Heart failure (HF) is an important cardiovascular disease because of its increasing prevalence, significant morbidity, high mortality, and rapidly expanding health care cost.1),2) In 2015, sacubitril/valsartan (S/V, LCZ696) was approved in the United States and Europe as a first in class drug for patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) based on PARADIGM-HF trial.3) In Korea, S/V was approved by Korean Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2016 and then began to be reimbursed from October 2017. However, the eligibility or usage of S/V in Korea has not been well known.

In this issue of the journal, Oh et al.4) reported that among the Korean hospitalized HFrEF patients, 80% met Korean FDA label criteria, while only 12% met the inclusion criteria of PARADIGM-HF trial.3) Compared with ESC-EORP-HFA HF-LT registry5) and PRADADIGM-HF trial,3) the patients enrolled in the Korea Acute Heart Failure (KorAHF) registry6) were more likely to be women, showed higher proportion of diabetes, had lower body mass index and lower systolic blood pressure (SBP). Though there is a limitation that the KorAHF registry enrolled hospitalized acute HF syndrome patients, not chronic stable HF outpatients, making direct comparison with ESC-EORP-HFA HF-LT or PARADIGM-HF difficult, it is the first and largest study to show the S/V eligibility in Asian HFrEF patients.

The eligibility for S/V in the same population could be changed depending on the variety of conditions. Swedish Heart Failure Registry revealed that between 34% and 76% of symptomatic HFrEF patients are eligible for S/V. This wide range of eligibility depends on the background dose of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi)/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).7) SBP and renal function could be varied as well in the course of HFrEF patient care. Therefore, real world eligibility of S/V might be difficult to define and be varied depending on the condition of each patient. Rather, underutilization of S/V in definitely eligible patient could be a significant problem in real clinical practice. There might be several reasons for the underutilization of S/V including patients' and physicians' low awareness of HF and high medical cost of the drug. More importantly physician's clinical inertia8),9) could be one of the main reasons for the underutilization of S/V in eligible HFrEF patients.

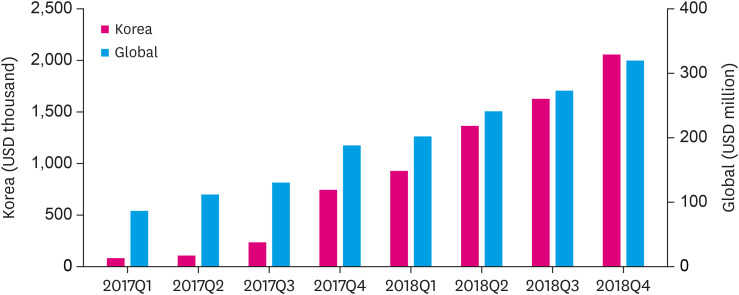

Some physicians ask, “Do I have to switch to S/V if my patient is stable on an ACEi or ARB?” PARADIGM-HF trial3) was not about switching, it was about adding a new class of drug. Moreover, the terminology ‘stable’ can be misleading especially in patients with HFrEF. HFrEF patients with mild symptoms are not stable and progress rapidly, even on guideline directed medical treatment. Over 11% patients per year in the control group in PARADIGM-HF exhibited some manifestation of worsening. Even higher proportions of patients experienced deterioration in symptoms or quality of life.10) In a third (33%) of patients, the first manifestation of progression or worsening is cardiovascular death, mainly sudden cardiac death and S/V was superior to enalapril in reducing both sudden cardiac deaths and deaths from worsening HF.11) Therefore, for eligible HFrEF patients, we need to make more efforts to start at least low dose of S/V and monitor them in a carefully, considered manner. Regarding the real world usage of S/V, there are numerous issues including off-label use, underdosing, titration protocols, etc. However, sales market data revealed the usage of S/V itself have increased rapidly in 2017–2018 worldwide and Korea as shown in Figure 1.12),13)

Figure 1. Quarterly sacubitril/valsartan sales trends worldwide and Korea.

Q = quarter.

Finally, our patients are the ultimate reasons for our interest in S/V and they provided all the necessary information of S/V in both randomized clinical trial and real world registry. Additional collaborative efforts among physicians, health care systems and the manufacturer need to be directed to improve the care of our HFrEF patients.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2018R1C1B6005448).

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

- Conceptualization: Youn JC.

- Data curation: Youn JC.

- Formal analysis: Kim JJ, Youn JC.

- Funding acquisition: Youn JC.

- Project administration: Kim JJ, Youn JC.

- Resources: Youn JC.

- Supervision: Youn JC.

- Visualization: Youn JC.

- Writing - original draft: Kim JJ, Youn JC.

- Writing - review & editing: Kim JJ, Youn JC.

References

- 1.Choi HM, Park MS, Youn JC. Update on heart failure management and future directions. Korean J Intern Med. 2019;34:11–43. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youn JC, Han S, Ryu KH. Temporal trends of hospitalized patients with heart failure in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2017;47:16–24. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2016.0429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:993–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh J, Lee CJ, Park JJ, et al. Real world eligibility for sacubitril/valsartan in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients in Korea: data from the Korean Acute Heart Failure (KorAHF) registry. Int J Heart Fail. 2019;1:57–68. doi: 10.36628/ijhf.2019.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapelios CJ, Lainscak M, Savarese G, et al. Sacubitril/valsartan eligibility and outcomes in the ESC-EORP-HFA Heart Failure Long-Term Registry: bridging between European Medicines Agency/Food and Drug Administration label, the PARADIGM-HF trial, ESC guidelines, and real world. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019 doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SE, Lee HY, Cho HJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of acute heart failure in Korea: results from the Korean Acute Heart Failure Registry (KorAHF) Korean Circ J. 2017;47:341–353. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2016.0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson J, Benson L, Jhund PS, Dahlström U, McMurray JJ, Lund LH. “Real world” eligibility for sacubitril/valsartan in unselected heart failure patients: data from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2019;33:315–322. doi: 10.1007/s10557-019-06873-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavoie KL, Rash JA, Campbell TS. Changing provider behavior in the context of chronic disease management: focus on clinical inertia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;57:263–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-104952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarcho J. PIONEERing the in-hospital initiation of sacubitril-valsartan. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:590–591. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1900139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Packer M, McMurray JJ, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition compared with enalapril on the risk of clinical progression in surviving patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2015;131:54–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai AS, McMurray JJ, Packer M, et al. Effect of the angiotensin-receptor-neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 compared with enalapril on mode of death in heart failure patients. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1990–1997. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novartis. Novartis quarterly financial results: Q4 and FY 2018 results. Basel: Novartis; 2019. [cited 2019 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.novartis.com/sites/www.novartis.com/files/q4-2018-ir-presentation.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (KR) Sacubitril/valsartan. Wonju: HIRA; 2017-2018. [Google Scholar]