Abstract

Background

The ability to capture people’s movement throughout their home is a powerful approach to inform spatiotemporal patterns of routines associated with cognitive impairment. The study estimated indoor room activities over 24 hours and investigated relationships between diurnal activity patterns and mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Methods

One hundred and sixty-one older adults (26 with MCI) living alone (age = 78.9 ± 9.2) were included from 2 study cohorts—the Oregon Center for Aging & Technology and the Minority Aging Research Study. Indoor room activities were measured by the number of trips made to rooms (bathroom, bedroom, kitchen, living room). Trips made to rooms (transitions) were detected using passive infrared motion sensors fixed on the walls for a month. Latent trajectory models were used to identify distinct diurnal patterns of room activities and characteristics associated with each trajectory.

Results

Latent trajectory models identified 2 diurnal patterns of bathroom usage (high and low usage). Participants with MCI were more likely to be in the high bathroom usage group that exhibited more trips to the bathroom than the low-usage group (odds ratio [OR] = 4.1, 95% CI [1.3–13.5], p = .02). For kitchen activity, 2 diurnal patterns were identified (high and low activity). Participants with MCI were more likely to be in the high kitchen activity group that exhibited more transitions to the kitchen throughout the day and night than the low kitchen activity group (OR = 3.2, 95% CI [1.1–9.1], p = .03).

Conclusions

The linkage between bathroom and kitchen activities with MCI may be the result of biological, health, and environmental factors in play. In-home, real-time unobtrusive-sensing offers a novel way of delineating cognitive health with chronologically-ordered movement across indoor locations.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s, Functional performance, Latent trajectory model, Neurological disorders

Human activities follow a high degree of consistency in both the spatial (geographic location) and temporal (time of day) routines. Many indoor (eg, sleep (1), mealtime (2)) and outdoor activities (3,4) occur at certain locations (bedroom, kitchen, grocery store) during certain periods of time (morning, afternoon, night). The consistency of spatiotemporal routines plays a significant role in regulating individual physiological function, maintaining physical fitness (5), and enhancing social engagement (6). Consistent activity patterns also help to maintain cognitive function. For example, it helps in sustaining cognitive alertness (7) and prospective memory for key events (eg, medication taking) (8). Unfortunately, as one ages, the spatiotemporal routines of activities become more susceptible to cognitive changes (9). With regard to temporal changes, shifting bedtimes and wake times are observed in later life, especially in those with Alzheimer’s disease (1,10). With regard to spatial changes, the amount of time spent outdoors is reduced when older adults develop mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia (11,12). Much of the observational data investigating spatial change is based on self-reported diaries or assessments (13–15) that have demonstrated some weaknesses (eg, recall-bias, low spatiotemporal resolution) (16,17). These approaches are limited in their ability to capture people’s specific locations in real-time within their homes. Given the limitations of observations of human activity regularity and the potential disruption to these patterns with aging, MCI, and dementia, further understanding these activities with greater spatiotemporal resolution—when and where an older adult is transitioning to within their home over time—is an important opportunity to detect meaningful transitions in function (4,18–20).

We have employed a ubiquitous sensing paradigm to capture spatiotemporal routines at home consisting of an unobtrusive, remote sensor-based platform installed in real-world homes in order to measure the frequency of trips they make between rooms within each hour over the day (21). To date, many proof-of-concept studies have used motion-sensing technology to collect location data in a controlled laboratory environment (19). Due to the high complexity of residential layouts and the heterogeneity of technology in real-world research, few studies have been able to accurately link spatiotemporal routines with cognitive impairment and aging in real-world homes. The platform we established, described in detail elsewhere (22), has addressed the above gaps by standardizing installation protocols, testing beta homes before employing the platform, and increasing the scalability to diverse environments across regions over time.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to estimate spatiotemporal patterns of daily routines in older adults, specifically the number of trips made to 4 major rooms (bathroom, bedroom, kitchen, living room) using an unobtrusive and remote sensor-based system in personal residences and what patterns are associated with those with MCI. A latent group trajectory model approach was utilized for this study as it is well-suited as a mixture model that simultaneously estimates distinct trajectory patterns (latent trajectories) and the characteristics associated with each group (logistic or multinomial logit models). The estimation of routines contextualized by time- and space-specified reference values may form a general corpus of data for delineating which diurnal activity patterns are more labile or dominant when cognitive impairment is present. Detecting variation of these patterns of routines could then be used as markers of risk for dementia or as meaningful criteria for treatment efficacy in intervention studies.

Method

Research Design

Study participants were from the Oregon Center for Aging and Technology (ORCATECH) in Portland, OR (22,23) and the Minority Aging Research Study (MARS) at Rush University in Chicago, IL. ORCATECH has led longitudinal studies examining the use of unobtrusive in-home sensing technology to detect cognitive decline in community-dwelling older adults (24–28). The MARS is a longitudinal cohort study of decline in cognitive function in older African Americans (29). Study approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Oregon Health & Science University (IRB #2765, #17123, #4089) and Rush University (IRB # L03030302). All participants provided written informed consent. Data collected after April 2020 (Coronavirus Disease 2019, COVID-19 pandemic) were excluded. The most recent month of available data for each participant was used for the analysis.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

For the ORCATECH cohort, inclusion criteria were age equal to or above 57, living in a residence larger than a single-room, living either alone or with a spouse/partner, and without dementia (Montreal-Cognitive Assessment [MoCA] > 18 (30) or Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score > 24; and Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR] score ≤ 0.5). To be eligible in the MARS study, participants had to self-report race as African American, be 65 years of age or older, and not have a diagnosis of dementia or be taking dementia medications. Households needed to have a reliable broadband internet connection. For the current study, exclusion criteria for both studies included more than 2 people living in the participant’s residence or a condition upon enrollment that would limit their physical participation in the study (eg, wheelchair bound). Inclusion criteria for the current study included any ORCATECH or MARS enrolled participant who lived alone to ensure detected activity/motion was attributable to a single individual. A total of 203 single-person homes were eligible for this study with 198 unique participants (5 participants had moved once). After excluding participants with missing clinical data (n = 5) and/or incomplete data (less than half a month of data) due to technical issues, a total of 161 homes/participants were included in the analysis. There was no difference in age, sex, and education distributions between those included in this study (n = 161) and those excluded (n = 198–161 = 32).

Measures

Spatiotemporal patterns of routines at home

Passive infrared (PIR) motion sensors (www.nycesensors.com/product/motion-sensor) were used to detect when a study participant was present in a given room using an established protocol (22,23). The motion sensors were placed in every room of the home (eg, bathroom(s), bedroom(s), kitchen(s), living room(s)). The PIR motion sensors reported the beginning time and ending time of detected presence within each room of the home. Contact sensors (https://www.nycesensors.com/product/door-window-sensor) were installed on all egress doors for the home to detect door openings and time out-of-home (in conjunction with the PIR motion sensors).

We derived the number of trips made to each room per hour for each room (primary bathroom where person showered or bathed, primary bedroom where person commonly slept at night, kitchen, living room). The number of trips made to each room during a given hour was estimated as the number of presence events detected in the given room following the presence in a different room during the hour. The time spent out-of-home was calculated by the time difference between 2 door openings when no one was home (as estimated using the PIR motion sensors).

For example, consider the following time stamps for the beginning of presence detected by the PIR motions in various rooms for 1 participant between 11 am and noon: Bathroom (11:03:13 am) → bedroom (11:05:35 am) → bathroom (11:06:46 am) → door sensor (11:10:33 am) → door sensor (11:31:35 am) → bedroom (11:59:21 am). In this example, the participant made 2 trips to the bedroom at 11:05:35 am and 11:59:21 am, respectively. The total time the participant was out-of-home between 11 am and 12 noon was 21 minutes and 2 seconds (door [11:31:35 am]–door [11:10:33 am]). A more in-depth description of the algorithm used to extract room activities and out-of-home activities from the PIR motions sensors was discussed in a previous article (11).

During the study, participants also completed a health and life activity questionnaire that was automatically emailed to them once weekly. The questionnaire collected information such as whether they had any overnight visitors during the week or whether they were away from home overnight. In order to only include observations from the study participants, data were excluded from days when overnight visitors were reported or they were away from home overnight (3.0% of days). Days with a sensor malfunction were excluded from the analysis (3.1% of days). Finally, daily data were averaged across the month of data collection for the analysis.

Mild cognitive impairment

For the ORCATECH cohort, MCI was operationalized by the CDR score assessment tool collected at an annual assessment. A CDR score of 0.5 was used to designate MCI status. For the MARS study, MCI was determined using a 2-stage process by an experienced clinician. First, an algorithm was used to rate impairment in 5 cognitive domains. Second, after reviewing all cognitive data, occupation, years of education, and ratings of motor and sensory problems, a neuropsychologist made the final diagnosis.

Covariates

Participant characteristics (age, gender, race, years of education, gait speed, number of rooms at home) were collected at an annual assessment. Because gait speed has been associated with MCI (31) and might confound indoor room activity patterns, it was included in the models as a control variable. For the ORCATECH cohort, in-person observed gait speed was measured by a timed 4.6 m (15 foot) out and back gait test at a usual pace. The total time (seconds) to complete the usual paced walk was recorded, with less time indicating a faster gait speed. For the MARS study, gait speed was based on the time to walk 8 feet. Gait speed measures from the 2 studies were harmonized using the same unit (cm/s). Because the total number of rooms in the home may influence the number of trips made to each room, it was controlled for in the models. The amount of time spent out of the home may influence the number of trips made to each room. Therefore, daily average amount of time out of the home was estimated (32) and controlled for in the model.

Analytical approach

Latent group trajectory models were used to identify underlying diurnal activity patterns for 4 outcomes (trips made to the primary bathroom, primary bedroom, kitchen, and living room). The latent group trajectory analysis has been widely used to identify underlying disease progressions or developmental processes from longitudinal data series (31,33,34). The latent group trajectory model is based on the premise that a set of observed repeated measures collected from an individual over time can be used for modeling distinct, unobserved subgroups or patterns in data that give rise to the repeated measures. Here we adopt the latent trajectory analysis to model the routine patterns across twenty-four 1-hour periods in a day.

Instead of using a 2-stage (“classify-analyze”) approach that assigns subjects to the most likely latent subgroup and then treats the latent class variable “Ci” as though it were observed without error to make inferences about the relationship between C and covariates Z, we used an approximation procedure proposed by Roeder et al. (35). The proposed procedure allows models for C|Z to be fit using available software for generalized linear models and provides a conservative approximation for testing hypotheses of the association between Z and C while circumventing issues associated with the 2-step approach.

Compared with the single-group trajectory analysis, the latent group trajectory model allows for the possibility of latent subgroups assumed to have different distributions of time stable covariates Zi. The conditional distribution of the observed data Yi for subject i, given Zi is estimated with the model of latent subgroups and the model of trajectory patterns simultaneously:

where Yit = [0,24] is the trajectory of individual i’s number of trips to each room (eg, bathroom) over the 24-hour time interval, Zi is the time stable risk factors for subject i, and Ci denotes the group membership for subject i out of K trajectory groups. The Pr(C = k|z) is modeled as a K-outcome logit with covariate Z (35).

In this study, SAS procedure PROC TRAJ was used for the analysis (33,34). This procedure ran 2 models simultaneously as discussed above. First, a censored normal model was used to model the conditional distribution of data (33). The Bayesian information criterion was used to first select the best fitting model in terms of the number of latent trajectory groups and their patterns. The trajectories of the latent groups were calculated by a polynomial function of time (hour of the day over 24 hours). Once the number of latent trajectory and patterns was identified, a K-outcome logit model was simultaneously estimated to examine the associations of covariates including MCI with the probability of membership in the homogeneous latent groups. We compared the probabilities of membership into each of the latent groups that were indicated by the coefficient estimates in the model for participants with and without MCI. Because higher-order polynomial functions may lead to data overfitting, we conducted sensitivity analysis for each model using a quadratic polynomial function model. Baseline characteristics (age, gender, years of education, race), physical function (gait speed log-transformed), and environmental factors (the number of rooms in home, total time out-of-home) were controlled for in the models.

Results

A total of 4114 days of sensor data were included in the analysis across 161 participants. On average, 25.6 (SD = 5.3) days of data were analyzed per participant. Data from each of the twenty-four 1-hour periods in a day were averaged across all the days in the month of data collection per participant. The average hourly data (twenty-four 1-hour periods of data × 161 participants) were used in the latent trajectory models. Among 161 participants across study cohorts, 26 (16.15%) participants met the criteria for MCI. The proportion of females and years of education showed a significant group difference. The MCI group had fewer females and less years of education than the non-MCI group (Table 1). The proportion of individuals with MCI was not different between the ORCATECH cohort and the MARS study (p = .06). On average, participants in the MARS study were 3.4 years younger (p = .01), had a slower gait speed (73.98 cm/s vs 52.17 cm/s; p < .01), and had spent less time out-of-home per day (46 minutes less; p = .03) than the ORCATECH cohort.

Table 1.

Participant Baseline Characteristics

| All | Non-MCI | MCI | t-Statistics/χ 2-Statistics | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics, n (%) | 161 (100) | 135 (83.85) | 26 (16.15) | |||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 78.87 | (9.18) | 79.13 | (8.96) | 77.52 | (10.33) | t (159) = 0.82 | .42 |

| Female, n (%) | 119 | (73.91) | 104 | (77.04) | 15 | (57.69) | χ 2(1) = 4.23 | .04 |

| Race (White), n (%) | 120 | (74.53) | 100 | (74.07) | 20 | (76.92) | χ 2(1) = 0.09 | .76 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 15.60 | (2.85) | 15.80 | (2.69) | 14.54 | (3.44) | t (159) = 2.09 | .04 |

| Walking speed (cm/s), mean (SD) | 69.92 | (21.40) | 70.40 | (21.03) | 67.44 | (23.52) | t (159) = 0.64 | .52 |

| Number of rooms in the home, n (%) | 6.02 | (2.20) | 6.10 | (2.17) | 5.58 | (2.39) | t (159) = 1.12 | .27 |

| Spatiotemporal routines, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Total number of bathroom trips per day | 17.19 | (8.19) | 16.87 | (8.08) | 18.87 | (8.74) | t (159) = −1.14 | .26 |

| Total number of bedroom trips per day | 23.27 | (14.60) | 23.08 | (14.57) | 24.28 | (15.01) | t (159) = −0.38 | .70 |

| Total number of kitchen trips per day | 34.38 | (23.11) | 33.54 | (23.16) | 38.75 | (22.77) | t (159) = −1.05 | .29 |

| Total number of living room trips per day | 36.98 | (23.75) | 36.40 | (23.63) | 39.99 | (24.62) | t (159) = −0.70 | .48 |

| Total time out-of-home in hours per day, mean (SD) | 2.85 | (1.82) | 2.87 | (1.82) | 2.71 | (1.83) | t (159) = 0.41 | .68 |

| Days of data per individual, mean (SD) | 25.55 | (5.28) | 25.70 | (5.14) | 24.81 | (6.00) | t (159) = 0.78 | .43 |

Note: MCI = mild cognitive impairment.

In terms of the 4 room activity outcomes, there were no significant differences between MCI and non-MCI groups with regard to the daily average number of trips to each room in the home (Table 1). Even though the mean number of trips to each room per day was not statistically different, there may be smaller or larger differences with respect to the specific time of the day that the trips occurred. In order to identify whether there were distinct diurnal trajectories associated with MCI, we ran latent trajectory models. Because we did not find a meaningful relationship between living room diurnal patterns and MCI (p = .42), we only presented the results of the other 3 outcomes below.

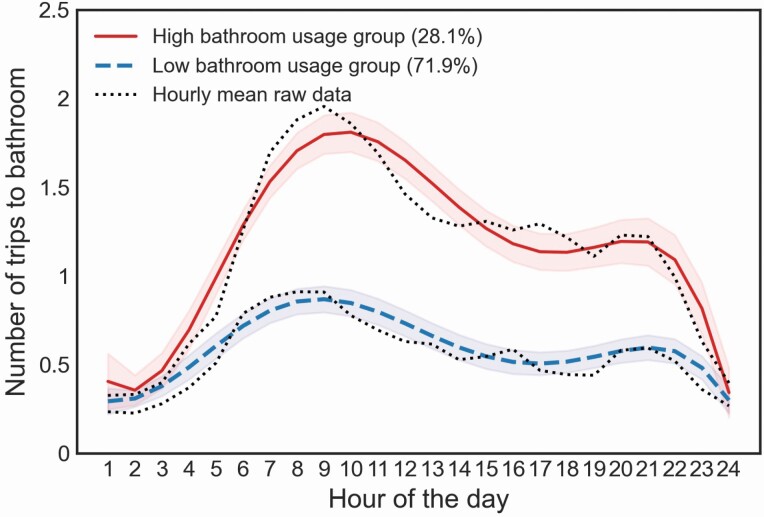

Number of Trips Made to the Bathroom

Latent trajectory models (with quintic function) identified 2 groups based on diurnal activity patterns related to trips made to the primary bathroom. Based on the trajectories of groups, we classified them as “high” and “low” bathroom usage groups (Figure 1). The “high” bathroom usage group had a daily activity peak at 10 am (1.8 trips) and a trough at midnight (0.34 trips). The “low” bathroom usage group had a peak around 9 am (0.87 trips) and a trough at 1 am (0.29 trips). The “high” bathroom usage group was characterized by a bimodal-shaped pattern with more transitions made to the bathroom compared with the “low” bathroom usage group, which exhibited a similar bimodal shape but with less transitions made in and out of the bathroom. Logistic regression model identified that older adults with MCI were more likely to belong to the “high” bathroom usage group than those in the non-MCI group, controlling for age, gender, education, race, gait speed, and the number of rooms (β = 1.42; p = .02; Table 2). Given the average levels of covariates (age, gender, education, race, number of rooms, gait speed), the probability of belonging to the “high” bathroom usage group was 58% (95% CI 50.4%–65.6%) among MCI but only 25% (95% CI 18.3%–1.7%) in those with normal cognition. That is, the probability of belonging to the “high” bathroom usage group was 2.3 times higher among those with MCI than those with normal cognition. Results remained significant after controlling for time out-of-home (β = 1.33; p = .02). The use of a quadratic function in the latent trajectory model showed the same significant result (p = .01; Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1.

Trips to the bathroom based on latent trajectory analyses.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Models Showing the Associations Between Number of Trips to Rooms and MCI Status

| (a) Trips to the Bathroom | (b) Trips to the Bedroom | (c) Trips to the Kitchen | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Bathroom Usage (n = 45) | Low Bathroom Usage (n = 116): Reference Group Coefficient | Frequent Trips to Bedroom (n = 51) | Less Trips to Bedroom (n = 110): Reference group coefficient | High Kitchen Activity (n = 42) | Low Kitchen Activity (n = 119): Reference Group Coefficient | |||||||

| Coefficient β | SE | p-Value | Coefficient Beta | SE | p-Value | Coefficient β | SE | p-Value | ||||

| Intercept | −9.36 | 5.81 | 0.11 | 0 | −1.73 | 4.53 | 0.70 | 0 | −7.29 | 4.80 | 0.13 | 0 |

| Age at baseline | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.64 | 0 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0 |

| Female | 1.53 | 0.63 | *0.02 | 0 | 1.18 | 0.50 | *0.02 | 0 | 1.70 | 0.59 | *0.004 | 0 |

| Education in years | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.60 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.88 | 0 | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.46 | 0 |

| Race (White) | −0.17 | 0.52 | 0.75 | 0 | −0.38 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0 | −0.17 | 0.54 | 0.75 | 0 |

| Number of rooms | 0.001 | 0.10 | 0.99 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.68 | 0 | −0.02 | 0.10 | 0.85 | 0 |

| Gait speed (log) | 1.22 | 0.92 | 0.18 | 0 | 0.27 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0 | 1.71 | 0.82 | *0.04 | 0 |

| MCI diagnosis | 1.42 | 0.60 | *0.02 | 0 | 1.03 | 0.52 | 0.05 | 0 | 1.15 | 0.54 | *0.03 | 0 |

| Model fit statistics | ||||||||||||

| BIC | −3192.87 | −4674.53 | −5802.85 | |||||||||

| AIC | −3160.51 | −4643.71 | −5770.50 | |||||||||

| Likelihood ratio | χ 2 = 16.30 (p = .02) | χ 2 = 13.05 (p = .07) | χ 2 = 24.03 (p = .001) | |||||||||

Notes: AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; SE = standard error.

*p < .05.

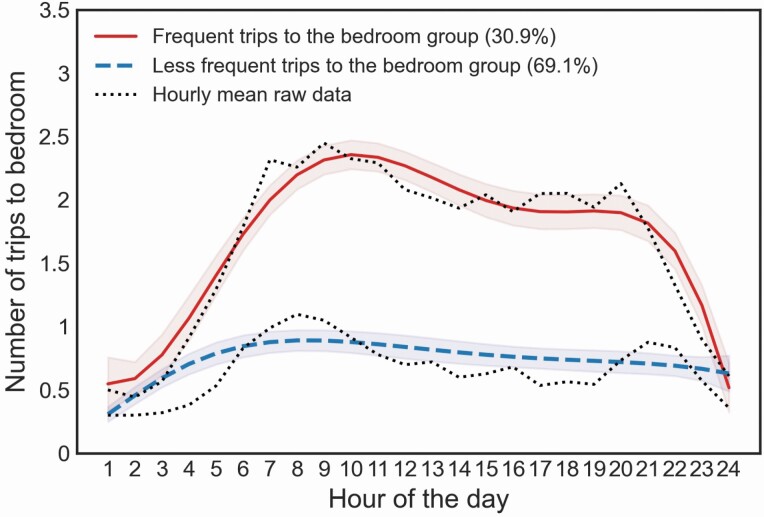

Number of Trips Made to the Bedroom

Latent trajectory models (with quintic function) identified 2 groups based on diurnal activity patterns related to trips made to the primary bedroom. Based on the trajectories, we classified them as “frequent” and “less frequent” bedroom trip groups (Figure 2). The “frequent” bedroom trip group showed a daily activity peak at 10 am (2.4 trips) and a trough at midnight (0.5 trips), whereas the “less frequent” bedroom trip group showed a peak at 8 am (0.9 trips) and a trough at 1 am (0.3 trips). The “frequent” bedroom trip group was characterized by a bimodal-shaped pattern with more transitions made to the bedroom compared with the “less frequent” bedroom trip group, which exhibited a curve that slowly increased in the morning and plateaued from 8 am until midnight. Participants with MCI had a similar likelihood of being in the “frequent” bedroom trip group along with those in the non-MCI group, controlling for age, gender, years of education, race, gait speed, and the number of rooms (β = 1.03; p = .047≈.05; Table 2). Given the average levels of covariates (age, gender, education, race, number of rooms, gait speed), the probability of belonging to the “frequency” bedroom trip group was 61% (95% CI 53.6%–68.4%) among MCI but only 36% (95% CI 28.6%–43.4%) in those with normal cognition. Results remained insignificant after controlling for time out-of-home (β = 1.02; p = .05). The use of a quadratic function in the latent trajectory model showed a similar insignificant result (p = .09; Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 2.

Trips to the bedroom based on latent trajectory analyses.

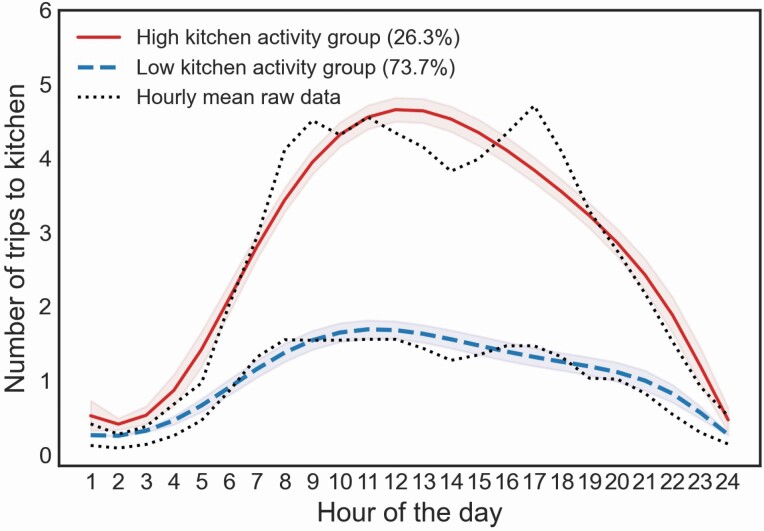

Number of Trips Made to the Kitchen

Latent trajectory models (with quintic function) identified 2 groups based on diurnal activity patterns related to trips made to the kitchen. Based on the trajectories, we classified them as “high” and “low” kitchen activity groups (Figure 3). The “high” kitchen activity group had a peak at noon (4.7 trips) and a trough at 2 am (0.4 trips). The “low” kitchen activity group had a daily activity peak at 11 am (1.7 trips) and a trough at 2 am (0.3 trips). The high kitchen activity group was characterized by an asymmetric inverted u-shaped pattern with more transitions made to the kitchen compared with the “low” kitchen activity group, which exhibited a flattened inverted u-shaped pattern with less transitions made in and out of the kitchen (Figure 3). Participants with MCI were more likely to be in the “high” kitchen activity group when compared with those in the non-MCI group, controlling for age, gender, race, years of education, gait speed, and the number of rooms (β = 1.15; p = .03; Table 2). Given the average levels of covariates (age, gender, education, race, number of rooms, gait speed), the probability of belonging to the “high” kitchen activity group was 57% (95% CI 49.4%–64.6%) among MCI but only 30% (95% CI 22.9%–37.1%) in those with normal cognition. That is, the probability of belonging to the “high” kitchen activity group was approximately 2 times higher among those with MCI than those with normal cognition. Results remained significant after controlling for time out-of-home (β = 1.18; p = .04). The use of a quadratic function in the latent trajectory model showed the same significant result (p = .03; Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 3.

Trips to the kitchen based on latent trajectory analyses.

Discussion

Using unobtrusive in-home sensing technology, we monitored indoor room activities over a month and investigated relationships between diurnal room activity patterns and MCI. Our findings suggested that (i) an in-home, real-time unobtrusive-sensing platform offers a way of detecting chronological-ordered movement across indoor geographic locations and (ii) individuals with MCI may follow a different spatiotemporal pattern of routines at home compared with non-MCI individuals. Looking at the total number of trips to rooms at a day level, there was no difference between MCI and non-MCI individuals. Yet, when taking into account the hourly latent behavioral patterns, the presence of MCI exerted important effects on the diurnal patterns of routines over 24 hours. This suggests that averaging data at a day level without considering hourly effects may lose critical information to delineate a person’s cognitive health. These nuanced differences in spatiotemporal routines would not be possible to detect without the intradaily, high-resolution data provided by continuous unobtrusive home-based activity sensing.

Our results were similar to a small case study, in which Urwyler et al. (19) compared ADL routines in 10 older adults with either normal cognition or dementia. Based on activity maps, the older adults with dementia spent more time in and made more trips to the bathroom and kitchen than the older adults with intact cognition. Additionally, they found that there were more grooming, toileting, cooking, and eating events in those with dementia than those with intact cognition. Our study substantially builds on this initial case study using a much larger sample size and by examining participants in the earlier phase of cognitive impairment (eg, MCI). Our data suggest that similar patterns of spatiotemporal routines were already occurring even earlier in the disease course.

Potential Mechanisms Associating Kitchen Activity and MCI

The relationship between kitchen activity and MCI could be explained by biological clocks (5,36,37). For example, decreased light perception associated with aging and dementia may influence melatonin secretion (38). Studies have found that older adults with cognitive impairment reported more hunger (alteration of nutrient absorption and metabolism) (38), a greater likelihood to seek food between meals (more snacking behaviors) (39), changes in physiological function like increases in sensory thresholds (40), or preferences for sweet or fatty tastes (39). All these possibilities may lead to more transitions to the kitchen. More transitions to the kitchen may also be influenced by medication. For example, more chronic diseases and ensuing polypharmacy associated with aging and cognitive impairment may exacerbate hypermetabolism and alter eating and drinking behavior (41). Furthermore, engaging in multistep tasks, such as navigating a television or organizing and preparing meals, requires multiple cognitive processes (attention, working memory, executive skills) that older adults with MCI may experience difficulties with and exhibit more transitions in and out of the kitchen (42). Cautiously, these hypotheses were made based on the assumption that a kitchen is a place for eating, drinking, and cooking behaviors. Yet a kitchen may serve multipurposes that would complicate the relationship between kitchen activities and cognitive health (eg, social, instrumental-type activities, etc.).

Potential Mechanisms Associating Bathroom Activity and MCI

More trips to the bathroom exhibited in the MCI group may be the result of several factors. More transitions to the bathroom may be related to urinary tract changes, which have been reported in older adults with more comorbidity, cognitive impairment, or females (43,44). This may explain why we observed that females were more likely to be in the high bathroom usage group. Although our cohorts did not collect specific information about medical history related to urinary or bowel disease, this could be explored in future studies. In addition, bathroom usage may be related to food choices and dietary options. The preferences for sweet or fatty tastes (32) reported in those with MCI may create a blood sugar spike leading to individuals seeking out liquids in the kitchen and making trips to the bathroom more often (45).

We did not find an association between living room diurnal patterns with MCI status, and the relationship between bedroom diurnal patterns and MCI was marginally significant (p = .047–.05). Although older adults may make trips to the bedroom or living room for many purposes such as taking a nap, watching television, or using computer or tablets, detecting specific instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) performed by older adults would be valuable. The use of other types of sensors and nonsensor-based tools/software would provide precise estimation of the performance of various IADLs including bed mats for sleep, automobile sensors for driving patterns (26), or software installed on the digital devices to monitor computer and laptop usages (46).

One of the covariates, gender, showed statistical significance in the models. Potentially, this may be related to sex differences in diurnal or circadian rhythms, such as known effects of gonadal steroids on melatonin that require further research (47). Potentially, this finding may also be related to gender differences in arranging their routines or gender-specific interests in IADLs. In our study cohort analysis, we also found that the MARS participants, all African Americans, had less time out-of-home compared with the ORCATECH cohort. Reasons for this are uncertain. Inclusion of a larger sample size and information on health, regions, social resources, and other factors associated with out-of-home time is needed to examine these and other possibilities.

There were limitations to this study. We only included single-person homes. In 2019, over 28% of people over age 65 (14.7 million) in the United States lived alone and they are at a greater risk for MCI or dementia compared with those living with another person (48). However, those living in multi-resident dwellings should also be included in future studies once data analysis approaches are developed to attribute activity at the level of the individual. In addition, there is a wide variety of residential settings that could be considered (eg, rural vs suburban vs urban, variable home spaces, variable access to transportation and other services). Although our study participants were comprised of a mixture of rural, urban, and low-income older adults, we did not have further diversity that would allow us to explore these factors more broadly. Furthermore, the kitchen serves multiple functions beyond eating. Some older adults with smaller homes may use their kitchen more as a living space where they sit and pay bills, talk on the phone, and so forth. This study did not allow us to know what is being done in each room other than the bathroom, where hygiene and toilet-use activities are more likely occurring. In this study, the square footage of each house is unknown. Instead, we used the number of rooms as a proxy for the size of the residence. Reassuringly, covarying for the number of rooms did not affect the results. In addition, external factors such as weather, seasons, social resources, and income could influence diurnal patterns of routines. Although we controlled for time out of the home as a proxy for seasonal and weather effects, future longitudinal analyses should explore contextual factors in more detail. Last, we urge future studies to explore within-person and between-person variations using other analytical approaches like multilevel models to take into the consideration of 24-hour observations nested in individuals over time.

In conclusion, using an unobtrusive passive sensing platform, high-resolution data were collected from real-world homes, providing ecologically valid spatiotemporal patterns during daily life. The ORCATECH technology platform has successfully been deployed to hundreds of homes encompassing diverse populations in diverse locations (22). Detailed manuals and instructions (including video tutorials) have been developed, so that study personnel and/or study participants can install the technology platform without any special technical expertise. Although access to broadband internet is a requirement for using the platform, cellular hotspots have been successfully utilized (22). The ability to collect longitudinal data across several months or several years allows the detection of gradual changes in an individual’s physical activity and cognitive health (25,31). The high-frequency nature of the data collected by the ORCATECH technology platform has also shown promise in reducing the sample sizes need for clinical trials (25). Our multidimensional unobtrusive assessment approach provides a means to detect nuanced differences in daily activities in those at risk for dementia, affording a novel way to detect, as well as monitor the progression of MCI in both natural history and intervention studies (eg, chronotherapy, drug trials) (49,50). Data collected from this approach can also be used in companion with subjective or caregiver-reported changes in routines and IADLs to improve the current adjudication of MCI.

Funding

The work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (P30AG024978, R01AG024059, P30-AG008017, and U2C AG054397 to J.A.K.; RF1AG22018, P3010161, and R01AG17917 to L.L.B.; P30AG024978 Roybal Pilot and P30AG066518-01 Development Program to C.-Y.W.; P30AG024978-15 Roybal Pilot and P30AG066518-02 Development Program to M.M.L.); the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development (IIR 17-144 to L.C.S.); the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR002369; KL2TR002370 to K.W.); the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (KL2TR002370 to K.W.); and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory: Hartford Gerontological Center Interprofessional Award to M.M.L.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank participants in the ORCATECH Life Lab (OLL) study, the Collaborative Aging Research Using Technology (CART) initiative, and the Minority Aging Research Study (MARS).

Contributor Information

Chao-Yi Wu, Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), School of Medicine, Portland, Oregon, USA; Oregon Center for Aging & Technology (ORCATECH), OHSU, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Hiroko H Dodge, Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), School of Medicine, Portland, Oregon, USA; Oregon Center for Aging & Technology (ORCATECH), OHSU, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Sarah Gothard, Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), School of Medicine, Portland, Oregon, USA; Oregon Center for Aging & Technology (ORCATECH), OHSU, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Nora Mattek, Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), School of Medicine, Portland, Oregon, USA; Oregon Center for Aging & Technology (ORCATECH), OHSU, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Kirsten Wright, Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), School of Medicine, Portland, Oregon, USA; Oregon Center for Aging & Technology (ORCATECH), OHSU, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Lisa L Barnes, Department of Neurological Sciences, Rush Medical College, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Rush Medical College, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Lisa C Silbert, Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), School of Medicine, Portland, Oregon, USA; Oregon Center for Aging & Technology (ORCATECH), OHSU, Portland, Oregon, USA; Department of Neurology, Veterans Affairs Portland Health Care System, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Miranda M Lim, Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), School of Medicine, Portland, Oregon, USA; Department of Neurology, Veterans Affairs Portland Health Care System, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Jeffrey A Kaye, Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), School of Medicine, Portland, Oregon, USA; Oregon Center for Aging & Technology (ORCATECH), OHSU, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Zachary Beattie, Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), School of Medicine, Portland, Oregon, USA; Oregon Center for Aging & Technology (ORCATECH), OHSU, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Author Contributions

C.-Y.W. planned the study, performed all statistical analyses, and wrote the paper. H.H.D. and Z.B. supervised the data analysis and contributed to revising the paper. J.A.K., L.L.B., L.C.S., K.W., and M.M.L. contributed to revising the paper. S.G. and N.M. extracted the data and contributed to revising the paper.

Conflict of Interest

J.A.K. has received research support awarded to his institution (Oregon Health & Science University) from the NIH, NSF, the Department of Veterans Affairs, USC Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute, Merck, AbbVie, Eisai, Green Valley Pharmaceuticals, and Alector. He holds stock in Life Analytics Inc. for which no payments have been made to him or his institution. Z.B. holds stock in Life Analytics Inc. for which no payments have been made to him or his institution. Other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Roenneberg T, Merrow M. The circadian clock and human health. Curr Biol. 2016;26(10):R432–R443. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kessler K, Pivovarova-Ramich O. Meal timing, aging, and metabolic health. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(8):1911. doi: 10.3390/ijms20081911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cochrane A, Robertson IH, Coogan AN. Association between circadian rhythms, sleep and cognitive impairment in healthy older adults: an actigraphic study. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2012;119(10):1233–1239. doi: 10.1007/s00702-012-0802-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khan T, Jacobs P. Prediction of mild cognitive impairment using movement complexity. IEEE J Biomed Heal Informatics. 2020;25(1):227–236. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2020.2985907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grandin LD, Alloy LB, Abramson LY. The social zeitgeber theory, circadian rhythms, and mood disorders: review and evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(6):679–694. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sekara V, Stopczynski A, Lehmann S. Fundamental structures of dynamic social networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(36):9977–9982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602803113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rawashdeh O, Maronde E. The hormonal Zeitgeber melatonin: role as a circadian modulator in memory processing. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:27. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hayes TL, Larimer N, Adami A, Kaye JA. Medication adherence in healthy elders: small cognitive changes make a big difference. J Aging Health. 2009;21(4):567–580. doi: 10.1177/0898264309332836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Musiek ES, Bhimasani M, Zangrilli MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM, Ju YS. Circadian rest-activity pattern changes in aging and preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(5):582–590. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leng Y, Musiek ES, Hu K, Cappuccio FP, Yaffe K. Association between circadian rhythms and neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(3):307–318. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30461-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Petersen J, Austin D, Mattek N, Kaye J. Time out-of-home and cognitive, physical, and emotional wellbeing of older adults: a longitudinal mixed effects model. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wettstein M, Wahl HW, Shoval N, et al. Out-of-home behavior and cognitive impairment in older adults: findings of the SenTra Project. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;34(1):3–25. doi: 10.1177/0733464812459373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baker PS, Bodner EV, Allman RM. Measuring life-space mobility in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(11):1610–1614. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hashidate H, Shimada H, Shiomi T, Shibata M, Sawada K, Sasamoto N. Measuring indoor life-space mobility at home in older adults with difficulty to perform outdoor activities. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2013;36(3):109–114. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0b013e31826e7d33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stalvey BT, Owsley C, Sloane ME, Ball K. The life space questionnaire: a measure of the extent of mobility of older adults. J Appl Gerontol. 1999;18(4):460–478. doi: 10.1177/073346489901800404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. May D, Nayak US, Isaacs B. The life-space diary: a measure of mobility in old people at home. Int Rehabil Med. 1985;7(4):182–186. doi: 10.3109/03790798509165993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wild KV, Mattek N, Austin D, Kaye JA. “Are you sure?”: lapses in self-reported activities among healthy older adults reporting online. J Appl Gerontol. 2016;35(6):627–641. doi: 10.1177/0733464815570667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zylstra B, Netscher G, Jacquemot J, et al. Extended, continuous measures of functional status in community dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s and related dementia: infrastructure, performance, tradeoffs, preliminary data, and promise. J Neurosci Methods. 2018;300:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.08.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Urwyler P, Stucki R, Rampa L, Müri R, Mosimann UP, Nef T. Cognitive impairment categorized in community-dwelling older adults with and without dementia using in-home sensors that recognise activities of daily living. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42084. doi: 10.1038/srep42084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Akl A, Chikhaoui B, Mattek N, Kaye J, Austin D, Mihailidis A. Clustering home activity distributions for automatic detection of mild cognitive impairment in older adults. J Ambient Intell Smart Environ. 2016;8(4):437–451. doi: 10.3233/AIS-160385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Austin D, Cross RM, Hayes T, Kaye J. Regularity and predictability of human mobility in personal space. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e90256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beattie Z, Miller LM, Almirola C, et al. The collaborative aging research using technology initiative: an open, sharable, technology-agnostic platform for the research community. Digit Biomark. 2020;4(suppl 1):100–118. doi: 10.1159/000512208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaye J, Reynolds C, Bowman M, et al. Methodology for establishing a community-wide life laboratory for capturing unobtrusive and continuous remote activity and health data. J Vis Exp. 2018;2018(137): 1– 10. doi: 10.3791/56942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Silbert LC, Dodge HH, Lahna D, et al. Less daily computer use is related to smaller hippocampal volumes in cognitively intact elderly. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52(2):713–717. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dodge HH, Zhu J, Mattek NC, Austin D, Kornfeld J, Kaye JA. Use of high-frequency in-home monitoring data may reduce sample sizes needed in clinical trials. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seelye A, Mattek N, Sharma N, et al. Passive assessment of routine driving with unobtrusive sensors: a new approach for identifying and monitoring functional level in normal aging and mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;59(4):1427–1437. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seelye A, Mattek N, Sharma N, et al. Weekly observations of online survey metadata obtained through home computer use allow for detection of changes in everyday cognition before transition to mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(2):187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.07.756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Austin J, Klein K, Mattek N, Kaye J. Variability in medication taking is associated with cognitive performance in nondemented older adults. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017;6:210–213. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barnes LL, Shah RC, Aggarwal NT, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. The minority aging research study: ongoing efforts to obtain brain donation in African Americans without dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9(6):734–745. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dodge HH, Mattek NC, Austin D, Hayes TL, Kaye JA. In-home walking speeds and variability trajectories associated with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2012;78(24):1946–1952. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318259e1de [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petersen J, Austin D, Kaye JA, Pavel M, Hayes TL. Unobtrusive in-home detection of time spent out-of-home with applications to loneliness and physical activity. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2014;18(5):1590–1596. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2013.2294276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001;29(3):374–393. doi: 10.1177/0049124101029003005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones BL, Nagin DS. Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociol Methods Res. 2007;35(4):542–571. doi: 10.1177/0049124106292364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roeder K, Lynch KG, Nagin DS. Modeling uncertainty in latent class membership: a case study in criminology. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(447):766–776. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Golombek DA, Rosenstein RE. Physiology of circadian entrainment. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(3):1063–1102. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00009.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fostinelli S, De Amicis R, Leone A, et al. Eating behavior in aging and dementia: the need for a comprehensive assessment. Front Nutr. 2020;7:604488. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.604488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Evans C. Malnutrition in the elderly: a multifactorial failure to thrive. Perm J. 2005;9(3):38–41. doi: 10.7812/tpp/05-056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ikeda M, Brown J, Holland AJ, Fukuhara R, Hodges JR. Changes in appetite, food preference, and eating habits in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73(4):371–376. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.4.371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Amarya S, Singh K, Sabharwal M. Changes during aging and their association with malnutrition. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;6(3):78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcgg.2015.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pilgrim AL, Robinson SM, Sayer AA, Roberts HC. An overview of appetite decline in older people. Nurs Older People. 2015;27(5):29–35. doi: 10.7748/nop.27.5.29.e697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jekel K, Damian M, Storf H, Hausner L, Frölich L. Development of a proxy-free objective assessment tool of instrumental activities of daily living in mild cognitive impairment using smart home technologies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52(2):509–517. doi: 10.3233/JAD-151054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Na HR, Cho ST. Relationship between lower urinary tract dysfunction and dementia. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2020;19(3):77–85. doi: 10.12779/dnd.2020.19.3.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ogama N, Yoshida M, Nakai T, Niida S, Toba K, Sakurai T. Frontal white matter hyperintensity predicts lower urinary tract dysfunction in older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(2):167–174. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Donini LM, Poggiogalle E, Piredda M, et al. Anorexia and eating patterns in the elderly. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Seelye A, Hagler S, Mattek N, et al. Computer mouse movement patterns: a potential marker of mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2015;1(4):472–480. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cipolla-Neto J, Amaral FG, Soares JM Jr, et al. The crosstalk between melatonin and sex steroid hormones. Neuroendocrinology. 2021: 1– 15. doi: 10.1159/000516148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Administration for Community Living. 2019 Profile of Older Americans. Washington, DC: Administration on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Landry GJ, Liu-Ambrose T. Buying time: a rationale for examining the use of circadian rhythm and sleep interventions to delay progression of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:1–21. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wirz-Justice A, Bromundt V, Cajochen C. Circadian disruption and psychiatric disorders: the importance of entrainment. Sleep Med Clin. 2009;4(2):273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2009.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.