Dear Editor,

We read with interest the paper from Abadías‐Granado et al. 1 reporting on two patients aged 64 and 60 years who experienced generalized pustular figurate erythema (GPFE) after the instart (2 and 3 weeks, respectively) of the same protocol for SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia, consisting of hydroxychloroquine (400 mg/day) plus lopinavir/ritonavir, teicoplanin ± azithromycin; the report also raises attention on a possible coexistence of COVID‐19 skin manifestation.

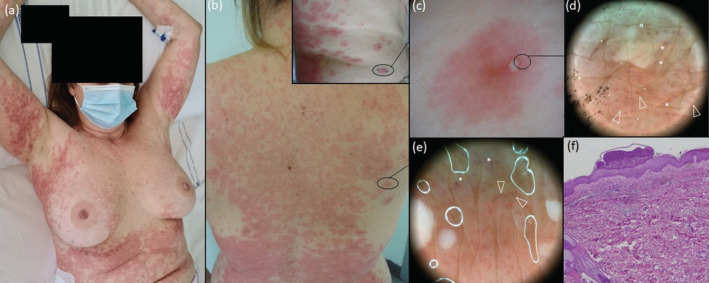

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, we hospitalized two women, aged 57 (Figure 1a,b) and 50 years (Figure 2a–c), due to the occurrence of generalized rash: In both cases, hydroxychloroquine had been introduced for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (400 mg/day) 22 and 30 days before. Fever was absent. Clinical observation revealed widespread non‐follicular pustules surrounded by an erythematous halo that evolve into targetoid lesions and rapidly coalesce to form plaques with annular or arcuate patterns. Focally, pustular erythema was present on the top of active/raised lesions' borders. Trunk, face, proximal extremities and skin folds were involved, with sparse lesions on the distal extremities. Genital mucosae were spared, and Nikolsky's sign was negative. ENT examination detected no oral mucosae involvement. Intense itching was referred by both patients.

FIGURE 1.

Clinical appearance at presentation time, 26 days after starting hydroxychloroquine therapy, exhibiting lesions in different stages: numerous tiny pustules pustular surrounded by an erythematous halo (e, polarized dermoscopy 17×) evolved into targetoid lesions with raised outer ring that coalesced into wide plaques on the whole trunk (a,b) and remained sparse on the extremities (b). Polarized dermoscopy 30× highlights the presence of clods (asterisks) and curved vessels (arrowheads) along the pustules margin (d) and all over the erythematous halo around the pustule (f). Biopsy specimen from the right side revealed an intraepidermal pustule, lympho‐histiocytic infiltrates in the upper dermis, with dilated papillary capillaries and focal oedema, in absence of sign of vasculitis; focal exocytosis of neutrophils were also present near to the pustule [c, Haematoxylin–eosin, 50×].

FIGURE 2.

Clinical appearance of GPFE rash occurred 22 days after starting hydroxychloroquine therapy in a 50‐year‐old woman, involving the trunk and proximal extremities with the skin fold sparing. Numerous primary lesions (b, square) consisting of a millimetric pustule surrounded by an erythematous halo (c, polarized dermoscopy 17×) evolved into targetoid lesions with raised pustular borders and merged to form wide plaques (a,b). Polarized dermoscopy 30× reveals clods (asterisks) and curved vessels (arrowheads) along the pustules margin (d) and between pustules (e). Histopathological examination revealing subcorneal pustule with focal spongiosis and acanthosis with focal exocytosis of neutrophils; the upper dermis shows dilated capillaries, oedema, lympho‐histiocytic infiltrates with numerous neutrophilic granulocyte and occasional eosinophilic granulocytes [f, Haematoxylin–eosin, 50×].

Dermoscopic examination was performed polarized dermoscopy at different magnifications, 17× (DermLite photosystem®) and 30× (Medicam 1000, Fotofinder System®) over some newly developed lesions on the forearm and right side. On 17× dermoscopy, lesions appeared as non‐flaccid clear‐cut whitish pustules surrounded by an erythematous halo with undefined margins (Figures 1e and 2e). Dermoscopy 30x performed both on the pustule margin (Figures 1d and 2d) and on lesional skin near the pustule (Figure 1f) revealed numerous bright red curved vessels and clods 2 corresponding to dilated capillaries in dermal papillae. 9

When tested for SARS‐CoV‐2 before hospitalization both patients turned out to be positive, though without respiratory symptoms. Serologic investigations revealed moderately raised reactive C protein and no neutrophilic leucocytosis. Skin biopsies revealed subcorneal/intraepidermal pustular dermatosis with oedema and lympho‐histiocytic infiltrates in supper dermis (Figures 1c and 2f) consistent with a GPFE picture. 1 , 3 Patients underwent topical and systemic steroids treatment for 4 and 5 weeks.

Generalized pustular figurate erythema has been delineated as a distinct entity only recently 3 : indeed, within the 30 cases described to date, 1 , 3 the majority were described as typical or prolonged form of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) 4 , 5 or as generalized pustular ± annular psoriasis. 6 , 7 , 8 Skin manifestations occur within 20–25 days (while in AGEP within 24–48 h) and tend to respond slowly to corticosteroid therapy.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of GPFE dermoscopic features. The identification of those dermoscopic clues—that is tiny pustule surrounded an erythematous halo with evident curved vessels and clods—can be of help in recognizing GPFE cases presenting in late phase and/or modified by corticosteroid treatment 9 and in differentiating them from a variety of forms which can exhibit overlapping features, including erythema multiforme, AGEP, prolonged/recalcitrant AGEP, AGEP/SJS overlap and generalized annular pustular psoriasis. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Indeed, in erythema multiforme the clods are reddish‐purple in the central dusky zone and reddish in the outer red ring, with linear vessels at the periphery; in AGEP, no distinct vessels are visible around the millimetric pustules; in generalized annular pustular psoriasis the pustules are surrounded by regularly distributed dotted vessels. 10

In our opinion, based on the cases reported to date 1 and on those here presented, GPFE is to be considered as a drug‐reaction pattern strongly related to the hydroxychloroquine, whereas the role of COVID‐19 infection is more likely to be a concomitant association rather than a distinct trigger. On the other hand, COVID‐19 vaccine is likely to induce or exacerbate generalized pustular psoriasis. 6 , 7 , 8 However, further studies on COVID‐19‐positive and COVID‐19‐negative patients are warranted to define the list of GPFE causative agents.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to the publication of their case details.

This article is linked with Abadías‐Granado I. To view this article visit https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16903.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abadías‐Granado I, Palma‐Ruiz AM, Cerro PA, Morales‐Callaghan AM, Gómez‐Mateo MC, Gilaberte Y, et al. Generalized pustular figurate erythema first report in two COVID‐19 patients on hydroxychloroquine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(1):e5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kittler H, Riedl E, Rosendahl C, Cameron A. Dermatoscopy of unpigmented lesions of the skin: a new classification of vessel morphology based on pattern analysis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2008;14(4):3. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Generalized pustular figurate erythema: a newly delineated severe cutaneous drug reaction linked with hydroxychloroquine. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(3):e13380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mohaghegh F, Jelvan M, Rajabi P. A case of prolonged generalized exanthematous pustulosis caused by hydroxychloroquine – literature review. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6(12):2391–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mercogliano C, Khan M, Lin C, Mohanty E, Zimmerman R. AGEP overlap induced by hydroxychloroquine: a case report and literature review. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2018;8(6):360–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Romagnuolo M, Pontini P, Muratori S, Marzano AV, Moltrasio C. De novo annular pustular psoriasis following mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(8):e603–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elamin S, Hinds F, Tolland J. De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford‐AstraZeneca COVID‐19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:153–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Perna D, Jones J, Schadt CR. Acute generalized pustular psoriasis exacerbated by the COVID‐19 vaccine. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;17:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tognetti L, Cinotti E, Falcinelli F, Miracco C, Suppa M, Perrot JL, et al. Line‐field confocal optical coherence tomography (LC‐OCT) as a new tool for non‐invasive differential diagnosis of pustular skin disorders. JEADV. 2022. 10.1111/jdv.18324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Errichetti E, Stinco G. Dermatoscopy in life‐threatening and severe acute rashes. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38(1):113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.