Abstract

Neurogenic differentiation 1 (NeuroD1) is an essential transcription factor for neuronal differentiation, maturation, and survival, and is associated with inflammation in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced glial cells; however, the concrete mechanisms are still ambiguous. Therefore, we investigated whether NeuroD1-targeting miRNAs affect inflammation and neuronal apoptosis, as well as the underlying mechanism. First, we confirmed that miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p, which target NeuroD1, reduced NeuroD1 expression in microglia and astrocytes. In LPS-induced microglia, miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, the phosphorylation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and p38, and the expression of cyclooxygenase and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) via the NF-κB pathway. Moreover, miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p inhibited the expression of NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes, NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, and IL-1β, which are involved in the innate immune response. In LPS-induced astrocytes, miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p reduced ERK phosphorylation and iNOS expression via the STAT-3 pathway. Notably, miR-30a-5p exerted greater anti-inflammatory effects than miR-153-3p. Together, these results indicate that miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p inhibit MAPK/NF-κB pathway in microglia as well as ERK/STAT-3 pathway in astrocytes to reduce LPS-induced neuronal apoptosis. This study highlights the importance of NeuroD1 in microglia and astrocytes neuroinflammation and suggests that it can be regulated by miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Glial cells, Inflammation, MicroRNA, NeuroD1

INTRODUCTION

The central nervous system (CNS) comprises numerous cell types, including glia and neuronal cells; in particular, microglia and astrocytes are resting resident immune cells that play important roles in regulating the innate immune system (1). Microglia are primary immune cells that, when activated, initiate phagocytosis and produce numerous pro-inflammatory mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6, in response to pathological triggers (2). These pro-inflammatory mediators can enhance astrocytes activation and amplify neuronal apoptosis (3). Indeed, astrocytes activated by microglia-derived pro-inflammatory mediators release neurotoxins similar to microglia (4). Therefore, abnormal microglia and astrocytes activation increase the inflammatory response, leading to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (5, 6).

Neuronal differentiation factor 1 (NeuroD1) is a basic helix loop helix (bHLH) transcription factor that is involved in the development of the central and peripheral nervous systems (7). It has been suggested that NeuroD1 is essential for neuronal survival and maturation as it is an important transcription factor for neuronal differentiation, development, maturation, and survival, as well as the neuronal reprogramming of other cells (8, 9). Together, these studies suggest that NeuroD1 is a potent neurogenesis differentiation factor that promotes a neuronal fate. Interestingly, recent studies have shown that NeuroD1 is involved in spinal cord injury (SCI) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation (10, 11); however, it remains unclear whether NeuroD1 plays an important role in neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous small, non-coding, single-stranded RNAs composed of around 22 nucleotides that bind to the 3’-untranslated region (UTR) of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and alter post-transcriptional levels by regulating their degradation or translational inhibition, according to the degree of sequence complementarity (12). MiRNAs are involved in various cellular and pathological processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, neuroinflammation, and carcinogenesis (13). About 70% of all miRNAs are expressed in the brain and are closely related to CNS development, neuronal differentiation, adult neurogenesis, and memory formation (14). Since miRNAs can bind to multiple targets and simultaneously affect numerous different signaling pathways, they may be suitable for maintaining brain homeostasis and as potential therapeutic agents in CNS diseases (15).

Inflammasomes are intracellular multiprotein complexes that contain a nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)-like receptors. NLRs are innate cytosolic receptors that recognize diverse pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (16). NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes are the most widely characterized NLR inflammasome complexes as they are related to several human diseases (17). NLRP3 is a component of the NLRP3 inflammasome that recruits the adapter apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain (ASC) and caspase-1 before proceeding to cleave pro-IL-1ꞵ and pro-IL-18 into their mature forms (18). NLRP3 inflammasome activation involves two canonical signals: priming and activation. The first signal (priming) is provided by inflammatory stimuli, such as microbial or endogenous molecules that induce nuclear factor (NF)-κB-mediated NLRP3 and pro-IL-1ꞵ expression. The second signal (activation) is triggered by PAMPs and DAMPs, which promote NLRP3 inflammasome activation and thus caspase-1 mediated IL-1ꞵ and IL-18 secretion (19).

In this study, we hypothesized that NeuroD1 was associated with LPS-induced microglia and astrocytes activation; therefore, we investigated whether NeuroD1 was related to microglia and astrocytes inflammation and neuronal apoptosis, and used miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p targeting NeuroD1 to identify immunoregulatory mechanisms that can regulate inflammation and neuronal apoptosis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

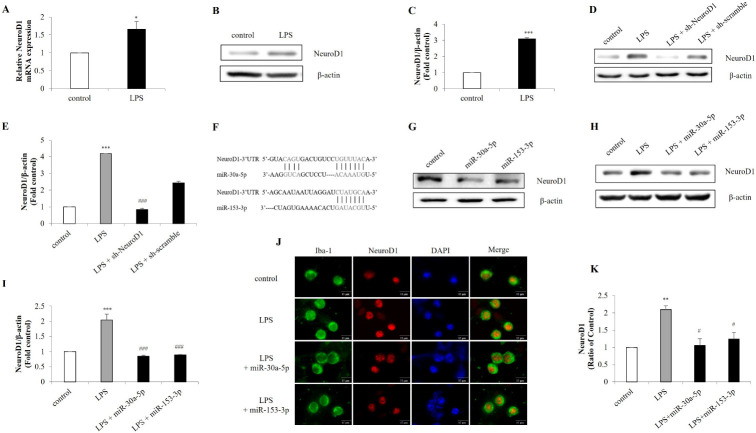

LPS induces NeuroD1 expression, which is reduced by miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p targeting NeuroD1 in microglia

Microglia are immune cells that are activated in response to inflammation, infection, or brain injury (20). Significant responses by LPS stimulation reflect that microglia appear to be the most important factor in neuroinflammation. Therefore, the inhibition of their activation could be a potential treatment for neuronal disease (21, 22). NeuroD1 allow the brain to maintain cellular homeostasis, and may underlie the response to damage (23). Considering the neuronal functions of NeuroD1, we investigated whether LPS treatment would affect NeuroD1 expression in microglia. When BV-2 cells were challenged with LPS, significant increases were observed in the expression of NeuroD1 (Fig. 1A-C). To further validate LPS-induced NeuroD1 expression, NeuroD1 was knocked down by NeuroD1 shRNA. As expected, LPS-induced expression of NeuroD1 was subsequently decreased by NeuroD1 shRNA (Fig. 1D, E). In order to regulate gene expression by ectopic miRNA, we constructed miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p targeting NeuroD1 (Fig. 1F, G), which were transfected into BV-2 cells. Consistent with the NeuroD1 shRNA results, NeuroD1 expression was downregulated by miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p compared to the LPS-treated control group (Fig. 1H, I). It also revealed that miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p reduced NeuroD1 expression in primary microglia (Fig. 1J, K). Taken together, LPS treatment increase NeuroD1 expression in microglia and miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p directly silence NeuroD1 expression in microglia.

Fig. 1.

Expression of NeuroD1 by LPS is targeted by miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p. BV-2 cells were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 1 h. After stimulation, the expression of NeuroD1 was assessed by (A) RT-qPCR and (B, C) western blot. (D, E) BV-2 cells were transfected with NeuroD1 shRNA (1 μg) for 24 h followed by treatment with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 1 h. The protein was extracted and the expression of NeuroD1 was detected by western blot. (F) MiR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p binding site were predicted in the NeuroD1 mRNA. (G) NeuroD1 was knocked down by miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p (50 nM) in microglia cells. Knockdown efficiency was determined by protein levels of NeuroD1. (H, I) BV-2 cells were transfected with miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p followed by LPS (1 μg/ml) treatment for 1 h. (J, K) Primary microglia were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 1 h, and immunofluorescence was conducted to detect NeuroD1 using a Iba-1 as a microglia marker (Scale bars: 15 μm). Data are presented as the means ± S.D. Values of *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus control; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus LPS group.

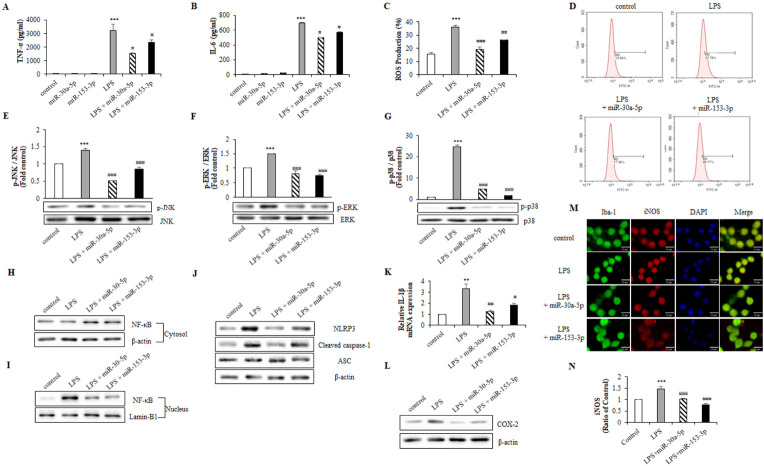

MiR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p regulate neuroinflammation via the MAPK, NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB pathways in LPS-induced BV-2 cells

Innate immune cells express TLR4 that detect PAMPs and DAMPS via which LPS mediates immune activation and the subsequent activation of transcription factors, which trigger the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, inflammatory mediators and ROS in microglia (24, 25). We confirmed the effects of miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p on pro-inflammatory factors in LPS-induced microglia. Interestingly, LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-6 secretion and ROS production were reduced by miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p (Fig. 2A-D). To investigate whether miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p inhibits the production of inflammatory cytokines through MAPK pathway, we examined the effects of on LPS-induced phosphorylation of MAPK in BV-2 cells. LPS increased JNK, ERK, and p38 phosphorylation, whereas miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p markedly inhibited LPS-induced phosphorylation (Fig. 2E-G).

Fig. 2.

MiR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p regulate inflammatory factors through MAPK pathway. BV-2 cells were transfected with miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p (50 nM) for 24 h followed by treatment with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 1 h. (A, B) Cell-free supernatant were collected and TNF-α and IL-6 were evaluated using ELISA. (C, D) LPS-induced ROS was measured through flow cytometry with H2DCF-DA (5 μM) for 1 h. (E-G) The protein was extracted, and the expression of protein level was detected by western blot to measure inflammatory factors p-JNK, p-ERK and p-p38. (H, I) Translocation of NF-κB was detected by western blot. BV-2 cells were lysed to cytosol and nucleic extracts. β-actin and Lamin-B1 were used as an internal control. (J) BV-2 cells were lysed to whole lysates and NLRP3 inflammasome factors, NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1 and ASC. (K) The IL-1β mRNA expression was analyzed by RT-qPCR. (L) Western blot analysis was performed to measure the expression of COX-2 in BV-2 cells. (M, N) Primary microglia cells were transfected with miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p for 24 h followed by treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 1 h. The expression of iNOS was detected by immunofluorescence analysis (Scale bars: 15 μm). Data are presented as the means ± S.D. Values of **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus control; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus LPS group.

The NLRP3 inflammasome complex promotes caspase-1 production to generate IL-18 as well as IL-1β, a major pro-inflammatory cytokine that affects almost every cell type and mediates inflammation in various tissues (16, 26). A recent study noted that LPS activates NLRP3 by priming signals induced by TLRs/NF-κB, resulting in increased NLRP3, pro-IL-1β, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and iNOS expression levels in various immune cell types (27, 28); therefore, we examined the effect of miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p on correlation with NF-κB activation and NLRP3 inflammasome. LPS provoked the translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus, whereas miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p blocked this process (Fig. 2H, I). Likewise, miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p suppressed NLRP3 and cleaved caspase-1 expression, thereby inhibiting IL-1β expression, but did not affect that of ASC (Fig. 2J, K). Furthermore, we found that miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p decreased COX-2 expression in BV-2 cells and iNOS expression in primary microglia (Fig. 2L-N). These results indicate that miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p protects against LPS-induced neuroinflammation through MAPK/NLRP3 inflammasome/NF-κB pathways in microglia.

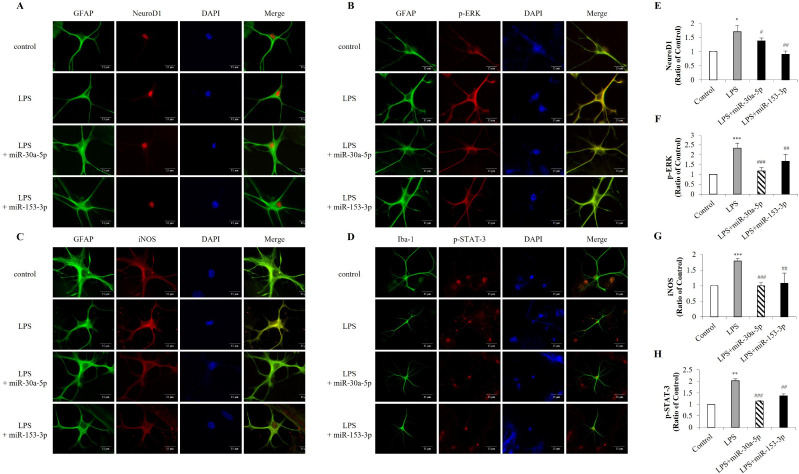

MiR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p suppress LPS-induced ERK phosphorylation and iNOS expression in primary astrocytes

To identify NeuroD1 expressed in astrocytes, we performed immunofluorescent double-staining for NeuroD1 and GFAP, finding that NeuroD1 expression increased in LPS-induced primary astrocytes were inhibited by miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p (Fig. 3A, E). The TLR4-dependent pathway and the transcription factors NF-κB and STAT-3 are associated with iNOS expression, while MAPK pathways have been shown to affect iNOS expression in response to TLR4 activation in astrocytes (29). Therefore, we confirmed the effect of miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p on ERK and STAT-3 phosphorylation and iNOS expression in astrocytes. MiR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p markedly reduced ERK phosphorylation and iNOS expression (Fig. 3B, C, F, G) and decreased LPS-induced p-STAT-3 nuclear translocation in astrocytes (Fig. 3D, H). Overall, these results demonstrate that miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p regulate the ERK/STAT-3 pathway in response to TLR4 activation.

Fig. 3.

Inflammatory mediators are decreased by miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p in astrocytes. Primary astrocytes were transfected with miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p (50 nM) for 24 h followed by treatment with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 24 h. Immunofluorescence was conducted with (A, E) NeuroD1, (B, F) p-ERK, (C, G) iNOS and (D, H) p-STAT-3 with GFAP as an astrocytes marker (Scale bars: 15 μm). Data are presented as the means ± S.D. Values of **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus control; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus LPS group.

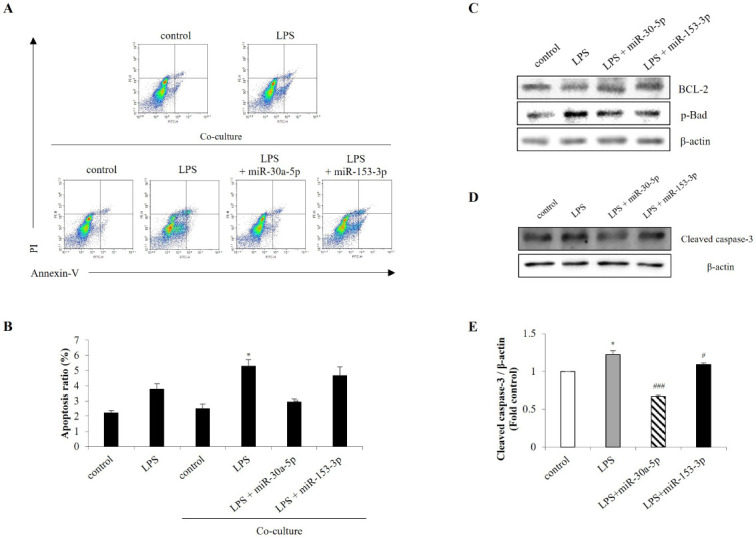

MiR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p expression in microglia relieve neuronal apoptosis

Neurons damaged by disease, injury, or inflammatory insult can release various factors that activate microglia and astrocytes, which subsequently release neurotoxins and damage neurons (30). Therefore, to determine whether NeuroD1 expression in microglia induced apoptosis in neuronal cells, SH-SY5Y cells were co-cultured with miR-30a-5p- and miR-153-3p-transfected BV-2 cells. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that SH-SY5Y apoptosis was significantly suppressed when co-cultured with miR-30-5p- and miR-153-3p-transfected BV-2 cells (Fig. 4A, B). Western blot analysis revealed that miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p increased BCL-2 and decreased p-Bad levels in SH-SY5Y co-cultured with BV-2 (Fig. 4C). Moreover, miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p decreased cleaved-caspase-3 levels compared to LPS-induced primary mixed cells (Fig. 4D, E). Therefore, these results suggest that NeuroD1 inhibition by miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p in microglia affects neuronal apoptosis induced by LPS.

Fig. 4.

MiR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p in microglia cells alleviate neuronal apoptosis. BV-2 cells were transfected with miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p (50 nM) for 24 h. Then BV-2 cells and SH-SY5Y cells were co-cultured followed by treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 1 h in BV-2 cells. (A, B) The Annexin-V/PI images were detected by flow cytometry. (C) Western blot analysis was performed to measure the expression of BCL-2 and p-Bad in SH-SY5Y co-cultured with BV-2 cells. (D, E) Primary mixed cells were transfected with miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p for 24 h followed by LPS (1 μg/ml) for 1 h. Cells were harvested, and the expression protein levels of cleaved caspase-3 was analyzed by western blot. Data are presented as the means ± S.D. Values of *P < 0.05 versus control; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 versus LPS group.

In conclusion, this study confirms that miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p targeting NeuroD1 protect microglia, astrocytes, and neurons against LPS-induced neuroinflammation. There is a limitation in co-culture experiment to describe in-vivo neural networks between neurons and microglia. However, for the first time, we show that NeuroD1-targeting miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p reduce neuronal apoptosis by reducing the inflammatory response. These finding may provide that miR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p are novel regulators that suppresses NeuroD1 expression in LPS-induced microglia and astrocytes inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were provided by Corning (New York, NY, USA). Heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) were purchased from Gibco (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). LPS was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). TNF-α and IL-6 were measured using TNF-α and IL-6 DuoSet ELISA kits (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was measured using H2DCF-DA from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). Antibodies against ERK1/2, p-ERK1/2, p38, p-p38, NF-κB, NLRP3, COX-2, iNOS, rabbit IgG HRP, and mouse IgG HRP were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA); NeuroD1, Iba-1, GFAP, cleaved caspase-3, mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 488), mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 568), mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 488), rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 488) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); and JNK, p-JNK, caspase-1 (p20), ASC, p-STAT-3, β-actin, and Lamin-B1 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA).

Cell culture

BV-2 mouse microglia cells, SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells, and 293T human kidney cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. SH-SY5Y cells were co-cultured with BV-2 cells using a 0.4 μm pore polyester Transwell membrane (Corning). BV-2 cells were cultured in the upper well of the 24-transwell insert and SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in the lower 24-well plate.

Mouse primary cell culture

Primary mixed cultures were obtained from the hippocampus of three-day-old newborn ICR mouse pups (Koatech, Pyeongtaek, Korea). Briefly, whole brain was dissected out after removing the skull. After stripping the meninges, the hippocampus and cortex were dissected. Dissociated mixed cells were immediately transferred into poly-D-lysine-coated T75 flasks and incubated in DMEM containing 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) in a CO2 incubator. The media was changed every 5 days until day 15. The authors confirmed that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experiments were conducted under the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in Konyang University.

Plasmids and transfection

Lentiviral GFP vectors containing NeuroD1 shRNA or scrambled shRNA were purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD, USA). MiR-30a-5p and miR-153-3p mimics were synthesized by Genolution (Seoul, Korea). 293T cells were co-transfected with NeuroD1 shRNA, scrambled shRNA, and miRNAs and packing plasmids using Lentiviral packaging kit (Origene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h and 72 h of transfection, culture supernatants containing lentiviral particles were harvested. Then, BV-2 cells and primary cells were infected with the harvested lentiviral particles.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The levels of the cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 were measured using ELISA kits, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cultured cell supernatants were collected and TNF-α and IL-6 levels were evaluated by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). The concentration of each cytokine was calculated using the standard value obtained from a linear regression equation.

Flow cytometry ROS detection

ROS were measured in SH-SY5Y cells co-cultured with BV-2 cells. Briefly, the cells were treated with H2DCF-DA for 1 h, harvested with PBS, and ROS levels were analyzed using flow cytometry (NOVOCYTE flow cytometer, ACEA Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using Novoexpress software (ACEA Biosciences).

Western blot analysis

The protein samples used for western blot analysis were lysed using RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Thermo Scientific). Protein extracts were separated using 10-12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) which were incubated with 5% BSA and primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Next, the membranes were incubated for 1 h with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Protein bands on the membrane were developed using chemiluminescent ECL reagent (Enzynomics, Daejeon, South Korea) with an ECL detection system (Vilber Lourmat, Paris, France).

Immunofluorescence analysis

After cells had been cultured on coverslips overnight, they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 at 22°C for 10 min, and blocked by incubating the cells with 1% BSA and 22.52 mg/ml glycine in 0.1% PBST solution for 1 h at room temperature. Next, cells were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C and then with corresponding secondary antibodies at 22°C for 1 h. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, mounted on a coverslip, and then observed using a Zeiss fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, BW, Germany).

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

RNA was extracted from lysed BV-2 cells using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then quantified using a NanoDropTM One (Thermo Fisher). cDNA was synthesized using DiaStarTM 2X RT Pre-Mix (Biofact, Daejeon, Korea) and RT-qPCR was conducted using a CFX96TM real-time system (Bio-Rad) with SsoAdvancedTM Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Biofact) and the following primers: NeuroD1 (forward: 5’-CAA AGC CAC GGA TCA ATC TT-3’, reverse: 5’-CCC GGG AAT AGT GAA ACT GA-3’), IL-1β (forward: 5’-ATG CCA CCT TTT GAC AGT GAT G-3’, reverse: 5’ TGT GCT GCT GCG AGA TTT GA-3’), and GAPDH (forward: 5’-TCA CCA CCA TGG AGA AGG C-3’, reverse: 5’-GCT AAG CAG TTG GTG GTG CA-3’). Target gene expression was analyzed using the Ct method.

Flow cytometry apoptosis measurement

To confirm the effect of NeuroD1 on apoptosis in microglial cells, we detected apoptosis using an Alexa Fluor® 488 Annexin V/Dead Cell Apoptosis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). SH-SY5Y cells were co-cultured in a Transwell plate with BV-2 cells that had been exposed to LPS (1 μg/ml) for 1 h. After LPS stimulation, SH-SY5Y cells were washed and harvested with PBS before being resuspended in 100 μL Annexin-binding buffer containing FITC Annexin V (5 μl) and 100 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI) solution (1 μl) for 15 min in the dark at 22°C. After incubation, 400 μl Annexin-binding buffer was added to each sample before flow cytometry (NOVOCYTE flow cytometer, ACEA Biosciences). Data were analyzed using Novoexpress software (ACEA Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard error and represent the average of three independent experiments. The SPSS statistical software package (Version 18.0, NY, USA) was used for one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2018R1A2B6001743 and 2021R1F1A1051920).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

References

- 1.Ransohoff RM, Brown MA. Innate immunity in the central nervous system. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1164–1171. doi: 10.1172/JCI58644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reemst K, Noctor SC, Lucassen PJ, Hol EM. The indispensable roles of microglia and astrocytes during brain development. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:566. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang P, Lokuta KM, Turner DE, Liu B. Synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity of manganese and lipopolysaccharide: differential involvement of microglia and astroglia. J Neurochem. 2010;112:434–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha MK, Lee WH, Suk K. Functional polarization of neuroglia: implications in neuroinflammation and neurological disorders. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;103:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S, Colonna M. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease: a target for immunotherapy. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;106:219–227. doi: 10.1002/JLB.MR0818-319R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosley RL, Benner EJ, Kadiu I, et al. Neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Clin Neurosci Res. 2006;6:261–281. doi: 10.1016/j.cnr.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, Zhang B, Xu S, Lin R, Wang W. Lentivirus carrying the NeuroD1 gene promotes the conversion from glial cells into neurons in a spinal cord injury model. Brain Res Bull. 2017;135:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo Z, Zhang L, Wu Z, Chen Y, Wang F, Chen G. In vivo direct reprogramming of reactive glial cells into functional neurons after brain injury and in an Alzheimer's disease model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:188–202. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwab MH, Bartholomae A, Heimrich B, et al. Neuronal basic helix-loop-helix proteins (NEX and BETA2/Neuro D) regulate terminal granule cell differentiation in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3714–3724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03714.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu X, Shen Y, Wang W, Li X. MiR‐30a‐5p ameliorates spinal cord injury‐induced inflammatory responses and oxidative stress by targeting Neurod 1 through MAPK/ERK signalling. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2018;45:68–74. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao F, Lei J, Zhang Z, Yang Y, You H. Curcumin alleviates LPS-induced inflammation and oxidative stress in mouse microglial BV2 cells by targeting miR-137-3p/NeuroD1. RSC Adv. 2019;9:38397–38406. doi: 10.1039/C9RA07266G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu S, Jin L, Zhang F, Sarnow P, Kay MA. Biological basis for restriction of microRNA targets to the 3' untranslated region in mammalian mRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:144. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi Z, Zhou H, Lu L, et al. The roles of microRNAs in spinal cord injury. Int J Neurosci. 2017;127:1104–1115. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2017.1323208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Y, Hong W, Wang X, et al. MicroRNAs in microglia: how do microRNAs affect activation, inflammation, polarization of microglia and mediate the interaction between microglia and glioma? Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:125. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jo EK, Kim JK, Shin DM, Sasakawa C. Molecular mechanisms regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:148–159. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim EA, Hwang K, Kim JE, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of N-cyclooctyl-5-methylthiazol-2-amine hydrobromide on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response through attenuation of NLRP3 activation in microglial cells. BMB Rep. 2021;54:557–562. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2021.54.11.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JPY. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:707–735. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He Y, Hara H, Núñez G. Mechanism and regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jha MK, Jo M, Kim JH, Suk K. Microglia-astrocyte crosstalk: an intimate molecular conversation. The Neuroscientist. 2019;25:227–240. doi: 10.1177/1073858418783959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim YS, Kim SS, Cho JJ, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-3: a novel signaling proteinase from apoptotic neuronal cells that activates microglia. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3701–3711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4346-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodea LG, Wang Y, Linnartz-Gerlach B, et al. Neurodegeneration by activation of the microglial complement-phagosome pathway. J Neurosci. 2014;34:8546–8556. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5002-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao Z, Ure K, Ables JL, et al. Neurod1 is essential for the survival and maturation of adult-born neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1090–1092. doi: 10.1038/nn.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenhill CJ, Rose-John S, Lissilaa R, et al. IL-6 trans-signaling modulates TLR4-dependent inflammatory responses via STAT3. J Immunol. 2011;186:1199–1208. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryu KY, Lee Hj, Woo H, et al. Dasatinib regulates LPS-induced microglial and astrocytic neuroinflammatory responses by inhibiting AKT/STAT3 signaling. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16:1–36. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1561-x.67b015539a3c48b8ab02fdf49f370541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Mechanisms and functions of inflammasomes. Cell. 2014;157:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, et al. Cutting edge: NF-κB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol. 2009;183:787–791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia Q, Hu Q, Wang H, et al. Induction of COX-2-PGE2 synthesis by activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway contributes to neuronal death triggered by TDP-43-depleted microglia. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1702–e1702. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hung CC, Lin CH, Chang H, et al. Astrocytic GAP43 induced by the TLR4/NF-κB/STAT3 axis attenuates astrogliosis-mediated microglial activation and neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2016;36:2027–2043. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3457-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartmann K, Sepulveda-Falla D, Rose IV, et al. Complement 3+-astrocytes are highly abundant in prion diseases, but their abolishment led to an accelerated disease course and early dysregulation of microglia. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s40478-019-0735-1.a08887f6a7ab410092e18ec3fc60b63a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]