Abstract

Background and aims

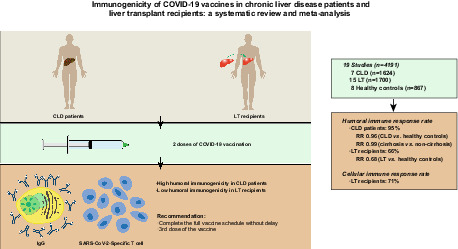

Chronic liver disease (CLD) patients and liver transplant (LT) recipients have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). The immunogenicity of COVID‐19 vaccines in CLD patients and LT recipients is poorly understood. The present study aimed to evaluate the immunogenicity of COVID‐19 vaccines in CLD patients and LT recipients.

Methods

We searched electronic databases for eligible studies. Two reviewers independently conducted the literature search, extracted the data and assessed the risk of bias of included studies. The rates of detectable immune response were pooled from single‐arm studies. For comparative studies, we compared the rates of detectable immune response between patients and healthy controls. The meta‐analysis was conducted using the Stata software with a random‐effects model.

Results

In total, 19 observational studies involving 4191 participants met the inclusion criteria. The pooled rates of detectable humoral immune response after two doses of COVID‐19 vaccination in CLD patients and LT recipients were 95% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 88%–99%) and 66% (95% CI = 57%–74%) respectively. After two doses of vaccination, the humoral immune response rate was similar in CLD patients and healthy controls (risk ratio [RR] = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.90–1.02; p = .14). In contrast, LT recipients had a lower humoral immune response rate after two doses of vaccination than healthy controls (RR = 0.68; 95% CI = 0.59–0.77; p < .01).

Conclusions

Our meta‐analysis demonstrated that COVID‐19 vaccination induced strong humoral immune responses in CLD patients but poor humoral immune responses in LT recipients.

Keywords: chronic liver disease, COVID‐19, immunogenicity, liver transplantation, vaccine

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- CLD

chronic liver disease

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- GRADE

grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation

- LT

liver transplant

- MMF

mycophenolate mofetil

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- NAFLD

non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

- OR

odds ratio

- RR

risk ratio

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Lay Summary.

The immunogenicity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) vaccines in chronic liver disease (CLD) patients and liver transplant (LT) recipients is poorly understood. We demonstrated that COVID‐19 vaccination elicited strong humoral responses in CLD patients but poor humoral immune responses in LT recipients. The findings indicate that CLD patients and LT recipients should complete the full vaccine schedule without delay and support the administration of a third dose of vaccine to LT recipients.

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus 19 disease (COVID‐19), caused by infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), has led to high levels of morbidity and mortality and is dramatically affecting healthcare systems all over the world. 1 Chronic liver disease (CLD) patients and liver transplantation (LT) recipients have well‐recognized deficiencies in humoral and cellular immunity, the so‐called immune dysfunction, which predisposes to infections. 2 , 3 CLD patients and LT recipients are reported to have an increased risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and worse outcomes compared to the general population. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8

COVID‐19 vaccines have been considered to be the most effective means of controlling the COVID‐19 pandemic. 9 Growing evidence indicates that COVID‐19 vaccines are safe and effective in the general population. 10 , 11 However, immunocompromised and immunosuppressed individuals may have reduced immune responses to COVID‐19 vaccines. To date, studies on immune responses of COVID‐19 vaccines in CLD patients and LT recipients have been lacking, because these populations were excluded from regulatory vaccine trials. The integration of findings across studies can offer a better understanding of the immunogenicity of COVID‐19 vaccines in these populations. Therefore, we conducted the first systematic review and meta‐analysis to assess the immunogenicity of COVID‐19 vaccines in CLD patients and LT recipients.

2. METHODS

This systematic review and meta‐analysis was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines 12 and was registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) 13 with the registration number CRD42021296904.

2.1. Search strategy

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Cochrane Library using predefined search terms for eligible studies published in English from December 2019 to April 2022. The main search terms included “COVID‐19”, “SARS‐CoV‐2”, “vaccine”, “liver transplantation”, “liver disease”, “cirrhosis”, “chronic liver diseases”, “non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease”, “immunogenicity”, “antibody”, “seroconversion”, “humoral immune response”, and “cellular immune response”. References from the included studies were also manually searched to identify additional studies. Two investigators (B.J.M. and A.K.W.) performed independently the search. Search strategy details for PubMed are provided in Table S1.

2.2. Outcomes of interest

The primary outcomes were the rates of detectable humoral immune response in CLD patients and LT recipients and the comparison of humoral immune responses between these populations and healthy controls. The secondary outcomes were the rates of detectable cellular immune response and risk factors for poor antibody responses.

2.3. Study selection

The eligibility of the studies was determined independently by two investigators (B.J.M. and A.K.W.). The inclusion criteria were: (i) participants: patients were CLD patients or LT recipients without previous COVID‐19 infection. If a study enrolled participants with and without previous infection, only participants without previous infection were included in this meta‐analysis; (ii) intervention: two doses of COVID‐19 vaccination; (iii) at least one of the outcomes of interest was reported; (iv) randomized controlled trial and cohort study were eligible. Any study that met one of the following conditions was excluded: (i) inadequate description of CLD patients or LT recipients from these studies on solid organ transplantation; (ii) if the number of patients in the study was below 10. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or consultation with the third investigator (F.K.).

2.4. Data extraction

Two independent investigators (F.K. and C.F.) extracted data and recorded them on the predefined form. The extracted information included the first author, year of publication, participant characteristics (gender, age, comorbidity and proportion of cirrhosis), sample size, details of the vaccination (type of vaccine and time interval between transplantation and first vaccination), assay used to assess antibody response, time interval between second vaccination and antibody measurement, immunosuppressive regimen and outcomes of interest. The authors of the studies were contacted for missing information, if necessary. Two investigators compared the data, and discrepancies were decided through discussion.

2.5. Quality assessment

Two independent investigators (Y.G. and X.L.Y.) assessed the risk of bias of included studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS). 14 According to the scale, the quality of each study was assessed by awarding participant selection a maximum of 4 points, outcome 3 points and comparability 2 points, yielding a maximum total of 9 points. The overall study quality was classified as good (7–9 points), moderate (4–6 points), or poor (0–3 points). The quality of the evidence was determined by the grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) approach. 15 Certainty levels (very low, low, moderate or high) were assigned to each result, based on risk of bias, publication bias, inconsistency, indirectness, intransitivity, imprecision and incoherence (difference between direct and indirect effects). Disagreements among investigators were settled by consensus.

2.6. Statistical methods

We conducted the meta‐analysis using Stata version 16.0. The meta‐analysis was conducted separately based on the patient type (CLD or LT). In the single‐armed meta‐analysis, the data from the studies were transformed using the double arcsine method to achieve normality of distribution before being pooled. The risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to compare the humoral immune responses between patients and healthy controls. The I 2 statistic was used as a measure of heterogeneity across studies. Heterogeneity was defined as high (>75%), moderate (25%–75%) and low (<25%). 16 Heterogeneity was determined using Cochran's Q‐statistics with a significance threshold of p < .1. 17 To mitigate the effects of between‐study heterogeneity on the findings of the analysis, we conducted the meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model. We performed the sensitivity analysis by removing one study at a time to observe the effects on the outcomes. Subgroup analyses were performed based on cirrhosis status, vaccine platform, vaccine type, assay of antibody testing and time interval between second vaccination and antibody measurement. Pooled odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI was used to calculate the pooled effect estimate of risk factor for poor antibody responses. Begg's and Egger's tests were performed to assess publication bias, and funnel plots were constructed to visualize asymmetry when the number of available studies for each analysis was ≥10.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study characteristics

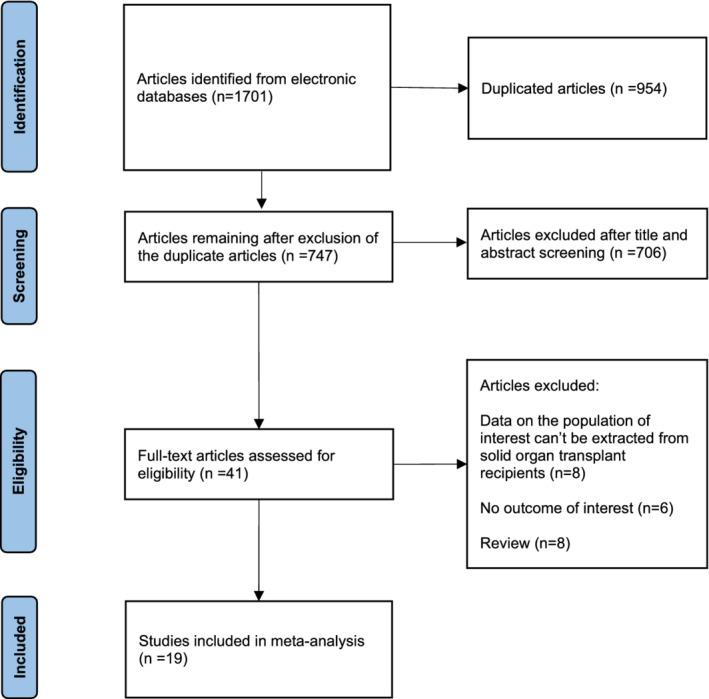

The initial search identified 1701 articles. After the removal of duplicates and other articles that were irrelevant to this study (based on title and abstract), 41 potentially relevant articles remained and their full texts were evaluated. Based on the inclusion criteria, 19 studies 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 that included 4191 participants (1624 CLD patients, 1700 LT recipients and 867 healthy controls) were included (Figure 1). Seven studies 18 , 24 , 26 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 included CLD patients and 15 studies 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 included LT recipients. Of the 19 studies, 15 studies 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 used mRNA vaccines (BioNTech vaccine: BNT162B2 or Moderna vaccine: mRNA‐1273) and 4 studies 18 , 24 , 35 , 36 used inactivated vaccines (Sinovac vaccine: CoronaVac, Sinopharm vaccine: BBIBP‐CorV and Sinopharm vaccine: WIBP‐CorV). Three studies 31 , 33 , 34 used mRNA vaccines and included a small proportion (0.8%–25%) of patients who received adenovirus vector vaccines (Johnson and Johnson vaccine: JNJ‐78436735 and AstraZeneca vaccine: AZD1222), but data were not reported separately, so these studies were included in the analyses of mRNA vaccines. All participants completed two doses of vaccination. The majority of the studies selected a time frame of 2–5 weeks after the second vaccination to assess the immune responses to COVID‐19 vaccines. Five studies 18 , 21 , 24 , 31 , 36 showed a low risk of bias (7‐8 points), with 14 studies 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 having a moderate bias risk (5‐6 points). Characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the assessment of the studies identified in the meta‐analysis.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Population | Sample size | Male (%) | Age, years, mean ± SD/median (IQR/range) | Comorbidity | Time after LT, years, mean ± SD/median (IQR/Range) | Type of vaccine | Type of antibody | Assay of antibody testing | Cut‐off for positive antibody response | Time interval between second vaccination and antibody measurement | Immunosuppressive regimen | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ai 2021 18 | CLD (cirrhosis 35.0%) | 437 | 63.6% | Median: 47.0 (IQR 38.0–56.0) |

Diabetes (5.3%) Hypertension (8.7%) |

— |

CoronaVac BBIBP‐CorV WIBP‐CorV |

Neutralizing Ab | CLIA | >10 AU/ml | ≥2 weeks | — | 8 |

| HC | 144 | NA | Median: 35.0 (IQR 29.0–42.0) | NA | |||||||||

| Boyarsky 2021 19 | LT | 129 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

mRNA‐1273 BNT162B2 |

Anti‐spike Ab | ECLIA | ≥0.80 U/ml | Median: 29 days (IQR 28–31) | NA | 6 |

| Cholankeril 2022 20 | LT | 69 | 69.6% | Median: 63.0 (IQR 51.0–68.0) | Diabetes (48%) | Median: 3.3 (IQR 1.7–8.3) | BNT162B2 (100%) | Anti‐spike Ab | ELISA | Titre >20.0 | Range 30–75 days | MMF (36%); tacrolimus (90%); two agents (36%); three agents (12%) | 6 |

| Davidov 2022 21 | LT | 76 | 56.6% | 59.0 ± 15.0 | CKD (35.2%); diabetes (42%); hypertension (48.6%) | Median:7.0 (IQR 4.0–16.0) | BNT162B2 (100%) | Anti‐spike RBD Ab | ELISA | Titre >1.1 | 38 ± 24 days | MMF (21.3%); CNI monotherapy (53%); everolimus (14.7%); prednisone (16%); two agents (41%); three agents (5.3%) | 8 |

| HC | 174 | 49.4% | 59.0 ± 13.0 | — | 36 ± 22 days | — | |||||||

| Fernández‐Ruiz 2021 22 | LT | 13 | NA | NA | NA | NA | mRNA‐1273 (100%) | Anti‐spike Ab | ELISA | OD value ≥1.1 | 2 weeks | Tacrolimus monotherapy; two agents; three agents | 6 |

| Guarino 2022 23 | LT | 365 | 76.4% | 62.5 ± 13.0 | NA | 14.08 ± 8.84 | BNT162B2 (100%) | Anti‐spike Ab | CLIA | >25 AU/ml | 4 weeks | CNI (81.9%); steroid (7.6%); antimetabolite (36.2%); mTOR inhibitor (23.3%); single agent (59.7%); ≥two agents (40.3%) | 6 |

| HC | 340 | 64.1% | 57.9 ± 8.3 | — | — | — | |||||||

| He 2022 24 | CLD (cirrhosis 13.3%) | 362 | 61.6% | Median: 45.0 (range 19–78) | NA | — |

CoronaVac BBIBP‐CorV |

Anti‐spike RBD Ab | ELISA | OD value ≥2.1 | 1, 2 and 3 months | — | 7 |

| HC | 87 | 50.6% | Median: 44.0 (range 25–75) | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Herrera 2021 25 | LT | 58 | 69.0% | Median: 61.5 (IQR 18–88) |

CKD (26%) Lymphopenia (20.7%) Hypogammaglobulinemia (14%) |

Median: 4.6 (IQR 0.3–26.8) | mRNA‐1273 (100%) | Anti‐spike RBD Ab | CLIA | NA | 4 weeks | CNI (91%); MMF (26%); prednisone (22%); mTOR inhibitor (22%); monotherapy (47%); two agents (40%); three agents (12%) | 6 |

| Huang 2022 26 | LT | 274 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

mRNA‐1273 BNT162B2 |

Anti‐spike Ab | ELISA | Titre >1:50 | Median: 63 days (IQR 53–77) | CNI; antimetabolites; mTOR inhibitor | 6 |

| CLD | 76 | NA | NA | NA | — |

_ — |

|||||||

| Marion 2021 27 | LT | 58 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

mRNA‐1273 BNT162B2 |

Anti‐spike Ab | ELISA | NA | 4 weeks | CNI; MMF; mTOR inhibitor; steroid | 5 |

| Mazzola 2022 28 | LT | 56 | 76.8% | Median: 64.0 (IQR 58.0–68.2) |

Diabetes (41.4%) Pulmonary diseases (3.4%) Cardiovascular disease (44.8%) |

Median: 2.2 (IQR 1.3–4.9) |

BNT162B2 (100%) | Anti‐spike RBD Ab | CLIA | ≥50 AU/ml | 4 weeks | CNI (77.6%); MMF (56.9%); steroid (25.9%); mTOR inhibitor (22.4%) | 5 |

| HC | 25 | 28.0% | Median: 55.0 (IQR 38.0–62.0) | — | — | — | |||||||

| Rabinowich 2021 29 | LT | 80 | 70% | 60.1 ± 12.8 |

Diabetes (32.5%) Hypertension (56.2%) |

Median: 5 (range 0.42–37) | BNT162B2 (100%) | Anti‐spike Ab | CLIA | ≥15 AU/ml | 14.8 ± 3.2 days | CNI (93.7%); MMF (50%); prednisone (30%); everolimus, (22.5%); azathioprine (5%) | 5 |

| HC | 25 | 32% | 52.7 ± 11.5 | — | — | 15.8 ± 2.9 days | — | ||||||

| Rashidi‐Alavijeh 2021 30 | LT | 43 | 60.5% | NA | NA | Median: 8 (IQR 4–12) | BNT162B2 (100%) | Anti‐spike Ab | CLIA | ≥13 AU/ml | Median: 15 days (IQR 12–24) | MMF (28%); tacrolimus (93%); tacrolimus monotherapy (18%); tacrolimus+everolimus (55%); tacrolimus+cyclosporine A (5%); everolimus (2%) | 6 |

| HC | 20 | 45% | NA | — | — | 13 days | — | ||||||

| Ruether 2022 31 | LT | 138 | 27.2% | 55.0 ± 13.2 |

Diabetes (21.0%) Hypertension (61.6%) |

Median: 7 (IQR 2–17) |

mRNA‐1273 (8%) BNT162B2 (79.7%) AZD1222 (12.3%) |

Anti‐spike RBD Ab | ECLIA | ≥0.80 U/mL | Median: 29 days (IQR 25–39) | CNI (92.8%); CNI monotherapy (23.9%); prednisone (31.2%); CNI + prednisone (13.8%); CNI + mTOR inhibitor (12.3%); CNI + MMF (34.8%); CNI + azathioprine (6.5%); biologicals (5.8%); ≥three agents (13%) | 8 |

| CLD (cirrhosis 100%) | 48 | 60.4% | 53.8 ± 9.5 |

Diabetes (25.0%) Hypertension (37.5%) |

NA |

mRNA‐1273 (12.4%) BNT162B2 (79.2%) AZD1222 (8.4%) |

Median: 28 days (IQR 21–41) | — | |||||

| HC | 52 | 36.5% | 50.9 ± 11.6 | — | — |

mRNA‐1273 (5.8%) BNT162B2 (69.2%) AZD1222 (25%) |

Median: 49 days (IQR 28–74) | — | |||||

| Strauss 2021 32 | LT | 161 | 42.9% |

Median: 64.0 (IQR 48.0–69.0) |

NA | Median: 6.9 (IQR 2.9–15.0) |

mRNA‐1273 (47%) BNT162B2 (53%) |

Anti‐spike RBD Ab | ECLIA | ≥0.80 U/ml | Median: 30 days (IQR 28–31) | MMF (35%); tacrolimus (81%); steroid (22%); sirolimus (11%); cyclosporine (8%); azathioprine (6%); everolimus (3%) | 5 |

| Thuluvath 2021 33 | LT | 62 | 66.1% | 65.7 ± 8.7 |

COPD (13%) Hypertension (81.0%) Hyperlipidemia (56%) Renal impairment (65%) Coronary artery disease (19%) |

NA |

mRNA‐1273 (53%) BNT162B2 (39%) JNJ‐78436735 (8%) |

Anti‐spike RBD Ab | ECLIA | ≥0.4 U/ml | 38.9 ± 19.6 days | Azathioprine (3%); prednisone (13%); tacrolimus (66%) | 6 |

| CLD (cirrhosis 79%) | 171 | 45.0% | 60.4 ± 13.9 |

COPD (8.2%) Hypertension (63.7%) Hyperlipidemia (57.3%) Renal impairment (14.6%) Coronary artery disease (12.3%) |

— |

mRNA‐1273 (52%) BNT162B2 (39%) JNJ‐78436735 (9%) |

40.9 ± 23.9 days | Azathioprine (10%); prednisone (13%) | |||||

| Timmermann 2021 34 | LT | 118 | 63.6% | Mean: 66.1 (range 28–89) | NA | Mean: 14.4 (range 0–37) |

BNT162b2 (96.7%) mRNA‐1273 (2.5%) JNJ‐78436735 (0.8%) |

Anti‐spike Ab | ELISA | NA | Mean: 44.6 days (range 21–132) | MMF monotherapy (13.6%); tacrolimus monotherapy (35.6%); tacrolimus+MMF (20.3%); tacrolimus+everolimus (12.7%); everolimus monotherapy (0.8%); ciclosporin+MMF (2.5%); ciclosporin monotherapy (1.7%); tacrolimus+Azathioprine (0.8%) | 5 |

| Wang 2021 35 | NAFLD | 381 | 47.0% | Median: 39 (IQR 33–48) |

Diabetes (3.7%) Hypertension (11%) |

— | BBIBP‐CorV (100%) | Neutralizing Ab | CLIA | NA | 2 weeks | — | 6 |

| Xiang 2021 36 | CLD | 149 | 72.5% | Median: 41 (IQR 33–49) |

COPD (0.7%) Diabetes (2.7%) Hypertension (0.6%) Cardiovascular disease (1.3%) |

— |

CoronaVac BBIBP‐CorV WIBP‐CorV |

Anti‐spike RBD Ab | CLIA | >1 AU/ml | Median: 33 days (IQR 24–48) | — | 7 |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; CLD, chronic liver disease; CLIA, chemiluminescence analysis; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECLIA, electrochemiluminescence immunoassay analyser; ELISA, enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay; HC, healthy controls; IQR, interquartile range; LT, liver transplantation; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NA, not available; NAFLD, non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa scale; OD, optical density; RBD, receptor binding domain; SD, standard deviation.

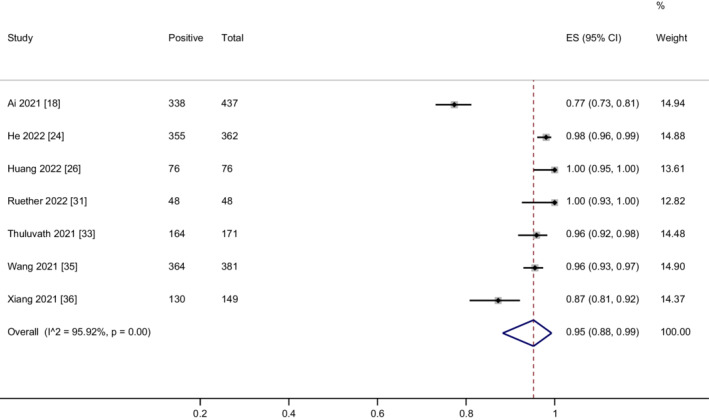

3.2. Humoral immune responses after two doses of vaccination in chronic liver disease patients

Seven studies 18 , 24 , 26 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 assessed the humoral immune responses after two doses of vaccination in CLD patients. As shown in Figure 2, the overall proportion of all included CLD patients achieving humoral immune responses was 95% (95% CI = 88%–99%) with considerable heterogeneity (I 2 = 95.9%, p < .01). Sensitivity analysis showed that the removal of Ai's and Xiang's studies 18 , 36 reduced the heterogeneity (I 2 = 63.7%, p = .03). The corresponding pooled humoral immune response rate was not changed markedly (98%, 95% CI = 96%–99%) (Figure S1). In addition, we compared the humoral immune responses in cirrhosis patients and non‐cirrhotic CLD patients. There was no significant difference in the humoral immune response rate between cirrhosis and non‐cirrhotic CLD patients (RR = 0.99; 95% CI = 0.96–1.03) without heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%, p = .66) (Figure S2).

FIGURE 2.

Meta‐analysis of the humoral immune responses after two doses of COVID‐19 vaccination in CLD patients.

3.3. Subgroup analysis

We performed a subgroup analysis based on whether or not patients had cirrhosis. The rates of humoral immune responses were 94% (95% CI = 82%–100%) and 94% (95% CI = 86%–99%) in the cirrhosis and in the non‐cirrhotic CLD patients respectively (Figure S3).

We performed a subgroup analysis based on the vaccine platform. The rates of humoral immune responses were 91% (95% CI = 79%–98%) and 99% (95% CI = 95%–100%) in inactivated vaccines and mRNA vaccines respectively (Figure S4).

We performed a subgroup analysis based on the assay of antibody testing. The rates of humoral immune responses were 88% (95% CI = 73%–97%), 99% (95% CI = 97%–100%), and 97% (95% CI = 95%–99%) in CLIA, ELISA and ECLIA respectively (Figure S5).

We performed a subgroup analysis based on the time interval between second vaccination and antibody measurement. The rates of humoral immune responses were 93% (95% CI = 77%–100%) and 96% (95% CI = 91%–100%) in ≤4 weeks and >4 weeks respectively (Figure S6).

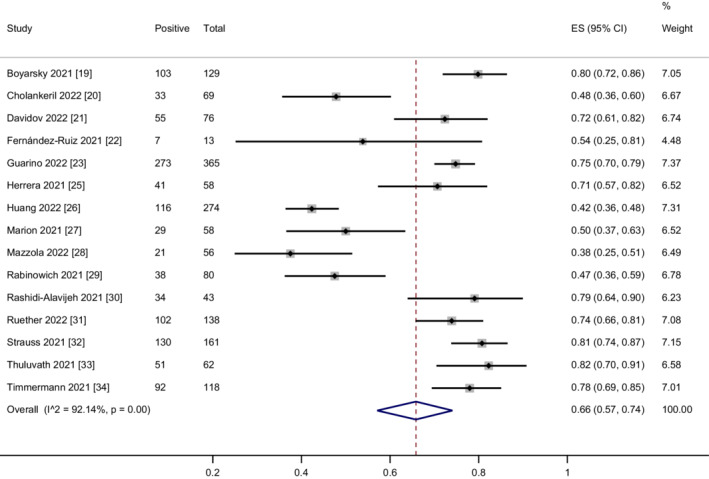

3.4. Humoral immune responses after two doses of vaccination in liver transplant recipients

Fifteen studies 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 assessed the humoral immune responses after two doses of vaccination in LT recipients. The overall proportion of patients achieving humoral immune responses was 66% (95% CI = 57%–74%) with considerable heterogeneity (I 2 = 92.1%, p < .01) (Figure 3). The funnel plot showed no publication bias (Egger's test p = .77, Begg's test p = .13) (Figure S7). We performed a sensitivity analysis by removing three studies 31 , 33 , 34 including adenovirus vector vaccines. The heterogeneity did not decrease after removing the three studies. The corresponding pooled humoral immune response rate hardly changed (62%, 95% CI = 52%–72%) (Figure S8). We found that the heterogeneity was mainly derived from six studies. 20 , 22 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 The exclusion of these studies effectively removed the heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%, p = .57), but the corresponding pooled humoral immune response rate was not changed markedly after the removal of these studies (77%, 95% CI = 74%–79%) (Figure S9). Removing one study at a time also showed that the removal of any individual study had little effect on the pooled rate, indicating that the result was stable.

FIGURE 3.

Meta‐analysis of the humoral immune responses after two doses of COVID‐19 vaccination in LT recipients.

3.5. Subgroup analysis

We performed a subgroup analysis based on the vaccine type. The rates of humoral immune responses were 64% (95% CI = 41%–84%), 61% (95% CI = 46%–74%), 68% (95% CI = 56%–79%), 74% (95% CI = 66%–81%) and 80% (95% CI = 73%–85%) in mRNA‐1273+BNT162B2, BNT162B2, mRNA‐1273, mRNA‐1273+BNT162B2+AZD1222 and mRNA‐1273+BNT162B2+JNJ‐78436735 respectively (Figure S10).

We performed a subgroup analysis based on the assay of antibody testing. The rates of humoral immune responses were 79% (95% CI = 75%–82%), 58% (95% CI = 43%–72%) and 63% (95% CI = 47%–77%) in ECLIA, ELISA and CLIA respectively (Figure S11).

We performed a subgroup analysis based on the time interval between second vaccination and antibody measurement. The rates of humoral immune responses were 70% (95% CI = 55%–83%) and 62% (95% CI = 51%–73%) in >4 weeks and ≤4 weeks respectively (Figure S12).

3.6. Risk factors for poor antibody responses in liver transplant recipients

Six studies 20 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 33 performed a univariate or multivariate analysis of the risk for negative serology in LT recipients. When more than two studies investigated a risk factor, the pooled OR with 95% CI was used to calculate the pooled effect estimate of risk factor for poor antibody responses. Totally, our results revealed that mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) (OR = 3.27, 95% CI = 1.45–7.41), diabetes (OR = 2.75, 95% CI = 1.48–5.09) and more than two immunosuppressants (OR = 3.13, 95% CI = 1.22–7.99) were risk factors for poor antibody responses in LT recipients. Parameters investigated by univariate or multivariate analysis as potential risk factors for poor antibody responses and results of meta‐analysis were summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Potential risk factors for poor antibody responses

| Risk factor | Number of included studies | Pooled OR/OR | 95% CI | I 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMF | 3 25 , 29 , 31 | 3.27 | 1.45–7.41 | 65.0% |

| Diabetes | 2 28 , 31 | 2.75 | 1.48–5.09 | 0% |

| ≥2 immunosuppressants | 4 20 , 29 , 31 , 33 | 3.13 | 1.22–7.99 | 80.1% |

| Age | 4 20 , 25 , 29 , 31 | 1.08 | 0.98–1.20 | 74.9% |

| Time since transplant | 4 20 , 25 , 29 , 31 | 2.54 | 0.93–6.95 | 78.5% |

| eGFR | 2 29 , 31 | 2.53 | 0.23–27.38 | 93.5% |

| Obesity | 2 20 , 31 | 1.86 | 0.36–9.66 | 79.2% |

| Hypertension | 1 31 | 2.62 | 1.28–5.37 | NA |

| High dose prednisone | 1 29 | 1.8 | 1.58–4.61 | NA |

| Time from second vaccination to antibody test | 1 20 | 1.01 | 0.96–1.04 | NA |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 1 25 | 61 | 3.70–1004.30 | NA |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; NA, not available; OR, odds ratio.

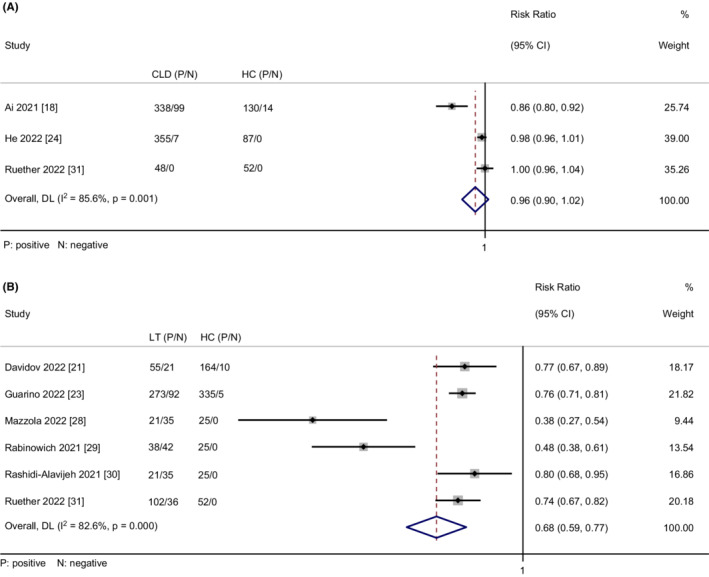

3.7. Comparison of humoral immune responses between patients and healthy controls

Three studies 18 , 24 , 31 assessed the humoral immune responses after two doses of vaccination in CLD patients in comparison with healthy controls. There was no statistically significant difference in the humoral immune response rate between CLD patients and healthy controls (RR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.90–1.02) with considerable heterogeneity (I 2 = 85.6%, p < .01) (Figure 4A). The meta‐analysis result was not changed markedly (RR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.97–1.01) without heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%, p = .53) by removing Ai's study, 18 indicating that the result was stable (Figure S13).

FIGURE 4.

(A) Meta‐analysis of comparison of the humoral immune responses between CLD patients and healthy controls. (B) Meta‐analysis of comparison of the humoral immune responses between LT recipients and healthy controls.

Six studies 21 , 23 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 compared the humoral immune responses after two doses of vaccination between LT recipients and healthy controls. Meta‐analysis of the six studies demonstrated that a significantly smaller proportion of LT recipients achieved humoral immune responses compared to healthy controls (RR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.59–0.77) with considerable heterogeneity (I 2 = 82.6%, p < .01) (Figure 4B). The rate of humoral immune response in LT recipients was still lower than healthy controls after removing two studies 28 , 29 (RR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.73–0.80) with no heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%, p = .90) (Figure S14). Additionally, we found that the RR value was not changed markedly after the removal of any one study, confirming the result's stability.

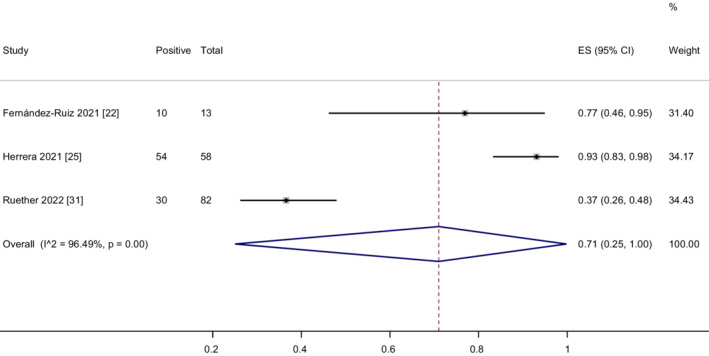

3.8. Cellular immune responses after two doses of vaccination

Three studies 22 , 25 , 31 assessed the cellular immune responses after two doses of vaccination in LT recipients. The overall proportion of patients achieving cellular immune responses was 71% (95% CI = 25%–100%) with considerable heterogeneity (I 2 = 96.5%, p < .01) (Figure 5). The heterogeneity was effectively decreased after the exclusion of Ruether's study 31 (I 2 = 43.6%, p = .18). In addition, the corresponding pooled cellular immune response rate was increased (92%, 95% CI = 83%–98%) (Figure S15). We did not perform the meta‐analysis of the cellular immune responses in CLD patients as only Ruether's study reported this result. In Ruether's study, the rates of cellular immune response were 36.6%, 65.4% and 100% in LT recipients, CLD patients and healthy controls respectively.

FIGURE 5.

Meta‐analysis of the cellular immune responses after two doses of COVID‐19 vaccination in LT recipients.

3.9. Grading the quality of evidence

According to the GRADE approach, the overall quality of evidence was low, as all the data were from observational studies (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) criteria for studies included in the meta‐analysis assessing the immunogenicity after two doses of COVID‐19 vaccines

| Outcome | No. of participants | Starting level of evidence | Quality assessment | Reasons to increase level of evidence (large magnitude of effect; dose–response gradient; potential confounding) | Overall quality of evidence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | |||||

| CLD | |||||||||

| Pool rate of HIR | 1624 | Low | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not applicable | Low |

| HIR (cirrhosis vs. non‐cirrhotic CLD) |

282 (cirrhosis) 690 (non‐cirrhotic CLD) |

Low | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not applicable | Low |

| HIR (CLD vs. HC) |

847 (CLD) 283 (HC) |

Low | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not applicable | Low |

| LT | |||||||||

| Pool rate of HIR | 1700 | Low | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not applicable | Low |

| Pool rate of CIR | 153 | Low | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not applicable | Low |

| HIR (LT vs. HC) |

758 (LT) 636 (HC) |

Low | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not applicable | Low |

Abbreviations: CIR, cellular immune response; CLD, chronic liver disease; HC, healthy controls; HIR, humoral immune response; LT, liver transplantation.

4. DISCUSSION

We performed this meta‐analysis of currently available observational studies to assess the immunogenicity of COVID‐19 vaccines in CLD patients and LT recipients. We demonstrated that two doses of COVID‐19 vaccination appeared to induce a strong humoral immune response in CLD patients. However, the rate of humoral immune response was low in LT recipients. Moreover, a significantly lower proportion of LT recipients achieved humoral immune responses after two doses of vaccination compared with healthy controls.

Our results indicated that the humoral immune responses to COVID‐19 vaccines did not appear to be impaired in CLD patients. These findings are very interesting, which is inconsistent with clinical phenomenon and previous study, where CLD patients especially those with cirrhosis, have reduced humoral immune responses to other vaccines such as HBV vaccines. 37 The included studies have demonstrated that older age, high body mass index, renal impairment, diabetes and compensation status in CLD patients are associated with immunosuppressive status, which can contribute to the decreased immune responses to COVID‐19 vaccines. 18 , 33 , 35 However, in the included studies 18 , 31 , 35 most patients were young. Moreover, obesity, diabetes and renal insufficiency were observed only in a small number of patients. These suggest that the majority of CLD patients in the included studies were not severely immunocompromised, which might explain the high seroconversion rate. Another potential reason for the high seroconversion rate may be related to the use of mRNA vaccines. Variability of antibody production among vaccinated populations may be related to the vaccine types, which may lead to different initial immune responses. 38 As the first mRNA vaccines used in humans, the SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccines use the synthesis mechanism of host cells to produce SARS‐CoV‐2 antigen, thereby triggering strong immune responses. 39 , 40 , 41 The previous studies found that compared with other types of vaccines, mRNA vaccines were more likely to cause seroconversion. 42 , 43 , 44 In this study, seven studies 18 , 24 , 26 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 explored the humoral immune responses after vaccination in CLD patients. Three 26 , 31 , 33 of seven studies used mRNA vaccines and four 18 , 24 , 35 , 36 used inactivated vaccines. Our meta‐analysis showed that the rate of seroconversion to mRNA vaccines was higher than in inactivated vaccines (99% vs. 91%).

Patients with cirrhosis are considered more severely immunocompromised than non‐cirrhotic CLD patients. However, in the subgroup analysis, we observed similar humoral immune responses in cirrhosis and non‐cirrhotic CLD patients, consistent with He's and Thuluvath's studies. 24 , 33 Thuluvath's study found cirrhosis was not associated with a poor antibody response after COVID‐19 vaccination using multivariate analysis.

Regarding the humoral immune response, our meta‐analysis results showed that 68% of LT recipients achieved seroconversion after two doses of vaccination. Moreover, we also found that the humoral immune responses were reduced in LT patients compared with healthy controls, which is in line with previous studies. 21 , 23 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 Our results indicated that MMF and more than two immunosuppressants were risk factors related to poor antibody responses. These immunosuppressive regimens can greatly suppress the patient's immune status, resulting in poor antibody responses to vaccines. Many studies 29 , 31 , 33 have demonstrated that treatment with MMF or more than two immunosuppressants can decrease the immune responses to COVID‐19 vaccines, consistent with the findings in solid organ transplant recipients. 45 , 46 LT patients who received the MMF show a lower seroconversion rate (45.5%–61%) in comparison with those without the MMF (79%–81%). 30 , 32 Diabetes is common among transplant recipients, notably as a complication of the transplant immunosuppressive therapy (steroids and calcineurin inhibitors). In the present study, our meta‐analysis result showed diabetes is an independent risk factor for poor humoral immune response. This is also consistent with previous studies suggesting that seasonal influenza vaccination uptake remains suboptimal in patients with diabetes probably due to immune dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus. 47 , 48

It has been found that, despite a lack of seroconversion, the T‐cell response may protect an individual against the SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 49 Thus, the T‐cell response should be examined after vaccination to assist in the determination of vaccine effectiveness. In the present study, only three studies 22 , 25 , 31 reported the cellular immune responses to vaccination. The result of meta‐analysis showed that the cellular immune responses in LT recipients were still low with considerable heterogeneity. After removing Rueher's study, 31 the rate of cellular immune response was increased significantly to 92% without heterogeneity, which indicated the instability of this result. We found clinically heterogeneous participants and different immunosuppressive regimens could be the main source of heterogeneity. Although some studies suggest a decrease in cellular immune response after vaccination in immunocompromised patients, more studies are needed to confirm this conclusion in CLD patients and LT recipients.

The present study has some limitations. Firstly, most included studies only evaluated humoral responses to COVID‐19 vaccines, and data on the cellular immune responses to COVID‐19 vaccines are still lacking. Secondly, it is important to emphasize that the included studies are observational and have potential sources of bias, such as selection bias or confounding, that cannot be adjusted by meta‐analysis.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that COVID‐19 vaccination elicited strong humoral responses in CLD patients but poor humoral immune responses in LT recipients. The findings indicate that CLD patients and LT recipients should complete the full vaccine schedule without delay and support the administration of a third dose of vaccine to LT recipients. With both the appearance of novel variants of the virus and waning antibody responses, further studies assessing the immunogenicity and effectiveness of different types of vaccines and updated living meta‐analyses are warranted.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors do not have any disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Figure S1

Figure S2

Figure S3

Figure S4

Figure S5

Figure S6

Figure S7

Figure S8

Figure S9

Figure S10

Figure S11

Figure S12

Figure S13

Figure S14

Figure S15

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Wanjie Gu for his help in statistical analysis.

Luo D, Chen X, Du J, et al. Immunogenicity of COVID‐19 vaccines in chronic liver disease patients and liver transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Liver Int. 2022;00:1‐15. doi: 10.1111/liv.15403

Handling Editor: Dr. Alejandro Forner

De Luo, Xinpei Chen and Juan Du have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Uta Dahmen, Email: uta.dahmen@med.uni-jena.de.

Bo Li, Email: liboer2002@swmu.edu.cn.

Su Song, Email: susong1978@swmu.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507‐513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Piano S, Brocca A, Mareso S, et al. Infections complicating cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2018;38(suppl 1):126‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Albillos A, Lario M, Álvarez‐Mon M. Cirrhosis associated immune dysfunction: distinctive features and clinical relevance. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1385‐1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marjot T, Moon AM, Cook JA, et al. Outcomes following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in patients with chronic liver disease: an international registry study. J Hepatol. 2021;74(3):567‐577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sarin SK, Choudhury A, Lau GK, et al. Pre‐existing liver disease is associated with poor outcome in patients with SARS CoV2 infection; the APCOLIS study (APASL COVID‐19 liver injury Spectrum study). Hepatol Int. 2020;14(5):690‐700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iavarone M, D'Ambrosio R, Soria A, et al. High rates of 30‐day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and COVID‐19. J Hepatol. 2020;73(5):1063‐1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Di Maira T, Berenguer M. COVID‐19 and liver transplantation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:526‐528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sahin TT, Akbulut S, Yilmaz S. COVID‐19 pandemic: its impact on liver disease and liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:2987‐2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Forni G, Mantovani A. COVID‐19 vaccines: where we stand and challenges ahead. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:626‐639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stuart A, Shaw R, Liu X, et al. Immunogenicity, safety, and reactogenicity of heterologous COVID‐19 primary vaccination incorporating mRNA, viral‐vector, and protein‐adjuvant vaccines in the UK (com‐COV2): a single‐blind, randomised, phase 2, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet. 2022;399:36‐49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosenberg E, Dorabawila V, Easton D, et al. Covid‐19 vaccine effectiveness in New York state. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:116‐127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Booth A, Clarke M, Ghersi D, et al. An international registry of systematic‐review protocols. Lancet. 2011;377:108‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta‐analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence‐‐study limitations (risk of bias). J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:407‐415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557‐560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:Ed000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ai J, Wang J, Liu D, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines in patients with chronic liver diseases (CHESS‐NMCID 2101): a multicenter study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;20:1516‐1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boyarsky BJ, Werbel WA, Avery RK, et al. Antibody response to 2‐dose SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccine series in solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA. 2021;325:2204‐2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cholankeril G, Al‐Hillan A, Tarlow B, et al. Clinical factors associated with lack of serological response to SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccine in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2022;28:123‐126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Davidov Y, Tsaraf K, Cohen‐Ezra O, et al. Immunogenicity and adverse effect of two dose BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine among liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2022;28:215‐223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fernández‐Ruiz M, Almendro‐Vázquez P, Carretero O, et al. Discordance between SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific cell‐mediated and antibody responses elicited by mRNA‐1273 vaccine in kidney and liver transplant recipients. Transplant Direct. 2021;7:e794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guarino M, Cossiga V, Esposito I, et al. Effectiveness of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in liver transplanted patients: the debate is open! J Hepatol. 2022;76:237‐239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. He T, Zhou Y, Xu P, et al. Safety and antibody response to inactivated COVID‐19 vaccine in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Liver Int. 2022;42:1287‐1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Herrera S, Colmenero J, Pascal M, et al. Cellular and humoral immune response after mRNA‐1273 SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in liver and heart transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:3971‐3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang HJ, Yi SG, Mobley CM, et al. Early humoral immune response to two doses of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccine in a diverse group of solid organ transplant candidates and recipients. Clin Transplant. 2022;36:e14600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marion O, Del Bello A, Abravanel F, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 messenger RNA vaccines in recipients of solid organ transplants. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1336‐1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mazzola A, Todesco E, Drouin S, et al. Poor antibody response after two doses of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74:1093‐1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rabinowich L, Grupper A, Baruch R, et al. Low immunogenicity to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination among liver transplant recipients. J Hepatol. 2021;75:435‐438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rashidi‐Alavijeh J, Frey A, Passenberg M, et al. Humoral response to SARS‐Cov‐2 vaccination in liver transplant recipients‐a single‐center experience. Vaccine. 2021;9:738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ruether DF, Schaub GM, Duengelhoef PM, et al. SARS‐CoV2‐specific humoral and T‐cell immune response after second vaccination in liver cirrhosis and transplant patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:162‐172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Strauss AT, Hallett AM, Boyarsky BJ, et al. Antibody response to severe acute respiratory syndrome‐Coronavirus‐2 messenger RNA vaccines in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2021;27:1852‐1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thuluvath PJ, Robarts P, Chauhan M. Analysis of antibody responses after COVID‐19 vaccination in liver transplant recipients and those with chronic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2021;75:1434‐1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Timmermann L, Globke B, Lurje G, et al. Humoral immune response following SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in liver transplant recipients. Vaccine. 2021;9(12):1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang J, Hou Z, Liu J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of COVID‐19 vaccination in patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (CHESS2101): a multicenter study. J Hepatol. 2021;75:439‐441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xiang T, Liang B, Wang H, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a SARS‐CoV‐2 inactivated vaccine in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:2679‐2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aggeletopoulou I, Davoulou P, Konstantakis C, et al. Response to hepatitis B vaccination in patients with liver cirrhosis. Rev Med Virol. 2017;27:e1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yen JS, Wang IK, Yen TH. COVID‐19 vaccination and dialysis patients: why the variable response. QJM. 2021;114(7):440‐444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Woldemeskel BA, Garliss CC, Blankson JN. SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccines induce broad CD4+ T cell responses that recognize SARS‐CoV‐2 variants and HCoV‐NL63. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e149335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Turner JS, O'Halloran JA, Kalaidina E, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccines induce persistent human germinal Centre responses. Nature. 2021;596:109‐113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lederer K, Castaño D, Gómez Atria D, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccines Foster potent antigen‐specific germinal center responses associated with neutralizing antibody generation. Immunity. 2020;53:1281‐1295.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Garcia P, Anand S, Han J, et al. COVID‐19 vaccine type and humoral immune response in patients receiving dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33:33‐37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lim WW, Mak L, Leung GM, et al. Comparative immunogenicity of mRNA and inactivated vaccines against COVID‐19. The Lancet Microbe. 2021;2:e423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ozakbas S, Baba C, Dogan Y, et al. Comparison of SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody response after two doses of mRNA and inactivated vaccines in multiple sclerosis patients treated with disease‐modifying therapies. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;58:103486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Malinis M, Cohen E, Azar MM. Effectiveness of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in fully vaccinated solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:2916‐2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Caillard S, Thaunat O. COVID‐19 vaccination in kidney transplant recipients. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021;17:785‐787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yang L, Nan H, Liang J, et al. Influenza vaccination in older people with diabetes and their household contacts. Vaccine. 2017;35:889‐896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jiménez‐Garcia R, Lopez‐de‐Andres A, Hernandez‐Barrera V, et al. Influenza vaccination in people with type 2 diabetes, coverage, predictors of uptake, and perceptions. Result of the MADIABETES cohort a 7years follow up study. Vaccine. 2017;35:101‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Toor SM, Saleh R, Sasidharan Nair V, et al. T‐cell responses and therapies against SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Immunology. 2021;162:30‐43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1

Figure S2

Figure S3

Figure S4

Figure S5

Figure S6

Figure S7

Figure S8

Figure S9

Figure S10

Figure S11

Figure S12

Figure S13

Figure S14

Figure S15

Table S1