To the Editor,

Hong Kong's Vaccine Allergy Safety (VAS) guidelines were established to address concerns regarding COVID‐19 vaccine‐related allergic reactions, with a dedicated population‐wide VAS‐Track Pathway established since early 2021. 1 , 2 Two types of patients were assessed: ‘Pre‐Vaccine’ (vaccine‐naive) individuals with history of anaphylaxis, or severe and immediate‐type reactions to multiple classes of drugs (assessed for potential excipient allergies—prior to updated guidelines in late 2021); and ‘Post‐Vaccine’ patients with history of suspected hypersensitivity reactions following prior COVID‐19 vaccination. All patients gave consent. Suspected allergies were assessed by Allergists to differentiate from reactogenic symptoms. Allergy was confidently excluded or confirmed by vaccine provocation tests. Remaining patients with clinical histories compatible with vaccine‐associated allergy but declined provocation tests were labelled with ‘possible’ allergy. The VAS Clinics noticed an obvious imbalance in sex ratio, with many more females referred for pre‐ and post‐vaccination concerns. Approved by the HKU/HA HKW Institutional Review Board, this study was performed to confirm and investigate into possible causes of this phenomenon.

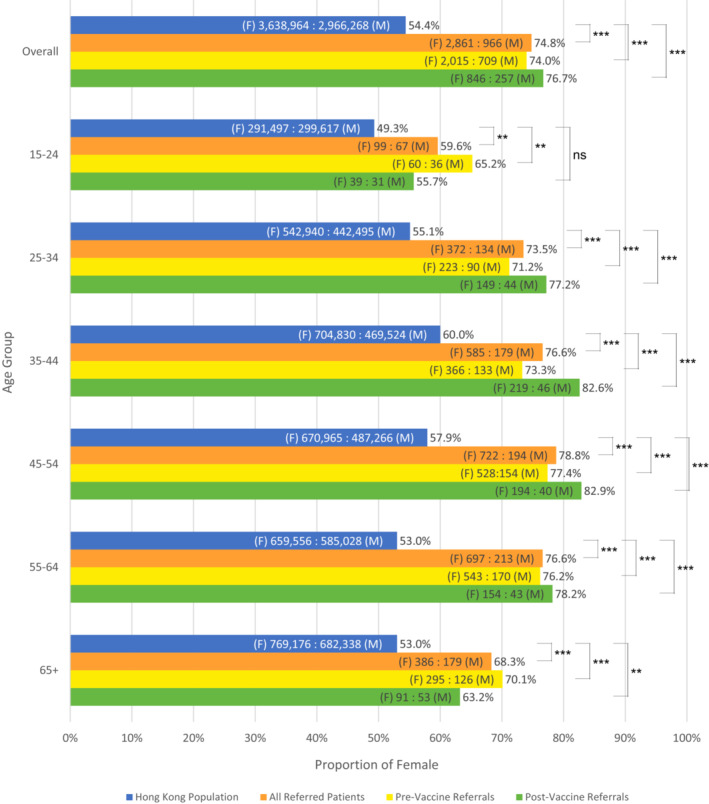

We compared the female‐to‐male ratio of 3201 consecutive patients referred to VAS‐Track Pathway to Hong Kong's Population Census Data using the binomial test. There was a significantly higher proportion of female referrals (74.8% vs. 54.4%, p < .001). The female‐skewed ratios remained significant across all age groups, as well as indications for referral (pre‐ or post‐vaccine; Figure 1). Despite the higher proportion of female referrals, there were no significant difference in sex among patients with COVID‐19 vaccine‐associated allergy across all age groups (Table 1). We postulated that the skewed sex ratio may be due to higher prevalence of urticaria among female patients. In view of this, we performed subgroup analysis by excluding patients with any history of urticaria, which did not impact our findings with a female:male ratio of 77.0% (vs. 54.4% of the general population, p < .001).

FIGURE 1.

Female‐to‐male ratio in census data compared with VAS‐Track referrals across age groups. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; ns, not significant. F, female; M, male

TABLE 1.

Rate of confirmed or possible allergy to COVID‐19 vaccination after Allergist assessment by sex

| Parameters |

All (N = 3201) |

Male (N = 816) |

Female (N = 2385) |

p‐value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed or possible allergy b :Recommended for vaccination (% allergy) | ||||

| Age group | ||||

| Overall | 403:2798 (12.6%) | 91:725 (11.2%) | 312:2073 (13.1%) | .151 |

| 15–24 | 10:107 (8.5%) | 3:46 (6.1%) | 7:61 (10.3%) | .517 |

| 25–34 | 53:349 (13.2%) | 13:97 (11.8%) | 40:252 (13.7%) | .619 |

| 35–44 | 74:552 (11.8%) | 15:139 (9.7%) | 59:413 (12.5%) | .357 |

| 45–54 | 92:704 (11.6%) | 20:154 (11.5%) | 72:550 (11.6%) | .976 |

| 55–64 | 117:672 (14.8%) | 23:163 (12.4%) | 94:509 (15.6%) | .280 |

| 65+ | 57:414 (12.1%) | 17:126 (11.9%) | 40:288 (12.2%) | .925 |

Chi‐square test.

Patients with histories compatible with vaccine‐associated allergy and could not be excluded (i.e., declined vaccine provocation tests).

We are the first to report a discrepancy of female referrals for suspected COVID‐19 vaccine allergic reactions, although there was no difference in sex among patients subsequently recommended for vaccination. Differences in immunogenic and reactogenic responses to vaccines and drugs are well documented, with females often reporting more frequent and severe reactions. 3 , 4 Postulated mechanisms for differences observed are multifactorial and can be divided into aspects relating to sex, gender and comorbidities.

Biological sex contributes to physical and physiological differences that may affect the rate of reactogenic symptoms. Females generally have lower body weights and body surface areas; leading to higher blood drug concentrations, longer elimination times and possible augmented reactogenicity. 5 Physiologically, immune responses are stronger in females, with hormones playing a pivotal role. Differences in genetic factors linked to the X‐chromosome, epigenetics and microbiota have also been postulated to affect immunoregulation. 4

Gender reflects behaviours that are shaped by psychological, social and cultural influences. They affect the perceptions, experiences and subsequent management of vaccine reactions. Cultural environments that selectively emphasize the importance of outer appearance for women, can lead to females having lower symptom tolerance, especially with mucocutaneous manifestations. Symptoms visible on the face or body, albeit mild, can more easily become a source of psychological stress and anxiety. Women are also more proactive in health information‐seeking, as reflected by higher consulting rates in general practice. 6 However, this might also infer that they are more susceptible to misinformation and subsequent misdiagnoses of vaccine reactions.

Finally, comorbidities could have confounding impact on drug and vaccine reactions. Although we excluded urticaria as a possible confounder, atopic dermatitis and asthma are also more prevalent among females, which may be misdiagnosed as vaccine allergies during coincidental flares. 3

Whether reactions are reactogenic (non‐vaccine‐specific and attributed to immunogenicity of vaccination) or allergic (genuine hypersensitivity to a vaccine‐specific component) in nature are difficult to discern, and there is likely a degree of both at play. Suspected allergies were assessed to differentiate from reactogenic symptoms by thorough clinical history taking, including symptom manifestation, temporal relationship between vaccination and symptom onset, as well as characterization of mucocutaneous symptoms. For more challenging cases, vaccine provocation tests were performed to exclude genuine vaccine allergy. Interestingly, genuine COVID‐19 vaccine‐related allergy remains extremely rare and there was no obvious difference observed between both sexes regarding vaccination outcomes. Limitations include incomplete workup for patients with ‘possible allergy’ as well as sample size and age of patients. Patients with clinical histories suggestive of allergy but declined provocation tests were diagnosed as ‘possible allergy’, which likely grossly over‐estimates the incidence of genuine allergy. Sex differences in immunity are usually only obvious after puberty; our study only included adults and whether our findings are reflected in paediatric populations cannot be extrapolated. Further studies on the reasons for higher rate of suspected vaccine allergic reactions among females are warranted.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund (HMRF) grant, Ref: COVID‐1903011.

Valerie Chiang and Andy Ka Chun Kan contributed equally to this work and should be considered joint first author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chiang V, Saha C, Yim J, et al. The Role of the allergist in coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine allergy safety: a pilot study on a "hub‐and‐spoke" model for population‐wide allergy service. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129(3):308–312.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chiang V, Leung ASY, Au EYL, et al. Updated consensus statements on COVID‐19 vaccine allergy safety in Hong Kong. Asia Pac Allergy. 2022;12(1):e8. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2022.12.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Martinis M, Sirufo MM, Suppa M, Di Silvestre D, Ginaldi L. Sex and gender aspects for patient stratification in allergy prevention and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1535. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(10):626‐638. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zucker I, Prendergast BJ. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics predict adverse drug reactions in women. Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00308-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Vries ST, Denig P, Ekhart C, et al. Sex differences in adverse drug reactions reported to the National Pharmacovigilance Centre in The Netherlands: an explorative observational study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(7):1507‐1515. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]