Abstract

Objective

The clinical course of new COVID‐19 variants in adolescents is still unknown. The aim of this study is to evaluate the clinical characteristics of COVID‐19 in adolescents and compare the differences between the original version and the delta variant.

Materials and Methods

The medical records of patients aged 10−18 years treated for COVID‐19 between April 1, 2020 and March 31, 2022 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients were divided into four groups (asymptomatic, mild, moderate, and severe) for COVID‐19 severity and into two groups according to the diagnosis date (first−second year). The primary endpoint of the study was hospital admission.

Results

The mean age of patients was 171.81 ± 29.5 months, and most of them were males (n: 435, 53.3%). While the patient number was 296 (43.52%) in the first year of pandemic, it raised to 520 (54.11%) in the second year (p < 0.01). The severity of COVID‐19 was mild in 667 (81.7%) patients. In the comparison of patients according to the diagnosis date (first−second years); the parameters of anosmia, ageusia, weakness, muscle pain, vomiting, hospital admission, and length of stay in hospital were statistically different (p < 0.05). In the comparison of hospitalized patients between years, the necessity of oxygen support (p < 0.001), endotracheal intubation rates (p < 0.05), length of stay in the hospital (p < 0.001), and the severity of COVID‐19 (p < 0.05) was significantly higher in the second year.

Conclusion

The clinical course for adolescents diagnosed with COVID‐19 has linearly changed with the delta variant. Our results confirmed that the delta variant is more transmissible, requires more oxygen support, increases endotracheal intubation, and prolongs the length of stay in the hospital.

Keywords: adolescent, COVID‐19, delta variant

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 outbreak started in China in December 2019 and has spread all over the world. The World Health Organization declared the pandemic on March 11, 2020. 1 As of May 10, 2022, it had caused approximately 500 million confirmed cases and more than 6 million deaths worldwide. 2

While COVID‐19 mostly affects middle‐aged and elderly people in the early stages of the pandemic, there has been an increase in the number of pediatric cases recently. 3 Overall, there are fewer cases and deaths for children and adolescents than for adults. In cases disaggregated by age reported to WHO from December 30, 2019 to September 13, 2021; children under 5 years of age account for 1.8% (1,695,265) of global cases and 0.1% (1721) of global deaths; children aged 5−14 years accounted for 6.3% of global cases (6,020,084) and 0.1% of global deaths (1245); adolescents and young adults aged 15−24 years accounted for 14.5% (13,647,211) of global cases and 0.4% (6436) of global deaths. 4

Young children, schoolchildren, and adolescents generally have fewer and milder symptoms of COVID‐19 than adults and are less likely to experience severe COVID‐19 than adults. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 The biological mechanisms of age‐related differences in the clinical course are still under investigation, but hypotheses include differences in the functioning and maturity of immune systems in young children compared to adults. 9 For example, lung angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 receptors in children have different properties (e.g., lower binding capacity) than mature lung tissue. 5 In addition, the clinical course of new COVID‐19 variants in children and adolescents is still unknown. 3 The aim of this study is to evaluate the clinical characteristics of COVID‐19 in adolescents and compare the differences between the original version and the delta variant.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective case‐control study was carried out between April 2020 and 2022 in the Meram School of Medicine Hospital. Local ethical committee approval was obtained before starting the study (Decision no. 2022/3720).

2.1. Study design and patient selection

The medical records of patients aged 10−18 years treated at our hospital for COVID‐19 between April 1, 2020 and March 31, 2022 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with incomplete data, patients younger than 10 years and elder than 18 years were excluded from the study. The World Health Organization defined individuals between the ages of 10−19 as adolescents. 10 We excluded patients aged 19 because admission to pediatric clinics is legally limited to 18 years old in Turkey.

The diagnosis of COVID‐19 was made using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). During this period, combined nasal and throat swab samples were obtained from the patients and transferred to the medical molecular laboratory of Meram Medical Faculty within 30 min in a viral transport medium. First, manual extraction was performed for all samples in the laboratory. Amplification was performed on the obtained extract using the COVID‐19 quantitative (Q) reverse transcription‐PCR kit (Bio‐Speedy). The amplification curves obtained using the rotor gene‐q (Qiagen) device were monitored on the computer screen and evaluated according to the criteria suggested by the kit manufacturer. This kit provided rapid diagnosis using one‐step real‐time PCR‐targeting the RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase gene fragment.

The patients' demographic characteristics, medical history, diagnosis at the admission, symptoms, posterior−anterior lung X‐ray and lung computerized tomography (CT) findings, severity of COVID‐19, oxygen support requirement, invasive mechanical ventilator requirement, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, length of stay in the hospital, and mortality were recorded. Dong et al. 9 classified the severity of COVID‐19 into five groups (asymptomatic, mild, moderate, severe, and critical) according to the X‐ray and CT result combined with clinical presentation. Since the number of severe and critical patients in our study was not sufficient, we modified this classification into four groups (asymptomatic, mild, moderate, and severe). The primary endpoint of the study was hospital admission.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical package social sciences (SPSS; version 22.0 Inc.). The Kolmogorov−Smirnov test was used to determine distribution normality. Continuous data were presented as mean ± SD for normally distributed variables and as median and interquartile range for non‐normally distributed variables. Categorical data were presented as n (%). Patient divided into two groups by years (first and second year). In intergroup comparisons, χ 2 test was used for categorical variables, whereas Student's t‐test was used for continuous variables. Mann−Whitney U test was used for nonnormally distributed continuous variables and sequential variables. Spearman's correlation tests were performed for the relationship between COVID‐19 severity and the length of stay in the hospital. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

During the 2‐year period, a total of 1641 patients were diagnosed with COVID‐19 under 18 years old. Eight hundred and thirty‐three (50.7%) of them were adolescents. Seventeen patients who had missing data were excluded from the study, and, finally, 816 patients were included in the study. The mean age of patients was 171.81 ± 29.5 (min: 120, max: 216) months, and most of them were males (n: 435, 53.3%). While the patient number was 296 (43.52%) in the first year of pandemic, it raised to 520 (54.11%) in the second year (p < 0.01). Seven hundred and eighteen (88%) patients had no chronic diseases, 23 (2.8%) patients had asthma and 20 (2.5%) patients had an immune deficiency. The demographic characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population

| Number of patients | 816 |

| Age, months, mean ± SD | 171.81 ± 29.5 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 435 (53.3) |

| Female | 381 (46.7) |

| Year, n (%) | |

| 2020 | 296 (36.3) |

| 2021 | 520 (63.7) |

| Chronic disease, n (%) | |

| Had no chronic disease | 718 (88) |

| Asthma | 23 (2.8) |

| Immune deficiency | 20 (2.5) |

| Leukemia | 17 (2.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (1.2) |

| Cystic fibrosis | 2 (0.2) |

| Cerebral palsy | 8 (1) |

| Epilepsy | 10 (1.2) |

| Chronic renal failure | 5 (0.6) |

| Congenital heart disease | 3 (0.4) |

The most common symptom at admission was fever (n: 433, 53.1%), followed by cough (n: 397, 48.7%) and throat ache (n: 293, 35.9%). Anosmia was obtained in 73 (8.9%) patients and ageusia was obtained in 66 (8.1%) patients. While the most common diagnosis at the admission was upper respiratory tract infection (n: 549, 67.3%), pneumonia was diagnosed in 60 (7.4%) patients and acute gastroenteritis was diagnosed in 49 (6%) patients. The severity of COVID‐19 was mild in 667 (81.7%) patients. The majority (n: 684, 83.8%) of the patients were discharged from the pediatric COVID‐19 policlinic. One hundred and twenty‐two (15%) patients were admitted to the isolation ward and 10 (1.2%) patients were admitted to the ICU. A total of 54 (6.6%) patients required oxygen support. Among 54 patients, while nasal cannula and/or mask were enough in 41 (5%) patients, 6 (0.7%) patients were treated with noninvasive mechanical ventilation, and 7 (0.9%) patients needed invasive mechanical ventilation. Totaly 4 (0.5%) patients died during the study period. Among 4 dead patients, 2 of them has cerebral palsy, 1 of them had immunodeficiency, and 1 of them had chronic renal failure. The clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The clinical characteristics of study population

| Symptoms, n (%) | |

| Cough | 397 (48.7) |

| Throat ache | 293 (35.9) |

| Fever | 433 (53.1) |

| Anosmia | 73 (8.9) |

| Ageusia | 66 (8.1) |

| Rhinorrhea | 123 (15.1) |

| Headache | 130 (15.9) |

| Weakness | 260 (31.9) |

| Muscle pain | 176 (21.6) |

| Vomiting | 87 (10.7) |

| Diarrhea | 71 (8.7) |

| Rash | 9 (1.1) |

| Dyspnea | 76 (9.3) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Asymptomatic (screening test positivity) | 74 (9.1) |

| Just COVID‐19 spesific symptoms | 60 (7.4) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 549 (67.3) |

| Pneumonia | 60 (7.4) |

| Acute gastroenteritis | 49 (6) |

| Sinusitis | 9 (1.1) |

| Tuberculosis reactivation | 9 (1.1) |

| Neutropenic fever | 2 (0.2) |

| Sepsis | 3 (0.4) |

| Febrile convulsion | 1 (0.1) |

| Severity of COVID‐19, n (%) | |

| 0 = asymptomatic (screening test positivity) | 76 (9.3) |

| 1 = mild | 667 (81.7) |

| 2 = moderate | 44 (5.4) |

| 3 = severe | 29 (3.6) |

| Prognosis, n (%) | |

| Discharged from the pediatric COVID‐19 policlinic | 684 (83.8) |

| Admission to the hospital | 132 (16.2) |

| Isolation ward | 122 (15) |

| Intensive care unit | 10 (1.2) |

| Length of stay of hospitalized patients, days, median (IQR) | 6 (6) |

| Necessity of oxygen support, n (%) | 54 (6.6) |

| Nasal cannula/mask | 41 (5) |

| BPAP/CPAP | 6 (0.7) |

| Endotracheal intubation | 7 (0.9) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 4 (0.5) |

Note: Data were presented as numbers (%) except for the length of stay in the hospital.

Abbreviations: BPAP, bilevel positive airway pressure; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; IQR: interquartile range.

In the comparison of the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients according to the diagnosis date (first−second year); while anosmia, ageusia, weakness, muscle pain, and hospital admission were significantly higher in the first year (p < 0.05) the length of stay in hospital was statistically higher in the second year (p < 0.05). All other parameters were statistically similar between first and second years (p > 0.05). The comparison is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The comparison of patients according to the diagnosis date

| First year | Second year | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient number, n (%) | 296 (43.52) | 520 (54.11) | 0.005 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 157 (53) | 278 (53.5) | 0.908 |

| Age, months, mean ± SD | 170.69 ± 28.87 | 172.44 ± 29.86 | 0.415 |

| Presence of any chronic disease, n (%) | 30 (10.1) | 68 (13.1) | 0.214 |

| Symptoms, n (%) | |||

| Cough | 155 (52.4) | 242 (46.5) | 0.109 |

| Throat ache | 100 (33.8) | 193 (37.1) | 0.340 |

| Fever | 159 (53.7) | 274 (52.7) | 0.778 |

| Anosmia | 37 (12.5) | 36 (6.9) | 0.007 |

| Ageusia | 34 (11.5) | 32 (6.2) | 0.007 |

| Rhinorrhea | 37 (12.5) | 86 (16.5) | 0.121 |

| Headache | 43 (14.5) | 87 (16.7) | 0.408 |

| Weakness | 118 (39.9) | 142 (27.3) | <0.000 |

| Muscle pain | 78 (26.4) | 98 (18.8) | 0.012 |

| Vomiting | 14 (4.7) | 73 (14) | <0.000 |

| Diarrhea | 27 (9.1) | 44 (8.5) | 0.748 |

| Rash | 2 (0.7) | 7 (1.3) | 0.500 |

| Dyspnea | 28 (9.5) | 48 (9.2) | 0.914 |

| Severity of COVID‐19, n (%) | 0.260 | ||

| 0 = asymptomatic (screening test positivity) | 22 (7.4) | 54 (10.4) | |

| 1 = mild | 246 (83.1) | 421 (81) | |

| 2 = moderate | 15 (5.1) | 29 (5.6) | |

| 3 = severe | 13 (4.4) | 16 (3.1) | |

| Admission to the hospital, n (%) | 70 (23.6) | 62 (11.9) | <0.000 |

| Admission to the intensive care unit, n (%) | 3 (1) | 7 (1.3) | 1 |

| Length of stay of hospitalized patients, days, median (IQR) | 3 (6) | 7 (6) | <0.000 |

| Necessity of oxygen support, n (%) | 17 (5.7) | 37 (7.1) | 0.448 |

| Endotracheal intubation, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 6 (1.2) | 0.432 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.6) | 1 |

Note: Bold values indicates statistical significance p < 0.05.

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

In the comparison of hospitalized patients between years, the necessity of oxygen support (p < 0.001), endotracheal intubation rates (p < 0.05), and length of stay in the hospital (p < 0.001) was significantly higher in the second year. In addition, the severity of COVID‐19 was significantly higher in the second year (p < 0.05). The comparison is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The comparison of hospitalized patients according to the diagnosis date

| First year (n: 70) | Second year (n: 62) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 34 (48.6) | 27 (43.5) | 0.563 |

| Age, months, mean ± SD | 167.01 ± 27.73 | 171.81 ± 30.93 | 0.350 |

| Presence of any chronic disease, n (%) | 15 (21.4) | 43 (69.4) | <0.000 |

| Severity of COVID‐19, n (%) | 0.004 a | ||

| 0 = asymptomatic (screening test positivity) | 4 (5.7) | 1 (1.6) | |

| 1 = mild | 42 (60) | 21 (33.9) | |

| 2 = moderate | 11 (15.7) | 24 (38.7) | |

| 3 = severe | 13 (18.6) | 16 (25.8) | |

| Admission to the intensive care unit, n (%) | 3 (4.3) | 4 (11.3) | 0.189 |

| Length of stay of hospitalized patients, days, median (IQR) | 3 (6) | 7 (6) | <0.000 |

| Necessity of oxygen support, n (%) | 17 (24.3) | 37 (59.7) | <0.000 |

| Endotracheal intubation, n (%) | 1 (1.4) | 6 (9.7) | 0.035 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (4.8) | 0.341 |

Note: Bold values indicates statistical significance p < 0.05.

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Mild group is statistically significantly lower in the second year.

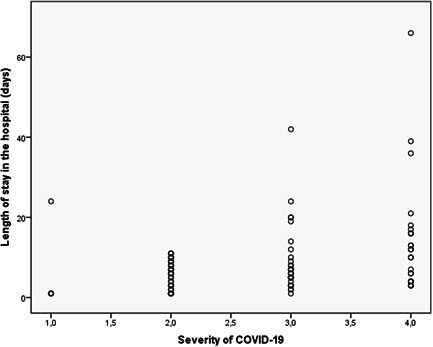

There was a significant correlation between the severity of COVID‐19 and the length of stay in the hospital (correlation coefficient = 0.683 and p < 0.001). The dot diagram of this correlation showed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The dot diagram of correlation between COVID‐19 severity and length of stay in the hospital

4. DISCUSSION

Our results showed that although the number of patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 in the second year is higher than the first year, the number of inpatients was statistically significantly higher in the first year than the second year. On the other hand, the length of stay in hospital is higher in the second year. The incidence of all symptoms in our patients were similar to the literatüre. 11 , 12 Symptoms specific to COVID‐19 such as anosmia and ageusia were more common in the first year, but no difference was found in respiratory symptoms between years. While there is no difference in respiratory symptoms, the necessity of oxygen support, endotracheal intubation, and mortality rates, the decrease in hospitalization rate is an important debate.

Since the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic, it is known that the symptomatic infection rate of children is lower than adults. Pediatric clinical manifestations are not typical and are mainly milder, compared with those of adult patients. 12 The increase in the number of COVID‐19 positive patients between years can be explained by the end of the lockdowns and the restart of education in schools. SARS‐CoV‐2 is transmitted mainly through respiratory droplets and close contact(s). The presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 in relatively closed environments with prolonged exposure to high concentrations of aerosols may also facilitate transmission. More specifically, the air‐tightness of the environment and the density of viruses per unit volume can affect the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2. 13 , 14 Although the use of masks is mandatory in schools, students and even teachers may have bent this rule and contributed to the faster spread of SARS‐CoV‐2. On the other hand, the main cause of this increase may be the delta variant, which was much more transmissible than the original version of the virus. It is known that the transmission rate of the delta variant is faster up to 60% than the original version. 15 , 16 In addition, the decrease in anosmia incidence can support our delta variant hypothesis because it is less likely to cause anosmia when compared with other variants. 17

The delta variant was first described in December 2020 in India, became widespread in February 2021, and became the dominant strain in August 2021. 18 It has a significantly higher risk of hospitalization, ICU admission, developing pneumonia, and death compared to nonvariant SARS‐CoV‐2. 19 Although the number of inpatients has decreased, it seems the delta variant is directly related to the high severity of COVID‐19, the increased necessity of oxygen support, and the increased endotracheal intubation rate in our hospitalized patients. In addition, it is not surprising that in the second year, when children have not yet been vaccinated and the delta variant is dominant, 69.4% of hospitalized patients have a chronic disease. On the other hand, patients with mild symptoms who were considered eligible for hospitalization in the early pandemic, because the progression of the disease was unknown, were not hospitalized in the second year of the pandemic. This situation may have contributed to our hospitalized patients' results.

5. CONCLUSION

As a result, the clinical course for adolescents diagnosed with COVID‐19 has linearly changed with the delta variant. Our results confirmed that the delta variant is more transmissible, requires more oxygen support, increases endotracheal intubation, and prolongs the length of stay in the hospital.

This study has some limitations. Our hospital is not the only hospital serving COVID‐19 patients. Because of this, our study population may have been relatively small and our results may not have reflected all adolescents in our city. In addition, we could not compare adolescents with other age groups, especially with adults. This may be the main subject of another research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have made substantial contributions to all of the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare conflict of interest.

Çağlar HT, Pekcan S, Yılmaz Aİ, et al. Delta variant effect on the clinical course of adolescent COVID‐19 patients. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2022;1‐7. 10.1002/ppul.26166

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO announces COVID‐19 outbreak a pandemic. 2022. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO coronavirus (COVID‐19) dashboard. 2022. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://covid19.who.int/

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO) . COVID‐19 disease in children and adolescents: scientific brief. 2022. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Children_and_adolescents-2021.1

- 4. World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO coronavirus (COVID‐19) dashboard with vaccination data. 2022. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://covid19.who.int/

- 5. Mustafa NM, A Selim L. Characterisation of COVID‐19 pandemic in paediatric age group: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoang A, Chorath K, Moreira A, et al. COVID‐19 in 7780 pediatric patients: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;24:100433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu W, Zhang Q, Chen J, et al. Detection of Covid‐19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(14):1370‐1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morand A, Fabre A, Minodier P, et al. COVID‐19 virus and children: what do we know. Arch Pediatr. 2020;27(3):117‐118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID‐19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20200702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. WHO . Adolescent health topics. 2022. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health/#tab=tab_1

- 11. Cao Q, Chen Y, Chen C, Chiu C. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in children: transmission dynamics and clinical charateristics. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119:670‐673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu X, Zhang L, Du H, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in children. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):1663‐1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China . Diagnosis and treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia (trial version 7 revised version). 2022. Accessed May 10, 2022. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202003/46c9294a7dfe4cef80dc7f5912eb1989.shtml

- 14. She J, Liu L, Liu W. COVID‐19 epidemic: disease characteristics in children. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):747‐754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mahase E. Delta variant: what is happening with transmission, hospital admissions, and restrictions. BMJ. 2021;373:n1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Public Health England . Variants: distribution of case data, 11 June 2021. 2022. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-variants-genomically-confirmed-casenumbers/variants-distribution-of-case-data-11-june-2021

- 17. Mahase E. Covid‐19: GPs urge government to clear up confusion over symptoms. BMJ. 2021;28(373):n1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shiehzadegan S, Alaghemand N, Fox M, Venketaraman V. Analysis of the delta variant B.1.617.2 COVID‐19. Clin Pract. 2021;11(4):778‐784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kumar S, Thambiraja TS, Karuppanan K, Subramaniam G. Omicron and delta variant of SARS‐CoV‐2: a comparative computational study of spike protein. J Med Virol. 2022;94(4):1641‐1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.