ABSTRACT

Zika virus (ZIKV) is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA arbovirus belonging to the genus Flavivirus. It was first isolated from a sentinel monkey in Uganda in 1947. More recently, ZIKV has undergone rapid geographic expansion and has been responsible for outbreaks in Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, and America. In this review, we have highlighted the influence of viral genetic variants on ZIKV pathogenesis. Two major ZIKV genotypes (African and Asian) have been identified. The Asian genotype is subdivided into Southwest Asia, Pacific Island, and American strains, and is responsible for most outbreaks. Non-synonymous mutations in ZIKV proteins C, prM, E, NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, and NS4B were found to have a higher prevalence and association with virulent strains of the Asian genotype. Consequently, the Asian genotype appears to have acquired higher cellular permissiveness, tissue persistence, and viral tropism in human neural cells. Therefore, mutations in specific coding regions of the Asian genotype may enhance ZIKV infectivity. Considering that mutations in the genomes of emerging viruses may lead to new virulent variants in humans, there is a potential for the re-emergence of new ZIKV cases in the future.

Keywords: Brazilian isolate, Congenital Zika syndrome, Mammalian cells, Sexual transmission route, Viral reservoir

INTRODUCTION

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a Flavivirus transmitted through the bite of female mosquitoes of the Aedes, Culex, and Anopheles genera 1 . Zika was first isolated from a Rhesus monkey in 1947 in Zika Forest, Uganda 2 . In 1954, the first case reported in humans was described on the African continent 3 . ZIKV was also detected in Asia in 1966 and has remained restricted to this region for almost five decades 4 .

In the early 2000s, ZIKV outbreaks were reported in regions of Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, and the Americas, with a proportional increase in infection rates. Outbreaks from Pacific Island and the Americas present higher numbers of cases 5 . In general, ZIKV had a higher epidemiological impact in tropical and subtropical countries once the mosquito Aedes spp. became a “cosmopolitan” vector, being widely distributed in tropical areas 1 . The first reported ZIKV outbreak occurred on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia, in 2007 6 . In 2013, ZIKV was associated with the development of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) in the Pacific Islands of French Polynesia 7 . In 2016, Brazil recorded 440,000-1,300,000 suspected cases and 2,975 cases of ZIKV-associated microcephaly 8 , which led the World Health Organization to declare a worldwide state of public health emergency 9 .

Acute ZIKV infections, known as Zika fever, generally result in mild illness in adults. The viral incubation period varies from 3 to 10 days, and most patients do not require hospitalization 5 . Zika fever is clinically characterized by fever, rash, fatigue, conjunctivitis, arthralgia, headache, myalgia, and retroorbital pain. These symptoms manifest in about 20-25% of symptomatic individuals. However, a small percentage of cases have been associated with neurological disorders in neonates (mainly microcephaly), a condition later named congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) 9 .

Decades later, efforts of the scientific community to identify a vector control method, as well as vaccines and treatments to combat ZIKV infection, continue. Similarly, elucidating the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this infection remain a challenge. During infection, host cells demonstrate morphological and molecular alterations 10 , 11 that eventually culminate in mitotic abnormalities and cell death 12 , leading to tissue loss and neurological injury 13 .

Many studies have shown that structural and nonstructural proteins are crucial components of viral pathogenesis 10 , 11 . However, it remains unclear which genetic factors of ZIKV may increase infection rate and virulence in humans. Here, we discuss the latest findings related to ZIKV genetic variants in terms of the infection process, cellular permissiveness, and tissue persistence.

ZIKV genome and life cycle

The ZIKV genomic organization is similar among members of the Flavivirus genus (Flaviviridae family) such as dengue virus (DENV), yellow fever virus (YFV), and West Nile virus (WNV) 14 . The ZIKV genome consists of 10,794 nucleotides in a single-stranded positive-sense RNA that encodes a polyprotein of 3,424 amino acids and 10 proteins crucial for the viral life cycle 10 . ZIKV RNA has two untranslated regions (UTRs) and a single open reading frame (ORF).

The 5′ and 3′ UTRs exhibit methylated nucleotides and non-polyadenylated forms, respectively, forming a loop structure. Moreover, the 5′ and 3′ UTRs have an essential function in virus replication. The 5′ UTR mediates the “start” signal for reading through the CAP AUG type 1 structure. Meanwhile, the 3′ UTR has a poly(A) tail that functions as a “stop” signal for the final step in polyprotein processing 15 , 16 . The ORF encodes three structural proteins (E, prM, and C) and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) 10 .

ZIKV must undergo attachment, entry, replication, and exocytosis to successfully infect human cells. ZIKV cell attachment is mediated by attachment factors such as negatively charged glycosaminoglycans 17 . These molecules retain viral particles on the cell surface, providing conditions for membrane fusion. The entry process occurs via ZIKV envelope protein E 18 , which interacts with entry receptors in the host cell, such as C-type lectin 19 and phosphatidylserine (PS) receptors 20 . These interactions cause conformational changes in the cell membrane and induce clathrin-mediated endocytosis, allowing the release of the viral genome into the cytoplasm 21 .

Considering this, C-type lectin receptors, such as DC-SIGN (dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin) and L-SIGN (liver/lymph node-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing integrin) recognize N-glycans linked to viral protein E, allowing viral entry 18 , 19 , whereas PS (present in the ZIKV envelope) is recognized by PS receptors, such as TAM (Tyro3, Axl, and Mer) and TIM (TIM1, TIM3, and TIM4) 20 .

ZIKV protein E is the largest antigenic glycoprotein in flaviviruses and plays a role in adhesion, recognition, and fusion to the host cell. The dimeric structure of protein E contains an ectodomain with three domains: DI, DII, and DIII 18 , 19 , 22 . DI has a structural function in that it acts as a binder and chemical support for other domains. DII interacts and promotes fusion on the cell membrane through a loop-shaped structure located on the support loop with DI 18 . DIII is an immunoglobulin-like domain with the capacity to bind extracellular receptors 23 , 24 . Protein E contains a glycosylation site in an asparagine residue (Asn154), which may be associated with ZIKV virulence.

This pattern of N-glycosylation is conserved among DENV, YFV, and WNV. In DENV, glycosylation follows the Asn154 and Asn67 residues 19 . According to Wen 18 , N-glycosylated residues on protein E may enhance ZIKV infectivity by increasing the affinity of protein E to the entry receptors.

Once inside the cell, the low pH within the endosome enables the native state of protein E, which subsequently fuses to the endosome membrane and releases the viral RNA into the cytoplasm. Once in the cytoplasm, ZIKV undergoes particle assembly, followed by RNA replication and translation into viral proteins 25 . During maturation, newly assembled viral particles enter the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and acquire PS. Viral particles then migrate from the ER to the Golgi complex where viral maturation occurs 26 . This process is mediated by the protein furin in the host, which cleaves the prM protein into the “pr” and “M” portions 22 , 25 . Finally, new mature ZIKV viral particles are released into the extracellular environment 22 .

ZIKV genotypes

To date, two major ZIKV genotypes have been identified: African and Asian. The African-ZIKV genotype has caused sporadic or recurrent infections in West African countries, with clinical manifestations of fever, conjunctivitis, and myalgia 3 , 27 . Nevertheless, the Asian-ZIKV genotype has circulated in Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, and the Americas, causing major outbreaks characterized by fever, arthralgia, conjunctivitis, CSZ, GBS, and ophthalmological anomalies 6 , 7 , 9 , 28 . Through the timespan of these major outbreaks, it has been reported that the number of people with severe symptoms has increased as the Asian-ZIKV epidemic has disseminated among continents 29 , 30 .

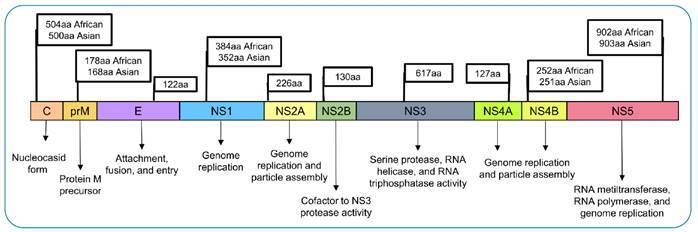

The African-ZIKV genotype is subdivided into East African and West African strains. The Asian-ZIKV genotype is subdivided into Southwest Asia, Pacific Island, and American strains 31 . The African and Asian genotypes exhibit few different amino acid sequences 14 . Nevertheless, they share subcellular locations in host cells and protein function. ZIKV polyprotein from African and Asian genotypes are schematized in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1: ZIKV polyprotein from the African- and Asian-ZIKV genotypes, structural proteins (C, prM, and E) and nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) as well as their sizes, in amino acids (aa), and functions in the viral cycle.

Shrivastava 32 and Collins 33 observed phylogenetic diversity in both African and Asian-ZIKV genotypes as well as insertions/deletions in their viral genomes. Moreover, Barzilai and Schrago 34 posited that ZIKV spread may be associated with nonsynonymous mutations as a consequence of the viral evolution rate. Overall, Asian genotypes (lineages from Malaysia, Cambodia, and America) show higher genetic variants and single nucleotide variants in the viral genome than African genotypes (East and West African lineages) 32 - 34 .

According to Collins 33 , the African genotype exhibits fewer synonymous mutations (G3589T, G3589A, C5080A, and C5080T) and nonsynonymous mutations (G3299A, A3300G, and T5079A) than the Asian genotype, with 18 nonsynonymous mutations and only one synonymous mutation. This may explain why both African strains remained restricted to the African continent 32 .

Taking into consideration the coding region sequences in the Asian genotype, Faria 35 and Ye 14 found great genetic similarities between ZIKV strains from the Pacific Islands and the Americas. However, these ZIKV strains exhibited a phylogenetic distance of decades compared to strains from Malaysia, which were later identified as a Southeast Asian strain 35 . In addition to phylogenetic differences, dissimilar nucleotides were also found between strains from the Pacific Islands and Malaysia 14 , 35 , indicating that these Asian strains do not share the same lineage. ZIKV strains from the Pacific Islands and Americas constitute only one lineage within the Asian genotype 14 , 35 . Among the lineages of the Asian genotype, Malaysian strains sampled in 1966 were the oldest 35 .

Ye 14 suggested that the American strain constitutes a new clade within the Asian-ZIKV genotype. Reports also indicated a common origin among ZIKV strains from Micronesia, French Polynesia, and Brazil during outbreaks in 2007, 2013, and 2016, respectively 14 , 31 , 36 . However, many reports indicate that there are variations among amino acids throughout the Asian-ZIKV genome, which can lead to viral adaptations (Table 1). In this context, a study conducted by Kawai 31 evaluated the pathogenicity of Southern Asian, Pacific Island, and American strains in vitro and in vivo. It has been shown that the American strain induces strong pathogenicity 31 .

TABLE 1: Characterization of nonsynonymous mutations on the Asian-ZIKV genome.

| Protein | Polyprotein position | Isolates | Substitution* | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 81 | Malaysia | I → M | 32 |

| 81 | Thailand | I → M | 32 | |

| 81 | México | I → M | 32 | |

| 81 | Honduras | I → M | 32 | |

| prM | 139 | French Polynesia | S → N | 40 |

| 139 | Brazil | S → N | 40 | |

| 168 | Malaysia | D → K | 32 | |

| E | 356 | China | D → N | 43 |

| 451 | Colombia | D → E | 32 | |

| 451 | Panama | D → E | 32 | |

| 456 | Brazil | R → K | 37 | |

| 763 | China | V → M | 42 | |

| 600 | Thailand | A → E | 24 | |

| 620 | Puerto Rico | V → L | 32 | |

| 620 | Malaysia | L → V | 32 | |

| 683 | Thailand | E → K | 24 | |

| 691 | Malaysia | Y → H, H → Y | 32 | |

| NS1 | 852 | Panama | F → S | 33 |

| 969 | Honduras | Y → S | 33 | |

| 1033 | Colombia | S → N | 32 | |

| 1033 | Porto Rico | S → N | 32 | |

| 1033 | Panama | S → N | 32 | |

| 1143 | Brazil | V → M | 37 | |

| NS2A | 1176 | Brazil | T → I, I → T | 37 |

| 1180 | Brazil | I → Y, T → I | 37 | |

| 1263 | Brazil | V → A | 37 | |

| 1263 | Malaysia | V → A | 32 | |

| 1263 | Thailand | A → V | 32 | |

| 1303 | Panama | A → V | 32 | |

| 1303 | Malaysia | V → A | 32 | |

| 1327 | Brazil | M → V, V → M | 37 | |

| 1370 | Honduras | G → R | 33 | |

| NS2B | 1411 | Cambodia | I → T | 38 |

| NS3 | 1594 | Brazil | H → Y, Y → H | 37 |

| 1857 | Thailand | H → Y | 24 | |

| NS4B | 2295 | Brazil | I → T | 37 |

| 2857 | China | E → D | 41 |

*I: isoleucine; M: methionine; S: serine; N: asparagine; D: aspartic acid; K: lysine; E: glutamic acid; R: arginine; V: valine; L: leucine; Y: tyrosine; T: threonine; A: alanine; G: glycine; H: histidine.

In addition, Strottmann 37 and Regla-Nava 38 suggested that mutations in NS2A (A117V) and NS2B (I39V) from Asian strains may impact the infectivity of mammalian and insect cells. Using an in silico approach, mutations with relevant structural impacts were found in protein C (I80T) and NS2A (K113F, A143V, and I199V) of circulating ZIKV strains from French Polynesia, Brazil, and Colombia 39 . Strottman 37 detected nonsynonymous mutations in proteins E (R166K), NS1 (V349M), NS2A (I30T, T34I, V117R, and V1181M), NS3 (H92Y), and NS4B (I26T) of three ZIKV isolates from Brazilian regions.

Other in vitro and in vivo studies have been conducted to elucidate the impact of nonsynonymous mutations on the Asian-ZIKV genome. Yan 40 demonstrated that the mutation S139N in prM of the Asian genotype may contribute to the development of CZS. This mutation in the prM protein was detected before the outbreak in French Polynesia, and it remained stable during ZIKV spread until the outbreak in the Americas in 2015 40 . In the viral protein NS4B, the substitution E2587D was observed in an Asian strain from China, in 2016 41 . Moreover, two substitutions in protein E (D67N and V473M) may have increased ZIKV replication and neurovirulence as well as its transmission during pregnancy and viremia after the American epidemic 42 , 43 . In an Asian isolate from a Thai patient in 2021, unique nonsynonymous mutations were detected in proteins E (A310E and E393K) and NS3 (H355Y) 24 . These findings suggest that after the outbreak in French Polynesia and before the outbreak in the Americas, ZIKV strains might have mutated and acquired higher infectivity.

Moreover, Li 44 proposed that proteins E, C, and prM contribute to Asian-ZIKV attachment, permissiveness, and cytopathic effects in human glial cells. In addition, NS2A recruits unprocessed proteins to be cleaved by NS2B/NS3 serine-protease at the E-prM-C site 45 . NS2A and NS4B also play a role in the assembly of new particles 11 . Haddow 36 demonstrated that ZIKV genotypes can exhibit different N-glycosylation sites, whereas Bos 46 found new glycosylated residues in protein E (I152, T156, and H158) in Brazilian ZIKV strains. Highly glycosylated residues may influence ZIKV attachment, entry, and fusion with host cells 46 .

Cellular permissiveness of ZIKV

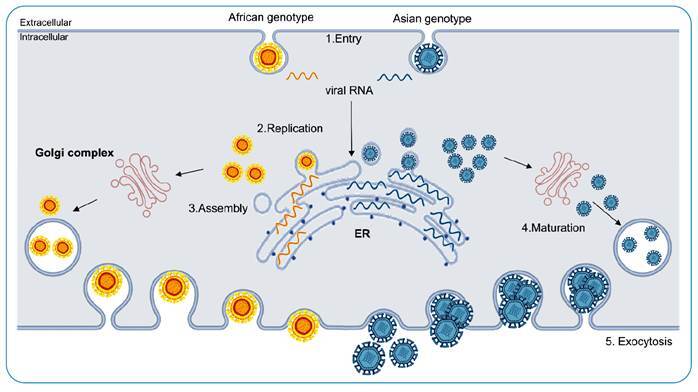

ZIKV is known to infect different hosts, ranging from mosquitoes to mammals, as well as many cell types and tissues (Figure 2). Rat mesenchymal stem cells, mouse embryonic fibroblasts, murine macrophages, monkey kidneys, and mosquito larvae cells are some non-human cellular models that have been described as susceptible to ZIKV entry, replication, and release 47 .

FIGURE 2: Permissiveness and replication cycle of the ZIKV genotypes in host cell.

The entry processes of African and Asian genotypes in humans share a highly conserved mechanism that requires clathrin-mediated endocytosis 21 . Among human cells, ZIKV is known to infect dermal fibroblasts 48 , fetal neurons 49 , primary Hofbauer 50 and mesenchymal stem cells 47 , epidermal keratinocytes 48 , fetal cortical astrocytes 49 , primary trophoblasts 50 , embryonic kidney cells 47 , and sperm cells 51 . Furthermore, some types of innate immune cells (such as primary monocytes and plasmacytoid dendritic cells) have been identified as permissive to viral infectivity 30 .

During ZIKV infection, the skin cells mediate an early innate immune response 48 . In vitro studies have evaluated the persistence of ZIKV infection in human skin cells in an attempt to understand the infection route following mosquito bites in mammalian hosts. Hamel 52 observed that human epidermal keratinocytes, dermal fibroblasts, and immature dendritic cells were fully permissive to French Polynesia isolates. However, Hou 26 showed that fibroblasts and epidermal human lineages did not display any differences in permissiveness, infection rate, and replication modes between isolates from Uganda and Puerto Rico.

According to Hou 26 , immunological cells did not demonstrate a difference in permissiveness between African- and Asian-ZIKV genotypes. However, Osterlund 53 observed differences in replication rates among these genotypes, although both showed great replication in human dendritic cells. Unlike the African genotype, viral replication in the Asian genotype is attenuated in human macrophages 53 . These findings suggest that the Asian-ZIKV genotype may use immunological cells as a viral reservoir.

Tissue persistence and viral tropism

During ZIKV infection, some cells and tissues may become viral reservoirs, contributing to the dissemination of Asian-ZIKV to nearby tissues. It was observed in vitro that both ZIKV genotypes have the capacity to infect human peripheral blood mononuclear cells 26 , indicating that these cells may act as an “entry door” for ZIKV spread.

Moreover, ZIKV-infected monocytes exhibited a quicker transmigration process than cell-free viruses on endothelial barriers in studies using in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo models 30 . ZIKV-infected mast cells were also detected in situ in the placental tissue of pregnant Brazilian women 54 . These reports indicate that ZIKV-infected immunological cells might circulate throughout the host’s blood tissue, promoting Asian-ZIKV spread and contributing to vertical transmission.

Asian-ZIKV has also been found to be transmitted by the sexual route. For instance, Rashid 55 observed the infection and replication of ZIKV (isolates from Puerto Rico) in primary human Sertoli cells in vitro, confirming ZIKV persistence in the reproductive tract and high cellular permissiveness. In addition, Matulasi 51 demonstrated that ZIKV isolates from French Polynesia infect reproductive and somatic testicular cells in vitro, as well as, replicates in human testes ex vivo. These studies suggest that American ZIKV strains can replicate in the male reproductive system.

In this context, ZIKV-infected sperm cells can also infect tissues of the female reproductive system during sexual encounters. Using an in vitro approach, studies have demonstrated that human primary endometrial 56 , Hofbauer, and trophoblast cells 50 are vulnerable target cells of American ZIKV strains. Thus, once ZIKV infects and replicates in reproductive tissues, it poses a risk at different stages of pregnancy.

Considering that neuronal progenitor cells and glial cells, which are crucial for neurogenesis, can also be targeted by ZIKV, the central nervous system (CNS) inflammatory process during gestation can significantly impact brain development. Hence, diverse studies have shown positive tropism between ZIKV genotypes and cells in the CNS. Li 57 demonstrated that both African and Asian genotypes can infect and replicate in neurons and glial cells in vitro. In parallel, in vitro astrocytes have a good tolerance for high viral load rates for both viral genotypes 49 . However, according to Goodfellow 58 and Aguiar 59 , loss of cellular proliferation, neuronal migration, and abnormal extracellular matrix have been observed only in infections caused by the Asian genotype. In addition, Cugola 60 proposed that ZIKV strains that circulate in Brazil can trigger autophagy and apoptotic pathways, leading to cell death in cortical progenitor cells.

Thus, compared to African isolates, Brazilian ZIKV isolates exhibited higher neurotropism for neural cell lineages. These data led us to believe that the Asian genotype has greater virulence because its strains have accumulated large nonsynonymous mutations over the time of dissemination.

CONCLUSIONS

We gathered information on the genetic variants of ZIKV and their influence on the viral life cycle, cellular permissiveness, and tissue persistence. Based on the reviewed papers, we found that nonsynonymous mutations in the ZIKV genome may increase viral entry, RNA replication, particle assembly, and viral load. Considering that mutations in the genomes of emerging viruses may lead to new virulent variants in humans, this might be a possibility for the future re-emergence of new cases. Further in vitro and in vivo experiments are required to better evaluate these mutations.

Footnotes

Financial Support: This study was financed by the National Council for the Improvement of Higher Education - Brazil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001, National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - Brazil (CNPq) and the Department of Science and Technology of the Ministry of Health - Brazil (Decit/SCTIE/MS).

REFERENCES

- 1.Boyer S, Calvez E, Chouin-Carneiro T, Diallo D, Failloux AB. An overview of mosquito vectors of Zika virus. Microbes Infect. 2018;20(11-12):646–660. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dick GW, Kitchen S, Haddow A. Zika Virus (I). Isolations and serological specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1952;46(5):509–520. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(52)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacNamara FN. Zika virus: A report on three cases of human infection during an epidemic of jaundice in Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1954;48(2):139–145. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(54)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia R, Marchette NJ, Rudnick A. Isolation of Zika Virus from Aedes Aegypti Mosquitoes in Malaysia *. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;18(3):411–415. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1969.18.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazmi SS, Ali W, Bibi N, Nouroz F. A review on Zika virus outbreak, epidemiology, transmission and infection dynamics. J Biol Res. 2020;27(1):5–5. doi: 10.1186/s40709-020-00115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, et al. Zika Virus Outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2536–2543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao-Lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, Lastère S, Roche C, Vanhomwegen J, et al. Guillain-Barré Syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: A case-control study. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1531–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heukelbach J, Alencar CH, Kelvin AA, De Oliveira WK, Pamplona de Góes Cavalcanti L. Zika virus outbreak in Brazil. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2016;10(2):116–120. doi: 10.3855/jidc.8217. https://jidc.org/index.php/journal/article/view/26927450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization Fourth Meeting of the Emergency Committee Under the International Health Regulations (2005) Regarding Microcephaly, Other Neurological Disorders and Zika Virus. Apr 28, 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/18-11-2016-fifth-meeting-of-the-emergency-committee-under-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-regarding-microcephaly-other-neurological-disorders-and-zika-virus

- 10.Hou W, Cruz-Cosme R, Armstrong N, Obwolo LA, Wen F, Hu W, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of the genes encoding the proteins of Zika virus. Gene. 2017;628:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.07.049. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0378111917305723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li G, Poulsen M, Fenyvuesvolgyi C, Yashiroda Y, Yoshida M, Simard JM, et al. Characterization of cytopathic factors through genome-wide analysis of the Zika viral proteins in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(3):E376-85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619735114. http://www.pnas.org/lookup//10.1073/pnas.1619735114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Souza BSF, Sampaio GLA, Pereira CS, Campos GS, Sardi SI, Freitas LAR, et al. Zika virus infection induces mitosis abnormalities and apoptotic cell death of human neural progenitor cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):39775–39775. doi: 10.1038/srep39775. http://www.nature.com/articles/srep39775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azevedo RSS, Sousa JR, Araujo MTF, Martins AJ, Filho, Alcantara BN, Araujo FMC, et al. In situ immune response and mechanisms of cell damage in central nervous system of fatal cases microcephaly by Zika virus. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17765-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye Q, Liu ZY, Han JF, Jiang T, Li XF, Qin CF. Genomic characterization and phylogenetic analysis of Zika virus circulating in the Americas. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;43:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemert VF, Berkhout B. Nucleotide composition of the Zika virus RNA genome and its codon usage. Virol J. 2016;13(1):95–95. doi: 10.1186/s12985-016-0551-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huber RG, Lim XN, Ng WC, Sim AYL, Poh HX, Shen Y, et al. Structure mapping of dengue and Zika viruses reveals functional long-range interactions. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1408–1408. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09391-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SY, Zhao J, Liu X, Fraser K, Lin L, Zhang X, et al. Interaction of Zika Virus Envelope Protein with Glycosaminoglycans. Biochemistry. 2017;56(8):1151–1162. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wen D, Li S, Dong F, Zhang Y, Lin Y, Wang J, et al. N-glycosylation of viral e protein is the determinant for vector midgut invasion by flaviviruses. MBio. 2018;9(1):1–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00046-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carbaugh DL, Baric RS, Lazear HM. Envelope Protein Glycosylation Mediates Zika Virus Pathogenesis. Dermody TS, editor. J Virol. 2019;93(12) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00113-19. https://jvi.asm.org/content/93/12/e00113-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meertens L, Carnec X, Lecoin MP, Ramdasi R, Guivel-Benhassine F, Lew E, et al. The TIM and TAM Families of Phosphatidylserine Receptors Mediate Dengue Virus Entry. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(4):544–557. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.08.009.S1931312812003046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rinkenberger N, Schoggins JW. Comparative analysis of viral entry for Asian and African lineages of Zika virus. Virology. 2019;533:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2019.04.008.S0042682219301084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliveira ERA, Alencastro RB, Horta BAC. New insights into flavivirus biology: the influence of pH over interactions between prM and E proteins. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2017;31(11):1009–1019. doi: 10.1007/s10822-017-0076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SI, Kim S, Shim JM, Lee HJ, Chang SY, Park S, et al. Neutralization of Zika virus by E protein domain III-Specific human monoclonal antibody. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;545:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaimipuk T, Sachdev S, Yoksan S, Thepparit C. A Small-Plaque Isolate of the Zika Virus with Envelope Domain III Mutations Affect Viral Entry and Replication in Mammalian but Not Mosquito Cells. Viruses. 2022;14(3):480–480. doi: 10.3390/v14030480. https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/14/3/480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owczarek K, Chykunova Y, Jassoy C, Maksym B, Rajfur Z, Pyrc K. Zika virus: mapping and reprogramming the entry. Cell Commun Signal. 2019;17(1):41–41. doi: 10.1186/s12964-019-0349-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hou W, Armstrong N, Obwolo LA, Thomas M, Pang X, Jones KS, et al. Determination of the Cell Permissiveness Spectrum, Mode of RNA Replication, and RNA-Protein Interaction of Zika Virus. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2338-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchi S, Viviani S, Montomoli E, Tang Y, Boccuto A, Vicenti I, et al. Zika Virus in West Africa: A Seroepidemiological Study between 2007 and 2012. Viruses. 2020;12(6):641–641. doi: 10.3390/v12060641. https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/12/6/641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IML, Horovitz DDG, Cavalcanti DP, Pessoa A, et al. Possible Association Between Zika Virus Infection and Microcephaly - Brazil, 2015. [2021 April 28];Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6503e2. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6503e2.htm . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pettersson JHO, Bohlin J, Dupont-Rouzeyrol M, Brynildsrud OB, Alfsnes K, Cao-Lormeau VM, et al. Re-visiting the evolution, dispersal and epidemiology of Zika virus in Asia article. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayala-Nunez NV, Follain G, Delalande F, Hirschler A, Partiot E, Hale GL, et al. Zika virus enhances monocyte adhesion and transmigration favoring viral dissemination to neural cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1–16. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12408-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawai Y, Nakayama E, Takahashi K, Taniguchi S, Shibasaki K, Kato F, et al. Increased growth ability and pathogenicity of american-and pacific-subtype zika virus (ZIKV) strains compared with a southeast asian-subtype ZIKV strain. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(6):1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shrivastava S, Puri V, Dilley KA, Ngouajio E, Shifflett J, Oldfield LM, et al. Whole genome sequencing, variant analysis, phylogenetics, and deep sequencing of Zika virus strains. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins ND, Widen SG, Li L, Swetnam DM, Shi PY, Tesh RB, et al. Inter- and intra-lineage genetic diversity of wild-type Zika viruses reveals both common and distinctive nucleotide variants and clusters of genomic diversity. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8(1):1126–1138. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1645572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barzilai LP, Schrago CG. The range of sampling times affects Zika virus evolutionary rates and divergence times. Arch Virol. 2019;164(12):3027–3034. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019-04430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faria NR, Azevedo RSS, Kraemer MUG, Souza R, Cunha MS, Hill SC, et al. Zika virus in the Americas: Early epidemiological and genetic findings. Science. 2016;352(6283):345–349. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haddow AD, Schuh AJ, Yasuda CY, Kasper MR, Heang V, Huy R, et al. Genetic characterization of zika virus strains: Geographic expansion of the asian lineage. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(2):e1477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strottmann DM, Zanluca C, Mosimann ALP, Koishi AC, Auwerter NC, Faoro H, et al. Genetic and biological characterization of zika virus isolates from different Brazilian regions. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2019;114(7):1–11. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760190150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Regla-Nava JA, Wang YT, Fontes-Garfias CR, Liu Y, Syed T, Susantono M, et al. A Zika virus mutation enhances transmission potential and confers escape from protective dengue virus immunity. Cell Rep. 2022;39(2):110655–110655. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agrelli A, Moura RR, Crovella S, Brandão LAC. Mutational landscape of Zika virus strains worldwide and its structural impact on proteins. Gene. 2019;708:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2019.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan L, Huang XY, Liu ZY, Zhang F, Zhu XL, Yu JY, et al. A single mutation in the prM protein of Zika virus contributes to fetal microcephaly. Science. 2017;358(6365):933–936. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li S, Shi Y, Zheng K, Dai J, Li X, Yuan S, et al. Morphologic and molecular characterization of a strain of zika virus imported into Guangdong, China. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collette NM, Lao VHI, Weilhammer DR, Zingg B, Cohen SD, Hwang M, et al. Single Amino Acid Mutations Affect Zika Virus Replication In Vitro and Virulence In Vivo. Viruses. 2020;12(11):1295–1295. doi: 10.3390/v12111295. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33198111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Z, Zhang Y, Cheng M, Ge N, Shu J, Xu Z, et al. A single nonsynonymous mutation on ZIKV E protein-coding sequences leads to markedly increased neurovirulence in vivo. Virol Sin. 2022;37(1):115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2022.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li G, Bos S, Tsetsarkin KA, Pletnev AG, Desprès P, Gadea G, et al. The roles of prM-E proteins in historical and epidemic zika virus-mediated infection and neurocytotoxicity. Viruses. 2019;11(2):157–157. doi: 10.3390/v11020157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang X, Xie X, Xia H, Zou J, Huang L, Popov VL, et al. Zika Virus NS2A-Mediated Virion Assembly. Horner SM, editor. MBio. 2019;10(5):1–21. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02375-19. https://mbio.asm.org/content/10/5/e02375-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bos S, Viranaicken W, Frumence E, Li G, Desprès P, Zhao RY, et al. The Envelope Residues E152/156/158 of Zika Virus Influence the Early Stages of Virus Infection in Human Cells. Cells. 2019;8(11):1–15. doi: 10.3390/cells8111444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramos da Silva S, Cheng F, Huang IC, Jung JU, Gao SJ. Efficiencies and kinetics of infection in different cell types/lines by African and Asian strains of Zika virus. J Med Virol. 2019;91(2):179–189. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim JA, Seong RK, Son SW, Shin OS. Insights into ZIKV-Mediated Innate Immune Responses in Human Dermal Fibroblasts and Epidermal Keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(2):391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jorgačevski J, Korva M, Potokar M, Lisjak M, Avšič-Županc T, Zorec R. ZIKV Strains Differentially Affect Survival of Human Fetal Astrocytes versus Neurons and Traffic of ZIKV-Laden Endocytotic Compartments. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8069–8069. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44559-8. http://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-44559-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gavegnano C, Bassit LC, Cox BD, Hsiao HM, Johnson EL, Suthar M, et al. Jak Inhibitors Modulate Production of Replication Competent Zika Virus in Human Hofbauer, Trophoblasts, and Neuroblastoma cells. Pathog Immun. 2017;2(2):199–199. doi: 10.20411/pai.v2i2.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matusali G, Houzet L, Satie AP, Mahé D, Aubry F, Couderc T, et al. Zika virus infects human testicular tissue and germ cells. J Clin Invest. 2018 Sep 10;128(10):4697–4710. doi: 10.1172/JCI121735. https://www.jci.org/articles/view/121735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamel R, Dejarnac O, Wichit S, Ekchariyawat P, Neyret A, Luplertlop N, et al. Biology of Zika Virus Infection in Human Skin Cells. J Virol. 2015;89(17):8880–8896. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00354-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Österlund P, Jiang M, Westenius V, Kuivanen S, Järvi R, Kakkola L, et al. Asian and African lineage Zika viruses show differential replication and innate immune responses in human dendritic cells and macrophages. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52307-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rabelo K, Gonçalves AJ da S, Souza LJ de, Sales AP, Lima SMB de, Trindade GF, et al. Zika Virus Infects Human Placental Mast Cells and the HMC-1 Cell Line, and Triggers Degranulation, Cytokine Release and Ultrastructural Changes. Cells. 2020;9(4):975–975. doi: 10.3390/cells9040975. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/9/4/975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rashid M, Zahedi-Amiri A, Glover KKM, Gao A, Nickol ME, Kindrachuk J, et al. Zika virus dysregulates human Sertoli cell proteins involved in spermatogenesis with little effect on tight junctions. Singh SK, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(6):e0008335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pagani I, Ghezzi S, Ulisse A, Rubio A, Turrini F, Garavaglia E, et al. Human endometrial stromal cells are highly permissive to productive infection by zika virus. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep44286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li H, Saucedo-Cuevas L, Yuan L, Ross D, Johansen A, Sands D, et al. Zika Virus Protease Cleavage of Host Protein Septin-2 Mediates Mitotic Defects in Neural Progenitors. Neuron. 2019;101(6):1089-1098.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goodfellow FT, Willard KA, Stice SL, Brindley MA, Wu X, Scoville S. Strain-dependent consequences of zika virus infection and differential impact on neural development. Viruses. 2018;10(10) doi: 10.3390/v10100550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aguiar RS, Pohl F, Morais GL, Nogueira FCS, Carvalho JB, Guida L, et al. Molecular alterations in the extracellular matrix in the brains of newborns with congenital Zika syndrome. Sci Signal. 2020;13(635) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aay6736. https://stke.sciencemag.org/lookup//10.1126/scisignal.aay6736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cugola FR, Fernandes IR, Russo FB, Freitas BC, Dias JLM, Guimarães KP, et al. The Brazilian Zika virus strain causes birth defects in experimental models. Nature. 2016;534(7606):267–271. doi: 10.1038/nature18296. http://www.nature.com/articles/nature18296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]