Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the longitudinal cross‐lagged association between family mutuality, depression, and anxiety among Chinese adolescents before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown in 2020.

Background

Limited attention has been paid to the longitudinal links between family mutuality, depression, and anxiety in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Method

We used self‐administered questionnaires to collect data from three high schools and two middle schools in Chengdu City at two time points: Time 1 (T1), December 23, 2019–January 13, 2020; Time 2 (T2), June 16–July 8, 2020. The sample consisted of 7,958 participants who completed two wave surveys before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown. We analyzed the data using cross‐lagged structural equation modeling.

Results

The longitudinal cross‐lagged model showed family mutuality at T1 significantly predicted depression, anxiety, and family mutuality at T2. We observed a decreasing prevalence of depression and anxiety after the COVID‐19 lockdown.

Conclusion

Family mutuality plays an important role in mitigating long‐term mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety. More family‐centered psychological interventions could be developed to alleviate mental health disorders during lockdowns.

Implications

Improving family mutuality (e.g., mutual support, interaction, and caring among family members) could be beneficial for reducing mental health disorders among Chinese adolescents during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Keywords: anxiety, Chinese adolescents, COVID‐19, depression, family mutuality

INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic and consequent implementation of lockdown policy have affected the economic, social interaction, and livelihood activities of people worldwide (De Picker, 2021). To control the spread of the COVID‐19 pandemic, China implemented a national lockdown policy on January 23, 2020, which included the closure of schools to protect students' health and safety (Shi & Hall, 2020). However, the public health measures implemented, such as staying at home, wearing masks, and maintaining social distance to decrease the spreading risk of COVID‐19, have been found to result in lonely, stressful, solitary feelings, and negatively impact mental health (Vai et al., 2021).

Adolescence is a crucial and decisive period for developing social and emotional habits, and mental well‐being (Penner et al., 2021). Adolescents could be susceptible to serious and possible lifelong mental health disorders when suffering from overriding stressors during public health emergencies (Penner et al., 2021). A cross‐sectional study of 8,140 Chinese adolescents reported an increased prevalence of up to 43.7% and 37.4% for depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively (S.‐J. Zhou et al., 2020). Similar research has indicated the expected deterioration of mental health in the United Kingdom (Pierce et al., 2020) and Switzerland (Elmer et al., 2020) during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Meanwhile, different results have been reported in other countries and groups, such as an unchanged mental status in adolescents in the Netherlands (Van Zyl et al., 2021) and decreased prevalence of mental health problems in young American adolescents (Penner et al., 2021). Given the contradictory results regarding the influence of COVID‐19 lockdowns on individual's mental health, the influence of the COVID‐19 pandemic on long‐term mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, needs to be further explored among adolescents via longitudinal research (Li et al., 2020).

The lockdown and quarantine policies during the COVID‐19 pandemic changed the availability of adolescents' social networks among peers and friends as adolescents returned to their family, which made the family a key social support resource (Shi & Hall, 2020). Such support, along with love, interaction, and caring among family members, is encompassed in the concept of family mutuality (Shek & Ma, 2010). Family function (e.g., family support, relationship, and status) has been reported to protect adolescents from psychological illnesses (e.g., Bekhet et al., 2012; Rowe, 2012). For example, based on a sample of 898 American young adults, C. H. Liu et al. (2020) indicated that more family social support is significantly associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Intergenerational family systems theory proposes that family dysfunction of original relation patterns could bring higher stress and increase vulnerability to mental health disorders (Bray et al., 1987). Recent research has shown that positive relationships with family and friends buffered against stress during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Gallegos et al., 2022). A comprehensive review of 50 studies revealed the vital role of family support in improving the youth's mental health (Hoagwood et al., 2010). Meanwhile, owing to collectivist socialization attributes, the Chinese tend to highlight the role of the family (Shek & Ma, 2010). In a survey of 817 Chinese youth exposed to disasters, family support is the critical factor that helps promote mental help seeking and recovery (Shi & Hall, 2021). However, the majority of previous studies have used a cross‐sectional design to explore the influence of family support on mental health among youth. The influence of family mutuality on long‐term mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, has remained a poorly explored area, especially in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Family mutuality reflects the quality of intimacy and openness in connections with families (Shek & Ma, 2010). With the lockdown associated with the COVID‐19 pandemic, adolescents returned home to live with their families (e.g., parents, siblings, or grandparents) for quarantine and sharing resources together. This situation potentially influences family members to behave in different ways, which underlies in the quality of family mutuality (Gallegos et al., 2022). Positive family mutuality could be potentially beneficial for remitting potential maladaptive psychosocial outcomes emerging from the COVID‐19 lockdown, such as negative feelings, decreasing self‐esteem, and abnormal behavior among adolescents (Shek & Ma, 2010). Furthermore, considering the potentially negative impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health, relatively few studies explored the influence of positive family mutuality on mitigating the links between mental health (e.g., depression and anxiety) among adolescents. Therefore, we aim to estimate the association between depression, anxiety, and family mutuality among adolescents before and after COVID‐19 lockdown and understand the possible function of family mutuality in buffering against mental health issues.

The cross‐sectional design (e.g., Dellafiore et al., 2021) is limited to delineating concurrent associations between variables, as previously discussed. To our knowledge, no previous study has explored the effect of family mutuality on long‐term mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, among Chinese adolescents during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Also, to our knowledge, previous studies have only explored family support but have not examined the other possible dimensions of family functions, such as harmony, love, and interactions included in family mutuality (e.g., Rowe, 2012; Shek & Ma, 2010). Furthermore, studies on the prevalence of mental health disorders among the exposed population before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown have yielded inconsistent results (e.g., Penner et al., 2021; Pierce et al., 2020). As the discrepant results indicate, more studies need to further explore and demonstrate the development of mental health disorders among adolescents before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown. In response to the abovementioned research gaps in the literature, the current study adopted two objectives. First, we tested the prevalence of depression and anxiety among Chinese adolescents before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown. Second, we used a cross‐lagged model with three covariates (i.e., age, sex, and COVID‐19 pandemic exposure) to examine the associations between depression symptom, anxiety symptom, and family mutuality in both wave studies. The following hypotheses were proposed in this study.

H1: Family mutuality before the COVID‐19 lockdown significantly and negatively predicted the depression and anxiety symptoms after the COVID‐19 lockdown.

H2: Depression and anxiety symptoms before the COVID‐19 lockdown significantly and negatively predicted the family mutuality after the COVID‐19 lockdown.

H3: There is an increasing trend of depression and anxiety severities among Chinese adolescents before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown.

H4: Family mutuality after the COVID‐19 lockdown was significantly affected by sex, age, and COVID‐19 exposure.

METHODS

Data set

Our study used the data set of the Chengdu Positive Child Development (CPCD) survey, which conducted a two‐wave study among Chinese adolescents before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown (Zhao et al., 2022). Chengdu was one of the largest and typical cities affected by the COVID‐19 pandemic in southwest China. The CPCD survey used a cluster sampling method to select these five schools in Chengdu (three high schools and two middle schools): one downtown, two suburbs in the south, and two suburbs in the north of Chengdu. Data were collected by distributing self‐administered questionnaires to students at these schools. Time 1 (T1) data were collected between December 23, 2019, and January 13, 2020, before the COVID‐19 lockdown in China. Time 2 (T2) data collection was completed between June 16 and July 8, 2020, when the COVID‐19 pandemic had been under relative control in China and schools had been excluded from the lockdown prohibition. All participants of this study experienced the worst period of the COVID‐19 pandemic in Chengdu and the social distancing required by the national lockdown policy, such as stay‐at‐home, school closure, and community closure. All the participants and their legal guardians signed the study consent form and were informed of the research objectives, privacy protection, data retention, and research process. The study was approved by the research ethics committees of the research university and administrative offices at the data collection schools (approval no. K2020025).

Of the 10,370 students invited to complete the questionnaires, 8,749 submitted valid responses for the T1 study (response rate: 84.37%), of whom 51.62% identified as male. All invalid responses, such as keeping all blanks (n = 1,559) or showing the exact same (n = 42) or wrong response (n = 20) were deleted in the data clean. The participants' mean age was 12.02 years (SD = 2.30). The T2 study had 7,958 participants (response rate: 76.74%), of whom 51.67% identified as male. Their mean age was 11.74 years (SD = 2.15). A total of 791 participants were lost to follow‐up. The present study analyzed data from the 7,958 participants who completed both T1 and T2 studies.

Measures

Depression

We used the Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D) to evaluate depression symptoms in the past week across the two wave studies (William Li et al., 2010). This tool is a 20‐item self‐report measure for depression (J. Liu et al., 2019). Each item is rated on a 4‐point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (a lot). This scale includes four reversed items (Items 4, 8, 12, and 16) that are scored in the opposite direction. A sample item is “I felt like I couldn't pay attention to what I was doing.” The total of all item scores indicated the degree of depressive symptomatology. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. The CES‐D has a total possible score of 60, and a score of 15 is the recommended score for the diagnosis of depression (William Li et al., 2010). Previous studies have demonstrated the validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the CES‐D (e.g., Jiang et al., 2019; William Li et al., 2010). The scale showed good reliability in both waves of data (Cronbach's αs were .87 for T1 and .89 for T2).

Anxiety

We used the 41‐item Chinese Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) to test the anxiety symptoms in the past 3 months across both data waves (Su et al., 2008). Each item is rated on a 3‐point Likert scale (0 = never, 2 = often). A sample item is “When I feel frightened, it is hard to breathe.” Potential scores range from 0 to 82 with higher scores representing more severe levels of anxiety. A total score over 25 indicates the existence of anxiety disorder (Su et al., 2008). The Chinese version of SCARED has been proven to have good validity and reliability (e.g., Su et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2002). The scale reliability was excellent in the two‐wave data (Cronbach's αs were .95 at T1 and .95 at T2).

Family mutuality

Family mutuality refers to the quality of intimacy, love, mutual communication, harmony, interaction, and caring among family members (Shek & Ma, 2010). A 12‐item subscale of the Chinese Family Assessment Instrument (C‐FAI) was used to assess family mutuality in both wave studies (Shek & Ma, 2010). Each item was rated on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 = does not fit our family; 5 = very fit to our family). The sample items are “Family members support each other”; “Family members love each other”; and “Family members care about each other.” These 12 items were scored in the opposite order. A higher total score indicates a greater level of family mutuality. The C‐FAI has shown good reliability and validity in previous studies (Shek, 2002; Shek & Ma, 2010). The internal reliability of the C‐FAI was also excellent in both wave data (Cronbach's αs were .92 at T1 and .94 at T2).

Covariates

We collected demographic information, including age, sex, and COVID‐19 pandemic exposure. We formulated nine items to test for COVID‐19 pandemic exposure at T2 for the Chinese adolescents, grounded on the actual situation and previous literature (Luo et al., 2021). Four items used a 4‐point scale (1 = not at all; 4 = extremely severe) to test the perceived severity, threat, infectious risk, and prevention capability toward the COVID‐19 pandemic. One dichotomous item examined whether there was a COVID‐19 pandemic confirmed case among family members (1 = no, 2 = yes). Four questions were used to measure the impact of COVID‐19 pandemic exposure on their study, daily diet, social life, and recreational activities, with a rating score from 1 (none) to 4 (very strong influence). The total score was the sum of all items, with a higher score denoting a higher degree of COVID‐19 pandemic exposure.

Statistical analysis

Our threefold data analysis procedures were collected using computer software IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 24.0) and AMOS 23.0 (Arbuckle, 2014). First, we conducted descriptive analysis and correlation matrix for all study variables using SPSS. Second, we analyzed the differences between 7,958 participants and 791 respondents who were lost to tracking at T2, based on the independent samples t test via SPSS. Third, we performed structural equation modeling to examine the goodness of the longitudinal cross‐lagged model and relations between the main constructs (depression symptom, anxiety symptom, and family mutuality at T1 and T2) under the controlling covariates (i.e., age, sex, and COVID‐19 pandemic exposure) via AMOS. Bootstrapping was applied using 5,000 bootstrapped replications. The parameters were tested using maximum likelihood estimation. We referred to some recommended goodness‐of‐fit indices to evaluate the quality and significant influence of paths in the model (Hou et al., 2002), including χ2/df (degrees of freedom), root‐mean‐square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root‐mean‐square residual (SRMR), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), normed fit index (NFI), and comparative fit index (CFI). According to previous suggestions for good model fit indices (Hou et al., 2002), χ2/df should be lower than 5.0, whereas the NFI, TLI, and CFI should be greater than .95. The RMSEA should be less than .05. The SRMR should be less than .06. A p value below .05 or .001 indicated a significant difference in this study.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographics of the participants. No significant differences were detected between study participants with completed data at T1 and T2 and those participants who did not complete T2 follow‐up assessments for study variables, including sex (p = .749) and anxiety (p = .554), apart from age (p < .001), depression symptom (p < .05), and family mutuality (p < .05). Participants with older age, higher family mutuality, and more depression symptoms were more likely to have dropped out of the study prior to the follow‐up survey.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 7,958)

| Variable | (N, %) |

|---|---|

| Age (7–17 years) | M = 11.74, SD = 2.15 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 4,112 (51.67%) |

| Female | 3,846 (48.33%) |

| COVID‐19 exposure | M = 21, SD = 4.05 |

| Depression symptom severity | |

| T1 | Range: 0–60, M = 14.40, SD = 10.16 |

| N Yes = 3,078 (38.68%) | |

| T2 | Range: 0–60, M = 14.36, SD = 10.62 |

| N Yes = 2,924 (36.74%) | |

| Anxiety symptom severity *** | |

| T1 | Range: 0–82, M = 17.09, SD = 14.74 |

| N Yes = 2,035 (25.57%) | |

| T2 | Range: 0–82, M = 15.21, SD = 15.12 |

| N Yes = 1,774 (22.29%) |

Note. N yes = number of participants with anxiety or depression; Range = full range of scores; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2. Diagnostic cut‐off values for depression and anxiety symptoms severity were 15 and 25, respectively.

p < .001 (paired‐samples t test).

Intercorrelation

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the study variables. After controlling for sex, age, and COVID‐19 pandemic exposure, all variables moderately or highly correlated with each other except for anxiety at T2 and family mutuality at T1 (r = −.181, p < .001), which showed relatively low correlations. In addition, family mutuality at T1 and T2 had significantly negative correlations with both depression and anxiety symptoms longitudinally.

TABLE 2.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables (N = 7,958)

| # | Variable | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T1 Depression | 14.40 ± 10.16 | – | .519 *** | .578 *** | .381 *** | −.402 *** | −.289 *** |

| 2 | T2 Depression | 14.36 ± 10.62 | .528 *** | – | .386 *** | .590 *** | −.271 *** | −.437 *** |

| 3 | T1 Anxiety | 17.09 ± 14.74 | .583 *** | .403 *** | – | .498 *** | −.281 *** | −.230 *** |

| 4 | T2 Anxiety | 15.21 ± 15.12 | .391 *** | .605 *** | .516 *** | – | −.181 *** | −.340 *** |

| 5 | T1 Family mutuality | 50.27 ± 10.43 | −.411 *** | −.287 *** | −.289 *** | −.196 *** | – | .365 *** |

| 6 | T2 Family mutuality | 51.92 ± 10.00 | −.299 *** | −.454 *** | −.245 *** | −.359 *** | .375 *** | – |

Note. The number in the lower left is the correlation coefficient without controlling for age and sex; the number in the top right is the correlation coefficient after controlling for age, sex, and COVID‐19 pandemic exposure. Depression and anxiety refer to depression and anxiety symptoms severity.

p < .001.

Measurement invariance

Table 3 shows the measurement invariance testing results. According to the recommended procedures of testing measurement invariance (Byrne, 2010), configural (Model 1), metric (Model 2), intercept (Model 3), and residual (Model 4) invariance analyses were conducted sequentially. The configural invariance reasonably holds because of the excellent model fit across both study waves. Moreover, based on the recommended criteria (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), the p value of the chi‐square test above .001 and ∆CFI below or equal to .01 indicate measurement invariance across both study waves. There is a non‐invariant intercept across study waves (Δdf = 4, Δχ2 = 41.199; ΔCFI < .001, p < .001). Results revealed the intercepts were higher in the Wave 1 study. No difference was found by testing the residual invariance (Δdf = 5, Δχ2 = 3.882; ΔCFI < .001, p = .567), which provided evidence for the partial measurement invariance across study waves.

TABLE 3.

Measurement invariance results across wave data

| Models tested | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | NFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | ΔCFI | (df) Δχ2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 model | 1331.750 | 156 | 8.537 | .989 | .987 | .985 | .031 | .052 | – | – | – |

| Wave 2 model | 1398.133 | 156 | 8.962 | .990 | .989 | .986 | .032 | .031 | – | – | – |

| Model 1 (configural) | 2729.882 | 312 | 8.750 | .989 | .988 | .986 | .022 | .052 | – | – | – |

| Model 2 (metric) | 2744.146 | 321 | 8.549 | .989 | .988 | .986 | .022 | .052 | <.001 | (9) 14.264 | .113 |

| Model 3 (intercept) | 2785.345 | 325 | 8.570 | .989 | .988 | .986 | .022 | .052 | <.001 | (4) 41.199 | <.001 |

| Model 4 (residual) | 2789.227 | 330 | 8.452 | .989 | .988 | .986 | .022 | .052 | <.001 | (5) 3.882 | .567 |

Note. CFI = comparative fit index; df = degree of freedom; NFI = normed fit index; RMSEA = root‐mean‐square error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root‐mean‐square residual; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index. p value: chi‐square test for the comparative models; Wave 1 = data collection before COVID‐19 lockdown (baseline study); Wave 2 = data collection after COVID‐19 lockdown (follow‐up study). N = 7,958 for each wave study.

In order to further explore the sources of intercept non‐invariance, a follow‐up analysis was conducted to examine intercept invariance across each of the study variable clusters sequentially (i.e., depression symptom, anxiety symptom, and family mutuality). The depression and anxiety symptoms clusters showed the intercept invariance across waves (Δdf = 2, Δχ2 = 1.776, p = .411 and Δdf = 3, Δχ2 = 1.235, p = .745, respectively). The family mutuality cluster demonstrated a non‐invariant intercept (Δdf = 4, Δχ2 = 30.381, p < .001). No other difference was found in study variables in terms of invariance testing.

According to the recommendation of previous researchers (Crespo et al., 2011; Hanssen‐Doose et al., 2021), when stability coefficients are equal to or higher than 0.4, there is a measurement invariance. The results showed that stability coefficients among family mutuality, depression, and anxiety symptoms in both waves were 0.40, 0.61, and 0.56, respectively, which demonstrated the measurement invariance across waves.

Collinearity test

Based on prior research recommendations (Miles, 2005), the variance inflation factor (VIF) above 4 or tolerance below 0.25 represents that multicollinearity could exist. The results of the multiple collinearity test showed that tolerances and VIF of depression symptom (VIF = 1.678; tolerance = 0.596), anxiety symptom (VIF = 1.522; tolerance = 0.657), and family mutuality (VIF = 1.208; tolerance = 0.828) at T1 were within limits. Therefore, there was a low probability of collinearity problems between variables.

Prevalence of depression and anxiety

The prevalence of depression and anxiety was 38.68% and 25.57% at T1 and 36.74% and 22.29% at T2, respectively. The prevalence of depression and anxiety showed a decreasing trend after the COVID‐19 lockdown.

Cross‐lagged path model

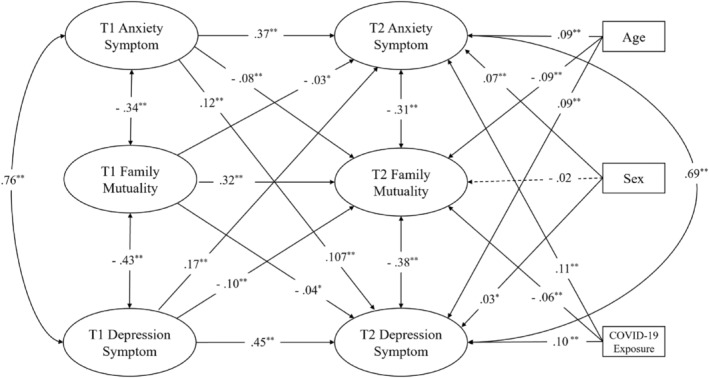

The results showed that the longitudinal cross‐lagged model revealed excellent goodness‐of‐fit indices when controlling for the three covariates of age, sex, and COVID‐19 pandemic exposure: χ2 (785) = 3827.607, p < .001, χ2/df = 4.88, CFI = .987, NFI = .984, TLI = .984, RMSEA (90% confidence interval [CI]) = .019 [.021, .023], SRMR = .036 (see Figure 1). Moreover, the results showed significant concurrent associations between depression symptom and family mutuality at both T1 (r = −.34, p < .001) and T2 (r = −.31, p < .001). Similarly, anxiety and family mutuality showed significant co‐instantaneous links at both T1 (r = −.43, p < .001) and T2 (r = −.38, p < .001).

FIGURE 1.

Longitudinal cross‐lagged model with bidirectional effects among depression, anxiety, and family mutuality Note. Dashed lines indicate insignificant paths. Depression and anxiety symptom severity were treated as continuous variables in this model. COVID‐19 exposure refers to exposure to the COVID‐19 pandemic. *p < .05. ** p < .001.

Results displayed that lower family mutuality at T1 was significantly associated with greater depression (β = −.037, standard error [SE] = 0.046, effect size [ES] = −0.037, p = .003) and anxiety (β = −.026, SE = 0.077, ES = −0.026, p = .031) symptoms at T2. A lower level of family mutuality at T1 was significantly associated with the worst level of family mutuality at T2 (β = .322, SE = 0.015, ES = 0.322, p < .001). Moreover, higher depression symptom at T1 was significantly associated with more anxiety (β = .170, SE = 0.042, ES = 0.170, p < .001) and depression symptom (β = .092, SE = 0.026, ES = 0.446, p < .001) at T2, but lower family mutuality (β = −.104, SE = 0.007, ES = −0.104, p < .001) at T2. Additionally, higher anxiety at T1 was significantly linked with higher depression symptom (β = .121, SE = 0.044, ES = 0.121, p < .001) and anxiety (β = .373, SE = 0.076, ES = 0.373, p < .001) at T2, but less family mutuality (β = −.080, SE = 0.012, ES = −0.080, p < .001) at T2.

Older age (β = .089, SE = 0.021, ES = 0.089, p < .001), being female (β = .109, SE = 0.011, ES = 0.073, p < .001), and more exposure to COVID‐19 pandemic (β = .073, SE = 0.089, ES = 0.109, p < .001) were significantly associated with greater anxiety at T2. Likewise, older age (β = .092, SE = 0.012, ES = 0.092, p <. 001), being female (β = .032, SE = 0.053, ES = 0.032, p = .001), and more exposure to the COVID‐19 pandemic (β = .102, SE = 0.007, ES = 0.102, p < .001) were significantly linked with greater depression symptom at T2. In addition, younger age (β = −.093, SE = 0.004, ES = −0.093, p < .001) and less exposure to the COVID‐19 pandemic (β = −.056, SE = 0.002, ES = −0.056, p < .001) were significantly associated with more family mutuality at T2. However, sex and family mutuality at T2 showed no significant associations (β = −.017, SE = 0.015, ES = −0.017, p = .106). The results indicated that two out of four hypotheses were supported by our data (H1 and H2). One hypothesis was partially supported (H4), but another hypothesis was disproved by the data (H3).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to explore the longitudinal cross‐lagged associations between depression symptom, anxiety symptom, and family mutuality and to track the developing trajectory of psychological status among Chinese adolescents before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown. To our knowledge, this is the first empirical large‐sample study to investigate longitudinally prospective impact of family mutuality on long‐term mental health disorders among Chinese adolescents before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown.

The results indicated that a greater level of family mutuality before the COVID‐19 lockdown significantly predicted lower severity of depression and anxiety symptoms after the lockdown, suggesting that better family mutuality could potentially alleviate the development of mental health disorders among adolescents exposed to COVD‐19. Previous research supports the important role of the family in mitigating mental health disorders (e.g., Hoagwood et al., 2010; Rowe, 2012; Ryan et al., 2015). For example, a study with a sample of 1,091 parents and children in the United States found that positive communication between family members is significantly associated with decreased mental problems, such as depression and anxiety (Felix et al., 2020). Furthermore, family positive involvement plays an important role in patients recovering from mental health disorders (e.g., Akbari et al., 2018; Pavitra et al., 2019).

Various restrictions implemented to avoid COVID‐19 pandemic transmission, such as home quarantine, maintaining social distance, and reducing gatherings have resulted in a substantial change in people's lives and social activities (Shi & Hall, 2020). The family became a center of social life as people had to stay with their families longer (Shi & Hall, 2020). Previous research reported that the Chinese prefer to seek mental support from families, which could be beneficial for reducing the risk of mental health disorders during the pandemic (Shi et al., 2020). Indeed, family support could help reduce feelings of loneliness, which could relieve depressive symptoms during COVID‐19 lockdown (Mariani et al., 2020). Previous research with a large sample of 26,069 adolescents highlighted that families have a certain and overriding impact on mental or socioemotional health among adolescents (e.g., Elgar et al., 2013). These results emphasize the importance of developing psychological approaches to promoting family mutuality, including increasing family interaction, harmony, understanding, communication, and mutual support, to relieve mental symptomatology among adolescent populations during a large‐scale pandemic crisis.

The results showed that depression and anxiety symptoms at T1 significantly and negatively predicted family mutuality at T2, which suggested that a higher level of depression and anxiety symptoms before the COVID‐19 pandemic could strain family mutuality after the COVID‐19 lockdown. Previous research indirectly supports this finding: Patients with mental health disorders burden their families in terms of caregiving, therapy expenses, and social stigma, which could easily result in imminent conflict and negative environment within the family (e.g., Akbari et al., 2018). Moreover, the family can be a major avenue for expressing negative emotions among adolescents, in which the family atmosphere could become more strained when observing various injunction and lockdown policies required by the government during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Thorisdottir et al., 2021). Additionally, adolescent patients with depression and anxiety have many negative emotions (e.g., low mood, fear, aversion to argument, lack of passion, sadness, and displeasure) and behavioral dysfunction (e.g., appetite decrease/increase, insomnia, difficulty concentrating, physical fatigue, and overreaction to daily activities), which could potentially provoke the tense relationships of family members (Racine et al., 2020). Consistent with previous research, our study suggested that the improvement of adolescents' mental health could benefit family mutuality and well‐being to a large extent.

Meanwhile, our study noted a decreasing trend of mental health disorders (i.e., depression and anxiety) among Chinese adolescents from before to after the COVID‐19 lockdown. These results are inconsistent with the majority of the relevant studies. For example, based on a national sample of 13–18‐year‐old adolescents (n = 59,701) in Iceland, a longitudinal study reported rapidly growing depressive symptoms and worsened mental well‐being during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Thorisdottir et al., 2021). Another study with a sample of 3,572 adolescents aged 11 to 16 years found that the clinical prevalence of depression and anxiety slightly surged from before to during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Hafstad et al., 2021). A study analyzing 4,909 online participants indicated that adolescents are more likely to experience moderate or severe depressive and anxiety symptoms during the COVID‐19 pandemic compared with adults (Murata et al., 2021). Moreover, a prior study reported that exposure to the COVID‐19 pandemic could lead to augmented psychiatric disorders among adolescents, including depressive and anxiety symptoms, owing to mental vulnerability and frigidity in the adolescent growth stage (Guessoum et al., 2020). Another study in England reported an increasing incidence rate of mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, among youths before and during the COVID‐19 lockdown (Newlove‐Delgado et al., 2021).

Nonetheless, our results are consistent with some research that reported a diminished tendency in mental health disorders (e.g., Hollenstein et al., 2021; Penner et al., 2021). Possible explanations for these contradictory results are that decreased academic pressure at school, increasing family companionship, and extended sleeping time could help alleviate the incidence of mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety, among adolescents during the implementation of home quarantine in the time of the COVID‐19 lockdown (Francisco et al., 2020; Hoagwood et al., 2010; Shi & Hall, 2020). Additionally, social support for mental health has been massively promoted in China, such as setting up online mental health counseling, providing online free psychological courses, organizing mental health support hotspots, and increasing the number of community mental health workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic (S. Liu et al., 2020; J. Zhou et al., 2020), which could be helpful for mitigating the mental health problems among Chinese adolescents during the COVID‐19 pandemic. One additional explanation is that for our population, when the lockdown ended, life resumed similarly to before the pandemic lockdown. Although the lockdown itself was stressful, it was not sufficient to cause long‐term mental health issues. The situation in other counties was quite different: Because widespread lockdowns did not occur, the ongoing disruptions to life continued, which may account for these differences in mental health trajectories between countries.

Lastly, the results showed that sex did not significantly predict family mutuality at T2. This result was different from some previous studies (e.g., Tam Ashing et al., 2003; You & Lu, 2014). These studies reported that Chinese men tend to have a stronger influence on family relations because they could receive more family support, compared to Chinese women. Another study indicated that Chinese men are valued more in the family as breadwinners and they were viewed to play a more important role in influencing family harmony than women (Sigal & Nally, 2004). One possible explanation for the difference in findings was that gender equality has been emphasized more in modern Chinese society and both men and women are equally affected in the family (Hu & Scott, 2016). This could decrease the influence of different sexes on family mutuality among Chinese adolescents. Prior research has mentioned that other variables could play a more important role in influencing family happiness and harmonies than sex, such as family income, family formation, and robust work ethic (Chan et al., 2011).

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, this longitudinal study only evidenced the predictive links between variables; causal inferences remain limited without an experimental study. Second, owing to the limited length of the research questionnaire, this concurrent study could not cover all family‐related factors influencing mental health disorders. Other factors could be further explored, such as family communication frequency, conflict, and parental control (Shek & Ma, 2010). Moreover, future studies should include more COVID‐19–specific variables to further explore the function of the family on long‐term depression and anxiety symptoms during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Third, this study only collected data from adolescent individuals. As family mutuality involves more than one person, future study is suggested to include more family members, such as parents or siblings, to further explore the issue via nesting different levels of analysis. Finally, we only included data collected as a part of a two‐wave study before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown. Due to the limitations with this model, there could be a different significant association between family mutuality, depression, and anxiety symptoms over a longer period (Curran & Bauer, 2011). Future studies should conduct a longer study to follow the influence of family‐related factors on long‐term mental health disorders (Robinson et al., 2022).

CONCLUSIONS

The results demonstrated that family mutuality played a vital role in influencing long‐term mental health disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety) among Chinese adolescents exposed to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Moreover, our study found that the prevalence of depression (38.68% to 36.74%) and anxiety (25.57% to 22.29%) displayed a declining tendency among Chinese adolescents before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown. The results revealed the potentially beneficial impact of home quarantine as part of lockdown policies on reducing mental health disorders among Chinese adolescents exposed to the COVID‐19 pandemic. This study highlighted the importance of improving family mutuality in protecting Chinese adolescents from mental health problems during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

IMPLICATIONS

Our research broadened the previous literature by exploring the longitudinal links between depression, anxiety, and family mutuality via the cross‐lagged model and specifically tracking the longitudinal change trend of mental health among Chinese adolescents before and after the COVID‐19 lockdown. Additionally, the time‐lagged study design could help elucidate the prospective bidirectional associations between depression, anxiety, and family mutuality over a long period of time. Future studies could further develop family‐centered interventions and examine their benefits for preventing and alleviating depression and anxiety symptoms following a public health emergency. Additionally, future studies should conduct a longer‐term survey to track the change trend of mental health disorders and expose adolescents' resilience, barriers, and facilitators of mental health help‐seeking after the COVID‐19 lockdown. Finally, our valuable findings call for future empirical research on the influence of family‐related factors on long‐term mental health disorders among youth.

Shi, W. , Yuan, G. F. , Hall, B. J. , Zhao, L. , & Jia, P. (2022). Chinese adolescents' depression, anxiety, and family mutuality before and after COVID‐19 lockdowns: Longitudinal cross‐lagged relations. Family Relations, 1–15. 10.1111/fare.12761

Funding information This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (20827044B4020), The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (19H0642), Wuhan University Specific Fund for Major School‐level Internationalization Initiatives (WHU‐GJZDZX‐PT07), and the International Institute of Spatial Lifecourse Health (ISLE).

Author note: PJ, LZ, and their research assistants completed the study design, preparation, and data collection. WS and GFY completed the literature research, data analysis, drafting of the manuscript, and submission of this manuscript. PJ, LZ, and BJH revised the manuscript. All authors contributed equally to manuscript modification and approved the final manuscript. The authors have no competing interests. We pay tribute to all frontline workers against COVID‐19 who have protected countless lives. We are deeply thankful to all the study participants, administrative staff, and data collection assistants.

Contributor Information

Li Zhao, Email: zhaoli@scu.edu.cn.

Peng Jia, Email: jiapengff@hotmail.com, Email: zhaoli@scu.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

- Akbari, M. , Alavi, M. , Irajpour, A. , & Maghsoudi, J. (2018). Challenges of family caregivers of patients with mental disorders in Iran: A narrative review. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 23(5), 329–337. 10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_122_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2014). AMOS (Version 23.0) [Computer software]. IBM SPSS.

- Bekhet, A. K. , Johnson, N. L. , & Zauszniewski, J. A. (2012). Resilience in family members of persons with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(10), 650–656. 10.3109/01612840.2012.671441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J. H. , Harvey, D. M. , & Williamson, D. S. (1987). Intergenerational family relationships: An evaluation of theory and measurement. Psychotherapy, 24(3), 516–528. 10.1037/h0085749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S. S. C. , Viswanath, K. , Au, D. W. , Ma, C. M. S. , Lam, W. W. T. , Fielding, R. , … Lam, T. H. (2011). Hong Kong Chinese community leaders' perspectives on family health, happiness and harmony: A qualitative study. Health Education Research, 26(4), 664–674. 10.1093/her/cyr026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G. W. , & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness‐of‐fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, C. , Kielpikowski, M. , Pryor, J. , & Jose, P. E. (2011). Family rituals in New Zealand families: Links to family cohesion and adolescents' well‐being. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(2), 184–193. 10.1037/a0023113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran, P. J. , & Bauer, D. J. (2011). The disaggregation of within‐person and between‐person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 583–619. 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellafiore, F. , Arrigoni, C. , Palpella, F. , Diazzi, A. , Orrico, M. , Magon, A. , … Caruso, R. (2021). Effects of mutuality, anxiety, and depression on quality of life of patients with heart failure: A cross‐sectional study. Creative Nursing, 27(3), 181–189. 10.1891/CRNR-D-20-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Picker, L. J. (2021). Closing COVID‐19 mortality, vaccination, and evidence gaps for those with severe mental illness. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(10), 854–855. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00291-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgar, F. J. , Craig, W. , & Trites, S. J. (2013). Family dinners, communication, and mental health in Canadian adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(4), 433–438. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer, T. , Mepham, K. , & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students' social networks and mental health before and during the COVID‐19 crisis in Switzerland. PloS One, 15(7), Article e0236337. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix, E. D. , Afifi, T. D. , Horan, S. M. , Meskunas, H. , & Garber, A. (2020). Why family communication matters: The role of co‐rumination and topic avoidance in understanding post‐disaster mental health. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(11), 1511–1524. 10.1007/s10802-020-00688-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco, R. , Pedro, M. , Delvecchio, E. , Espada, J. P. , Morales, A. , Mazzeschi, C. , & Orgilés, M. (2020). Psychological symptoms and behavioral changes in children and adolescents during the early phase of COVID‐19 quarantine in three European countries. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, Article 570164. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.570164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos, M. I. , Zaring‐Hinkle, B. , & Bray, J. H. (2022). COVID‐19 pandemic stresses and relationships in college students. Family Relations, 71(1), 29–45. 10.1111/fare.12602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guessoum, S. B. , Lachal, J. , Radjack, R. , Carretier, E. , Minassian, S. , Benoit, L. , & Moro, M. R. (2020). Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID‐19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 291, Article 113264. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafstad, G. S. , Sætren, S. S. , Wentzel‐Larsen, T. , & Augusti, E. M. (2021). Adolescents' symptoms of anxiety and depression before and during the Covid‐19 outbreak–A prospective population‐based study of teenagers in Norway. The Lancet Regional Health–Europe, 5, Article 100093. 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen‐Doose, A. , Kunina‐Habenicht, O. , Oriwol, D. , Niessner, C. , Woll, A. , & Worth, A. (2021). Predictive value of physical fitness on self‐rated health: A longitudinal study. Scandinavian. Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 31(S1), 56–64. 10.1111/sms.13841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood, K. E. , Cavaleri, M. A. , Olin, S. S. , Burns, B. J. , Slaton, E. , Gruttadaro, D. , & Hughes, R. (2010). Family support in children's mental health: A review and synthesis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13(1), 1–45. 10.1007/s10567-009-0060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein, T. , Colasante, T. , & Lougheed, J. P. (2021). Adolescent and maternal anxiety symptoms decreased but depressive symptoms increased before to during COVID‐19 lockdown. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 517–530. 10.1111/jora.12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, K. T. , Wen, Z. L. , & Cheng, Z. J. (2002). Structural equation model and its application. Educational Science Publishing House.

- Hu, Y. , & Scott, J. (2016). Family and gender values in China: Generational, geographic, and gender differences. Journal of Family Issues, 37(9), 1267–1293. 10.1177/0192513X14528710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L. , Wang, Y. , Zhang, Y. , Li, R. , Wu, H. , Li, C. , … Tao, Q. (2019). The reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D) for Chinese university students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, Article 315. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. W. , Yu, H. , Miller, D. J. , Yang, F. , & Rouen, C. (2020). Novelty seeking and mental health in Chinese university students before, during, and after the COVID‐19 pandemic lockdown: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 600739. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.600739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. H. , Zhang, E. , Wong, G. T. F. , Hyun, S. , & Hahm, H. C. (2020). Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Research, 290, Article 113172. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. , Liu, C. X. , Wu, T. , Liu, B. P. , Jia, C. X. , & Liu, X. (2019). Prolonged mobile phone use is associated with depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 259, 128–134. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. , Yang, L. , Zhang, C. , Xiang, Y. T. , Liu, Z. , Hu, S. , & Zhang, B. (2020). Online mental health services in China during the COVID‐19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), e17–e18. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W. , Zhong, B. L. , & Chiu, H. F. K. (2021). Prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students amid the COVID‐19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 30, Article e31. 10.1017/S2045796021000202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, R. , Renzi, A. , Di Trani, M. , Trabucchi, G. , Danskin, K. , & Tambelli, R. (2020). The impact of coping strategies and perceived family support on depressive and anxious symptomatology during the coronavirus pandemic (COVID‐19) lockdown. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, Article 587724. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.587724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles, J. (2005). Tolerance and variance inflation factor. In Everitt B. S. & Howell D. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. Wiley. 10.1002/0470013192.bsa683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murata, S. , Rezeppa, T. , Thoma, B. , Marengo, L. , Krancevich, K. , Chiyka, E. , … Melhem, N. M. (2021). The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID‐19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depression and Anxiety, 38(2), 233–246. 10.1002/da.23120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlove‐Delgado, T. , McManus, S. , Sadler, K. , Thandi, S. , Vizard, T. , Cartwright, C. , & Ford, T. (2021). Child mental health in England before and during the COVID‐19 lockdown. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(5), 353–354. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavitra, K. S. , Kalmane, S. , Kumar, A. , & Gowda, M. (2019). Family matters! – The caregivers' perspective of Mental Healthcare Act 2017. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(4), S832–S837. 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_141_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner, F. , Ortiz, J. H. , & Sharp, C. (2021). Change in youth mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic in a majority Hispanic/Latinx US sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(4), 513–523. 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, M. , Hope, H. , Ford, T. , Hatch, S. , Hotopf, M. , John, A. , … Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine, N. , Cooke, J. E. , Eirich, R. , Korczak, D. J. , McArthur, B. , & Madigan, S. (2020). Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID‐19: A rapid review. Psychiatry Research, 292, Article 113307. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, E. , Sutin, A. R. , Daly, M. , & Jones, A. (2022). A systematic review and meta‐analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 296(1), 567–576. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, J. (2012). Great expectations: A systematic review of the literature on the role of family carers in severe mental illness, and their relationships and engagement with professionals. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(1), 70–82. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, S. M. , Jorm, A. F. , Toumbourou, J. W. , & Lubman, D. I. (2015). Parent and family factors associated with service use by young people with mental health problems: A systematic review. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 9(6), 433–446. 10.1111/eip.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D. T. L. (2002). Assessment of family functioning in Chinese adolescents: The Chinese family assessment instrument. International Perspectives on Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 2, 297–316. 10.1016/S1874-5911(02)80013-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D. T. L. , & Ma, C. M. S. (2010). The Chinese family assessment instrument (C‐FAI) hierarchical confirmatory factor analyses and factorial invariance. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(1), 112–123. 10.1177/1049731509355145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W. , & Hall, B. J. (2020). What can we do for people exposed to multiple traumatic events during the coronavirus pandemic? Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102065. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W. , & Hall, B. J. (2021). Help‐seeking intention among Chinese college students exposed to a natural disaster: An application of an extended theory of planned behavior (E‐TPB). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56, 1273–1282. 10.1007/s00127-020-01993-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W. , Shen, Z. , Wang, S. , & Hall, B. J. (2020). Barriers to professional mental health help‐seeking among Chinese adults: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, Article 442. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigal, J. , & Nally, M. (2004). Cultural perspectives on gender. In Paludi M. A. (Ed.), Praeger guide to the psychology of gender (pp. 27–40). Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L. , Wang, K. , Fan, F. , Su, Y. , & Gao, X. (2008). Reliability and validity of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED) in Chinese children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(4), 612–621. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam Ashing, K. , Padilla, G. , Tejero, J. , & Kagawa‐Singer, M. (2003). Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psycho‐Oncology, 12(1), 38–58. 10.1002/pon.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorisdottir, I. E. , Asgeirsdottir, B. B. , Kristjansson, A. L. , Valdimarsdottir, H. B. , Tolgyes, E. M. J. , Sigfusson, J. , … Halldorsdottir, T. (2021). Depressive symptoms, mental wellbeing, and substance use among adolescents before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Iceland: A longitudinal, population‐based study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(8), 663–672. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vai, B. , Mazza, M. G. , Delli Colli, C. , Foiselle, M. , Allen, B. , Benedetti, F. , … De Picker, L. J. (2021). Mental disorders and risk of COVID‐19‐related mortality, hospitalisation and intensive care unit admission: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Psychiatry, 8(9), 797–812. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00232-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zyl, L. E. , Rothmann, S. , & Zondervan‐Zwijnenburg, M. A. (2021). Longitudinal trajectories of study characteristics and mental health before and during the COVID‐19 lockdown. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 633533. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. , Su, L. Y. , Zhu, Y. , Zhai, J. , Yang, Z. W. , & Zhang, J. S. (2002). Norms of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders in Chinese urban children. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 10(4), 270–272. 10.1007/s11769-002-0042-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- William Li, H. C. , Chung, O. K. J. , & Ho, K. Y. (2010). Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Children: Psychometric testing of the Chinese version. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(11), 2582–2591. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You, J. , & Lu, Q. (2014). Sources of social support and adjustment among Chinese cancer survivors: Gender and age differences. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(3), 697–704. 10.1007/s00520-013-2024-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L. , Shek, D. T. L. , Zou, K. , Lei, Y. , & Jia, P. (2022). Cohort Profile: Chengdu Survey of Positive Child Development (CPCD) survey. International Journal of Epidemiology, 51(3), e95–e107. 10.1093/ije/dyab237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J. , Liu, L. , Xue, P. , Yang, X. , & Tang, X. (2020). Mental health response to the COVID‐19 outbreak in China. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(7), 574–575. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.‐J. , Zhang, L. G. , Wang, L. L. , Guo, Z. C. , Wang, J. Q. , Chen, J. C. , … Chen, J. X. (2020). Prevalence and socio‐demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID‐19. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(6), 749–758. 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]