Background and Aims:

Outcomes of breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infections have not been well characterized in non‐veteran vaccinated patients with chronic liver diseases (CLD). We used the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) to describe these outcomes.

Approach and Results:

We identified all CLD patients with or without cirrhosis who had SARS‐CoV‐2 testing in the N3C Data Enclave as of January 15, 2022. We used Poisson regression to estimate incidence rates of breakthrough infections and Cox survival analyses to associate vaccination status with all‐cause mortality at 30 days among infected CLD patients. We isolated 278,457 total CLD patients: 43,079 (15%) vaccinated and 235,378 (85%) unvaccinated. Of 43,079 vaccinated patients, 32,838 (76%) were without cirrhosis and 10,441 (24%) with cirrhosis. Breakthrough infection incidences were 5.4 and 4.9 per 1000 person‐months for fully vaccinated CLD patients without cirrhosis and with cirrhosis, respectively. Of the 68,048 unvaccinated and 10,441 vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis, 15% and 3.7%, respectively, developed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. The 30‐day outcome of mechanical ventilation or death after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection for unvaccinated and vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis were 15.2% and 7.7%, respectively. Compared to unvaccinated patients with cirrhosis, full vaccination was associated with a 0.34‐times adjusted hazard of death at 30 days.

Conclusions:

In this N3C study, breakthrough infection rates were similar among CLD patients with and without cirrhosis. Full vaccination was associated with a 66% reduction in risk of all‐cause mortality for breakthrough infection among CLD patients with cirrhosis. These results provide an additional impetus for increasing vaccination uptake in CLD populations.

INTRODUCTION

The advent of safe and effective vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) has substantially altered the trajectory of the COVID‐19 pandemic. These vaccines have been demonstrated to be highly effective in both clinical trials and real‐world studies to decrease the risk of severe disease attributable to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.1–3 Nevertheless, despite these encouraging findings, patients with advanced liver disease have well‐recognized immune dysfunction with attenuated responses to other vaccines.4–6 Recent studies showed that 22.2% of patients with chronic liver diseases (CLD) who received whole‐virion SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines generated no antibody responses and that 24.0% of those who received mRNA‐based SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines generated poor (defined as <250 U/ml) antibody responses.7,8 Moreover, multiple previous studies in various large cohorts have demonstrated that SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in patients with cirrhosis is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality.9–13 These data highlight the growing importance of optimizing vaccination strategies for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in this vulnerable patient population.14

A recent study using the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Data Warehouse demonstrated that receiving an mRNA‐based COVID‐19 vaccine was associated with a 65% reduction after one dose in SARS‐CoV‐2 infections among veterans with CLD—a substantially lower reduction than that observed in the general population (95%).15 Despite this attenuated clinical response, however, SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in fully vaccinated veterans with cirrhosis was associated with a 78% reduction in mortality risk compared to unvaccinated veterans with cirrhosis.16 Although these studies demonstrated the efficacy of vaccination in patients with cirrhosis, the underlying populations were >96% male and >55% non‐Hispanic White, consistent with a veteran population.15,16

Significant knowledge gaps remain regarding COVID‐19 vaccinations in non‐veteran populations with cirrhosis. We therefore leveraged the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C), which has been described in detail,9,17–20 to address these gaps. As of January 15, 2021, 280 clinical sites had signed data transfer agreements, and 69 sites, of which 44 sites provided vaccination information, had completed data harmonization into the N3C Data Enclave: a diverse and nationally representative central repository of harmonized electronic health record (EHR) data. We used the N3C Data Enclave to answer two questions relevant to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccinations in CLD patients with cirrhosis: Do the rates of breakthrough infection (defined as SARS‐CoV‐2 infection after vaccination) differ between CLD patients with and without cirrhosis? And, what is the reduction in mortality associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination among CLD patients with cirrhosis who are infected with SARS‐CoV‐2?

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

The national COVID cohort collaborative

The N3C is a centralized, curated, harmonized, secure, and nationally representative clinical data resource with embedded analytical capabilities that has been described in detail in multiple analyses.9,17–20 The N3C Data Enclave includes EHR data of patients who were tested for SARS‐CoV‐2 or had related symptoms after January 1, 2020 with lookback data provided to January 1, 2018. All EHR data in the N3C Data Enclave are harmonized in the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) common data model, version 5.3.1.21 For all analyses, we used the deidentified version of the N3C Data Enclave, version 59, dated January 14, 2022 and accessed on January 15, 2022. To protect patient privacy, all dates in the deidentified N3C Data Enclave are uniformly shifted up to ±180 days within each data partner site. Because of the availability of vaccination data in a limited number of sites, we restricted all analyses to only those data partner sites with vaccination data.

Definitions of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection status, CLD/cirrhosis, and laboratory data

SARS‐CoV‐2 definitions were based on culture or nucleic acid amplification testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 as described in previous works.9 Given that the deidentified N3C Data Enclave contains date‐shifted data and lacks information on SARS‐CoV‐2 genomic sequencing, we could not differentiate between variants of SARS‐CoV‐2. CLD and cirrhosis definitions were based on OMOP identifiers as defined in previous work conducted with the N3C Data Enclave.9 All patients who had undergone orthotopic liver transplantation were excluded from all analyses.9 Given that dates are uniformly shifted within each data partner site in the deidentified N3C Data Enclave, we calculated a “maximum data date” to reflect the last known date of records for each site. We used this “maximum data date” to exclude patients who were vaccinated or tested for SARS‐CoV‐2 within 90 days of this date to allow for adequate follow‐up time and account for potential delays in data harmonization.

Definition of vaccination status

Vaccinations were defined based on OMOP drug exposure concepts delineated in vaccination studies on immunocompromised patients using the N3C Data Enclave and are provided in Table S1.19 Of note, we only included OMOP concept identifiers for the three SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination regimens with U.S. Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorizations or approvals in the USA: two mRNA vaccines from Pfizer‐BioNTech (BNT162b2) and Moderna (mRNA‐1273) and one viral vector vaccine from Johnson & Johnson/Janssen (JNJ‐784336725).1–3 All vaccines not authorized for use in the USA were excluded.

We defined “partial vaccination” as starting on day 7 after one dose of any mRNA vaccine, and we defined “full vaccination” as 14 days after the completion of the initial recommended dosing regimen for any vaccine (two doses for mRNA vaccines or one dose for viral vector vaccine). Under this commonly used definition for fully vaccinated, one dose of viral vector vaccine is equivalent to two doses of mRNA vaccines and regarded as two doses in all numerical counts of vaccination doses in summary statistics.22 Because of data limitations, we largely treated patients who received additional (“booster”) doses administered over and above full vaccination regimens as only fully vaccinated and, where possible, separately examined the effect of number of doses received. Breakthrough infections were defined as SARS‐CoV‐2 infections in partially vaccinated or fully vaccinated patients with no history of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection before vaccination.

We defined unvaccinated patients as those who did not have an associated OMOP drug exposure concept identifier for vaccination defined above (Table S1)—as such, this definition also includes patients whose vaccination status is not known within the N3C Data Enclave and may include patients who had acquired vaccinations in other venues, such as mass vaccination sites, local pharmacies, and “pop‐up” vaccination sites. In addition, patients who had acquired SARS‐CoV‐2 infection before 7 days after one dose of any mRNA vaccine or 14 days after one dose of viral vector vaccine were considered to be unvaccinated in our analyses. Patients who developed an infection before day 7 after one dose of any mRNA vaccine or day 14 after one dose of viral vector vaccine therefore did not contribute any follow‐up time to partial and full vaccination statuses.

Study design and questions of interest

Using definitions for SARS‐CoV‐2 positivity, CLD and cirrhosis, and vaccination status, we isolated our adult patient (documented age ≥ 18 years) study populations for two study questions: (1) What is the relative rate of breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infection comparing patients with and without cirrhosis who are at least partially vaccinated with no history of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection before vaccination? In this question, we sought to compare the rates of breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis versus vaccinated CLD patients without cirrhosis. (2) What is the reduction in mortality associated with vaccination among CLD patients with cirrhosis who are infected with SARS‐CoV‐2? In this question, we compared all‐cause mortality at 30 days in (partially and fully) vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis who acquired breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infection versus unvaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis who acquired SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes in our study were breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and all‐cause mortality at 30 days after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Secondary outcomes included hospitalization and mechanical ventilation within 30 days. As in previous works, the outcomes of death, mechanical ventilation, and hospitalization were centrally defined based on N3C shared logic.9,17,18

Baseline characteristics

Baseline demographic characteristics extracted from the N3C Data Enclave included age, sex, race/ethnicity, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and state of origin. States were classified into four geographical regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System.23 Patients were categorized as living in an “Other/Unknown” region if they originated from territories not otherwise classified or if state of origin was not available. We used a modified Charlson Index based on the Charlson Comorbidity Index excluding mild liver disease and severe liver disease as defined in previous analyses using N3C.9

Components of common laboratory tests (basic metabolic panel, complete blood count, liver function tests, and serum albumin) were extracted based on N3C shared logic sets except for international normalized ratio (INR), which was based on previously defined concept sets.9 We extracted the highest number of distinct laboratory values to calculate the Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease‐Sodium (MELD‐Na) score closest to, or on the index date from, within 30 days before to 7 days after the date of the earliest positive test (for SARS‐CoV‐2–infected patients) or negative test (for noninfected patients). Over half (56%) of patients had laboratory tests within 2 days of the date of the earliest positive or negative test. Of note, ~16% of CLD patients with cirrhosis in the eligible population had full laboratory data to calculate MELD‐Na scores.

Statistical analyses

Clinical characteristics and laboratory data were summarized by medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables or numbers and percentages (%) for categorical variables. Comparisons between groups were performed using Kruskal‐Wallis' and chi‐square tests, where appropriate. All patients were followed until their last recorded visit occurrence, procedure, measurement, observation, or condition occurrence in the N3C Data Enclave.

For our first analysis of breakthrough infections between vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis versus those without cirrhosis, we estimated unadjusted IRs and adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) using Poisson regression models implemented as generalized estimating equations with robust SEs.24 We calculated adjusted IRRs for partially and fully vaccinated versus unvaccinated participants to determine the association of different levels of vaccination with (breakthrough) infection. To further evaluate the effects within different strata of vaccination statuses, we created three distinct adjusted Poisson regression models to evaluate controlling for: (1) partial versus full vaccination status, (2) initial vaccination type (BNT162b2, mRNA‐1273, or JNJ‐784336725) in addition to partial versus full status, and (3) number of vaccine doses (0–4). All multivariable Poisson regression models accounted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, CLD etiology, modified Charlson scores, and region of origin.

We estimated at‐risk person‐time for unvaccinated patients by assigning “time zero” based on the first date of administration for vaccines at each data partner site and taking the difference between the time‐zero date and the event date. For vaccinated persons, at‐risk person‐time for IR estimation accrued from 7 days after the first dose of mRNA vaccines and from 14 days after the first dose of viral vector vaccines to the date of breakthrough infection, death, or last available visit occurrence date in the N3C Data Enclave (censoring). Participants contributed person‐time to partial vaccination status from 7 days after the first dose of mRNA vaccine to the 14 days after the second dose, breakthrough infection, death, or censoring in the unadjusted Poisson regression model for breakthrough infections in partially vaccinated patients. Participants contributed person‐time to full vaccination status from 14 days after the second dose of mRNA vaccine or 14 days after the first dose of viral vector vaccine to breakthrough infection, death, or censoring in the unadjusted Poisson regression for breakthrough infections in fully vaccinated patients. Of note, under these definitions, participants who received viral vector vaccines do not accumulate person‐time for partial vaccination status. For adjusted Poisson regression models evaluating all (partially and fully) vaccinated patients, participants' person‐times are sums of contributions to both partial vaccination and full vaccination statuses.

For the second analysis of all‐cause mortality in vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis with breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infections compared to unvaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis and SARS‐CoV‐2 infections, we used Cox proportional hazard models to evaluate the associations between vaccination status (partial or full vs. unvaccinated) and mortality among patients with cirrhosis who tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2.25 At‐risk person‐time for this analysis accrued from the index date of positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test to death or last available visit occurrence date in the N3C Data Enclave (censoring). Cox regression models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, CLD etiology, modified Charlson score, and region of origin.

Two‐sided p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses. Data queries, extractions, and transformations of OMOP data elements and concepts in the N3C Data Enclave were conducted using the Palantir Foundry implementations of Spark‐Python, version 3.6, and Spark‐SQL, version 3.0. Statistical analyses were performed using the Palantir Foundry implementation of Spark‐R, version 3.5.1 “Feather Spray” (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Institutional review board oversight

Submission of data from individual centers to the N3C are governed by a central institutional review board (IRB) protocol #IRB00249128 hosted at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine by the SMART IRB40 Master Common Reciprocal reliance agreement. This central IRB covers data contributions and transfer to the N3C, but does not cover research using N3C data. If elected, individual sites may choose to exercise their own local IRB agreements instead of using the central IRB. Given that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) is the steward of the repository, data received and hosted by NCATS on the N3C Data Enclave, its maintenance, and its storage are covered under a central NIH IRB protocol to make EHR‐derived data available for the clinical and research community to use for studying COVID‐19. The data within the N3C involves minimal risk to individuals and NCATS received a waiver of consent by the NIH Institutional Review Board. Our institution has an active data transfer agreement with the N3C. This specific analysis of the N3C Data Enclave was approved by the N3C under Data Use Agreements titled “[RP‐7C5E62] COVID‐19 Outcomes in Patients with Cirrhosis” and “[RP‐E77B79] COVID‐19 Outcomes in Vaccinated Patients with Liver Diseases.” Use of N3C data for this study was authorized by the IRB at the University of California–San Francisco with a waiver of consent under #21‐35861.

RESULTS

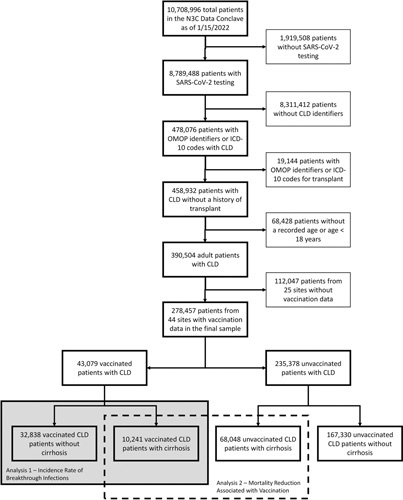

As of January 15, 2022, 69 sites that had completed data transfer were harmonized and integrated into the N3C Enclave, of which 44 sites provided vaccination information. Of the unique patients who had undergone at least one SARS‐CoV‐2 test, an eligible population of 278,457 CLD patients with or without cirrhosis regardless of vaccination status was assembled, after applying exclusion criteria for transplant status, age, and date shifting in the N3C Enclave. Patient flow and analytical samples for each of the study questions are highlighted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of isolation of CLD patients with and without cirrhosis from the main N3C cohort.

Characteristics of vaccinated CLD patients

Based on our vaccination definitions, we isolated 43,079 CLD patients who had at least one dose of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine: This represented 15.8% of the eligible population. Of these 43,079 vaccinated CLD patients, 32,838 (76.2%) did not have cirrhosis and 10,241 (23.8%) had cirrhosis. A total of 95.5% (31,344) of vaccinated CLD patients without cirrhosis and 94.8% (9711) of vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis received an mRNA vaccine as their first dose. A total of 82.9% (27,235) of vaccinated CLD patients without cirrhosis and 80.3% (8218) of vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis completed their initial vaccination series and were fully vaccinated. Baseline characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Baseline demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the 43,079 vaccinated patients with CLDs with and without cirrhosis.

| Vaccinated CLD Without Cirrhosis (n = 32,838) | Vaccinated CLD With Cirrhosis (n = 10,241) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 17,909 (55) | 4743 (46) | <0.01 |

| Age (years) | 57 (45–66) | 61 (53–69) | <0.01 |

| 18–29 | 1471 (4) | 213 (2) | |

| 30–49 | 9135 (28) | 1765 (17) | |

| 50–64 | 12,826 (39) | 4256 (42) | |

| 65+ | 9406 (29) | 4007 (39) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.01 | ||

| White | 16,528 (50) | 5690 (56) | |

| Black/African‐American | 5073 (15) | 1725 (17) | |

| Hispanic | 6938 (21) | 1851 (18) | |

| Asian | 1931 (6) | 334 (3) | |

| Unknown/Other | 2368 (7) | 641 (6) | |

| Height (cm) | 168 (160–175) | 170 (163–178) | <0.01 |

| Weight (kg) | 88 (73–104) | 83 (69–100) | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31 (27–36) | 29 (25–34) | <0.01 |

| Liver disease etiology | <0.01 | ||

| NAFLD | 22,817 (69) | 3549 (35) | |

| Hepatitis C | 6230 (19) | 2036 (20) | |

| AALD | 1205 (4) | 2995 (29) | |

| Hepatitis B | 1998 (6) | 514 (5) | |

| Cholestatic | 159 (0) | 697 (7) | |

| Autoimmune | 429 (1) | 450 (4) | |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 0 (0) | 6287 (61) | |

| Modified Charlson Indexa | 1 (0–3) | 2 (1–5) | <0.01 |

| Region | <0.01 | ||

| Northeast | 3981 (12) | 910 (9) | |

| Midwest | 5254 (16) | 2155 (21) | |

| South | 5071 (15) | 1915 (19) | |

| West | 7261 (22) | 2090 (20) | |

| Other | 11,271 (34) | 3171 (31) | |

| MELD‐Nab | 9 (7–12) | 14 (10–20) | <0.01 |

| Initial vaccine type | <0.01 | ||

| BNT162b2 | 21,040 (64) | 6909 (67) | |

| mRNA‐1273 | 10,304 (31) | 2802 (27) | |

| JNJ‐784336725 | 1494 (5) | 530 (5) | |

| Total no. of doses | <0.01 | ||

| 1 | 5603 (17) | 2023 (20) | |

| 2 | 20,923 (64) | 6418 (63) | |

| 3+ | 6312 (19) | 1800 (18) | |

| Breakthrough COVID cases | 1290 (4) | 379 (4) | 0.31 |

Note: Continuous variables are described as medians with IQRs in parentheses; ordinal and categorical variables are described as counts with percentages in parentheses.

Modified Charlson Index was calculated based on the original Charlson Comorbidity Score excluding weights for mild liver disease and severe liver disease.

MELD‐Na scores were calculated for ~16% of the total sample.

In general, compared with vaccinated CLD patients without cirrhosis, those vaccinated with cirrhosis were more likely to be older (median, 61 vs. 57 years), non‐Hispanic White (56% vs. 50%), have alcohol‐associated liver disease (AALD) as their etiology (29% vs. 4%), and have higher modified Charlson scores (median, 2 vs. 1). Vaccinated patients with cirrhosis were also less likely to be female (46% vs. 55%) compared to vaccinated patients without cirrhosis. Geographical distributions for the two populations also varied, with greater proportions of vaccinated patients with cirrhosis in the Midwest and South.

Breakthrough infection in vaccinated CLD patients

Unadjusted incidence rates (IRs) of breakthrough infections in unvaccinated, partially vaccinated, fully vaccinated, and “boosted” patients are presented in Table 2. Among fully vaccinated patients without cirrhosis, 929 breakthrough infections occurred for an estimated incidence rate (EIR) of 5.4 (95% CI, 5.1–5.8) per 1000 person‐months. Among fully vaccinated patients with cirrhosis, 254 breakthrough infections occurred for an EIR of 4.9 (95% CI, 4.4–5.6) per 1000 person‐months. Among patients without cirrhosis who received an additional or “booster” dose, 50 breakthrough infections occurred for an EIR of 8.3 (95% CI, 6.3–11.0) per 1000 person‐months. The unadjusted IR of breakthrough infections for patients with cirrhosis who received an additional or booster dose was limited by a low number of events (and could not be directly reported per N3C policy limiting reporting of cells and figures with fewer than 20 persons), but is estimated to be <9.5 per 1000 person‐months. Compared to unvaccinated patients, the overall adjusted IRRs for infection were 0.86 (95% CI, 0.75–0.99) for partially and 0.55 (95% CI, 0.52–0.58) for fully vaccinated patients.

TABLE 2. Unadjusted IRs of breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infections among vaccinated CLD patients.

| Patient Group | Total Person‐Months | No. (Breakthrough) Cases | Incidence Rate per 1000 Person‐Months (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated—overall | 1915,799 | 26,676 | 13.9 (13.8–14.1) |

| CLD without cirrhosis | 1,390,120 | 20,058 | 14.4 (14.2–14.6) |

| CLD with cirrhosis | 525,679 | 6618 | 12.6 (12.3–12.9) |

| Partial vaccination—overall | 61,344 | 421 | 6.5 (5.9–7.2) |

| CLD without cirrhosis | 46,353 | 311 | 6.4 (5.7–7.1) |

| CLD with cirrhosis | 14,991 | 110 | 7.1 (5.9–8.6) |

| Full vaccination—overall | 222,899 | 1183 | 5.3 (5.0–5.6) |

| CLD without cirrhosis | 171,561 | 929 | 5.4 (5.1–5.8) |

| CLD with cirrhosis | 51,228 | 254 | 4.9 (4.4–5.6) |

| Additional/boosted—overall | 7897 | <70a | <8.6 (6.3–10.9)a |

| CLD without cirrhosis | 5790 | 50 | 8.3 (6.3–11.0) |

| CLD with cirrhosis | 2107 | <20a | <9.5 (6.1–14.7)a |

Note: EIRs were based on unadjusted Poisson regression models with robust SEs.

N3C policy requires all cells that contain fewer than 20 persons to be reported as <20 or censored.

Among vaccinated patients, adjusted IRRs estimated from multivariable models, including (1) partial versus full vaccination status, (2) initial vaccination type, and (3) number of vaccine doses for all vaccinated patients with and without cirrhosis, are presented in Table 3. Of note, presence of cirrhosis was not associated with a higher risk of breakthrough infection when compared to those without cirrhosis in any model. Full vaccination status, defined as two or more vaccine doses, was associated with a 73% reduced risk for breakthrough infections compared with partial vaccination status. There was a dose‐dependent relationship between the number of vaccine doses and reduced risk of breakthrough infections. Moreover, compared with CLD patients who initially received BNT162b2, those who received mRNA‐1273 had an 18% reduced risk for breakthrough infections, whereas those who received JNJ‐784336725 had a 54% increased risk. Sex, age, and race/ethnicity were not significantly associated with breakthrough infections.

TABLE 3. Adjusted IRRs of clinical and demographic factors associated with breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infections.

| Adjusted IRRs (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |

| Presence of cirrhosis | |||

| CLD without cirrhosis | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| CLD with cirrhosis | 0.92 (0.81–1.05) | 0.92 (0.80–1.04) | 0.94 (0.83–1.07) |

| Vaccination status | |||

| Partial vaccination [1 dose] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | N/A |

| Full vaccination [2+ doses] | 0.27 (0.24–0.31) | 0.27 (0.24–0.30) | N/A |

| Total no. of doses | |||

| 1 | N/A | N/A | 1 [Reference] |

| 2 | N/A | N/A | 0.69 (0.59–0.81) |

| 3+ | N/A | N/A | 0.47 (0.39–0.56) |

| Initial vaccination type | |||

| BNT162b2 | N/A | 1 [Reference] | N/A |

| mRNA‐1273 | N/A | 0.82 (0.74–0.92) | N/A |

| JNJ‐784336725 | N/A | 1.54 (1.22–1.93) | N/A |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 1.01 (0.92–1.12) | 1.02 (0.92–1.12) | 1.02 (0.93–1.13) |

| Age group | |||

| 18–29 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 30–49 | 1.17 (0.88–1.57) | 1.18 (0.89–1.58) | 1.18 (0.88–1.57) |

| 50–64 | 1.02 (0.76–1.35) | 1.03 (0.77–1.37) | 0.99 (0.74–1.31) |

| 65+ | 0.84 (0.63–1.13) | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) | 0.77 (0.58–1.03) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Black | 0.99 (0.85–1.14) | 0.99 (0.86–1.15) | 0.96 (0.84–1.11) |

| Hispanic | 1.11 (0.97–1.27) | 1.13 (0.99–1.29) | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) |

| Asian | 0.92 (0.73–1.17) | 0.93 (0.74–1.18) | 0.95 (0.75–1.21) |

| Unknown/Other | 1.19 (0.98–1.43) | 1.18 (0.98–1.43) | 1.20 (0.99–1.45) |

| Liver disease etiology | |||

| NAFLD | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Hepatitis C | 0.90 (0.78–1.03) | 0.90 (0.79–1.03) | 0.92 (0.81–1.06) |

| AALD | 0.90 (0.74–1.10) | 0.90 (0.74–1.09) | 0.90 (0.74–1.09) |

| Hepatitis B | 1.05 (0.85–1.30) | 1.06 (0.86–1.32) | 1.05 (0.85–1.30) |

| Cholestatic | 0.89 (0.61–1.30) | 0.89 (0.61–1.30) | 0.90 (0.62–1.31) |

| Autoimmune | 0.64 (0.42–0.97) | 0.64 (0.42–0.97) | 0.64 (0.42–0.98) |

| Modified Charlson Indexd [per point] | 1.06 (1.05–1.08) | 1.06 (1.05–1.08) | 1.07 (1.05–1.09) |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Midwest | 1.36 (1.10–1.67) | 1.32 (1.07–1.63) | 1.49 (1.21–1.83) |

| South | 1.37 (1.11–1.70) | 1.34 (1.08–1.66) | 1.40 (1.13–1.73) |

| West | 1.47 (1.20–1.80) | 1.46 (1.19–1.78) | 1.45 (1.19–1.77) |

| Other | 1.67 (1.39–2.02) | 1.69 (1.41–2.04) | 1.57 (1.30–1.89) |

Note: EIRs were based on unadjusted Poisson regression models with robust SEs.

Model 1 was a multivariable Poisson regression model adjusting for presence of cirrhosis, partial versus full vaccination status, sex, age group, race/ethnicity, liver disease etiology, modified Charlson score, and region.

Model 2 was a multivariable Poisson regression model adjusting for all variables included in model 1 plus initial vaccination type (BNT162b2, mRNA‐1273, or JNJ‐784336725).

Model 3 was a multivariable Poisson regression model adjusting for all variables included in model 1 minus partial versus full vaccination plus the total number of doses.

Modified Charlson Index was calculated based on the original Charlson Comorbidity Score excluding weights for mild liver disease and severe liver disease.

Characteristics of unvaccinated versus vaccinated patients with cirrhosis and infected with SARS‐CoV‐2

Of the 68,048 unvaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis, 10,441 (15.3%) tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2. Of the 10,241 vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis (without previous SARS‐CoV‐2 infections before vaccination), 379 (3.7%) had a breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the 10,441 unvaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 and 379 vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis and breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infections are presented in Table 4. Compared with unvaccinated patients with cirrhosis and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, those vaccinated were older (median age, 62 vs. 59 years), taller (median height, 170 vs. 168 cm), and more likely to have other comorbid conditions (median modified Charlson score of 4 vs. 3). Vaccinated patients with cirrhosis and breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infections were less likely to have decompensated cirrhosis (64% vs. 70%) compared with unvaccinated patients with cirrhosis and SARS‐CoV‐2 infections. Of note, there were no significant differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections with regard to race/ethnicity, weight, BMI, and etiology of liver disease.

TABLE 4. Baseline demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of 10,441 unvaccinated patients with cirrhosis and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and 379 vaccinated patients with cirrhosis and breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2.

| Unvaccinated Cirrhosis With SARS‐CoV‐2 (n = 10,441) | Vaccinated Cirrhosis With Breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 (n = 379) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 4671 (45) | 183 (48) | 0.19 |

| Age (years) | 59 (49–67) | 62 (53–70) | <0.01 |

| 18–49a | 2623 (25) | 70 (18) | |

| 50–64 | 4359 (42) | 150 (40) | |

| 65+ | 3459 (33) | 159 (42) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.22 | ||

| White | 5569 (53) | 198 (52) | |

| Black/African‐American | 1742 (17) | 65 (17) | |

| Hispanic | 2130 (20) | 67 (18) | |

| Asian and Unknown/Othera | 1000 (10) | 49 (13) | |

| Height (cm) | 168 (160–178) | 170 (163–178) | 0.03 |

| Weight (kg) | 84 (70–103) | 87 (69–106) | 0.48 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30 (25–35) | 30 (25–36) | 0.80 |

| Liver disease etiology | 0.29 | ||

| NAFLD | 4324 (41) | 144 (38) | |

| Hepatitis C | 2041 (20) | 78 (21) | |

| AALD | 2711 (26) | 95 (25) | |

| Hepatitis B | 475 (5) | 25 (7) | |

| Cholestatic/autoimmunea | 890 (9) | 37 (10) | |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 7283 (70) | 240 (63) | <0.01 |

| Modified Charlson Indexb | 3 (1–6) | 4 (1–7) | <0.01 |

| Region | <0.01 | ||

| Northeast | 612 (6) | 21 (6) | |

| Midwest | 2317 (22) | 77 (20) | |

| South | 1705 (16) | 76 (20) | |

| West | 863 (8) | 66 (17) | |

| Other | 4944 (47) | 139 (37) | |

| MELD‐Nac | 17 (11–24) | 14 (10–18) | 0.01 |

| Total no. of doses | |||

| 1 | 110 (29) | ||

| 2+a | 269 (71) |

Note: Continuous variables are described as medians with IQRs in parathesis; ordinal and categorical variables are described as values with percentages in parathesis.

N3C policy requires all cells that contain fewer than 20 persons to be reported as <20 or collapsed with other categories.

Modified Charlson Index was calculated based on the original Charlson Comorbidity Score excluding weights for mild liver disease and severe liver disease.

MELD‐Na scores were calculated for ~16% of the total sample.

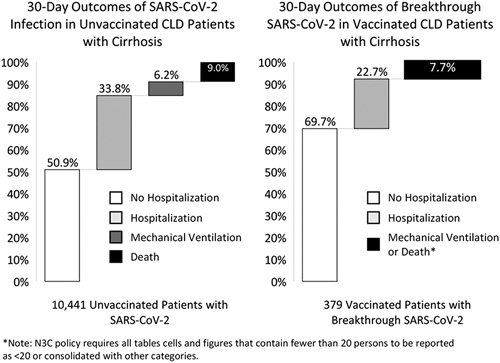

Full MELD‐Na components were available in 1689 patients, and serum albumin was available in 4996 patients; these figures respectively represented 15.6% and 46.2% of patients with both cirrhosis and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Among unvaccinated cirrhosis patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections, the median (IQR) MELD‐Na was 1710–16,18–24 and median (IQR) serum albumin was 3.2 g/dl (2.6–3.8). Among vaccinated cirrhosis patients with breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infections, median (IQR) MELD‐Na was 149–16,18 and median (IQR) serum albumin was 3.3 g/dl (2.8–3.9). Patient outcomes among unvaccinated and vaccinated patients with cirrhosis and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection are shown in Figure 2. Overall, all‐cause 30‐day mechanical ventilation (without death) and death rates after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection were 6.2% and 9.0%, respectively, among unvaccinated patients. The combined 30‐day ventilation or death rate for vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis was 7.7% (N3C policy limits reporting of cells and figures with fewer than 20 persons, therefore we combined persons who experienced mechanical ventilation [without death] or death among vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis who had breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2).

FIGURE 2.

Thirty‐day outcomes of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in unvaccinated and vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis.

Associations between vaccination and death in patients with cirrhosis infected with SARS‐CoV‐2

Demographic and clinical factors associated with all‐cause 30‐day mortality among CLD patients with cirrhosis who were infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 are presented in Table 5. In univariable Cox regression analyses, partial vaccination was not significantly associated with a reduction in all‐cause mortality at 30 days (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.43–1.72; p = 0.67) whereas full vaccination was significantly associated with a 0.39‐times hazard of death within 30 days (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.19–0.78; p < 0.01). In adjusted Cox regression analyses, partial vaccination was again not significantly associated with a reduction in all‐cause mortality at 30 days (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.78; 95% CI, 0.39–1.57; p = 0.49). Full vaccination, however, was associated with lower hazard of death within 30 days (aHR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.17–0.68; p < 0.01) in multivariable analyses. Of note, chronic hepatitis B as etiology (aHR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.95; p = 0.03), cholestatic liver diseases as etiology (aHR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.24–0.57; p < 0.01), and location in the Midwest (aHR, 0.72; 95 CI, 0.55–0.96; p = 0.02) were associated with lower 30‐day mortality hazards in multivariable analyses. Every point increase in modified Charlson score (aHR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01–1.05; p < 0.01) was associated with higher 30‐day mortality hazards in multivariable analyses. When stratified by decompensated cirrhosis, adjusted Cox regression analyses showed that full vaccination was associated with a lower hazard of death within 30 days (aHR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.19–0.83), but partial vaccination was not (aHR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.50–2.02). We were not able to conduct stratified analyses for patients with compensated cirrhosis because there was an insufficient number of events.

TABLE 5. Associations of vaccination status with all‐cause 30‐day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and infected with SARS‐CoV‐2.

| Univariable Cox Regression | Multivariable Cox Regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | aHR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Vaccination status | ||||||

| Partial vaccination | 0.86 | 0.43–1.72 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.39–1.57 | 0.49 |

| Full vaccination | 0.39 | 0.19–0.78 | <0.01 | 0.34 | 0.17–0.68 | <0.01 |

| Age (years) | 1.03 | 1.03–1.04 | <0.01 | 1.03 | 1.03–1.04 | <0.01 |

| Female | 0.85 | 0.75–0.97 | 0.02 | 0.87 | 0.76–0.99 | 0.04 |

| Race/ethnicity, no. (%) | ||||||

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Black/African‐American | 0.88 | 0.73–1.06 | 0.17 | 0.85 | 0.71–1.03 | 0.11 |

| Hispanic | 0.93 | 0.79–1.10 | 0.38 | 1.02 | 0.86–1.21 | 0.83 |

| Asian | 1.07 | 0.73–1.56 | 0.74 | 1.17 | 0.79–1.73 | 0.42 |

| Unknown/Other | 1.08 | 0.85–1.38 | 0.53 | 1.14 | 0.89–1.46 | 0.30 |

| Etiology of liver disease, no. (%) | ||||||

| NAFLD | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Hepatitis C | 0.90 | 0.76–1.07 | 0.23 | 0.87 | 0.72–1.04 | 0.11 |

| AALD | 0.88 | 0.75–1.03 | 0.11 | 0.95 | 0.80–1.12 | 0.51 |

| Hepatitis B | 0.72 | 0.51–1.01 | 0.06 | 0.67 | 0.47–0.95 | 0.03 |

| Cholestatic | 0.37 | 0.24–0.57 | <0.01 | 0.37 | 0.24–0.57 | <0.01 |

| Autoimmune | 0.88 | 0.60–1.28 | 0.50 | 0.98 | 0.67–1.43 | 0.93 |

| Modified Charlson Indexa [per point] | 1.05 | 1.04–1.07 | <0.01 | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | <0.01 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Midwest | 0.66 | 0.50–0.86 | <0.01 | 0.72 | 0.55–0.96 | 0.02 |

| South | 0.85 | 0.65–1.11 | 0.24 | 0.94 | 0.70–1.24 | 0.65 |

| West | 0.61 | 0.44–0.85 | <0.01 | 0.75 | 0.54–1.05 | 0.10 |

| Other | 0.76 | 0.59–0.97 | 0.03 | 0.81 | 0.63–1.04 | 0.09 |

Note: Multivariable Cox regression model was adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, liver disease etiology, modified Charlson score, and region.

Modified Charlson Index was calculated based on the original Charlson Comorbidity Score excluding weights for mild liver disease and severe liver disease.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study of CLD patients in the National COVID Cohort Collaborative, we found that only 15.8% of CLD patients were vaccinated. Nearly all (95%) of vaccinated patients received an mRNA vaccine as the initial dose and 82% were fully vaccinated. Given that CLD patients have been previously demonstrated to have lower immunological responses to various vaccinations, including to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccinations, there is a significant concern that CLD patients may be more susceptible to breakthrough infections and more severe outcomes than the overall population.4–8 A recent study using the N3C Data Enclave showed that the EIR for breakthrough infections in all fully vaccinated patients was ~5.0 per 1000 person‐months.19 In our study, we found that breakthrough infections occurred at a slightly higher rate for fully vaccinated CLD patients without cirrhosis (5.4 per 1000 person‐months) and at a similar rate for fully vaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis (4.9 per 1000 person‐months). Of note, breakthrough infections occurred at a much higher rate for CLD patients who had received additional or booster doses at an estimated rate of <8.6 per 1000 person‐months—these results, however, were limited by small numbers of events. For comparison, infection rates for unvaccinated patients were significantly higher (14.4 per 1000 person‐months for patients without cirrhosis and 12.6 per 1000 person‐months for those without cirrhosis)—though these figures are likely underestimates of the true rate attributable to our assignment of time zero as the first vaccination at each data site. Overall, the aggregate results suggest that CLD patients may not necessarily face a higher risk of breakthrough infections than the overall population. In multivariable IRR calculations (Table 3), presence of cirrhosis was not significantly associated with breakthrough infection. Whereas this finding was initially surprising, it is congruent with antibody response studies of patients with and without cirrhosis to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccinations, which showed that there were similar rates of neutralizing antibodies generated in CLD patients regardless of the presence of cirrhosis.7,8

Consistent with other studies in CLD patient populations, we found that receiving the mRNA‐1273 vaccine as the initial dose was associated with an 18% reduced risk for breakthrough infections compared with receiving the BNT162b2 vaccine.15,26 Moreover, we found a strong dose‐dependent relationship between the number of vaccine doses received and decreased risks of breakthrough infection among CLD patients, consistent with revised CDC guidance around additional and booster shots given the emergence of more transmissible and severe SARS‐CoV‐2 variants.27 Although patients may not always have a choice as to the type of vaccination they could receive, these data could help inform recommendations for those who do have a choice between different types of vaccinations.

Most important, among CLD patients with cirrhosis and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, vaccinated patients had lower rates of hospitalization, ventilation, and death within 30 days than unvaccinated patients. Although CLD patients with cirrhosis and breakthrough infection could still have serious complications, full vaccination was associated with a 66% reduction in all‐cause mortality within 30 days (aHR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.17–0.68). This figure is notably less than the 78% reduction in all‐cause mortality estimated from cohorts of veterans with CLD.15,16 Of particular note, partial vaccination was not statistically associated with a reduction in the risk of all‐cause mortality in our analyses. Given that the point estimate suggested partial protection as expected from previous studies, we suspect that this may have been attributable to low power. Moreover, consistent with analyses of the N3C Data Enclave from earlier in the pandemic, the 30‐day mortality rate for unvaccinated CLD patients with cirrhosis has remained at ~9%, despite new treatment regimens and therapeutics. These findings are likely attributable to the impact of SARS‐CoV‐2 variants, such as B.1.1.7 (Alpha) and B.1.617.2 (Delta),28–30 associated with more transmissible or severe disease.

Although this study is among the few on the impact of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccinations in a large, sex‐balanced, and diverse population of patients with CLD, there are several limitations that have been previously described in our works using the N3C Data Enclave. Limitations attributable to the use of N3C Data Enclave include overrepresentation of tertiary academic medical centers, selection bias attributable to derivation of SARS‐CoV‐2‐negative and ‐positive populations based on testing, systematic missingness of certain variables attributable to data heterogeneity, and likely misclassification between patients with AALD and NAFLD.9 These inherent limitations likely selected for a more clinically ill patient population than the general CLD and cirrhosis patient populations. Moreover, we were only able to determine associations with all‐cause mortality, rather than mortality attributable to COVID‐19, given that conclusive information regarding cause of death was not available in the N3C Data Enclave.

There are also several limitations specific to this particular study. First, the underlying vaccination data are based on recorded medication administrations and exposures at each of the data partner sites. These data may not include vaccinations administered at mass vaccination sites, local pharmacies, pop‐up vaccination sites, and other venues. Therefore, there may be a significant proportion of false negatives for detection of vaccine doses (patients who actually received a vaccination not recorded as such in the N3C Data Enclave). Considering this potential source of bias, the actual protection afforded by vaccines may be higher than what was reported. Second, although the N3C Data Enclave had additional or booster dose information in the recorded medication exposures at data partner sites, we were not able to estimate the mortality reduction associated with an additional or booster dose because of the low number of death events occurring in this population (<20).17 We therefore consolidated those who received three or more vaccine doses into the full vaccination category in our analyses for our second study question. Given that patients with cirrhosis are immunocompromised, full vaccination for this patient population may be more appropriately defined as three doses of the primary vaccination series per CDC guidance. The impact of additional or booster shots on CLD patients will be an active area of investigation for us as N3C accumulates and harmonizes additional vaccination data.

Finally, our use of the deidentified version of the N3C Data Enclave hindered our ability to differentiate the impact of various SARS‐CoV‐2 variants. To protect patient privacy, date shifting was uniformly applied within each data site. This means that our analyses could not investigate temporal trends. Based on the date on which we accessed the N3C Data Enclave (January 15, 2022) and our exclusion of patients whose date of SARS‐CoV‐2 testing was within 90 days of the calculated maximum data date for each site, our data likely reflect the B1.1.7 (Alpha) and B.1.617.2 (Delta) surges,29,30 but not the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) surge.28,31 The is a major limitation of our study and one that we hope to rectify in future analyses.

Despite this, our study is one of the largest studies of breakthrough infections and clinical outcomes in vaccinated CLD patients with and without cirrhosis. Though generally consistent with results from other studies, our findings showed that CLD patients may not experience breakthrough infections at a higher rate than the overall population and that receiving an initial dose of mRNA‐1273 vaccine may confer a marginally higher protection against breakthrough infections. In addition, we found that full vaccination was associated with a 66% risk reduction.

Although this and previous studies have demonstrated the significant advantages associated with vaccination, vaccine hesitancy remains common in multiple subsets of patients with cirrhosis.32 Given that they often serve as a “medical home” for this patient population, gastroenterologists, hepatologists, and other providers specializing in liver diseases should serve as key facilitators in increasing vaccination uptake.33,34 Potential strategies to increase vaccination include: (1) Emphasize the role of vaccination in decreasing the significant risk for hepatic decompensation and death associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.14 (2) Normalize hesitancy and work collaboratively with patients to correct mis‐ or false information regarding vaccines' safety, authorization process, or underlying technologies.35 (3) Strengthen partnerships with vaccination programs within/between health systems and community organizations to improve timely access to vaccines.14 (4) For patients who are also transplant candidates, highlight the need for vaccination before transplant because of deficient immune responses observed in the posttransplant setting.36 As the COVID‐19 pandemic continues to evolve with the emergence of new variants, vaccination (with potential variant‐specific boosters) will remain a cornerstone strategy to continue protecting patients with liver diseases.37,38

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Authorship was determined using ICMJE recommendations. Ge: Study concept and design; data extraction; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis. Digitale: Analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Pletcher: Acquisition of data; interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Lai: Study concept and design; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; obtained funding; study supervision.

N3C CONSORTIUM COLLABORATORS/AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Chute: Clinical data model expertise; data curation; data integration; data quality assurance; database/information system admin; funding acquisition; governance; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; N3C Phenotype definition; project evaluation; project management; regulatory oversight/admin. Harper: Clinical data model expertise; data quality assurance; governance. Gabriel: Clinical data model expertise; data integration. Haendel: Funding acquisition; governance; project management; regulatory oversight/admin. Pfaff: Clinical data model expertise; data quality assurance; data integration; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Leese: Clinical data model expertise; data quality assurance; data integration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The analyses described in this publication were conducted with data or tools accessed through the NCATS N3C Data Enclave covid.cd2h.org/enclave and supported by NCATS U24 TR002306. This research was possible because of the patients whose information is included within the data from participating organizations (covid.cd2h.org/dtas) and the organizations and scientists (covid.cd2h.org/duas) who have contributed to the ongoing development of this community resource.17 The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the N3C program. The N3C data transfer to NCATS is performed under a Johns Hopkins University Reliance Protocol (#IRB00249128) or individual site agreements with the NIH. The N3C Data Enclave is managed under the authority of the NIH; information can be found at: https://ncats.nih.gov/n3c/resources. We gratefully acknowledge the following core contributors to N3C: Adam B. Wilcox, Adam M. Lee, Alexis Graves, Alfred (Jerrod) Anzalone, Amin Manna, Amit Saha, Amy Olex, Andrea Zhou, Andrew E. Williams, Andrew Southerland, Andrew T. Girvin, Anita Walden, Anjali A. Sharathkumar, Benjamin Amor, Benjamin Bates, Brian Hendricks, Brijesh Patel, Caleb Alexander, Carolyn Bramante, Cavin Ward‐Caviness, Charisse Madlock‐Brown, Christine Suver, Christopher Chute, Christopher Dillon, Chunlei Wu, Clare Schmitt, Cliff Takemoto, Dan Housman, Davera Gabriel, David A. Eichmann, Diego Mazzotti, Don Brown, Eilis Boudreau, Elaine Hill, Elizabeth Zampino, Emily Carlson Marti, Emily R. Pfaff, Evan French, Farrukh M. Koraishy, Federico Mariona, Fred Prior, George Sokos, Greg Martin, Harold Lehmann, Heidi Spratt, Hemalkumar Mehta, Hongfang Liu, Hythem Sidky, J.W. Awori Hayanga, Jami Pincavitch, Jaylyn Clark, Jeremy Richard Harper, Jessica Islam, Jin Ge, Joel Gagnier, Joel H. Saltz, Joel Saltz, Johanna Loomba, John Buse, Jomol Mathew, Joni L. Rutter, Julie A. McMurry, Justin Guinney, Justin Starren, Karen Crowley, Katie Rebecca Bradwell, Kellie M. Walters, Ken Wilkins, Kenneth R. Gersing, Kenrick Dwain Cato, Kimberly Murray, Kristin Kostka, Lavance Northington, Lee Allan Pyles, Leonie Misquitta, Lesley Cottrell, Lili Portilla, Mariam Deacy, Mark M. Bissell, Marshall Clark, Mary Emmett, Mary Morrison Saltz, Matvey B. Palchuk, Melissa A. Haendel, Meredith Adams, Meredith Temple‐O'Connor, Michael G. Kurilla, Michele Morris, Nabeel Qureshi, Nasia Safdar, Nicole Garbarini, Noha Sharafeldin, Ofer Sadan, Patricia A. Francis, Penny Wung Burgoon, Peter Robinson, Philip R.O. Payne, Rafael Fuentes, Randeep Jawa, Rebecca Erwin‐Cohen, Rena Patel, Richard A. Moffitt, Richard L. Zhu, Rishi Kamaleswaran, Robert Hurley, Robert T. Miller, Saiju Pyarajan, Sam G. Michael, Samuel Bozzette, Sandeep Mallipattu, Satyanarayana Vedula, Scott Chapman, Shawn T. O'Neil, Soko Setoguchi, Stephanie S. Hong, Steve Johnson, Tellen D. Bennett, Tiffany Callahan, Umit Topaloglu, Usman Sheikh, Valery Gordon, Vignesh Subbian, Warren A. Kibbe, Wenndy Hernandez, Will Beasley, Will Cooper, William Hillegass, and Xiaohan Tanner Zhang. Details of contributions are available at: covid.cd2h.org/core‐contributors.

DATA PARTNERS WITH RELEASED DATA

The following institutions whose data are released or pending: Available: Advocate Health Care Network—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM); Boston University Medical Campus—UL1TR001430: Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute; Brown University—U54GM115677: Advance Clinical Translational Research (Advance‐CTR); Carilion Clinic—UL1TR003015: iTHRIV Integrated Translational health Research Institute of Virginia; Charleston Area Medical Center—U54GM104942: West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute (WVCTSI); Children's Hospital Colorado—UL1TR002535: Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute; Columbia University Irving Medical Center—UL1TR001873: Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research; Duke University—UL1TR002553: Duke Clinical and Translational Science Institute; George Washington Children's Research Institute—UL1TR001876: Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children's National (CTSA‐CN); George Washington University—UL1TR001876: Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children's National (CTSA‐CN); Indiana University School of Medicine—UL1TR002529: Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute; Johns Hopkins University—UL1TR003098: Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research; Loyola Medicine—Loyola University Medical Center; Loyola University Medical Center—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM); Maine Medical Center—U54GM115516: Northern New England Clinical and Translational Research (NNE‐CTR) Network; Massachusetts General Brigham—UL1TR002541: Harvard Catalyst; Mayo Clinic Rochester—UL1TR002377: Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCaTS); Medical University of South Carolina—UL1TR001450: South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute (SCTR); Montefiore Medical Center—UL1TR002556: Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Einstein and Montefiore; Nemours—U54GM104941: Delaware CTR ACCEL Program; NorthShore University HealthSystem—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM); Northwestern University at Chicago—UL1TR001422: Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NUCATS); OCHIN—INV‐018455: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation grant to Sage Bionetworks; Oregon Health & Science University—UL1TR002369: Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute; Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center—UL1TR002014: Penn State Clinical and Translational Science Institute; Rush University Medical Center—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM); Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey—UL1TR003017: New Jersey Alliance for Clinical and Translational Science; Stony Brook University—U24TR002306; The Ohio State University—UL1TR002733: Center for Clinical and Translational Science; The State University of New York at Buffalo—UL1TR001412: Clinical and Translational Science Institute; The University of Chicago—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM); The University of Iowa—UL1TR002537: Institute for Clinical and Translational Science; The University of Miami Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine—UL1TR002736: University of Miami Clinical and Translational Science Institute; The University of Michigan at Ann Arbor—UL1TR002240: Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research; The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston—UL1TR003167: Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences (CCTS); The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston—UL1TR001439: The Institute for Translational Sciences; The University of Utah—UL1TR002538: Uhealth Center for Clinical and Translational Science; Tufts Medical Center—UL1TR002544: Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute; Tulane University—UL1TR003096: Center for Clinical and Translational Science; University Medical Center New Orleans—U54GM104940: Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science (LA CaTS) Center; University of Alabama at Birmingham—UL1TR003096: Center for Clinical and Translational Science; University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences—UL1TR003107: UAMS Translational Research Institute; University of Cincinnati—UL1TR001425: Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training; University of Colorado Denver, Anschutz Medical Campus—UL1TR002535: Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute; University of Illinois at Chicago—UL1TR002003: UIC Center for Clinical and Translational Science; University of Kansas Medical Center—UL1TR002366: Frontiers: University of Kansas Clinical and Translational Science Institute; University of Kentucky—UL1TR001998: UK Center for Clinical and Translational Science; University of Massachusetts Medical School Worcester—UL1TR001453: The UMass Center for Clinical and Translational Science (UMCCTS); University of Minnesota—UL1TR002494: Clinical and Translational Science Institute; University of Mississippi Medical Center—U54GM115428: Mississippi Center for Clinical and Translational Research (CCTR); University of Nebraska Medical Center—U54GM115458: Great Plains IDeA‐Clinical & Translational Research; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—UL1TR002489: North Carolina Translational and Clinical Science Institute; University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center—U54GM104938: Oklahoma Clinical and Translational Science Institute (OCTSI); University of Rochester—UL1TR002001: UR Clinical & Translational Science Institute; University of Southern California—UL1TR001855: The Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute (SC CTSI); University of Vermont—U54GM115516: Northern New England Clinical & Translational Research (NNE‐CTR) Network; University of Virginia—UL1TR003015: iTHRIV Integrated Translational health Research Institute of Virginia; University of Washington—UL1TR002319: Institute of Translational Health Sciences; University of Wisconsin–Madison—UL1TR002373: UW Institute for Clinical and Translational Research; Vanderbilt University Medical Center—UL1TR002243: Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research; Virginia Commonwealth University—UL1TR002649: C. Kenneth and Dianne Wright Center for Clinical and Translational Research; Wake Forest University Health Sciences—UL1TR001420: Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute; Washington University in St. Louis—UL1TR002345: Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences; Weill Medical College of Cornell University—UL1TR002384: Weill Cornell Medicine Clinical and Translational Science Center; West Virginia University—U54GM104942: West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute (WVCTSI). Submitted: Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai—UL1TR001433: ConduITS Institute for Translational Sciences; The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler—UL1TR003167: Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences (CCTS); University of California–Davis—UL1TR001860: UCDavis Health Clinical and Translational Science Center; University of California–Irvine—UL1TR001414: The UC Irvine Institute for Clinical and Translational Science (ICTS); University of California–Los Angeles—UL1TR001881: UCLA Clinical Translational Science Institute; University of California–San Diego—UL1TR001442: Altman Clinical and Translational Research Institute; University of California–San Francisco—UL1TR001872: UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Pending: Arkansas Children's Hospital—UL1TR003107: UAMS Translational Research Institute; Baylor College of Medicine—None (Voluntary); Children's Hospital of Philadelphia—UL1TR001878: Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics; Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center—UL1TR001425: Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training; Emory University—UL1TR002378: Georgia Clinical and Translational Science Alliance; HonorHealth—None (Voluntary); Loyola University Chicago—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM); Medical College of Wisconsin—UL1TR001436: Clinical and Translational Science Institute of Southeast Wisconsin; MedStar Health Research Institute—UL1TR001409: The Georgetown–Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science (GHUCCTS); MetroHealth—None (Voluntary); Montana State University—U54GM115371: American Indian/Alaska Native CTR; NYU Langone Medical Center—UL1TR001445: Langone Health's Clinical and Translational Science Institute; Ochsner Medical Center—U54GM104940: Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science (LA CaTS) Center; Regenstrief Institute—UL1TR002529: Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute; Sanford Research—None (Voluntary); Stanford University—UL1TR003142: Spectrum: The Stanford Center for Clinical and Translational Research and Education; The Rockefeller University—UL1TR001866: Center for Clinical and Translational Science; The Scripps Research Institute—UL1TR002550: Scripps Research Translational Institute; University of Florida—UL1TR001427: UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute; University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center—UL1TR001449: University of New Mexico Clinical and Translational Science Center; University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio—UL1TR002645: Institute for Integration of Medicine and Science; Yale New Haven Hospital—UL1TR001863: Yale Center for Clinical Investigation.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors of this study were supported by KL2TR001870 (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Ge), AASLD Anna S. Lok Advanced/Transplant Hepatology Award (AASLD Foundation, Ge), P30DK026743 (UCSF Liver Center Grant, Ge and Lai), F31HL156498 (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Digitale), UL1TR001872 (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Pletcher), and R01AG059183 (National Institute on Aging, Lai). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or any other funding agencies. The funding agencies played no role in the analysis of the data or the preparation of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Jin Ge received grants from Merck.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The N3C Data Enclave (covid.cd2h.org/enclave) houses fully reproducible, transparent, and broadly available limited and deidentified data sets (HIPAA definitions: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for‐professionals/privacy/specialtopics/de‐identification/index.html). Data are accessible by investigators at institutions that have signed a Data Use Agreement with the NIH who have taken human subjects and security training and attest to the N3C User Code of Conduct. Investigators wishing to access the limited data set must also supply an institutional IRB protocol. All requests for data access are reviewed by the NIH Data Access Committee. A full description of the N3C Enclave governance has been published; information about how to apply for access is available on the NCATS website: https://ncats.nih.gov/n3c/about/applying‐for‐access. Reviewers and health authorities will be given access permission and guidance to aid reproducibility and outcomes assessment. A Frequently Asked Questions section about the data and access has been created at: https://ncats.nih.gov/n3c/about/program‐faq. The data model is OMOP 5.3.1; specifications are posted at: https://ncats.nih.gov/files/OMOP_CDM_COVID.pdf.

PREPRINT INFORMATION

This article is available on the medRxiv preprint server as MEDRXIV/2022/271490 at: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.25.22271490.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AALD, alcohol‐associated liver disease; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CLD, chronic liver disease; EIR, estimated incidence rate; EHR, electronic health record; INR, international normalized ratio; IQR, interquartile range; IRs, incidence rates; IRB, institutional review board; IRR, incidence rate ratio; MELD‐Na, Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease‐Sodium; N3C, National COVID Cohort Collaborative; NCATS, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; NIH, National Institutes of Health; OMOP, Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2;

Funding information American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Grant/Award Number: Anna S. Lok Advanced/ Transplant Hepatology Award; Liver Center, University of California, San Francisco, Grant/Award Number: P30DK026743; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant/ Award Number: KL2TR001870 and UL1TR001872; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Grant/Award Number: F31HL156498; National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: R01AG059183

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.hepjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Jin Ge, Email: jin.ge@ucsf.edu.

Collaborators: Christopher G. Chute, Jeremy R. Harper, Davera Gabriel, Melissa A. Haendel, Emily Pfaff, and Peter Leese

REFERENCES

- 1. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, Cárdenas V, Shukarev G, Grinsztejn B, et al. Safety and efficacy of single‐dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against COVID‐19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2187–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. El Sahly HM, Baden LR, Essink B, Doblecki‐Lewis S, Martin JM, Anderson EJ, et al. Efficacy of the mRNA‐1273 SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine at completion of blinded phase. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1774–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCashland TM, Preheim LC, Gentry MJ. Pneumococcal vaccine response in cirrhosis and liver transplantation. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:757–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Härmälä S, Parisinos CA, Shallcross L, O'Brien A, Hayward A. Effectiveness of influenza vaccines in adults with chronic liver disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aggeletopoulou I, Davoulou P, Konstantakis C, Thomopoulos K, Triantos C. Response to hepatitis B vaccination in patients with liver cirrhosis. Rev Med Virol. 2017;27(6). 10.1002/rmv.1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thuluvath PJ, Robarts P, Chauhan M. Analysis of antibody responses after COVID‐19 vaccination in liver transplant recipients and those with chronic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2021;75:1434–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ai J, Wang J, Liu D, Xiang H, Guo Y, Lv J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines in patients with chronic liver diseases (CHESS‐NMCID 2101): a multicenter study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:1516–24.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ge J, Pletcher MJ, Lai JC, N3C Consortium. Outcomes of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in patients with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis: a national COVID cohort collaborative study. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1487–501.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ioannou GN, Liang PS, Locke E, Green P, Berry K, O'Hare AM, et al. Cirrhosis and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in US Veterans: risk of infection, hospitalization, ventilation and mortality. Hepatology. 2020;74:322–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iavarone M, D'Ambrosio R, Soria A, Triolo M, Pugliese N, Del Poggio P, et al. High rates of 30‐day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and COVID‐19. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1063–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marjot T, Moon AM, Cook JA, Abd‐Elsalam S, Aloman C, Armstrong MJ, et al. Outcomes following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in patients with chronic liver disease: an international registry study. J Hepatol. 2021;74:567–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bajaj JS, Garcia‐Tsao G, Biggins SW, Kamath PS, Wong F, McGeorge S, et al. Comparison of mortality risk in patients with cirrhosis and COVID‐19 compared with patients with cirrhosis alone and COVID‐19 alone: multicentre matched cohort. Gut. 2021;70:531–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fix OK, Blumberg EA, Chang KM, Chu J, Chung RT, Goacher EK, et al. American association for the study of liver diseases expert panel consensus statement: vaccines to prevent coronavirus disease 2019 infection in patients with liver disease. Hepatology. 2021;74:1049–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. John BV, Deng Y, Scheinberg A, Mahmud N, Taddei TH, Kaplan D, et al. Association of BNT162b2 mRNA and mRNA‐1273 vaccines with COVID‐19 infection and hospitalization among patients with cirrhosis. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:1306–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. John BV, Deng Y, Schwartz KB, Taddei TH, Kaplan DE, Martin P, et al. Postvaccination COVID‐19 infection is associated with reduced mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2022;76:126–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haendel MA, Chute CG, Bennett TD, Eichmann DA, Guinney J, Kibbe WA, et al. The National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C): rationale, design, infrastructure, and deployment. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28:427–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bennett TD, Moffitt RA, Hajagos JG, Amor B, Anand A, Bissell MM, et al. Clinical characterization and prediction of clinical severity of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection among US adults using data from the US National COVID cohort collaborative. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2116901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sun J, Zheng Q, Madhira V, Olex AL, Anzalone AJ, Vinson A, et al. Association between immune dysfunction and COVID‐19 breakthrough infection after SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:153–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National COVID Cohort Collaborative [Internet]. [cited 2021. Apr 8]. Available from: https://covid.cd2h.org

- 21. OMOP Common Data Model—OHDSI [Internet]. [cited 2021. Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.ohdsi.org/data‐standardization/the‐common‐data‐model/

- 22. Stay Up to Date with Your Vaccines | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2022. Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/vaccines/stay‐up‐to‐date.html

- 23. NREVSS | RSV Regional Trends | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2021. Apr 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/surveillance/nrevss/rsv/region.html

- 24. Frome EL, Checkoway H. Epidemiologic programs for computers and calculators. Use of Poisson regression models in estimating incidence rates and ratios. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:309–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cox DR. Regression models and life‐tables. J R Stat Soc B Methodol. 1972;34:187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dickerman BA, Gerlovin H, Madenci AL, Kurgansky KE, Ferolito BR, Figueroa Muñiz MJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA‐1273 vaccines in U.S. Veterans. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:105–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. COVID‐19 Vaccine Booster Shots | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2022. Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/vaccines/booster‐shot.html?s_cid=11706:cdc%20covid%20booster%20shot%20guidelines:sem.ga:p:RG:GM:gen:PTN:FY22

- 28. Variants and Genomic Surveillance for SARS‐CoV‐2 | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2022. Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/variants/variant‐surveillance.html

- 29. Davies NG, Abbott S, Barnard RC, Jarvis CI, Kucharski AJ, Munday JD, et al. Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS‐CoV‐2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Science. 2021;372:eabg3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Simmons R, Thelwall S, et al. Effectiveness of covid‐19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:585–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Update on Omicron [Internet]. [cited 2022. Jan 24]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/28‐11‐2021‐update‐on‐omicron

- 32. Mahmud N, Chapin SE, Kaplan DE, Serper M. Identifying patients at highest risk of remaining unvaccinated against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in a large veterans health administration cohort. Liver Transpl. 2021;27:1665–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mellinger JL, Volk ML. Multidisciplinary management of patients with cirrhosis: a need for care coordination. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:217–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meier SK, Shah ND, Talwalkar JA. Adapting the patient‐centered specialty practice model for populations with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:492–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moss P, Berenbaum F, Curigliano G, Grupper A, Berg T, Pather S. Benefit‐risk evaluation of COVID‐19 vaccination in special population groups of interest. Vaccine. 2022;40:4348–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boyarsky BJ, Werbel WA, Avery RK, Tobian AAR, Massie AB, Segev DL, et al. Antibody response to 2‐dose SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccine series in solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA. 2021;325:2204–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pfizer and BioNTech Announce Omicron‐Adapted COVID‐19 Vaccine Candidates Demonstrate High Immune Response Against Omicron | Pfizer [Internet]. 2022 Jun [cited 2022. Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press‐release/press‐release‐detail/pfizer‐and‐biontech‐announce‐omicron‐adapted‐covid‐19

- 38. Moderna Announces Omicron‐Containing Bivalent Booster Candidate mRNA‐1273.214 Demonstrates Superior Antibody Response Against Omicron| Moderna [Internet]. 2022. Jun [cited 2022 Jul 7]. Available from: https://investors.modernatx.com/news/news‐details/2022/Moderna‐Announces‐Omicron‐Containing‐Bivalent‐Booster‐Candidate‐mRNA‐1273.214‐Demonstrates‐Superior‐Antibody‐Response‐Against‐Omicron/default.aspx

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The N3C Data Enclave (covid.cd2h.org/enclave) houses fully reproducible, transparent, and broadly available limited and deidentified data sets (HIPAA definitions: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for‐professionals/privacy/specialtopics/de‐identification/index.html). Data are accessible by investigators at institutions that have signed a Data Use Agreement with the NIH who have taken human subjects and security training and attest to the N3C User Code of Conduct. Investigators wishing to access the limited data set must also supply an institutional IRB protocol. All requests for data access are reviewed by the NIH Data Access Committee. A full description of the N3C Enclave governance has been published; information about how to apply for access is available on the NCATS website: https://ncats.nih.gov/n3c/about/applying‐for‐access. Reviewers and health authorities will be given access permission and guidance to aid reproducibility and outcomes assessment. A Frequently Asked Questions section about the data and access has been created at: https://ncats.nih.gov/n3c/about/program‐faq. The data model is OMOP 5.3.1; specifications are posted at: https://ncats.nih.gov/files/OMOP_CDM_COVID.pdf.