Abstract

Escherichia coli contains two major systems for transporting inorganic phosphate (Pi). The low-affinity Pi transporter (pitA) is expressed constitutively and is dependent on the proton motive force, while the high-affinity Pst system (pstSCAB) is induced at low external Pi concentrations by the pho regulon and is an ABC transporter. We isolated a third putative Pi transport gene, pitB, from E. coli K-12 and present evidence that pitB encodes a functional Pi transporter that may be repressed at low Pi levels by the pho regulon. While a pitB+ cosmid clone allowed growth on medium containing 500 μM Pi, E. coli with wild-type genomic pitB (pitA ΔpstC345 double mutant) was unable to grow under these conditions, making it indistinguishable from a pitA pitB ΔpstC345 triple mutant. The mutation ΔpstC345 constitutively activates the pho regulon, which is normally induced by phosphate starvation. Removal of pho regulation by deleting the phoB-phoR operon allowed the pitB+ pitA ΔpstC345 strain to utilize Pi, with Pi uptake rates significantly higher than background levels. In addition, the apparent Km of PitB decreased with increased levels of protein expression, suggesting that there is also regulation of the PitB protein. Strain K-10 contains a nonfunctional pitA gene and lacks Pit activity when the Pst system is mutated. The pitA mutation was identified as a single base change, causing an aspartic acid to replace glycine 220. This mutation greatly decreased the amount of PitA protein present in cell membranes, indicating that the aspartic acid substitution disrupts protein structure.

Escherichia coli contains at least two major systems for transporting inorganic phosphate (Pi). The low-affinity inorganic phosphate transporter (Pit) is dependent on the proton motive force for energy and is constitutively expressed (30, 31, 49). When Pi is plentiful, this is the major uptake system for phosphate, with a reported apparent Km (Kmapp) of 25 μM (30) to 38 μM (50) in whole cells and 11.9 μM in membrane vesicles (43). If the external Pi concentration is below the millimolar range, the high-affinity phosphate-specific transport (Pst) system is induced. This has a Kmapp of around 0.2 μM (30, 50). The Pst system is a complex of four proteins, including a periplasmic binding protein, which is energized by ATP and belongs to the ABC transporter family (7, 15, 47). The pst operon contains five genes under pho regulon control (1, 40, 41), which induces a range of genes when the phosphate supply is limited. Both the Pit and Pst systems are highly specific for Pi (30). Another two transporters accept Pi as a low-affinity analogue for either glycerol-3-phosphate (glpT) (18) or glucose-6-phosphate (uhpT) (29, 53), but in the absence of Pit and Pst activity, these latter two systems cannot support cell growth when supplied with Pi (38).

Divalent cations, such as Mg2+ or Ca2+, were shown elsewhere to be essential for Pit activity (32), and experiments by van Veen et al. (43, 44) indicate that Pit forms a soluble neutral metal phosphate (MeHPO4) complex which is symported with a proton. This is supported by the recent identification of a pitA mutant that accumulates reduced amounts of zinc(II), conferring resistance to toxic external concentrations of zinc (4). Efflux and homologous exchange of metal phosphate can occur under particular conditions, but there is no mixed exchange of metal phosphate for Pi, glycerol-3-phosphate, or glucose-6-phosphate (43). Interestingly, Beard et al. (4) suggest that PitA may also play a role in Zn2+ efflux when the ion reaches highly toxic external concentrations.

The Pit transport system was first reported by Willsky et al. (49) when mutations in the Pst system of several E. coli K-12 strains revealed a second Pi transporter. When a pst mutation was introduced into strain K-10, there was no measurable Pi transport, indicating that Pit is nonfunctional. This lesion was isolated as an α-glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) auxotroph and mapped at min 78.51 on the E. coli genome (37, 38) and is called pitA (Swiss Protein P37308). Since these studies were done, the sequencing of the E. coli genome has revealed the presence of another putative phosphate transporter gene, designated pitB, at min 67.44 (5) (Swiss Protein P43676). This gene has 75% sequence identity to pitA. If pitB is also a functional phosphate transporter, it may have contributed to the kinetic values and substrate specificities determined in earlier studies. These studies used strains in which the Pst system was repressed and/or mutated (30, 44, 50). Alternatively, the pitB gene may not encode a Pi transporter, as cysP is a sulfate permease from Bacillus subtilis which has some sequence identity with the Pit family of transporters but not with sulfate transporters (24).

Elvin et al. (10) located and cloned the pitA gene, overexpressed it, and partially purified the protein. This paper describes the cloning of pitB and the demonstration that pitB is a Pi transporter which appears to be repressed or inactivated by the pho regulon. In addition, the E. coli K-10 pitA mutation is identified, and the kinetic parameters of the PitA and PitB proteins are investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Description of E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics and/or background strain | Construction or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pAN686 | pitA+ | ClaI/SphI fragment from pCE27 (10) in pBR322 |

| pAN920 | pitA+ (opposite orientation from pAN686) | SalI/BamHI fragment from pAN686 in pBR322 |

| pAN656 | pitB+; long upstream region (1,403 nucleotides) | ClaI/BamHI fragment from AN2538 in pBR322 |

| pAN1116 | pitB+; short upstream region (206 nucleotides) | SspI/ClaI fragment from pAN656 in EcoRV/ClaI sites of pBR322 |

| pAN1243 | pitA1 | PCR product from AN3066 in pBR322 |

| pAN1244 | pitA G220D mutation | Site-directed mutagenesis of pitA+ in pBR322 |

| Strains | ||

| AN248 | pit+pst+ K-12 strain | 30 |

| AN3066 | pitA1 ΔpstC345 srl::Tn10 recA | 47 |

| AN3901 | pitB::Catr derivative of JC7623 | By recombination |

| AN3902 | pitA1 pitB::Catr ΔpstC345 | P1 AN3901 × AN3020 |

| AN3926 | pitB::Catr ΔpstC345 | P1 AN3901 × AN2537 |

| AN4080 | pitA1 pitB::Catr | P1 K-10 × AN3902 |

| AN4081 | pitA1 ΔpstC345 Δ(phoB-phoR) Kanr | P1 ANCH1 × AN3020 |

| AN4085 | pitA1 pitB::Catr ΔpstC345 Δ(phoB-phoR) Kanr | P1 ANCH1 × AN3902 |

| ANCH1 | Δ(phoB-phoR) Kanr | 54 |

| Strains with plasmids | ||

| AN3514; pBR322 control | pitA1 ΔpstC345 | pBR322/AN3066 |

| AN3135; pitB+ (long upstream) | pitA1 ΔpstC345 | pAN656/AN3066 |

| AN3171; pitA+ | pitA1 ΔpstC345 | pAN686/AN3066 |

| AN3531; pitA+ (opposite orientation) | pitA1 ΔpstC345 | pAN920/AN3066 |

| AN3937; pitA1 PCR from AN3066 | pitA1 ΔpstC345 | pAN1243/AN3066 |

| AN3938; pitA G220D | pitA1 ΔpstC345 | pAN1244/AN3066 |

| AN3903; pBR322 control | pitA1 pitB::Catr ΔpstC345 | pBR322/AN3902 |

| AN3904; pitA+ | pitA1 pitB::Catr ΔpstC345 | pAN920/AN3902 |

| AN3905; pitB+ (short upstream) | pitA1 pitB::Catr ΔpstC345 | pAN1116/AN3902 |

Cosmid cloning and sequencing of pitB.

Chromosomal DNA was prepared from a recA derivative of K-12 strain AN2537 (ΔpstC345) (39) and partially digested with HindIII to generate fragments of approximately 20 kb. These fragments were ligated into the cosmid cloning vector pHC79 and packaged into λ heads with extracts prepared from the lysogen-induced strains BHB2690 (prehead donor) and BHB2688 (packaging protein donor) (33). Packaged cosmids were adsorbed to AN3020 (pitA ΔpstC345) (47), a strain which shows no growth on minimal medium supplemented with 500 μM inorganic phosphate (Pi medium) (10). The mixture was spread onto Luria-Bertani plates containing 100 μg of ampicillin (AMP)/ml and 1 mM G3P. Either G3P or glucose-6-phosphate may be used as the phosphate source for pit pst strains, which cannot utilize Pi for growth (38). AMP-resistant colonies were replica plated onto Pi medium, and colonies were screened for growth in the absence of G3P, which indicated the presence of a functional Pi transport gene. Cosmid DNA was prepared from one of these isolates. Restriction analysis identified an approximately 3-kb ClaI/BamHI fragment that encoded a protein which complemented the pit mutation in AN3020, enabling growth of this strain on Pi medium. This DNA fragment was subcloned into the M13 vector mp18 and sequenced. The sequence is identical to the subsequently published pitB sequence (5). The pitA gene from plasmid pCE27 (10) was also sequenced and was found to be identical to the published sequence (37) (Swiss Protein P37308).

Preparation of cells for uptake.

Cells were grown and prepared as described in the work of Rosenberg et al. (30), with the addition of 5% Luria-Bertani medium to the overnight growing medium. AMP (50 μg/ml) was added where appropriate. All cells were washed three times, and suspensions were stored at 4°C for less than 30 min.

Measurement of phosphate uptake.

Measurement of 33Pi (NEN) uptake by cells was carried out under conditions in which Pi uptake was linear over time. These conditions were 1 to 15 μM Pi (PitA) or 10 to 100 μM Pi (PitB) over a 25-s period as previously described (30), except that the phosphate-free buffered “uptake” medium was pH 6.6 or 7.0 and the magnesium concentration was 1.8 or 10 mM. Data from kinetic experiments were analyzed by nonlinear regression using the Michaelis-Menten equation and the Graphpad Prism program.

Genetic techniques.

Plasmid DNA was prepared using the Magic Minipreps DNA purification system (Promega). Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the Amersham Sculptor in vitro mutagenesis system and PitA- or PitB-specific oligonucleotide primers. The nucleotide sequence at each mutation was checked by DNA sequencing. Transductions using phage PIkc were performed as previously described (28).

The pitA and pitB genes were amplified from genomic DNA, which was supplied by using approximately 0.2 μl of a single AN3066 colony mixed in 100 μl of water. The pit gene sequences were amplified by PCR using nucleotide primers complementary to the 5′ and 3′ regions flanking the open reading frames (ORFs), beginning with approximately 40 upstream nucleotides and ending just after the translation termination codons. BamHI sites were included at the distal ends of each primer (Table 2). The thermostable Pfu DNA polymerase was used in order to minimize introduction of errors by PCR (23). A longer pitB+ PCR product including 319 nucleotides upstream of the ORF was also prepared. The PCR products were purified using the Wizard PCR Purification system (Promega) and cloned into M13mp18, and several isolates of each were sequenced.

TABLE 2.

Primers for amplification of E. coli pit genes

| Sequence | Primer |

|---|---|

| pitAa | 5′ CTGAGGATCCGCCGCGTTCATGTCCT |

| 3′ TGACGGATCCGTTTTGGTGCGTACGATTACAG | |

| pitBa | 5′ GTCAGGATCCATGCGTCCGTTCGTAAATTC |

| 3′ CGCCGGATCCGGGCATTTTCAGGAAG | |

| pitBb | 5′ AGAGGGATCCTGAACCGTTAATTG |

| 3′ CACTGGATCCGGTGTTGGTTGATG |

Includes about 40 upstream nucleotides.

Includes 319 upstream nucleotides.

Inactivation of genomic pitB.

The chloramphenicol resistance gene from pBR328 was excised with the restriction endonucleases AatII and SauI, 5′ overhangs were filled in, and 3′ overhangs were digested by T4 DNA polymerase 1; then the gene was ligated into the StuI site in pitB in pAN656 to create pAN1193. Genomic replacement of wild-type pitB was carried out by transforming pAN1193 into the recB21 recC22 sbcB15 sbcC201 mutant strain JC7623 as previously described (26). The insertion of pitB::Cat was checked by PCR. P1 transduction was then used to transfer pitB::Cat into pstC (AN2537) and pitA pstC (AN3020) strains. Recipients were selected by resistance to 50 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. Successful removal of wild-type pitB was confirmed by PCR. The rapid spray alkaline phosphatase assay (6) showed that alkaline phosphatase was derepressed under high-phosphate conditions (Luria-Bertani medium plus 1 mM G3P), indicating the presence of ΔpstC345.

Inactivation of the pho regulon.

The phoB-phoR operon deletion from ANCH1 (54) was transduced into AN3020 and AN3902 and selected for by resistance to kanamycin. Inactivation of the pho regulon was confirmed by a negative result with the rapid spray alkaline phosphatase assay from cells grown on Luria-Bertani medium.

Isolation of membrane fraction.

Two-liter cultures of E. coli strains were grown to stationary phase in Luria-Bertani medium plus 34 mM glucose, 100 μg of AMP/ml, and 1 mM G3P, as required. The membrane fraction was prepared by passing the cells through a Sorvall Ribi cell fractionator, followed by centrifugation and ammonium sulfate precipitation, as previously described (9). The protein concentration of each sample was determined.

Polyclonal antipeptide antibody.

The PitA peptide ARIHLTPAEREKKDC (from A188 to D201) and the equivalent sequence in PitB, DRIHRIPEDRKKKKC (from D188 to K201), are from an extramembranous loop in the putative folded structure. Rabbits were immunized with the PitA peptide coupled to a lysine core matrix via a C-terminal cysteine (22). The multiple antigen peptide system conjugate was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and emulsified with an equal volume of Freund's adjuvant (12), and 200 μg was injected subcutaneously. Standard sampling and injecting protocols were followed (16). Sera were isolated by centrifugation, and initial positive responses determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (11) were screened by Western blotting of the sera against the membrane fractions of AN3903 (pitA pitB), AN3904 (pitB), and AN3905 (pitA). This showed that there was no cross-reactivity between PitA antibody and the PitB protein. The PitB peptide was attached to Imject maleimide-activated keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The conjugate was partially dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide with sonication and then diluted with 1 volume of PBS. Injections and screenings were carried out as previously described for the PitA peptide.

Purification of antipeptide antibody.

Sera containing PitA antipeptide antibody were not purified. The PitB equivalent was isolated from sera by immunoaffinity purification (SulfoLink kit; Pierce) following a two-stage ammonium sulfate precipitation (16) and dialysis against PBS. The synthetic peptide column was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the dialyzed PitB antipeptide antibody solution was passed through the column three times.

Western blots.

The membrane fraction of various E. coli strains was solubilized at 150 μg (PitA Western blots) or 1 mg (PitB Western blots) of protein per ml. Electrophoresis was performed according to the method of Laemmli (20) using a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane by electroblotting. After blocking in 10% milk powder–10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–0.9% NaCl (blocking buffer), the polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was incubated with either polyclonal antipeptide PitA antibody diluted 1/500 in blocking buffer or polyclonal PitB antibody diluted 1/100. Alkaline phosphatase conjugated with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (DAKO) was applied at a 1/1,500 (PitA) or a 1/1,000 (PitB) dilution in blocking buffer. The blot was immunostained with Western Blue stabilized alkaline phosphatase substrate (Promega).

RESULTS

Cloning of pitA and pitB.

The pitA and pitB genes from E. coli strain K-12 were isolated and sequenced in this laboratory as described in Materials and Methods, and the ORFs and putative promoter regions were identical to the published sequences of pitA at nucleotides 3635272 to 3636771 (37) and pitB at nucleotides 3132887 to 3134386 (5) on the E. coli K-12 genome. The ORFs of pitA and pitB contain 1,497 nucleotides each, with 75% identity in the nucleotide sequences and 81% identity in the deduced amino acid sequences. Topological models suggest 10 putative transmembrane helices, with most sequence variation occurring in the putative hydrophilic loop regions.

Confirmation of pitA and pitB translation start codons.

To identify the start codons, attempts were made to overexpress pitA or pitB and purify the protein products. However these attempts were hindered by the toxicity of the overexpressed genes (unpublished data). Instead, the translation starts were identified by functional analysis of alleles carrying mutated start codons (34). Both pitA and pitB have an ATG codon at the beginning of a 1,497-nucleotide ORF, and the nucleotide sequence similarity between the two DNA fragments exists only over this ORF region, suggesting that these ATG codons may initiate translation of the Pit genes. These putative ATG start codons were changed to GTG and CTG, causing a progressive drop in the Pi uptake activity of these mutants (Table 3). Changing an ATG start codon to GTG or CTG would be expected to progressively reduce expression of these proteins. In addition, two termination codons inserted in frame only 13 nucleotides after the putative ATG start of pitB completely abolished all Pi uptake activity. pitA has a second in-frame ATG codon 232 nucleotides after the putative ATG start codon, but termination codons placed before (at 118 nucleotides) or after this methionine also abolished all uptake activity. The combination of the above results indicates that translation of the pit genes commences at the beginning of the identified ORFs.

TABLE 3.

Phosphate uptake activity of PitA and PitB with altered putative start codons

| Putative start codon | Comparison with wild-type Pi uptake activity (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| PitAa | PitBb | |

| Vector | <0.5 | <0.5 |

| ATG | 100 ± 1.6 | 100 ± 2.7 |

| GTG | 32.4 ± 0.6 | 8.4 ± 1.0 |

| CTG | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.5 |

Assayed at 6 μM Pi. Values are shown with standard errors of the means. n = 6; 100% = 45 nmol of Pi min−1 mg (dry weight)−1.

Assayed at 50 μM Pi. Values are shown with standard errors of the means. n = 3; 100% = 55 nmol of Pi min−1 mg (dry weight)−1.

Kinetic parameters of PitA and PitB.

To characterize the kinetic properties of PitA and PitB with respect to Pi uptake, AN3066 cells expressing either protein from the plasmid vector pBR322 were grown, deprived of phosphate, and assayed as described in Materials and Methods. The background strain AN3066 (pitA1 ΔpstC345) does not grow in minimal medium supplemented with 500 μM Pi (Pi medium) but will grow with the addition of G3P. Both pitA and pitB can support cell growth when expressed on plasmids in AN3066. The PitA protein has a Kmapp about 10-fold lower than that of PitB on pAN656 in whole cells (Table 4). While the Vmaxapp for PitA was relatively stable, PitB Vmaxapp values were variable, as indicated by the high error values. Magnesium concentration and pH were altered to allow comparison with kinetic parameters measured by other researchers. While the Kmapp values remained similar under these conditions, the Vmaxapp was lower for both PitA and PitB when the magnesium concentration was increased from 1.8 to 10 mM and the pH was increased from 6.6 to 7.0 (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Kinetic parameters for PitA and PitB

| Plasmida | Phenotype | Assay condition

|

Kmappb (n) | Vmaxappb (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | [Mg] (mM) | ||||

| pAN686 | pitA+ | 6.6 | 1.8 | 1.9 ± 0.1 (5) | 58 ± 4 (5) |

| 7.0 | 10.0 | 1.9 | 39 | ||

| pAN656 | pitB+ longc | 6.6 | 1.8 | 28.6 ± 1.4 (5) | 33 ± 9 (5) |

| 7.0 | 10.0 | 28.1 ± 1.0 (3) | 17 ± 3 (3) | ||

| pAN1116 | pitB+ shortd | 7.0 | 10.0 | 6.0 ± 0.5 (3) | 67 ± 2 (3) |

Host strain is AN3066 for all experiments.

Kmapp values are shown as micromolar concentrations with standard errors of the means. Vmaxapp values are shown as nanomoles of Pi minute−1 milligram (dry weight)−1 with standard errors of the means.

1,403 upstream nucleotides.

206 upstream nucleotides.

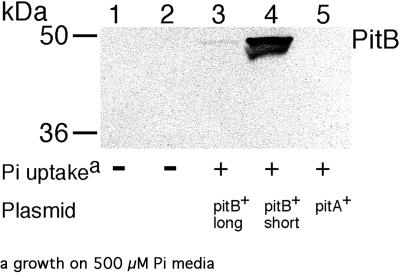

Interestingly, removing 1,196 nucleotides upstream of the pitB gene altered PitB's kinetic parameters. Decreasing the length of upstream DNA of pitB from 1,403 to 206 nucleotides in plasmid pAN1116 unexpectedly decreased the Kmapp fivefold, while the Vmaxapp increased fourfold and became less variable, as shown by the decrease in error values (Table 4). To determine if this increase in PitB activity correlated with the amount of PitB protein produced, Western blotting was carried out. Polyclonal antipeptide PitB antibody was used to measure the expression of PitB protein in the membrane fractions of strains which produce various levels of PitB activity. (The relevant plasmids are listed in Table 4.) There was no cross-reactivity with the PitA protein (Fig. 1, lane 5). Negligible PitB protein expression was found for the pitB+ pitA1 ΔpstC345 strain containing genomic pitB, which does not grow on Pi medium. The presence of plasmid pAN656 (pitB+ plus 1,403 upstream nucleotides) resulted in low levels of PitB protein in the cell membranes, while large amounts of PitB were produced when the upstream pitB DNA was decreased to 206 nucleotides in pAN1116. While this Western blot showed that the higher Pi uptake activity from pAN1116 correlated with increased PitB protein expression, the increase was much greater than the fourfold elevation in Vmaxapp noted in uptake experiments. This variation may be due to the different growth conditions used. Pi uptake assays were carried out on cells grown in minimal medium, while the cells used in Western blotting were cultured in Luria-Bertani medium (Materials and Methods). However, these experiments do indicate that the excision of 1,196 nucleotides upstream of pitB enhanced PitB protein expression from plasmid pAN1116, elevating PitB Pi uptake and increasing the transporter's affinity for Pi. The deleted region contains a large stem-loop sequence which may terminate transcription read-through from the plasmid (52). Whether increased transcription of the pitB gene was due to the removal of this stem-loop or due to interference with regulation at the pitB promoter was not investigated further.

FIG. 1.

Expression of PitB protein in different strains. Shown is a Western blot of purified polyclonal antipeptide PitB antibody against the membrane fraction of the indicated pitA1 ΔpstC345 strains (pitB genotype of the chromosome and plasmid). Lane 1, AN3903 (pitB, vector pBR322); lane 2, AN3514 (pitB+, vector pBR322); lane 3, AN3135 (pitB+, plasmid pitB+ with 1,403 upstream nucleotides); lane 4, AN3905 (pitB, plasmid pitB+ with 206 upstream nucleotides); lane 5, AN3904 (pitB, plasmid pitA+). Strains in lanes 2 and 3 have wild-type pitB on the genome, which produces no Pi uptake activity.

Identification of the E. coli K-10 Pit mutation in phosphate transport.

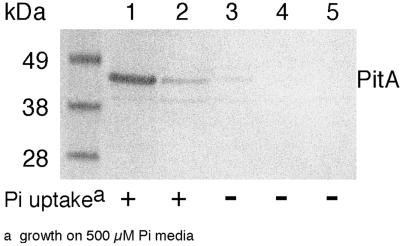

While E. coli K-10 has been characterized as deficient in Pit activity (49), the mutation has not been defined. Copies of pitA and pitB nucleotide sequences from the K-10 strain AN3066 were made by PCR. DNA sequencing revealed that the pitB ORF and the 319 upstream nucleotides are wild type. The pitA sequence contains a point mutation of G to A at nucleotide 658 in the ORF of the published sequence, which creates an amino acid change of G220D in the coding sequence (pitA1). To check that this single base change could account for the loss of Pit function in K-10, site-directed mutagenesis was used to recreate this mutation in a K-12 pitA+ gene. Both sequences were cloned into pBR322 and then transformed into AN3066, which is deficient in Pi transport (pitA pstC). Neither the mutant genomic pitA from AN3066 nor the site-directed pitA(G220D) allowed growth on Pi medium. This indicates that the single point mutation found in the AN3066 pitA is sufficient to create a nonfunctional Pit gene. Western blotting on the membrane fraction of whole cells, using polyclonal antipeptide PitA antibody, showed the level of expression of PitA protein inserted in the cell membrane (Fig. 2). While cells containing a wild-type pitA plasmid showed a strong band representing PitA protein (lane 1), cells containing the AN3066 genomic pitA (lane 4) or the site-directed pitA(G220D) (lane 5) had low levels of protein similar to the pitA mutant background strain (lane 3). Therefore, the G220D mutation seems to affect insertion of the protein into the membrane.

FIG. 2.

PitA protein expression from the AN3066 pitA1 mutation. Shown is a Western blot of polyclonal antipeptide PitA antibody against the membrane fraction of the indicated strains. All plasmids are in the AN3066 (pitA1) background unless otherwise stated. Lane 1, pAN920 (pitA+); lane 2, AN248 (genomic pitA+); lane 3, pBR322 (vector control); lane 4, pAN1243 (pitA1 PCR from AN3066); lane 5, pAN1244 (pitA G220D).

Functional characterization of PitA and PitB.

Plasmids containing either the pitA or pitB gene conferred Pi uptake activity on strain AN3066, which contains pitA1 ΔpstC345 and a wild-type pitB gene sequence. These assays show that a functional Pi transporter can be produced from the pitB gene when it is located on a plasmid but not when it is present only on the AN3066 genome. However, Pi uptake activity from the AN3171 strain, previously attributed to pitA, could in fact result from an interaction between the plasmid's PitA protein and the PitB protein expressed from the genome. To explore this further, a pitA+ pitB pstC mutant was created by inserting a chloramphenicol resistance gene into the pitB coding region of a pstC strain. This strain (AN3926) grew on Pi medium, indicating that the PitA protein can transport Pi in the absence of PitB. Wild-type pitA or pitB plasmids could also restore growth on Pi medium when transformed into a pitA pitB pstC triple mutant strain (AN3902). Hence, both PitA and PitB can transport Pi independently of each other.

Effect of the pho regulon on pitB activity.

The discovery that E. coli K-10, which lacks Pit activity (49), contains pitB which is wild type for the coding region and at least 319 upstream nucleotides poses an interesting problem. pitB was cloned due to the ability of the 3-kb fragment to complement for Pi uptake when in vector pHC79 (Materials and Methods), and Pi uptake assays confirmed that a functional Pi transporter was encoded on this fragment. Therefore, genomic pitB may be under regulation that is disrupted when the gene is placed on a plasmid.

In all experiments described so far, Pi uptake by PitA or PitB was isolated from Pi transport mediated by the Pst system by assaying strains which contain a Pst system deletion (ΔpstC345). This Pst deletion also constitutively induces the pho regulon (8), which is normally activated only under conditions of phosphate limitation. The pho regulon regulates a series of genes associated with phosphate transport and utilization. It is possible that PitB may be down-regulated by the pho regulon. Thus, a constitutive pho regulon could repress PitB activity at any phosphate concentration in the strains which we have used to assay Pit transport. To test this possibility, the phoB-phoR operon, which controls the pho regulon, was deleted from the pitB+ strain AN3020 (pitB+ pitA pstC), which did not grow on Pi medium, and the pitB pitA pstC triple mutant, which lacks pitB and was also unable to grow on Pi medium. Deletion of phoB-phoR enabled both strains to grow on Pi medium, indicating that both strains had one or more transport systems which were active in the absence of the pho regulon. However, the triple mutant, which contains no Pit or Pst transporters, had Pi uptake that was not significantly above background levels, while the pitB+ strain, AN4081, had a significant rate of Pi transport (Table 5). The fact that the control strain was able to grow on Pi medium but had no measurable Pi uptake may be attributed to the difference in Pi concentrations used in these experiments. Growth was assessed at 500 μM Pi, while Pi uptake was measured at 20 μM Pi. Thus, the growth of the control strain may be due to the presence of a transport system which has a lower affinity for Pi than that of either PitA or PitB. As the pho regulon controls a large number of genes involved in Pi assimilation (up to 137 proteins by two-dimensional gel analysis [42]), more than one system may be involved. The genomic PitB exhibited Pi transport of 4.4 nmol of Pi min−1 mg (dry weight)−1 at 20 μM Pi. By comparison, Pi uptake by PitB expressed from pAN656 was 5 to 25 nmol of Pi min−1 mg (dry weight)−1 at 20 μM Pi, and PitB on pAN1116, which produced greater protein expression and a lower Kmapp, had Pi uptake rates of 46 to 59 nmol of Pi min−1 mg (dry weight)−1 at 20 μM Pi (results not shown). Thus, these experiments show that chromosome-encoded pitB is active in the absence of the pho regulon.

TABLE 5.

Effect of the pho operon on PitB inorganic phosphate uptake activity

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Alkaline phosphatase activitya | Growth on minimal medium with source of phosphate:

|

Phosphate uptaked | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pi and G3Pb | Pic | ||||

| AN3066 | pitB+phoB+phoR+ | + | + | − | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| AN4081 | pitB+ | − | + | + | 4.4 ± 0.3 |

| AN4085 | − | + | + | 0.9 ± 0.2 | |

Rapid spray assay on cells grown on Luria-Bertani medium.

500 μM Pi and 1 mM G3P.

500 μM Pi.

Assayed at 20 μM Pi. Values are shown with standard errors of the means. n = 4. Values are nanomoles of Pi minute−1 milligram (dry weight)−1.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that E. coli contains two pit genes encoding proteins able to transport inorganic phosphate. pitA has previously been characterized, but we have shown that pitB also encodes a functional Pi transporter. Previously, Pit activity was reported to be constitutive (30, 49). While pitA appears constitutive, pitB may be regulated by the amount of available Pi. Our data suggest that pitB repression/inhibition is mediated through the pho regulon, since deletion of the phoB-phoR operon activated Pi uptake by pitB. The pho regulon is normally induced under conditions of Pi limitation, and Pi-dependent activation requires an interaction between the sensor protein PhoR and the Pst transport system. PhoR phosphorylates the transcriptional regulator PhoB, which then binds to a pho box consensus sequence within the promoter of genes in the pho regulon (46). However, the pho regulon of the ΔpstC345 strain used in our experiments is active at all Pi concentrations (8). The pitB+ strain AN3066 (pitA1 ΔpstC345) was unable to grow on Pi medium until the phoB-phoR operon was deleted. The rate of Pi uptake obtained from PitB expressed from the genome was higher than the control rates and was similar to the lower rates produced from plasmid pAN656. Pi uptake by pitB on plasmids pAN656 and pAN1116 may be caused by the increased copy number of pitB titrating out pho regulon inhibition. Thus, our experiments show that genomic pitB encodes a functional Pi transporter repressed/inactivated by the pho regulon, either directly through PhoB or via another pathway controlled by the pho regulon. The most likely explanation is that PhoB represses the pitB gene because this has already been observed for a pitB-like pit gene in Rhizobium meliloti using a pit::lacZ fusion. The R. meliloti pit gene was repressed under conditions of Pi limitation, but repression was relieved in a phoB mutant (2). As in E. coli, mutating the Pst transport system equivalent (phoCDET) caused derepression of the pho regulon, repressing pit at all Pi concentrations. Transforming a phoC R. meliloti strain with plasmid-borne pit increases cell growth on Pi medium to normal levels, suggesting that the repression can be overcome by supplying multiple copies of the gene. Only a two- to threefold increase in pit expression was needed to suppress the phoC phenotype (3).

While most studies on the pho regulon in E. coli have focused on the activation of genes, there is mounting evidence that the pho regulon may also repress some genes involved in phosphate assimilation. Two-dimensional protein experiments have shown that the pho regulon induces about 118 proteins and represses around 19 proteins (all with pIs of less than 7) under conditions of Pi limitation (42). More specifically, Willsky and Mallamy (51) have shown that two proteins which are repressed under Pi-limiting conditions are not repressed in phoB or phoR strains under the same conditions. Smith and Payne (36) propose that these are the periplasmic peptide binding proteins OppA and DppA.

Putative pho box sequences have been identified within the promoter regions of the R. meliloti orfA-pit operon and the E. coli opp and dpp operons (3, 36). However, while genes activated by the pho regulon have a pho box located 10 bases upstream from the −10 region (reference 27 and references therein), those operons which may be inhibited by the pho regulon have pho boxes either upstream of or overlapping the proposed −35 region. It has been suggested previously that this atypical positioning may reflect the negative regulation by PhoB (3, 36). While the pitB promoter region contains several putative pho box sequences in atypical positions, pitA also has similar sequences in the equivalent locations. Any potential pho box involved in negative regulation should be unique to pitB, as pitA is not repressed by the pho regulon. The binding sites for PhoB repression have not been characterized for any gene, so other DNA motifs may be involved. Thus, binding studies will be needed to locate any PhoB interactions with the pitB gene.

PitB's change in Kmapp indicates that a different mode of enzyme activity is also occurring in the protein expressed from the shortened plasmid pAN1116. An inhibitor which interacts with the PitB protein may be diluted out by the increased PitB expression, altering the Kmapp. Alternatively, higher concentrations of PitB may allow the protein to form a complex of monomers with a more effective mechanism. Although most secondary transporters are thought to function as monomers, this is not always the case. The sodium proton antiporter from E. coli has been crystallized as a dimer (48) and exists in the cytoplasmic membrane as a homo-oligomer (14). Glutamate transporters from the human brain have been shown previously to form dimers and trimers (17). There are now several examples of transporters that have dual affinity for their substrate and/or two mechanisms (13, 19, 21, 35, 55). Further investigation is needed to determine if this applies to PitB.

It is also possible that PitA undergoes similar changes in substrate affinity when protein expression is increased. Western blotting indicates that pitA expression is greatly elevated by placing it on a plasmid (Fig. 2), and our Kmapp of around 2 μM for pAN686 is significantly lower than the 11.9 to 38 μM range obtained by researchers using genomic Pit (30, 43, 50). However, the previously reported Kmapp values for Pit have been measured under conditions which make it impossible to attribute activity to pitA and/or pitB.

The K-10 pitA lesion was identified as a replacement of glycine 220 with aspartic acid, disrupting membrane insertion of the PitA protein. While it is not surprising that replacement of glycine, a small uncharged amino acid, with an aspartic acid could disrupt membrane insertion of the protein, it was unexpected that this relatively stable lesion was caused by a single point mutation. However, recreation of this mutation by site-directed mutagenesis produced identical behavior.

Our results indicate that PitA is likely to be active under a greater variety of conditions than is PitB. This situation of multiple Pi transporters with overlapping activities has been reported previously for Saccharomyces cerevisiae (25) and Neurospora crassa (45).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Edita Suziedeliene for the supply of E. coli strain ANCH1 and Hideo Shinagawa for the construction of strain ANCH1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amemura M, Makino K, Shinagawa H, Kobayashi A, Nakata A. Nucleotide sequence of the genes involved in phosphate transport and regulation of the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1985;184:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardin S D, Finan T M. Regulation of phosphate assimilation in Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) meliloti. Genetics. 1998;148:1689–1700. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.4.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardin S D, Voegele R T, Finan T M. Phosphate assimilation in Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) meliloti: identification of a pit-like gene. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4219–4226. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4219-4226.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beard S J, Hashim R, Wu G, Binet M R, Hughes M N, Poole R K. Evidence for the transport of zinc(II) ions via the pit phosphate transport system in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;184:231–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bracha M, Yagil E. A new type of alkaline phosphatase-negative mutants in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1973;122:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00337973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan F Y, Torriani A. PstB protein of the phosphate-specific transport system of Escherichia coli is an ATPase. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3974–3977. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3974-3977.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox G B, Webb D, Rosenberg H. Specific amino acid residues in both the PstB and PstC proteins are required for phosphate transport by the Escherichia coli Pst system. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1531–1534. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1531-1534.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox G B, Young I G, McCann L M, Gibson F. Biosynthesis of ubiquinone in Escherichia coli K-12: location of genes affecting the metabolism of 3-octaprenyl-4-hydroxybenzoic acid and 2-octaprenylphenol. J Bacteriol. 1969;99:450–458. doi: 10.1128/jb.99.2.450-458.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elvin C M, Dixon N E, Rosenberg H. Molecular cloning of the phosphate (inorganic) transport (pit) gene of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;204:477–484. doi: 10.1007/BF00331028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engvall E, Perlman P. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Quantitative assay of immunoglobulin G. Immunochemistry. 1971;8:871–874. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(71)90454-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freund J, McDermott K. Sensitization to horse serum by means of adjuvants. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1942;49:548–553. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu H H, Luan S. AtKuP1: a dual-affinity K+ transporter from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1998;10:63–73. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerchman Y, Rimon A, Venturi M, Padan E. Oligomerization of NhaA, the Na+/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli in the membrane and its functional and structural consequences. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3403–3412. doi: 10.1021/bi002669o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerdes R G, Rosenberg H. The relationship between the phosphate-binding protein and a regulator gene product from Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;351:77–86. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(74)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies. A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haugeto O, Ullensvang K, Levy L M, Chaudhry F A, Honore T, Nielsen M, Lehre K P, Danbolt N C. Brain glutamate transporter proteins form homomultimers. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27715–27722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi S-I, Koch J P, Lin E C C. Active transport of L-α–glycerophosphate in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:3098–3105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim E J, Kwak J M, Uozumi N, Schroeder J I. AtKUP1: an Arabidopsis gene encoding high-affinity potassium transport activity. Plant Cell. 1998;10:51–62. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu K H, Huang C Y, Tsay Y F. CHL1 is a dual-affinity nitrate transporter of Arabidopsis involved in multiple phases of nitrate uptake. Plant Cell. 1999;11:865–874. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.5.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu Y A, Clavijo P, Galantino M, Shen Z Y, Liu W, Tam J P. Chemically unambiguous peptide immunogen: preparation, orientation and antigenicity of purified peptide conjugated to the multiple antigen peptide system. Mol Immunol. 1991;28:623–630. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(91)90131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundberg K S, Shoemaker D D, Adams M W, Short J M, Sorge J A, Mathur E J. High-fidelity amplification using a thermostable DNA polymerase isolated from Pyrococcus furiosus. Gene. 1991;108:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90480-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansilla M C, de Mendoza D. The Bacillus subtilis cysP gene encodes a novel sulfate permease related to the inorganic phosphate transporter (Pit) family. Microbiology. 2000;146:815–821. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-4-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez P, Zvyagilskaya R, Allard P, Persson B L. Physiological regulation of the derepressible phosphate transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2253–2256. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2253-2256.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oden K L, DeVeaux L C, Vibat C R, Cronan J E, Jr, Gennis R B. Genomic replacement in Escherichia coli K-12 using covalently closed circular plasmid DNA. Gene. 1990;96:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90337-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okamura H, Hanaoka S, Nagadoi A, Makino K, Nishimura Y. Structural comparison of the PhoB and OmpR DNA-binding/transactivation domains and the arrangement of PhoB molecules on the phosphate box. J Mol Biol. 2000;295:1225–1236. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pittard J. Effect of integrated sex factor on transduction of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1965;89:680–686. doi: 10.1128/jb.89.3.680-686.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pogell B M, Maity B R, Frumkin S, Shapiro S. Induction of an active transport system for glucose 6-phosphate in Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1966;116:406–415. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(66)90047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg H, Gerdes R G, Chegwidden K. Two systems for the uptake of phosphate in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1977;131:505–511. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.2.505-511.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenberg H, Gerdes R G, Harold F M. Energy coupling to the transport of inorganic phosphate in Escherichia coli K-12. Biochem J. 1979;178:133–137. doi: 10.1042/bj1780133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell L M, Rosenberg H. The nature of the link between potassium transport and phosphate transport in Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1980;188:715–723. doi: 10.1042/bj1880715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarsero J P, Wookey P J, Pittard A J. Regulation of expression of the Escherichia coli K-12 mtr gene by TyrR protein and Trp repressor. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4133–4143. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4133-4143.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shelden M C, Dong B, de Bruxelles G L, Trevaskis B, Whelan J, Ryan P R, Howitt S M, Udvardi M K. Arabidopsis ammonium transporters, AtAMT1;1 and AtAMT1;2 have different biochemical properties and functional roles. Plant Soil. 2001;231:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith M W, Payne J W. Expression of periplasmic binding proteins for peptide transport is subject to negative regulation by phosphate limitation in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;79:183–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb14038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sofia H J, Burland V, Daniels D L, Plunkett III G, Blattner F R. Analysis of the Escherichia coli genome. V. DNA sequence of the region from 76.0 to 81.5 minutes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2576–2586. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.13.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sprague G F, Jr, Bell R M, Cronan J E., Jr A mutant of Escherichia coli auxotrophic for organic phosphates: evidence for two defects in inorganic phosphate transport. Mol Gen Genet. 1975;143:71–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00269422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Surin B P, Cox G B, Rosenberg H. Molecular studies on the phosphate-specific transport system of Escherichia coli. In: Silver S, Wright A, Yagil E, editors. Phosphate metabolism and cellular regulation in microorganisms. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Surin B P, Rosenberg H, Cox G B. Phosphate-specific transport system of Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequence and gene-polypeptide relationships. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:189–198. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.189-198.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torriani A, Ludtke D N. The molecular biology of bacterial growth. Boston, Mass: Bartlett Publishers; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 42.VanBogelen R A, Olson E R, Wanner B L, Neidhardt F C. Global analysis of proteins synthesized during phosphorus restriction in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4344–4366. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4344-4366.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Veen H W, Abee T, Kortstee G J, Konings W N, Zehnder A J. Translocation of metal phosphate via the phosphate inorganic transport system of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1766–1770. doi: 10.1021/bi00173a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Veen H W, Abee T, Kortstee G J, Pereira H, Konings W N, Zehnder A J. Generation of a proton motive force by the excretion of metal-phosphate in the polyphosphate-accumulating Acinetobacter johnsonii strain 210A. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29509–29514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Versaw W K, Metzenberg R L. Repressible cation-phosphate symporters in Neurospora crassa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3884–3887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wanner B L. Gene regulation by phosphate in enteric bacteria. J Cell Biochem. 1993;51:47–54. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240510110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Webb D C, Rosenberg H, Cox G B. Mutational analysis of the Escherichia coli phosphate-specific transport system, a member of the traffic ATPase (or ABC) family of membrane transporters. A role for proline residues in transmembrane helices. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24661–24668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams K A, Geldmacher-Kaufer U, Padan E, Schuldiner S, Kuhlbrandt W. Projection structure of NhaA, a secondary transporter from Escherichia coli, at 4.0 A resolution. EMBO J. 1999;18:3558–3563. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willsky G R, Bennett R L, Malamy M H. Inorganic phosphate transport in Escherichia coli: involvement of two genes which play a role in alkaline phosphatase regulation. J Bacteriol. 1973;113:529–539. doi: 10.1128/jb.113.2.529-539.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willsky G R, Malamy M H. Characterization of two genetically separable inorganic phosphate transport systems in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1980;144:356–365. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.1.356-365.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willsky G R, Malamy M H. Control of the synthesis of alkaline phosphatase and the phosphate-binding protein in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1976;127:595–609. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.1.595-609.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson K S, von Hippel P H. Transcription termination at intrinsic terminators: the role of the RNA hairpin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8793–8797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winkler H H. A hexose-phosphate transport system in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;117:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(66)90170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamada M, Makino K, Amemura M, Shinagawa H, Nakata A. Regulation of the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli: analysis of mutant phoB and phoR genes causing different phenotypes. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5601–5606. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5601-5606.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou J J, Trueman L J, Boorer K J, Theodoulou F L, Forde B G, Miller A J. A high affinity fungal nitrate carrier with two transport mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39894–39899. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]