Abstract

Inactivation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phpA, encoding a putative leucine aminopeptidase, results in increased transcription of algD. The homologous protein in Escherichia coli, PepA, is multifunctional, possessing independent aminopeptidase and DNA-binding activities. Here we provide in vitro evidence that PhpA is an aminopeptidase and show that this activity is the relevant property with regard to algD expression. This regulation occurred at the previously mapped algD transcription initiation site and was not due to activation of an alternative promoter.

Once established in the cystic fibrosis (CF) lung, Pseudomonas aeruginosa persists until relentless inflammatory processes and ensuing tissue damage result in respiratory failure. During this period of chronic infection, dramatic changes take place in the nature of P. aeruginosa. The most striking alteration is the assumption of a highly mucoid phenotype that results from the synthesis of a polysaccharide called alginate (8). The genetic control of alginate expression has been extensively investigated (8). Many regulatory proteins are required for maximal expression of the alginate biosynthetic operon, including AlgB, AlgR, AlgZ, and AlgT (also referred to as AlgU or ς22 [2, 8, 19]). The response regulator AlgB shows no direct interaction with the promoter region of algD, the first gene of the alginate biosynthetic operon. However, algB mutants of mucoid cystic fibrosis isolates are nonmucoid and demonstrate a significant reduction in algD transcription. This led us to postulate the existence of an AlgB-regulated gene encoding a product that directly affects transcription of algD. As algR, algZ, and algT expression is unaffected in an algB mutant (2, 19; S. Woolwine and D. J. Wozniak, unpublished data); these regulatory genes do not likely represent the proposed intermediate in the algB-algD pathway. In a prior study, transposon mutagenesis was employed to identify extragenic suppressors of the algB nonmucoid phenotype (18). The mucoid phenotype of one of the transposon mutants was accompanied by a significant increase in algD transcription (18). The transposon insertion in this strain disrupted a previously uncharacterized gene homologous to pepA, encoding the leucine aminopeptidase of Escherichia coli (18). PepA also is required for the Xer-mediated site-specific recombination at the cer site of plasmid ColE1 (14). We referred to this new gene as phpA (P. aeruginosa homologue of pepA). Our studies with P. aeruginosa PhpA as well as the recent observation that pepA is required for mediating pH regulation of virulence genes in Vibrio cholerae (3) suggest that the PepA family of proteins may also function in controlling pathogenesis. In the present study we extend our investigation by demonstrating a bestatin-sensitive aminopeptidase activity for PhpA and show that it is the loss of this activity which increases algD expression. This regulation was not due to activation of an alternative algD promoter.

The phpA mutant exhibits increased transcription from the previously mapped algD promoter.

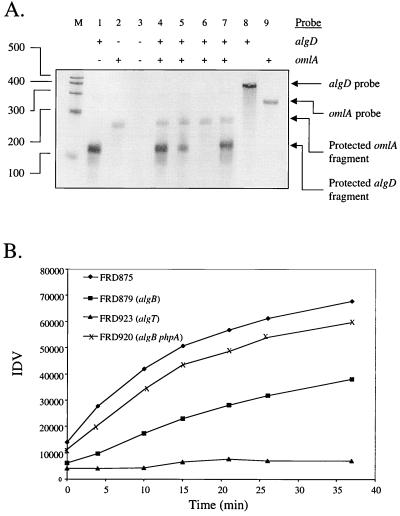

Prior studies revealed that disruption of phpA results in an increase in algD transcription and the conversion of an algB mutant from a nonmucoid to a mucoid phenotype (18). It was unclear if this was due to activation of a novel algD promoter or if the phpA-mediated control was exerted at the previously studied algD promoter (7, 19). To distinguish this, the algD transcription initiation site was examined by RNase protection assay. A digoxigenin-labeled riboprobe spanning nucleotides −174 to +110 relative to the previously described algD transcription start site was synthesized (7, 19) and used to detect algD transcripts in total RNA isolated from the phpA mutant and other relevant strains. In addition, a labeled antisense probe to the omlA transcript was included in the assay. This gene encodes an outer membrane lipoprotein, and its expression has been found to be invariant with regard to growth conditions and serves as an internal standard to verify consistency in technique and integrity of the RNA sample (12). RNase protection assays were performed with 50 μg of total RNA and digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes to mRNA for algD and omlA (internal standard). Riboprobes were synthesized using the Maxiscript T7 in vitro transcription system (Ambion, Austin, Tex.) with pSW218 (omlA) or pSW221 (algD) as the template. For labeled riboprobes, the 0.5 mM UTP present in the transcription reaction was replaced with a mixture of 0.3 mM UTP and 0.2 mM digoxigenin-11 UTP (Roche). RNase protection assays were performed using an RPA III kit (Ambion). Protected fragments were resolved by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electroblotted to nylon membranes. The protected fragments were then visualized by immunodetection with antidigoxigenin Fab fragments conjugated to alkaline phosphatase and the chromogenic substrate nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

Figure 1A demonstrates that all detectable algD transcription in the phpA mutant FRD920 (lane 7) originates from the same promoter as in the parental algB strain FRD879 (lane 5). This also corresponds to the transcription start site utilized in the algB+ strain FRD875 (lane 4). The size of the protected probe fragment is consistent with the predicted size (110 nucleotides) based on the previously mapped algD promoter (7, 19). Consistent with other reports (8, 19), the algD transcript is not detectable in an algT mutant background such as FRD923 (lane 6). In addition to mapping the 5′ end of the algD transcript in the phpA mutant, these data also demonstrate an increase in the amount of algD transcription in this strain compared to the parental algB strain (compare lanes 5 and 7). Figure 1B depicts the increase in the integrated density values for each algD signal during the course of the immunodetection. It is readily apparent that the phpA mutant has significantly more algD transcription than the parental algB strain and that this control is exerted at the prior characterized algD promoter.

FIG. 1.

The phpA mutant utilizes the same algD transcription start site as the parental strain. (A) RNase protection assay for algD transcription. Nucleotide values for RNA markers are indicated to the left. Identities of RNA species are indicated to the right. Use of the algD and/or omlA probes in each lane is indicated at the top. Lanes contain the following RNA samples: M, Century RNA markers (Ambion); lanes 1 to 4, FRD875 (mucA22 algD::xylE [18]); 5, FRD879 (mucA22 algD::xylE algB::Tn501 [18]); 6, FRD923 (mucA22 algD::xylE algT::Tn501, generated by gene replacement of algD in FRD440 [19] with algD::xylE from pDJW530 [18]); 7, FRD920 (mucA22 algD::xylE algB::Tn501 phpA::Tn5-B50 [18]); 8, yeast RNA, no RNase; 9, yeast RNA, no RNase. Total RNA was isolated from P. aeruginosa strains grown in LBNS (18) as described elsewhere (16). (B) The individual bands corresponding to the algD transcripts from each lane in panel A were scanned every 5 min (Hewlett Packard ScanJet Hp scanner) during the color development phase of the immunodetection. The image files were analyzed using AlphaEase version 4.0 (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, Calif.), and the integrated density value (IDV) of the algD band from each strain was plotted versus time.

P. aeruginosa PhpA has aminopeptidase activity.

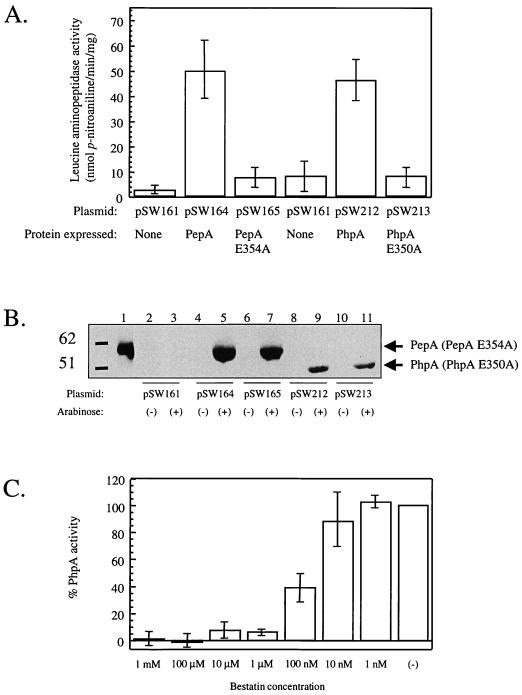

In our previous study, we suggested that PhpA was a functional homologue of E. coli PepA (18). This suggestion was based on (i) the extensive sequence homology (56% identity at the amino acid level), (ii) the presence of seven residues in particular which are believed to be part of the active site and are absolutely conserved among the members of this family of aminopeptidases, and (iii) the fact that the E. coli genomic organization of pepA, holC, and valS, in that order, is reflected in the P. aeruginosa chromosome (15). To confirm that PhpA is an aminopeptidase, we sought to demonstrate such activity in vitro in extracts of E. coli DS957 (pepA) expressing PhpA in response to arabinose induction. For this purpose, we constructed a series of plasmids based on pEX100T (13) which would serve as both arabinose-inducible expression vectors in E. coli as well as gene replacement vehicles allowing cloned genes under control of PBAD to be integrated into the algB locus of P. aeruginosa. All plasmids used in this experiment were derived from pSW161, which was constructed by cloning a 2,185-bp ScaI-ClaI fragment (araC, PBAD, multiple cloning site, and rrnB T1T2 transcription terminators) derived from PBAD30 (9) into pUS68 (10). Plasmids pSW164 and pSW165 were constructed by cloning a 1.9-kb HindIII fragment from pCS126 (PepA [14]) or pRM40 (PepA E354A [11]) into pSW161. Plasmids pSW212 (PhpA) and pSW213 (PhpA E350A) were constructed by cloning 1.7-kb HinfI-HindIII fragments from pSW176 and pSW177, respectively, into pSW161. To generate the phpAI allele encoding PhpA E350A (pSW177), oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis was performed on phpA, using pSW176 (wild-type phpA in pALTER-1 [18]) and the mutagenic oligonucleotide SW20 (5′ CAACACCGACGCTGCAGGGCGCCTGGTG 3′; underscored bases are altered from wild type) with the Altered Sites II in vitro mutagenesis system (Promega). pSW177 was sequenced to verify the phpA1 mutation. These base changes result in a Glu→Ala change at amino acid residue 350 (18), which corresponds to the PepA E354A mutation designed by McCulloch et al. (11).

E. coli DS957 harboring various constructs or vector controls was cultured in Luria-Bertani medium (10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, and 10 g of NaCl per liter) containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5, and cultures were left untreated or induced with arabinose (0.5% [wt/vol]). Incubation was continued for 2 h, after which 25 ml of culture was pelleted, resuspended in 5 ml of TK buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 8.2], 100 mM KCl, 1 mM magnesium acetate, 0.5 mM MnCl2). Cell extracts were prepared by passing the suspension through a French pressure cell (15,000 lb/in2) and removing cell debris by centrifugation. PepA and PepA E354A were partially purified by techniques described elsewhere (5, 11) with the exception of the KCl precipitation step. PhpA and PhpA E350A were prepared from supernatants following a 50% (NH4)2SO4 precipitation of proteins in the clarified extracts to remove residual aminopeptidases and an additional (NH4)2SO4 precipitation of the supernatant [70% final (NH4)2SO4] to precipitate PhpA and PhpA E350A. Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid BCA protein assay (Pierce); 25 μg of protein in 990 μl of TK buffer was equilibrated for 15 min in a 1-cm2 cuvette at 37°C, at which time 10 μl of 100 mM l-leucine p-nitroanilide (prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide) was added. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C, and the release of p-nitroaniline was monitored at 400 nm. Activity was calculated from the molar extinction coefficient of p-nitroaniline (ɛ400 = 1.55 × 104 M−1 cm−1). The results of three independent experiments are shown in Fig. 2A. The results clearly indicate that expression of either E. coli PepA (pSW164) or P. aeruginosa PhpA (pSW212) resulted in a significant increase in the aminopeptidase activity compared to the identically prepared vector control samples (pSW161).

FIG. 2.

(A) Leucine aminopeptidase activities of PepA and PhpA. Cultures of E. coli DS957 (recF laclqZΔM15, pepA::Tn5 [11]) harboring the indicated plasmids were grown and harvested, cytoplasmic extracts were prepared, and PepA or PhpA was partially purified (see text). Twenty-five micrograms of protein was used in each assay. Aminopeptidase activity on the chromogenic substrate l-leucine p-nitroanilide was determined by observing the increase in absorbance at 400 nm. The averages from three independent experiments are represented. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean. (B) Immunoblot analysis of DS957 cells harboring a pepA or phpA plasmid. Lanes 2 to 11 contain extracts prepared as described in the text from DS597 cells with the following plasmids: lanes 2 and 3, pSW161 (vector); lanes 4 and 5, pSW164 (PepA); lanes 6 and 7, pSW165 (PepA E354A); lanes 8 and 9, pSW212 (PhpA); lanes 10 and 11, pSW213 (PhpA E350A). Even-numbered lanes contain extracts from noninduced cells, whereas the odd-numbered lanes are derived from cells induced with arabinose. Lane 1 contains purified PepA (1 μg). The positions of PepA and PhpA (or the corresponding mutants) are indicated on the right. Numbers at the left indicate positions of molecular size standards in kilodaltons. For detection, 100 μg of protein was separated on a 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate–12% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane using a Trans-Blot SD semidry transfer cell (Bio-Rad). After blocking for 1 h with 10% skim milk in 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.6)–137 mM NaCl–0.1% Tween, immunoblot detection was performed with the ECL Western blotting analysis system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Primary antibody (rabbit polyclonal anti-PepA, the generous gift from S. Colloms) was used at a 1:5,000 dilution; the secondary antibody was used at 1:8,000. (C) Bestatin inhibition of PhpA aminopeptidase activity. Twenty-five-microgram aliquots of PhpA prepared as for panel A were preincubated in the indicated concentrations of bestatin (Sigma) for 30 min, and residual aminopeptidase activity was determined as for panel A. Data are depicted as a percentage of the untreated sample of PhpA [(−)], which was set at 100%. The means and error bars represent standard deviations of three independent experiments.

E. coli PepA is a multifunctional protein, possessing both aminopeptidase and DNA-binding activities. The DNA-binding activity of PepA is required for its role in the Xer-mediated site-specific recombination system used by plasmid ColE1 for resolving plasmid multimers. A Glu→Ala change at residue 354 in the active site of PepA abolishes aminopeptidase activity without affecting its function in the Xer system (11). Consequently, there is no detectable aminopeptidase activity over baseline in preparations of DS957/pSW165 expressing PepA E354A (Fig. 2A). A corresponding amino acid substitution in PhpA, E350A, also abolishes aminopeptidase activity. Ammonium sulfate-enriched preparations from DS957/pSW213, expressing PhpA E350A, show no significant aminopeptidase activity (Fig. 2A). The absence of aminopeptidase activity in preparations of DS957/pSW165 and DS957/pSW213 is not due to lack of expression, as immunoblot analysis with polyclonal antiserum raised against PepA demonstrated similar levels of expression of wild-type PepA and PepA E354A as well as wild-type PhpA and PhpA E350A (Fig. 2B).

Loss of PhpA aminopeptidase activity results in an increase in algD transcription.

We sought to determine if PhpA aminopeptidase activity was required for the effect on algD transcription. Bestatin [(2S,3R)-(3-amino-2-hydroxy-4-phenylbutanoyl)-l-leucine] is a transition-state analog of the dipeptide substrate PheLeu and is a competitive inhibitor of many aminopeptidases (17). We tested whether bestatin could produce the same increase in algD transcription in the algB strain FRD879 as the inactivation of phpA in the isogenic strain FRD920. Bestatin has been observed to have an in vivo effect in E. coli when present in the culture at concentrations as low as 10 μM (1). We cultured FRD879 (algB::Tn501 algD::xylE) in LBNS medium (10 g of tryptone and 5 g of yeast extract per liter) in the presence of up to 1 mM bestatin with no demonstrable effect on algD expression (data not shown). This raised the possibility that PhpA was insensitive to bestatin. To test this, ammonium sulfate-enriched preparations of PhpA (see above) were preincubated with various concentrations of bestatin and tested for residual aminopeptidase activity. The in vitro results shown in Fig. 2C demonstrate that PhpA is clearly sensitive to bestatin, as 60 nM bestatin was capable of inhibiting 50% of the PhpA aminopeptidase activity.

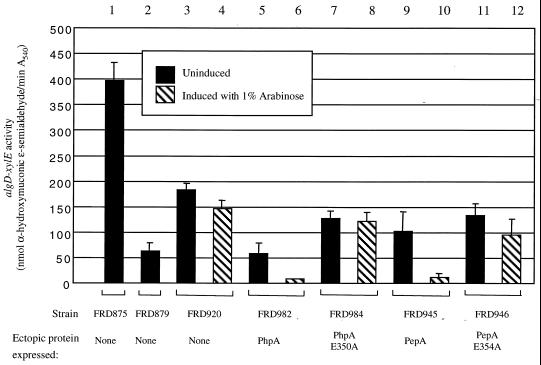

The absence of an in vivo effect of bestatin on algD transcription could be explained by failure of the inhibitor to penetrate the cell, or the inhibitor could be rapidly inactivated or effluxed out of the cell. Alternatively, the effect of PhpA on algD may be independent of the aminopeptidase activity. This possibility must be considered in light of what is known about E. coli PepA. As mentioned previously, PepA is required as an accessory DNA-binding factor in the Xer-mediated site-specific recombination at the cer site of plasmid ColE1 (14). In addition, PepA binds upstream and represses transcription of its own gene, pepA, and of the carAB operon (4, 5). Neither of these PepA functions requires the aminopeptidase activity (5, 11). Therefore, it is possible that PhpA also possesses aminopeptidase-independent functions that may include regulation of algD transcription. To address this, we used allelic exchange with pSW212 and pSW213 to place either wild-type phpA or phpA1 at the algB locus in the algB::Tn501 phpA::Tn5-B50 algD::xylE strain FRD920. The resulting strains, FRD982 and FRD984, express wild-type PhpA and PhpA E350A, respectively, in response to arabinose. XylE activity was used to determine the level of algD transcription in these strains as well as the reference strains FRD875 (algB+), FRD879 (algB::Tn501), and FRD920 (algB::Tn501 phpA::Tn5-B50); the results are shown in Fig. 3. Inactivation of algB (FRD879) results in an eightfold decrease in algD expression compared to the parental algB+ strain FRD875. However, inactivation of phpA (FRD920) partially restores algD transcription, resulting in a significant increase in algD-xylE activity (compare samples 1 to 4). This increase in algD transcription is sufficient to confer a mucoid phenotype in the corresponding algD+ strain (18). Significantly, expression of algD was reversed when wild-type PhpA but not PhpA E350A was expressed (samples 5 to 8). Therefore, phpA1 is unable to complement the effect of phpA::Tn5-B50 on algD transcription. This provides strong genetic evidence that the aminopeptidase activity of PhpA is responsible for the inhibitory effect on algD expression.

FIG. 3.

Loss of PhpA aminopeptidase activity results in increased algD transcription. Allelic exchange (13, 18) was used to replace the algB::Tn501 allele of FRD879 with the phpA, phpA1, or wild-type or mutant pepA allele, all under control of the PBAD promoter, using plasmids pSW212, pSW213, pSW164, and pSW165, respectively. Strains and ectopic proteins expressed at the algB locus are indicated. The strains tested were FRD875, FRD879, and FRD920 (see legends to Fig. 1 and 2), FRD982 (mucA22 algB::pBAD-phpA phpA::Tn5-B50 algD::xylE aacCl), FRD984 (mucA22 algB::pBAD-phpA1 phpA::Tn5-B50 algD::xylE aacCl), FRD945 (mucA22 algB::pBAD-pepA phpA::Tn5-B50 algD::xylE aacCl), and FRD946 (mucA22 algB::pBAD-pepA [E354A] phpA::Tn5-B50 algD::xylE aacCl). The level of algD transcription in these strains was measured as previously described (18) by the XylE activity produced from the algD::xylE transcription fusion. The averages from three independent experiments are represented. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. Activity was calculated from the molar extinction coefficient of the reaction product, α-hydroxymuconic ɛ-semialdehyde (ɛ375 = 4.4 × 104 M−1 cm−1).

One caveat to the interpretation of these results is the assumption that the PhpA E350A mutation only abolishes the aminopeptidase activity and does not disrupt the overall structure of the protein or interfere with any other function. The E350A substitution was chosen because it corresponds to the substitution in PepA E354A. To validate the interpretation of the phpA results, we used the pepA alleles to perform complementation of phpA::Tn5-B50. Allelic exchange was used to place pepA alleles encoding either wild-type PepA or PepA E354A at the algB locus of FRD920. Induction of PepA in strain FRD945 produced a pronounced decrease in algD expression (Fig. 3, samples 9 and 10), whereas expression of PepA E354A in strain FRD946 failed to decrease algD expression (samples 11 and 12). As was the case for expression in E. coli DS957, PhpA, PhpA E350A, PepA, and PepA E354A were expressed in P. aeruginosa to the same degree, as demonstrated by immunoblot analysis (data not shown). These data support the hypothesis that the loss of PhpA aminopeptidase activity is responsible for increased algD transcription.

In this study, we demonstrate the aminopeptidase activity of PhpA in vitro and show that the loss of this activity in an algB mutant correlates with an increase in algD transcription. The tightly controlled PBAD promoter (9) was used to demonstrate that expression of either wild-type phpA or E. coli pepA complemented the phpA mutant, while alleles encoding an aminopeptidase-deficient protein (PepA E354A or PhpA E350A) failed to complement. PepA E354A serves as an important control in this experiment. It has been shown that PepA E354A is still functional in Xer-mediated site-specific recombination (11), and so it is unlikely that failure of PepA E354A to complement the phpA mutation results from protein misfolding due to the amino acid substitution. Thus, aminopeptidase activity is the relevant function of PhpA as far as alginate expression is concerned.

The work presented here raises some interesting questions. For example, how does the physiological defect in the phpA strain result in transcriptional activation of algD? As the bulk nutrient of the culture medium used in our investigations consists of peptides, one might assume that phpA mutants are less efficient at utilizing the medium and this might be relayed to algD expression. Indeed, the phpA strain does exhibit a growth defect, with a doubling time in LBNS of 90 min, compared to 60 min for the parental algB strain (data not shown). This suggested that a deficiency of one or more amino acids might be a stimulus for increased alginate expression. However, supplementing the medium with free amino acids (2 mM) did not have a significant effect on algD expression (data not shown). Another plausible explanation for the effect of the loss of PhpA aminopeptidase activity on alginate expression deals with turnover of endogenous protein. Misfolded or aggregated proteins have been shown to induce the extracytoplasmic stress response (6). This response is mediated, in part, by the ECF family of sigma factors, of which P. aeruginosa AlgT is a member (8). If the phpA strain is defective in hydrolyzing peptides that have arisen due to degradation of misfolded, senescent, or aggregated proteins, this may lead to an increase in AlgT activity and subsequent increases in algD expression. These possibilities are under investigation.

Acknowledgments

Public Health Service grants AI-35177 and HL-58334 (D.J.W.) supported this work.

We thank H. Schweizer for pEX100T, pX1918G, and pX1918GT, which served as the basis for our allelic exchange and transcriptional fusion technology. We are grateful to S. Colloms for providing pCS126, pRM40, purified PepA, and polyclonal anti-PepA antibody. Much gratitude is extended to S. Ma for PBAD30, which was used in the construction of the arabinose-inducible expression vectors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atherton F R, Hall M J, Hassall C H, Holmes S W, Lambert R W, Lloyd W J, Nisbet L J, Ringrose P S, Westmacott D. Antibacterial properties of alafosfalin combined with cephalexin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;20:470–476. doi: 10.1128/aac.20.4.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baynham P J, Wozniak D J. Identification and characterization of AlgZ, and AlgT-dependent DNA binding protein required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa algD transcription. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:97–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behari J, Stagon L, Calderwood S B. pepA, a gene mediating pH regulation of virulence genes in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:178–188. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.178-188.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charlier D, Gigot D, Huysveld N, Roovers M, Piérard A, Glansdorff N. Pyrimidine regulation of the Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium carAB operons: CarP and integration host factor (IHF) modulate the methylation status of a GATC site present in the control region. J Mol Biol. 1995;250:383–391. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlier D, Hassanzadeh G, Kholti A, Gigot D, Piérard A, Glansdorff N. carP, involved in pyrimidine regulation of the Escherichia coli carbamoylphosphate synthetase operon encodes a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein identical to XerB and PepA, also required for resolution of ColE1 multimers. J Mol Biol. 1995;250:392–406. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly L, De Las Penas A, Alba B M, Gross C A. The response to extracytoplasmic stress in Escherichia coli is controlled by partially overlapping pathways. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2012–2021. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.15.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deretic V, Gill J F, Chakrabarty A M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis: nucleotide sequence and transcriptional regulation of the algD gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;11:4567–4581. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.11.4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Govan J R W, Deretic V. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:539–574. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.539-574.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzman L M, Belin D, Carson M J, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma S, Selvaraj U, Ohman D E, Quarless R, Hassett D J, Wozniak D J. Phosphorylation-independent activity of the response regulators AlgB and AlgR in promoting alginate biosynthesis in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:956–968. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.956-968.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCulloch R, Burke M E, Sherratt D J. Peptidase activity of Escherichia coli aminopeptidase A is not required for its role in Xer site-specific recombination. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:241–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ochsner U A, Vasil A I, Johnson Z, Vasil M L. Pseudomonas aeruginosa fur overlaps with a gene encoding a novel outer membrane lipoprotein, OmlA. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1099–1109. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1099-1109.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schweizer H P, Hoang T T. An improved system for gene replacement and xylE fusion analysis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1995;158:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00055-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stirling C J, Colloms S D, Collins J F, Szatmari G, Sherratt D J. xerB, an Escherichia coli gene required for plasmid ColE1 site-specific recombination, is identical to pepA, encoding aminopeptidase A, a protein with substantial similarity to bovine lens leucine aminopeptidase. EMBO J. 1989;8:1623–1627. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stover C K, Pham X Q, Erwin A L, Mizoguchi S D, Warrener P, Hickey M J, Brinkman F S L, Hufnagle W O, Kowalik D J, Lagrou M, Garber R L, Goltry L, Tolentino E, Westbrock-Wadman S, Yuan Y, Brody L L, Coulter S N, Folger K R, Kas A, Larbig K, Lim R, Smith K, Spencer D, Wong G K-S, Wu Z, Paulsenk I T, Reizer J, Saier M H, Hancock R E W, Lory S, Olson M V. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature. 2000;406:959–964. doi: 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Summers W C. A simple method for extraction of RNA from E. coli utilizing diethylpyrocarbonate. Anal Biochem. 1970;33:459–463. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor A. Aminopeptidases: structure and function. FASEB J. 1993;7:290–298. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.2.8440407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woolwine S, Wozniak D J. Identification of an Escherichia coli pepA homolog and its involvement in suppression of the algB phenotype in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:107–116. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.107-116.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wozniak D J, Ohman D E. Transcriptional analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa genes algR, algB, and algD reveals a hierarchy of alginate gene expression which is modulated by algT. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6007–6014. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6007-6014.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]