Abstract

Objective

There is a growing body of literature suggesting the novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID‐19) negatively impacts mental health in individuals self‐reporting an eating disorder (ED); however, limited pediatric data is available about the impact COVID‐19 has had on youth with EDs, specifically Anorexia Nervosa (AN). Our study uses a cross‐sectional design to explore differences in ED symptoms between adolescents diagnosed with AN during the COVID‐19 pandemic compared to a retrospective cohort of adolescents for whom these measures were previously collected, prior to the pandemic.

Method

We report cross‐sectional data assessing differences between AN behaviors and cognitions during the COVID‐19 pandemic compared to a retrospective cohort (n = 25 per cohort) assessed before the pandemic.

Results

Results suggest that individuals with a first‐time diagnosis of AN during the pandemic had lower percent expected body weight, and more compulsive exercise behaviors.

Conclusions

These data support existing pediatric findings in exercise and body weight differences in adolescents with AN before and during the pandemic. Findings may be helpful in informing considerations for providers treating ED patients amidst and after the pandemic.

Public Significance

This manuscript compares a retrospective cohort of adolescents diagnosed with AN prior to the pandemic to a cohort of adolescents diagnosed with AN during the pandemic. Results report that adolescents diagnosed with AN during the pandemic have lower weights and increased compensatory exercise behavior compared to adolescents diagnosed with AN before the pandemic despite no difference in length of illness. Findings may be helpful in informing considerations for providers treating ED patients amidst and after the pandemic.

Keywords: adolescent, anorexia nervosa, COVID‐19, exercise, pandemic

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the initial declaration of the global SARS CoV‐2 Virus (COVID‐19) pandemic on March 1, 2020, there have been significant disruptions to general health, economic status, social activities, and future oriented planning. These have inevitably impacted mental health across adolescent and adult samples, necessitating research efforts to pinpoint urgent interventions. For example, prior research has found that 61% of youth in Ontario (ages 12–25) report general worsening of their mental health during the pandemic (Radomski et al., 2022). One particularly vulnerable group of youth at risk for the harmful effects of the pandemic is adolescents with eating disorders (EDs) such as Anorexia Nervosa (AN). AN is an ED diagnosis characterized by low body weight, behaviors driving weight loss or weight suppression (e.g., caloric restriction), and body image disturbance (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The lifetime prevalence of AN in adolescent females is approximately 0.48%–1.7% (Hoek & van Hoeken, 2003; Lucas et al., 1991; Pinhas et al., 2011).

Studies have found that approximately 50% of youth with EDs report an increase or resurgence of ED symptomology (such as dietary restriction, fear of weight gain, or compensatory behaviors) during the pandemic (Graell et al., 2020). Furthermore, Mathews and colleagues (Matthews et al., 2021) found that youth hospitalized during the COVID‐19 pandemic were over eight times more likely to be readmitted within 30 days of discharge relative to patients hospitalized before the pandemic. Additionally, one third of patients in their study cited the pandemic consequences, such as concerns for weight gain as a result of sports cancellations and fears of gaining the “Quarantine‐15,” as a primary correlate of their AN onset.

Since the pandemic's onset, recent research has cumulatively reported greater medical stabilization hospitalizations for AN across development and an increase in incidence of new AN diagnoses (Agostino et al., 2021; Goldberg et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2021; Otto et al., 2021). Relatedly, Toulany and colleagues report an increase in acute care visits for EDs throughout the first 10 months of COVID‐19 (Toulany et al., 2022). A recent systematic review conducted for individuals with EDs (mean age of 24 years across all studies) reports an overarching increase in pediatric (83%) and adult (16%) hospital admissions for EDs during the pandemic, worsening of ED symptoms in most studies following the pandemic onset, and worsening mental health symptoms, such as anxiety and depression (Devoe et al., 2022). Taken together, these studies point to the dire impact of the pandemic on AN prevalence and severity in both adolescents and adults.

Of note, only 10 of the 53 studies included in the prior review were of pediatric populations. Within the pediatric studies, authors report a general trend wherein the impact of the pandemic on mental health appears to be more severe in young people, potentially contributing to the greater number of pediatric ED hospital admissions seen during the pandemic timeframe. One additional pediatric ED study not included in the aforementioned review is a cohort study using retrospective chart review to compare ED symptoms of adolescents presenting for assessment since the COVID‐19 pandemic to a retrospective cohort of those who presented 1 year prior (Spettigue et al., 2021). Consistent with the prior findings at large, they found that the pandemic cohort were more medically unstable and required hospitalization more often compared to the retrospective cohort.

The current report seeks to add to this limited body of research in pediatric EDs using a cross‐sectional design to explore the impact of COVID‐19 on the emergence of ED symptoms compared to a retrospective cohort of adolescents for whom measures of eating psychopathology, mood, and exercise behaviors were previously collected. We hope to replicate and expand on the data presented by Spettigue et al. (2021) by comparing two cohorts before and after the pandemic, and providing data on exercise behaviors in addition to ED cognitions and mood differences. Based on prior literature at large, we predicted that adolescents who developed AN during the pandemic would report poorer ED cognitions, greater anxiety, depression, and compulsive exercise behaviors, and have lower weights compared to youth who presented with AN onset prior to the start of the pandemic.

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants

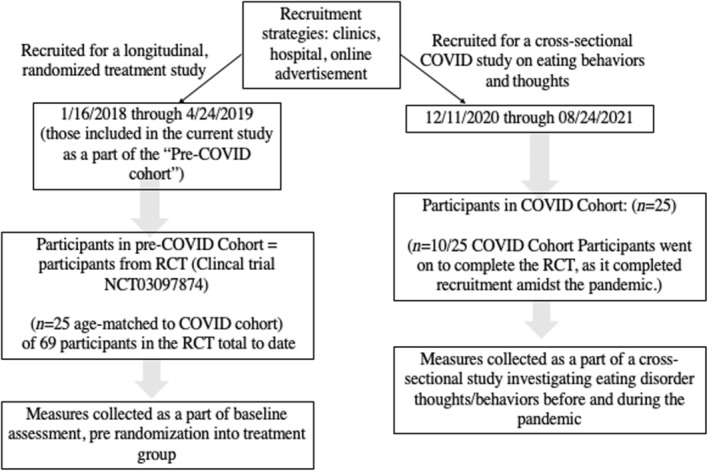

This exploratory study was conducted in a university clinic and approved by the Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent and/or assent. Participants belonged to two cohorts: half the participants (from a retrospective cohort, clinical trial registration number: NCT03097874) participated in a prior study (L'Insalata et al., 2020) before the pandemic and were age‐matched with 25 treatment seeking adolescents who developed AN during the COVID‐19 pandemic (recruited from December 11, 2020 through August 24, 2021) (Figure 1). All data reported in the current manuscript were collected at a pre‐treatment timepoint. The 25 age‐matched participants from the retrospective cohort were recruited from January 16, 2018 through April 24, 2019. For all participants in the COVID‐19 cohort, this study was advertised as a one‐time study examining differences in ED thoughts and behaviors before and after the pandemic. Recruitment strategies did not differ by cohort, as participants in both cohorts were recruited through clinics, hospitals, and online advertisements. There were no exclusion criteria based on severity of illness. Inclusion criteria were the same across both cohorts, and they were: being 12–18 years of age with a diagnosis of AN (including AN‐R and AN‐BP), ability to read/speak English, and expected mean body weight percentage (%EBW) <88.0%. In both groups, diagnoses were made by a licensed clinician to verify eligibility. No participants in either group met criteria for AN‐B/P, though this was not an exclusionary criterion.

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment flow chart

2.2. Study procedures

After consent, demographic variables (Table 1) were collected, and the following semi‐structured interviews and self‐report measures were administered by trained assessors.

Eating disorder examination (EDE) (Fairburn et al., 2008) is a standardized semi‐structured interview that measures the severity of the characteristic psychopathology of EDs and is comprised of four distinct subscales (Restraint [5 items], Eating Concern [5 items], Shape Concern [8 items], and Weight Concern [5 items]) that average to compute a global scale. Internal consistency across the global score was acceptable to excellent (α's = 0.74–0.91) in this study.

EBW was calculated using a computer program based on the Center for Disease Control Growth Charts with weight adjusted for age, sex, and height. This formula for calculating percent EBW has been used in previous RCTs, including the study from which the retrospective cohort was drawn (Le Grange et al., 2012; L'Insalata et al., 2020). Weight was reported either by parents using an at‐home scale or from recent doctor appointments for both cohorts.

Compulsive exercise test (CET) (Meyer et al., 2016): This is a 24‐item multidimensional measure assessing core factors contributing to excessive exercise behaviors, specifically among patients with EDs. Internal consistency within the current sample was high for this measure (α = 0.90).

Commitment to exercise scales (Davis et al., 1993): This 8‐item measure is similar to the CET, evaluating the degree of psychological commitment and corresponding attitudinal and behavioral features of exercise. Internal consistency within the current sample was high for this measure (α = 0.88).

Beck Depression Inventory‐II (BDI‐II) (Beck et al., 1996). This is a 21‐item scale widely used to assess depression symptoms. In this study, the BDI‐II demonstrated good internal consistency reliability (α = 0.90).

Beck anxiety inventory (BAI) (Beck & Steer, 1993): This is a 21‐item well‐validated scale designed to assess symptoms of anxiety over the past month. The BAI demonstrated good internal consistency reliability (α = 0.94) in the current study.

TABLE 1.

Sample demographic and clinical characteristics

| Adolescent | Retrospective cohort (N = 25) mean (SD) or n (%) | COVID‐19 cohort (N = 25) mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent age (in years) | 15.08 (1.71) | 15.08 (1.71) |

| Adolescent sex a | ||

| Female | 24 (96%) | 24 (96%) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 1 (4%) | |

| Adolescent gender | ||

| Female | 24 (96%) | 24 (96%) |

| Male | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| Adolescent race b , c | ||

| Caucasian | 13 (54.17%) | 16 (66.67%) |

| Asian | 8 (33.3%) | 5 (20.83%) |

| Multi‐racial | 3 (12.5%) | 2 (8.33%) |

| Prefer not to disclose | N/A | 1 (4.17%) |

| Adolescent ethnicity b | ||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 3 (12%) | 2 (8.33%) |

| Non‐Hispanic/Non‐Latinx | 22 (88%) | 22 (91.67%) |

| Hospitalizations (range) | [0–1] | [0–4] |

| AN duration (in months) | 6.84 (3.67) | 7.72 (3.91) |

| EDE global score | 2.66 (1.55) | 3.09 (1.39) |

| %EBW | 83.81 (4.96) | 78.95 (8.94) |

Note: %EBW is percent expected body weight based on normative data for age, sex, height, and current weight.

Abbreviations: %EBW, expected mean body weight percentage; EDE, eating disorder examination; NOS, not otherwise specified; SD, standard deviation.

Adolescent sex for one participant in the retrospective cohort was missing and is therefore not reported.

Certain participant demographics are missing due to changes in National Institute of Health race and ethnicity reporting standards over time.

Adolescent race (%) was calculated out of n = 24 for both the pre‐COVID‐19 and post‐COVID‐19 sample.

2.3. Statistical approach

We conducted exploratory, descriptive analyses to examine between group effects. Considering the exploratory nature of this study and small sample size, we report effect size estimates (ES) for interpretation (Hc, 2014; Kraemer, 2019; Kraemer et al., 2020). Analyses were completed using SPSS Version 27. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

3. RESULTS

An independent samples t test was conducted to compare the effect of the pandemic on clinical variables relating to ED symptoms, including weight (%EBW), eating disorder cognitions (as measured by the EDE Global score), exercise behavior (CES and CET), anxiety (BAI), and depression (BDI) in the COVID‐19 cohort compared to the retrospective cohort, for whom these measures were collected prior to the pandemic. Individuals in the COVID‐19 cohort reported greater exercise commitment (M = 2.70, SD = 0.63 vs. M = 2.25, SD = 0.62), more compulsive exercise behaviors (M = 3.05, SD = 0.72 vs. M = 2.51, SD = 0.70), and lower weights, or %EBW (M = 78.94%, SD = 8.94% vs. M = 83.81%, SD = 4.96%), relative to the retrospective cohort (Table 2). These differences were accompanied by medium‐large effect sizes. Differences between EDEs, depression, and anxiety scores between groups were accompanied by negligible‐small effect sizes. Of note, demographic variables of age and duration of illness did not differ significantly between groups.

TABLE 2.

Between‐subjects' differences on continuous outcome measures

| Between subjects | Retrospective cohort (N = 25) | 95% CI | COVID‐19 cohort (N = 25) | 95% CI | t | Cohen's d [95%CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI M (SD) | 17.80 (10.00) | 13.67–21.93 | 21.12 (10.97) | 16.59–22.45 | −1.12 | −0.32 [−0.87 to 0.24] |

| BAI M (SD) | 18.30 (14.19) | 12.16–24.44 | 18.41 (12.49) | 13.14–23.69 | −0.03 | −0.01 [−0.58 to 0.56] |

| CES M (SD) | 2.25 (0.62) | 1.99–2.51 | 2.70 (0.63) | 2.40–2.92 | −2.32 | −0.70 [−1.22 to −0.08] a |

| CET M (SD) | 2.51 (0.70) | 2.20–1.81 | 3.05 (0.72) | 2.75–3.34 | −2.56 | −0.75 [−1.34 to −0.15] a |

| EDE global M (SD) | 2.66 (1.54) | 2.02–3.29 | 3.09 (1.39) | 2.52–3.66 | −1.04 | −0.29 [−0.85 to 0.27] |

| EBW% M (SD) | 83.81 (4.96) | 81.61–86.01 | 78.94 (8.94) | 75.24–82.64 | 2.26 | 0.66 [0.07–1.25] a |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

Here, Cohen's d = 0.2, 0.5, 0.8 can be interpreted as small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively.

4. DISCUSSION

Adolescents who developed AN during the pandemic on average appear to be lower weight and engaging in more rigid, compensatory exercise behavior; these differences were accompanied by medium‐large effect sizes, which must be considered in line with the exploratory nature of this study. Self‐reported ED cognitions, anxiety, and depression in the COVID‐19 cohort were comparable to the retrospective cohort, which was not aligned with our original hypotheses. From a physiological perspective, the COVID‐19 cohort had lower %EBWs, consistent with prior research (Matthews et al., 2021; Spettigue et al., 2021). It is possible that for some adolescents, engagement in compulsive exercise behaviors function to cope with feelings of anxiety and depression and ED cognitions in a time of uncertainty and stress (De Candia et al., 2021), which may contribute to similar mood and cognition scores between cohorts. However, without a larger, well‐powered study to conduct multivariate analyses, this reminds purely speculative.

Indeed, prior research has consistently found increased hospitalizations for EDs during the pandemic period, particularly for pediatric populations (Agostino et al., 2021; Goldberg et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2021; Otto et al., 2021). While the results in the current manuscript are exploratory in nature, they provide preliminary data around how exercise behavior appears to differ between a cohort of individuals diagnosed with AN before the pandemic, and a cohort diagnosed with AN amid the pandemic, replicating similar findings reported in a retrospective chart review conducted by Spettigue et al. (2021). This study adds preliminary data to this burgeoning area of research, finding that that adolescents who developed AN during the pandemic reported greater engagement in harmful exercise behaviors and a greater commitment to exercise in lieu of alternative activities, which may be a maladaptive solution to avoid previously reported pandemic consequences (e.g., not wanting to gain the “Quarantine‐15”) (Matthews et al., 2021). Our COVID‐19 sample also had lower %EBW than the retrospective cohort, consistent with some prior research (Toulany et al., 2022). This may be attributable to engagement in harmful exercise behavior and potential hesitation of parents taking their child to be assessed for an ED during the early weeks of the pandemic, leading to a more acute onset of the ED. However, these speculations require larger, well‐powered studies to comprehensively examine the cause of differences in %EBW. Ultimately, the data presented in this manuscript largely replicate prior research reporting physiological and behavioral differences in those diagnosed with an ED during the COVID‐19 pandemic on individuals with EDs across development.

Strengths of this exploratory study include the use of a semi‐structured interview (EDE) in conjunction with self‐report data on mood and exercise behavior to compare two cohorts of adolescents with AN before and amidst the pandemic. However, this study should also be considered in light of several limitations. The small sample reported in this manuscript limits significance testing and is intended to be exploratory in design. An additional limitation includes absence of participants' individual growth trajectory to inform EBW estimates. EBW estimations based on population means may thereby differ, possibly impacting the extent of weight suppression seen by group. Moreover, it is possible that the two samples compared may have differences in ways not measured by the current study. The pre‐COVID sample were beginning a treatment study (though all measures included in this manuscript were collected prior to treatment or randomization), whereas the COVID‐19 sample were engaging in a one‐time cross‐sectional study. Recruitment for both samples, however, occurred at the same centers with treatment‐seeking patients in an effort to minimize differences between groups. An additional limitation includes the representativeness of the COVID‐19 cohort to the general AN population. While it is reassuring that duration of illness did not differ between groups, given the small sample size, it is possible that observed differences may be attributable to variables other than the impact of the pandemic. Lastly, no patients identified as African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, which may limit generalizability of findings to these minority groups. Future studies may consider novel recruitment strategies outlined by Goel and colleagues to increase the sample diversity, such as purposeful sampling (Goel et al., 2022).

The data presented in this manuscript suggest that exercise behaviors were more compulsive and harmful and %EBW were lower in adolescents with AN during the pandemic compared to before the pandemic. This information may be helpful in informing considerations for providers treating ED patients amidst the pandemic or other chronic, stressful periods. For instance, these data may clarify potential impacts of external stresses of EDs such as war, forced immigration, or severe economic recessions. Careful evaluation or monitoring for increased harmful compensatory behaviors such as exercise may be warranted. This may include alerting parents to the role compensatory behaviors play in maintaining low weight with an additional focus on disrupting these behaviors. An additional consideration includes increased demand for hygiene in the context of the pandemic, such as repeated handwashing, mask‐wearing, and physical distancing. Given the overlap between AN and obsessive–compulsive tendencies/symptoms, where 20%–60% of ED patients have a history of OCD in their lifetime (Kaye et al., 2004), it is possible that these behaviors may become exacerbated in times of duress related to a virus (Mak et al., 2009). Beyond the COVID‐19 pandemic, this growing body of literature cumulatively suggests the harmful impacts of isolation and stress of adolescent development and the presentation of AN in youth.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Eliza Margaret Van Wye: Data curation; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Kyra Citron: Methodology; writing – review and editing. Brittany E Matheson: Writing – review and editing. James D. Lock: Resources; supervision; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Trainee Innovator Grant FY2021.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Datta, N. , Van Wye, E. , Citron, K. , Matheson, B. , & Lock, J. D. (2022). The COVID‐19 pandemic and youth with anorexia nervosa: A retrospective comparative cohort design. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 1–6. 10.1002/eat.23817

Action Editor: Ruth Striegel Weissman

James D. Lock has the following commercial relationship(s) to disclose: National Institute of Mental Health for research funding, ownership interest in the Training Institute for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders, royalties from Oxford Press, Guilford Press, Francis and Taylor, Rutledge, and American Association Press.

Funding information Stanford Trainee Innovator Grant; National Institute of Mental Health

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Agostino, H. , Burstein, B. , Moubayed, D. , Taddeo, D. , Grady, R. , Vyver, E. , Dimitropoulos, G. , Dominic, A. , & Coelho, J. S. (2021). Trends in the incidence of new‐onset anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa among youth during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Canada. JAMA Network Open, 4(12), e2137395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM‐5®). American Psychiatric Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. , & Steer, R. (1993). Beck anxiety inventory manual. Harcourt, Brace, and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. , Steer, R. , & Brown, G. (1996). Manual for the Beck depression inventory‐II. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C. , Brewer, H. , & Ratusny, D. (1993). Behavioral frequency and psychological commitment ‐ necessary concepts in the study of excessive exercising. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 16(6), 611–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Candia, M. , Carvutto, R. , Galasso, L. , & Grimaldi, M. (2021). The exercise dependence at the time of COVID‐19 pandemic: The role of psychological stress among adolescents. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 16, S1937–S1945. [Google Scholar]

- Devoe, J. D. , Han, A. , Anderson, A. , Katzman, D. K. , Patten, S. B. , Soumbasis, A. , Flanagan, J. , Paslakis, G. , Vyver, E. , Marcoux, G. , & Dimitropoulos, G. (2022). The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on eating disorders: A systematic review. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 10.1002/eat.23704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C. G. , Cooper, Z. , & O'connor, M. (2008). In Fairburn C. G. (Ed.), The eating disorder examination (16.0D). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, N. J. , Mathis, K. J. , Egbert, A. H. , Petterway, F. , Breithaupt, L. , Eddy, K. T. , Franko, D. L. , & Graham, A. K. (2022). Accountability in promoting representation of historically marginalized racial and ethnic populations in the eating disorders field: A call to action. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(4), 463–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, L. , Ziv, A. , Vardi, Y. , Hadas, S. , Zuabi, T. , Yeshareem, L. , Gur, T. , Steinling, S. , Scheuerman, O. , & Levinsky, Y. (2022). The effect of COVID‐19 pandemic on hospitalizations and disease characteristics of adolescents with anorexia nervosa. European Journal of Pediatrics, 181(4), 1767–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graell, M. , Morón‐Nozaleda, M. G. , Camarneiro, R. , Villaseñor, Á. , Yáñez, S. , Muñoz, R. , Martínez‐Núñez, B. , Miguélez‐Fernández, C. , Muñoz, M. , & Faya, M. (2020). Children and adolescents with eating disorders during COVID‐19 confinement: Difficulties and future challenges. European Eating Disorders Review., 28(6), 864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hc, K. (2014). Effect size (pp. 1–3). RLCSO L. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, H. W. , & van Hoeken, D. (2003). Review of the prevalence and incidence of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 34(4), 383–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, W. H. , Bulik, C. M. , Thornton, L. , Barbarich, N. , & Masters, K. (2004). Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(12), 2215–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, H. C. (2019). Is it time to ban the P value? JAMA Psychiatry, 76(12), 1219–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, H. C. , Neri, E. , & Spiegel, D. (2020). Wrangling with p‐values versus effect sizes to improve medical decision‐making: A tutorial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(2), 302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange, D. , Doyle, P. , Swanson, S. , Ludwig, K. , Glunz, C. , & Kreipe, R. (2012). Calculation of expected body weight in adolescents with eating disorders. Pediatrics, 129, e438–e446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J. A. , Hartman‐Munick, S. M. , Kells, M. R. , Milliren, C. E. , Slater, W. A. , Woods, E. R. , Forman, S. F. , & Richmond, T. K. (2021). The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the number of adolescents/young adults seeking eating disorder‐related care. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(4), 660–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L'Insalata, A. , Trainor, C. , Bohon, C. , Mondal, S. , Le Grange, D. , & Lock, J. (2020). Confirming the efficacy of an adaptive component to family‐based treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, A. R. , Beard, C. M. , Ofallon, W. M. , & Kurland, L. T. (1991). 50‐Year trends in the incidence of anorexia‐nervosa in Rochester, MN—A population‐based study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148(7), 917–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak, I. W. C. , Chu, C. M. , Pan, P. C. , Yiu, M. G. C. , & Chan, V. L. (2009). Long‐term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. General Hospital Psychiatry, 31(4), 318–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, A. , Kramer, R. A. , Peterson, C. M. , & Mitan, L. (2021). Higher admission and rapid readmission rates among medically hospitalized youth with anorexia nervosa/atypical anorexia nervosa during COVID‐19. Eating Behaviors., 43, 101573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, C. , Plateau, C. R. , Taranis, L. , Brewin, N. , Wales, J. , & Arcelus, J. (2016). The compulsive exercise test: Confirmatory factor analysis and links with eating psychopathology among women with clinical eating disorders. Journal of Eating Disorders, 4, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto, A. K. , Jary, J. M. , Sturza, J. , Miller, C. A. , Prohaska, N. , Bravender, T. , & van Huysse, J. (2021). Medical admissions among adolescents with eating disorders during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Pediatrics, 148(4), e2021052201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhas, L. , Morris, A. , Crosby, R. D. , & Katzman, D. K. (2011). Incidence and age‐specific presentation of restrictive eating disorders in children a Canadian Paediatric surveillance program study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(10), 895–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radomski, A. , Cloutier, P. , Gardner, W. , Pajer, K. , Sheridan, N. , Sundar, P. , & Cappelli, M. (2022). Planning for the mental health surge: The self‐reported mental health impact of Covid‐19 on young people and their needs and preferences for future services. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 41(1), 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Spettigue, W. , Obeid, N. , Erbach, M. , Feder, S. , Finner, N. , Harrison, M. E. , Isserlin, L. , Robinson, A. , & Norris, M. L. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19 on adolescents with eating disorders: A cohort study. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9(1), 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toulany, A. , Kurdyak, P. , Guttmann, A. , Stukel, T. A. , Fu, L. , Strauss, R. , Fiksenbaum, L. , & Saunders, N. R. (2022). Acute care visits for eating disorders among children and adolescents after the onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(1), 42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.