Abstract

The aim of the study was to trace and understand the origin of Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) through various available literatures and accessible databases. Although the world enters the third year of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, health and socioeconomic impacts continue to mount, the origin and mechanisms of spill‐over of the SARS‐CoV‐2 into humans remain elusive. Therefore, a systematic review of the literature was performed that showcased the integrated information obtained through manual searches, digital databases (PubMed, CINAHL, and MEDLINE) searches, and searches from legitimate publications (1966–2022), followed by meta‐analysis. Our systematic analysis data proposed three postulated hypotheses concerning the origin of the SARS‐CoV‐2, which include zoonotic origin (Z), laboratory origin (L), and obscure origin (O). Despite the fact that the zoonotic origin for SARS‐CoV‐2 has not been conclusively identified to date, our data suggest a zoonotic origin, in contrast to some alternative concepts, including the probability of a laboratory incident or leak. Our data exhibit that zoonotic origin (Z) has higher evidence‐based support as compared to laboratory origin (L). Importantly, based on all the studies included, we generated the forest plot with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the risk ratio estimates. Our meta‐analysis further supports the zoonotic origin of SARS/SARS‐CoV‐2 in the included studies.

Keywords: COVID‐19, laboratory incidence, MERS‐CoV, origin, SARS‐CoV, SARS‐CoV‐2, zoonotic

1. INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) has been responsible for the global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic with at least 426 million cases and 5.89 million deaths reported to date. 1 Despite the ongoing emergence of different variants of SARS‐CoV‐2 with increased efficiency for human‐to‐human transmission, massive administration of various vaccines has succeeded in decreasing the global death rate. SARS‐CoV‐2 has spread worldwide since it was first discovered in Wuhan, China where its source of transmission to humans seems to be traced to a seafood wholesale market. 2

Previous epidemics caused by other coronaviruses (CoVs), such as the Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS‐CoV) in 2002 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV) in 2012, originated from bats and involved intermediate hosts. 3 To date, seven human coronaviruses do exist including human Coronavirus‐229E (HCoV‐229E), human Coronavirus‐OC43 (HCoV‐OC43), human Coronavirus‐NL63 (HCoV‐NL63), and human Coronavirus‐HKU1 (HCoV‐HKU1), SARS‐CoV, MERS‐CoV, and SARS‐CoV‐2. The former four coronaviruses are the most predominant types of human coronaviruses that cause the common cold. 4

Based on the currently available data, it remains unclear whether the inception of SARS‐CoV‐2 is the result of zoonosis caused by a wild viral strain or an accidental escape of experimental strains. It is critical to address this issue to develop preventive and biosafety measures. Indeed, the recent zoonosis can justify the need to obtain samples from natural ecosystems, farms, and breeding facilities to prevent spillover. On the contrary, a laboratory escape would necessitate a thorough re‐evaluation of the risk/benefit balance of various laboratory methods and the stringent implementation of biosafety standards. Several theories regarding the origin of SARS‐CoV‐2 are considered. The critical need to advance biosafety standards at all laboratory levels is paramount as experimental virology research on dangerous pathogens develops to reduce the threat of pandemics to the environment and human civilization. Therefore, in the present study, we have performed a systematic review, followed by meta‐analysis to decipher the origin of SARS‐CoV‐2.

2. METHODS

2.1. Literature search

A systematic review was performed by the sources listed in Supporting Information: Table S1. The sources used for the analysis were PUBMED searches (1966–2022), MEDLINE searches (2000–2022), and CINAHL searches (2000–2022). The major keywords used for indexing the databases were SARS, SARS‐CoV‐2, COVID‐19, coronaviruses, origin, virus, FCS (furin cleavage sites), spike proteins, bats, novel, and so forth (Supporting Information: Table S1). This was followed by elaborative discussions with the experts. Datasets available from NCBI were used for the authentic validation of data.

2.2. Clustering and similarity matrix analysis

Year‐wise clustergrams/heatmaps were generated to visualize the origin of SARS‐COV‐2 from different sources (Supporting Information: Table S1) specifically zoonotic origin (Z), laboratory origin (L), and obscure origin (O). The rows and columns were hierarchically clustered, using a cosine distance and an average linkage method where the included studies were clustered in rows. 5 Moreover, we generated the similarity matrix of these origin sources (Supporting Information: Table S1).

2.3. Forest plot analysis

A Forest plot was generated between Z and L origin using Cochrane's Review Manager (RevMan, version 5.4; Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark). The risk ratio (RR) at 95% confidence interval (CI), was calculated to estimate the ratio of the risk in the Z group to the risk in the L group.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Historical evidence of coronavirus

The HCoV‐229E was first discovered in the United Kingdom in 1966 6 followed by the discovery of HCoV‐OC43 in 1967 from a patient with respiratory distress in the United Kingdom. 7 , 8 The HCoV‐NL63 was isolated during the 2002‐to‐2003 winter season in the Netherlands, 9 and HKU1 was first reported in an individual from a large Chinese metropolis (Shenzhen, Guangdong) who developed pneumonia in the winter of 2004. 10 , 11 The SARS‐CoV was first detected in November 2002 in Foshan, China. 12 It has infected several people with 8447 cases and caused 813 deaths (9.6% case fatalities); it was contained in July 2003. 13 MERS‐CoV was first detected in Saudi Arabia in June 2012; however, neutralizing antibodies have been detected in archival serum samples from dromedary camels in Somalia and Sudan in 1983. 14 MERS‐CoV has been reported in 27 more countries in the Middle East, North Africa, Asia, Europe, and the United States 15 resulting in more than 2585 cases and 890 deaths (case‐fatality ratio of 34.4%) from the virus. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the Republic of Korea were the countries with the most outbreaks. 16 In comparison to females, a higher percentage of males (about 63%) were severely affected (approx. 37%). MERS‐CoV cases were recorded from nearly every region of the Middle East countries, while Riyadh (30%) and Jeddah (29%) alone accounted for nearly two‐thirds of the cases. 17 Later, in December 2019, SARS‐CoV‐2 has emerged in Wuhan, Hubei province, where cases of severe pneumonia were reported. 18 , 19 On March 11, 2020, SARS‐CoV‐2 was declared as the first ever coronavirus pandemic.

HCoV‐229E, HCoV‐NL63, SARS‐CoV, MERS‐CoV, and SARS‐CoV‐2 originated from ancestral bat CoVs, 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 whereas the rodent CoVs are the ancestral viruses of both HCoV‐OC43 and HCoV‐HKU1. 22 Camels are the current known intermediate animal host of both HCoV‐229E and MERS‐CoV. 26 , 27 Although HCoV‐OC43 showed antigenic similarity to bovine CoV suggests a relatively recent zoonotic transmission event that dates their most recent common ancestor to around 1890. 8 HCoV‐NL63 is assumed to be evolved by a recombination event of NL63‐like viruses and 229E‐like viruses circulating in bats 28 and a spillover from bats to humans is assumed to happen 563 to 822 years ago. 23 Meanwhile, both civet cats and raccoon dogs are possible intermediate hosts to the SARS‐CoV. 29 , 30 Although there is no current confirmed intermediate host for the SARS‐CoV‐2, pangolins were considered as the incriminated hosts 31 while HCoV‐HKU1 has an unknown animal origin. 11 SARS‐CoV‐2 exhibits several hallmarks of previous zoonotic outbreaks. It bears a striking resemblance to the SARS‐CoV, which infected many individuals in the Foshan (2002) and Guangzhou (2003) regions of China. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 The SARS‐CoV outbreaks in these two regions have resulted in a significant increase in the number of people infected with the virus. SARS‐CoV‐2 outbreaks have been associated with exposure to wet animal markets in Wuhan (2019), which may facilitate the transmission of this virus. 32

3.2. Significance of the Spike (S) protein of SARS‐CoV‐2

The S protein is a crucial glycoprotein involved in receptor binding and cell entry. The S protein is cleaved from two locations, S1/S2 and the S2′ site, following receptor engagement to promote virus entry into the cell. 32 According to preliminary structural studies, SARS‐CoV‐2 has a higher affinity for the angiotensin‐converting enzyme‐ 2 (ACE‐2) receptor than the original SARS‐CoV. 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 Both COVID‐19 patient sera and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against the receptor‐binding domain (RBD) had lower results in neutralization studies, including mutations. 40 These findings indicate the vital function of the furin‐like cleavage site (FCS) in the SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, as well as the potential pitfalls of interpreting the results of studies on this virus. The FCS deletion significantly affects virus neutralization by the sera collected from COVID‐19 patients by administering specific mAb against the SARS‐CoV‐2 RBD. Although each mAb targets a different location in the RBD, the wild type and mutant type exhibit equal reductions in mAb serum neutralization levels, indicating possible therapeutic approaches against SARS‐CoV‐2. 41

The S1/S2 furin sensitive proteolytic cleavage site appears to contribute to its infectivity in humans and may be related to its epidemic tendency. 42 This insertion is likely new because it is not found in any viruses related to SARS‐CoV‐2. Like SARS‐CoV‐2, HCoVOC43, HCoVHKU1 and MERSCoV possess furin cleavage site. 20 This finding is significant because this genetic characteristic is likely to be involved in bridging the species barrier and increasing the efficiency of human‐to‐human transmission, both of which are necessary for an epidemic to occur. Several laboratories are conducting and publishing gain‐of‐function (GoF) experiments to explore the association between coronavirus RBD and transmembrane receptors such as ACE2. 43 SARS‐CoV‐2 was postulated as the outcome of experiments to “humanize” an animal virus of the RaTG13 type, 44 but the scientific community has not presented persuasive proof to confirm this hypothesis.

3.3. Origin of SARS‐CoV‐2

The current understanding of SARS‐CoV‐2 origin is inconclusive. However, it is useful to consider whether conclusions can already be formed based on the available evidence and which of the recent findings or analysis would provide additional information to trace the origin of SARS‐CoV‐2. The first issue in tracing its origin is identification of primary animal hosts before the virus' transmission to humans. CoVs from chiropterans are often transmitted between bat species and are occasionally transmitted to other mammals, according to the results of a previous phylogenetic analysis. 45 Point mutations and recombination events, common in coronaviruses, are involved in virus co‐evolution with their hosts and adaptation to new hosts. 46 Because mosaicism biases the whole genome‐based phylogenetic inference, the resulting tree would reflect a blend of the diverse developmental pathways pursued by the different open reading frames (ORFs), which poses specific challenges. Hence, it is crucial to recognize the recombinant fragments and make different phylogenetic inferences for each of them. SARS‐CoV‐2 is thought to result from several recombination events among chiropteran CoVs, which are probably the principal reservoir of the virus. Because of its critical function in the interaction with the host ACE2 receptor and virus entry, the effect of recombination is very significant for the adaptability of the S protein. 47 Our systematic analysis proposes the following postulated hypothesis concerning the origin of the SARS‐CoV‐2. Bioinformatic studies may further help us to determine the origin of SARS‐CoV‐2.

3.3.1. Theories of SARS‐CoV‐2 origin

Zoonotic origin (Z)

Bats‐to‐man transmission

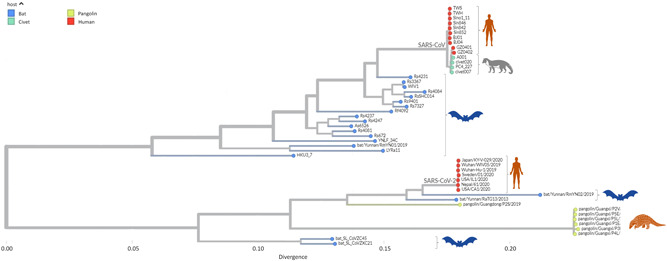

Bats were thought to be the original host when the first genomic material for SARS‐CoV‐2 was available. 41 Bat‐CoV‐RaTG13, a bat coronavirus isolated from Rhinolophus affinis, shares a 96% whole‐genome sequence identity with SARS‐CoV‐2. SARS‐CoV‐2 closely related viruses have been found in bats in Southeast Asia, including China, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos (e.g., BANAL‐52), and Japan. 48 , 49 However, there is a significant evolutionary gap between SARS‐CoV‐2 and the closest related animal viruses. For example, the bat virus RaTG13 obtained by the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) has a genetic distance of >4% (approximately 1150 mutations) from the SARS‐CoV‐2 Wuhan‐Hu‐1 reference sequence, implying the generations of developmental differences 31 (Figure 1). Moreover, two studies that analyzed the molecular spectrum of mutations also supported bats‐to‐man direct transmission and disputed the possibility of serial passage in mouse or human cell lines or chimeric coronaviruses. 50 , 51 Year wise SARS‐CoV‐2, SARS‐like coronaviruses, and SARS‐CoV‐2 isolates have been mentioned in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic of SARS‐like coronaviruses and SARS‐CoV‐2. Phylogenetic relationship showing that the SARS‐CoV‐2 is closely related to the SARS‐like coronaviruses isolated from the bats. However, SARS‐CoV‐2 has been reported in pangolins. Whereas earlier reported SARS‐CoV has been isolated from humans, bats, and civets. SARS‐CoV‐2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Table 1.

Year wise SARS‐CoV‐2, SARS‐like coronaviruses and SARS‐CoV‐2 isolates

| Virus type | Year | Sequence ID | Accession number | Host | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS‐CoV | 2003 | TWS | AP006560 | Human | Taiwan |

| SARS‐CoV | 2003 | TWH | AP006557 | Human | Taiwan |

| SARS‐CoV | 2003 | BJ01 | AY278488 | Human | China |

| SARS‐CoV | 2003 | BJ04 | AY279354 | Human | China |

| SARS‐CoV | 2004 | Sin846 | AY559094 | Human | Singapore |

| SARS‐CoV | 2004 | Sin842 | AY559081 | Human | Singapore |

| SARS‐CoV | 2005 | Sino1_11 | AY485277 | Human | China |

| SARS‐CoV | 2005 | GZ0401 | AY568539 | Human | China |

| SARS‐CoV | 2005 | GZ0402 | AY613947 | Human | China |

| SARS‐CoV | 2005 | Civet020 | AY572038 | Civet | China |

| SARS‐CoV | 2005 | PC4_227 | AY613950 | Civet | China |

| SARS‐CoV | 2005 | Civet007 | AY572034 | Civet | China |

| SARS‐CoV | 2009 | A001 | FJ959407 | Civet | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2010 | HKU3_7 | GQ153542 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2013 | RS3367 | KC881006 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2013 | WIV1 | KF367457 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2013 | RsSHC014 | KC881005 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2013 | bat/Yunnan/RaTG13/2013 | EPI_ISL_402131 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2014 | LYRa11 | KF569996 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2015 | YNLF_34C | KP886809 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2015 | bat_SL_CoVZXC21 | MG772934 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | RS4231 | KY417146 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | RS4084 | KY417144 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | Rs9401 | KY417152 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | Rs7327 | KY417151 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | Rf4092 | KY417145 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | Rs4237 | KY417147 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | Rs4247 | KY417148 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | As6526 | KY417142 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | Rs4081 | KY417143 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | Rs672 | KY417143 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | pangolin/Guangxi/P2V/2017 | EPI_ISL_410542 | Pangolin | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | pangolin/Guangxi/P5E/2017 | EPI_ISL_410541 | Pangolin | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | pangolin/Guangxi/P5L/2017 | EPI_ISL_410540 | Pangolin | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | pangolin/Guangxi/P1E/2017 | EPI_ISL_410539 | Pangolin | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | pangolin/Guangxi/P3B/2017 | EPI_ISL_410543 | Pangolin | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | pangolin/Guangxi/P4L/2017 | EPI_ISL_410538 | Pangolin | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2017 | bat_SL_CoVZC45 | MG772933 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2019 | Bat/Yunnan/RmYN01/2019 | EPI_ISL_412976 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 | 2019 | Wuhan/WIV05/2019 | MN996529 | Human | China |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 | 2019 | Wuhan‐Hu‐1/2020 | WH‐Human_1 | Human | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2019 | bat/Yunnan/RmYN02/2019 | EPI_ISL_412977 | Bat | China |

| SARS‐like CoV | 2019 | pangolin/Guangdong/P2S/2019 | EPI_ISL_410544 | Pangolin | China |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 | 2020 | Japan/KY‐V‐029/2020 | LC522972 | Human | Japan |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 | 2020 | Sweden/01/2020 | MT093571 | Human | Sweden |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 | 2020 | USA/IL1/2020 | MN988713 | Human | USA |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 | 2020 | Nepal/61/2020 | MT072688 | Human | Nepal |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 | 2020 | USA/CA1/2020 | MN994467 | Human | USA |

The widespread genome recombination makes it challenging to determine the viruses that are most similar to SARS‐CoV‐2. Even though the RaTG13 18 from the Rhinolophus affinis bat in Yunnan has the highest average genetic similarity to SARS‐CoV‐2, the historical background of recombination assumes that three other bat viruses, RmYN02, RpYN06, and PrC31, have relatively close viral RNA genome with that of SARS‐CoV‐2 (particularly ORF1ab). 52 , 53 Cross‐species transmission is commonly overlooked during its early phases. It is yet to be identified whether several other human coronaviruses like HCoV‐HKU1 and HCoV‐NL63 have animal origins or not. Despite the genetic similarity of bat coronaviruses to SARS‐CoV is more than 95%, their ability to use hACE‐2 as a receptor might have taken decades to naturally evolve. 54

The possibility of direct transmission of bat‐borne coronaviruses to humans seems to be a potential mode of spread. In 2012, many mineworkers were sent to clean bat feces from an abandoned mineshaft in Mojiang. This defunct copper mine in Mojiang, more than a thousand miles from Wuhan, is infested with horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus sinicus), which are the documented hosts of SARS‐like coronaviruses. Six of these miners contracted a mysterious illness and showed symptoms of severe pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Three of them died with symptoms suspected to be consistent with those of SARS‐like disease. All patients exhibited respiratory failure showing interstitial lung disease and alveolar lesions. Details about the deaths and symptoms of these miners were uncovered by a skeptic of the wet‐market hypothesis in the form of a Chinese master's thesis. 55 This episode is also referred to as the “first episode of the bat coronavirus outbreak” after the 2002 SARS outbreak. Therefore, it might be postulated that as the miners were previously working in an environment swarmed with bat feces, and all of the six patients had similar case histories, these circumstances must have some correlations with the development of SARS‐like diseases with pneumonia‐like symptoms or severe breathing‐associated symptoms arising from bat feces. A similar scenario could have happened just before SARS‐CoV‐2.

Transmission to humans through an intermediate host

The origin of SARS‐CoV‐2 was investigated to identify other animal viruses with a high degree of resemblance. As a result, new coronavirus genomes that may be involved in the potential zoonotic ecological niche (those circulating in chiropterans and in animals that come into contact with humans) are being sequenced. Pigs, goats, sheep, cows, and cats are examples of mammalian species whose ACE2 receptors are more similar to the main properties of the human receptor than those of the chiropterans. 56 Construction of pangolin farms and intense breeding of minks and raccoon dogs have become increasingly popular in China, bringing more health concerns in addition to concerns associated with practicality of such domestication. 57 Furthermore, these new alien farms coexist with intense domestic animal husbandry (such as poultry and pigs), which may facilitate the development of virus reservoirs (such as influenza) in regions that are densely populated. 58 The dependability of the results is determined by the quality of genome sequences, genomic restorations, information quality, and integrity of annotations in sequence databases. 59

Viruses intimately correlated with SARS‐CoV‐2 have been found in bats and pangolins in Southeast Asia, including China, Thailand, Cambodia, and Japan, which have been causing viral infections in pangolins for more than 10 years. 49 Although viral communication was discovered between coronaviruses affecting Malayan pangolins (Manis javanica) and those affecting other hosts, it was previously thought that pangolin coronavirus had no direct association with SARS‐CoV‐2. Pangolin‐CoV‐2019, a pangolin isolate, only shared a 91.02% whole‐genome identity with SARS‐CoV‐2, but higher sequence homology in the spike glycoprotein (S protein, 97.5%) coding sequence than Bat‐CoV‐RaTG13. 60 As a result, the pangolin is thought to be a possible intermediate host for SARS‐CoV‐2. The RBD of the S protein in SARS‐CoV‐2 is thought to have evolved via the recombination between a virus similar or related to Bat‐CoVRaTG13 and a virus similar or related to Pangolin‐CoV‐2019. 61 The SARS‐CoV‐2 RBD's binding free energy with human‐ACE2 is significantly lower than that of SARS, which explains the infectious capacity of SARS‐CoV‐2. 62 Although the potential importance of the RBD discovered in pangolin CoV‐2 has already been established, the region of high resemblance between pangolin virus and SARS‐CoV‐2 is short, and the possibility of pangolin‐to‐human transmission could be very low. Moreover, even the pangolin viruses most closely related to SARS‐CoV‐2 (such as MP789), including its bat coronavirus relatives (notably RaTG13 and RmYN02), have a low identity rate with SARS‐CoV‐2, implying that closer relatives and possibly more recent intermediate hosts are still unknown. 63 Hence, an in‐depth statistical analysis of the genomic recombination across coronaviruses from various hosts, particularly between pangolin and bat coronaviruses, should be conducted to trace the origin of SARS‐CoV‐2 and uncover evolutionary patterns.

Millions of live wild animals, comprising high‐risk species such as civets and raccoon dogs, were sold at Wuhan marketplaces in 2019, including the Huanan marketplace. 64 SARS‐CoV‐2 was discovered in samples taken from the Huanan market, primarily in the western section, which sells wildlife and domestic animal products, as well as from the sewage areas. 65 Even though animal carcasses tested negative for SARS‐CoV‐2 retrospectively, they were not the typical live animal species usually sold in this type of market and did not include raccoon dogs and other animals that are susceptible to SARS‐CoV‐2. 64 The earliest split in the SARS‐CoV‐2 phylogeny identified two lineages, A and B, 45 which apparently spread simultaneously. Lineage B was observed in individuals exposed to other marketplaces as well as those with later cases in Wuhan and other parts of China, whereas lineage A was observed in individuals exposed to other marketplaces as well as those with later cases in Wuhan and other parts of China. 65 The lineage A refers to Wuhan/WH04/2020 (EPI_ISL_406801), sampled on January 5, 2020, that shared two nucleotides (positions 8782 in ORF1ab and 28144 in ORF8) with the closest known bat viruses (RaTG13 and RmYN02). Lineage B, referred to those strains that had different nucleotides present at those sites as observed in Wuhan‐Hu‐1 (GenBank accession no. MN908947) sampled on December 26, 2019. 45

These findings are consistent with the emergence of SARS‐CoV‐2, which is associated with one or more infected animals, as well as with spillovers from numerous infected or extremely susceptible animals transported into or between Wuhan marketplaces, primarily through consensual networks and sold for human consumption. 18 Similar to SARS‐CoV, which was reported to have high levels of transmission, seroprevalence, and genetic variability in animals in the Dongmen market in Shenzhen and the Xinyuan market in Guangzhou, the virus might have proliferated across several regions. 65

Chinese authorities have conducted a sero‐prevalence survey of SARS‐CoV‐2 among animals during the initial period of the pandemic; however, they did not find any seropositive animals. 52 Apart from these studies, only a few research investigations have been conducted on mammals in the Wuhan or Yunnan region, which suggests the presence of an intermediate host for SARS‐CoV‐2. 63 In the last 2 years after the pandemic began, no intermediate host has been reported or identified. By contrast, the intermediate host of SARS and MERS was identified within 6 months. Thus, it remains challenging to confirm the intermediate host 2 years after the outbreak of COVID‐19. Moreover, investigating the marketplace that is now considered the “first victim of COVID‐19 pandemic” may not be sufficient to determine the source of the current outbreak. All possible traces, such as raw animal products used for trading or animal corpses, have been destroyed as preventive measures to eliminate further spillover chances. 66 Thus, in all possibilities, humanity might never know the intermediate host that could transmit the virus to humans, leading to the outbreak.

More recently, SARS‐CoV‐2 B.1.1.52‐infected 19/131 white‐tailed deer as evidenced by the presence of neutralizing antibodies and the presence of viral RNA in one animal. This finding could be very helpful in finding potential intermediate hosts. Screening the SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific antibodies to SARS‐CoV‐2 in closely related animal species in wet markets in China is highly recommended. Such an investigation could help in assessing the possible intermediate animal hosts for SARS‐CoV‐2 that might spillback to humans. 67

Laboratory origin (L)

Seepage from a laboratory incident

The emergence and human transmission of SARS‐CoV is an example of a laboratory incident that resulted in single illnesses and temporary transmission chains. Apart from the Marburg virus, 68 all pathogens that have escaped the laboratory setting are easily identifiable viruses capable of human infection and have been linked to long‐term research in slightly elevated settings. An example of the globally acknowledged human epidemic or pandemic resulting from scientific activities is the 1977 A/H1N1 influenza pandemic, which was most likely caused by a large‐scale vaccination challenge trial. 69

In 2021, all the available literature suggested that the emergence of SARS‐CoV‐2 was not due to an accidental escape of a laboratory strain and most likely had a zoonotic origin. 4 The assumptions were based on the following observations:

-

i.

None of the epidemics were caused by a novel virus escaping from a laboratory; moreover, there is no proof that the WIV conducted any previous research on SARS‐CoV‐2 or that any ancestor virus existed before the COVID‐19 pandemic. Since viruses are neutralized during RNA extraction, viral genome sequencing performed without cell culture does not pose a risk of virus transmission, and this procedure was performed at the WIV. 70 After sequencing the viral samples, no incidences of laboratory escape were reported. Reported experimental breakouts have been linked to the benchmark cases' job and familial contacts, as well as points of origin. 71

-

ii.

After a thorough investigation and tracking of early instances of the COVID‐19 epidemic, none of the episodes have been linked to the staff working at the WIV laboratory; when tested for SARS‐CoV‐2 in March 2020. 72 Reports of illnesses caused by SARS‐CoV‐2 should be validated to confirm if they are caused by the virus during the period of heightened influenza transmission as well as other respiratory virus transmissions. 72

-

iii.

According to the reports of previous studies, the WIV has successfully isolated three SARS coronaviruses from bats (WIV1, WIV16, and Rs4874) and has a vast library of bat‐derived materials. 73 , 74 Notably, SARS‐CoV is more closely linked to all three viruses than SARS‐CoV‐2. However, the RaTG13 virus from the WIV has never been isolated or cultivated and only exists in the form of a nucleotide sequence derived from short sequencing reads. 72

-

iv.

Although no existing evidence shows that the FCS site is artificially inserted in the laboratory, insertion of the FCS and RBD was assumed to be induced by site‐directed mutagenesis. 75 However, such speculation was aborted by the fact that a deletion of FCS did occur by serial passage of SARS‐CoV‐2 viruses in Vero E6 cells. 76 , 77 , 78 As a result, these approaches are unlikely to produce SARS‐CoV‐2 progenitors with functional FCS.

-

v.

According to undocumented reports, other techniques, such as the discovery of potential reverse genetics systems, were not applied at the WIV to generate infectious SARS‐CoVs based on bat sequencing data. Hence, gain‐of‐function studies should ideally use a known SARS‐CoV genetic backbone or, at the very least, a virus that has been identified through sequencing. Previous scientific work at the WIV using recombinant coronaviruses employed a genomic framework (WIV1) unrelated to SARS‐CoV‐2, and did not have the genetic markers that would be expected from laboratory experiments. 79

-

vi.

There is no reasonable rationale for establishing novel genetic engineering approaches using an undocumented virus, considering that there is no evidence or mention of a similar virus‐like SARS‐CoV‐2 from WIV or any nearly related candidates other than RaTG13. Hence, it is not reasonable to say that SARS‐CoV‐2 was present in the laboratory before the pandemic in any laboratory escape scenario; however, there is no factual data to prove it, and no sequence retrieved that can be referred to as progenitor.

-

vii.

One example of a laboratory escape scenario is the accidental infection during the serial passage of SARS‐CoV‐like viruses in ordinary laboratory animals such as mice. By contrast, early SARS‐CoV‐2 isolates could not infect wild‐type mice. 80 Although animal models are useful for studying the course of infection in vivo and testing various vaccines, they typically lead to the development of moderate or atypical disease in hACE2 transgenic mice. 81 These findings contradict the fact that a certain virus is chosen for use in animal models due to its increased pathogenicity and transmissibility to infect susceptible rodents’ multiple times. SARS‐CoV‐2 has now been generated 82 and serially passed into mice, 83 although adaptation in mice requires specific mutations in the spike protein, such as N501Y. 84 N501Y has appeared convergently in several human SARS‐CoV‐2 variants of concern, most likely as a result of the selection for a higher ACE2‐binding affinity. 85 If SARS‐CoV‐2 was produced from attempts to adapt a SARS‐CoV to be used in animal models, it would have acquired mutations such as N501Y to allow efficient replication in that model, but there is no evidence to support that such mutations existed at the commencement of the outbreak. Given its poor pathogenicity in commonly employed laboratory animals and the lack of genomic markers compatible with rodent adaptation, SARS‐CoV‐2 is unlikely to have been acquired by laboratory employees during viral pathogenesis or GoF studies.

Obscure origin (O)

Frozen food theory

On February 9, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) and Chinese investigations hypothesized that SAR‐CoV‐2 might have been transmitted to individuals handling frozen foods. 86 However, this hypothesis has received several criticisms. SARS‐CoV‐2 was initially detected on a cutting board used to handle imported salmon in Beijing's Xinfadi agricultural produce wholesale market on June 12, 2020. Over the next 2 weeks, 256 individuals were infected with SARS‐CoV‐2, of whom 98.8% had a history of exposure to the Xinfadi market. 65 The genome sequencing of a SARS‐CoV‐2 virus detected in a sample obtained from the Xinfadi market revealed a European coronavirus strain, providing a strong indication that the re‐emergent COVID‐19 cases in Beijing may be due to imported sources rather than a local transmission. 65 At least, nine food contamination incidents have been recorded around the country since the beginning of July 2020, with SARS‐CoV‐2 being found on imported items, predominantly in packing materials. 87 Nonetheless, none of these have provided for any verifiable facts or presented a focused position on the subject to date. The WHO, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Food and Drug Administration in the United States, as well as other regional regulatory bodies, have advised that there is no current evidence showing that the SARS‐CoV‐2 that caused COVID‐19 can spread through foods and that no specific foods should be withdrawn.

Later, in 2022, Multiple Working Hypothesis (MWH) suggested that big natural disasters like earthquakes, hurricanes, typhoons, and so forth cause higher deaths in a short period on comparing to deaths caused by naturally occurring (origin) zoonotic viruses like SARS‐CoV‐2. 88 A natural origin zoonotic virus has a remote possibility (i.e., rare events and low risk) of causing deaths as compared to the origin of viruses through laboratory has a higher probability of inflicting more deaths. 88

3.4. Concerns that raised suspicions about the current SARS‐CoV‐2

The zoonotic jump of coronaviruses to humans occurs frequently especially when one encounters a situation against the normal concept of nature. The Asian meat markets are known for their exotic trades of poached animals for human consumption. These animals are not normally present in close contact with humans. Accordingly, their presence together in close contact with each other and to humans constitutes a great potential of virus spill‐over from such animals to humans. So, the wet market theory is a logical consequence for the possible emergence of the SARS‐CoV‐2. Meanwhile, many facts raised the suspicion of the world for other scenarios that might be responsible for the current pandemic.

3.4.1. Work on chimeric coronaviruses

Different chimerics of SARS coronaviruses were created in the Baric laboratory in the USA as reviewed in, 89 including bat‐SCoV genome with the SARS‐CoV receptor‐binding domain, 90 BtCoV HKU5 with the SARS‐CoV spike (S) glycoprotein, 91 and murine adapted SARS‐CoV with SHC014 spike bat coronavirus. 92 Efficient replication in both mice and human airway cultures was noted in the latter chimeric virus without the need of any adaptation. These findings highlight the possible risks from the construction of chimeric from betacoronavirus. 92 The basic premise of these studies was to anticipate and prepare for the next pandemic (before the COVID‐19 hit).

3.4.2. Concern about the exact time of viral emergence

The wet market cases have been consistently claimed to be the earliest cases of the outbreak, lending credence to the “wet‐market hypothesis.” Some speculations that hypothesized that SARS‐CoV‐2 could be present before December 2019, which were augmented by post hoc data following analysis, showed that it is likely that the SARS‐CoV‐2 probably introduced before December 2019. 43 Researchers discovered and recovered a deleted set of incomplete SARS‐CoV‐2 sequences from the early Wuhan pandemic. Several inferences can be drawn from the analysis. First, the Huanan Seafood Market sequences, which were the topic of a joint WHO‐China study, may not represent all SARS‐CoV‐2 cases in Wuhan around the initial phases of the outbreak. According to the lost files and accessible sequences from Wuhan‐infected patients hospitalized in Guangdong, early Wuhan sequences were more likely to carry the T29095C mutation and were less likely to carry T8782C/C28144T than the sequences indicated in the joint WHO‐China report. 65 Second, there are two credible options for SARS‐CoV‐2 progenitors based on the available evidence. ProCoV‐2 was described, 93 while the other was a sequence with three mutations (C8782T, T28144C, and C29095T) compared with that of the Wuhan‐Hu‐1 sequence. Importantly, both possible progenitors are three mutations closer to the coronavirus cousins of SARS‐bat CoV‐2 than that of the sequences of viruses isolated from the Huanan Seafood Market. The progenitors of all known SARS‐CoV‐2 sequences could still be downstream of the sequence that infected patient zero, based on the transmission dynamics of the earliest infections. 43 This report was also augmented by the evidence of circulation of SARS‐CoV‐2 in November 2019 in France, 94 which confirms that the virus emergence was before November 2019.

3.5. Possibilities of Omicron evolution

The majority of SARS‐CoV‐2 mutations are repetitive or harmful; however, a handful of them improve viral function. D614G, the first known mutation linked to increased transmissibility, was discovered in early 2020. Since then, the virus has mutated, resulting in new mutations and a plethora of varieties. They could modify infectivity, transmissibility, or immune escape depending on the genes impacted and the location of the mutations. Because of the protein's function in the initial virus–cell contact and because it is the most changeable region in the virus genome, mutations that induce differences in the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein have been among the most investigated to date.

The severity of the sickness caused by virus variants is determined by their origin, genetic profile (some common mutations in the lineage), and the severity of the disease they cause, which determines the level of worry. 95 New varieties can outcompete others in the population if they improve their fitness. The Alpha form spread faster than previous generations because it was more transmissible. Beta and Gamma versions have accumulated mutations that allow them to partially evade immune systems and reduce vaccination effectiveness. Later, the Delta variant, discovered in March 2021, proliferated and superseded the other variants, becoming the most worrying of all the emerging lineages. 96

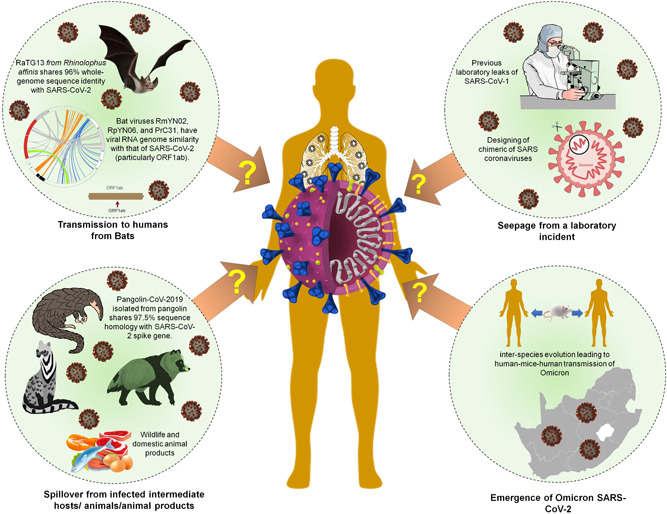

The Omicron type has now spread all over the world and is the most common. The SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron variant was first identified in South Africa on November 24, 2021, and was quickly designated as a variant of concern (VOC) by the World Health Organization (WHO) due to an increase in cases linked to this variant in South Africa (i.e., Omicron outbreak). Furthermore, the open reading frame encoding Omicron's spike protein (ORF S) has an unusually high number of mutations. The beginnings of Omicron's proximal origins have swiftly become a contentious matter of contention in the scientific and public health realms. 97 Many of the mutations found in Omicron were found in previously sequenced SARS‐CoV‐2 variants only infrequently, 96 , 98 leading to three popular interpretations about its evolutionary past. The first theory is that Omicron disseminated and circulated in a population with limited viral surveillance and sequencing. Second, Omicron could have evolved in a COVID‐19 patient who was chronically infected, such as an immunocompromised person, who provided a good host environment for long‐term intra‐host viral adaptation. The third scenario is that Omicron collected mutations in a nonhuman host before transferring to humans. 99 Omicron could have emerged by virus spillover to an animal host/reservoir such as jumping from humans to mice, gained mutations favorable to infect mice, and then reinfection to a human host would have occurred, reflecting an inter‐species evolution (human‐mice‐human) as proposed on the basis of the presence of mouse‐adapted mutation sites observed that might have facilitated adaptation of virus to mouse, 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 Therefore, “One Health” approaches have been suggested to be enhanced under the current scenario of Omicron variant outbreaks 103 , 104 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Theories of SARS‐CoV‐2 origin. SARS‐CoV‐2 shares sequence similarity with intermediate hosts including Bat‐CoV‐RaTG13, a bat coronavirus isolated from Rhinolophus affinis shares 96% whole‐genome sequence identity with SARS‐CoV‐2. SARS‐CoV‐2 has been shown to originate as a spillover from the infected intermediate hosts. Pangolin‐CoV‐2019, a pangolin isolates shared a higher sequence homology of 97.5% with spike glycoprotein. Similarly, SARS‐CoV‐2 might have spillover from infected live wild/domestic animals, including their products. Due to previous leakages of microorganisms from the laboratory, several theories support and contradict the origin of SARS‐CoV‐2 from laboratory leakage. Recent emergence of newer SARS‐CoV‐2 variants, Omicron is imposing serious concern about its origin which might be the result of inter‐species evolution of SARS‐CoV‐2.

4. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

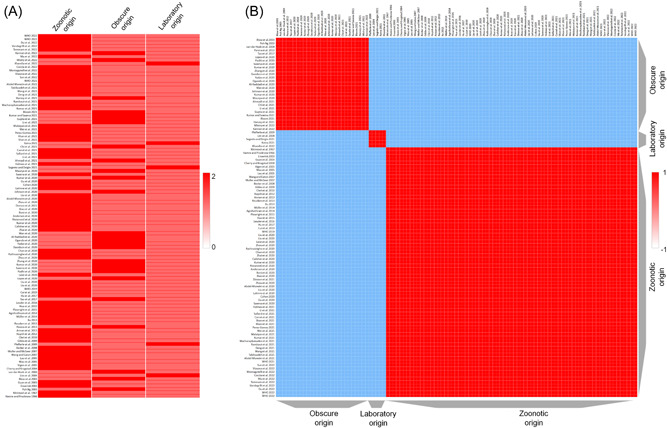

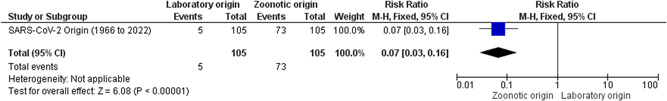

Based on our keyword searches in PubMed, CINAHL, and MEDLINE library databases, most of the authors favors the zoonotic spillover as the most probable origin of SARS‐CoV‐2 whereas origin based on laboratory spillover is unlikely as no concrete evidence is being shown to cite (Supporting Information: Table S1). (Supporting Information: Table S1 suggests that zoonotic origin (Z) have higher evidence‐based support as compared to laboratory origin (L). This has been represented by the heatmap supporting the zoonotic origin of SARS/SARS‐CoV‐2 (Figure 3A). Moreover, the row similarity matrix analysis further supports the zoonotic origin of SARS/SARS‐CoV‐2 (Figure 3B). Importantly, based on all the studies included, we generated the forest plot with 95% CIs of the risk ratio estimates. Our analysis showed that the black diamond supports the zoonotic origin of SARS/SARS‐CoV‐2 in the included studies (1966–2022; Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Heatmap and similarity matrix of SARS‐CoV‐2 origin. (A) Year‐wise studies (Supporting Information: Table S1) supporting the zoonotic origin (Z) of SARS‐CoV‐2 versus laboratory origin (L) versus obscure origin (O). The rows and columns have been hierarchically clustered using cosine‐distance and average linkage, where studies are clustered in rows. Red/blue cells in the matrix represent positive/negative values in the matrix. (B) Heatmap is showing the row similarity matrix among Z, L, and O. The cells in the matrix represent the similarity between rows, where red/blue represents a positive/negative similarity (measured as 1 − cosine‐distance).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of theories showing the hypothesis of SARS‐CoV‐2 origin. The horizontal line represents the risk ratio estimates at 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The black diamond supports the zoonotic origin (Z) of SARS‐CoV‐2 based on the included studies (Supporting Information: Table S1).

However, here in a thorough investigative and systematic approach, we have discussed all the possibilities related to the origin of SARS‐CoV‐2. Debunking misinformation and enhancing awareness about the necessity of research to determine the origin of pathogens are of utmost importance. The fact that the COVID‐19 pandemic occurred in the same region where the WIV is located, a state‐of‐the‐art virology laboratory that performs research on bat coronaviruses, fueled speculation that SARS‐CoV‐2 was developed in a laboratory. Notwithstanding the rhetoric, there seems to be no compelling proof that SARS‐CoV‐2 was ever reported to virologists before it emerged in December 2019, and all indicators imply that, like SARS and MERS, this virus most likely evolved in a bat host unless an unknown human spillover event occurred.

Nevertheless, this accomplished hardly anything to halt the proliferation of often paradoxical and, at times, completely absurd conspiracy theories that propagated more rapidly than the disease outbreak itself. For example, it has been claimed that SARS‐CoV‐2 was either the consequence of a laboratory error or was purposefully manufactured or it was produced for GoF investigations, which were previously undertaken with bat SARS‐like coronaviruses to investigate the cross‐species transmission risk. However, performing such research under global prying eyes seems unlikely. Furthermore, disease emergence due to a natural cause has a long history: most new viruses that have caused epidemics or pandemics in humans have originated organically from wildlife reservoirs. As a result, the overwhelming opinion is that this virus entered into a susceptible human host through contact with an infected animal, alternatively through contact with infectious animal tissues.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Shailendra K. Saxena conceived the idea and planned the study. Nagendra Thakur, Sayak Das, Swatantra Kumar, Vimal K Maurya, and Shailendra K. Saxena collected the data, devised the initial draft, reviewed the final draft, and contributed equally to this study as the first author. Shailendra K. Saxena, Nagendra Thakur, Sayak Das, Swatantra Kumar, Vimal K. Maurya, Kuldeep Dhama, Janusz T. Paweska, Ahmed S. Abdel‐Moneim, Amita Jain, Anil K. Tripathi, and Bipin Puri finalized the draft for submission. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Vice Chancellor, King George's Medical University (KGMU) Lucknow, for the encouragement for this work. Ahmed S. Abdel‐Moneim also acknowledges the support of Taif University Researchers Supporting Project No. TURSP‐2020/11. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Thakur N, Das S, Kumar S, et al. Tracing the origin of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2): a systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Med Virol. 2022;1‐14. 10.1002/jmv.28060

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Dashboard. Accessed February 28, 2022. https://covid19.who.int/

- 2. Harvey WT, Carabelli AM, Jackson B, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(7):409‐424. 10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Padhi A, Kumar S, Gupta E, Saxena SK. Laboratory diagnosis of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) infection. In: Saxena S. K., ed. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapeutics. Springer; 2020:95‐107. 10.1007/978-981-15-4814-7_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holmes EC, Goldstein SA, Rasmussen AL, et al. The origins of SARS‐CoV‐2: a critical review. Cell. 2021;184(19):4848‐4856. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fernandez NF, Gundersen GW, Rahman A, et al. Clustergrammer, a web‐based heatmap visualization and analysis tool for high‐dimensional biological data. Sci Data. 2017;4:170151. 10.1038/sdata.2017.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hamre D, Procknow JJ. A new virus isolated from the human respiratory tract. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1966;121(1):190‐193. 10.3181/00379727-121-30734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McIntosh K, Dees JH, Becker WB, Kapikian AZ, Chanock RM. Recovery in tracheal organ cultures of novel viruses from patients with respiratory disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;57(4):933‐940. 10.1073/pnas.57.4.933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vijgen L, Keyaerts E, Moës E, et al. Complete genomic sequence of human coronavirus OC43: molecular clock analysis suggests a relatively recent zoonotic coronavirus transmission event. J Virol. 2005;79(3):1595‐1604. 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1595-1604.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Hoek L, Pyrc K, Jebbink MF, et al. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat Med. 2004;10(4):368‐373. 10.1038/nm1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cherry JD, Krogstad P. SARS: the first pandemic of the 21st century. Pediatr Res. 2004;56(1):1‐5. 10.1203/01.PDR.0000129184.87042.FC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Woo PC, Lau SK, Chu CM, et al. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J Virol. 2005;79(2):884‐895. 10.1128/JVI.79.2.884-895.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chan JF, Kok KH, Zhu Z, et al. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human‐pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan [published correction appears in Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):540]. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):221‐236. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1719902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cleri DJ, Ricketti AJ, Vernaleo JR. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24(1):175‐202. 10.1016/j.idc.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Müller MA, Corman VM, Jores J, et al. MERS coronavirus neutralizing antibodies in camels, Eastern Africa, 1983‐1997. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(12):2093‐2095. 10.3201/eid2012.141026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization . Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV). 2019. Accessed February 26, 2022. http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/

- 16. Lessler J, Salje H, Van Kerkhove MD, et al. Estimating the severity and subclinical burden of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(7):657‐663. 10.1093/aje/kwv452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Al‐Raddadi RM, Shabouni OI, Alraddadi ZM, et al. Burden of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(5):692‐696. 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270‐273. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou H, Chen X, Hu T, et al. A novel bat Coronavirus closely related to SARS‐CoV‐2 contains natural insertions at the S1/S2 cleavage site of the spike protein. Curr Biol. 2020;30(19):3896. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abdel‐Moneim AS, Abdelwhab EM. Evidence for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection of animal hosts. Pathogens. 2020;9(7):529. 10.3390/pathogens9070529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Annan A, Baldwin HJ, Corman VM, et al. Human betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012‐related viruses in bats, Ghana and Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(3):456‐459. 10.3201/eid1903.121503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181‐192. 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huynh J, Li S, Yount B, et al. Evidence supporting a zoonotic origin of human coronavirus strain NL63. J Virol. 2012;86(23):12816‐12825. 10.1128/JVI.00906-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lau SKP, Woo PCY, Li KSM, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc Natl AcadSci USA. 2005;102(39):14040‐14045. 10.1073/pnas.0506735102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pfefferle S, Oppong S, Drexler JF, et al. Distant relatives of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and close relatives of human coronavirus 229E in bats, Ghana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(9):1377‐1384. 10.3201/eid1509.090224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perera RA, Wang P, Gomaa MR, et al. Seroepidemiology for MERS coronavirus using microneutralisation and pseudoparticle virus neutralisation assays reveal a high prevalence of antibody in dromedary camels in Egypt, June 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(36):pii=20574. 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.36.20574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reusken CB, Haagmans BL, Müller MA, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(10):859‐866. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tao Y, Shi M, Chommanard C, et al. Surveillance of bat coronaviruses in Kenya identifies relatives of human coronaviruses NL63 and 229E and their recombination history. J Virol. 2017;91(5):e01953‐16. 10.1128/JVI.01953-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guan Y, Zheng BJ, He YQ, et al. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003;302(5643):276‐278. 10.1126/science.1087139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang LF, Eaton BTBats. Civets and the emergence of SARS. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;315:325‐344. 10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Boni MF, Lemey P, Jiang X, et al. Evolutionary origins of the SARS‐CoV‐2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID‐19 pandemic. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(11):1408‐1417. 10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saxena SK, Kumar S, Maurya VK, Sharma R, Dandu HR, Bhatt M. Current insight into the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). In: Saxena SK, ed. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapeutics. Springer; 2020:1‐8. 10.1007/978-981-15-4814-7_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Acute respiratory syndrome . China, Hong Kong special administrative region of China, and Viet Nam. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2003;78(11):73‐74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Muller MP, McGeer A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus. SeminRespirCrit Care Med. 2007;28(2):201‐212. 10.1055/s-2007-976492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Poh Ng LF. The virus that changed my world. PLoS Biol. 2003;1(3):E66. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kumar S, Nyodu R, Maurya VK, Saxena SK. Morphology, genome organization, replication, and pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). In: Saxena SK, ed. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapeutics. Springer; 2020:23‐31. 10.1007/978-981-15-4814-7_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yadav T, Srivastava N, Mishra G, et al. Recombinant vaccines for COVID‐19. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(12):2905‐2912. 10.1080/21645515.2020.1820808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kumar S, Maurya VK, Prasad AK, Bhatt MLB, Saxena SK. Structural, glycosylation and antigenic variation between 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) and SARS coronavirus (SARS‐CoV. Virus Dis. 2020;31(1):13‐21. 10.1007/s13337-020-00571-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kumar S, Nyodu R, Maurya VK, Saxena SK. Host immune response and immunobiology of human SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. In: Saxena SK, ed. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Medical Virology: From Pathogenesis to Disease Control. Springer; 2020. 10.1007/978-981-15-4814-7_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gupta A, Pradhan A, Maurya VK, et al. Therapeutic approaches for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Methods. 2021;195:29‐43. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2021.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Malaiyan J, Arumugam S, Mohan K, GomathiRadhakrishnan G. An update on the origin of SARS‐CoV‐2: despite closest identity, bat (RaTG13) and pangolin derived coronaviruses varied in the critical binding site and O‐linked glycan residues. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):499‐505. 10.1002/jmv.26261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Johnson BA, Xie X, Kalveram B, et al. Furin cleavage site is key to SARS‐CoV‐2 pathogenesis. Preprint. bioRxiv. 2020;2020.08.26.268854. 10.1101/2020.08.26.268854 [DOI]

- 43. Bloom JD. Recovery of deleted deep sequencing data sheds more light on the early Wuhan SARS‐CoV‐2 epidemic. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(12):5211‐5224. 10.1093/molbev/msab246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaina B. On the origin of SARS‐CoV‐2: did cell culture experiments lead to increased virulence of the progenitor virus for humans? In Vivo. 2021;35(3):1313‐1326. 10.21873/invivo.12384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rambaut A, Holmes EC, O'Toole Á, et al. Addendum: A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS‐CoV‐2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6(3):415. 10.1038/s41564-021-00872-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tabibzadeh A, Esghaei M, Soltani S, et al. Evolutionary study of COVID‐19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) as an emerging coronavirus: phylogenetic analysis and literature review. Vet Med Sci. 2021;7(2):559‐571. 10.1002/vms3.394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ahmadi K, Zahedifard F, Mafakher L, et al. Active site‐based analysis of structural proteins for drug targets in different human Coronaviruses. ChemBiol Drug Des. 2021;99:585‐602. 10.1111/cbdd.14004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Temmam S, Vongphayloth K, Baquero E, et al. Bat coronaviruses related to SARS‐CoV‐2 and infectious for human cells. Nature. 2022;604:330‐336. 10.1038/s41586-022-04532-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wacharapluesadee S, Tan CW, Maneeorn P, et al. Evidence for SARS‐CoV‐2 related coronaviruses circulating in bats and pangolins in Southeast Asia 2021;12(1):1430]. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):972. Published 2021 Feb 9. 10.1038/s41467-021-21240-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Deng S, Xing K, He X. Mutation signatures inform the natural host of SARS‐CoV‐2. Natl Sci Rev. 2021;9(2):nwab220. 10.1093/nsr/nwab220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shan KJ, Wei C, Wang Y, Huan Q, Qian W. Host‐specific asymmetric accumulation of mutation types reveals that the origin of SARS‐CoV‐2 is consistent with a natural process. Innovation. 2021;2(4):100159. 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li Z, Guan X, Mao N, et al. Antibody seroprevalence in the epicenter Wuhan, Hubei, and six selected provinces after containment of the first epidemic wave of COVID‐19 in China. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2021;8:100094. 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li L, Wang J, Ma X, et al. A novel SARS‐CoV‐2 related coronavirus with complex recombination isolated from bats in Yunnan province, China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10(1):1683‐1690. 10.1080/22221751.2021.1964925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hu B, Zeng LP, Yang XL, et al. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS‐related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(11):e1006698. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu L. The Analysis of Six Patients with Severe Pneumonia Caused by Unknown Viruses. Master's Thesis, School of Clinical Medicine, Kun Ming Medical University; 2013.

- 56. Zhai X, Sun J, Yan Z, et al. Comparison of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike protein binding to ACE2 receptors from human, pets, farm animals, and putative intermediate hosts. J Virol. 2020;94(15):e00831‐20. 10.1128/JVI.00831-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hua L, Gong S, Wang F, et al. Captive breeding of pangolins: current status, problems and future prospects. Zookeys. 2015;507(507):99‐114. 10.3897/zookeys.507.6970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gibbs AJ, Armstrong JS, Downie JC. From where did the 2009 ‘swine‐origin’ influenza A virus (H1N1) emerge? Virol J. 2009;6:207. 10.1186/1743-422X-6-207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sallard E, Halloy J, Casane D, Decroly E, van Helden J. Tracing the origins of SARS‐COV‐2 in coronavirus phylogenies: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:1‐17. 10.1007/s10311-020-01151-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lopes LR, de MattosCardillo G, Paiva PB. Molecular evolution and phylogenetic analysis of SARS‐CoV‐2 and hosts ACE2 protein suggest Malayan pangolin as intermediary host. Braz J Microbiol. 2020;51(4):1593‐1599. 10.1007/s42770-020-00321-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Xiao K, Zhai J, Feng Y, et al. Isolation of SARS‐CoV‐2‐related coronavirus from Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020;583(7815):286‐289. 10.1038/s41586-020-2313-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang T, Wu Q, Zhang Z. Probable Pangolin origin of SARS‐CoV‐2 associated with the COVID‐19 outbreak. Curr Biol. 2020;30(7):1346‐1351.e2. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Liu P, Jiang JZ, Wan XF, et al. Are pangolins the intermediate host of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2). PLoSPathog. 2020;16(5):e1008421. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Xiao X, Newman C, Buesching CD, Macdonald DW, Zhou ZM Animal sales from Wuhan wet markets immediately prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):11898. 10.1038/s41598-021-91470-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. World Health Organization (WHO) WHO‐convened global study of origins of SARS‐CoV‐2: China Part. 2021. Accessed February 26, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/whoconvened-global-study-of-origins-of-sars-cov-2-china-part

- 66. Plowright RK, Eby P, Hudson PJ, et al. Ecological dynamics of emerging bat virus spillover. Proc Biol Sci. 2015;282(1798):20142124. 10.1098/rspb.2014.2124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vandegrift KJ, Yon M, Surendran‐Nair M, et alDetection of SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) infection of white‐tailed deer. Preprint. bioRxiv. 2022;2022.02.04.479189. 10.1101/2022.02.04.479189 [DOI]

- 68. Ristanović ES, Kokoškov NS, Crozier I, Kuhn JH, Gligić AS. A forgotten episode of marburg virus disease: Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1967. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2020;84(2):e00095‐19. 10.1128/MMBR.00095-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rozo M, Gronvall GK. The Reemergent 1977 H1N1 Strain and the Gain‐of‐Function Debate. mBio. 2015;6(4):e01013‐15. 10.1128/mBio.01013-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Blow JA, Dohm DJ, Negley DL, Mores CN. Virus inactivation by nucleic acid extraction reagents. J Virol Methods. 2004;119(2):195‐198. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lim PL, Kurup A, Gopalakrishna G, et al. Laboratory‐acquired severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(17):1740‐1745. 10.1056/NEJMoa032565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Cohen J. Wuhan coronavirus hunter Shi Zhengli speaks out. Science. 2020;369(6503):487‐488. 10.1126/science.369.6503.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Liu M, Deng L, Wang D, Jiang T. Influenza activity during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 in Chinese mainland. Biosaf Health. 2020;2(4):206‐209. 10.1016/j.bsheal.2020.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Latinne A, Hu B, Olival KJ, et al. Origin and cross‐species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China. Preprint. bioRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.05.31.116061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 75. Segreto R, Deigin Y. The genetic structure of SARS‐CoV‐2 does not rule out a laboratory origin: SARS‐COV‐2 chimeric structure and furin cleavage site might be the result of genetic manipulation. BioEssays. 2021;43(3):e2000240. 10.1002/bies.202000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Davidson AD, Williamson MK, Lewis S, et al. Characterisation of the transcriptome and proteome of SARS‐CoV‐2 reveals a cell passage induced in‐frame deletion of the furin‐like cleavage site from the spike glycoprotein. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):68. 10.1186/s13073-020-00763-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kumar S, Saxena SK. Structural and molecular perspectives of SARS‐CoV‐2. Methods. 2021;195:23‐28. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2021.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ogando NS, Dalebout TJ, Zevenhoven‐Dobbe JC, et al. SARS‐coronavirus‐2 replication in vero E6 cells: replication kinetics, rapid adaptation and cytopathology. J Gen Virol. 2020;101(9):925‐940. 10.1099/jgv.0.001453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF. The proximal origin of SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):450‐452. 10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from wuhan: an analysis based on decade‐long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94(7):e00127‐20. 10.1128/JVI.00127-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rathnasinghe R, Strohmeier S, Amanat F, et al. Comparison of transgenic and adenovirus hACE2 mouse models for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):2433‐2445. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1838955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Dinnon KH, 3rd , Leist SR, Schäfer A, et al. A mouse‐adapted model of SARS‐CoV‐2 to test COVID‐19 countermeasures [published correction appears in Nature. 2021;590(7844):E22]. Nature. 2020;586(7830):560‐566. 10.1038/s41586-020-2708-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Leist SR, Dinnon KH, 3rd , Schäfer A, et al. A mouse‐adapted SARS‐CoV‐2 induces acute lung injury and mortality in standard laboratory mice. Cell. 2020;183(4):1070‐1085.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Gu H, Chen Q, Yang G, et al. Adaptation of SARS‐CoV‐2 in BALB/c mice for testing vaccine efficacy. Science. 2020;369(6511):1603‐1607. 10.1126/science.abc4730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Khan A, Zia T, Suleman M, et al. Higher infectivity of the SARS‐CoV‐2 new variants is associated with K417N/T, E484K, and N501Y mutants: an insight from structural data. J Cell Physiol. 2021;236(10):7045‐7057. 10.1002/jcp.30367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Liu P, Yang M, Zhao X, et al. Cold‐chain transportation in the frozen food industry may have caused a recurrence of COVID‐19 cases in destination: successful isolation of SARS‐CoV‐2 virus from the imported frozen cod package surface. BiosafHealth. 2020;2(4):199‐201. 10.1016/j.bsheal.2020.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Chi Y, Wang Q, Chen G, Zheng S. The long‐term presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 on cold‐chain food packaging surfaces indicates a new COVID‐19 winter outbreak: a mini review. Front Public Health. 2021;9:650493. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.650493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Coccia M. Meta‐analysis to explain unknown cases of the origins of SARS‐COV‐2. Environ Res. 2022;211:113062. 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Abdel‐Moneim AS, Abdelwhab EM, Memish ZA. Insights into SARS‐CoV‐2 evolution, potential antivirals, and vaccines. Virology.2021. 2021;558:1‐12. 10.1016/j.virol.2021.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Becker MM, Graham RL, Donaldson EF, et al. Synthetic recombinant bat SARS‐like coronavirus is infectious in cultured cells and in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(50):19944‐19949. 10.1073/pnas.0808116105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Agnihothram S, Yount BL Jr., Donaldson EF, et al. A mouse model for Betacoronavirus subgroup 2c using a bat coronavirus strain HKU5 variant. mBio. 2014;5(2):e00047‐e14. 10.1128/mBio.00047-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Menachery VD, Yount BL Jr, Debbink K, et al. Author Correction: a SARS‐like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1146. 10.1038/s41591-020-0924-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kumar S, Tao Q, Weaver S, et al. An evolutionary portrait of the progenitor SARS‐CoV‐2 and its dominant offshoots in COVID‐19 pandemic. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(8):3046‐3059. 10.1093/molbev/msab118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Carrat F, Figoni J, Henny J, et al. Evidence of early circulation of SARS‐CoV‐2 in France: findings from the population‐based “CONSTANCES” cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36(2):219‐222. 10.1007/s10654-020-00716-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Perez‐Gomez R. The development of SARS‐CoV‐2 variants: the gene makes the disease. J Dev Biol. 2021;9(4):58. 10.3390/jdb9040058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Mistry P, Barmania F, Mellet J, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 variants, vaccines, and host immunity. Front Immunol. 2022;12:809244. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.809244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Sun Y, Lin W, Dong W, Xu J. Origin and evolutionary analysis of the SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron variant. J Biosaf Biosecur. 2022;4(1):33‐37. 10.1016/j.jobb.2021.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ma W, Yang J, Fu H, et al. Genomic perspectives on the emerging SARS‐CoV‐2 omicron variant. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2022:S1672‐0229. 10.1016/j.gpb.2022.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99. Wei C, Shan KJ, Wang W, Zhang S, Huan Q, Qian W. Evidence for a mouse origin of the SARS‐CoV‐2 omicron variant. J Genet Genomics. 2021;48(12):1111‐1121. 10.1016/j.jgg.2021.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Du P, Gao GF, Wang Q. The mysterious origins of the Omicron variant of SARS‐CoV‐2. Innovation. 2022;3(2):100206. 10.1016/j.xinn.2022.100206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kannan SR, Spratt AN, Sharma K, Chand HS, Byrareddy SN, Singh K. Omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 variant: unique features and their impact on pre‐existing antibodies. J Autoimmun. 2022;126:102779. 10.1016/j.jaut.2021.102779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Saxena SK, Kumar S, Ansari S, et al. Characterization of the novel SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant of concern and its global perspective. J Med Virol. 2022. Apr;94(4):1738‐1744. 10.1002/jmv.27524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Khandia R, Singhal S, Alqahtani T, et al. Emergence of SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant, salient features, high global health concerns and strategies to counter it amid ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic. Environ Res. 2022;209:112816. 10.1016/j.envres.2022.112816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Montagutelli X, van der Werf S, Rey FA, Simon‐Loriere E. SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron emergence urges for reinforced One‐Health surveillance. EMBO Mol Med. 2022;14(3):e15558. 10.15252/emmm.202115558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.