Abstract

Background: Canadians are increasingly engaging in medial tourism. The purpose of this study was to review Canadians’ experiences with travelling abroad for cosmetic surgery, including primary motivations for seeking care outside of Canada. Methods: A qualitative analysis was conducted using semistructured interviews following a pre-determined topic guide. People who had undergone cosmetic surgery outside of Canada were interviewed. The interviews were transcribed and coded to determine motivational themes. Patients were recruited until thematic saturation was achieved. Results: Thematic saturation was achieved after recruitment of 11 patients. The most common motivational themes identified in this study for seeking cosmetic surgery outside of Canada included cost, post-operative care provided, marketing/customer service, and word-of-mouth. Member checking and theory triangulation were validation techniques used to verify identified themes. Mexico was the most common location for cosmetic tourism. The most common procedures were breast augmentation, mastopexy, and abdominoplasty. Participants gathered pre- and post-operative information primarily through pamphlets and contact with surgeons’ offices. Follow-up was only available for half of the participants in this study, and only 5 of the participants felt that they had received informed consent. Conclusions: The majority of participants engaged in cosmetic tourism due to cost reasons and the level of post-operative care provided.

Keywords: cosmetic surgery tourism, post-operative care, plastic surgery, motivational themes, cost

Résumé

Historique: Les Canadiens font de plus en plus de tourisme médical. La présente étude vise à analyser les expériences des Canadiens qui se rendent à l’étranger pour recevoir des soins de chirurgie esthétique, y compris leur motivation primaire à faire ce choix. Méthodologie: Les chercheurs ont effectué une analyse qualitative au moyen d’entrevues semi-structurées selon un guide de sujets préétablis auprès de personnes ayant subi des chirurgies esthétiques hors du Canada. Les entrevues ont été transcrites et codées pour en tirer les thèmes. Des patients ont été recrutés jusqu’à ce que tous les thèmes aient été abordés. Résultats: Onze patients ont été recrutés pour parvenir au point de saturation des thèmes. Les principales motivations pour obtenir une chirurgie esthétique hors du Canada incluaient les coûts, les soins postopératoires reçus, les services de marketing et à la clientèle et le bouche-à-oreille. Les chercheurs ont utilisé la vérification des membres et la triangulation des théories pour vérifier les thèmes établis. Le tourisme esthétique avait surtout lieu au Mexique. Les interventions les plus courantes étaient l’augmentation mammaire, la mastopexie et l’abdominoplastie. Les participants accumulaient l’information préopératoire et postopératoire d’abord à l’aide de dépliants et de contacts au bureau des chirurgiens. Seulement la moitié des participants à l’étude ont eu accès au suivi, et seulement cinq ont eu l’impression d’avoir donné leur consentement éclairé. Conclusions: La majorité des participants faisaient du tourisme esthétique pour une question d’argent et pour le taux de soins postopératoires fournis.

Background

Cosmetic tourism is the practice whereby people leave their country of residence to undergo cosmetic surgery procedures elsewhere. This phenomenon is prevalent globally and is receiving increasing attention as reports regarding the complications of cosmetic tourism are increasing. 1 -7 An estimated 52 000 Canadians travelled abroad for non-emergency care in 2014, when compared with around 41 000 the year prior. 8 Despite this increasing number, documentation of Canadian’s experiences is lacking, whereas this phenomena has been well-documented in other countries, 1,5 -7,9,10 including the United Kingdom 4 and United States. 11 Of concern is that if patients experience complications upon their return home, the original treating surgeon is unavailable to provide post-operative care. Additionally, in a publicly funded health care system, these complications become the burden of the taxpayer. The possibility of post-operative complications makes safety and informed consent a pertinent issue. Studies suggest that cosmetic tourism patients often receive preoperative information from unregulated resources. Word-of-mouth advice from family and friends is a prevalent source of information regarding surgery abroad, 12,13 in addition to online chat rooms and websites. 10,12 A review of the quality of information provided by online resources for cosmetic tourism demonstrated that the majority of websites did not include information on surgical complications and post-operative care. 13 The need for increased public awareness regarding the potential risks of cosmetic tourism has been identified. 6,14

With the concurrent increase of patients travelling abroad for surgery and the potential for people to experience post-operative complications upon return home, investigating the reason behind patients’ decision-making to participate in this global phenomenon is paramount. Cost savings are often assumed by practitioners to be the dominant motivating factor for patients to engage in cosmetic tourism. Companies operating within the cosmetic tourism landscape market often sell a vacation package that includes the cost of cosmetic surgery performed by US-trained surgeons. 9 Certain Canadian companies also use this vacation model to incentivize cosmetic tourism. 15 However, motivating factors other than cost and the desire for a vacation have been previously identified. Patients’ desire to conceal a procedure to their peers is one such additional factor, 11,16 as well as the long wait times in patients’ home countries. 2,16 Studies looking at motivations to engage in cosmetic tourism also found patients travelled to places where procedures were pioneered in pursuit of undergoing surgery by the most skilled experts. 14,17

Despite the availability of well-trained surgeons in Canada, Canadians are increasingly travelling elsewhere for surgical procedures. 8 The main purpose of this study was to better understand the main motivational themes directing people to engage in cosmetic surgery abroad. This information may help identify any deficiencies of care within the health care system and ways to improve care delivery. The secondary objective was to gain insight into patients’ experiences abroad, specifically as they pertained to sources of preoperative information, pre- and post-operative information received, and post-operative follow-up provided.

Methods

A qualitative analysis was conducted using semistructured interviews following a pre-determined topic guide based upon themes in existing literature. The inclusion criteria for patients in this study were Canadian residents who have had at least one cosmetic surgery procedure at an institution outside of Canada requiring referral to a Canadian plastic surgeon upon their return to Canada. Potential applicants were identified by 2 methods. Firstly, surgeons’ offices were contacted and asked if there was memory and/or record of a patient who received cosmetic surgery outside of Canada. Second, the plastic surgery resident team identified patients who were admitted to hospital with a history of cosmetic tourism. Patients deemed fit for the study were phoned by office staff to ask for consent to be contacted by the research team, or asked by the research team directly if admitted to hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and semistructured interviews were conducted. Interviews were recorded and transcribed for thematic coding after each interview. Once no new themes had been identified after 3 consecutive interviews, thematic saturation was deemed reached and data collection stopped. 18 Two separate reviewers evaluated the identified motivation themes. Interviews were conducted until theoretical redundancy was obtained and no further themes were identified. Identified themes were validated by 2 described methods: member checking and theory triangulation. 19 Member checking involved re-contacting each of the study participants and confirming or refuting the identified themes. We also validated the themes by comparing themes identified in this study with themes that had previously been identified in the literature. The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta.

Results

A total of 11 Canadian residents were interviewed. The most common cosmetic surgical procedures undergone abroad were breast augmentation (82%), mastopexy (64%), and abdominoplasty (55%) (Table 1). Eight of the 11 participants underwent more than one cosmetic procedure per general anaesthetic (Table 2). The estimated average cost incurred was CAD$11 495 (US$8550). Of the 11 study participants, only 2 individuals indicated that their flight cost was included in their overall expense, while 4 patients stated that their accommodations were included. The majority of patients (n = 9) received cosmetic surgery in Mexico, while the others had surgery in Costa Rica and Miami, United States.

Table 1.

Clinic Data Evaluating the Types of Cosmetic Procedures Received by Each Patient, as Well as the Percentage of Patients Who Received Each Procedure.a

| Cosmetic procedure | Number (#) of patients | Percentage (%) of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Breast augmentation | 9 | 82 |

| Mastopexy | 7 | 64 |

| Abdominoplasty | 6 | 55 |

| Brachioplasty | 3 | 27 |

| Thigh lift | 1 | 9 |

| Liposuction | 1 | 9 |

| Circumferential lower body lift | 1 | 9 |

| Brazilian butt lift | 1 | 9 |

a The publisher has permission to reproduce any previously published tables included in this article.

Table 2.

Description of Procedures Undergone by Each Participant per General Anaesthetic.a

| Participant no. | Procedure description | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominoplasty | Breast augmentation | Mastopexy | Liposuction | Thigh lift | Brachioplasty | Gluteal auto-augmentation | Lower body lift | |

| 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 7 | ✓ | |||||||

| 8 | ✓ | |||||||

| 9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

a The publisher has permission to reproduce any previously published tables included in this article.

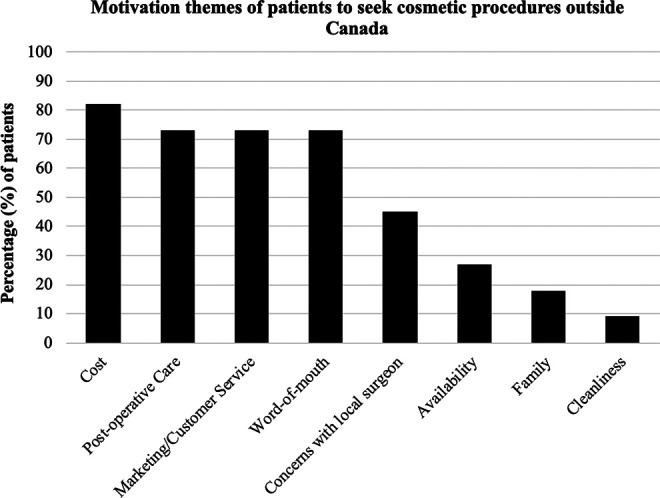

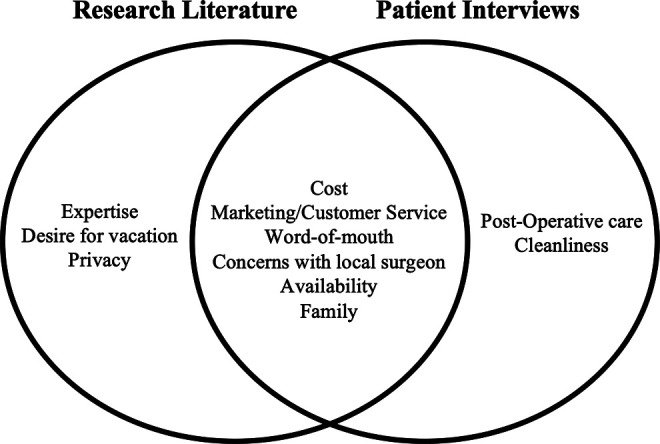

The most common motivational themes indicated by patients to seek cosmetic care abroad were cost (82%), post-operative care (73%), marketing/customer service (73%), and word-of-mouth (73%; Figure 1). Forty-five percent of patients expressed concern regarding the quality of care delivered by local surgeons. The common motivational themes identified in both patient interviews and previous studies were cost, marketing/customer service, word-of-mouth, concerns with local surgeon, availability, and family. Post-operative care and cleanliness were new themes identified in this study. In regard to post-operative care, patients specifically referred to the experience of having a nurse care for them after surgery abroad, including help with bathing, feeding, and dressing changes.

Figure 1.

Motivational themes of patients seeking cosmetic procedures outside Canada.

Among the possible channels for patients to access preoperative information, the most common were pamphlets from the office (55%) and communication with an office contact (55%). Two patients indicated that they directly visited the website to gather preoperative information, while social media, personal research, and communicating with a nurse were mentioned only one time each (Table 3). With regard to follow-up offered to patients, the majority of patients (n = 10) were told that a post-operative appointment would be available following the cosmetic procedure. However, only 5 patients were able to contact the office following care when seeking follow-up. Identified motivational themes were compared to themes previously identified in the literature (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Resources Used by Patients to Access Preoperative Information About Their Cosmetic Procedure.a

| Preoperative information | Number (#) of patients | Percentage (%) of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Pamphlet | 6 | 55 |

| Office contact (email, instant messaging, group chat) | 6 | 55 |

| Website | 2 | 18 |

| Social media platformsb | 1 | 9 |

| Personal research | 1 | 9 |

| Nurse | 1 | 9 |

a The publisher has permission to reproduce any previously published tables included in this article.

b Facebook.

Figure 2.

Comparing motivational themes found in the research literature and conducted patient interviews. Validation of motivational themes expressed by patients via theory triangulation and member checking.

Discussion

In accordance with a growing global trend, Canada has experienced its own rise in popularity and prevalence of medical tourism. 8 An important need arises to better understand the motivational themes of patients seeking care abroad due to the potential health complications associated with the surgical procedure, and the burden consequently endured by individuals and health care system. This need is outlined by Crooks et al 20 in their comprehensive review investigating the experience of medical tourists’, including motivations to seek care abroad. Of the 216 studies included in their study, only 5 did not draw conclusions from reviews and reports, for example, highlighting the need for studies gathering empiric data from this patient population. This study contributes to that paucity of data and represents the largest series of Canadians interviewed to investigate the motivational themes of people engaging in cosmetic tourism specifically.

The primary motivational theme identified by study participants to travel abroad for surgery was the cost of procedure(s), a finding that is consistent with the literature. 2,7,9,11,14,16,17,20,21 Not surprisingly, the overall cost of cosmetic procedures abroad, including people who paid separately for flights and accommodations, was less expensive than the same procedures offered in Canada; for example, one individual indicated that “…the surgery [breast augmentation] would cost $12,000 CAD [in Canada], but, if I went abroad, I could pay $5000 CAD.…” Several participants explained they would have preferred to undergo surgery in Canada, with one woman explaining they trialed “…3 different consultations with 3 different doctors in Edmonton [Canada], but I was getting quoted 20 to 25 thousand dollars for the procedures…” which was “…grossly expensive.…” This suggests that some individuals actively sought care locally prior to seeking care abroad.

Despite the high rate of complications experienced in cosmetic tourists, 2 -6,9,11 people were willing to forego the security of access to a local surgeon for decreased cost. One participant indicated that “…even with complications, the cost to return to Mexico for revision was less than the cost of having my primary surgery in Canada.” Unfortunately, some participants in this study, who were motivated by cost savings, ended up with large unanticipated costs to pay for management of their complications. One participant travelled abroad 4 times for repeated surgeries and explained that “…I was not able to save up the money to have surgeries in Canada, even though I would have rather it done here…and now…I have spent more than it would have been in Canada and I’m still botched.” Similarly, another patient stated that “…after all is said and done…I’m back to square one…and it’s going to cost me the same in the long run plus a lot more in regard to my mental wellbeing.”

Post-operative care was the second highest reason individuals engaged in cosmetic tourism in this study. This motivational theme had not been previously identified in the literature. There was a general desire by participants to be cared for after surgery by a nurse, for example, to aid in basic tasks of daily living such as cooking and bathing. Several of the participants in this study emphasized that they are sole parenting and living in small towns, making independent post-operative care unfeasible. Participants indicated that the features offered by surgeons’ offices abroad, such as transportation, continuous post-operative nursing care at hotel/resort, and food and laundry services, outweighed the negative components of having surgery away from home. As explained by a study participant, “…in Canada, you end up going home the day or two day after the procedure, while outside of Canada, they put me up in a ‘Recovery Boutique’ that was staffed by nurses 24/7. The care and facility were really nice and stress-free, which isn’t really an option in Canada, aside from hiring a home care nurse or another option that adds to the cost.” These data suggest that strategies utilized by American- and Canadian-based marketing businesses that impress upon the additional peri-operative services offered to patients who travel abroad for cosmetic surgery are effective. 9,15

Other principle motivational themes found in this study that are consistent with existing literature were marketing/customer service, 9,17 word-of-mouth, 12,22 availability 14,17 and concerns with local surgeons. 8 The underlying factor among these themes stemmed from the positive or negative perceptions developed by participants during their interactions with marketing agencies promoting cosmetic tourism, friends and family, or local surgeons during consultations. These findings emphasize the importance of face-to-face interactions and suggest that every aspect of the patient experience, beyond procedural outcomes, can influence the opinions and decisions of current and future patients. For example, one patient mentioned that “…I’m very aware of cleanliness and sterilization hygiene…and where he [surgeon] did his consult with me [in Canada], I was not impressed with the cleanliness of his waiting room and thought: “if this is only his waiting room, what’s the actual operating room going to be like.…” This suggests that that potential patients may equate tidiness to sterility and place significant weight on the visual outlook of consultation offices and waiting rooms rather than measurable sterility of the surgical suites. Surgeons can potentially leverage these findings to increase the overall patient experience by adapting a patient-centered approach to meet the specific needs of patients and enhancing facility amenities and service.

The major channels through which the participants in this study explored cosmetic tourism and gathered information regarding preoperative information included pamphlets and contact with non-medical office staff. This suggests that non-regulated sources of information are regularly utilized by individuals as sources of information. 13,17 With regard to the risks and potential complications understood by participants before engaging in cosmetic tourism, “…nobody really explained the risks to me…” and “…I received information the day of…” were examples of responses given. Many participants were not aware of the potential risks of surgery, for example “…obviously, there is infection risk associated with surgery, but I didn’t know the complications of fat grafting—no person explained it to me.” In terms of follow-up, the majority of participants in this study were assured they would have access to post-operative appointments in the event of complications. However, less than half of the people interviewed were able to contact their surgeon once they returned to Canada. One participant indicated, “…the minute I told my surgeon I had MRSA, they stopped responding to my calls and emails…,” while another patient explained that the “…office stonewalled me and wouldn’t listen to what I had to say, and [the surgeon’s] solution was full price revision.” These findings raise concerns about the quality of the consent process that cosmetic tourists are receiving, and the ethical implications of uninformed decision-making and the safety risks patients are exposed to in an unregulated model of care. 23

There are specific topics of concern in cosmetic surgery currently, including a growing risk of mycobacterium infections, 3 higher mortality rates associated with gluteal fat grafting due to pulmonary fat emboli, 24 and increased breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma in association with high-surface-area textured implants. 25,26 The use of unregulated sources of information and questionable consent processes encountered by participants in this study raises concerns about their awareness of these prevalent topics in cosmetic surgery. For example, multiple participants outlined concern regarding the use of textured implants by surgeons abroad. After consultation with a Canadian plastic surgeon, one participant was shocked to discover that the implants she received in Mexico were not approved by Health Canada. This raises concern that people engaging in cosmetic tourism may not always be informed on the regulations and practices unique to each country.

These findings suggest that guidelines developed by certified plastic surgeons and posted on online platforms, such as the Canadian Society of Plastic Surgeons website, might be a useful mechanism to ensure readily available access to thorough peri-operative information for people interested in cosmetic surgery. In addition, surgeons may benefit from using their private websites and social media outlets to educate prospective patients by providing credible information that outlines general risks of surgery, as well as additional risks of pursuing surgery abroad.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the information collected from participants was subject to recall bias. Due to recruitment methods, all of the participants in this study experienced post-operative complications, which may have influenced their responses for motivational factors to engage in cosmetic tourism. In addition, some of the participants had travelled and received their first procedure more than year prior being interviewed. This may have affected peoples’ ability to recall the reason(s) they had surgery abroad. Interestingly, 2 participants returned to the same country for repeat procedures, suggesting that their negative experiences with complications may not have influenced their motivation recounts. In addition, the study represents a relatively small sample size. More participants could have potentially been recruited if cosmetic tourism social media accounts were accessed, or advertisements were posted online. Accessing participants outside of the public health care system could also reach participants who partook in cosmetic tourism and did not suffer complications, reducing the risk of recall bias. Future studies in this area may benefit from larger participants numbers, as well as alternative methods to access participants, including the possibility of advertising. Lastly, this participant group represents Albertans only. People living in more populous areas with access to more diverse cosmetic surgery options (ie, Toronto, Ontario) may have different motivations to undergo surgery abroad.

Conclusion

This study represents the largest series of Canadian residents interviewed to obtain information on their motivation to engage in cosmetic tourism, as well as the principle methods through which they gathered pre- and post-operative information. The results of this study highlighted that cost, post-operative care, customer service, and word-of-mouth were primary motivational themes influencing people to travel abroad for cosmetic procedures. Interestingly, peoples’ for post-operative care is a new theme outlined in this study. Furthermore, Canadian residents are gathering pre- and post-operative information through a variety of unregulated sources, such as pamphlets and social media chat groups, potentially subjecting themselves to misinformation and self-reliance to understand potential health and financial risk associated with cosmetic tourism. The results of this study may help expand the awareness by physicians in regarding the motivational themes leading patients to engage in cosmetic tourism. Furthermore, this information can help create outlets for Canadian residents considering cosmetic tourism, cost-effective strategies for local surgeons to retain prospective patients, and guidelines for the health care system to navigate the increasing demands of patients returning home with complications.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Emilie M. Robertson contributed to article drafting, patient chart data collection, survey design and data collection, statistical analysis. Scott W. J. Moorman contributed to article drafting, data collection and data analysis. Lisa J. Korus contributed to study conception and design, manuscript revision. Presented at the Canadian Society of Plastic Surgeons Annual Meeting; 2018; Jasper, Alberta, Canada.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was approved by the Research Ethics Office at the University of Alberta.

ORCID iD: Emilie M. Robertson, MD https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3856-8198

References

- 1. Bell D, Holliday R, Jones M, Probyn E, Taylor JS. Bikinis and bandages: an itinerary for cosmetic surgery tourism. Tour Stud. 2011;11(2):139–155. doi:10.1177/1468797611416607 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Birch J, Caulfield R, Ramakrishnan V. The complications of cosmetic tourism—an avoidable burden on the NHS. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60(9):1075–1077. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2007.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cai SS, Chopra K, Lifchez SD. Management of Mycobacterium abscessus infection after medical tourism in cosmetic surgery and a review of literature. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;77(6):678–682. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000000745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jeevan R, Armstrong A. Cosmetic tourism and the burden on the NHS. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61(12):1423–1424. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2008.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Livingston R, Berlund P, Eccles-Smith J, Sawhney R. The real cost of cosmetic tourism cost analysis study of cosmetic tourism complications presenting to a public hospital. Eplasty. 2015;15:e34–e34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Melendez MM, Alizadeh K. Complications from international surgery tourism. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31(6):694–697. doi:10.1177/1090820X11415977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miyagi K, Auberson D, Patel AJ, Malata CM. The unwritten price of cosmetic tourism: an observational study and cost analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(1):22–28. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2011.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barua B, Ren F. Leaving Canada for Medical Care, Fraser Research Bulletin, 2015, Fraser Institute [online]. Accessed April 2018. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/leaving-canada-for-medical-care-2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chandawarkar RY. Ins and outs of outsourcing plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(6):1489–1491. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000239607.97411.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hanefeld J, Lunt N, Horsfall D, Smith R. Discussion on banning advertising of cosmetic surgery needs to consider medical tourists. BMJ. 2012;345(nov26 2). doi:10.1136/bmj.e7997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Franzblau LE, Chung KC. Impact of medical tourism on cosmetic surgery in the United States. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2013;1(7):e63. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000000003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hanefeld J, Lunt N, Smith R, Horsfall D. Why do medical tourists travel to where they do? the role of networks in determining medical travel. Soc Sci Med. 2015;124:356–363. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nassab R, Hamnett N, Nelson K, et al. Cosmetic tourism: public opinion and analysis of information and content available on the internet. Aesthet Surg J. 2010;30(3):465–469. doi:10.1177/1090820X10374104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iorio ML, Verma K, Ashktorab S, Davison SP. Medical tourism in plastic surgery: ethical guidelines and practice standards for perioperative care. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2014;38(3):602–607. doi:10.1007/s00266-014-0322-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turner L. Beyond medical tourism: Canadian companies marketing medical travel. Glob Health. 2012;8(1):16. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-8-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lunt N, Carrera P. Medical tourism: assessing the evidence on treatment abroad. Maturitas. 2010;66(1):27–32. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Glinos IA, Baeten R, Helble M, Maarse H. A typology of cross-border patient mobility. Health Place. 2010;16(6):1145–1155. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Patton M, Cochran M. A Guide to Using Qualitative Research Methodology. Médecins Sans Frontières; 2002. Accessed April 2018. https://evaluation.msf.org/sites/evaluation/files/a_guide_to_using_qualitative_research_methodology [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid?. For the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284(3):357–362. doi:10.1001/jama.284.3.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crooks V, Kingsbury P, Snyder J, Johnston R. What is known about the patients’ experience of medical tourism? a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lunt N, Smith R, Exworthy M, Horsfall D, Mannion R. Medical Tourism: Treatments, Markets and Health System Implications: A Scoping Review. OECD; 2011:55. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yeoh E, Othman K, Ahmad H. Understanding medical tourists: word-of-mouth and viral marketing as potent marketing tools. Tour Manag. 2013;34:196–201. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2012.04.010 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crooks VA, Turner L, Cohen IG, et al. Ethical and legal implications of the risks of medical tourism for patients: a qualitative study of Canadian health and safety representatives’ perspectives. BMJ Open. 2013;3(2). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-00230225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mofid MM, Teitelbaum S, Suissa D, et al. Report on mortality from gluteal fat grafting: recommendations from the ASERF task force. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(7):796–806. doi:10.1093/asj/sjx004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loch-Wilkinson A, Beath KJ, Knight RJW, et al. Breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma in Australia and New Zealand: high-surface-area textured implants are associated with increased risk. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(4):645–654. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000003654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coroneos CJ, Selber JC, Offodile AC, Butler CE, Clemens MW. US FDA breast implant postapproval studies: long-term outcomes in 99,993 patients. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):30–36. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]