Human monkeypox virus is spreading in Europe and the USA among individuals who have not travelled to endemic areas.1 On July 23, 2022, monkeypox was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.2 Human-to-human transmission of monkeypox virus usually occurs through close contact with the lesions, body fluids, and respiratory droplets of infected people or animals.3 The possibility of sexual transmission is being investigated, as the current outbreak appears to be concentrated in men who have sex with men and has been associated with unexpected anal and genital lesions.1, 4 Whether domesticated cats and dogs could be a vector for monkeypox virus is unknown. Here we describe the first case of a dog with confirmed monkeypox virus infection that might have been acquired through human transmission.

Two men who have sex with men attended Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France, on June 10, 2022 (appendix). One man (referred to as patient 1 going forward) is Latino, aged 44 years, and lives with HIV with undetectable viral loads on antiretrovirals; the second man (patient 2) is White, aged 27 years, and HIV-negative. The men are non-exclusive partners living in the same household. They each signed a consent form for the use of their clinical and biological data, and for the publication of anonymised photographs. The men had presented with anal ulceration 6 days after sex with other partners. In patient 1, anal ulceration was followed by a vesiculopustular rash on the face, ears, and legs; in patient 2, on the legs and back. In both cases, rash was associated with asthenia, headaches, and fever 4 days later (figure A, B ).

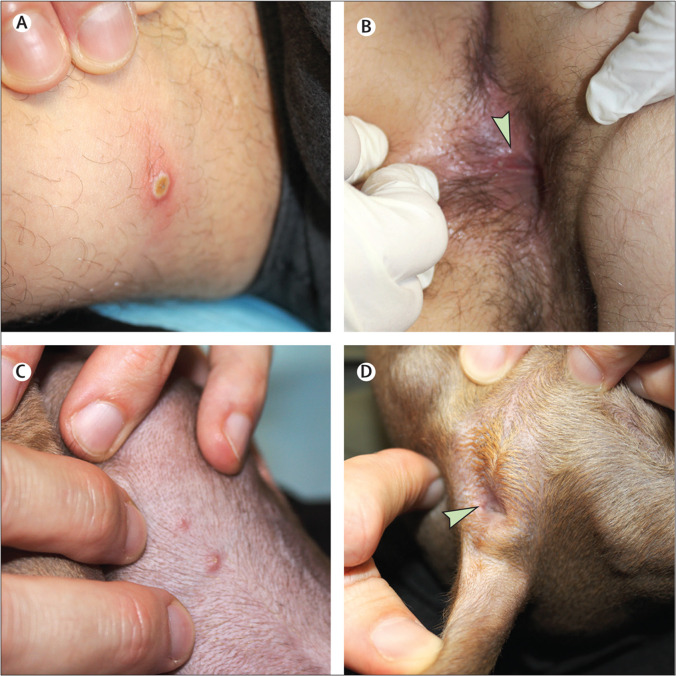

Figure.

Skin and mucosal lesions in two male patients and their dog with confirmed monkeypox virus

(A) Pustular lesion of the thigh, with central umbilication and the onset of necrosis, in patient 1. (B) Erosive and pustular anal lesions in patient 2. (C) Two slightly crusty erythematous papules in the dog. (D) Millimetric erosive anal lesion in the dog.

Monkeypox virus was assayed by real-time PCR (LightCycler 480 System; Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). In patient 1, virus was detected in skin and oropharynx samples; whereas in patient 2, virus was detected in anal and oropharynx samples.

12 days after symptom onset, their male Italian greyhound, aged 4 years and with no previous medical disorders, presented with mucocutaneous lesions, including abdomen pustules and a thin anal ulceration (figure C, D; appendix). The dog tested positive for monkeypox virus by use of a PCR protocol adapted from Li and colleagues5 that involved scraping skin lesions and swabbing the anus and oral cavity. Monkeypox virus DNA sequences from the dog and patient 1 were compared by next-generation sequencing (MinION; Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). Both samples contained virus of the hMPXV-1 clade, lineage B.1, which has been spreading in non-endemic countries since April, 2022, and, as of Aug 4, 2022, has infected more than 1700 people in France, mostly concentrated in Paris, where the dog first developed symptoms. Moreover, the virus that infected patient 1 and the virus that infected the dog showed 100% sequence homology on the 19·5 kilobase pairs sequenced.

The men reported co-sleeping with their dog. They had been careful to prevent their dog from contact with other pets or humans from the onset of their own symptoms (ie, 13 days before the dog started to present cutaneous manifestations).

In endemic countries, only wild animals (rodents and primates) have been found to carry monkeypox virus.6 However, transmission of monkeypox virus in prairie dogs has been described in the USA7 and in captive primates in Europe8 that were in contact with imported infected animals. Infection among domesticated animals, such as dogs and cats, has never been reported.

To the best of our knowledge, the kinetics of symptom onset in both patients and, subsequently, in their dog suggest human-to-dog transmission of monkeypox virus. Given the dog's skin and mucosal lesions as well as the positive monkeypox virus PCR results from anal and oral swabs, we hypothesise a real canine disease, not a simple carriage of the virus by close contact with humans or airborne transmission (or both). Our findings should prompt debate on the need to isolate pets from monkeypox virus-positive individuals. We call for further investigation on secondary transmissions via pets.

For monkeypox cases in France see https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/les-actualites/2022/cas-de-variole-du-singe-point-de-situation-au-4-aout-2022

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests. This work was supported by the French National Research Agency on HIV/Aids, Hepatitis and Emerging Infectious Diseases. We thank the patients and all the clinical and technical staff of the infectious diseases and virology departments of Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital (especially Anne-Geneviève Marcelin and Vincent Calvez) and Bichat-Claude Bernard Hospital, who provided care for the patients and conducted the virological explorations.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Thornhill JP, Barkati S, Walmsley S, et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries—April–June 2022. N Engl J Med. 2022 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207323. published online July 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenham C, Eccleston-Turner M. Monkeypox as a PHEIC: implications for global health governance. Lancet. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01437-4. published online Aug 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown K, Leggat PA. Human monkeypox: current state of knowledge and implications for the future. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2016;1:e8. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed1010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarín-Vicente EJ, Alemany A, Agud-Dios M, et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in Spain: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01436-2. published online Aug 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Zhao H, Wilkins K, Hughes C, Damon IK. Real-time PCR assays for the specific detection of monkeypox virus West African and Congo Basin strain DNA. J Virol Methods. 2010;169:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khodakevich L, Jezek Z, Kinzanzka K. Isolation of monkeypox virus from wild squirrel infected in nature. Lancet. 1986;1:98–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90748-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker S, Buller RM. A review of experimental and natural infections of animals with monkeypox virus between 1958 and 2012. Future Virol. 2013;8:129–157. doi: 10.2217/fvl.12.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arita I, Henderson DA. Smallpox and monkeypox in non-human primates. Bull World Health Organ. 1968;39:277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.