Abstract

Human cells tightly control their dimensions, but in some cancers, normal cell size control is lost. In this study we measure cell volumes of epithelial cells from human lung adenocarcinoma progression in situ. By leveraging artificial intelligence (AI), we reconstruct tumor cell shapes in three dimensions (3D) and find airway type 2 cells display up to 10-fold increases in volume. Surprisingly, cell size increase is not caused by altered ploidy, and up to 80% of near-euploid tumor cells show abnormal sizes. Size dysregulation is not explained by cell swelling or senescence because cells maintain cytoplasmic density and proper organelle size scaling, but is correlated with changes in tissue organization and loss of a novel network of processes that appear to connect alveolar type 2 cells. To validate size dysregulation in near-euploid cells, we sorted cells from tumor single-cell suspensions on the basis of size. Our study provides data of unprecedented detail for cell volume dysregulation in a human cancer. Broadly, loss of size control may be a common feature of lung adenocarcinomas in humans and mice that is relevant to disease and identification of these cells provides a useful model for investigating cell size control and consequences of cell size dysregulation.

Introduction

Many human cell types grown in culture display strict homeostasis for cell size [1]. Studies in model systems show that cells coordinate cell growth and division during the cell cycle to achieve proper size control [2–6] and correct size variation at a population level [7, 8]. Although there has been progress to uncover factors that modulate cell size in mammalian culture [7, 9, 10], it is not clear which pathways determine the cell size set point for most proliferating cells. An added hurdle is that perturbations to the volumes of cultured cells normally cause reduction in cell growth rates and a loss of fitness [11]. As a result, it has been challenging to ascertain the role of cell size regulation in tissue physiology and to characterize the consequences of altered cell size on function. In short, new models are required [12]. To date, there are no mammalian model cell systems that enable broadly tunable control of volume without transiently swelling cells in which to study the biological impacts of altered cell size.

In certain diseased cell states, such as cancer and diabetes, cells display loss of size regulation [1, 2]. Analysis of proliferative cells of various types of cancer suggest that they lose normal control of cell size, nucleus size, or nucleus:cytoplasmic volume ratio [13, 14]. Abnormal nucleocytoplasmic ratios are often indicative of cancerous transformation [12, 15–19]. Additionally, alterations in dimensions of cell or nucleus have been tied to epithelial-mesenchyme transition (EMT) and invasion [20], and stemness [14], and thus there is significant interest in how loss of cell size control may contribute to tumorigenesis. More generally, in non-cancer model systems, alterations in cell size are linked to changes in gene expression [21, 22].

Although the molecular pathways that regulate human cell sizes are poorly understood, a number of general hypotheses have been put forth to explain increases in nucleus and cell volume or nucleocytoplasmic ratio found in some cancers. As early as 1930, it was Levine and his contemporaries who linked what he referred to as “semi-giant” cells to the tetraploid karyotype, and suggested “giant” cells had very high ploidies [23]. More recent refinements to this concept that ploidy drives size dysregulation are that alterations in nucleus size or cell size relate to genomic instability of cancer cells and subsequent broad increases of ploidy and cytoplasmic output [24, 25]. Studies in culture systems have also linked increased DNA content to increased cell size [26, 27]. Separately, because it has been observed that cells may transiently enlarge through increases in water content, including during mitosis [28, 29], osmotic swelling is commonly hypothesized to explain cell volume dysregulation. Indeed, measurements of sizes of the diverse cell lines that comprise the NCI-60 panel [30] show cell volume increases generally increase with ploidy, although some interpret aneuploidy to be the driving factor [30, 31]. Further, cell swelling has been observed in senescent cells and is accompanied by a reduction in cytoplasmic protein content [32], thus it might be assumed that enlarged cells do not contribute to disease. We wondered whether cells might lose regulation of their cell size set point, and do so in the absence of the increased ploidy or cell swelling, while retaining or even increasing proliferative functions. If so, these cells might provide generalizable insights on causes and consequences of size dysregulation.

Analyses of cell size dysregulation in human cancers have relied on proxy model systems, or indirect or bulk measurements that do not address ploidy on a per-cell basis. Measurement of cell areas in two dimensions at moderate magnifications also limits the ability to detect alterations in nucleus and cell shape. 2D spherical approximations underestimate cell volume, because the equator is a small portion of a sphere; the more complex the shape, the less reliable the 2D approximation. Nandakumar et al. addressed 3D cell and nuclear volumes and DNA contents of preneoplastic esophageal and also breast cancer cells in suspension [24, 25]. In both cases, they observed greater volume and DNA content for cell lines originating from the more progressed disease state, suggesting a link between volume, ploidy, and cell size. Dolfi et al. have provided the most complete dataset relating cell volumes and ploidy by measuring the entire NCI-60 panel with a Nexcelom Cellometer™. Although groundbreaking in establishing that cell size dysregulation exists in tumor cells, these are bulk measurements that are not bona fide tumors. Thus, a major advance would be three-dimensional image reconstruction of tumors and object segmentation of specific cell types that is essential to accurately characterize alterations to the shapes and volumes of cells. Thus, in this study we sought to characterize the loss of homeostatic cell and organelle size control for a defined cell of origin in situ in 3D, within a human tumor.

By first analyzing digital histology databases [33, 34] and screening pathology H&E slides, we identified lung adenocarcinoma (LA) as a cancer type that likely contains a large variation of epithelial cell sizes. LA is the most prevalent form of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [35]. NSCLC is the number one cause of cancer deaths in the United States, and was expected to claim more than 130,000 lives in 2021 [36]. Morphological categorization remains the underlying foundation for the classification of subtypes of NSCLC, suggesting more high-resolution data may provide a benefit to the field of pathology [17, 18, 35, 37–41]. LA morphology is described by lepidic, papillary, acinar, micropapillary, and solid patterns of growth, and the disease has well-established mouse models [35, 42, 43]. Experiments in mice suggest LAs may arise from transformation of epithelial stem cells, called airway-type II (AT2) cells present in the lung alveoli [44]. These stem cells secrete surfactant proteins to prevent alveolar collapse and help to repair damaged lung tissue [43, 45–48]. In this study, we also discovered that these cells display a network of thin processes containing pro-surfactant protein. Within the clinic, two predominant genetic forms of LA, EGFR+ and KRAS+, are mutually exclusive [49]. Notably, data on DNA content for LA across all stages [18] suggested ploidy might only partially explain our preliminary observation of cell size dysregulation. Thus, LA seemed to be an ideal candidate for characterizing the loss of cell size regulation.

In this study, we set out to explore the extent, prevalence and staging of epithelial cell size dysregulation in situ via quantitative analysis of three-dimensional image reconstructions of LA tumor specimens. Additionally, we sought to determine the extent to which size dysregulation was explained by alteration of ploidy or osmotic swelling and to what extent cells of altered size proliferated and maintained homeostatic control of protein content and organelle size scaling. To do so, we characterized cell and organelle volumes and shapes of epithelial cells in situ within EGFR+ and KRAS+ types across three stages of tumor progression, and compare them to normal AT2 cells. Our results show vast enlargement of epithelial cell and nucleus volume are present in LA, irrespective of ploidy. The range of cell and nucleus volumes increases up to eight-fold and up to 80% of euploid cells display size dysregulation at specific stages. The mean size of proliferating epithelial cells in LA is greatly increased suggesting that these cells contribute to tumor progression. Further, these enlarged cells are not simply swollen and instead show homeostatic control of protein content and size scaling or organelles, including the nucleus, nucleolus and nuclear speckles, indicative of their function. Cell size variation is associated with tissue organization in these tumors and nuclear size variation was also present in a mouse model for the disease. Additionally, to validate the presence of cell size variation is a property of near-euploid cells, we developed a method to isolate and separate human epithelial cells from LAs on the basis of their cell sizes using flow cytometry. Our data suggest that broad dysregulation of cell size is a prevalent feature of LA and that these proliferating epithelial cells, which maintain macromolecular content and scale organelle sizes may be a useful model for investigating mechanisms of size control and the consequences of size variation.

Results

Human lung adenocarcinoma displays significant cell and nuclear volume dysregulation that can be measured in 3D by exploiting machine learning

Human lung alveoli are structured air sacs with lumens which are surrounded by an epithelium. This epithelial layer is composed alveolar type 1 (AT1) and type 2 (AT2) cells (Fig 1A) and lies on top of a thin stromal layer. AT2 cells fulfill the critical functions of secreting surfactants that are released into the lamina of the alveolus from multilamellar bodies, and are the resident stem cells of the alveolus [42, 44, 45, 47, 48, 50, 51]. AT1 cells differentiate from dividing AT2 cells that undergo a process of shaping and flattening to a 1 μm thickness and loss of surfactant protein expression [45]. LA is believed to result from an oncogenic event in dividing AT2 cells in mice, although evidence for this in humans is limited [44]. LA cells are known to overexpress cytokeratin 7 before they undergo additional transformations [52].

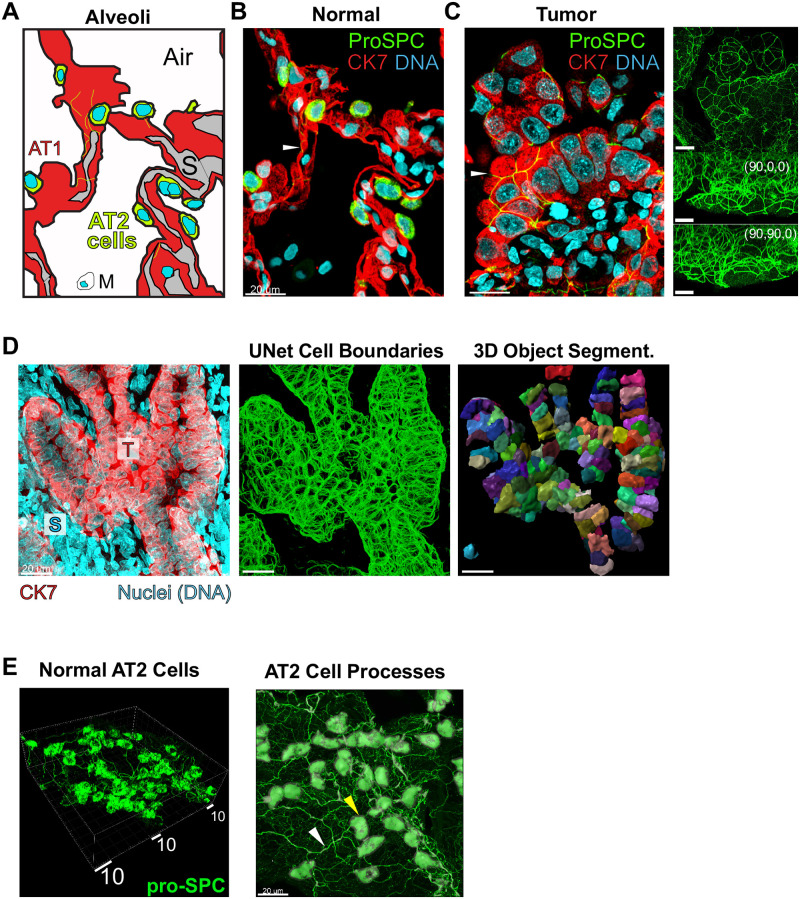

Fig 1. Human lung adenocarcinoma is characterized by dysregulation of cell and nuclear size.

63X images shown. A., schematized alveolus, related to B., showing AT2 cells (marker: proSPC, green), presumptive wide and flat AT1 cells, non-CK7-staining macrophage, M, and stroma, S. Epithelial cells express marker CK7, but weakly in AT2 cell bodies. B. and C., 5 μm z-projections of representative normal distant control alveoli, B., and representative EGFR+ LA tumor, AT2 cells marked by proSPC (green), C. Cytokeratin 7, CK7 (red); overexpressed in tumor cells. DNA stained by TO-PRO-3 (cyan). White arrows: thin cellular processes (shown in 1E, below). Right, full-stack max-intensity projections from each axis. Scale bars, 20 μm. Row D., 3D segmentation approach for tumor cells. Left, a high-density confocal stack often referenced during early development of our machine-learning algorithm. Middle, Machine Learning from CK7 staining predicts cell boundaries. Right, Commercial Imaris software fits cell boundaries, with rainbow coloring showing individually segmented cell surfaces. High-coverage case shown. E. Left, 3D rendering of AT2 cells (proSPC) showing thin cellular processes; right, processes shown with AT2 cell body segmentation (gray). White box shows perspective scale, 2 μm per small tick mark. Yellow arrow: AT2 cell body; white arrow: cellular process.

We first asked whether it was possible to distinguish LA cells from their proposed AT2 progenitors in whole-mount tumor sections and to reconstruct three dimensional morphologies. In doing so we reasoned it would be possible to identify alterations in cell and organelle dimensions in situ in the context of local tissue organization. We performed whole-mount immunofluorescence (IF) confocal imaging of formaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) [53] samples that comprised 150 μm-sections of pre-identified normal and LA patient specimens. FFPE is well-documented to undergo minor isotropic shrinkage over the length scale order of 1–100 μm relevant here, which depend on a given lab’s procedures [54]. However, it preserves cell and nuclear features and DNA content very well, while providing a route to deep image characterization of human samples that are already phenotyped, genotyped, and with well-defined treatment history [55]. To identify cell types in situ, we immunostained using antibodies specific to the unprocessed N-terminal region of prosurfactant protein C (proSPC), which is highly expressed in the cytoplasm of AT2 cells, and cytokeratin 7, which labels epithelial and LA cells with high sensitivity; it does not stain underlying stroma [42, 43, 48, 52, 56, 57]. To stain DNA for nucleus segmentation we used TO-PRO-3. For DNA content measurements we included stromal cell nuclei to establish normal baseline levels of DNA. At high magnification our image stack was typically ~135 x 135 x 60 μm [58].

Representative IF images of normal and LA specimens (Fig 1B and 1C) illustrate that delineation of AT2 and CK7-overexpressing tumor cells was straightforward and facilitated observation of novel cellular morphologies and changes to the cell size and shape. AT2 cells were easily identified as bright-green fluorescing cells (proSPC) mutually exclusive with the red channel in their cytoplasm (CK7), but bracketed by brightly red-fluorescing alveolar walls. These cells also have intense TO-PRO-3 DNA stains typical of cell nuclei (AT1 cells, Fig 1A shows a schematic). We observed AT2 cell bodies filled with dense green-fluorescing puncta, which mark multilamellar vesicles containing proSPC as expected for these secretory cells. Surprisingly, we also noticed that this protein marker extended into an interconnected network of thin “processes”, which to our knowledge have not previously been described (Fig 1B). In pre-identified tumor specimens, tumor cells were visibly obvious, presenting high intensity of red fluorescence in cytoplasm (CK7). Additionally, LA epithelial cells showed a dramatic enlargement of their cell bodies and nuclei (Fig 1C). LA cell nuclei are as large as cell bodies of normal AT2 cells and, at 63X magnification, display proSPC processes confined to the surface boundary of cell-cell junctions (Fig 1C, sidebar shows side-perspectives of channel 1). Tumor cell processes do not connect to cells classified as AT2, but in rare cases, tumor cell processes did connect directly to neighboring cells of an AT2-like morphology (S4B Video, punctate cells and S5 Video, yellow arrows). Concomitant with the enlargement of tumor nuclei, DNA organization often changes, becoming more spread-out and granular or cavitated appearance relative to DNA staining in stromal neighbors (Fig 1C). CK7 staining reveals cell boundaries of the epithelial cells and hints at a broadened range of cell volumes relative to normal AT2 cells (Fig 1C). Highly elongated stromal nuclei highly reminiscent of smooth muscle layers but of unknown type were also frequently observed (Fig 1D, “S”, and S4B Video, yellow circle).

To determine quantitatively whether these LA epithelial cells and their nuclei had enlarged we had to develop computational strategies for image segmentation. Due to challenges with immunostaining traditional cell boundary markers we ultimately decided to use CK7 stain for epithelial cell body segmentation. However the CK7 staining pattern precluded use of classical watershed approaches. To overcome this hurdle and automate cell body segmentation for hundreds of objects per stack, we trained a UNet-based convolutional neural network with a set of 40 optimized manual cell body annotations (S1 Fig). The resulting spaghetti model is a plot of the network’s confidence in a boundary (Fig 1D, middle, and S1 and S2 Figs), and represents 3D scatter data that can be fit by a surface model using Bitplane Imaris™ software (S3 Fig). Segmentation of AT2 cells from normal tissue was performed in parallel using straightforward thresholding approaches, with a comparable level of accuracy, as assessed by agreement with proSPC or CK7 data (S1D, S1E and S2–S4 Figs). Staining of AT2 cells also revealed thin cellular processes (Fig 1E), discussed later in the manuscript. Segmentation of nuclei was carried out using DNA stain and the cell surface models, correcting for variations in stack brightness (S5 Fig). Due to cell crowding in the tumor, we also manually corrected small clippings to construct an accurate nuclear model (S4 Fig). Notably, nuclear volume segmentation usually required filling cavities present in binary representations of nuclear volumes, highlighting that large regions of oversized tumor cell are DNA-poor (S5 Fig).

Initial 3D surfaces inevitably contained some inaccurate cell models and thus every cell and nucleus was subjected to thorough screening for qualitative agreement with CK7 and DNA data in both 2D and 3D (S3 Fig and Methods). The resulting quality-screened data are provided in S1 Data, tab B., and all quantitative data shown and discussed below are for cells passing this quality assessment screening. In general, the machine learning approach was able to recognize a cell boundary to a similar degree as the authors, and cells failing QC are indicative of poor CK7 staining. Thus, our dataset includes normal lung and LA lung epithelia that the human eye can clearly detect in the microscope and with clear boundaries that stain brightly with our IF protocol. An unfortunate limitation of our data is that it does not include small neoplasms that stain with some proSPC, but not with CK7. An overview of cell models with good cell coverage are shown in S1–S5 Videos; S4B and S5 Videos emphasize that small neoplasms and lesions stain poorly with CK7 and are thus not included in our data, but may be relevant to tumor cell development (green channels shown late in video and S5 Video, yellow arrows).

Quantitation of cell and organelle dimensions in KRAS+ and EGFR+ lung tumors

It is commonly observed that proliferating cells in tumors display a high nucleus:cytoplasm (N:C) volume ratio [13, 14]. However, observations of cell volume dysregulation are less frequently reported. Therefore, we wondered whether reconstructed LA cells, filtered for near-euploid DNA signal, would display only alterations of N:C ratio or whether they might show bona fide increases in cell and nucleus volume (Fig 2A). We found that for both genotypes of LA, epithelial cells had cell volumes and nucleus volume that drastically differed from normal AT2 cells (Kruskal-Wallis and ANOVA, p < 10−4, Fig 2B–2D, S6–S8 Figs). AT2 cell and nuclear volume data with overall mean ± SD of 682.3 ± 194.2 fit to a 2-Gaussian mixture model to recover a first peak of cell volume ± σ of 582 ± 127 fL (n = 802, χ2/df = 1.265 x 10−8) and nuclear volume of 202 ± 34.2 fL (n = 802, χ2/df = 9.285 x 10−8). In contrast epithelial cells across all stages of LAs have mean ± SD cell volumes of 1334 ± 1340 fL (n = 4133), and nuclear volumes of 553.3 ± 378.6 fL (n = 4082). Considering only near-euploid cells, defined as 1.6–4.4n (n = haploid genome), gives cell volumes of 1086 ± 755.6 fL (n = 2683) and nuclear volumes of 462.3 ± 222.2 fL (n = 2671, S6 and S7 Figs). However, inspection of the cell volume distributions and outliers in the data reveals that eliminating cells >4.4n results in elimination of outliers in the long tail >7 pL and loss of the long tail in the distribution (Fig 2B and S6–S8 Figs). Thus, in the absence of ploidies > 4.4n, size dysregulation, defined as standard deviation (S.D.), is 5.9-fold higher for cell volume and 6.5-fold higher for nuclear volume in diseased versus normal (Fig 2C and 2E). Surprisingly, alterations of N:C ratio were much more modest (Fig 2E and S8 Fig) compared to the extent of cell and nucleus size alteration (Fig 2C and 2D). Importantly, polyploidy contributes to size dysregulation by a 77.6% increase in the S.D. of tumor cell volume relative to near-euploid tumor cells (Fig 2F). However, we still observe an 86.6% increase in mean volume of near-euploid tumor cells relative to 2n AT2 wild-type cells. Thus, polyploidy is not necessary to observe a nearly 2-fold cell-size increase in human LA.

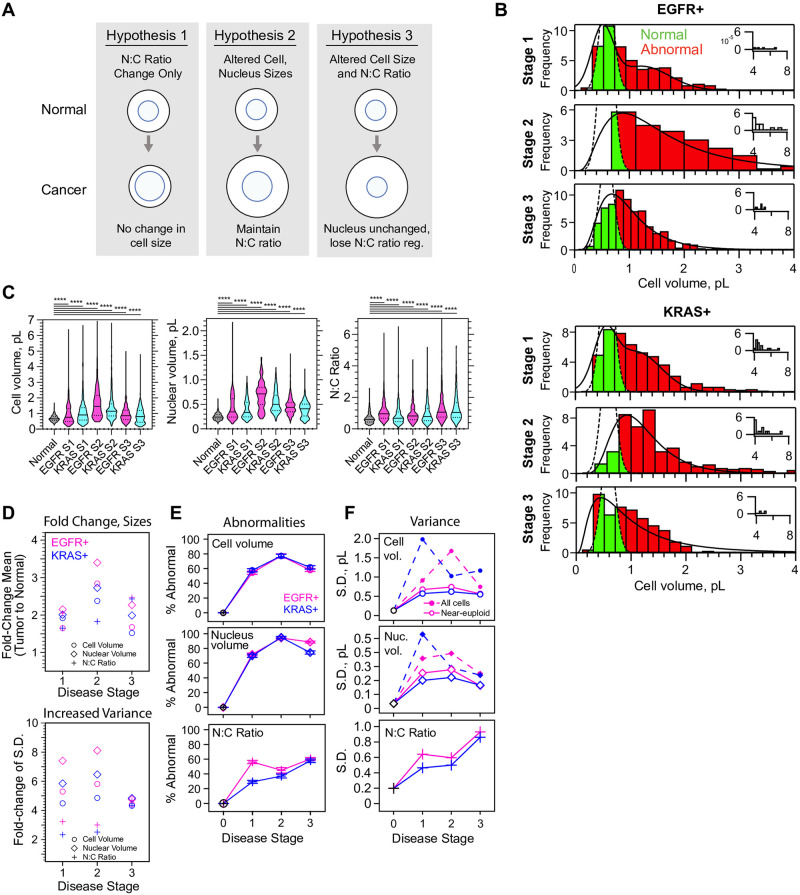

Fig 2. Quantitation of cell and nucleus dimensions in EGFR+ and KRAS+ lung tumors.

A., Schematic: potential outcomes for cell and nucleus scaling in cancerous cells, hypothesis 2 is that LA retains nuclear scaling function. B., histograms of cell volumes of near-euploid (1.6–4.4n) cells (N = 21, n = 2683) as a function of EGFR+ (N = 10, n = 1411) or KRAS+ (N = 11, n = 1260) genotype and stage. Green, cell volumes for tumor cells within the boundaries of the 2n normal AT2 cells; Red, cell volumes outside the Gaussian distribution of 2n population of Normal AT2 cell volumes. C., violin plots for near-euploid cells show very significantly abnormal scaling and significant changes in distributions between stages. 1–2 and 2–3. Colors alternating for visibility, normal in grey. Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, p<1 x 10−4 (****). Select pairwise p-values for Mann-Whitney tests in Tables 1–3. D.-E., quantitation of differences between near-euploid tumor cells and 2n wild-type AT2 cells. Circles, cell volume. Diamonds, nuclear volume. Crosses, N:C ratio. D., Corresponding fold change (tumor-to-normal) for cell sizes (top); standard deviation (bottom). Error bars ≤ 2.7 x 10−3 omitted for clarity Magenta, EGFR+, Blue, KRAS+. E., percentages of cells which fall within the regression fits to histograms for tumor cells, but outside the Gaussian fit to 2n AT2 cells; showing cell volume, nucleus volume and N:C ratio; colored by stage. Error bars, SE. Lines connect points to show trends. F., variance of cell size parameters as a function of stage. Dotted lines and solid markers, ploidy most significantly affects the variance of cell and nuclear volume. Related to Table 4 and S1 Data gives detail.

Table 1. P-value results of pairwise Mann-Whitney testing select conditions shown in Fig 2C, cell volume of near-euploids.

| Normal | EGFR S1 | EGFR S2 | EGFR S3 | KRAS S1 | KRAS S2 | KRAS S3 | |

| Normal | NA | 1 X 10−4 | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM |

| EGFR S1 | NA | NA | NM | NM | 1.2 x 10−3 | NM | NM |

| EGFR S2 | NA | NA | NA | NM | 1 x10-4 | 4 x 10−4 | NM |

| EGFR S3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NM | 1 x 10−4 | 1.5 x 10−3 |

| KRAS S1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NM | NM |

| KRAS S2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NM |

| KRAS S3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Table 2. P-value results of pairwise Mann-Whitney testing select conditions for nuclear volume of near-euploids.

| Normal | EGFR S1 | EGFR S2 | EGFR S3 | KRAS S1 | KRAS S2 | KRAS S3 | |

| Normal | NA | 1 X 10−4 | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM |

| EGFR S1 | NA | NA | NM | NM | 0.2410 | NM | NM |

| EGFR S2 | NA | NA | NA | NM | 1 x10-4 | 1 x 10−4 | NM |

| EGFR S3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NM | 1 x 10−4 | 1 x 10−4 |

| KRAS S1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NM | NM |

| KRAS S2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NM |

| KRAS S3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Table 3. P-value results of pairwise Mann-Whitney testing select conditions for N:C ratios of near-euploids.

| Normal | EGFR S1 | EGFR S2 | EGFR S3 | KRAS S1 | KRAS S2 | KRAS S3 | |

| Normal | NA | 1 X 10−4 | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM |

| EGFR S1 | NA | NA | NM | NM | 1 x10-4 | NM | NM |

| EGFR S2 | NA | NA | NA | NM | 2 x10-4 | 0.3321 | NM |

| EGFR S3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NM | 1 x 10−4 | 0.7944 |

| KRAS S1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NM | NM |

| KRAS S2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NM |

| KRAS S3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Next we asked whether the level of size dysregulation of near-euploid LA cells varied with cancer genotype or disease progression. Therefore we included in our dataset 10 patients pre-identified with either EGFR+ and 11 with KRAS+ genotypes, with 3–4 patients staged 1–3. Collapsing all stages, there is little difference between cell or nuclear volume distributions for EGFR+ and KRAS+ patients (S6 and S7 Figs). However, separating data by stage and genotype reveals subtle differences in the prevalence and trajectories of size dysregulation (Fig 2B and 2C, S9 and S10 Figs). Although we expected cell size dysregulation would worsen with stage, the independent EGFR+ (nnear-euploid = 1411, ntotal = 2194) and KRAS+ (nnear-euploid = 1260, ntotal = 1939) datasets both displayed the highest fraction of cell and nucleus size dysregulation at stage 2 (Fig 2C–2E, S9 and S10 Figs). Somewhat convincingly, both genotypes track together in terms of their trajectories of size dysregulation with stage (Fig 2B–2E). A significant difference between two genotypes occur at stage 1, in which KRAS+ tumor cells displayed more normal nucleocytoplasmic ratios (Fig 2C and 2D), perhaps due to slightly larger cell size and smaller nuclei compared to EGFR+ cells (Fig 2D).

Importantly, size dysregulation is not caused by a small subpopulation of cells in these LAs. Considering near-euploid cancer cells, we calculated the percent of cells whose cell volumes and nucleus volumes extended outside of the first normal AT2 Gaussian (Fig 2E, Table 4 and Methods). We found that 54.5–77.2% of near-euploid cells fall outside the range of normal AT2 cells, suggesting that size dysregulation is highly prevalent in both tumor genotypes. The extent of dysregulation is most dramatic stage 2, in which 95% of all nuclear volumes are abnormal and more than 77% of cell volumes, irrespective of ploidy (Fig 2D, Table 4). The percentage of cells with abnormal cell or nucleus sizes is also largely independent of cell ploidy (Table 4). N:C ratio abnormalities are more modest for near-euploids, although they do increase by stage 3 of LA progression (Fig 2C and 2D, S11 Fig). In EGFR+ the N:C ratio dysregulation occurs earlier than in KRAS+, reaching a plateau at stage 1 (Fig 2D). The increase in N:C ratio observed at stage 3 appears consistent with slight reductions in cell volume but considered across all cells some scaling is evident (S11 Fig). Altogether our data support partial nuclear scaling with cell volume in cancer, and broader general shifts upward in terms of nucleus size and cell size relative to the wild type.

Table 4. Percentages of abnormal cell volumes, nuclear volumes, and N:C ratios vs. stage, genotype, and DNA content.

| Genotype | Stage | Ploidy range | Cell volume | Nuclear volume | N:C ratio | Number of Patients, N | Number of cell models, n (% total)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR+ | 1 | All cells | 55.9 ± 1.7 | 76.4 ± 1.4 | 56.7 ± 1.7 | 4 | 876 |

| EGFR+ | 1 | Near-euploids | 54.5 ± 2.1 | 72.0 ± 1.9 | 56.3 ± 2.1 | 4 | 555 (63.4%) |

| EGFR+ | 2 | All cells | 89.8 ± 1.3 | 97.1 ± 0.7 | 47.0 ± 2.2 | 3 | 514 |

| EGFR+ | 2 | Near-euploids | 77.2 ± 3.0 | 94.2 ± 1.7 | 45.0 ± 3.6 | 3 | 190 (37.0%) |

| EGFR+ | 3 | All cells | 59.0 ± 1.7 | 88.2 ± 1.1 | 61.1 ± 1.7 | 3 | 805 |

| EGFR+ | 3 | Near-euploids | 58.0 ± 1.9 | 88.7 ± 1.2 | 60.4 ± 1.9 | 3 | 666 (82.7%) |

| KRAS+ | 1 | All cells | 65.8 ± 1.8 | 71.1 ± 1.7 | 26.1 ± 1.6 | 4 | 734 |

| KRAS+ | 1 | Near-euploids | 57.7 ± 2.2 | 70.0 ± 2.1 | 29.3 ± 2.0 | 4 | 498 (67.8%) |

| KRAS+ | 2 | All cells | 82.4 ± 1.6 | 95.0 ± 0.9 | 35.4 ± 2.0 | 4 | 572 |

| KRAS+ | 2 | Near-euploids | 77.2 ± 2.3 | 95.0 ± 1.2 | 37.1 ± 2.6 | 4 | 340 (59.4%) |

| KRAS+ | 3 | All cells | 63.0 ± 1.9 | 79.7 ± 1.6 | 55.8 ± 2.0 | 3 | 633 |

| KRAS+ | 3 | Near-euploids | 61.8 ± 2.4 | 74.5 ± 2.1 | 57.8 ± 2.4 | 3 | 422 (66.7%) |

*See also, S1 Data. Standard error of percentages are estimated as the standard error of a proportion. See methods.

Cell and nucleus size dysregulation is not simply explained by altered ploidy, and the extent of dysregulation differs between patients

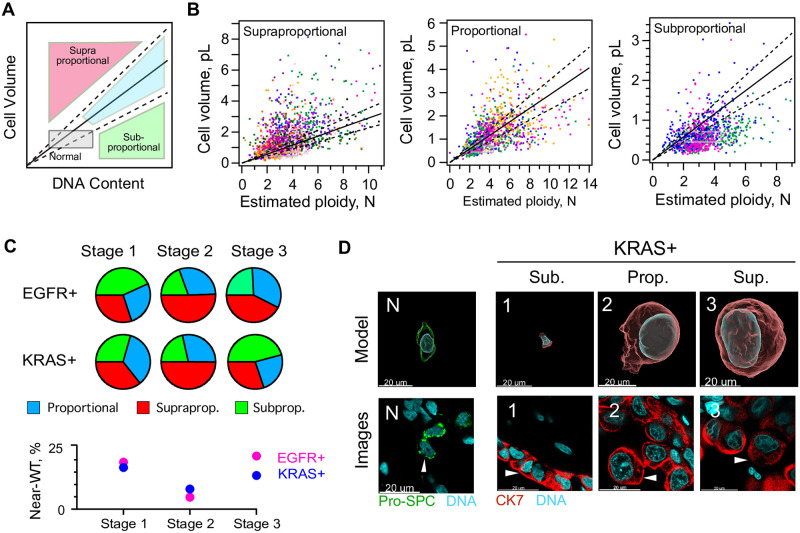

Polyploidy is known to have a general effect on cell volume, and is a feature of aggressive cancers that is proposed to affect drug resistance and recurrence [18, 59–62]. Therefore, we asked to what extent cell and nucleus size dysregulation could be explained by changes in genome content, and whether individual patients showed distinct scaling relationships. For this analysis we plotted the volume of each tumor cell against its ploidy for each patient specimen (S12 and S13 Figs), compared to a prediction line that represents a simple multiplication of the mean DNA and volume of a normal AT2 cell. Patient samples that showed a significant number of abnormal cells above the AT2 prediction for polyploidization were classified as “supraproportional”, meaning higher cell volume enlargement than expected for the ploidy (Fig 3A and 3B, S12 and S13 Figs, see Supplemental Methods for our decision rule). Patient samples containing many cells below the line were classified as “subproportional”, or having smaller cell volumes than expected for polyploid. A majority(52.4%) of patient samples showed nonrandom enrichment of, and a majority of supraproportional cells (Fig 3B and 3C, S1 Data, tab E). Supraproportional cell volume behavior is highest at stage 2 for both genotypes (50.6% of EGFR+ cells, 49.9% of KRAS+ cells, Fig 3C, pie charts) consistent with their being the highest amount of size dysregulation (Fig 2B and 2C). By stage 3 there is increased prevalence of both “proportional” cells–cells with cell volume:ploidy that acts like simple multiplication of AT2 cell volume:ploidy—and “Near-WT” cells, near-euploids classified with cell volume within μWT ± σ = 582 ± 127 ratio (Fig 3A, grey box and Fig 3C, bottom). KRAS+ cells become more subproportional in stage 3, suggesting elevated ploidy without proportionate cell size increases (Fig 3B, top). Examples of supra- and subproportionality are visible in IF (Fig 3D). From these observations we conclude that size dysregulation is common in patients, and that its dependence on ploidy is patient-specific and not predominant.

Fig 3. Ploidy alone cannot explain a majority of cell and nuclear size dysregulation.

63X images shown. A., schematic: subgroups of scaling relationships between DNA content and cell volume: supra: cell volumes larger than expected for ploidy; sub: DNA content higher than expected for cell volume. Colors, individual patient data. Grey box, near-WT, with AT2 volume μ ± σ and near-euploid (n = 1.6–4.4). B., distributions of cell ploidy and volume for individual cells; colored to distinguigh patients. Solid black line indicates simple multiplication of the estimated cell volume and ploidy of a normal AT2 cell, or the equivalent slope; showing +/- 1 S.D., dotted lines. For example, the solid passes through the point (2 x 582 fL, 2 x 2n), where 582 is the mode of the first gaussian fit to the AT2 cell volume distribution (See S6 Fig). The three plots each represent a binning of patients from all stages and both genotypes, but with either no preference, Proportional, or a departure from this line, Subproportional, or Supraproportional. C., top, the fraction of cells classified within each category of abnormal (EGFR+, N = 10, n = 2195, KRAS+, N = 11, n = 1939, S1 Data, tab E). More cells in stage 2 display the supraproportional phenotype, and subproportional cells are enriched in stage 3 KRAS+ cancer. C., bottom, Near-WT, cells with cell volumes close to WT (455–709 fL) that are also near-euploid (1.6–4.4n) are rare in LA, but are depleted in stage 2. Magenta, EGFR+, Blue, KRAS +. D., images of high-quality KRAS+ cell models for each representative category, right, with corresponding 2D images; N, typical AT2 controls. 1, subproportional, 2 proportional, 3 subproportional. White arrows, cells corresponding to models seen in 3D renderings. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Cell-size dysregulation is strongly correlated with loss of tissue organization and local tumor cell density

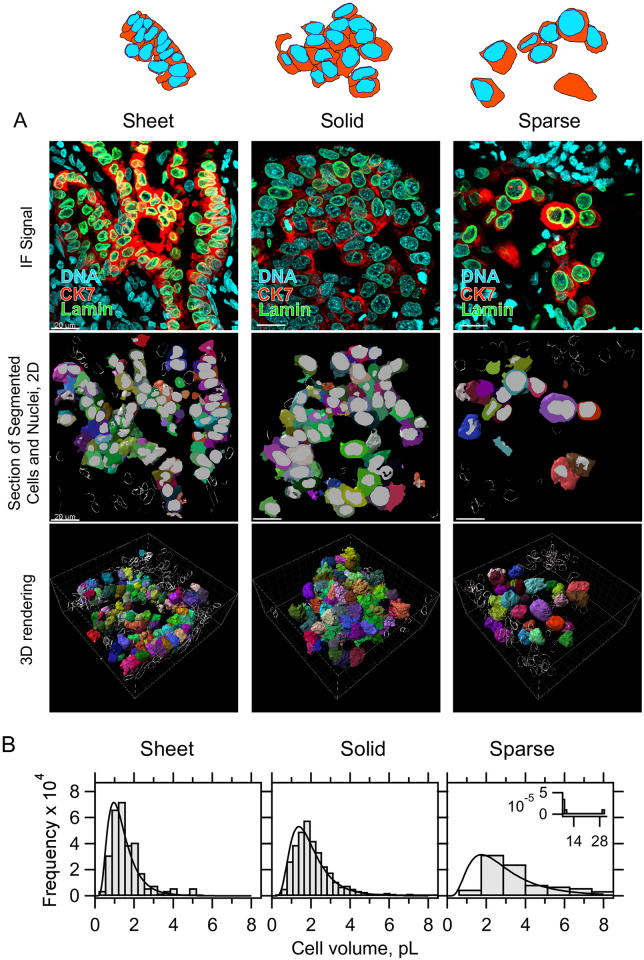

We wondered whether tissue organization within LAs might relate to the phenotype of cell size dysregulation. Gut-like morphologies–sheets of epithelial cells–are not normally found in lung alveoli, but are commonly seen in LAs [42]. Within our three-dimensional image reconstructions of LAs we identified three general categories of tumor tissue organization (Fig 4). A gut-like sheet pattern of cells we refer to “sheet growth” and is present in 61.0% of our image stacks (45/75, Fig 4, left, S1, S4 and S5 Videos, and S1 Data, tab H.). A second pattern of more “solid growth” contained highly packed cells that took on either a cuboidal appearance or one of spheroid tangled cells with elongated tails (46.7%, 35/75 image stacks, Fig 4, middle, and S2 Video). A third pattern of “sparse growth” often neighbored the other two patterns and tended to contain a lower density of cells (8.0%, 6/75 image stacks, Fig 4, right, and S3 Video). Quantification of image stacks from both genotypes predominantly containing each growth type at stage 2, shows that the extent of cell volume dysregulation correlates with tissue pattern type (Fig 4B). Both the mean and breadth of cell volume distributions tracks with tissue organization in the tumor (μSheet = 1430 ± 850, μSolid = 1963 ± 1083, μSparse = 3439 ± 3480, errors SD, Fig 4B and S1 Data tab G.). Cells with sparse organization tend to achieve largest sizes. Additionally, smaller cells tend to be more elongated, consistent with patterns of sheet like growth (S15 Fig). These data suggest that cell size dysregulation may be linked to loss of local tumor organization and cell density.

Fig 4. Tumor tissue organization correlates to the extent of cell size dysregulation.

A, Schematic: sheet, solid, and sparse patterns of tissue organization describe most lung tumor data. Top: representative IF signal for three types, immunostained for CK7 (red) and Lamin A+C (green), observed in both EGFR+ and KRAS+ genotypes, EGFR+ patients shown. middle: Renderings of 2D segmentations; nuclei (gray) and cell surfaces (rainbow), Scale bars, 20 μm. bottom: rendering of 3D segmentations, with stromal controls shown as bubble depictions. White box shows perspective scale, 2 μm per small tick mark. B., cell volume distributions taken from segmented image stacks similar in morphology to the canonical ones shown, exclusively from stage 2 LA and from both genotypes. Sample sizes N patients and n cells, parentheses show respective (EGFR, KRAS) samples: NSheet = 4 (1,3), nsheet = 155 (63,92), NSolid = 4 (2,2), nSolid = 438 (275,163), NSparse = 2 (1,1), nSparse = 73 (22,51).

Human lung tumor cells of near-euploid DNA content can be purified on the basis of cell size

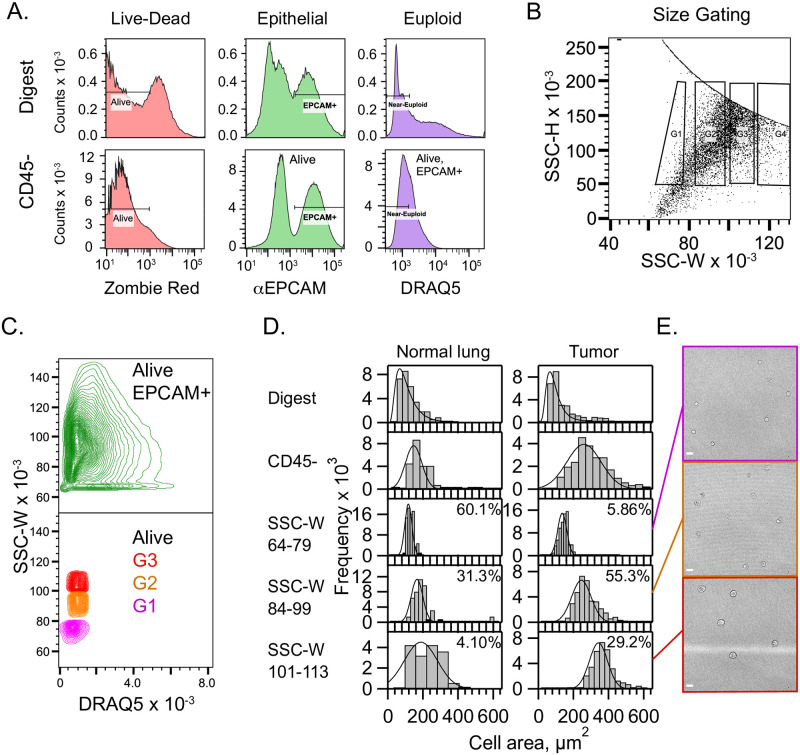

To confirm cell size dysregulation occurs in near-euploid LA and rule out artefacts related to imaging or sample preparation, we decided to isolate cells from resected tumors, select for cells of lower, near-euploid DNA amounts, and sort them by size using flow cytometry. Building on a general framework for separating human cells correlating their dimensions to light scattering profiles [63], we developed a FACS-based strategy for separating near-euploid human LA epithelial cells on the basis of their sizes.

This approach combines three protocols developed previously: a gentle digestion cocktail to preserve CD45 receptors for removing blood cells [64, 65], fixing cells to preserve their shape in the flow cytometer, and quenching fixative with glycine to prevent cell clustering [66]. Our cell suspensions were CD45- after depleting immune cells. Importantly we determined that for epithelial cells from LAs, side-scattering width (SSC-W) parameter was proportional to cell cross-sectional area (ACell = (-159 ± 44) + (4.35 ± 0.48)SSC-W μm2, N = 12, S16 Fig) [63].

To enrich cells of interest we gated for live and dead cells using Zombie Red, epithelial cells using EPCAM, and lower ploidies using the low-DNA DRAQ5- gate (<1.5x mode, Fig 5A). We further separated cells into size bins using SSC-H vs. SSC-W gates as shown (Fig 5B, SSC-W = 64–79, 84–99, 101–113). Reassuringly, cells were in clearly distinct bins of SSC-W but had normal DRAQ5 content (Fig 5C). After sorting, the bins showed clear separation by cell area (Fig 5D). As expected, normal lung tissue displays only modest shifts in size distribution and a small yield of cells in the largest cell-size gate (Fig 5D and S17 Fig). SSC-A vs FSC-A plots show that FSC-A does trend upward with SSC-W gates G1-G3 as expected for objects of increasing cross-section (S18 Fig shows a traditional). These results are consistent with those from whole mount tumor imaging, and further demonstrate the high prevalence of epithelial cell size dysregulation in LA, independent of high ploidy.

Fig 5. Near-euploid tumor cells can be purified and sorted by cell size using flow cytometry.

A. 9.43 x 105 total events shown for a dissociated tumor from patient 5296 of unspecified genotype and grade. Signal gates to purify epithelial cells that were alive when fixed, and with near-euploid DNA amounts are shown left-to-right overlaid on fluorescence histograms for the parent digest, top row, and CD45- MACS flow-through, bottom row. The DNA gate is 1.5x the mode shown for CD45-. B., The SSC-H vs SSC-W plot is gated as shown to separate Zombie Red-/EPCAM+/DNA- cells selected from A. C., Contour plot of the SSC-W as a function of DNA for Zombie Red-/EPCAM+ cells, green, as compared with DNA-size-sorted cells as shown. Size-sorted tumor cells have SSC-W that is essentially independent of DNA amount. D., Representative histograms of cell areas measured from brighfield images of cells on a hemacytometer as shown in E., for normal lung tissue, left, and a LA tumor, right. Top to bottom, each row shows the parent, the MACS CD45- flow-through, and the results from the three size gates. Percentages, relative cell yields for gates G1-G4. G4 always contained low yield aggregates. E., brightfield images of cells sorted by gates G1-G3, and with mean cell areas close to those shown in 5D. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Cell-size dysregulation is AT2-like, and correlated with loss of a novel network of cellular processes

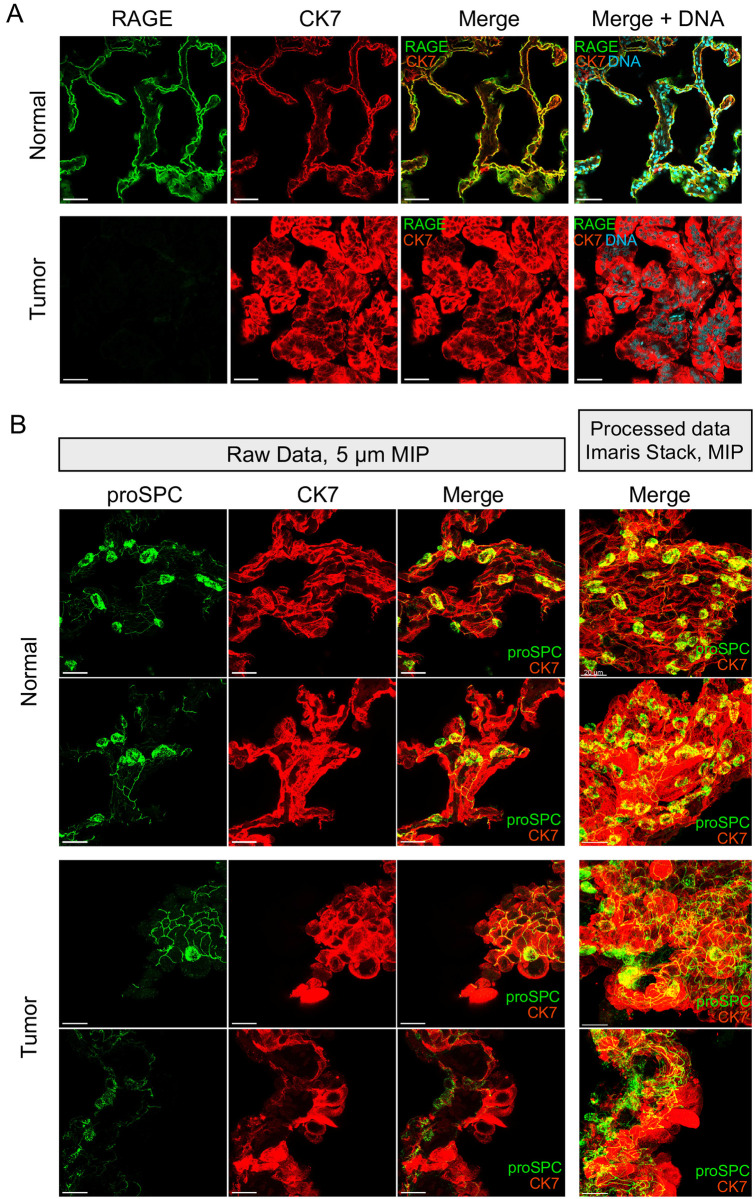

In another attempt to explain cell size dysregulation in LA, and given the observation that sheet-growth cells are smaller and retain size regulation, we considered whether cell size dysregulation in is in any way linked with preexisting pathways for differentiation. AT2 cells differentiate into AT1 cells through a process of flattening coupled to a loss of expression of the AT2-specific marker prosurfactant protein C (proSPC, [45]). As AT1 volumes are unknown, we considered whether cell size dysregulation results from AT1-like differentiation, sans flattening. However, RAGE, a marker specific for AT1 cells in normal tissue showed no signal in LA cells (Fig 6A). In addition, we observed significant flattening of LA cells only rarely (S19 Fig). Thus, our data are not consistent with a model of AT1-like differentiation leading to cell size dysregulation in LA.

Fig 6. AT2-like cells display cellular processes whose organization is altered in lung adenocarcinoma.

A., 25X images at 0.3779 μm resolution showing a single plane display RAGE, (green) is expressed highly in AT1 cells in normal tissue, top, but we could not detect expression in either genotype of tumor cells bottom. KRAS+ shown. Cells immunostained for CK7 (red) and DNA (cyan). B., 63X images shown. Left three columns, raw data shown in a maximum-intensity projection (MIP) 5 μm thick illustrates the behavior of the AT2 process network in normal distant controls, top, and tumor lung, bottom. Right column, a snap from the Imaris workstation of a MIP over an entire processed image stack shows the overall structure of the process network. Each row shows a different specimen (see Table 5). proSPC (green), CK7 (red). Bottom row, transition regions are observed in both genotypes of LA and contain presumptive diseased AT2-like cells that neighbor enlarged CK7-expressing cells. EGFR+ tumors shown (also S4 and S5 Videos).

Table 5. Patient identifiers corresponding to data used to create each image shown and select figures.

| Figure | Patient ID(s) |

|---|---|

| 1A and 1B | 4850 |

| 1C | 4839 |

| 1D | 4843 |

| 1E | 4852 |

| 2,3B and 3C | See Table 7 |

| 3D, left to right | 4843, stack N3, cell 18; 4856, stack T3, cell 34; 4848, stack T2, cell 882; 4850, stack T3, cell 82, |

| 4A (left, middle, right) | 4843, 4840, 3437 |

| 4C | Sheet: 4842T1,4842T3, 4851T2, 4852T4,4853N4 |

| Solid: 4840T1, 4840T2, 4842T2, 4842T5, 4850T4, 4850T5, 4853T3. | |

| Sparse: 4842T4 4850T3 | |

| 5 | 5283,5296,5301 (5296 shown)* |

| 6A | 4852, 4839 RAGE also imaged but not shown |

| 6B (top to bottom) | 4841, 4852, 4837, 4843. |

| 7B | 4848, 4855 (4848 shown) |

| 7D | 4855 |

| 7F | 4855 |

| 7H | Normal, 4852, Voids, 4843 |

| Lamin-associated DNA, 4841, Granular, 4840, wagonwheel, 3437, cytoplasmic inclusions, 4855 | |

| S1 | 4843 |

| S2 | 4843 |

| S3 | 4840 |

| S4 | 4854 |

| S5 (left to right) | 4846, 4840, 4838 |

| S14A | 4854 |

| S16 | 5283,5296,5301,5230,5231,5338,5353,5356,5365,5367,5376,5428 |

| S17 (reading order, also labeled) | 5230, 5231, 5283, 5301, 5296* |

| S18 | 5296* |

| S19 | 4854 |

| S20 | 4855, 5531 (the mouse ID) |

| S21A (by column, left-right) | 4841, 4841, 4837, 4843 |

| S21B | 4854 |

| S22 (reading order) | 4839, 4837, 4848, 4849, 4854, 4839 |

| S23, top to bottom (also labelled) | 4846, 4855, 4846 |

| S24 (N = 8 of each genotype) | 4837, 4838, 4840, 4841, 4842, 4843, 4844, |

| 4845, 4846, 4847, 4851, 4852, 4853, 4854, 4855, 4856 | |

| S30 | 4844 |

| S1 Video | 4843 |

| S2 Video | 4840 |

| S3 Video | 3437 |

| S4 Video | 4843 |

| S5 Video | 4855 |

| S6 Video | 1484* |

| S7 Video | 1484* |

| S8 Video | 1484* |

| S9 Video | 1484* |

| S10 Video | 1484* |

| S11 Video | 1484* |

| S12 Video | 1484* |

| S13 Video | 1484* |

*ID#’s not included in Table 7 were of unspecified genotype or grade.

Next we considered the alternative possibility that LA cells express AT2-specific markers and show morphological changes characteristic of AT2 cells, as suggested by results in mice [44]. Fortuitously, IF revealed a previously unreported feature of human AT2 cell anatomy, along with a corresponding pathology in LA cells (Fig 6B). We refer to these structures as “processes” or “process networks”. Processes are robust to antibody titration and display incomplete colocalization with E-cadherin and CK7 (S20 and S21 Figs). We supposed that if processes are a cross-reaction with extracellular matrix (ECM), they should disappear during a mechanically gentle collagenase/dispase digestion over several hours. However, observations revealed they are clearly not elements of ECM (S6–S12 Videos). During digestion, processes remain wrapped in shafts of intracellular cytokeratin (S11 Video), can remain connected between AT2 neighbors (S8 and S9 Videos), and can even be freed from ECM entirely (S7 and S12 Videos). Although exceedingly fragile, processes loosely follow the paths of CK7 bundles and show a level of complexity not typical of cross-reaction artefacts (S21 Fig, S4A and S4B Video). Amino acids 1–100 of proSPC that were the antigen for our antibody do overlap with the 35-residue region that makes up only 10% of the mass of the secreted form, yet we observe no significant reaction with the inner alveolar walls [48]. We hypothesize that processes are components of the cytoplasm of human AT2 cells. We do caution that a second antibody frequently used in mouse studies, raised against residues 1–32 of human proSPC was less effective in our hands and was not able to detect processes like those shown (S20 Fig and Table 6). Neither antibody we tested detected processes in normal or LA mouse samples. Thus, if mice possess this trait, an antibody raised against the mouse propeptide 1–100, with identity of 86% with the human sequence, may be required to reveal these structures (S20 Fig). In human LA, process-like staining is visible in sheet and solid growth patterns (Figs 1C and 6B, S22 Fig). Sparse CK7-positive cells are usually visible in proximity to sheet and solid regions, where they lack process-like staining (S22 Fig). Conversely, collagenase-resistant clusters of LA cells retain process-like staining at their interior junctions (S13 Video). These results support a link between cell size dysregulation and alterations in surfactant physiology, and strongly suggest human LA cells are AT2-like.

Table 6. Primary and secondary antibodies used in this study.

| Antigen | Host | Clonality/Conjugation | Manufacturer | Catalog number or Name | Application/Fold dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Pulmonary surfactant-associated protein C, propeptide 1–100 (proSPC) | Rabbit | Polyclonal/- | Abcam | ab90716 | 1° IF / 1:200 |

| Human Pulmonary surfactant-associated protein C, propeptide 1–32 (proSPC) | Rabbit | Polyclonal/- | Millipore Sigma | AB3786 | 1° IF / 1:200 |

| Proprietrary synthetic lamin A/C propeptide (Lamin A+C) | Rabbit | Monoclonal/- | Abcam | ab108595 | 1° IF / 1:200 |

| Proprietary synthetic Fibrillarin peptide (Fibrillarin) | Rabbit | Polyclonal/- | Abcam | ab5821 | 1° IF / 1:200 |

| Human SON/DBP5 1463–1598 (SON) | Rabbit | Polyclonal/- | Abcam | ab121759 | 1° IF / 1:200 |

| Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 7 (Cytokeratin 7, CK7) | Mouse | Monoclonal/- | Novus Bio | OV-TL 12/30 | 1° IF / 1:100 |

| Rabbit Gamma Immunogobulin Heavy and Light Chains (IgG) | Goat | Polyclonal/AlexaFluor-488 | Thermo Fisher | A-11034 | 2° IF / 1:500 |

| Mouse Gamma Immunogobulins Heavy and Light Chains (IgG) | Goat | Polyclonal/AlexaFluor 568 | Thermo Fisher | A-11004 | 2° IF / 1:500 |

| Human Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM) | Mouse | Monoclonal/AlexaFluor-488 | BioLegend | 324210 | 1° Flow / 1:50 |

| Proliferation marker protein Ki-67 (Ki-67) | Rabbit | Polyclonal/- | Abcam | Ab15580 | 1° IF / 1:500 |

| Advanced glycosylation end product-specific receptor 39–58 (RAGE) | Rabbit | Monoclonal/- | Abcam | ab37647 | 1° IF / 1:200 |

Significance of dysregulated cell and nucleus sizes to cell and tumor biology

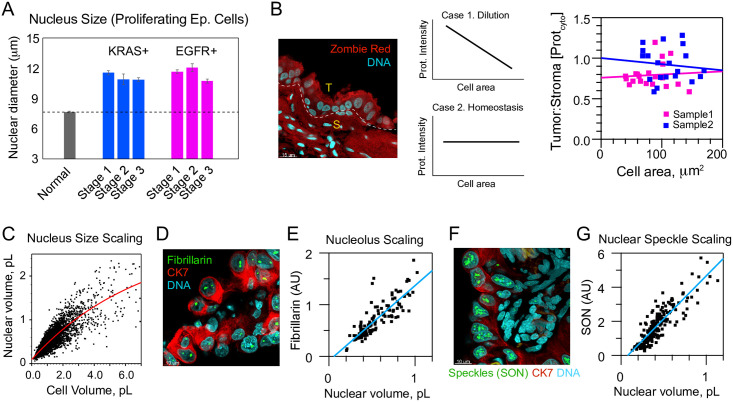

The high prevalence of dysregulated cell sizes in LA suggests that these cells are contributing to tumorigenesis. However, an alternative hypothesis is that these enlarged cells are no longer functional or proliferative and perhaps senescent. To test this, we measured the average nucleus size of proliferating normal and LA cells across genotypes and stages. We found that the average nucleus size of proliferating cells was dramatically increased in LAs (Normal, 7.64 ± 0.04 μm, EGFR, 11.4 ± 0.12 μm, KRAS, 11.1 ± 0.12 μm error SEM, p = 2.5 x 10−69), suggesting that these enlarged cells are not senescent but are contributing to tumor growth (Fig 7A, S23 and S24 Figs).

Fig 7. Enlarged EGFR+ or KRAS+ lung adenocarcinoma cells can proliferate, possess similar protein density to stroma, and display organelle size scaling.

A. Nucleus sizes from proliferating EGFR+ and KRAS+ tumor cells identified by Ki-67 staining, relative to non-proliferative normal AT2 cells (NEGFR = 8, NKRAS = 8, n = 435). B., Zombie Red (red) is a broadly amine-reactive dye that in these FFPE samples reacts equally with small stromal cells, S, as it does with enlarged cancer cells, T, which is inconsistent with cells swelling via water uptake (N = 2). DNA stained with TO-PRO-3 (cyan). Right, Zombie Red intensity of KRAS+ tumors, a proxy for protein density in the cell, does not show the downward trend with cell area expected for water-diluted cells (N = 2, n = 20). C. Allometry of nuclear volume as a function of cell volume for LA (N = 21, n = 2082). Red line, double exponential fit to data. D., Fibrillarin (green) marks nucleoli comparing tumor cells of varying size in a KRAS+ stage 3 patient’s tumor (ID# 4855). CK7 (red), TO-PRO-3 (cyan). E., Total fibrillarin content in nuclei scales with segmented nuclear volume as expected for productive nucleoli (related to D., N = 1, n = 212). F., SON (green) marks nuclear speckles (also KRAS+ patient 4855). CK7 (red), TO-PRO-3 (cyan). G., Quantification of total SON content shows speckles also scale with segmented nuclear volume as they do in living cells (related to G., N = 1, n = 125).

A recent study proposed that water uptake is a consequence of aneuploidy, based on stiffness measurements of culture cells and plots of cell-size vs. ploidy for the NCI-60 panel [30, 31, 67]. To simplify our analysis of swelling, we considered two extreme cases. In the first case, water uptake fully explains cell volume differences predicting a linear negative correlation between protein density in cytoplasm and volume (Fig 7B, Case 1). In the second model, protein density is constant with cell size, implying no dependence (Fig 7B, Case 2). To test these models, we examined both intensities of Zombie Red, which reacts with all lysines, and CK7, a cytoskeletal protein that scales expression with cell volume [22]. The Zombie Red analysis shows that relative intensities in cytoplasm are not dissimilar from smaller, immediately-adjacent stromal cells (Fig 7B, compare S and T), but does not necessarily support either model. CK7 staining also supported neither swelling nor independence, but did suggest the very largest cells rarely possess the upper 50% of possible protein density (8.3% of cells >2 pL, 18.8% of cells ≤ 2 pL, S25 Fig). Rounded bodies and nuclei are another defining characteristic of turgid cells in hypotonic medium [68]. Such morphologies do exist within our samples, but are not conspicuous (e.g., a handful of nuclei in Fig 4A, center and right are representative). Consistent with this interpretation, cell model sphericity was 0.47 ± 7.1 x 10−4, with sphericities of ≥0.6 present in only 0.6% of all measurements (n = 4133, S1 Data, tab B). Similarly, lamin A+C staining of nuclei showed highly irregular surfaces (final portions of S2 Video, Fig 4 and S26 Fig). Nuclear models show a minority of oblate (15.0%) or prolate (26.0%), ellipticities less than 0.3. Overall, our data supports a view in which a minority of LA cells swell, but in a manner that is not proportional to cell size.

For enlarged cells to function and proliferate, they would need to expand their organelles and output of pathways for RNA production and ribosome biogenesis. We first noticed that enlarged cells properly maintained nucleus size scaling (Fig 7C). To determine whether nucleolus size and rRNA processing might be upregulated, we stained LA samples for fibrillarin. Indeed, we found a clear size scaling trend in which nucleolus size was increased in epithelial cells with enlarged nuclei (Fig 7D and 7E). To determine whether splicing and RNA production might also be upregulated in enlarged cells we stained for SON, a splicing marker that localizes to nuclear speckles [69, 70]. These nuclear bodies also showed a clear size scaling trend with nucleus size (Fig 7F and 7G). Together these data indicate that enlarged LA cells minimally maintain their protein and organelle homeostasis, scaling it as a function of cell size. These results contradict the notion that these enlarged cells are only swollen or senescent and hints at their higher functional output.

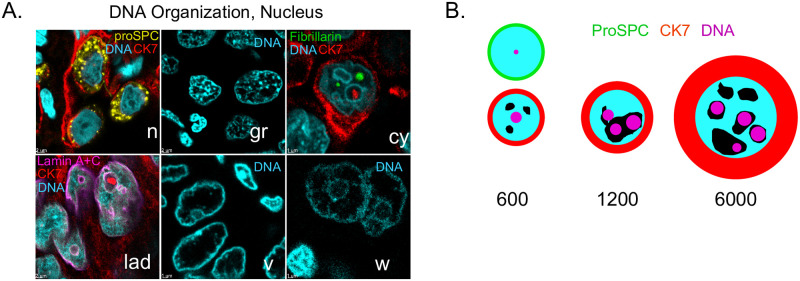

Genomes of oversized lung adenocarcinoma cells are physically expanded

Given the correlations observed between cell and nuclear volume, and findings that changes in chromatin organization can be observed in cancer, we asked whether DNA staining displayed any special patterns in LA nuclei. We observe five common classes of DNA staining, and mixtures of these that describe most DNA data in LA (Fig 8A). Normal AT2 cells have mostly even DNA-staining profiles, with little granularity, and are so consistent that neoplasms are usually conspicuous. In LA, the most common pattern consists of a granular appearance suggestive of local heterochromatic regions. Cytoplasmic inclusions are ringed by concentrations of DNA at their boundary. Lamin-associated DNA is concentrated at the nuclear periphery and sometimes at the periphery of inclusions. DNA voids consist of large volumes that stain poorly for DNA, but are otherwise not significantly bordered. “Wagon-wheel” arrangements are reminiscent of nucleoli, but may not contain them, as suggested by weak DNA staining at their central “hub” regions.

Fig 8. Diversity of nuclear organization and a revised 2D perspective of human lung adenocarcionoma.

A., typical patterns of DNA staining observed in both EGFR+ and KRAS+ LA. n, normal AT2 cells with proSPC (yellow), CK7 (red), DNA (cyan). gr, granular DNA. cy, cytoplasmic inclusions, with fibrillarin (green). lad, lamin associated DNA, with Lamin A+C (magenta). v, DNA voids. w, “wagon-wheel” DNA. Idealized representations of nuclear structures shown for clarity. See Table 5 for associated patient ID information. B., Visual depiction of the relative equatorial cross-sectional area in μm2 of typical LA cells, if they were spheres, relative to the nucleus (cyan). green, AT2, cyan, DNA, black, DNA voids, magenta, nucleoli/speckles.

We took particular note of Lamin association and thus we asked whether nuclear size dysregulation is correlated in any way with Lamin A+C wrinkling. We observe high Lamin A+C expression in all our patient samples, as has been observed previously for the LA subtype [71]. Lamin A+C is such a strong marker that it enabled segmentation of most of our dataset with the membrane detection algorithm of Imaris™. This algorithm creates objects that are significantly smaller than the nuclear volume, but contains very accurate shape information about the sphericity, i.e., wrinkling, of the nuclear envelope (S26 and S27 Figs). We reject any significant relationship between lamin wrinkling and nuclear volume, and by proxy cell volume (S28 Fig). However, Lamin A+C data support a similar trend as nuclear volume data with disease stage as measured by DNA thresholding, supporting that method (Fig 2D).

The presence of DNA-poor voids led us to ask whether genomes could be diluted in larger cells. To test this, we plotted the cell volume as a function of the ratio of ploidy:nuclear volume, where the latter tracks the amount of genome dilution (S14B Fig), showing that DNA in large LA cells >2 pL is diluted within the nucleus, consistent with voids.

Taken together with the above, and with the observations of lamin-associated DNA, we wondered if DNA movement to the envelope, sometimes associated with gene regulation, may be a hallmark of oversized cells [72]. To answer this question, we used the distance transform to create eroded shells of nuclei for four patients, found the amount of DNA within 1.5 μm of the nuclear surface, and then calculated the amount of nuclear-envelope enrichment of DNA as a function of cell volume. However, there is no trend with cell size, but shell-packing of DNA staining may be a signature of individual patients (S29 Fig).

Fig 8B summarizes how this study has revised our expectations about the 2-dimensional length scales of cell bodies, nuclei, nucleoli, and nuclear voids of AT2 or LA cells of different sizes, if cells and nuclei were actually perfect spheres.

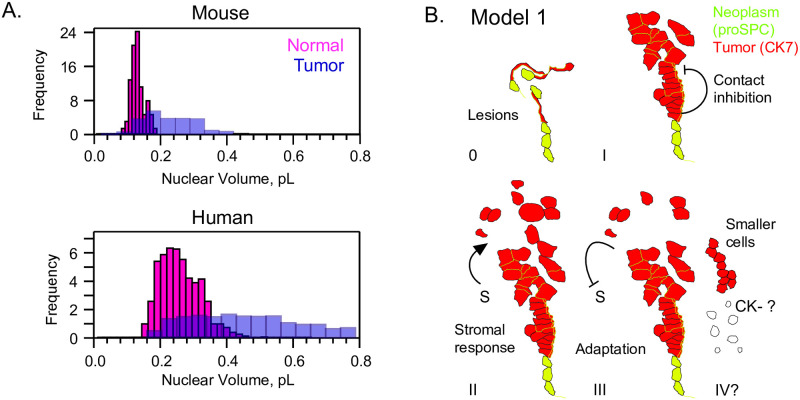

Conservation of size dysregulation in a mouse model lung cancer system

We were curious whether the phenomenon of cell and nucleus size regulation might be specific to human LA or might also be found in a mouse model of lung cancer. We segmented normal nuclei and also cancer nuclei from proSPC-staining cells in a KrasLSL-G12D/+; p53fl/fl; Rosa26LSL-eYFP/LSL-eYFP mouse. Our analysis showed that although mouse AT2 cells are smaller than human AT2 cells, both show loss of size homeostasis in cancer (Fig 9A). Mean nuclear volume for the mouse was 117.4 ± 21.36 (n = 58), 1.72-fold smaller than the first Gaussian of human AT2s. For tumor cells, which were filled with proSPC at all sizes, the nuclear volume was 254.7 ± 358.5 (n = 207), or 2.17-fold smaller than the overall human LA mean. Importantly, the mouse coefficient of variation for LA nuclear volume was 1.41, somewhat higher than the human average for all LA cells of 0.68. Altogether, the human model possesses a greater range of nuclear volumes and is more relevant to human disease, whereas the prevalence of volume variation in the mouse model provide opportunities for genetic characterization of pathways of size variation.

Fig 9. Epithelial cell-size dysregulation is also found in mouse tumors and may proceed with loss of tissue organization and upregulation of transcription.

A., KrasLSL-G12D/+; p53fl/fl; Rosa26LSL-eYFP/LSL-eYFP mouse lung tissue shows nuclear size dysregulation, despite volumes of ~50% that of humans. B., Model 1: Oncogenesis is characterized by lesions, loss of flattening to an AT1 form and thus shortening of processes. At stage I, a contact-dependent mechanism preserves some cell size regulation. Stage II involves more mixed stroma/tumor regions and disorganization, leading to sparse cells and increased cell size dysregulation. Late stage (III-IV) cancers are dominated by adaptation towards maximal cell division rate, evolution of immune resistance, and also loss of cytokeratin staining. Smaller cells, and those of the more subproportional volume:ploidy relationship in KRAS+ cancers (Fig 3) may become enriched in late stages.

Discussion

Our survey of authentic human tumors has underscored to us the limits of reductionist models in understanding a complex multicellular community. Clearly much is to be learned from in situ studies in 3D such as the one presented here [24, 25, 53]. Our findings are particularly relevant to recent discussions related to oncogenesis, giant superpolyploid cells (GSPPCs), and osmotic homeostasis [30, 44, 59, 73].

Although the oncogenic event that leads to LA is unknown, Lin et al. established in mice that AT2 cells can generate new tumors [44]. Our observations of proSPC staining support this association between AT2 cells and LA cells in humans. Others have suggested that the oncogenic event involves tetraploidy specifically [59]. Although we suspect this is true in some cases, our plots of cell-volume vs ploidy show that most cells are well within 2-4n range of DNA amount. Thus, if tetraploidy is the first oncogenic event then in our patients there must exist later events that enrich for lower DNA contents.

GSPPC’s are observed after cancer cell lines are subjected to chemotherapeutic drugs and ionizing radiation, and display persistent dormancy followed by a restart of division and even budding of multiple daughter cells [73]. This behavior supports a model wherein GSPPC’s cause recurrence of disease after treatment leads to remission. Our data do not rule out such a model, but show GSPPC’s are exceedingly rare observables in untreated LA patients (compare Fig 2B and S7 Fig and see Table 4). An upper limit for their prevalence could be estimated from Table 4, and cannot exceed 10% of abnormal cells in stage 2 EGFR. Thus, future estimates of the prevalence of GSPPC’s in treated patients may provide a more complete picture of the relevance of this phenomenon to disease.

Osmotic imbalance in cancer was not supported by our simple Zombie Red test or CK7 staining variation, or by nuclear rounding of Lamin (Fig 7H and S27 Fig). Thus, the model proposed by Tsai et al. that water uptake is increased in aneuploid cells could not explain our data as it could the data for yeast. Our own careful review of the Dolfi et al. data did not find a significant dependence of volume on odd ploidy number across the diverse NCI-60 panel [30]. The only trend we could find between aneuploidy and cell swelling in human LA was a depletion in CK7 staining in the very largest cells (S25, red box). Our data does not conflict with an assumption of nuclear stiffening of cancer cells however, if such stiffening can be explained by protein production, nuclear dilution, or RNA production (Fig 7B–7G).

Our 3D segmentation approach overcomes the general limitations of uniform 2D sampling, and is representative of a growing trend in which AI, combined with human expertise, can be leveraged to overcome methodological hurdles. We acknowledge that the resulting cell models are an approximation, and yet they provide an unprecedented level of detail with respect to measuring scaling changes of diseased cancer cells. Indeed, we observe slightly larger volumes for nuclei than can be estimated from nuclear areas reported by Nakazato et al. from paraffin blocks, which range from 242–508 fL. Taking the midpoint of that range to be 375 fL, and the midpoint of our range of nuclear mean volumes to be 650 for polyploid nuclei suggests the 2D approach underestimates the volume by the significant value of ~2-fold [17].

Our method required fixation and clearing for IF, so the volumes we report are smaller than those of live lung cells and their nuclei. Shrinkage artefact caused by neutral buffered formalin fixative is fairly small in an aqueous medium, ~3% for strips of rat kidney [54]. On the other hand, benzyl alcohol:benzyl benzoate (BABB) is reported to shrink tissue sections ~50%, with less data available for individual cells [74]. Exactly accounting for this shrinkage would have required live patient cells paired with each of our FFPE specimens. Yet size distributions of fixed tumor cells in aqueous buffer show similar size-change and size-distribution behavior as cells in BABB, suggesting, shrinkage affects large and small cells and nuclei to approximately the same extent (Fig 5D). In terms of staining, our approach was technically limited with regard to the use of the CK7 marker, and thus more work is required to characterize the scaling changes of cells that undergo loss of CK7 expression.

From the clinical perspective, KRAS+ patients displayed a lower N:C ratio at early stages (Fig 2D, bottom). Thus, careful cytometric statistics may be required for early KRAS+ cancers. Our data on individual patients’ cell volume-ploidy profiles support the important conclusion that observations of cell-size variation are not sufficient to conclude high ploidy overall. Our shell analysis of envelope packing also shows that patients that have DNA voids may fall into a distinct class (Fig 8A and S29 Fig).

Most importantly, our results using both microscopy and flow cytometry have shown that the influence of DNA amount on cell-size dysregulation and cell-size increase in LA is greatly overemphasized (Fig 2). A century ago and more, Levine and his contemporaries established the paradigm that “giant” cancer cells are of high ploidy, and raised the question whether such cells contributed to disease or were “amitotic”, i.e, irrelevant to disease [75]. To address these long-standing concerns, our study found that the size-ploidy paradigm holds for cells of volume 7–30 pL which are exclusively of the polyploid variety, but that the majority of LA cells are abnormally large, irrespective of ploidy (Table 4). These oversized cancer cells represent the vast majority of tumor cells throughout all stages, a situation sufficient to imply that they contribute to LA progression.

Cell enlargement is a consequence of cell growth, which takes place up until the start of cell division. Therefore, the enrichment of abnormal cells that is specific to stage 2 LA (Fig 2B) likely reflects changes in cell cycle length [4, 6, 76, 77]. Pauses in the cell cycle do occur during dormancy, one cause of which is proposed to be immune response [78]. In this context, it is therefore interesting to note that B cells and macrophages that may be competent to engage tumor cells are specifically enriched at stage 2 [79]. We hypothesize that stage 2 engagement of non-cancerous cells may lengthen the cell cycle for tumor cells, explaining some of the enlargement of near-euploid cells that is special to that stage.

Our analysis of proliferation using the Ki-67 marker established the existence of proliferating oversized cancer cells, but clearly, there exist many cells that are oversized but do not stain with Ki-67 (S23 Fig). These cells may be arrested in G0, and if so, whether or not they remain so may be relevant to some forms of chemotherapy resistance.

It remains an open question what pathways lead to giant near-euploid cells in LA. Some have proposed that increased volume supports additional glycolytic machinery as a consequence of the Warburg effect [80]. Some LA cells switch to a mucinous form, but these phenootypes were absent from our data [81]. However, our data support the idea that giant lung adenocarconima cells retain some aspects of a secretion genetic programme. We hypothesize that giant LA cells inappropriately overexpress factors related to secretion, in the absence of a delivery system for multilamellar bodies. More recently, it has also been proposed that p38 and Cdk regulate cell size, and that retinoblastoma may control a cell size set point. In addition, future work may clarify whether G1 length alteration contributes to the cell size enlargement observed in the LA cells characterized in this work [82–84].

Our new flow cytometry method for sorting tumor cells by size offers many new opportunities for studying such oversized cells and cell size dysregulation in disease. The method may be attempted with any epithelial cancer, if the SSC-W parameter is robust across cell types. We stress that our success with the method was a direct consequence of recommendations of Tzur et al. [63].

Cell density or packing appears to be a necessary condition for cell size regulation in LA. Combined with the observation that proSPC staining and processes are lost at cell boundaries, this strongly suggests loss of multicellularity in LA is sufficient for loss of epithelial determination. One might envision that our “shedding” and sparse size-dysregulated LA cells may be enriched with pioneers for escape to the nearby blood (S4 Video). It has also been observed that cells which lose rigidity sensing can become transformed and overgrow [85].

Although our study set out to study cell size, we were fortunate enough to discover networks of AT2 processes. These structures have likely gone unnoticed due to the specific markers required, their extreme fragility, and their requirement for an intact alveolus. A thorough search of the literature suggests that processes may have been observed, but were misidentified as part of other structures. In particular, Weibel refers to a ridge at the boundary of the AT1 cell body in a scanning electron micrograph, and clearly labels it part of AT1 cells [47]. However, our digests showed these structures can be biochemically isolated from AT1 cells and ECM, but remain attached to and linked between AT2 cell bodies, even as part of a CK7-staining structure (S10 and S11 Videos). We find no evidence that processes that surround AT1 cells terminate, although smaller “subprocesses” do so. We hypothesize that process networks work like a system of pipes to distribute surfactant over the alveoli of larger mammals, a model that has implications for any disease that involves surfactant. Their networking also suggests the possibility of intercellular communication. Perturbations of this network could have profound effects on normal lung function. Chronic diseases with variable amounts of scarring over time would likely interfere with and even destroy these networks of processes. Although further investigation of AT2 processes was beyond our initial scope, we suggest worthy future directions include study of living, intact AT2 networks by careful tracking of mature surfactant protein C, as well as examination of these structures in the context of other diseases [48].

While scaling of organelles with cell size in nature is well-established, our data has contributed to a perspective that cancer cells can possess scaling, albeit a type of scaling which is offset from that of normal cells. For LA cells, nuclei are swollen with nucleoplasm, and their nucleoli are aberrant in shape and number but otherwise scale appropriately with volume as do wild-type cells (Fig 7C, and S28 Fig shows an enlarged version).

Considering all our observations, we propose Model 1, which invokes a contact-inhibition mechanism–loss of contacts between cells may contribute to cell size dysregulation (Fig 9B). Before stage 1 in humans, cell size dysregulation is still mostly limited by contact inhibition and AT2-like differentiation. This intrinsic cell-size variation is not size dysregulation, but comprises ranges of cell size consistent with growth and division and remains as a component of all stages. By stage 1 in humans, loss of differentiation and organization leads to a population of solid and sparse cells with disrupted contact inhibition. In the absence of cell-cell contact, cells fully de-differentiate, reorganize their chromatin, and activate genes appropriate for a solitary life, as observed in loss of heterotypic contact-induced inhibition of locomotion, or the mesenchymal-to-amoeboid transition [86, 87]. Stage 2 cells are larger because immune responses are still competent and thus contribute to mixed presentation of stroma and consequently additional production of solitary cells. By stage 3, evolutionary adaptation results in cells that both compartmentalize to sheets and also divide at the maximal rate, producing the minimum degree of cytoplasm. If they are even smaller, from Fig 4B we could speculate that the end-point for stage 4 or in the most aggressive cancers may be mostly smaller sheet-like cells (Figs 4B and 9B, IV) [42]. It is an open question what the cell-size variation is in mesenchymal-like cells that do not express CK7.

We have shown that the near-euploid fraction of human and mouse LA are useful models for studying the molecular underpinnings of cell size dysregulation and variation. In combination with new flow cytometry tools we have suggested, these models provide a convenient means to study the genetic basis of cell-size regulation in mammals.

Methods

Patient samples, genotyping, formaldehyde fixation and paraffin embedding

Formaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples were kindly provided by the University of Pennsylvania Tumor Tissue and Specimen BioBank (TTAB). Samples included ten blocks from untreated patients genotyped as EGFR-positive/KRAS-negative and eleven blocks from patients genotyped as KRAS-positive/EGFR-negative. Staging was determined by standard measurements of tumor diameter and interpretation of H&E by a pathologist and were as indicated in Table 7.

Table 7. Stage, genotype, and pathological classification of lung adenocarcinoma patients.

| Patient ID | Genotype | Stage |

|---|---|---|

| 3437 | EGFR+/KRAS- | IA |

| 4838 | EGFR+/KRAS- | 1A |

| 4837 | EGFR+/KRAS- | 1B |

| 4839 | EGFR+/KRAS- | 1B |

| 4842 | EGFR+/KRAS- | 2A |

| 4840 | EGFR+/KRAS- | 2B |

| 4841 | EGFR+/KRAS- | 2B |

| 4843 | EGFR+/KRAS- | 3A |

| 4844 | EGFR+/KRAS- | 3A |

| 4845 | EGFR+/KRAS- | 3A |

| 4848 | KRAS+/EGFR- | 1A |

| 4849 | KRAS+/EGFR- | 1A |

| 4846 | KRAS+/EGFR- | 1B |

| 4847 | KRAS+/EGFR- | 1B |

| 4850 | KRAS+/EGFR- | 2B |

| 4851 | KRAS+/EGFR- | 2B |

| 4852 | KRAS+/EGFR- | 2B |

| 4853 | KRAS+/EGFR- | 2B |

| 4854 | KRAS+/EGFR- | 3A |

| 4855 | KRAS+/EGFR- | 3A |

| 4856 | KRAS+/EGFR- | 3B |

Fixation was performed in neutral buffered 10% formalin for a minimum of six hours, with all steps including stepwise dehydration, clearing with xylenes and paraffin-embedding performed on a commercial tissue processor. Processing was performed by the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Division of Anatomic Pathology.

Normal distant control tissue was identified and marked by Dr. Feldman by inspection of H&E clinical slides. FFPE blocks were then subdivided, such that distant control regions were used for imaging normal AT2 cells.

Dewaxing and sectioning

Up to 12 FFPE blocks, including 6 distant controls and 6 tumor specimens, were dewaxed for 24–72 hours in two six-well aluminum Reacti-blocks (Fisher, TS18811) immersed in 3 L of xylenes (Fisher Chemical, X3S-4). Samples were next washed once with 50% ethanol and then twice in anhydrous ethanol for storage at -20°C. Storage was for up to two months for principal IF in which channel 1 was proSPC, Lamin AC, Fibrillarin, or SON, up to six months for Ki-67 proliferation testing. S30 Fig shows that IF was stable over the period of principal imaging for both normal controls patient 4844, with 25X images shown in Fig 7B and S6K Fig representative of sample response after 6 months storage. For whole-mount sectioning, specimens were rehydrated to 50% ethanol for 5 minutes with nutation followed by one wash with water and one wash with PBS. Human specimens were sectioned to 150–200 μm on a Leica Vibratome (VT1000S) in PBS, mounted with superglue but otherwise with no solid or gelatinous infusion such as agarose, with maximum amplitude settings and frequency of from 50–100% depending on tissue softness. i.e., 100% normal lung distant controls required the highest setting. After sectioning, specimens were again dehydrated for storage at -20°C.

Antigen recovery, immunofluorescence, clearing and mounting

All staged and genotyped tumor FFPE blocks were kindly provided by the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Cancer Center Tumor and Biospecimen BioBank (TTAB). FFPE sections stored in ethanol at -20°C were rehydrated as described. Antigen recovery upon 150 μm sections was performed in loosely capped 5 mL reaction vials using a Decloaking Chamber (BioCare Medical) at 110° for 37 minutes using a 10X TE buffer at pH 9 at a 1:100 dilution in dI water (Dako Target Retrieval). The sample was allowed to cool to room temperature and then washed 3 times with 0.5X SSC buffer (Corning). Samples were transferred to bleaching buffer (0.5X SSC, 2% hydrogen peroxide, 5% formamide) and bleached for at least 4 hours under a 130 V 100 W bulb at a distance of 20 cm at 4°C. Samples were returned to RT, then washed three times in quick succession and again every hour for four hours with PBT (PBS plus 0.1% triton and 2 mg/mL BSA). Blocking was performed for 2 hours at RT in blocking reagent with nutation. Blocking reagent was a 9:1 mixture of PBS containing 0.1% triton X-100 and no BSA and goat serum (abcam 7481). We stress that any BSA in blocking reagent specifically interfered with IF in our hands. Primary antibodies at the concentrations listed in Table 6 were applied in blocking reagent overnight in 2 mL glass reaction vials with nutation at 4°C. On the second day, samples were washed with PBT at room temperature on a rotator over a 7-hour period with the wash changed at least three times at intervals of at least 1 hour. Secondary antibodies as shown in Table 6 were applied overnight in the dark at 4°C in blocking reagent with nutation. On day three, the samples were again washed on a rotator for 7 hours in PBT. TO-PRO-3 at a 1:500 dilution in PBS was applied in one wash for 20 minutes on a rotator and then refreshed for 10 minutes such that a faded blue color remained in the solution, which we took as indication that DNA binding sites were saturated. To prevent washout of TO-PRO-3 stain that we have observed in mixtures of water/methanol, samples were immediately dehydrated to 100% methanol for 30 minutes with nutation, then washed again once with methanol and once with anhydrous methanol at intervals of 30 minutes. To clear tissue, samples were placed in 1:2 Benzyl Alcohol:Benzyl Benzoate (BABB) on a rotator in the dark for 10 minutes. Next the initial BABB was replaced, and samples were cleared overnight in a dark drawer. The next day the BABB was exchanged and the samples were cleared for another 24 hours. BABB was refreshed a final time at mounting. For mounting, samples were subdivided 1–3 times with a razor to lay flat, then placed in custom laser-cut chambers with 3.75 x 19 x 19 mm windows filled with BABB. Samples were pressed under a second 18 x 18 mm coverslip to lay flat before the chambers were filled to level. 40 μL of BABB was removed to leave a small bubble and ensure no overflow before the chamber was finally sealed with nail polish.

Laser-scanning confocal imaging

Principal imaging relevant to all cell volume segmentation and high-resolution figures was performed at room temperature on a Zeiss LSM-880 with a Plan-apochromat 63X/1.4 oil DIC M27 objective with 0.19 mm free working distance, 0.17 mm coverglass thickness, 25 mm FOV, and 45.06 parfocal length. Scanning settings were 10 (fastest setting), with 900 x 900 pixels and 0.15 μm3 voxels, employing a 1X digital zoom. Laser lines were 488, 561, and 633 nm, employing transmittances of 5, 1, and 1% respectively, and each used a gain setting of 600.

Efforts were made to minimize sampling bias during imaging, but only regions staining brightly with either proSPC, for normal AT2 cells or mouse tumor cells, or CK7 (bonafide tumor cells) were imaged. To capture representative morphological patterns, a number of 25 X images were snapped to capture all the overall morphological variation present in a sample. This initial impression was used as a guide to gather from 1–4 scans at 63X until all the bright-staining representative morphologies available were captured. Any 63X image stack was constrained to include a minimum of 20 stromal nuclei controls for DNA amount. Therefore, cells with phenotypes which stain weakly with either proSPC or CK7 are not included in our data.

25X images were collected similarly to 63X images, except that the voxel size was 0.3779 μm3 and z-step of either 2 (Ki-67) or 0.5 μm (others).

Attenuation correction and background subtraction of raw data