Abstract

Aims and Objectives

To determine the frequency, timing, and duration of post‐acute sequelae of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (PASC) and their impact on health and function.

Background

Post‐acute sequelae of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is an emerging major public health problem that is poorly understood and has no current treatment or cure. PASC is a new syndrome that has yet to be fully clinically characterised.

Design

Descriptive cross‐sectional survey (n = 5163) was conducted from online COVID‐19 survivor support groups who reported symptoms for more than 21 days following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

Methods

Participants reported background demographics and the date and method of their covid diagnosis, as well as all symptoms experienced since onset of covid in terms of the symptom start date, duration, and Likert scales measuring three symptom‐specific health impacts: pain and discomfort, work impairment, and social impairment. Descriptive statistics and measures of central tendencies were computed for participant demographics and symptom data.

Results

Participants reported experiencing a mean of 21 symptoms (range 1–93); fatigue (79.0%), headache (55.3%), shortness of breath (55.3%) and difficulty concentrating (53.6%) were the most common. Symptoms often remitted and relapsed for extended periods of time (duration M = 112 days), longest lasting symptoms included the inability to exercise (M = 106.5 days), fatigue (M = 101.7 days) and difficulty concentrating, associated with memory impairment (M = 101.1 days). Participants reported extreme pressure at the base of the head, syncope, sharp or sudden chest pain, and “brain pressure” among the most distressing and impacting daily life.

Conclusions

Post‐acute sequelae of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection can be characterised by a wide range of symptoms, many of which cause moderate‐to‐severe distress and can hinder survivors' overall well‐being.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

This study advances our understanding of the symptoms of PASC and their health impacts.

Keywords: chronic disease, COVID‐19, symptom, symptom burden

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

This study advances clinical understanding of post‐acute sequelae of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (PASC) symptoms and their impact on human life.

This study enables nurses to better assist patients in recovery by identifying the range of PASC symptoms nurses can address through symptom management education and therapeutic communication.

This study identifies the most distressing PASC symptoms, helping clinicians to prioritise symptoms to be targeted immediately to improve quality of life for PASC patients.

1. INTRODUCTION

As of August 2021, SARS‐CoV‐2 has infected more than 214 million worldwide (Johns Hopkins University of Medicine, 2021). It is estimated that 10%–30% of persons who survive COVID‐19—including those with asymptomatic, mild and moderate infection—have persistent symptoms and do not fully recover or return to pre‐morbid functioning (Fernández‐de‐las‐Peñas et al., 2021; Mahase, 2020). The medical community only recently recognised post‐infectious persistent symptoms with a protracted recovery period as a new syndrome. Originally called long‐COVID or “long‐haul,” the NIH recently re‐named the condition as post‐acute sequelae of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (PASC). PASC has no effective treatment or cure, and the long‐term consequences and symptom duration of PASC remain unknown. More than a year into the COVID‐19 pandemic, survivors report persistent symptoms that have often remitted and relapsed. While it is too early to determine if PASC will eventually resolve or become a chronic condition, it is critical to characterise sequelae of this new syndrome.

Reports from PASC survivors may provide clues to inform treatment and management. Unfortunately, there are few arge studies that go beyond identification of symptoms (Carfi et al., 2020). Studies that use electronic health records likely provide accurate information about symptoms and their temporal order but are limited by completeness of all symptoms (Huang et al., 2021). Reports suggest that PASC survivors often do not disclose all symptoms to providers for fear of dismissal by clinicians and embarrassment (Fahmy, 2020). Further, it is well documented that during clinical visits to providers, patients in general tend to focus on the most bothersome symptoms (Li et al., 2019). These studies allude to the variability and complexity of symptom presentations of PASC. Comprehensive accounts, as reported by survivors of PASC, of detailed symptom onset, type, quality and duration are urgently needed to better understand PASC sequalae, its management, and strategies to improve function and quality of life. In this study, we report the patients' (n = 5163) account of number and temporal order of PASC symptoms, including median onset and duration of symptoms, and perceived distress and impact on their lives.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study sample

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Indiana University, and electronic informed consent was obtained from subjects prior to data collection. Data were collected from August 2020 to February 2021 from a convenience sample COVID‐19 survivors aged 18 or older. Participants were recruited from Survivor Corps, a Facebook community of more than 176,000 COVID‐19 survivors, and other online survivor communities. Inclusion criteria were (a) age 18 or older, (b) could read and respond in English and (c) COVID‐19 symptoms present for 21 days or longer. COVID‐19‐negative individuals were excluded. Participants completed an online symptom survey in REDCap.

2.2. Symptom survey

Symptoms were identified through content analysis of unstructured data, derived from publicly available health narrative data (unprompted posts on Facebook where COVID‐19 survivors described their symptoms). Symptoms listed in the survey were the patients' own words (e.g. “brain pressure” and “changes in hormones”). We opted to do this for two reasons. First, we wanted to ensure that survivors would recognise symptoms. Second, we were cautious to not improperly medicalize survivor symptoms without first validating that the medical terminology represented the symptom experience of survivors. Additionally, the survey asked about past medical history and their experiences seeking treatment for PASC.

For each symptom, a 5‐point Likert scale (from “Not at all” to “Very much”) was used to assess the degree to which each symptom caused pain and discomfort, work impairment and social relationship impact. The survey collected onset (date it started), duration (how many days), intensity (Likert scale) and burden (e.g. impact on life, Likert scale) of symptoms. It also captured whether symptoms were intermittent and whether they had resolved.

2.3. Data analysis

All survey data were manually reviewed for completeness and cleaned using a codebook before statistical analysis. The final dataset for analysis consisted of 5163 participants. Descriptive statistics and measures of central tendencies were computed for the following: percentage of participants who reported each symptom, the median time to symptom onset, median symptom duration was calculated for each symptom instead of averages due to the presence of several large outliers, and the percentage of participants reporting that a symptom was ongoing. The percentage of participants who reported any symptom as intermittent was calculated for each symptom. To assess the impact of each symptom on pain and discomfort, work impairment and social relationships, the average score from the 5‐point Likert scale was determined. The tidyverse R package was used to visualise the relationship between symptom discomfort and duration, the distribution of the number of symptoms reported by each participant, and to create a table containing all symptom metrics calculated for this study (Wickham et al., 2019). We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for reporting observational studies to report results (see checklist in Appendix S1; Von Elm et al., 2007).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Survey demographics

The overall response rate for completing the survey was 54%. Participants were predominantly White (81.3%), female (85.7%), never hospitalised for COVID‐19 (89.3%) and had RT‐PCR confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or were clinician diagnosed (77.1%). See Table 1 for more detail.

TABLE 1.

Participant demographics

| Characteristic | Participants (n = 5163), No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Race and ethnicity | |

| White | 4198 (81.3) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 330 (6.4) |

| Multiracial | 159 (3.1) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 114 (2.2) |

| Black | 111 (2.2) |

| Hispanic or Latinx, White | 89 (1.7) |

| Black | 41 (0.8) |

| American Indian | 35 (0.7) |

| Hispanic or Latinx, Multiracial | 27 (0.5) |

| Other | 22 (0.4) |

| Middle Eastern | 19 (0.4) |

| Hispanic or Latinx, American Indian | 7 (0.1) |

| Hispanic or Latinx, Black | 6 (0.1) |

| Hispanic or Latinx, Other | 3 (0.1) |

| Hispanic or Latinx, Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 (0.0) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 4422 (85.7) |

| Male | 714 (13.8) |

| Non‐binary/non‐conforming | 15 (0.3) |

| Unknown | 10 (0.2) |

| Transgender | 2 (0.0) |

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 118 (2.2) |

| 25–34 | 593 (11.5) |

| 35–44 | 1298 (25.1) |

| 45–54 | 1560 (30.2) |

| 55–64 | 1122 (21.7) |

| 65–74 | 428 (8.3) |

| 75–84 | 40 (0.8) |

| 85+ | 4 (0.1) |

| COVID‐19 diagnosis | |

| Positive COVID‐19 test | 2644 (51.2) |

| Diagnosis from doctor | 1337 (25.9) |

| Self‐diagnosed based on symptoms | 918 (17.8) |

| Other | 264 (5.1) |

| Hospitalised | |

| No | 4918 (83.9) |

| Yes | 876 (15.5) |

| NA | 38 (0.6) |

Note: Table showing distribution of participants based on race and ethnicity, gender, age, mode of determining SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, and hospitalisation status.

3.2. Prevalence, onset and duration of symptoms

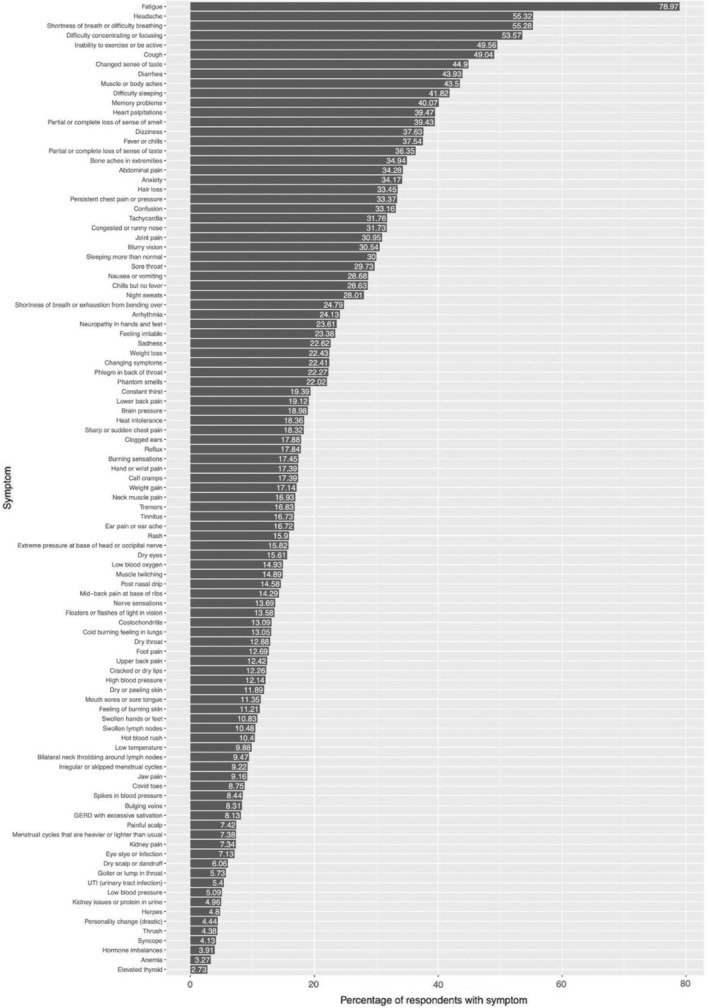

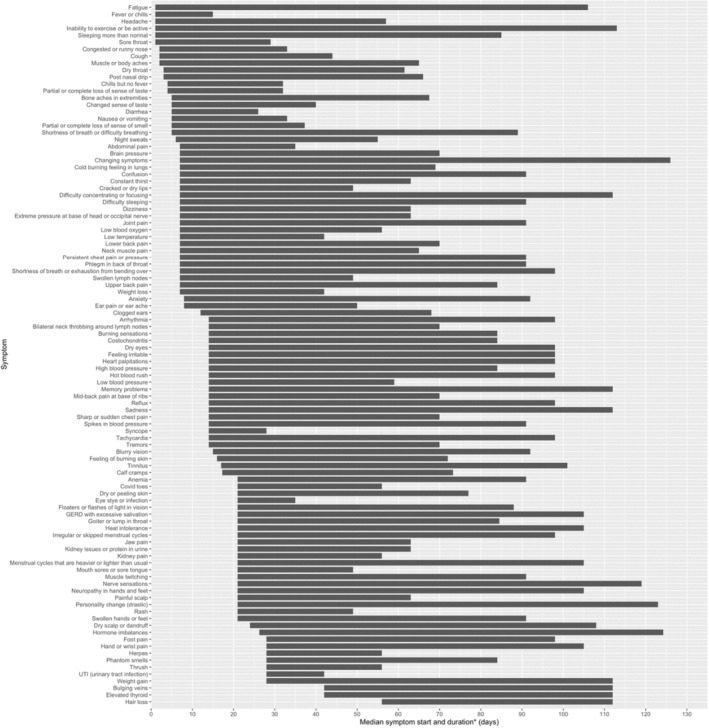

Participants reported a total of 101 symptoms. Not all participants had all symptoms. The mean number of symptoms experienced by any given participant was 21 with a range of 1–93 (Figure S1). The most common symptoms experienced included: fatigue, headache, shortness of breath, difficulty concentrating, inability to exercise, cough, change in sense of taste, diarrhoea, and muscle or body aches. The prevalence of symptoms is reported in Figure 1. Median onset and duration of PASC symptoms are reported in Figure 2. Visualisation of the symptom experience presented in Figure 2 illustrates the sequence and timing of symptoms suggesting a progression in symptomatology among individuals with PASC. For example, “flu‐like” symptoms (fatigue, fever/chills, headache, exercise intolerance, sleeping more than usual, sore throat, cough and upper respiratory congestion) were commonly associated with early or initial onset. A few days later, symptoms involving the neurological (“brain pressure,” difficulty concentrating, and anxiety), gastrointestinal (changes in sense of taste and smell, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea), and musculoskeletal systems (myalgias described as “lower back pain,” “upper back pain” and “neck muscle pain”), manifested. Much later in the course of the PASC symptom experience, symptoms associated with disturbances to the microvasculature, such as “Covid toes,” and integumentary, gynaecological and endocrine systems, resulted in reports of dry and peeling skin, changes in menstrual cycles, neuropathies, rashes, swelling of extremities, weight gain and hair loss.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of respondents reporting each COVID‐19 symptom. Graph showing percentage of participants (x‐axis) who experienced a given symptom (y‐axis).

FIGURE 2.

Median symptom onset and duration. Graph plotting the median time of symptom onset (in days after initial infection date) with median symptom duration. *Duration measures length of time the symptom was present and does not indicate resolution of the symptom. Participants noted these symptoms were ongoing at the time they completed the survey.

Symptom duration ranged from lasting from 2 weeks after symptom onset to over 100 days, with changing symptoms being a prominent, long‐lasting feature (Figure 2). For many symptoms, the onset and duration appeared to reflect an evolution of symptoms dominated by certain body systems. For example, early symptoms (arrhythmia to burning calves) with the same median symptom onset appeared to be heavily dominated by neurological and cardiovascular manifestations with some indicators of a strong immune response (enlarged and painful lymph nodes). This is then followed by symptoms suggestive of microvascular consequences (Covid toes) of infection, as well as changed in endocrine (thyroid) function. At the time of the survey, 98.0% of the respondents answered “Yes” to a question asking whether at least one of their symptoms was unresolved, and 97.8% answered “Yes” that at least one of their symptoms was intermittent, meaning it would temporarily remit and then later relapse. Collectively, these data illustrate a pattern of evolving symptoms experienced by persons with PASC.

3.3. Impact of symptoms on participants with PASC

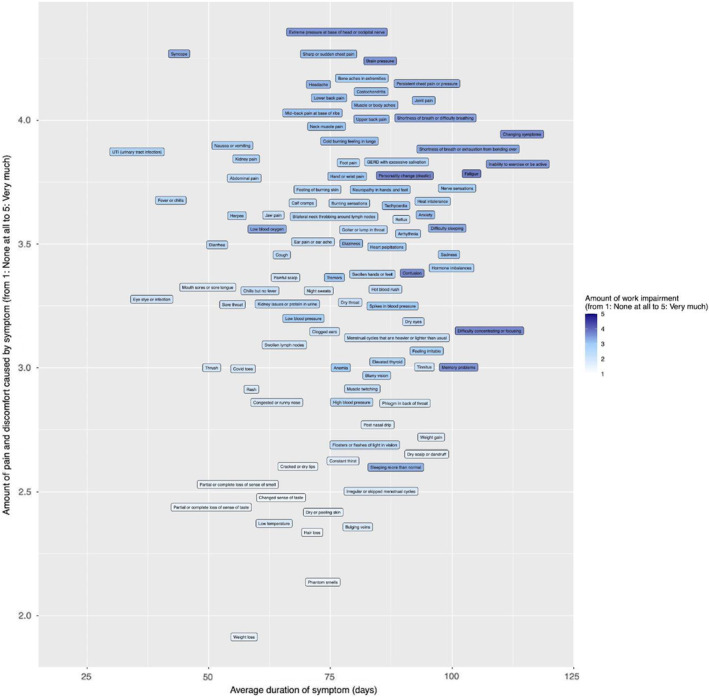

Subjects reported the time of diagnosis and mapped the onset and duration of symptoms. The calculations of average time to symptom onset; symptom duration; percentage of respondents who reported the symptom as intermittent or ongoing; and the average symptom impact in terms of pain and discomfort, work impairment and social relationship are recorded in Table 2. Variables included percentage reporting a symptom; pain and discomfort of the symptom (e.g. distress); ability to work or socialise; symptom duration; percentage reporting ongoing symptoms; and percentage reporting symptoms as intermittent. Potential morbidity, especially inability to work, was assessed through symptom severity, duration and perceived impact on ability to work (Figure 3). Symptoms perceived to have the most impact on ability to work included fatigue, personality change, a sensation of “brain pressure,” inability to sleep, inability to exercise, difficulty concentrating, memory problems, confusion, shortness of breath and the relapsing/remitting nature of symptoms.

TABLE 2.

COVID‐19 symptoms and their health impacts

| Symptom | Number of patients reporting symptom | Percentage of patients reporting symptom (%) | Median start date (days) | Median duration (days) | Average pain/discomfort of symptom (1–5) | Average work impairment of symptom (1–5) | Average social impairment of symptom (1–5) | Percentage afflicted reporting symptom as ongoing (%) | Percentage afflicted reporting symptom as intermittent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 4077 | 78.97 | 1 | 105 | 3.77 | 3.79 | 3.68 | 83.25 | 53.74 |

| Headache | 2856 | 55.32 | 1 | 56 | 4.15 | 3.22 | 3.07 | 65.90 | 76.68 |

| Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing | 2854 | 55.28 | 5 | 84 | 4.04 | 3.40 | 3.26 | 72.04 | 66.40 |

| Difficulty concentrating or focusing | 2766 | 53.57 | 7 | 105 | 3.14 | 3.66 | 3.18 | 83.41 | 69.99 |

| Inability to exercise or be active | 2559 | 49.56 | 1 | 112 | 3.84 | 3.48 | 3.60 | 84.25 | 32.00 |

| Cough | 2532 | 49.04 | 2 | 42 | 3.48 | 2.46 | 2.39 | 52.41 | 57.23 |

| Changed sense of taste | 2318 | 44.90 | 5 | 35 | 2.50 | 1.32 | 1.63 | 53.71 | 31.58 |

| Diarrhoea | 2268 | 43.93 | 5 | 21 | 3.50 | 2.49 | 2.39 | 44.22 | 63.62 |

| Muscle or body aches | 2246 | 43.50 | 2 | 63 | 4.05 | 3.12 | 2.98 | 64.07 | 61.62 |

| Difficulty sleeping | 2159 | 41.82 | 7 | 84 | 3.59 | 3.35 | 3.16 | 80.45 | 50.58 |

| Memory problems | 2069 | 40.07 | 14 | 98 | 3.00 | 3.55 | 3.10 | 86.52 | 63.80 |

| Heart palpitations | 2038 | 39.47 | 14 | 84 | 3.51 | 2.90 | 2.74 | 76.55 | 84.69 |

| Partial or complete loss of sense of smell | 2036 | 39.43 | 5 | 32.25 | 2.50 | 1.47 | 1.71 | 48.33 | 22.94 |

| Dizziness | 1943 | 37.63 | 7 | 56 | 3.53 | 3.14 | 2.92 | 68.76 | 82.86 |

| Fever or chills | 1938 | 37.54 | 1 | 14 | 3.68 | 2.60 | 2.47 | 27.19 | 57.28 |

| Partial or complete loss of sense of taste | 1877 | 36.35 | 4 | 28 | 2.46 | 1.44 | 1.71 | 45.07 | 24.08 |

| Bone aches in extremities | 1804 | 34.94 | 5 | 62.5 | 4.12 | 2.97 | 2.88 | 73.61 | 69.90 |

| Abdominal pain | 1770 | 34.28 | 7 | 28 | 3.77 | 2.47 | 2.56 | 61.07 | 80.51 |

| Anxiety | 1764 | 34.17 | 8 | 84 | 3.60 | 3.15 | 3.39 | 88.72 | 83.84 |

| Hair loss | 1727 | 33.45 | 56 | 56 | 2.34 | 1.40 | 1.74 | 76.03 | 15.98 |

| Persistent chest pain or pressure | 1723 | 33.37 | 7 | 84 | 4.12 | 3.30 | 3.15 | 66.69 | 67.38 |

| Confusion | 1712 | 33.16 | 7 | 84 | 3.38 | 3.65 | 3.33 | 78.62 | 77.10 |

| Tachycardia | 1640 | 31.76 | 14 | 84 | 3.62 | 3.09 | 2.94 | 70.49 | 76.77 |

| Congested or runny nose | 1638 | 31.73 | 2 | 31 | 2.86 | 1.89 | 1.83 | 57.39 | 53.79 |

| Joint pain | 1598 | 30.95 | 7 | 84 | 4.06 | 3.15 | 3.04 | 76.47 | 62.08 |

| Blurry vision | 1577 | 30.54 | 15 | 77 | 2.98 | 2.69 | 2.21 | 79.71 | 71.85 |

| Sleeping more than normal | 1549 | 30.00 | 1 | 84 | 2.63 | 3.25 | 3.16 | 68.82 | 38.80 |

| Sore throat | 1535 | 29.73 | 1 | 28 | 3.28 | 2.09 | 2.02 | 43.06 | 52.44 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 1481 | 28.68 | 5 | 28 | 3.88 | 2.84 | 2.77 | 45.78 | 70.02 |

| Chills but no fever | 1478 | 28.63 | 4 | 28 | 3.30 | 2.24 | 2.19 | 42.69 | 77.13 |

| Night sweats | 1446 | 28.01 | 6 | 49 | 3.29 | 1.93 | 1.88 | 49.03 | 69.16 |

| Shortness of breath or exhaustion from bending over | 1280 | 24.79 | 7 | 91 | 3.80 | 3.37 | 3.15 | 76.17 | 55.55 |

| Arrhythmia | 1246 | 24.13 | 14 | 84 | 3.53 | 2.84 | 2.77 | 79.86 | 87.72 |

| Neuropathy in hands and feet | 1219 | 23.61 | 21 | 84 | 3.71 | 3.04 | 2.86 | 79.66 | 68.33 |

| Feeling irritable | 1207 | 23.38 | 14 | 84 | 3.06 | 2.85 | 3.36 | 79.45 | 77.96 |

| Sadness | 1168 | 22.62 | 14 | 98 | 3.44 | 3.04 | 3.48 | 79.54 | 69.26 |

| Weight loss | 1158 | 22.43 | 7 | 35 | 1.91 | 1.55 | 1.53 | 36.01 | 18.05 |

| Changing symptoms | 1157 | 22.41 | 7 | 119 | 3.93 | 3.61 | 3.61 | 83.49 | 82.45 |

| Phlegm in back of throat | 1150 | 22.27 | 7 | 84 | 2.86 | 1.90 | 1.85 | 71.83 | 54.87 |

| Phantom smells | 1137 | 22.02 | 28 | 56 | 2.14 | 1.43 | 1.54 | 64.82 | 81.71 |

| Constant thirst | 1001 | 19.39 | 7 | 56 | 2.63 | 1.74 | 1.66 | 67.43 | 43.96 |

| Lower back pain | 987 | 19.12 | 7 | 63 | 4.10 | 3.17 | 2.99 | 65.96 | 63.32 |

| Brain pressure | 980 | 18.98 | 7 | 63 | 4.22 | 3.56 | 3.42 | 73.16 | 78.27 |

| Heat intolerance | 948 | 18.36 | 21 | 84 | 3.70 | 2.83 | 3.03 | 83.23 | 51.58 |

| Sharp or sudden chest pain | 946 | 18.32 | 14 | 56 | 4.25 | 3.15 | 2.95 | 59.83 | 79.49 |

| Clogged ears | 923 | 17.88 | 12 | 56 | 3.12 | 2.19 | 2.17 | 70.21 | 63.06 |

| Reflux | 921 | 17.84 | 14 | 84 | 3.56 | 2.23 | 2.23 | 73.07 | 72.42 |

| Burning sensations | 901 | 17.45 | 14 | 70 | 3.71 | 2.64 | 2.58 | 70.26 | 81.69 |

| Calf cramps | 898 | 17.39 | 17.25 | 56 | 3.69 | 2.37 | 2.28 | 71.38 | 84.97 |

| Hand or wrist pain | 898 | 17.39 | 28 | 77 | 3.78 | 3.05 | 2.47 | 77.17 | 67.37 |

| Weight gain | 885 | 17.14 | 28 | 84 | 2.72 | 1.81 | 2.11 | 82.94 | 15.14 |

| Neck muscle pain | 874 | 16.93 | 7 | 58 | 4.00 | 3.07 | 2.85 | 66.48 | 58.81 |

| Tremors | 869 | 16.83 | 14 | 56 | 3.35 | 3.05 | 2.75 | 66.28 | 76.18 |

| Tinnitus | 864 | 16.73 | 17 | 84 | 3.01 | 2.13 | 2.08 | 75.35 | 60.19 |

| Ear pain or ear ache | 863 | 16.72 | 8 | 42 | 3.51 | 2.35 | 2.23 | 58.98 | 69.06 |

| Rash | 821 | 15.90 | 21 | 28 | 2.91 | 1.84 | 1.87 | 46.41 | 46.04 |

| Extreme pressure at base of head or occipital nerve | 817 | 15.82 | 7 | 56 | 4.36 | 3.51 | 3.32 | 66.10 | 71.73 |

| Dry eyes | 806 | 15.61 | 14 | 84 | 3.16 | 2.32 | 1.99 | 74.81 | 54.59 |

| Low blood oxygen | 771 | 14.93 | 7 | 49 | 3.61 | 3.30 | 3.18 | 54.22 | 58.75 |

| Muscle twitching | 769 | 14.89 | 21 | 70 | 2.92 | 2.32 | 2.21 | 68.14 | 79.32 |

| Post nasal drip | 753 | 14.58 | 3 | 63 | 2.77 | 1.80 | 1.75 | 67.60 | 53.25 |

| Mid‐back pain at base of ribs | 738 | 14.29 | 14 | 56 | 4.05 | 3.09 | 2.91 | 63.01 | 63.96 |

| Nerve sensations | 707 | 13.69 | 21 | 98 | 3.72 | 2.89 | 2.81 | 76.38 | 74.82 |

| Floaters or flashes of light in vision | 701 | 13.58 | 21 | 67 | 2.67 | 2.38 | 2.06 | 74.04 | 72.18 |

| Costochondritis | 676 | 13.09 | 14 | 70 | 4.11 | 3.10 | 2.93 | 67.01 | 60.06 |

| Cold burning feeling in lungs | 674 | 13.05 | 7 | 62 | 3.93 | 3.13 | 3.07 | 64.39 | 70.62 |

| Dry throat | 665 | 12.88 | 3 | 58.5 | 3.26 | 2.24 | 2.14 | 68.42 | 58.80 |

| Foot pain | 655 | 12.69 | 28 | 70 | 3.80 | 2.72 | 2.62 | 80.61 | 68.09 |

| Upper back pain | 641 | 12.42 | 7 | 77 | 4.03 | 3.17 | 3.02 | 69.11 | 62.25 |

| Cracked or dry lips | 633 | 12.26 | 7 | 42 | 2.60 | 1.46 | 1.46 | 60.98 | 36.02 |

| High blood pressure | 627 | 12.14 | 14 | 70 | 2.89 | 2.55 | 2.41 | 68.58 | 55.34 |

| Dry or peeling skin | 614 | 11.89 | 21 | 56 | 2.42 | 1.56 | 1.55 | 66.61 | 29.97 |

| Mouth sores or sore tongue | 586 | 11.35 | 21 | 28 | 3.30 | 1.84 | 1.85 | 46.93 | 47.10 |

| Feeling of burning skin | 579 | 11.21 | 16 | 56 | 3.69 | 2.59 | 2.49 | 60.28 | 72.54 |

| Swollen hands or feet | 559 | 10.83 | 21 | 70 | 3.35 | 2.62 | 2.40 | 73.35 | 63.69 |

| Swollen lymph nodes | 541 | 10.48 | 7 | 42 | 3.12 | 2.07 | 1.98 | 52.87 | 43.81 |

| Hot blood rush | 537 | 10.40 | 14 | 84 | 3.34 | 2.38 | 2.36 | 70.02 | 80.63 |

| Low temperature | 510 | 9.88 | 7 | 35 | 2.39 | 1.82 | 1.87 | 53.33 | 68.63 |

| Bilateral neck throbbing around lymph nodes | 489 | 9.47 | 14 | 56 | 3.66 | 2.58 | 2.54 | 68.92 | 74.03 |

| Irregular or skipped menstrual cycles | 476 | 9.22 | 21 | 77 | 2.50 | 1.79 | 1.84 | 66.39 | 42.44 |

| Jaw pain | 473 | 9.16 | 21 | 42 | 3.63 | 2.30 | 2.20 | 58.14 | 67.23 |

| Covid toes | 452 | 8.75 | 21 | 35 | 3.00 | 1.96 | 1.85 | 50.00 | 44.91 |

| Spikes in blood pressure | 436 | 8.44 | 14 | 77 | 3.25 | 2.98 | 2.76 | 63.53 | 74.77 |

| Bulging veins | 429 | 8.31 | 42 | 70 | 2.36 | 1.84 | 1.75 | 73.43 | 62.00 |

| GERD with excessive salivation | 420 | 8.13 | 21 | 84 | 3.80 | 2.68 | 2.70 | 77.38 | 65.48 |

| Painful scalp | 383 | 7.42 | 21 | 42 | 3.35 | 2.04 | 2.02 | 54.57 | 57.96 |

| Menstrual cycles that are heavier or lighter than usual | 381 | 7.38 | 21 | 84 | 3.09 | 2.22 | 2.24 | 69.55 | 44.88 |

| Kidney pain | 379 | 7.34 | 21 | 35 | 3.86 | 2.74 | 2.60 | 49.34 | 67.28 |

| Eye stye or infection | 368 | 7.13 | 21 | 14 | 3.28 | 2.12 | 1.93 | 33.70 | 32.61 |

| Dry scalp or dandruff | 313 | 6.06 | 24 | 84 | 2.64 | 1.56 | 1.71 | 79.23 | 28.75 |

| Goitre or lump in throat | 296 | 5.73 | 21 | 63.5 | 3.57 | 2.45 | 2.37 | 65.54 | 50.68 |

| UTI (urinary tract infection) | 279 | 5.40 | 28 | 14 | 3.87 | 2.75 | 2.74 | 31.54 | 38.71 |

| Low blood pressure | 263 | 5.09 | 14 | 45 | 3.21 | 2.92 | 2.77 | 61.22 | 59.70 |

| Kidney issues or protein in urine | 256 | 4.96 | 21 | 42 | 3.28 | 2.58 | 2.51 | 58.59 | 37.89 |

| Herpes | 248 | 4.80 | 28 | 28 | 3.60 | 2.71 | 2.68 | 52.82 | 50.40 |

| Personality change (drastic) | 229 | 4.44 | 21 | 102 | 3.78 | 3.69 | 3.98 | 68.12 | 48.91 |

| Thrush | 226 | 4.38 | 28 | 28 | 3.00 | 1.95 | 2.05 | 33.63 | 30.09 |

| Syncope | 213 | 4.13 | 14 | 14 | 4.27 | 3.29 | 3.15 | 38.03 | 62.44 |

| Hormone imbalances | 202 | 3.91 | 26.25 | 98 | 3.42 | 2.82 | 2.88 | 68.32 | 45.54 |

| Anaemia | 169 | 3.27 | 21 | 70 | 3.00 | 3.01 | 2.90 | 73.96 | 23.67 |

| Elevated thyroid | 141 | 2.73 | 42 | 70 | 3.02 | 2.67 | 2.52 | 68.79 | 17.73 |

Note: Health impact variables include: percentage of participants reporting symptoms, pain and discomfort (e.g. level of distress), ability to work, social impairment, symptom duration, percentage reporting symptoms as ongoing, and percentage reporting symptoms as intermittent.

FIGURE 3.

Impact of level of distress and duration of symptoms on ability to work among PASC survivors. Graph showing the effect of duration of symptoms (x‐axis) and level of distress (y‐axis) on ability to work. Darker shades indicate greater impact on ability to work.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Our study findings provide a rather comprehensive patient reported list of symptoms that was generated by their narrative report, and then further validated in a larger population. On average, subjects reported 21 symptoms with the average time from initial diagnosis being 20.88 days. When symptoms were mapped for their average time of onset and duration, visualisation of these data from a large group of survivors showed a relatively predictable pattern of onset and duration, resembling a gradually increasing progression of symptoms over time. This indicates that there may be a pattern of progression of symptoms of PASC, beginning with flu‐like symptoms and progressing onwards through other major body systems. Additionally, almost all subjects who completed the survey reported persistent symptoms at 21 or more days. These findings warrant additional discussion, investigation and context within the current knowledge of PASC.

Our data suggest that the patient with PASC has a heavy symptom burden (average of 21 symptoms) and that the symptom experience is more long‐lasting than is currently captured by most research studies (Stavem et al., 2021; Tenforde et al., 2020). The study's ability to detect a larger number of symptoms can be attributed to including a list of potential COVID‐19 symptoms based on initial open‐ended research of the range of COVID‐19 sequelae conducted in July of 2020 and expanded through feedback on the survey design from Survivor Corps (Lambert & Survivor Corps, 2020). The high number of reported symptoms included in this study should assist nurses in remaining cognizant of patient complaints, and to maintain understanding that PASC can manifest in a wide array of nonspecific complaints that can cause debilitating impacts on an individual's daily life.

Similar to other work, we found that PASC was present in both hospitalised and non‐hospitalised survivors (Carfi et al., 2020). The majority of participants in our study were not hospitalised. Approximately 77% of participants reported clinician diagnosis or confirmed RT‐PCR for SARS‐CoV‐2, with 5% reporting “other” and 18% self‐diagnosing. Those without confirmed diagnosis may have attributed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection to a confirmed antibody test that was available early in the pandemic or through the presence of COVID‐specific symptoms such as loss of sense of smell. While there may be an inclination for researchers to exclude participants who do not have a positive RT‐PCR or antibody test, capturing the experiences of the earliest long haulers (before validated tests had become available) is essential for understanding the trajectory of PASC. Therefore, information obtained from PCR‐positive cohorts likely lags around 3–6 months behind persons who were infected early in the pandemic.

Post‐acute sequelae of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection impacted participants who are in the middle years of life represented 77% of our participants (n = 3980), aged 35–64. The number of women who participated in this study exceeded men. It not clear if the difference in gender reflects differences in prevalence or willingness to engage in research. Other studies also suggest that PASC occurs more frequently in women with an age distribution similar to this study, and future research should aim to validate the demographics most at risk for PASC (Sigfrid et al., 2021; Torjesen, 2021).

Participants reported multiple symptoms that when visualised by average onset and duration of specific symptoms appeared to cluster together. This observation is consistent with other reports, including of hospitalised individuals (Carfi et al., 2020). The temporal nature of these symptoms may provide clues into underlying pathogenesis, which is currently unclear. Others describe PASC symptoms, which may indicate an evolving process guided by endothelial dysfunction, immune‐mediated inflammation, oxidative stress and hormonal imbalance (Leung et al., 2020; Theoharides & Conti, 2020). However, a causal relationship has not been established. These findings align with Huang et al. (2021)'s study of medically documented symptoms from an EHR data set that took a conservative approach with documenting symptom type (only new symptoms at 0–11 days) and establishing the temporal order of symptoms (starting 60 days after a positive SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR test). We also report the same symptoms as Huang et al. (2021) in which they identified five symptom clusters among non‐hospitalised PASC survivors, and the dominant symptoms in those clusters all represented in the top quartile of symptoms reported here. While additional work is needed to validate symptom clusters by time, our findings are consistent with initial evidence of symptom clustering in other work using other datasets and point to consistent pattern of findings. Of note is the changing nature of symptoms, which appears to be a particularly distressing feature among PASC survivors.

Finally, PASC appears to exert variable degrees of impact on individuals such as their ability to work, but mechanistic insight is lacking. Most studies to date have focused on hospitalised patients; however, in our study most participants were never hospitalised, suggesting that PASC has profound effects, independent of COVID‐19 severity. Factors that were reported to have the most impact on participants' ability to work after developing PASC included the relapsing and remitting nature of symptoms, the long duration of many symptoms reported as unresolved, as well as fatigue and symptoms associated with altered cognition or memory impairment. Overall, reported symptoms varied with regards to duration and for their degree of distress, suggesting that a symptom of PASC can cause severe health impact for some and milder impact for others, making PASC an experience that is unique to the individual. Considering the great number and severity of health impacts caused by PASC, future research with PASC patients should endeavour to collect qualitative data characterising the lasting impact on ability to work, maintain social relationships, mental health, as well as basic everyday functioning. Future research could advance the science by examining cluster specific symptoms based on expected timing of onset and grouping symptom clusters by demographics.

The strengths of this study include development of a comprehensive tool for unstructured patient data, beginning with confirmation that these symptoms represented PASC, among the 5163 individuals who have and are continuing to experience symptoms up to a year after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (PASC survivors). Participants were able to describe their symptoms and health impact caused by these symptoms in detail, which provides additional richness and insight into symptom sequelae.

There are several limitations of this study, but within the context to what little is known about PASC, we hope this work will be foundation for larger scale studies that rely less on patient recall for data collection. Additional limitations are patient recall of illness and varying times from time of initial diagnosis in which patients completed the survey. Sampling was by convenience, non‐probability. It is difficult to determine if study participants were representative of PASC as it occurs in the general population or if these data are representative of survivors most engaged in advocacy and support. Further, generalizability of the findings is limited based on demographics; the sample population was predominantly white, female and non‐hospitalised.

5. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

The post‐acute sequelae of SARS‐CoV‐2 (PASC) infection has emerged as a major public health problem. PASC is poorly understood. However, it is clear that PASC does not discriminate and can affect those who were never hospitalised for severe illness. This study provides data on a national sample of 5163 individuals who have and continue to experience symptoms up to a year after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. This study advances clinical understanding of PASC symptoms and their impact on human life. Because nurses are experts in symptom management and there is no cure or treatment for PASC, nurse clinicians and researchers play a critical role in helping patients to recover through symptom management and therapeutic communication. Nurses are able to assist patients in managing symptoms using established strategies; nurse scientist can help patients more quickly move towards recovery by leveraging our self‐management intervention evidence base and retooling or repurposing our already packaged symptom management interventions for PASC patients (Pinto et al., 2021). Additionally, nurses may assist patients in recovery by helping them manage illness‐related health impacts through education and therapeutic communication, including validation of the patient's PASC symptom experience (Pinto et al., 2021). This is of particular importance for patients with this new disease; knowledge is limited and patients have experienced medical gaslighting and trauma when they have sought care for PASC (Pinto et al., 2021). Validating these unpleasant and often traumatising experiences with providers can help restore patient trust and prevent re‐traumatization, ultimately increasing better outcomes for PASC patients and increasing the potential for their reengagement with the larger healthcare system (Pinto et al., 2021). In summary, the most distressing symptoms could be addressed by nursing practice and science, and thereby can be targeted immediately for treatment to improve functioning, chance of recovery and quality of life for PASC patients.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Survivor Corps for mobilising many thousands of COVID‐19 survivors to participate in research to find a cure for COVID‐19, and for being the epicentre of hope for so many. We would like to express our deep gratitude to the thousands of long haulers who spent many hours taking this survey while suffering from the impacts of PASC. The answers we need to cure PASC will come from listening and learning from those who suffer from the disease. We would also like to thank the Precision Health Initiative at Indiana University for their support on this project.

Lambert, N. ; Survivor Corps , El‐Azab, S. A. , Ramrakhiani, N. S. , Barisano, A. , Yu, L. , Taylor, K. , Esperança, Á. , Mendiola, C. , Downs, C. A. , Abrahim, H. L. , Hughes, T. , Rahmani, A. M. , Borelli, J. L. , Chakraborty, R. , & Pinto, M. D. (2022). The other COVID‐19 survivors: Timing, duration, and health impact of post‐acute sequelae of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 00, 1–13. 10.1111/jocn.16541

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Carfi, A. , Bernabei, R. , & Landi, F. (2020). Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID‐19. JAMA Network Open, 324(6), 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy, A. (2020). Women with chronic COVID‐19 struggle to be heard by doctors . Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/female‐covid‐19‐long‐haulers‐doctors‐dismiss‐symptoms‐5075224

- Fernández‐de‐las‐Peñas, C. , Palacios‐Ceña, D. , Gómez‐Mayordomo, V. , Cuadrado, M. L. , & Florencio, L. L. (2021). Defining post‐COVID symptoms (post‐acute COVID, long COVID, persistent post‐COVID): An integrative classification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2621. 10.3390/ijerph18052621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. , Pinto, M. D. , Borelli, J. L. , Mehrabadi, M. A. , Abrihim, H. , Dutt, N. , Lambert, N. , Nurmi, E. L. , Chakraborty, R. , Rahmani, A. M. , & Downs, C. A. (2021). COVID symptoms, symptom clusters, and predictors for becoming a long‐hauler: Looking for clarity in the haze of the pandemic. medRxiv, 2021.03.03.21252086. 10.1101/2021.03.03.21252086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins University of Medicine . (2021). COVID‐19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) . https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- Lambert, N. , & Survivor Corps . (2020). COVID‐19 “long hauler” symptoms survey report . https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e8b5f63562c031c16e36a93/t/5f459ef7798e8b6037fa6c57/1598398215120/2020+Survivor+Corps+COVID‐19+%27Long+Hauler%27+Symptoms+Survey+Report+%28revised+July+25.4%29.pdf

- Leung, T. Y. M. , Chan, A. Y. L. , Chan, E. W. , Chan, V. K. Y. , Chui, C. S. L. , Cowling, B. J. , Gao, L. , Ge, M. Q. , Hung, I. F. N. , Ip, M. S. M. , Ip, P. , Lau, K. K. , Lau, C. S. , Lau, L. K. W. , Leung, W. K. , Li, X. , Luo, H. , Man, K. K. C. , Ng, V. W. S. , … Wong, I. C. K. (2020). Short‐ and potential long‐term adverse health outcomes of COVID‐19: A rapid review. Emerging Microbes & Infections, 9(1), 2190–2199. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1825914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, B. , Mah, K. , Swami, N. , Pope, A. , Hannon, B. , Lo, C. , Rodin, G. , Le, L. W. , & Zimmermann, C. (2019). Symptom assessment in patients with advanced cancer: Are the most severe symptoms the most bothersome? Journal of Palliative Medicine, 22(10), 1252–1259. 10.1089/jpm.2018.0622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahase, E. (2020). Covid‐19: What do we know about “long covid”? BMJ, 370, m2815. 10.1136/bmj.m2815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, M. D. , Downs, C. A. , Lambert, N. , & Burton, C. W. (2021). How an effective response to post‐acute sequelae of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (PASC) relies on nursing research. Research in Nursing & Health, 44(5), 743–745. 10.1002/nur.22176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigfrid, L. , Drake, T. M. , Pauley, E. , Jesudason, E. C. , Olliaro, P. , Lim, W. S. , Gillesen, A. , Berry, C. , Lowe, D. J. , McPeake, J. , Lone, N. , Cevik, M. , Munblit, D. J. , Casey, A. , Bannister, P. , Russell, C. D. , Goodwin, L. , Ho, A. , Turtle, L. , … ISARIC4C Investigators . (2021). Long Covid in adults discharged from UK hospitals after Covid‐19: A prospective, multicentre cohort study using the ISARIC WHO clinical characterisation protocol. medRxiv, 2021.03.18.21253888. 10.1101/2021.03.18.21253888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavem, K. , Ghanima, W. , Olsen, M. K. , Gilboe, H. M. , & Einvik, G. (2021). Persistent symptoms 1.5–6 months after COVID‐19 in non‐hospitalised subjects: A population‐based cohort study. Thorax, 76(4), 405–407. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenforde, M. W. , Kim, S. S. , Lindsell, C. J. , Billig Rose, E. , Shapiro, N. I. , Files, D. C. , Gibbs, K. W. , Erickson, H. L. , Steingrub, J. S. , Smithline, H. A. , Gong, M. N. , Aboodi, M. S. , Exline, M. C. , Henning, D. J. , Wilson, J. G. , Khan, A. , Qadir, N. , Brown, S. M. , Peltan, I. D. , … Wu, M. J. (2020). Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID‐19 in a multistate health care systems network—United States, March–June 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(30), 993–998. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides, T. C. , & Conti, P. (2020). COVID‐19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome, or is it mast cell activation syndrome? Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents, 34(5), 1633–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torjesen, I. (2021). Covid‐19: Middle aged women face greater risk of debilitating long term symptoms. BMJ, 372, n829. 10.1136/bmj.n829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm, E. , Altman, D. G. , Egger, M. , Pocock, S. J. , Gøtzsche, P. C. , & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2007). Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ, 335(7624), 806–808. 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. , Averick, M. , Bryan, J. , Chang, W. , McGowan, L. D. , François, R. , Grolemund, G. , Hayes, A. , Henry, L. , Hester, J. , Kuhn, M. , Pedersen, T. L. , Miller, E. , Bache, S. M. , Müller, K. , Ooms, J. , Robinson, D. , Seidel, D. P. , Spinu, V. , … Yutani, H. (2019). Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43), 1686. 10.21105/joss.01686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1

Appendix S1

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.