Acetaminophen has been available as an enteral or rectal formulation for the past two decades. After that, an intravenous (i.v.) formulation was approved in 2002 in Europe, in 2010 in the USA and in 2016 in Japan. Although i.v. administration of acetaminophen is expected to have better bioavailability than rectal or oral administration, recent data are inconsistent with i.v. acetaminophen superiority for critical illness.1, 2 During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, acetaminophen was more frequently used for fever reduction. Although all formulations of acetaminophen are considered relatively safe, i.v. administration is associated with an increased risk of hypotension, particularly in older patients with a hemodynamically unstable status. 3

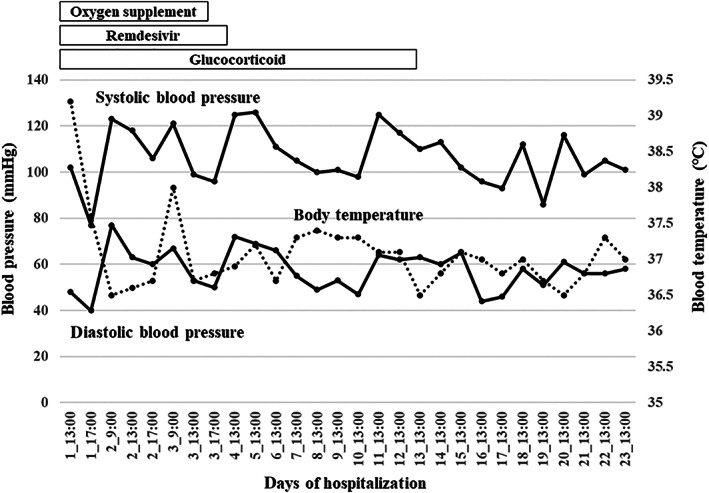

A woman aged in her 70s was diagnosed with COVID‐19 and transferred to our hospital (Oita University Hospital, Oita, Japan) because of persistent dyspnea for 3 days. She had several pre‐existing cardiovascular diseases, including patent foramen ovale and ventricular septal defect, and had undergone surgery for aortic dissection 3 years earlier. Physical examination showed a body temperature of 39.2°C, an oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 93% with supplemental oxygenation of 2 L/min, blood pressure of 102/48 mmHg, heart rate of 92 b.p.m. and impaired consciousness with the Glasgow Coma Scale of E3V4M6. Laboratory tests showed a normal leukocyte count and an elevated serum C‐reactive protein level (9.77 mg/dL). Chest images showed ground‐glass opacities predominantly in both lower lobes, which was consistent with COVID‐19 pneumonia. Approximately 4 h after admission, the patient's consciousness level deteriorated from Glasgow Coma Scale E3V4M6 to E2V3M5. Her systolic blood pressure dropped to 70 mmHg, whereas her body temperature decreased from 39.2°C to 37.6°C (Fig. 1). However, rash and mucosal edema were not observed. We rapidly administered an i.v. infusion of 1000 mL of Ringer's acetate solution and started noradrenaline because of the lack of hemodynamic response to the infusion. Her consciousness improved a few hours later as her systolic blood pressure gradually increased.

Figure 1.

The record of blood pressure and body temperature of the patient during hospitalization.

We assessed potential causes of impaired consciousness, including cerebrovascular diseases, but no abnormal finding was observed. Considering the recovery course, the hypotension mainly was suspected to decrease the consciousness level. Blood culture was negative, and a cardiovascular specialist ruled out cardiogenic hypotension. After a detailed medical history assessment, the patient was found to have received acetaminophen (500 mg) i.v. for fever reduction 30 min before the transfer to our hospital. Furthermore, she used to take acetaminophen (250 mg) orally for chronic headaches before COVID‐19 development, but she had not experienced any adverse effects. Indeed, no significant hypotension was observed when she took acetaminophen (250 mg) orally for headache 3 days after recovery from shock. As the hypotension occurred a few hours after acetaminophen administration, ruling out other potential causes, we suspected acetaminophen‐induced non‐anaphylactic shock. She was successfully treated and was discharged on day 25.

The patient had never been administered i.v. acetaminophen before, and hypotension was found approximately 5 h after infusion of acetaminophen. Acetaminophen‐induced hypotension appears to start within 15 min, and reaches a peak approximately 60–120 min after i.v. infusion. 4 Her blood pressure was slightly low on admission, but we failed to follow up on her blood pressure until her impaired consciousness was noted by medical staff. Although viral sepsis could not be entirely ruled out as a trigger of hypotension, it was unlikely, because the severity of COVID‐19 was moderate with a good clinical course.

Based on a systematic review, hypotension does not correlate with the total dose or infusion rate, i.v. infusion might be a significant risk, inducing adverse effects. 3 In a randomized control study, Kelly et al. showed that i.v., but not oral, administration was an independent predictor of hypotension. Patient background plays a role in predicting hemodynamic changes. Some studies found that advanced age,5, 6 lower baseline mean arterial pressure 7 and febrile illness 5 were associated with increased risk of hypotension. Furthermore, a history of cardiac surgery might contribute to acetaminophen‐induced blood pressure reduction. 8 As no direct effect of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 on vasodilation was determined, its infection did not appear to contribute to acetaminophen‐induced hypotension directly. However, the patient had several underlying cardiovascular diseases and experienced a high fever due to COVID‐19, which might have been associated with an increased risk of hypotension.

Acetaminophen is commonly used as an analgesic or antipyretic agent, even for older people. However, medical workers and patients should be aware of the potential risk of acetaminophen‐induced hypotension, and i.v. administration of acetaminophen needs to be avoided in high‐risk patients.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this manuscript and accompanying images.

Acknowledgements

None.

Masui R, Komiya K, Tanaka A, et al. Intravenous acetaminophen‐induced non‐anaphylactic shock in an older patient with COVID‐19. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2022;22:895–897. 10.1111/ggi.14474

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this case report are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2018; 46: e825–e873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Young P, Saxena M, Bellomo R et al. Acetaminophen for fever in critically ill patients with suspected infection. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2215–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maxwell EN, Johnson B, Cammilleri J, Ferreira JA. Intravenous acetaminophen‐induced hypotension: a review of the current literature. Ann Pharmacother 2019; 53: 1033–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Young TL. A narrative review of paracetamol‐induced hypotension: keeping the patient safe. Nurs Open 2021; 9: 1589–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bae JI, Ahn S, Lee YS et al. Clinically significant hemodynamic alterations after propacetamol injection in the emergency department: prevalence and risk factors. Intern Emerg Med 2017; 12: 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee HY, Ban GY, Jeong CG et al. Propacetamol poses a potential harm of adverse hypotension in male and older patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2017; 26: 256–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saxena MK, Taylor C, Billot L et al. The effect of paracetamol on Core body temperature in acute traumatic brain injury: a randomised, controlled clinical trial. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0144740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chiam E, Bellomo R, Churilov L, Weinberg L. The hemodynamic effects of intravenous paracetamol (acetaminophen) vs normal saline in cardiac surgery patients: a single center placebo controlled randomized study. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0195931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this case report are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.