus showed high growth potential, but no mutations occurred in structural proteins (p30, p54, and p72) and the central hypervariable region (CVR). This lack of change is important in increasing the probability of maintaining immunogenicity when developing a vaccine candidate. This result is therefore the initial basis for carrying out further sequencing of the whole genome of cultured virus over passages, which plays an important role in concluding the conservation of this virus gene on cells that are candidates for vaccine development.

MA104 cells derived from kidney tissue of the African green monkey show specific sensitivity to the ASF virus. However, as the growth of ASFV on MA104 does not develop a clear cytopathic effect, it is difficult to titrate the virus in a conventional plaque formation assay rather than requiring the use of hemadsorption (HA) or special staining. The evidence of propagation of ASFV in the cells in this study was determined by 2 methods: RT-PCR (viral load exhibits according to the Ct value) and immunocytochemistry (ICC), and highly homologous results were obtained. Hemadsorption is often the criterion for determining the presence of ASFV in assays, but the high quality of blood required for testing is not always available in every laboratory. Moreover, some strains of virulent ASFV may not possess erythrocytic adsorption properties (20–22) and the application of immunocytochemistry in MA104 cells with clear backgrounds is more effective than using this technique in primary macrophage cells with peroxidase activity (8).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture and Forestry (IPET) through the Animal Disease Management Technology Development Program, funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA, Grant no. 11908105).

HIK, DTD, JYL, and TTN designed this study. HVV, QTVL, and TMT collected the samples. HIK, DTD, SCL, MHK, DTTN, TMT, QTVL, and TTNN conducted the viral isolation and molecular laboratory works. DDT, TTNN, and NMN conducted genetic analyses. JYL, SCL, TNT, and MHK provided technical assistance. DTD and HIK wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and JYL and TTN revised it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM, Laddomada A, Arias ML. African swine fever virus. In: Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, Zhang J, editors. Diseases of Swine. 11th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2019. pp. 443–456. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krug PW, Holinka LG, O’Donnell V, et al. The progressive adaptation of a Georgian isolate of African swine fever virus to vero cells leads to a gradual attenuation of virulence in swine corresponding to major modifications of the viral genome. J Virol. 2015;89:2324–2332. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03250-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCullough KC, Basta S, Knötig S, et al. Intermediate stages in monocyte-macrophage differentiation modulate phenotype and susceptibility to virus infection. Immunology. 1999;98:203–212. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Leon P, Bustos MJ, Carrascosa AL. Laboratory methods to study African swine fever virus. Virus Res. 2013;173:168–179. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodríguez F, Fernández A, Martín de las Mulas JP, Sierra MA, Jover A. African swine fever: Morphopathology of a viral haemorrhagic disease. Vet Rec. 1996;139:249–254. doi: 10.1136/vr.139.11.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blome S, Gabriel C, Beer M. Pathogenesis of African swine fever in domestic pigs and European wild boar. Virus Res. 2013;173:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez-Torres C, Gomez-Puertas P, Gomez-del-Moral M, et al. Expression of porcine CD163 on monocytes/macrophages correlates with permissiveness to African swine fever infection. Arch Virol. 2003;148:2307–2323. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rai A, Pruitt S, Ramirez-Medina E, et al. Identification of a continuously stable and commercially available cell line for the identification of infectious African swine fever virus in clinical samples. Viruses. 2020;12:820. doi: 10.3390/v12080820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le VP, Jeong DG, Yoon SW, et al. Outbreak of African swine fever, Vietnam, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:1433–1435. doi: 10.3201/eid2507.190303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woonwong Y, Do Tien D, Thanawongnuwech R. The future of the pig industry after the introduction of African swine fever into Asia. Anim Front. 2020;10:30–37. doi: 10.1093/af/vfaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nga BTT, Tran Anh Dao B, Nguyen Thi L, et al. Clinical and pathological study of the first outbreak cases of African swine fever in Vietnam, 2019. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:392. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bastos AD, Penrith ML, Crucière C, et al. Genotyping field strains of African swine fever virus by partial p72 gene characterisation. Arch Virol. 2003;148:693–706. doi: 10.1007/s00705-002-0946-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowlands RJ, Michaud V, Heath L, et al. African swine fever virus isolate, Georgia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1870–1874. doi: 10.3201/eid1412.080591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallardo C, Mwaengo DM, Macharia JM, et al. Enhanced discrimination of African swine fever virus isolates through nucleotide sequencing of the p54, p72, and pB602L (CVR) genes. Virus Genes. 2009;38:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s11262-008-0293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King DP, Reid SM, Hutchings GH, et al. Development of a TaqMan PCR assay with internal amplification control for the detection of African swine fever virus. J Virol Methods. 2003;107:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(02)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oura CA, Powell PP, Parkhouse RM. Detection of African swine fever virus in infected pig tissues by immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridisation. J Virol Methods. 1998;72:205–217. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu P, Lowe AD, Rodriguez YY, et al. Antigenic regions of African swine fever virus phosphoprotein P30. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2020;67:1942–1953. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrovan V, Murgia MV, Wu P, Lowe AD, Jia W, Rowland RRR. Epitope mapping of African swine fever virus (ASFV) structural protein, p54. Virus Res. 2020;279:197871. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.197871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sánchez EG, Riera E, Nogal M, et al. Phenotyping and susceptibility of established porcine cells lines to African Swine Fever Virus infection and viral production. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10369. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09948-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez JM, Yanez RJ, Almazan F, Vinuela E, Rodriguez JF. African swine fever virus encodes a CD2 homolog responsible for the adhesion of erythrocytes to infected cells. J Virol. 1993;67:5312–5320. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5312-5320.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zsak L, Borca MV, Risatti GR, et al. Preclinical diagnosis of African swine fever in contact-exposed swine by a real-time PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:112–119. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.112-119.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borca MV, O’Donnell V, Holinka LG, et al. Deletion of CD2-like gene from the genome of African swine fever virus strain Georgia does not attenuate virulence in swine. Sci Rep. 2020;10:494. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57455-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]