Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate whether a larger tissue volume increases the sensitivity of detecting alpha-synuclein (AS) pathology in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

Methods

Nine patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) or idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep disorder (iRBD) who underwent GI operation and had full-depth intestinal blocks were included. All patients were selected from our previous study population. A total of 10 slides (5 serial sections from the proximal and distal blocks) per patient were analyzed.

Results

In previous studies, pathologic evaluation revealed phosphorylated AS (+) in 5/9 patients (55.6%) and in 1/5 controls (20.0%); in this extensive examination, this increased to 8/9 patients (88.9%) but remained the same in controls (20.0%). The severity and distribution of positive findings were similar between patients with iRBD and PD.

Conclusion

Examining a large tissue volume increased the sensitivity of detecting AS accumulation in the GI tract.

Keywords: Alpha-synuclein, Synucleinopathy, Gastrointestinal tract, Immunohistochemistry, Volume

Lewy pathology of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract has potential as a biomarker for the diagnosis of synucleinopathies such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep disorder (iRBD). However, low sensitivity limits its use in clinical practice [1]. In a previous autopsy study, evaluation of multiple sections increased the positivity rate [2], and earlier in vivo studies reported high sensitivity using a method called ‘whole-mount staining.’ [3-5]

Therefore, this study aimed to determine whether evaluation of a larger tissue volume increases the sensitivity of detecting alpha-synuclein (AS) pathology in the GI tract in patients with synucleinopathy.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Participants and specimen selection

Patients in this study were selected from those who participated in previous studies of PD [1] and iRBD [6]. We selected patients with PD or iRBD, and controls who had both proximal and distal marginal blocks of the GI tract archived in the pathology bank. Therefore, two formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks were collected per participant. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. H-1409-043-608). The requirements for a waiver of informed consent were met, and a waiver was granted.

Immunohistochemistry

A total of five serial 3-μm sections were obtained from each surgical block for immunohistochemistry (IHC). The paraffin sections were mounted on a glass slide, dewaxed, rehydrated, and incubated with primary antibodies on automated machines as previously described [1,6]. A primary antibody against phosphorylated AS (pAS) (1/1,000 anti-pAS at serine 129 monoclonal Ab [EP1536Y]; Abcam ab51253, Cambridge, UK) was used in conjunction with the Leica Bond Max (A33030) system, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Bound antibodies were detected using the Bond Polymer Refine Detection system (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Pathologic evaluation

To avoid bias, the raters were blinded to the clinical information of the participants. All stained slides were scanned with a Leica Slide Scanner (Aperio AT2, Leica Biosystems). Anonymized digital slides were evaluated using the Pathologic Slide Viewing Software (Aperio ImageScope ver. 12.4, Leica Biosystems).

pAS positive findings were defined conservatively as in the previous study [6]: 1) pAS IHC showing definite and clear staining such as ‘dots and fiber’ or ‘Lewy body-like staining’ pattern, as the consensus paper suggested [7] and 2) localization in neural structures confirmed with anatomic inspection [8]. pAS-positive findings were semiquantitatively rated as grade 1, 2, or 3, which corresponded to sparse, moderate, or frequent in the multicenter study [6,7].

A neuropathologist (S.K) and neurologist (C.S) were blinded to the anonymization procedure and independently examined the slides. The neurologist (C.S) participated in previous studies regarding GI synucleinopathy [1,6,8], and both raters underwent a training program in the microscopic reading of peripheral AS pathology of the Systemic Synuclein Sampling Study [9]. Any discrepancy between the two raters was resolved in a consensus meeting with independent investigators (S.P and B.J).

Statistical analysis

This study is an additional analysis of two previous studies, and the subjects were not randomly selected. Therefore, descriptive analyses were mainly conducted. For group comparison, nonparametric tests were used because of the small number of participants. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS ver. 26.0.0.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

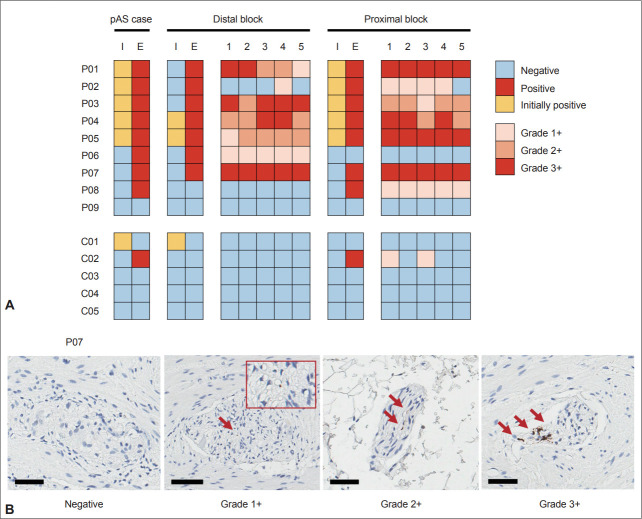

Nine patients (4 PD and 5 iRBD) and five controls were selected. In previous studies, pAS was positive in 5/9 patients (55.6%) and 1/5 controls (20.0%). In an extensive evaluation of 10 slides per patient, the positivity rate increased to 8/9 patients (88.9%), but the rate remained the same (20.0%) in controls (p = 0.023; Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

pAS immunostaining results of extensive tissue (5 slides per block) compared with original staining findings

| Group | ID | Diagnosis | PD subtype | Duration of disease onset to operation (yr) | Specimen | pAS result |

Distal block |

Proximal block |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial* | Extensive | Initial* | Extensive | Highest grade | N of positive slides | Initial* | Extensive | Highest grade | N of positive slides | ||||||

| Patient | P01 | PD | TD | 1 | Stomach | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 3+ | 5 | (+) | (+) | 3+ | 5 |

| Patient | P02 | PD | TD | -2 | Proximal colon | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 1+ | 1 | (+) | (+) | 1+ | 4 |

| Patient | P03 | iRBD | -2 | Stomach | (+) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 3+ | 5 | (+) | (+) | 2+ | 5 | |

| Patient | P04 | iRBD | -1 | Esophagus | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 3+ | 5 | (+) | (+) | 3+ | 5 | |

| Patient | P05 | iRBD | 0 | Stomach | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | 2+ | 5 | (+) | (+) | 3+ | 5 | |

| Patient | P06 | PD | TD | 5 | Proximal colon | (-) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 1+ | 5 | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 |

| Patient | P07 | PD | PIGD | 1 | Stomach | (-) | (+) | (-) | (+) | 3+ | 5 | (-) | (+) | 3+ | 5 |

| Patient | P08 | iRBD | -1 | Stomach | (-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 | (-) | (+) | 1+ | 5 | |

| Patient | P09 | iRBD | -3 | Stomach | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 | |

| Control | C01 | Proximal colon | (+) | (-) | (+) | (-) | 0 | 0 | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Control | C02 | Proximal colon | (-) | (+) | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 | (-) | (+) | 1+ | 2 | |||

| Control | C03 | Stomach | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Control | C04 | Stomach | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Control | C05 | Stomach | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 | (-) | (-) | 0 | 0 | |||

initial result is retrieved from immunostaining data of previous studies which stained one slide per block.

pAS, phosphorylated alpha-synuclein; PD, Parkinson’s disease; iRBD, idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep disorder; TD, tremor-dominant; PIGD, postural instability gait disturbance.

Figure 1.

pAS immunostaining results of extensive tissue evaluation (five sequential slides per block) compared with original staining findings. A: The first and second columns compare the pAS positivity results from previous studies (I) [6,8] with the current extensive evaluation (E). The pAS staining results of distal and proximal blocks are also presented. When discordant results were obtained between proximal and distal blocks, only mild positive findings (semiquantitative grade 1) were present (i.e., the three subjects P06, P08, and C02). Moreover, pAS positivity was not found in all five sequential slides in two subjects (P02 and C02), among whom the semiquantitative grade was also 1+. B: Representative figures of multifocally distributed and differently rated nerve plexuses in one patient (P07). Red arrows indicate pAS-positive findings. Calibration bars: figures subtitled Negative, Grade 2+, and Grade 3+ = 50 μm; figure subtitled Grade 1+ = 80 μm. pAS, phosphorylated alpha-synuclein.

In the detailed analysis of 5 slides from the proximal and distal blocks in both the patient and control groups, samples from 6 of 9 subjects with pAS positivity (66.7%) were positive in both proximal and distal blocks (Supplementary Table 1 in the online-only Data Supplement and Figure 1). Moreover, positivity was present in all 5 serial sections in 80.0% of positively stained blocks (12/15); three blocks of P02 and C02 were exceptions.

Regarding the severity of pAS positivity, severe density (3+) was found in both PD and iRBD patients. When the results were discordant between proximal and distal blocks (P06, P08, and C02), only mild density (1+) was found in the positive block. Similarly, when pAS-positive findings were not present in all 5 serial sections (P02 and C02), only mild density (1+) was seen. Finally, there was a severity gradient in the distal block of P01.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that pAS positivity increases with increasing tissue volume examined, which is consistent with previous studies. Beach et al. [2] reported that the pAS positivity rate in the GI tract increased from 11/17 (64.7%) to 14/15 (93.3%) when multiple slides and 80-μm frozen sections were examined in their large-scale autopsy study. Lebouvier et al. [3-5] also reported good results (72%–80%, pAS positivity) using wholemount staining, which involves microdissecting the submucosa from the mucosa in the biopsied colon tissue and mounting and staining the whole submucosa at once. The method allowed us to evaluate a large submucosal tissue volume. This study also showed that mild AS accumulation with the semiquantitative grade 1+ could be inconsistently rated within the proximal and distal sites of one organ and consecutive sections taken from a single site. These findings could be explained by the multifocal distribution of AS accumulation in the GI tract, which has a greater influence on the pathologic evaluation of milder disease stages. Therefore, an extensive volume of large full-depth pathologic specimens is required to achieve the maximal positivity rate, but this is not feasible in clinical practice. These results further support the fundamental limit of biopsies that contain only a small portion of mucosal and submucosal layers from the intestinal wall [1].

There were no definite differences in the distribution and severity between patients with iRBD and PD, although iRBD is a prodromal stage of PD. Previous studies have reported pAS-positive rates of 62.5% and 58.3% in the stomach specimens of patients with iRBD and PD, respectively [1,6]. Several studies have reported that the sensitivity of detecting AS accumulation is higher in patients with iRBD than in PD using specimens from the colon [10], submandibular gland [11], and skin [12]. These results support the notion that AS accumulation in the enteric nervous system precedes the progression of Lewy pathology from the periphery. Therefore, it supports the gut-to-brain progression model presented in Braak’s hypothesis [13].

In contrast, one patient with iRBD (P09) showed no positivity on extensive examination. There should be pathologic changes in the brain because iRBD was confirmed with polysomnography. This result suggests an alternative progression pathway for synucleinopathy that does not follow the gut-to-brain progression model. One study examined AS accumulation in the stomach and vagus nerve from an autopsied series of normal controls, patients with incidental Lewy body disease and patients with PD [14]. There was no AS accumulation in the stomach or vagus nerve in normal elderly subjects in that study, which indicated that AS accumulation in the enteric nervous system was present only in patients who had Lewy pathology in their brain. Therefore, the result questioned the so-called “body-first” origin of synucleinopathy. Recently, a “brain-first” PD hypothesis, in which pathologic AS descends from the brain to the gut, has been suggested based on multimodal imaging data [15,16]. Taken together, this study provides evidence for complexity in the origin and progression of Lewy pathology in synucleinopathy. Another possibility is that some patients with iRBD do not progress to neurodegenerative diseases for a long period of time [17] or develop non-Lewy body diseases, such as multiple system atrophy [18]. Therefore, this patient might have had non-Lewy pathology in the brain.

The negative result of one control subject (C01) whose initial result was positive can be explained by the different definitions of pAS positivity in the previous study [1]. The previous definition of pAS positivity allowed a ‘diffuse staining’ pattern that the initial staining result for this subject showed. Later, we used a more conservative definition [6] based on evidence from subsequent studies [7,8]. The staining results for this subject confirmed that the current definition of pAS positivity used in this study was more reliable than the previous one because there were no positive findings in this subject, including the ‘diffuse staining’ pattern.

In conclusion, examination of a large tissue volume increased the sensitivity of detecting AS accumulation in the GI tract. This study implies a fundamental limit of biopsied tissue and highlights the complexity of pathologic progression of synucleinopathy.

Acknowledgments

The training program of the Systemic Synuclein Sampling Study (S4) was provided courtesy of Prof. Beach.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by research grants from the Seoul National University Hospital (No. 0420170460), Chungnam National University Sejong Hospital (No. 2021-S4-003), and the National Research Foundation of Korea (No. 2018R1D1A1B07041440).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Chaewon Shin, Beomseok Jeon. Data curation: Chaewon Shin, Seong-Ik Kim, Sung-Hye Park. Formal analysis: Chaewon Shin, Seong-Ik Kim, Sung-Hye Park, Jung Hwan Shin, Chan Young Lee, Beomseok Jeon. Funding acquisition: Chaewon Shin, Beomseok Jeon. Investigation: Chaewon Shin, Seong-Ik Kim, Sung-Hye Park. Methodology: Chaewon Shin, Seong-Ik Kim, Sung-Hye Park, Beomseok Jeon. Project administration: Beomseok Jeon. Resources: Chaewon Shin, Seong-Ik Kim, Sung-Hye Park, Jung Hwan Shin, Chan Young Lee, Han-Kwang Yang, Hyuk-Joon Lee, Seong-Ho Kong, Yun-Suhk Suh, Han-Joon Kim. Software: Chaewon Shin, Seong-Ik Kim. Supervision: Sung-Hye Park, Beomseok Jeon. Validation: Sung-Hye Park, Beomseok Jeon. Visualization: Chaewon Shin. Writing—original draft: Chaewon Shin, Han-Joon Kim, Beomseok Jeon. Writing—review & editing: all authors.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.14802/jmd.22042.

Detailed pAS immunostaining results with semi-quantitative grades of extensive tissue (5 slides per block)

REFERENCES

- 1.Shin C, Park SH, Yun JY, Shin JH, Yang HK, Lee HJ, et al. Fundamental limit of alpha-synuclein pathology in gastrointestinal biopsy as a pathologic biomarker of Parkinson’s disease: comparison with surgical specimens. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;44:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Vedders L, Lue L, White Iii CL, et al. Multiorgan distribution of phosphorylated alpha-synuclein histopathology in subjects with Lewy body disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:689–702. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0664-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebouvier T, Chaumette T, Damier P, Coron E, Touchefeu Y, Vrignaud S, et al. Pathological lesions in colonic biopsies during Parkinson’s disease. Gut. 2008;57:1741–1743. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.162503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lebouvier T, Pouclet H, Coron E, Drouard A, N’Guyen JM, Roy M, et al. Colonic neuropathology is independent of olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2011;1:389–394. doi: 10.3233/JPD-2011-11061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebouvier T, Neunlist M, Bruley des Varannes S, Coron E, Drouard A, N’Guyen JM, et al. Colonic biopsies to assess the neuropathology of Parkinson’s disease and its relationship with symptoms. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin C, Park SH, Shin JH, Yun JY, Yang HK, Lee HJ, et al. Gastric synucleinopathy as prodromal pathological biomarker in idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92:450–451. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-324743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beach TG, Corbillé AG, Letournel F, Kordower JH, Kremer T, Munoz DG, et al. Multicenter assessment of immunohistochemical methods for pathological alpha-synuclein in sigmoid colon of autopsied Parkinson’s disease and control subjects. J Parkinsons Dis. 2016;6:761–770. doi: 10.3233/JPD-160888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin C, Park SH, Yun JY, Shin JH, Yang HK, Lee HJ, et al. Alpha-synuclein staining in non-neural structures of the gastrointestinal tract is non-specific in Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2018;55:15–17. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chahine LM, Beach TG, Brumm MC, Adler CH, Coffey CS, Mosovsky S, et al. In vivo distribution of α-synuclein in multiple tissues and biofluids in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2020;95:e1267–e1284. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sprenger FS, Stefanova N, Gelpi E, Seppi K, Navarro-Otano J, Offner F, et al. Enteric nervous system α-synuclein immunoreactivity in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology. 2015;85:1761–1768. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vilas D, Iranzo A, Tolosa E, Aldecoa I, Berenguer J, Vilaseca I, et al. Assessment of α-synuclein in submandibular glands of patients with idiopathic rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:708–718. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Qassabi A, Tsao TS, Racolta A, Kremer T, Cañamero M, Belousov A, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of synuclein pathology in skin in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2021;36:895–904. doi: 10.1002/mds.28399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braak H, de Vos RA, Bohl J, Del Tredici K. Gastric alpha-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner’s and Auerbach’s plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson’s disease-related brain pathology. Neurosci Lett. 2006;396:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Shill HA, Driver-Dunckley E, Mehta SH, et al. Vagus nerve and stomach synucleinopathy in Parkinson’s disease, incidental lewy body disease, and normal elderly subjects: evidence against the “body-first” hypothesis. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11:1833–1843. doi: 10.3233/JPD-212733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horsager J, Andersen KB, Knudsen K, Skjærbæk C, Fedorova TD, Okkels N, et al. Brain-first versus body-first Parkinson’s disease: a multimodal imaging case-control study. Brain. 2020;143:3077–3088. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borghammer P, Van Den Berge N. Brain-first versus gut-first Parkinson’s disease: a hypothesis. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019;9(s2):S281–S295. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fereshtehnejad SM, Yao C, Pelletier A, Montplaisir JY, Gagnon JF, Postuma RB. Evolution of prodromal Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: a prospective study. Brain. 2019;142:2051–2067. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Postuma RB, Pelletier A, Gagnon JF, Montplaisir J. Evolution of prodromal multiple system atrophy from REM sleep behavior disorder: a descriptive study. J Parkinsons Dis. 2022;12:983–991. doi: 10.3233/JPD-213039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed pAS immunostaining results with semi-quantitative grades of extensive tissue (5 slides per block)