Abstract

Background

We aimed to analyze the humoral and cellular response to standard and booster (additional doses) COVID‐19 vaccination in solid organ transplantation (SOT) and the risk factors involved for an impaired response.

Methods

We did a systematic review and meta‐analysis of studies published up until January 11, 2022, that reported immunogenicity of COVID‐19 vaccine among SOT. The study is registered with PROSPERO, number CRD42022300547.

Results

Of the 1527 studies, 112 studies, which involved 15391 SOT and 2844 healthy controls, were included. SOT showed a low humoral response (effect size [ES]: 0.44 [0.40–0.48]) in overall and in control studies (log‐Odds‐ratio [OR]: −4.46 [−8.10 to −2.35]). The humoral response was highest in liver (ES: 0.67 [0.61–0.74]) followed by heart (ES: 0.45 [0.32–0.59]), kidney (ES: 0.40 [0.36–0.45]), kidney‐pancreas (ES: 0.33 [0.13–0.53]), and lung (0.27 [0.17–0.37]). The meta‐analysis for standard and booster dose (ES: 0.43 [0.39–0.47] vs. 0.51 [0.43–0.54]) showed a marginal increase of 18% efficacy. SOT with prior infection had higher response (ES: 0.94 [0.92–0.96] vs. ES: 0.40 [0.39–0.41]; p‐value < .01). The seroresponse with mRNA‐12723 mRNA was highest 0.52 (0.40–0.64). Mycophenolic acid (OR: 1.42 [1.21–1.63]) and Belatacept (OR: 1.89 [1.3–2.49]) had highest risk for nonresponse. SOT had a parallelly decreased cellular response (ES: 0.42 [0.32–0.52]) in overall and control studies (OR: −3.12 [−0.4.12 to −2.13]).

Interpretation

Overall, SOT develops a suboptimal response compared to the general population. Immunosuppression including mycophenolic acid, belatacept, and tacrolimus is associated with decreased response. Booster doses increase the immune response, but further upgradation in vaccination strategy for SOT is required.

Keywords: additional dose immunogenicity, booster, SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine, solid organ transplantation

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- CNI

calineurin inhibitor

- eGFR

glomerular filtration rate

- ES

effect size

- IQR

interquartile range

- MMF

mycophenolic acid

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NOS

Newcastle‐Ottawa scale

- OR

log‐odds ratio

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- SOT

solid organ transplantation

1. INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2) vaccine is the prime arsenal for battling the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic because of the failure of definitive therapy. 1 Solid organ transplantation (SOT) population is among the most vulnerable groups for high morbidity and mortality in the pandemic. 2 , 3 To add to the burden, the vaccine response in SOT has not been encouraging. So far, all the large‐scale randomized controlled trials 4 , 5 for various COVID‐19 vaccines have excluded SOT. Hence, high‐level evidence‐based in this context is unavailable. With reports of higher breakthrough COVID‐19 cases in SOT, 6 , 7 a timely and in‐depth analysis of vaccine responsiveness becomes imperative. We hereby address this knowledge gap in this systematic review and metanalysis to address the immunogenicity (both cellular and humoral) of different COVID‐19 vaccines among SOT. We also interrogated the risk factors for decreased responsiveness and measured the impact of booster dosing in SOT.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Literature search strategy and eligibility criteria

This systematic review and meta‐analysis was conducted and reported in accordance with the meta‐analyses of observational studies in epidemiology checklist. 8 The study is registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42022300547 on January 6, 2022), which is a validated and recognized database for meta‐analysis. We have utilized search engines of PubMed, Google scholar, Medline, and World Health Organization (WHO) COVID‐19 research portal with the data published between January 1, 2020 and January 11, 2022 (Table S1). The search included only studies in the English language. There were no other limits or filters. The primary search terms used were COVID, vaccine, transplant. The other search strings used in the search engine included SOT, kidney, lung, pancreas, lung, SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine, COVID‐19 vaccine, ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19, Oxford–AstraZeneca, mRNA vaccines, BNT162b2, and mRNA‐1273. We have not included the outcomes studied like immune response, antibody response, seroconversion, or immunogenicity as the MeSH term, to broaden the data retrieved and to avoid any missing report. Preprint materials were not included in this study. Other grey literature published as abstracts in journals and WHO portal for COVID‐19 research were also excluded.

The inclusion criteria included studies with the population who had a history of any SOT and studied immunogenicity response (antibody and/or cellular) following a complete schedule of vaccination. The absence of a control group was not a criterion for exclusion. Exclusion criteria were the studies reporting reactogenicity only and studies with a single‐dose immune response. The type of articles included was clinical trials, letters, and original articles with cases more than two. Systemic reviews, personal viewpoints, and editorials were excluded. The manual search was performed by two independent reviewers (S.C. and V.B.K.) to reduce bias and to retrieve data from drop‐outs of the first search. The manual search was performed by both forward and backward snowballing methods. Two independent reviewers (H.R. and R.D.) independently assessed the validity of the titles, abstracts, and full texts of each publication.

2.2. Outcome ascertainment and data extraction

The primary outcome was the immunogenicity response (humoral or cellular response measured separately) to the COVID‐19 vaccine following complete vaccination among SOT. The antibody response was reported in the following sequence: antispike protein IgG, antireceptor‐binding domain protein, or neutralization antibodies. Cellular response rates were analyzed for the available studies. The immunogenicity response was recorded as a binary outcome, and continuous outcomes were not studied, due to wide variability in cut‐off titers for different tests performed. Thus, for seroresponse, we have recorded studies reporting a yes or no response, and the same procedure was applied for cell‐mediated immunity. And also, we have not assessed quantitative values reported in the studies for humoral or cellular immunity. Two reviewers (H.S.M. and V.B.K.) were involved in the data extraction independently. We also extracted relevant variables, including the patient's age, sex, timing from transplantation to vaccination, type of vaccine, number of doses, time of testing from the last dose, history of prior COVID‐19, immunosuppression regimen, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) for assessing the risk factors for decreased immune response. We have excluded these variables from our analysis if the reporting is given in univariate or multivariate odds ratios. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus with a third author (S.C). The missing data were not traced to the concerned study investigators for additional information, as the data for primary outcomes of interest were reported in all the included studies. The other outcome was the immunogenicity rates of SOT compared with healthy controls.

2.3. Quality of study assessment

The quality of the non‐randomized controlled trial studies was assessed by two independent reviewers (V.B.K and H.R.) using the Newcastle‐Ottawa scale (NOS), which is a widely accepted method of assessing the quality of evidence for observational studies. 9 This tool has a maximum of nine points in three major categories: quality of the selection, comparability, and the outcome of study participants. Studies that reported scores between 7 and 9 points were indicated as having low risk; 4 and 6 points as a moderate risk; and <4 points as high risk for bias. Any conflict in the quality check for a study was resolved from discussion with the third reviewer (RD) and finalized thence. We have not excluded any study based on the lower points in NOS detected.

2.4. Statistical procedure

Data analysis for the meta‐analysis was performed by H.S.M. through statistical software of STATA 16 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). Double data checking was performed by the co‐investigator (S.C.) before analysis. Categorical outcome was reported as frequencies, and percentages while continuous outcomes were reported as median, mean, standard deviation, interquartile range (IQR), and range as per the availability. To combine two means and standard deviation, decomposition was done and reported by Cochrane's formula. 10 Standard deviation was calculated by dividing IQR by 1.35 and range by 4. To perform meta‐analyses of binomial data with no control group, metaprop commands, which is an extension of STATA, was used which allows computation of 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the score statistic and the exact binomial method. To perform a meta‐analysis of binary data with two groups (SOT and control) and continuous outcomes (eGFR and tacrolimus levels), we used the DerSimonian‐Laird random effect model as the statistical method. The outcomes were reported as effect size, log odds ratio, and Hegde's g with an accompanying 95% CI. I 2 statistic was used to assess the heterogeneity of the pooled estimate, where a value above 0.5 indicated substantial heterogeneity. For exploring the potential source of heterogeneity in cellular response, we conducted several subgroup analyses for (1) standard or booster vaccination; (2) different vaccine responses. We computed separate effect sizes for humoral response in SOT for (1) organ wise immunogenicity response (2) prior or naïve SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (3) different vaccine response (4) standard or booster vaccination. We reported the effect sizes of pooled data for the aforementioned subgroups. We have also performed univariate random‐effects meta‐regression analysis with the use of the following study‐level explanatory variables: median age, the number of males, and years of transplantation from vaccination. The rationale for selecting these continuous data variables is their attenuating effect on immune response with COVID‐19 vaccine in majority of the studies. Data visualization for the outcomes was completed by forest plots and bubble plots. In the forest plots, the columns are added to show the exact number of cases with a response or no response. Publication bias was described with funnel plots and egger's test. Sensitivity analysis was done for humoral response studies by excluding small sample studies (defined as having cases less than 100 for this purpose). Sensitivity analysis for cellular response studies was done with studies including a sample size of 50 or more. A p‐value of less than .05 was used as a measure of statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

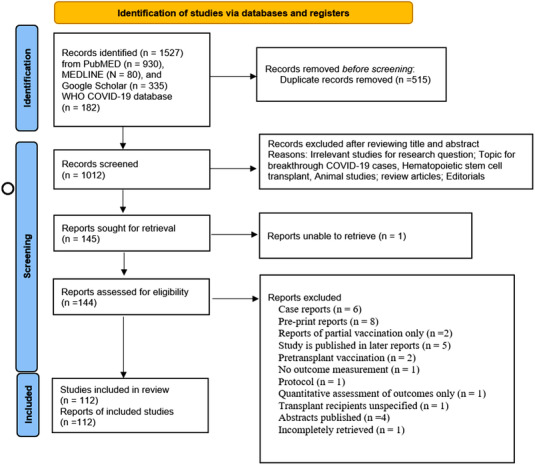

We identified 903 potentially eligible studies from PubMed, 80 potentially eligible studies from MEDLINE, 335 potentially eligible studies from Google scholar database, and 182 studies from WHO COVID‐19 research database. The detailed search results are shown in Figure 1. The grey literature including preprint studies and conference abstracts were identified and excluded. After removing duplicate articles, a total of 1012 studies were screened. After the exclusion of irrelevant studies, including studies not addressing the outcome of interest and studies only reporting breakthrough cases, reactogenicity, and single dose‐response, 112 studies were included in the meta‐analysis. A total of 33 reports were excluded in the process. The details of excluded studies with explanatory reasons are summarized in Table S2.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for the study. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma‐statement.org/

Table S3 shows the baseline characteristics of the studies 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 included. For this meta‐analysis, a total of 112 studies were finally included, which involved 15391 SOT and 2844 healthy controls. The bulk of the studies originated from European followed by American regions, while only three reports were published from the South‐East Asian region. The median (IQR) age of the patients was 59 (55–62) years. There was a disproportionate sex distribution with 8949 (58.1%) males in the study. Table S4 depicts the vaccination strategies and outcomes of the studies. The vaccines reported were BNT162b2, mRNA‐1723, ChAdOx1nCoV‐19, and inactivated whole virus vaccine. Nineteen studies 17 , 21 , 29 , 30 , 42 , 56 , 59 , 68 , 70 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 86 , 90 , 97 , 107 , 113 , 119 , 120 have reported and discussed immunogenicity after a booster dose. The testing methods mostly involved anti‐spike protein IgG and interferon‐gamma release assay for T‐cell response against SARS‐CoV‐2. There was a variation in the timing of response testing after the last dose.

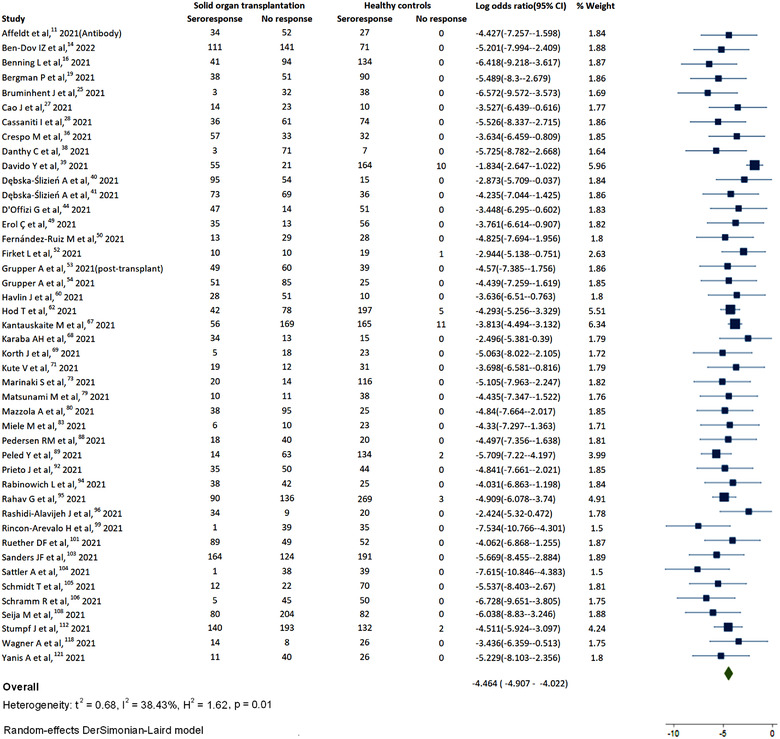

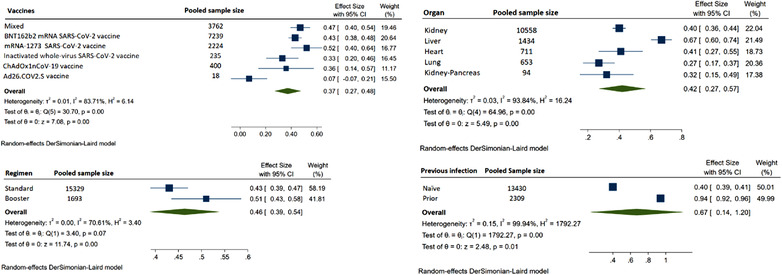

Figure 2 shows the forest plot of humoral response with COVID‐19 vaccine in SOT compared to healthy controls. SOT (log odds‐ratio: −4.46 [−8.10 to −2.35]; I 2 = 38.43%) had lower chances of showing antibody response compared to controls, and also there was mild heterogeneity for the results. The forest plot of humoral response from all the studies is depicted in Figure S1, which yielded low pooled immunogenicity (ES: 0.44 [0.40–0.48]; I 2 = 95.92%). The forest plots for humoral response for individual organs are depicted in Figures S2–S4. Figure 3 shows the metanalysis assessing humoral response from pooled sample sizes. From 13450 organ transplant patients (kidney: 10588; liver: 1434; heart: 711; lung: 653 and pancreas: 94), the highest humoral response rate was reported for liver (ES: 0.67 [0.61–0.74]; I 2 = 97.42%) followed by heart (ES: 0.45 [0.32–0.59]; I 2 = 93.92%), kidney (ES: 0.40 [0.36–0.45]; I 2 = 95.7%), kidney‐pancreas (ES: 0.33 [0.13–0.53]; I 2 = 81.76%), and lung (0.27 [0.17–0.37]; I 2 = 90.41%). The inter‐organ difference in humoral response had statistically significant difference (p‐value < .01). The meta‐analysis for humoral response with neutralization antibodies only showed very less response (Figure S5).

FIGURE 2.

Humoral response in solid organ transplantation (SOT) compared to controls

FIGURE 3.

Detailed analysis of humoral response in solid organ transplantation (SOT)

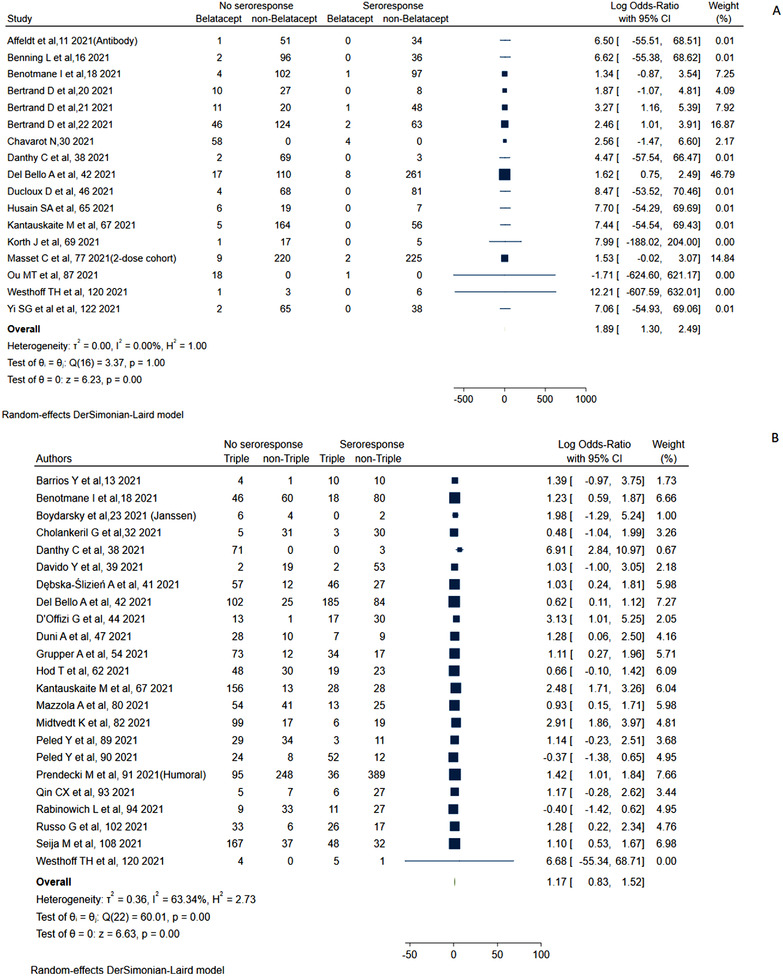

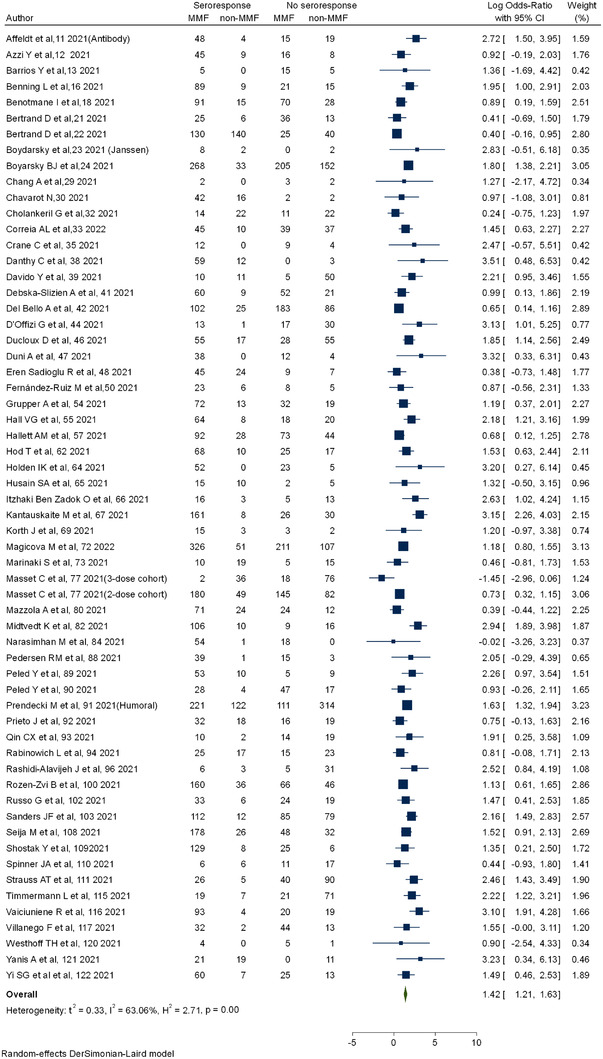

Figure 3 also shows the meta‐analysis for standard and booster dose (ES: 0.43 [0.39–0.47] vs. 0.51 [0.43–0.54]; I 2 = 70.6%) with pooled sample size of 15329 and 1693, respectively, was even though statistically significant, showed a nonsatisfactory increase of 18% with booster dose. On subgrouping the humoral response on the basis of prior COVID‐19 infection, SOT with prior infection (ES: 0.94 [0.92–0.96] vs. ES: 0.40 [0.39–0.41]; p‐value < .01) had exceptionally higher immune response compared to naïve in 2309 and 13430 cases, respectively. The response rate for mRNA‐12723 mRNA, BNT162b2 vaccine, ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19 vaccine, and inactivated whole‐virus arranged in decreasing order of responsiveness was 0.52 (0.40–0.64), 0.43 (0.38–0.48), 0.36 (0.14–0.57), and 0.33 (0.20–0.46). We also computed the risk factors for decreased response. The use of calineurin inhibitor (CNI) (log OR = 0.02 [0.29–0.33]; I 2 = 52.66%) was associated with marginal increased risk of nonresponse (Figure S6). CNI trough levels (Hedges's g = 0.16 [−0.28 to 0.60]; I 2 = 91.59%) were not associated with higher risk of nonresponse (Figure S7). Mycophenolic acid (MMF) (log OR = 1.42 [1.21–1.63]; I 2 = 63.06%) was associated with higher risk for nonresponse (Figure 4). Belatacept (log OR = 1.89 [1.3–2.49]; I 2 = 0.00%) use had highest risk for nonresponse (Figure 5). The presence of triple immunosuppression (log OR = 1.17 [0.83–1.52]; I 2 = 63.34%) was associated with higher risk of nonresponse (Figure 5). The regimen with mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors (log OR = −0.57 (−0.88 to −0.26); I 2 = 56.71%) had contrarily lower risk of nonresponse (Figure S8). Risk factors like history of recent antirejection therapy was also associated with decreased humoral response (Figure S10). The patients with lower eGFR (Hedges's g = −0.44 (−0.54 to 0.3 5); I 2 = 91.59%) had higher chances of nonresponse compared to a better eGFR (Figure S11).

FIGURE 4.

Humoral response with mycophenolic acid‐based regimen in solid organ transplantation (SOT)

FIGURE 5.

Humoral response with belatacept and triple immunosuppression in solid organ transplantation (SOT)

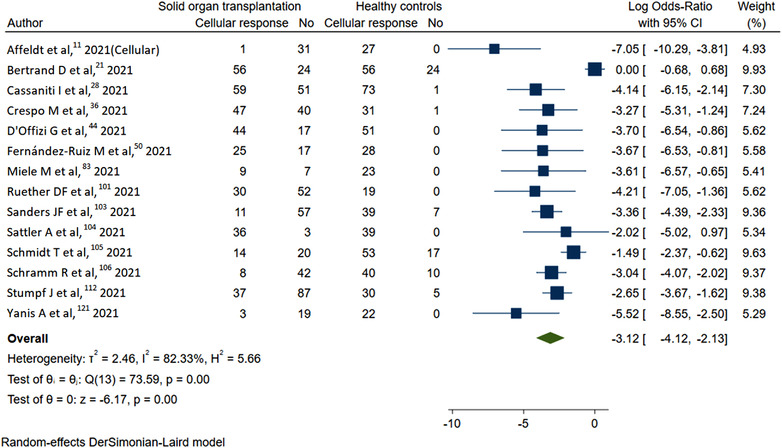

Figure 6 shows the forest plot for cellular response with COVID‐19 vaccine in SOT compared to healthy controls. The cellular response (log OR: −3.12 [−0.4.12 to −2.13] I 2 = 82.33%) was significantly lower compared to controls. All the studies with cellular response reported a lower response rate (ES: 0.42 [0.32–0.52]; I 2 = 96.8%) as shown in Figure S12. Subgroup analysis with standard and booster dosing showed no statistical difference (ES: 0.43 [0.33–0.54] vs. 0.32 [0.01–0.62]; p‐value = .48) (Figure S13). Subgroup analysis with various types of vaccines including BNT162b2 (ES: 0.42 [0.26–0.57]) and mRNA‐1273 (ES: 0.52 [0.32–0.71]) showed higher responsiveness in the latter, but there was no statistical difference between groups (Figure S14).

FIGURE 6.

Cellular response in solid organ transplantation (SOT) compared to controls

Figure S15 describes the bubble plot for meta‐regression analysis. For overall studies assessing humoral response, meta regression analysis for male sex showed a regression coefficient of −0.0001 (95% CI: −0.0002 to 0.0005; p‐value = .546) with I 2 = 95.6% and R 2 = 7.07%. Meta regression analysis for median age showed regression coefficient of −0.005 (95% CI: −0.008 to 0.001; p‐value = .012) with I 2 = 96.03% and R 2 = 0.84%. Thus, increasing age was a factor for decreased humoral response. For overall studies with cellular response, male sex showed a coefficient of regression of −0.0008 (95% CI: −0.003 to 0.001); p‐value = .36 with I 2 = 97.06% and R 2 = 0% in the meta regression analysis. For median age, the coefficient of regression reported was −0.001 (95% CI: −0.021 to 0.018); p‐value = .84 with I 2 = 96.99% and R 2 = 0%. Thus, there was no impact in cellular response with age and sex as per the analysis. Time from transplantation was not assessed, as the data were unspecified for the concerned sample size. For humoral response, meta regression analysis for years since transplantation to vaccination showed a regression coefficient of 0.008 (95% CI: −0.0022 to 0.018; p‐value = .127) with I 2 = 96.05% and R 2 = 3.41%. Thus, earlier period of transplantation showed a trend toward lower response, but the difference was not statistically significant. However, in meta‐analysis performed with early versus later period of transplant (within 1 year in most studies), there was a significant no‐seroresponse in early period of transplant (Figure S9).

Publication bias is demonstrated in Figure S16. The Egger test indicated that there was publication bias for humoral response in our meta‐analysis, while no publication bias was detected for cellular response studies. A total of 13, 11, 17, 39, and 26 studies had NOS scores of 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9, respectively (Table S5). The results of the sensitivity analysis for humoral and cellular response are depicted in Figures S17 and S18, which were consistent with that of our primary analysis, hence confirming the robustness of our findings.

4. DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta‐analysis has many highlights which are as follows: (1) The overall immunogenicity rate in the SOT was only 44% and 42% for both humoral and cellular response, respectively, which is strikingly lower compared to the general population. (2) The immunogenicity rates differ substantially with organs, where liver transplants had a relatively better response compared to kidney and heart. Lung transplant recipients had the lowest humoral response. (3) The booster dosing of vaccines does not induce a full response to vaccines in SOT. (4) SOT showed a comparatively higher response with mRNA‐1273 compared to other vaccines. (5) Lower vaccine response was shown with triple‐drugs, belatacept, and mycophenolic acid‐based regimens. (6) The older age, low eGFR of the SOT is a risk factor for a decreased response, while an early period of transplantation and history of anti‐rejection therapy, had a lower response.

Our analysis tested vaccine effectiveness but, protection from infection in the real world among SOT is limited. A recent study demonstrated inferior protection in SOT compared to the general population. 123 Furthermore, in real‐world studies, the risk of acquiring post‐vaccination COVID‐19 was relatively lower with mRNA vaccines compared to the BNT162b2 vaccine 124 This stresses the choice of vaccine used in SOT, as our report also showed varying immunogenicity with different vaccines.

Our report has analyzed humoral response with anti‐Spike protein antibodies in the majority of the cases as most studies reported the same, but neutralization antibodies have shown high predictivity for protection from symptomatic COVID‐19. 125 However, the protective levels of these antibodies in SOT would be debatable. In our systematic review, SOT has mounted further lower levels of neutralization antibodies (Figure S5) in comparison to spike protein. Thus, the seroprotection would be further diminished than the humoral response reported in our report.

The durability of vaccine effectiveness would be in focus in current practices. A recent meta‐analysis 126 has shown a waning of antibody response within 6 months, which further raises an approach of regular booster for SOT. The inter‐rim statement of WHO on December 22, 2021 stressed the potential utility of booster dosing in the omicron era. A few reports 127 , 128 measuring antibody titers following booster dose in SOT showed similar issues with fading of the immune response. Recent data 129 in the general population have confirmed that heterologous vaccine as the booster is inducing a stronger response. Our review had a few reports 78 , 97 , 107 with similar observations. The reports of inadequate response, even after vaccination with the third dose, lead to testing of the fourth dose in SOT. In the same context, a recent study 130 tested 18 SOT and showed a response of 28%, 67%, and 83% after the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th dose, respectively. The immune response to COVID‐19 vaccine is proven dose‐dependent in a recent study that showed higher dose elicits a better immune response in the general population. 131 All these reports open an area of research, which can be explored to increase the immunogenicity of the COVID‐19 vaccine among SOT.

In our review, a study 53 reported a marked increase in immune response among pretransplant patients, which bolsters the rationale of immunizing candidates before transplantation. A recent meta‐analysis 132 on hemodialysis patients showed around 80% immune response, which is double our report in SOT. This comparison further pushes the rationale to mandate vaccination before transplantation as a policy in transplantation practices.

Our analysis has shown considerably lower response with maintenance therapy of Belatacept and mycophenolic acid; however the rationale to modify these drugs to augment the immunogenicity is tricky and warrants a rigorous safety analysis.

The study has some inherent limitations. Firstly, the majority of the studies had around 4 weeks duration from the last vaccine dose to testing. Still, there was wide variation in the reports. Sero‐responsiveness in the SOT host may relate to time from vaccination, and so if serologies were performed early after vaccination, they may be falsely negative. Secondly, there was a wide array of tests performed in different parts of the world to study immunogenicity, which is understandable in the unprecedented era of the pandemic. Thirdly, there could be an overlapping of cases from the same investigating centers, despite our efforts to exclusion of any such studies. Another limitation of our report is that the side effect profiles of vaccines and boosters are not studied, but the rationale was the extensive and ensuring safety reports for COVID‐19 vaccines in the general population. 133 A recent study reporting reactogenicity of booster doses in SOT 134 also demonstrated the safety of vaccines, which further supported our exclusion. Also, the data for multiorgan transplant and non‐mRNA‐based vaccines were less reported, so the results regarding them would be inconclusive.

In a nutshell, our report focuses on continued research for developing a strategy for effective vaccination among SOT for future preparedness for the pandemic.

5. CONCLUSION

This systematic review and meta‐analysis found that patients with SOT had an immunogenicity rate of only around 40%, for both humoral and cellular response. The increase in immune response following a booster dose is important, and additional doses are the need of the hour in SOT. Immunosuppression like mycophenolic acid and belatacept has a significant impact on vaccine response. Immunizing SOT with higher efficacy vaccines, higher doses, heterologous booster doses, and regular dosing are important procedures that can increase the response. Further investigations and research are needed to implement modified vaccine protocols among SOT.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed equally to the conception, design of the work, acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Supporting information

Supplement Material

Graphical Abstract

Meshram HS, Kute V, Rane H, et al. Humoral and cellular response of COVID‐19 vaccine among solid organ transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2022;e13926. 10.1111/tid.13926

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used for meta‐analysis will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wouters OJ, Shadlen KC, Salcher‐Konrad M, et al. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID‐19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet. 2021;397:P1023‐P1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jager KJ, Kramer A, Chesnaye NC, et al. Results from the ERA‐EDTA Registry indicate a high mortality due to COVID‐19 in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients across Europe. Kidney Int. 2020;98(6):1540‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kute VB, Tullius SG, Rane H, Chauhan S, Mishra V, Meshram HS. Global impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on solid organ transplant. Transplant Proc. 2022:S0041‐1345(22)00132‐4. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2022.02.009. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35337665; PMCID: PMC8828418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pormohammad A, Zarei M, Ghorbani S, et al. Efficacy and safety of COVID‐19 vaccines: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. Vaccines. 2021;9(5):467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pormohammad A, Zarei M, Ghorbani S, et al. Efficacy and safety of COVID‐19 vaccines: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(5):467. 10.3390/vaccines9050467. PMID: 34066475; PMCID: PMC8148145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sun J, Zheng Q, Madhira V, et al. Association between immune dysfunction and COVID‐19 breakthrough infection after SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;182(2):153‐162. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.7024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Embi PJ, Levy ME, Naleway AL, et al. Effectiveness of 2‐dose vaccination with mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines against COVID‐19‐associated hospitalizations among immunocompromised adults ‐ nine states, January‐September 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(44):1553‐1559. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7044e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brooke BS, Schwartz TA, Pawlik TM. MOOSE reporting guidelines for meta‐analyses of observational studies. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(8):787‐788. 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta‐analyses. Accessed 28 December, 2021. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 10. Higgins JPT, Li T, Deeks JJ. Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0. Cochrane; 2019. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter‐06#section‐6‐5‐2 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Affeldt P, Koehler FC, Brensing KA, et al. Immune responses to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and vaccination in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients. Microorganisms. 2022;10(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Azzi Y, Raees H, Wang T, et al. Risk factors associated with poor response to COVID‐19 vaccination in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2021;100(5):1127‐1128. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barrios Y, Rodriguez A, Franco A, et al. Optimizing a protocol to assess immune responses after SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in Kidney‐transplanted patients: in vivo DTH cutaneous test as the initial screening method. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(11):1315. 10.3390/vaccines9111315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ben‐Dov IZ, Oster Y, Tzukert K, et al. Impact of tozinameran (BNT162b2) mRNA vaccine on kidney transplant and chronic dialysis patients: 3–5 months follow‐up. J Nephrol. 2022;35(1):153‐164. 10.1007/s40620-021-01210-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benning L, Morath C, Bartenschlager M, et al. Natural SARS‐CoV‐2 infection results in higher neutralization response against variants of concern compared to two‐dose BNT162b2 vaccination in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2021;101(3):639‐642. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Benning L, Morath C, Bartenschlager M, et al. Neutralization of SARS‐CoV‐2 variants of concern in kidney transplant recipients after standard COVID‐19 vaccination [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 22]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17(1):98‐106. 10.2215/CJN.11820921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Benotmane I, Gautier G, Perrin P, Olagne J, Cognard N, Fafi‐Kremer S, Caillard S. Antibody response after a third dose of the mRNA‐1273 SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients with minimal serologic response to 2 doses. JAMA. 2021;326(11):1063‐1065. 10.1001/jama.2021.12339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Benotmane I, Gautier‐Vargas G, Cognard N, et al. Low immunization rates among kidney transplant recipients who received 2 doses of the mRNA‐1273 SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine. Kidney Int. 2021;99(6):1498‐1500. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bergman P, Blennow O, Hansson L, et al. Safety and efficacy of the mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS‐CoV‐2 in five groups of immunocompromised patients and healthy controls in a prospective open‐label clinical trial [published online ahead of print, 2021 Nov 29]. EBioMedicine. 2021;74:103705. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bertrand D, Hamzaoui M, Lemée V, et al. Antibody and T cell response to SARS‐CoV‐2 messenger RNA BNT162b2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients and hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(9):2147‐2152. 10.1681/ASN.2021040480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bertrand D, Hamzaoui M, Lemée V, et al. Antibody and T‐cell response to a third dose of SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2021;100(6):1337‐1340. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bertrand D, Hanoy M, Edet S, et al. Antibody response to SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients and in‐centre and satellite centre haemodialysis patients. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(9):2127‐2128. 10.1093/ckj/sfab100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boyarsky BJ, Chiang TP, Ou MT, et al. Antibody response to the Janssen COVID‐19 vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2021;105(8):e82‐e83. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boyarsky BJ, Werbel WA, Avery RK, et al. Antibody response to 2‐dose SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccine series in solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA. 2021;325(21):2204‐2206. 10.1001/jama.2021.7489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bruminhent J, Setthaudom C, Chaumdee P, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific humoral and cell‐mediated immune responses after immunization with inactivated COVID‐19 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients (CVIM 1 study) [published online ahead of print, 2021 Oct 17]. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(3):813‐822. 10.1111/ajt.16867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Buchwinkler L, Solagna CA, Messner J, Pirklbauer M, Rudnicki M, Mayer G, Kerschbaum J. Antibody response to mRNA vaccines against SARS‐CoV‐2 with chronic kidney disease, hemodialysis, and after kidney transplantation. J Clin Med. 2022;11(1):148. 10.3390/jcm11010148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cao J, Liu X, Muthukumar A, Gagan J, Jones P, Zu Y. Poor humoral response in solid organ transplant recipients following complete mRNA SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination. Clin Chem. 2021;68(1):251‐253. 10.1093/clinchem/hvab149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cassaniti I, Bergami F, Arena F, et al. Immune response to BNT162b2 in solid organ transplant recipients: negative impact of mycophenolate and high responsiveness of SARS‐CoV‐2 recovered subjects against delta variant. Microorganisms. 2021;9(12):2622. 10.3390/microorganisms9122622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang A, Alejo JL, Abedon AT, et al. Antibody response to an mRNA SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine following initial vaccination with Ad.26.COV2.S in solid organ transplant recipients: a case series [published online ahead of print, 2021 Nov 16]. Transplantation. 2022;106(2):e161‐e162. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chavarot N, Morel A, Leruez‐Ville M, et al. Weak antibody response to three doses of mRNA vaccine in kidney transplant recipients treated with belatacept. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(12):4043‐4051. 10.1111/ajt.16814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chavarot N, Ouedrani A, Marion O, et al. Poor anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 humoral and T‐cell responses After 2 injections of mRNA vaccine in kidney transplant recipients treated with belatacept. Transplantation. 2021;105(9):e94‐e95. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cholankeril G, Al‐Hillan A, Tarlow B, et al. Clinical factors associated with lack of serological response to SARS‐CoV‐2 messenger RNA vaccine in liver transplantation recipients. Liver Transpl. 2022;28(1):123‐126. 10.1002/lt.26351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Correia AL, Leal R, Pimenta AC, et al. The type of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine influences serological response in kidney transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jan 8]. Clin Transplant. 2022;36:e14585. 10.1111/ctr.14585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cotugno N, Pighi C, Morrocchi E, et al. BNT162B2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine in heart and lung transplanted young adults: Is an alternative SARS‐CoV‐2 immune response surveillance needed? [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 21]. Transplantation. 2022;106(2):e158‐e160. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crane C, Phebus E, Ingulli E. Immunologic response of mRNA SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in adolescent kidney transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2021 Sep 15]. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022;37(2):449‐453 . 10.1007/s00467-021-05256-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crespo M, Barrilado‐Jackson A, Padilla E, et al. Negative immune responses to two‐dose mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines in renal allograft recipients assessed with simple antibody and interferon gamma release assay cellular monitoring [published online ahead of print, 2021 Sep 22]. Am J Transplant. 2021. 10.1111/ajt.16854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cucchiari D, Egri N, Bodro M, et al. Cellular and humoral response after MRNA‐1273 SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(8):2727‐2739. 10.1111/ajt.16701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Danthu C, Hantz S, Dahlem A, Duval M, Ba B, Guibbert M, El Ouafi Z, Ponsard S, Berrahal I, Achard JM, Bocquentin F, Allot V, Rerolle JP, Alain S, Touré F. Humoral response after SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccination in a cohort of hemodialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(9):2153‐2158. 10.1681/ASN.2021040490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Davidov Y, Tsaraf K, Cohen‐Ezra O, et al. Immunogenicity and adverse effects of the 2‐Dose BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccine among liver transplantation recipients [published online ahead of print, 2021 Nov 12]. Liver Transpl. 2021. 10.1002/lt.26366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dębska‐Ślizień A, Muchlado M, Ślizień Z, et al. Significant humoral response to mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients with prior exposure to SARS‐CoV‐2. The COViNEPH Project [published online ahead of print, 2021 Nov 23]. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2021;. doi: 10.20452/pamw.16142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dębska‐Ślizień A, Ślizień Z, Muchlado M, et al. Predictors of humoral response to mRNA COVID19 vaccines in kidney transplant recipients: a longitudinal study‐the COViNEPH project. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(10):1165. 10.3390/vaccines9101165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Del Bello A, Abravanel F, Marion O, et al. Efficiency of a boost with a third dose of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 messenger RNA‐based vaccines in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(1):322‐323. 10.1111/ajt.16775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Devresse A, Saad Albichr I, Georgery H, et al. T‐cell and antibody response after 2 doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine in a belgian cohort of kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2021;105(10):e142‐e143. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. D'Offizi G, Agrati C, Visco‐Comandini U, et al. Coordinated cellular and humoral immune responses after two‐dose SARS‐CoV2 mRNA vaccination in liver transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2021 Oct 31]. Liver Int. 2021. 10.1111/liv.15089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dolff S, Zhou B, Korth J, et al. Evidence of cell‐mediated immune response in kidney transplants with a negative mRNA vaccine antibody response. Kidney Int. 2021;100(2):479‐480. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ducloux D, Colladant M, Chabannes M, Bamoulid J, Courivaud C. Factors associated with humoral response after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccination in kidney transplant patients. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(10):2270‐2272. 10.1093/ckj/sfab125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Duni A, Markopoulos GS, Mallioras I, et al. The humoral immune response to BNT162b2 vaccine is associated with circulating CD19+ B lymphocytes and the Naïve CD45RA to Memory CD45RO CD4+ T helper cells ratio in hemodialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients. Front Immunol. 2021;12:760249. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.760249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Eren Sadioğlu R, Demir E, Evren E, et al. Antibody response to two doses of inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine (CoronaVac) in kidney transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2021;23(6):e13740. 10.1111/tid.13740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Erol Ç, Yanık Yalçın T, Sarı N, et al. Differences in antibody responses between an inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine and the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine in solid‐organ transplant recipients. Exp Clin Transplant. 2021;19(12):1334‐1340. 10.6002/ect.2021.0402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fernández‐Ruiz M, Almendro‐Vázquez P, Carretero O, et al. Discordance between SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific cell‐mediated and antibody responses elicited by mRNA‐1273 vaccine in kidney and liver transplant recipients. Transplant Direct. 2021;7(12):e794. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ferreira VH, Marinelli T, Ierullo M, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection induces greater T‐cell responses compared to vaccination in solid organ transplant recipients. J Infect Dis. 2021;224(11):1849‐1860. 10.1093/infdis/jiab542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Firket L, Descy J, Seidel L, et al. Serological response to mRNA SARS‐CoV‐2 BNT162b2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients depends on prior exposure to SARS‐CoV‐2. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(11):3806‐3807. 10.1111/ajt.16726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Grupper A, Katchman E, Ben‐Yehoyada M, et al. Kidney transplant recipients vaccinated before transplantation maintain superior humoral response to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine. Clin Transplant. 2021;35(12):e14478. 10.1111/ctr.14478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Grupper A, Rabinowich L, Schwartz D, et al. Reduced humoral response to mRNA SARS‐CoV‐2 BNT162b2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients without prior exposure to the virus. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(8):2719‐2726. 10.1111/ajt.16615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hall VG, Ferreira VH, Ierullo M, et al. Humoral and cellular immune response and safety of two‐dose SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA‐1273 vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(12):3980‐3989. 10.1111/ajt.16766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hall VG, Ferreira VH, Ku T, et al. Randomized trial of a third dose of mRNA‐1273 vaccine in transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(13):1244‐1246. 10.1056/NEJMc2111462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hallett AM, Greenberg RS, Boyarsky BJ, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 messenger RNA vaccine antibody response and reactogenicity in heart and lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40(12):1579‐1588. 10.1016/j.healun.2021.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Haskin O, Ashkenazi‐Hoffnung L, Ziv N, et al. Serological response to the BNT162b2 COVID‐19 mRNA vaccine in adolescent and young adult kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2021;105(11):e226‐e233. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Havlin J, Skotnicova A, Dvorackova E, et al. Impaired humoral response to third dose of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine despite detectable spike protein‐specific t cells in lung transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2021 Nov 24]. Transplantation. 2021. 10.1097/TP.0000000000004021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Havlin J, Svorcova M, Dvorackova E, et al. Immunogenicity of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40(8):754‐758. 10.1016/j.healun.2021.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Herrera S, Colmenero J, Pascal M, et al. Cellular and humoral immune response after mRNA‐1273 SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in liver and heart transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(12):3971‐3979. 10.1111/ajt.16768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hod T, Ben‐David A, Olmer L, et al. Humoral response of renal transplant recipients to the BNT162b2 SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccine using both RBD IgG and neutralizing antibodies. Transplantation. 2021;105(11):e234‐e243. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hoffman TW, Meek B, Rijkers GT, van Kessel DA. Poor serologic response to 2 doses of an mRNA‐based SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in lung transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2022;106(1):e103‐e104. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Holden IK, Bistrup C, Nilsson AC, et al. Immunogenicity of SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients. J Intern Med. 2021;290(6):1264‐1267. 10.1111/joim.13361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Husain SA, Tsapepas D, Paget KF, et al. Postvaccine Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein antibody development in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(6):1699‐1700. 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Itzhaki Ben Zadok O, Shaul AA, Ben‐Avraham B, et al. Immunogenicity of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine in heart transplant recipients ‐ a prospective cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(9):1555‐1559. 10.1002/ejhf.2199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kantauskaite M, Müller L, Kolb T, et al. Intensity of mycophenolate mofetil treatment is associated with an impaired immune response to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in kidney transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2021 Sep 22]. Am J Transplant. 2021. 10.1111/ajt.16851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Karaba AH, Zhu X, Liang T, et al. A THIRD DOSE OF SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine increases neutralizing antibodies against variants of concern in solid organ transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 24]. Am J Transplant. 2021. 10.1111/ajt.16933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Korth J, Jahn M, Dorsch O, et al. Impaired humoral response in renal transplant recipients to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination with BNT162b2 (Pfizer‐BioNTech). Viruses. 2021;13(5):756. 10.3390/v13050756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kumar D, Ferreira VH, Hall VG, et al. Neutralization of SARS‐CoV‐2 variants in transplant recipients after two and three doses of mRNA‐1273 vaccine: secondary analysis of a randomized trial [published online ahead of print, 2021 Nov 23]. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(2):226‐233. 10.7326/M21-3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kute VB, Shah N, Meshram HS, et al. Safety and efficacy of Oxford vaccine in kidney transplant recipients: a single‐center prospective analysis from India [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 19]. Nephrology (Carlton). 2021. 10.1111/nep.14012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Magicova M, Zahradka I, Fialova M, et al. Determinants of immune response to Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccines in kidney transplant recipients: a prospective cohort study [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jan 6]. Transplantation. 2022. 10.1097/TP.0000000000004044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Marinaki S, Adamopoulos S, Degiannis D, et al. Immunogenicity of SARS‐CoV‐2 BNT162b2 vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(8):2913‐2915. 10.1111/ajt.16607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Marion O, Del Bello A, Abravanel F, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 messenger RNA vaccines in recipients of solid organ transplants. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(9):1336‐1338. 10.7326/M21-1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Marlet J, Gatault P, Maakaroun Z, et al. Antibody responses after a third dose of COVID‐19 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients and patients treated for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(10):1055. 10.3390/vaccines9101055. PMID: 34696163; PMCID: PMC8539204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Massa F, Cremoni M, Gérard A, et al. Safety and cross‐variant immunogenicity of a three‐dose COVID‐19 mRNA vaccine regimen in kidney transplant recipients. EBioMedicine. 2021;73:103679. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Masset C, Kerleau C, Garandeau C, et al. A third injection of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients improves the humoral immune response. Kidney Int. 2021;100(5):1132‐1135. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Masset C, Ville S, Garandeau C, et al. Observations on improving COVID‐19 vaccination responses in kidney transplant recipients: heterologous vaccination and immunosuppression modulation [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 8]. Kidney Int. 2021;101(3):642‐645. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Matsunami M, Suzuki T, Terao T, Kuji H, Matsue K. Immune response to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination among renal replacement therapy patients with CKD: a single‐center study [published online ahead of print, 2021 Nov 8]. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2021;1‐3. 10.1007/s10157-021-02156-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mazzola A, Todesco E, Drouin S, et al. Poor antibody response after two doses of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2021 Jun 24]. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciab580. 10.1093/cid/ciab580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Medina‐Pestana J, Covas DT, Viana LA, et al. Inactivated Whole‐virus vaccine triggers low response against SARS‐CoV‐2 infection among renal transplant patients: Prospective Phase 4 study results [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 7]. Transplantation. 2021. 10.1097/TP.0000000000004036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Midtvedt K, Tran T, Parker K, et al. Low immunization rate in kidney transplant recipients also after dose 2 of the BNT162b2 vaccine: continue to keep your guard up!. Transplantation. 2021;105(8):e80‐e81. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Miele M, Busà R, Russelli G, et al. Impaired anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 humoral and cellular immune response induced by Pfizer‐BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine in solid organ transplanted patients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(8):2919‐2921. 10.1111/ajt.16702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Narasimhan M, Mahimainathan L, Clark AE, et al. Serological response in lung transplant recipients after two doses of SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccines. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(7):708. 10.3390/vaccines9070708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Nazaruk P, Monticolo M, Jędrzejczak AM, et al. Unexpectedly high efficacy of SARS‐CoV‐2 BNT162b2 vaccine in liver versus kidney transplant Recipients‐Is it related to immunosuppression only?. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(12):1454. 10.3390/vaccines9121454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Noble J, Langello A, Bouchut W, Lupo J, Lombardo D, Rostaing L. Immune response Post‐SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccination in kidney transplant recipients receiving belatacept. Transplantation. 2021;105(11):e259‐e260. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ou MT, Boyarsky BJ, Chiang TPY, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity After SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccination in kidney transplant recipients taking belatacept. Transplantation. 2021;105(9):2119‐2123. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Pedersen RM, Bang LL, Tornby DS, et al. The SARS‐CoV‐2‐neutralizing capacity of kidney transplant recipients 4 weeks after receiving a second dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine. Kidney Int. 2021;100(5):1129‐1131. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Peled Y, Ram E, Lavee J, et al. BNT162b2 vaccination in heart transplant recipients: clinical experience and antibody response. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40(8):759‐762. 10.1016/j.healun.2021.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Peled Y, Ram E, Lavee J, et al. Third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine in heart transplant recipients: immunogenicity and clinical experience [published online ahead of print, 2021 Aug 28]. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;41(2):148‐157. 10.1016/j.healun.2021.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Prendecki M, Thomson T, Clarke CL, et al. Immunological responses to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines in kidney transplant recipients. Lancet. 2021;398(10310):1482‐1484. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02096-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Prieto J, Rammauro F, López M, et al. Low IgG antibody levels against SARS‐CoV‐2 after two‐dose vaccination among liver transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 27]. Liver Transpl. 2021. 10.1002/lt.26400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Qin CX, Auerbach SR, Charnaya O, et al. Antibody response to 2‐dose SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccination in pediatric solid organ transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2021 Sep 13]. Am J Transplant. 2021. 10.1111/ajt.16841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rabinowich L, Grupper A, Baruch R, et al. Low immunogenicity to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination among liver transplant recipients. J Hepatol. 2021;75(2):435‐438. 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Rahav G, Lustig Y, Lavee J, et al. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccination in immunocompromised patients: a prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;41:101158. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Rashidi‐Alavijeh J, Frey A, Passenberg M, et al. Humoral response to SARS‐Cov‐2 vaccination in liver transplant recipients‐a single‐center experience. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(7):738. 10.3390/vaccines9070738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Reindl‐Schwaighofer R, Heinzel A, Mayrdorfer M, et al. Comparison of SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody response 4 weeks after homologous vs heterologous third vaccine dose in kidney transplant recipients: A randomized clinical trial [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 20]. JAMA Intern Med. 2021. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.7372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Reischig T, Kacer M, Vlas T, et al. Insufficient response to mRNA SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine and high incidence of severe COVID‐19 in kidney transplant recipients during pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 3]. Am J Transplant. 2021. 10.1111/ajt.16902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Rincon‐Arevalo H, Choi M, Stefanski AL, et al. Impaired humoral immunity to SARS‐CoV‐2 BNT162b2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients and dialysis patients. Sci Immunol. 2021;6(60):eabj1031. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abj1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Rozen‐Zvi B, Yahav D, Agur T, et al. Antibody response to SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccine among kidney transplant recipients: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(8):1173.e1‐1173.e4. 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ruether DF, Schaub GM, Duengelhoef PM, et al. SARS‐CoV2‐specific humoral and T‐cell immune response after second vaccination in liver cirrhosis and transplant patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):162‐172.e9. 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Russo G, Lai Q, Poli L, et al. SARS‐COV‐2 vaccination with BNT162B2 in renal transplant patients: Risk factors for impaired response and immunological implications [published online ahead of print, 2021 Sep 26]. Clin Transplant. 2021;e14495. 10.1111/ctr.14495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Sanders JF, Bemelman FJ, Messchendorp AL, et al. The RECOVAC immune‐response study: the immunogenicity, tolerability, and safety of COVID‐19 vaccination in patients with chronic kidney disease, on dialysis, or living with a kidney transplant [published online ahead of print, 2021 Nov 9]. Transplantation. 2021. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Sattler A, Schrezenmeier E, Weber UA, et al. Impaired humoral and cellular immunity after SARS‐CoV‐2 BNT162b2 (tozinameran) prime‐boost vaccination in kidney transplant recipients. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(14):e150175. 10.1172/JCI150175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Schmidt T, Klemis V, Schub D, et al. Cellular immunity predominates over humoral immunity after homologous and heterologous mRNA and vector‐based COVID‐19 vaccine regimens in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(12):3990‐4002. 10.1111/ajt.16818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Schramm R, Costard‐Jäckle A, Rivinius R, et al. Poor humoral and T‐cell response to two‐dose SARS‐CoV‐2 messenger RNA vaccine BNT162b2 in cardiothoracic transplant recipients. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021;110(8):1142‐1149. 10.1007/s00392-021-01880-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Schrezenmeier E, Rincon‐Arevalo H, Stefanski AL, et al. B and T cell responses after a third dose of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2021 Oct 19]. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(12):3027‐3033. 10.1681/ASN.2021070966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Seija M, Rammauro F, Santiago J, Orihuela N, Zulberti C, Machado D, Recalde C, Noboa J, Frantchez V, Astesiano R, Yandián F. Comparison of antibody response to SARS‐CoV‐2 after two doses of inactivated virus and BNT162b2 mRNA vaccines in kidney transplant. Clin Kidney J. 2021;15(3):527‐533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Shostak Y, Shafran N, Heching M, et al. Early humoral response among lung transplant recipients vaccinated with BNT162b2 vaccine. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(6):e52‐e53. 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00184-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Spinner JA, Julien CL, Olayinka L, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 anti‐spike antibodies after vaccination in pediatric heart transplantation: a first report [published online ahead of print, 2021 Nov 14]. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022;41(2):133‐136. 10.1016/j.healun.2021.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Strauss AT, Hallett AM, Boyarsky BJ, et al. Antibody response to severe acute respiratory syndrome‐Coronavirus‐2 messenger RNA vaccines in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2021;27(12):1852‐1856. 10.1002/lt.26273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Stumpf J, Siepmann T, Lindner T, et al. Humoral and cellular immunity to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in renal transplant versus dialysis patients: A prospective, multicenter observational study using mRNA‐1273 or BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;9:100178. 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Stumpf J, Tonnus W, Paliege A, et al. Cellular and humoral immune responses after 3 doses of BNT162b2 mRNA SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in kidney transplant. Transplantation. 2021;105(11):e267‐e269. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Thuluvath PJ, Robarts P, Chauhan M. Analysis of antibody responses after COVID‐19 vaccination in liver transplant recipients and those with chronic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2021;75(6):1434‐1439. 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Timmermann L, Globke B, Lurje G, et al. Humoral immune response following SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in liver transplant recipients. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(12):1422. 10.3390/vaccines9121422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Vaiciuniene R, Sitkauskiene B, Bumblyte IA, et al. Immune response after SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in kidney transplant patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(12):1327. 10.3390/medicina57121327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Villanego F, Cazorla JM, Vigara LA, et al. Protecting kidney transplant recipients against SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a third dose of vaccine is necessary now [published online ahead of print, 2021 Sep 1]. Am J Transplant. 2021. 10.1111/ajt.16829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Wagner A, Jasinska J, Tomosel E, Zielinski CC, Wiedermann U. Absent antibody production following COVID19 vaccination with mRNA in patients under immunosuppressive treatments. Vaccine. 2021;39(51):7375‐7378. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.10.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Werbel WA, Boyarsky BJ, Ou MT, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a third dose of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients: a case series. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(9):1330‐1332. 10.7326/L21-0282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Westhoff TH, Seibert FS, Anft M, et al. A third vaccine dose substantially improves humoral and cellular SARS‐CoV‐2 immunity in renal transplant recipients with primary humoral nonresponse. Kidney Int. 2021;100(5):1135‐1136. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Yanis A, Haddadin Z, Spieker AJ, et al. Humoral and cellular immune responses to the SARS‐CoV‐2 BNT162b2 vaccine among a cohort of solid organ transplant recipients and healthy controls [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 14]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2021;e13772. 10.1111/tid.13772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Yi SG, Moore LW, Eagar T, et al. Risk factors associated with an impaired antibody response in kidney transplant recipients following 2 doses of the SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccine. Transplant Direct. 2021;8(1):e1257. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Callaghan CJ, Mumford L, Curtis RMK, et al. Real‐world effectiveness of the Pfizer‐BioNTech BNT162b2 and Oxford‐AstraZeneca ChAdOx1‐S vaccines against SARS‐CoV‐2 in Solid organ and islet transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jan 4]. Transplantation. 2022. 10.1097/TP.0000000000004059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Dickerman BA, Gerlovin H, Madenci AL, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA‐1273 Vaccines in U.S. Veterans [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 1]. N Engl J Med. 2021;386:105‐115. 10.1056/NEJMoa2115463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(7):1205‐1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Feikin D, Higdon MM, Abu‐Raddad LJ, et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and COVID‐19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta‐regression. Lancet. 2021. 10.2139/ssrn.3961378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Bertrand D, Lemée V, Laurent C, et al. Waning antibody response and cellular immunity 6 months after third dose SARS‐Cov‐2 mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jan 10]. Am J Transplant. 2022. 10.1111/ajt.16954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Kamar N, Abravanel F, Marion O, et al. Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein and neutralizing antibodies at one and 3 months after 3 doses of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in a large cohort of solid‐organ‐transplant patients [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jan 9]. Am J Transplant. 2022. 10.1111/ajt.16950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Schmidt T, Klemis V, Schub D, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of heterologous ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19/mRNA vaccination. Nat Med. 2021;27(9):1530‐1535. 10.1038/s41591-021-01464-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Alejo JL, Mitchell J, Chiang TP, et al. Antibody response to a fourth dose of a SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients: a case series. Transplantation. 2021;105(12):e280‐e281. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA‐1273 vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2427‐2438. 10.1056/NEJMoa2028436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Chen JJ, Lee TH, Tian YC, Lee CC, Fan PC, Chang CH. Immunogenicity rates after SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in people with end‐stage kidney disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2131749. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.31749. PMID: 34709385; PMCID: PMC8554642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Chen M, Yuan Y, Zhou Y, Deng Z, Zhao J, Feng F, Zou H, Sun C. Safety of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10(1):1‐2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Shapiro Ben David S, Shamir‐Stein N, Baruch Gez S, Lerner U, Rahamim‐Cohen D, Ekka Zohar A. Reactogenicity of a third BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine among immunocompromised individuals and seniors ‐ a nationwide survey. Clin Immunol. 2021;232:108860. 10.1016/j.clim.2021.108860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement Material

Graphical Abstract

Data Availability Statement

The data used for meta‐analysis will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.