Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus can utilize several hydroxamate siderophores for growth under iron-restricted conditions. Previous findings have shown that S. aureus possesses a cytoplasmic membrane-associated traffic ATPase that is involved in the specific transport of iron(III)-hydroxamate complexes. In this study, we have identified two additional genes, termed fhuD1 and fhuD2, whose products are involved in this transport process in S. aureus. We have shown that fhuD2 codes for a posttranslationally modified lipoprotein that is anchored in the cytoplasmic membrane, while the deduced amino acid sequence predicts the same for fhuD1. The predicted FhuD1 and FhuD2 proteins share 41.0% identity and 56.4% total similarity with each other, 45.9 and 49.1% total similarity with the FhuD homolog in Bacillus subtilis, and 29.3 and 24.6% total similarity with the periplasmic FhuD protein from Escherichia coli. Insertional inactivation and gene replacement of both genes showed that while FhuD2 is involved in the transport of iron(III) in complex with ferrichrome, ferrioxamine B, aerobactin, and coprogen, FhuD1 shows a more limited substrate range, capable of only iron(III)-ferrichrome and iron(III)-ferrioxamine B transport in S. aureus. Nucleotide sequences present upstream of both fhuD1 and fhuD2 predict the presence of consensus Fur binding sequences. In agreement, transcription of both genes was negatively regulated by exogenous iron levels through the activity of the S. aureus Fur protein.

Iron is an element that is required by virtually all bacteria, participating in such vital functions as electron transport and DNA synthesis (11). However, the requirement for this element puts significant constraints on bacteria due to its tendency to oxidize and precipitate at a neutral pH in aerobic environments, making it biologically unavailable (27). To counter this, many microorganisms produce high-affinity iron(III)-chelating molecules, termed siderophores, that serve to solubilize iron(III) and present it to the bacterial surface, where the complex may be transported across the bacterial envelope so that the iron can be used for biological processes (12). A common group of siderophores chelate iron using hydroxamate residues and are, not surprisingly, generally referred to as hydroxamate siderophores (1). Examples of hydroxamate siderophores include ferrichrome, ferrioxamine B, coprogen, aerobactin, and rhodotorulic acid, among others.

Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition in gram-negative bacteria has been extensively studied, but, to date, there is comparatively little information available regarding high-affinity iron transport in gram-positive bacteria and, in particular, the staphylococci. Although not able to produce hydroxamate siderophores, Staphylococcus aureus is nonetheless able to utilize them for enhanced growth under conditions of iron limitation (26). Indeed, the fhuCBG operon was shown to be necessary for the utilization of hydroxamate siderophores in S. aureus (26). An unusual feature of the fhuCBG operon is that it is predicted to encode only the membrane-spanning and ATPase components of a classical traffic ATPase (3) but lacks a gene that would be predicted to code for a receptor, or solute binding protein, that would bind the iron(III)-siderophore complex with high affinity and transfer it to the membrane-bound permease. This receptor, a soluble periplasmic protein in gram-negative bacteria, is thought to take the form of a membrane-bound lipoprotein in gram-positive bacteria. Indeed, two iron-regulated operons, sirABC (14) and sstABCD (22), whose predicted products share significant homology with iron(III)-siderophore transport components in gram-negative bacteria, have been identified in S. aureus. Moreover, these loci encode proteins (SirA and SstD) that are posttranslationally acylated. Further evidence for lipoproteins serving as iron(III)-siderophore receptors in gram-positive bacteria comes from studies with Bacillus subtilis, where a lipoprotein (designated FhuD and homologous to periplasmic FhuD in Escherichia coli) was shown to be involved in iron(III)-hydroxamate uptake in this organism (25). Based on these observations, we were interested to determine if this scenario holds true for iron(III)-hydroxamate uptake in S. aureus and began investigations to identify a potential lipoprotein that might be involved in this transport system.

Herein, we report the identification and characterization of two S. aureus genes, fhuD1 and fhuD2, and provide evidence that these genes are involved in the transport of iron(III)-hydroxamate complexes but possess different specificities for the various hydroxamate siderophores tested. Predicted amino acid sequence data indicate that both FhuD1 and FhuD2 possess classical lipoprotein signal sequences. In agreement with these findings, we present evidence that FhuD2 is anchored within the cell membrane. We further show that extracellular iron levels regulate transcription of both the fhuD1 and fhuD2 genes via the negative repressor protein, Fur.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids that were used in this study are listed in Table 1. Unless otherwise specified, E. coli and S. aureus were routinely cultivated in Luria-Bertani broth (Difco) and tryptic soy broth (Difco), respectively. Solid media were obtained by the addition of 1.5% (wt/vol) Bacto agar (Difco). Tris-minimal succinate (TMS) was the iron-deficient medium of choice (26). FeC13 (50 μM) was added to TMS media as required. Where appropriate, tetracycline (2 μg/ml), erythromycin (5 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml), and lincomycin (20 μg/ml) were incorporated into media for the cultivation of S. aureus, whereas tetracycline (10 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), erythromycin (300 μg/ml), and kanamycin (30 μg/ml) were incorporated into media for the growth of E. coli. Unless otherwise stated, growth of bacterial cultures was performed at 37°C. Iron-free water was used for all experiments and was obtained by passage through a Milli-Q water filtration system (Millipore Corp).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source of reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. aureus | ||

| RN2564 | (80α) Ω25[Tn551]pig-131 | J. Iandolo |

| RN4220 | rK− mK+ | 17 |

| RN6390 | Prophage-cured wild-type strain | 23 |

| H295 | RN6390 fur::Km Kmr | 26 |

| H364 | RN6390 fhuD2::Tet Tetr | This study |

| H430 | RN6390 fhuD1::Km Kmr | This study |

| H431 | RN6390 fhuD1::Km fhuD2::Tet Kmr Tetr | This study |

| H463 | RN6390 fhuD1-lacZ fhuD1+ Emr Lcr | This study |

| H466 | RN6390 fhuD2-lacZ fhuD2+ Emr Lcr | This study |

| H464 | H295 fhuD1-lacZ fhuD1+ Kmr Emr Lcr | This study |

| H467 | H295 fhuD2-lacZ fhuD2+ Kmr Emr Lcr | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | φ80dlacZΔM15 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17(rK−mK+) supE44 relA1 deoR Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 | Promega |

| ER2566 | F− λ−fhuA2 [lon] ompT lacZ::T7 geneI gal sulA11 Δ(mcrC-mrr)114::IS10 R(mcr-73::miniTn10)2 R(zgb-210::Tn10)1 (Tets) endA1 [dcm] | New England Biolabs |

| Plasmids | ||

| pACYC184 | 4.2-kb E. coli cloning vector; CmrTetr | New England Biolabs |

| pBC SK(+) | Multicopy phagemid cloning vector derived from pUC19; Cmr | Stratagene |

| pDG782 | pMTL22 derivative that carries a kanamycin resistance cassette; Apr Kmr | 13 |

| pDG1513 | pMTL22 derivative that carries a tetracycline resistance cassette; Apr Tetr | 13 |

| pAUL-A | Temperature-sensitive E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector, Emr Lcr | 7 |

| pAW9 | 2.5-kb S. aureus suicide vector; Tetr | 30 |

| pLI50 | 5.2-kb E. coli-S aureus shuttle vector; Apr Cmr | 21 |

| pGEX-2T | 4.9-kb E. coli expression vector; Apr | Amersham |

| pMUTIN4 | Promoterless transcriptional lacZ fusion vector; Apr (E. coli) Emr (S. aureus) | 29 |

| pMTS22 | pBC SK(+) derivative carrying a 1.7-kb PCR fragment, cloned into the BamHI site, that contains fhud1; Cmr | This study |

| pMTS23 | pACYC184 derivative carrying a 1.3-kb PCR fragment, cloned into the EcoRV site, that contains fhud2; Tets Cmr | This study |

| pMTS24 | pMTS23 derivative that contains a 2.1-kb Tet cassette, derived from pDG1513 as a blunt-ended ClaI fragment, cloned into the unique MunI site (blunt-ended) present in fhuD2; Tetr Cmr | This study |

| pMTS28 | pAUL-A derivative carrying a 3.7-kb BamHI fragment, derived from pMTS24, that contains fhuD2::Tet; Emr Tetr | This study |

| pMTS30 | pACYC184 derivative carrying a 1.7-kb PCR fragment, cloned into the blunt-ended SfcI site, that contains fhuD1; Tets Cmr | This study |

| pMTS32 | pMTS30 derivative that contains a 1.5-kb Km cassette, derived from pDG782 as a Stu/SmaI fragment, cloned into the unique SfcI site (blunt-ended) present in fhuD1; Cmr Kmr | This study |

| pMTS33 | pGEX-2T derivative that was digested with BamHI and EcoRI and carries the fhuD2 gene, minus the predicted signal peptide sequence; Apr | This study |

| pMTS35 | pAW9 derivative carrying a 3.2-kb BamHI fragment, derived from pMTS32, that contains fhuD1::Km; Tetr Kmr | This study |

| pTOM1 | pACYC184 derivative carrying a 2.4-kb PCR fragment that contains fhuD2 cloned into the EcoRV site; Tets Cmr | This study |

| pMTS37 | pLI50 derivative carrying a 2.4-kb BamHI/XbaI fragment, derived from pTOM1, that contains the fhuD2 gene; Apr Cmr | This study |

| pMTS40 | pLI50 derivative carrying a 1.7-kb HindIII/XbaI fragment, derived from pMTS22, that contains the fhuD1 gene; Apr Cmr | This study |

| pMTS44 | pMUTIN4 derivative carrying a 618-bp HindIII/BamHI-digested PCR product, that contains the 5′ region of the fhuD1 gene and upstream sequence; Apr Emr | This study |

| pMTS47 | pMUTIN4 derivative carrying a 1.2-kb PCR product that contains the 5′ region of the fhuD2 gene and upstream sequence in the BamHI (Klenow-treated) site; Apr Emr | This study |

Apr, Cmr, Emr, Kmr, Lcr, and Tetr, resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, kanamycin, lincomycin, and tetracycline, respectively.

Recombinant DNA methodology.

Routine DNA methods were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (24). Restriction endonucleases and DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from Life Technologies, Inc. (Burlington, Ontario, Canada), New England Biolabs (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), Roche Diagnostics (Laval, Quebec, Canada), and MBI Fermentas (Flamborough, Ontario, Canada). Plasmid DNA was isolated using QIAprep plasmid spin columns (Qiagen Inc., Santa Clarita, Calif.) as described by the manufacturer. For isolation of staphylococcal plasmid DNA, lysostaphin (50 μg/ml) was incorporated into buffer P1. All PCRs were performed using PwoI polymerase (Roche Diagnostics).

Construction of a fhuD1 mutant.

The S. aureus fhuD1 gene was amplified on a 1.7-kb PCR product that was cloned as a blunt-ended fragment into the SfcI (Klenow-treated) site of pACYC184. The fhuD1 coding region was then disrupted by the insertion of a 1.5-kb kanamycin resistance cassette (obtained as a StuI/SmaI fragment from pDG782) into the unique SfcI site (Klenow treated) within fhuD1. A 3.2-kb BamHI fragment carrying the disrupted fhuD1 gene was then cloned into the unique BamHI site of pAW9 to generate pMTS35. Plasmid pMTS35 was electroporated into RN4220, and colonies showing resistance to kanamycin and tetracycline were selected. Phage 80α was used to transduce the Kmr marker into RN6390, and Kmr Tets colonies were selected for further study. Confirmation of insertion of the Kmr marker into the fhuD1 gene was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis, and the resulting mutant strain was designated H430.

Construction of a fhuD2 mutant.

The S. aureus fhuD2 gene was amplified on a 1.3-kb PCR product and cloned into the EcoRV site of pACYC184. The fhuD2 coding region was disrupted by the insertion of a tetracycline resistance cassette, obtained from plasmid pDG1513 as a 2.1-kb ClaI fragment (Klenow treated), into the unique MunI site (Klenow treated) present within the fhuD2 coding region. A 3.7-kb BamHI fragment containing the disrupted fhuD2 gene was cloned into the unique BamHI site in pAUL-A. The resulting plasmid, designated pMTS28, was introduced into RN4220 by electroporation, and Emr Tcr transformants were selected after growth at 30°C on appropriate antibiotics. Ems Tcr derivatives were obtained following growth at 42°C. Following confirmation by PCR and Southern blotting, the fhuD2 mutation was transduced into RN6390 to produce strain H364.

Construction of a fhuD1 fhuD2 double mutant.

A transducing lysate from strain H364 was used to mobilize the disrupted fhuD2 gene into strain H430. The newly generated fhuD1::Km fhuD2::Tet strain was designated H431.

Siderophore plate bioassay.

Siderophore plate bioassays were performed as described previously (26).

Siderophores.

Ferrichrome and rhodotorulic acid were purchased from Sigma (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), and ferrioxamine B (Desferal; Novartis) was obtained from the London Health Sciences Centre. Aerobactin was a gift from T. Viswanatha (University of Waterloo), and coprogen and alcaligin were gifts from A. Stintzi (Oklahoma State University). Enterobactin was prepared as previously described (31), as was the siderophore(s) from culture supernatants of S. aureus (26).

Construction of lacZ reporter gene fusions. (i) fhuD1-lacZ.

The fhuD1-lacZ fusion was constructed by PCR amplification of a 618-bp DNA fragment encompassing the 5′ end of the fhuD1 coding region. The PCR product was cloned as a HindIII/BamHI fragment into the unique HindIII/BamHI sites of pMUTIN4. The resulting plasmid, pMTS44, was confirmed to contain the fhuD1 promoter region directly upstream of, and in the same orientation as, the vector-borne lacZ gene, thus creating a transcriptional fusion.

(ii) fhuD2-lacZ.

The fhuD2-lacZ fusion was constructed by PCR amplification of a 1,233-bp fragment encompassing the 5′ end of the fhuD2 coding region. The PCR product was cloned into the BamHI (Klenow-treated) site of pMUTIN4, generating plasmid pMTS47. The resulting plasmid, pMTS47, was confirmed to contain the fhuD2 promoter region directly upstream of, and in the same orientation as, the vector-borne lacZ gene to create a transcriptional fusion.

Integration of lacZ fusions into the S. aureus chromosome.

LacZ fusion plasmids were recovered from E. coli and introduced into S. aureus RN4220 by electroporation. Integration of plasmid into the chromosome was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. Phage transduction, using 80α, was utilized to transfer fusions into various S. aureus backgrounds (see Table 1 for strain derivations).

β-Galactosidase expression analysis.

LacZ expression was examined by growing strains of interest on TMS agar under iron-rich (containing 50 μM FeCl3) or iron-poor (containing 1 μM EDDHA [ethylenediamine-di(o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid)]) conditions. Plates were then sprayed with freshly prepared 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-galactoside (MUG) (10 mg/ml), incubated for 15 min at 22°C, and then examined under ultraviolet light (366 nm).

Generation of a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-FhuD2 fusion protein for overexpression.

The fhuD2 gene, minus the predicted signal sequence, was PCR amplified on a 1.1-kb DNA fragment that was then cloned into BamHI/EcoRI-digested pGEX-2T (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The resulting plasmid, pMTS33, was introduced into E. coli strain ER2566 for protein overexpression.

Overexpression and purification of GST-FhuD2.

E. coli ER2566 containing pMTS33 was grown to an A600 of approximately of 0.8. Following the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (0.4 mM), growth was allowed to continue for 3 h before the cells were lysed and the supernatants were passed across a 5-ml GSTrap column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for purification. The purity of the recombinant protein was determined to be in excess of 99%. The apparent molecular mass of the fusion protein in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), 58kDa, was in agreement with that predicted by the amino acid sequence (58.4 kDa).

Generation of antisera.

Polyclonal antisera to GST-FhuD2 were generated in two New Zealand White rabbits (Charles River, Wilmington, Mass.). Briefly, 100 μg of protein in TitreMax Gold adjuvant (CytRx, Norcross, Ga.) was injected subcutaneously into each rabbit. The rabbits were given boosters of 50 μg of protein at 2 and 4 weeks, and at 5 weeks, the rabbits were sacrificed and antisera were collected. The sera were diluted 1:20 before being adsorbed three times over induced ER2566(pGEX-2T) cell lysates immobilized on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. As a negative control, serum was taken from a preimmune bleed of each rabbit.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

SDS-PAGE was performed as previously described (20). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and washing and detection were performed using the ECL Plus chemiluminescent system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) per the manufacturer's instructions. GST-FhuD2 and native FhuD2 were detected by incubating membranes for 2 h at room temperature in adsorbed FhuD2-specific rabbit antisera diluted 1:10,000 in 5% skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline.

Detergent extraction and phase partitioning.

Late-log-phase cultures of S. aureus were harvested by centrifugation after equilibration to an A600 of 1.0, washed three times with sterile saline (NaCl; 0.9%, wt/vol), and resuspended in 100 μl of sterile saline. Cells were lysed by incubation at 37°C with 50 μg of lysostaphin, followed by sonication. Triton X-114 phase partitioning was performed essentially as described previously (4, 9). Detergent pellets were diluted 1:1 with water before sample buffer was added prior to electrophoresis on SDS-polyacrylamide gels.

Computer analysis.

DNA sequence analysis, oligonucleotide primer design, and sequence alignments were performed using the Vector NTI Suite 6 software package (Informax, Inc., Bethesda, Md.). Pairwise alignments were performed using a GAP opening penalty of 10 and a GAP extension penalty of 0.1.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of fhuD1 and fhuD2 described in this communication are registered in the GenBank database under accession numbers AF325854 and AF325855, respectively.

RESULTS

Identification and characterization of two fhuD homologs in S. aureus.

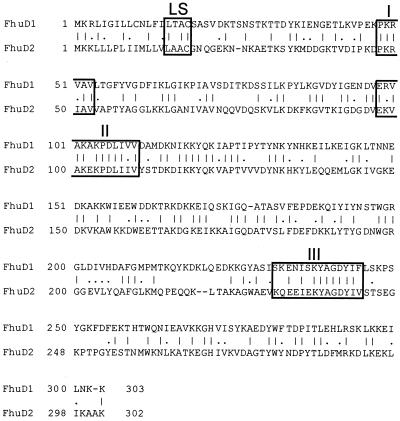

Our previous studies described an operon consisting of three genes, fhuCBG, encoding a membrane-localized traffic ATPase involved in the transport of iron(III)-hydroxamates in S. aureus (26). Transport of iron(III)-hydroxamate complexes in B. subtilis has been shown to involve a lipoprotein, termed FhuD, encoded by one of two divergently transcribed genetic loci on the B. subtilis chromosome (25). Based on these observations, we hypothesized that iron(III)-hydroxamate uptake in S. aureus would similarly require the activity of a lipoprotein and undertook a search of the ongoing S. aureus genome sequences (http://www.genome.ou.edu/staph.html) for open reading frames (ORFs) whose predicted translations showed homology to the B. subtilis FhuD protein. Two potential ORFs, designated fhuD1 and fhuD2, were identified whose products showed sufficient similarity to B. subtilis FhuD to warrant further study. fhuD1 and fhuD2 exist as independent transcriptional units in the S. aureus genome and do not lie in proximity to the fhuCBG operon. Indeed, in the recently completed genome sequence of S. aureus Mu50, which contains in excess of 2,500 ORFs, fhuD1 is ORF SAV0789, fhuD2 is ORF SAV02269, and fhuCBG are ORFs SAV0634, SAV0635, and SAV0636, respectively (19). fhuD1 is a 909-bp element that is predicted to code for a protein of 303 amino acids and 34.8 kDa (Fig. 1). fhuD2 is a 906-bp element that is predicted to encode a protein of 302 amino acids and 34.0 kDa (Fig. 1). FhuD1 and FhuD2 share 41.0% identity and 56.4% total similarity with each other (Fig. 1), while they share 33.3 and 35.6% identity with B. subtilis FhuD. The S. aureus FhuD1 and FhuD2 proteins share only 16.6 and 11.8% identity with the E. coli FhuD protein, respectively. As further support of their role in iron(III)-siderophore transport, both FhuD1 and FhuD2 possess conserved motifs I, II, and III, which are present in a variety of iron(III)-siderophore binding proteins (Fig. 1) (5).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of S. aureus FhuD1 and FhuD2. LS identifies the prelipoprotein signal peptide sequence identified in both FhuD1 and FhuD2. Boxes I, II, and III identify conserved regions present in binding proteins related to siderophore and heme transport in bacteria (5).

fhuD1 and fhuD2 are expressed under conditions of iron limitation.

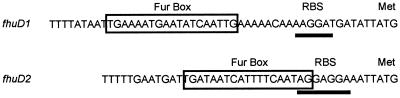

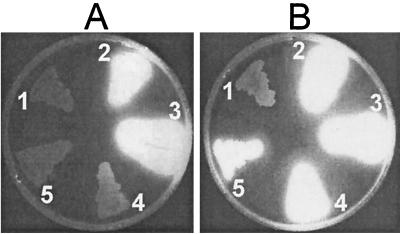

Examination of the sequences upstream of both the fhuD1 and fhuD2 coding regions revealed the presence of Fur binding sites (Fur boxes) (Fig. 2). Fur box consensus sequences in S. aureus were recently identified by Horsburgh et al. (16), and sequences identified in Fig. 2 conform to their observations. The predicted Fur box for fhuD1 spans nucleotides −39 to −21, while that for fhuD2 spans nucleotides −28 to −10. Presumably, then, both fhuD1 and fhuD2 are under the transcriptional control of the Fur repressor protein. To examine the regulation of the S. aureus fhuD genes further, transcriptional fusions were constructed between both fhuD1 and fhuD2 and lacZ on the S. aureus chromosome. The resulting strains H463 (fhuD1-lacZ) and H466 (fhuD2-lacZ) were examined for LacZ expression under iron-replete (Fig. 3A) and iron-limiting (Fig. 3B) growth conditions. H463 and H466 showed no fluorescence in the MUG β-galactosidase assay after growth on iron-replete media, whereas they showed an intense fluorescence when grown on iron-limiting media (compare sectors 4 and 5 in Fig. 3A with those in 3B). As shown in Fig. 4A and B, sectors 2 and 3, β-galactosidase activity was high in H464 (RN6390 fur::Km fhuD1-lacZ) and H467 (RN6390 fur::Km fhuD2::lacZ) when grown under both iron-limited and iron-replete conditions, indicating that both fhuD1 and fhuD2 are under the transcriptional control of Fur. These observations are in agreement with the presence of Fur box sequences upstream of both genes (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Promoter regions of the fhuD1 and fhuD2 genes indicating potential Fur binding sites. Fur box sequences are boxed, putative ribosome binding sites (RBS) are underlined, and the start methionine for the FhuD1 and FhuD2 proteins is indicated above the nucleotide sequence.

FIG. 3.

β-Galactosidase expression by S. aureus grown on iron-rich medium (A) or iron-limited medium (B). β-Galactosidase expression was detected by spraying of agar plates containing pregrown bacteria with MUG and subsequent illumination under ultraviolet light. Bacterial strains on the plates are as follows: 1, RN6390; 2, H464; 3, H467; 4, H463; 5, H466.

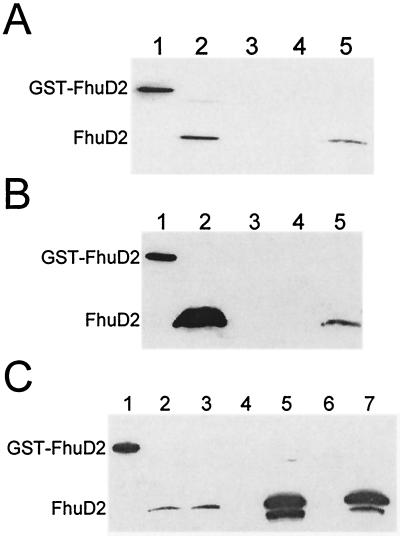

FIG. 4.

Analysis of FhuD2 expression in S. aureus. FhuD2 expression was detected in Western blots using rabbit polyclonal sera raised against purified GST-FhuD2 protein. (A) Immunoblot of fractionated proteins from whole-cell lysates of iron-limited RN6390 by phase partitioning with Triton X-114. Lane 1, 150 ng of purified GST-FhuD2 protein; lane 2, whole-cell lysate; lane 3, Triton X-114-insoluble fraction; lane 4, aqueous fraction; lane 5, detergent fraction. (B) Immunoblot of detergent fractions from Triton X-114 phase-partitioned S. aureus grown in the presence of various concentrations of iron. Lane 1, 150 ng of purified GST-FhuD2 protein; lane 2, H295 grown in TMS medium containing 50 μM FeCl3. Samples loaded in lanes 3 through 5 are from RN6390 grown in TMS medium containing 50 μM FeCl3, 10 μM FeCl3, and 1 μM EDDHA, respectively. (C) Immunoblot of detergent fractions from Triton X-114 phase-partitioned S. aureus grown under iron limitation. Lane 1, 150 ng of purified GST-FhuD2; lane 2, RN6390; lane 3, H430; lane 4, H364; lane 5, H364(pMTS37); lane 6, H431; lane 7, H431(pMTS37).

Evidence for posttranslational modification of FhuD2.

The amino acid sequences of both FhuD1 and FhuD2 contain typical prolipoprotein signal peptides with predicted cleavage sites of 15LTAC18 for FhuD1 and 15LAAC18 for FhuD2 (Fig. 1). Each of these prolipoprotein signal sequences conforms to the consensus sequence for prolipoprotein modification and processing enzymes (6). Immunoblot analysis, using rabbit polyclonal antiserum generated against GST-FhuD2, of cell lysates of iron-starved S. aureus RN6390 revealed a single reactive band with an apparent molecular mass of approximately 34 kDa (Fig. 4A, lane 2), in agreement with that predicted from the amino acid sequence of FhuD2. Phase partitioning of Triton X-114-solubilized cell lysates revealed that FhuD2 was found predominately in the detergent phase (Fig. 4A). Immunoblots incubated in the presence of preimmune sera showed no reactivity (data not shown). Although the majority of FhuD2 is predicted to be hydrophilic, our results suggest that the predicted signal peptidase II cleavage site at cysteine 18 was acylated in S. aureus, thus rendering the protein amphipathic. This is in agreement with observations made for other staphylococcal lipoproteins (14, 22). Although we have no direct evidence at this point that FhuD1 undergoes similar posttranslational modification, we expect this to be the case, given the presence of the prolipoprotein signal peptide (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 4B, exogenous iron levels regulated, via Fur, the expression of FhuD2. Indeed, while FhuD2 expression was not detected in cells grown in the presence of either 50 μM FeCl3 (Fig. 4B, lane 3) or 10 μM FeCl3 (Fig. 4B, lane 4), it was detected in cells grown in the presence of 1 μM EDDHA (Fig. 4B, lane 5) and in H295 (RN6390 fur::Km) grown in the presence of 50 μM FeCl3 (Fig. 4B, lane 2).

FhuD1 and FhuD2 are involved in the transport of iron(III)-hydroxamates.

Given their similarity to FhuD homologs in E. coli and B. subtilis, we hypothesized that one or both of the FhuD1 and FhuD2 proteins were involved in iron(III)-hydroxamate uptake in S. aureus. To examine their role in the uptake of iron(III)-hydroxamates, both genes were insertionally inactivated and the resulting strains were tested for their ability to utilize a variety of iron(III)-hydroxamate complexes. Growth promotion by the various complexes was determined using the siderophore plate bioassay, and the data are summarized in Table 2. In comparison with the parent, RN6390, H430 (fhuD1::Km) showed no impairment in its ability to utilize any siderophores used by RN6390. In contrast, H364 (fhuD2::Tet) showed a reduced ability to utilize ferrichrome and ferrioxamine B and a complete inability to utilize aerobactin and coprogen for growth under iron-restricted conditions. Transport of all hydroxamate siderophores was completely abolished in strain H431 (fhuD1::Km fhuD2::Tet). Thus, the product of the fhuD2 gene appears to be the only one of the two that functions to mediate transport of aerobactin and coprogen. This is further illustrated by the observation that the fhuD2 gene in multicopy can fully restore transport of all iron-hydroxamates to the fhuD1::Km fhuD2::Tet double mutant but that the fhuD1 gene in multicopy (from pMTS40) is capable of restoring transport only of ferrichrome and ferrioxamine B. Moreover, this restored ability to utilize ferrichrome and ferrioxamine B was comparable to that seen in wild-type RN6390. The transport-defective phenotypes of the various fhuD mutations were specific for the hydroxamate-type siderophores, since their inactivation had no affect on the ability of S. aureus to utilize the catecholate siderophore enterobactin or the siderophores(s) extracted from culture supernatants of iron-limited RN6390.

TABLE 2.

Utilization of siderophores by RN6390 and derivatives

| Siderophore | Growth promotiona

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RN6390 | H430 (fhuD1::Km) | H430 + pMTS40 | H364 (fhuD2::Tet) | H364 + pMTS37 | H431 (fhuD1::Km fhuD2::Tet) | H431 + pMTS40 | H431 + pMTS37 | |

| Ferrichrome | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | − | ++++ | ++++ |

| Aerobactin | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | − | ++++ | − | − | ++++ |

| Ferrioxamine B (Desferal) | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | − | ++++ | ++++ |

| Coprogen | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | − | ++++ | − | − | ++++ |

| Alcaligin | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Rhodotorulic acid | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Enterobactin | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| RN6390 siderophore(s) | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

Growth response to siderophores on TMS plates was classified as follows: ++++, very good growth; ++, growth; −, no growth.

Western immunoblotting, using FhuD2-specific antisera, confirmed the presence of FhuD2 in detergent extracts of iron-limited RN6390 and H430 (fhuD1::Km) (Fig. 4C, lanes 2 and 3, respectively) and confirmed its absence in H364 (fhuD2::Tet) (Fig. 4C, lane 4) and H431 (fhuD1::Km fhuD2::Tet) (Fig. 4C, lane 6). As is evident from these results, the FhuD2-specific antisera do not cross-react with FhuD1, since no reactive protein is seen in strain H364 (fhuD2::Tet). High-level expression of FhuD2 is detected in strains containing the fhuD2 gene cloned on a multicopy plasmid. (Fig. 4C, lanes 5 and 7). In these two strains, an additional antiserum-reactive band appeared that migrated slightly faster in SDS-polyacrylamide gels than the mature FhuD2 lipoprotein. The nature of this protein is unconfirmed, but it may represent a form of FhuD2 that is not fully processed or a breakdown product of FhuD2 resulting from its high-level expression.

DISCUSSION

S. aureus is capable of utilizing both endogenous and heterologous siderophores to promote its growth in iron-restricted environments. Iron(III)-siderophore complexes require an ATP-dependent mechanism to be transported across the membrane, and this is facilitated by the action of traffic ATPases. Indeed, we have recently identified the membrane-localized traffic ATPase that facilitates the import of iron(III)-hydroxamate complexes (26). In this report, we describe the identification and characterization of two additional genes, fhuD1 and fhuD2, that encode proteins involved in the transport of iron(III)-hydroxamate complexes. fhuD1 and fhuD2 belong to extracellular solute-binding protein family 8 (28) and represent the first lipid-modified proteins in S. aureus with a characterized role in iron(III)-siderophore transport. Although the two proteins share significant amino acid similarity with the B. subtilis FhuD protein, they also share low but significant similarities with the periplasmic FhuD, FepB, and FecB proteins in E. coli. It is noteworthy that the levels of similarity seen between FhuD1 or FhuD2 and FhuD in B. subtilis or E. coli are significantly lower than similarities between components of the respective ATPases and permeases in these bacteria. Indeed, between S. aureus and E. coli, total similarities between the respective components of the traffic ATPase are greater than 50% in all cases, and this value is even higher for functionally equivalent proteins in S. aureus and B. subtilis. That substrate binding proteins are less conserved between different bacterial genera than the cognate membrane-associated proteins appears to be a general rule and is not unique to iron transport systems (10, 15).

The crystal structure of E. coli FhuD has recently been reported (8). The structure indicates that periplasmic FhuD is a kidney bean-shaped bilobate protein that does not adopt the classical periplasmic ligand binding protein fold observed in most structurally characterized periplasmic ligand binding proteins, instead possessing a shallow groove that acts as the iron(III)-hydroxamate receptor, resulting from a single α-helix that links the N-terminal and C-terminal globular domains of the protein. The structure was determined for FhuD in its liganded form, thus allowing identification of contact sites between FhuD and the hydroxamic acid moieties of the iron-siderophore complex. A visual examination of the deduced amino acid sequences of FhuD1 and FhuD2 does not reveal any striking similarities to E. coli FhuD in these regions of the proteins. Given their altered substrate specificities, their direct exposure to the extracellular milieu, and their existence as acylated proteins, as opposed to the functionally related soluble and periplasmic FhuD in E. coli, structure-function studies of FhuD1 and FhuD2 should provide novel insights into the mechanism of iron-siderophore transport in bacteria. These studies are currently under way in our laboratory and are timely, in light of the fact that the biochemical analysis of membrane-associated substrate binding proteins in gram-positive bacteria has lagged far behind that of the periplasmic binding proteins in gram-negative bacteria.

While the genome of S. aureus contains a single copy of the genes encoding components of the iron(III)-hydroxamate traffic ATPase [fhuCBG; insertional inactivation of fhuG abolished transport of all iron(III)-hydroxamate complexes (26)], as described in this report, two S. aureus lipoproteins are involved in uptake of various iron(III)-hydroxamates in this bacterium. This is reminiscent of a somewhat similar system presumably operating in B. subtilis; previous observations, and data arising from the sequenced B. subtilis genome, predict that more than one iron(III)-hydroxamate binding protein may be present in this bacterium. Indeed, among three types of mutants selected in B. subtilis, Schneider and Hantke (25) described the isolation of foxD (deficient in ferrioxamine uptake) mutants in addition to fhuD (deficient in ferrichrome and coprogen uptake) mutants, the latter being the focus of that particular study. Although the foxD mutant phenotype has not been characterized further, these data suggest that potentially a second binding protein, responsible for ferrioxamine uptake, is present in B. subtilis. B. subtilis genomic sequences reveal that, in addition to fhuD, at least one other potential gene, yclQ, may encode a iron(III)-hydroxamate binding protein (18). This ORF might well be allelic with foxD, which was described earlier (25). BLAST searches of the databases showed that the deduced amino acid sequences of two additional B. subtilis ORFs, yvrC and yxeB, show similarity to S. aureus FhuD2 and FhuD2; however, their functions remain uncharacterized.

Although there are two FhuD homologs in S. aureus, they possess overlapping, but not identical, substrate specificities. It is unclear whether S. aureus actually benefits from the presence of both fhuD1 and fhuD2. The presence of FhuD1, apparently not required in S. aureus containing a functional FhuD2 protein, may provide S. aureus with a selective advantage in the event of mutation. However, the affinity for various iron-hydroxamate chelates may be different between FhuD1 and FhuD2, potentially making one the preferred or dominant cell surface “receptor” for iron(III)-hydroxamates in all or selective environments. At this point, we have no data to indicate that expression of FhuD1 and FhuD2 is differentially regulated by any factor other than iron.

It is clear from available genomic sequences that fhuD1 and fhuD2 are not located in the vicinity of each other or fhuCBG on the S. aureus chromosome. This may be a reflection of significant genetic exchange and rearrangement throughout the evolution of the S. aureus species since genes whose products are involved in iron transport processes are generally clustered, although some exceptions do exist. We assume that both FhuD1 and FhuD2 interact with the traffic ATPase comprised of FhuC, FhuB, and FhuG, although we currently lack direct evidence for this interaction. There are other examples, however, of multiple solute binding proteins that bind different substrates but interact with the same membrane-associated transport complex. Indeed, one such system is the Ami system in Streptococcus pneumoniae, which utilizes three different solute binding proteins (AmiA, AliA, and AliB) encoded from three independent locations on the S. pneumoniae chromosome and one traffic ATPase (encoded by the amiCDEF locus) to transport oligopeptides (2). Presumably, as more membrane transport systems are identified and characterized, especially in the era of whole-genome sequencing, more membrane transport systems that exhibit functional redundancy in the solute binding component will be identified.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by operating grant MOP-38002 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to D.E.H. M.T.S. is the recipient of a doctoral award from CIHR, and D.E.H. is a CIHR New Investigator.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht-Gary A-M, Crumbliss A L. Coordination chemistry of siderophores: thermodynamics and kinetics of iron chelation and release. In: Sigel A, Sigel H, editors. Metal ions in biological systems. 35. Iron transport and storage in microorganisms, plants, and animals. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1998. pp. 239–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alloing G, de Philip P, Claverys J P. Three highly homologous membrane-bound lipoproteins participate in oligopeptide transport by the Ami system of the gram-positive Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Mol Biol. 1994;241:44–58. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ames G F, Mimura C S, Holbrook S R, Shyamala V. Traffic ATPases: a superfamily of transport proteins operating from Escherichia coli to humans. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1992;65:1–47. doi: 10.1002/9780470123119.ch1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bordier C. Phase separation of integral membrane proteins in Triton X-114 solution. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:1604–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun V, Hantke K, Köster W. Bacterial iron transport: mechanisms, genetics, and regulation. In: Sigel A, Sigel H, editors. Metal ions in biological systems. 35. Iron transport and storage in microorganisms, plants, and animals. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1998. pp. 67–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun V, Wu H C. Lipoproteins, structure, function, biosynthesis and model for protein export. In: Ghuysen J-M, Hakenbeck R, editors. Bacterial cell wall. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Science B.V.; 1994. pp. 319–341. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraborty T, Leimeister-Wächter M, Domann E, Harti M, Goebel W, Nichterlein T, Notermans S. Coordinate regulation of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes requires the product of the prfA gene. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:568–574. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.568-574.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke T E, Ku S Y, Dougan D R, Vogel H J, Tari L W. The structure of the ferric siderophore binding protein FhuD complexed with gallichrome. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:287–291. doi: 10.1038/74048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cockayne A, Hill P J, Powell N B L, Bishop K, Sims C, Williams P. Molecular cloning of a 32-kilodalton lipoprotein component of a novel iron-regulated Staphylococcus epidermidis ABC transporter. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3767–3774. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3767-3774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fath M J, Kolter R. ABC transporters: bacterial exporters. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:995–1017. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.995-1017.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffiths E. Iron in biological systems. In: Bullen J J, Griffiths E, editors. Iron and infection. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 1999. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths E, Williams P. The iron-uptake systems of pathogenic bacteria, fungi and protozoa. In: Bullen J J, Griffiths E, editors. Iron and infection. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; 1999. pp. 87–212. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guérout-Fleury A M, Shazand K, Frandsen N, Stragier P. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1995;167:335–336. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinrichs J H, Gatlin L E, Kunsch C, Choi G H, Hanson M S. Identification and characterization of SirA, an iron-regulated protein from Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1436–1443. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1436-1443.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins C F. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horsburgh M J, Ingham E, Foster S J. In Staphylococcus aureus, Fur is an interactive regulator with PerR, contributes to virulence, and is necessary for oxidative stress resistance through positive regulation of catalase and iron homeostasis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:468–475. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.468-475.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreiswirth B N, Lofdahl S, Bentley M J, O'Reilly M, Schlievert P M, Bergdoll M S, Novick R P. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305:680–685. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, Azevedo V, Bertero M G, Bessieres P, Bolotin A, Borchert S, Borriss R, Boursier L, Brans A, Braun M, Brignell S C, Bron S, Brouillet S, Bruschi C V, Caldwell B, Capuano V, Carter N M, Choi S K, Codani J J, Connerton I F, Danchin A, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuroda M, Ohta T, Uchiyama I, Baba T, Yuzawa H, Kobayashi I, Cui L, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Nagai Y, Lian J, Ito T, Kanamori M, Matsumura H, Maruyama A, Murakami H, Hosoyama A, Mizutani-Ui Y, Takahashi N K, Sawano T, Inoue R, Kaito C, Sekimizu K, Hirakawa H, Kuhara S, Goto S, Yabuzaki J, Kanehisa M, Yamashita A, Oshima K, Furuya K, Yoshino C, Shiba T, Hattori M, Ogasawara N, Hayashi H, Hiramatsu K. Whole genome sequencing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2001;357:1225–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee C Y. Cloning of genes affecting capsule expression in Staphylococcus aureus strain M. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1515–1522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrissey J A, Cockayne A, Hill P J, Williams P. Molecular cloning and analysis of a putative siderophore ABC transporter from Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6281–6288. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6281-6288.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng H L, Novick R P, Kreiswirth B, Kornblum J, Schlievert P. Cloning, characterization, and sequencing of an accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4365–4372. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4365-4372.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider R, Hantke K. Iron-hydroxamate uptake systems in Bacillus subtilis: identification of a lipoprotein as part of a binding protein-dependent transport system. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:111–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sebulsky M T, Hohnstein D, Hunter M D, Heinrichs D E. Identification and characterization of a membrane permease involved in iron-hydroxamate transport in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4394–4400. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.16.4394-4400.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiro T G, Saltman P. Polynuclear complexes of iron and their biological implications. Struct Bonding. 1969;6:116–156. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tam R, Saier M H., Jr Structural, functional, and evolutionary relationships among extracellular solute-binding receptors of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:320–346. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.320-346.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vagner V, Dervyn E, Ehrlich S D. A vector for systematic gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1998;144:3097–3104. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wada A, Watanabe H. Penicillin-binding protein 1 of Staphylococcus aureus is essential for growth. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2759–2765. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.10.2759-2765.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young I G, Gibson F. Isolation of enterochelin from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1979;56:394–398. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)56037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]