Morbidity and mortality from SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in heart (HT) and lung transplant (LT) recipients are high, especially for LT recipients, despite vaccination. 1 Despite severe COVID‐19 outcomes, HT/LT recipients represent <10% of solid organ transplant recipients (SOTRs) included in cohort studies evaluating two and three dose regimens. 2 There is now strong evidence to support that SOTRs in a greater immunosuppressed state (common among HT/LT recipients) are at increased risk for persistent seronegative state post‐D3. 3 , 4 Therefore, we evaluated antispike antibody responses before and after a third vaccine dose (D3) in HT/LT recipients to quantify post‐D3 antibody responses.

One hundred and thirty‐two HT and 91 LT recipients were prospectively recruited to our national observational study of vaccine outcomes in SOTRs. Demographics, transplant type and date, vaccine type and date, and immunosuppression medications were collected via patient report. Inclusion criteria included: English‐speaking, age ≥18 years, having ≥1 pre‐D3 antibody measurement, and no reported prior SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Exclusion criteria included missing data on medications, combined HT–LT and/or kidney transplant status (n = 4), and belatacept use (n = 2).

Serologic antibody testing was performed on two commercial assays; the Roche Elecsys anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor‐binding domain (RBD) assay (range: .799–2500 U/ml, positive ≥ .8 U/ml per manufacturer) or the EUROIMMUN antispike (S1) assay (range: .1–8.94 arbitrary units (AU), positive ≥ 1.1 AU per manufacturer). Categories of positive response were further characterized based on published data in SOTRs: (i) ≥250U/ml or ≥4 AU (consistent with potential neutralization of ancestral SARS‐CoV‐2 variants, i.e., “low‐titer”), or (ii) ≥2500 U/ml or ≥8 AU (consistent with potential neutralization of Omicron sublineages, i.e., “high‐titer”). 6 This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board and participants provided informed consent electronically. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact testing and Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test for continuous variables. All statistical analyses were performed on STATA 17/SE for Windows (College Station, TX).

HT and LT recipients were similar with respect to age (median, interquartile range (IQR) 62(46–69) years), time since transplant (5(3–11) years), vaccines received (96% received three mRNA vaccines, 4% received two mRNA followed by one Ad.26.COV2.S vaccine), time between the second and third vaccine (174 days (152–193, p = .59)), and antimetabolite use (68% vs. 79%, p = .086). However, more LT than HT recipients were female (62% vs. 47%, p = .028) and reported triple‐immunosuppression (68% vs. 13%, p < .001); fewer reported taking the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors (15% vs. 28%, p = .025).

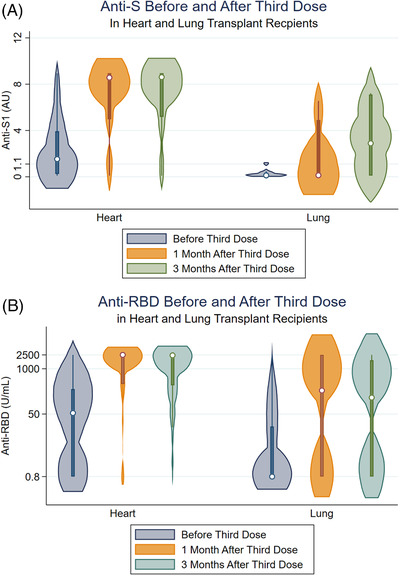

Before D3, 90/132(68%) HT and 39/91(43%) LT recipients were positive for anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies (p < .001). Of those tested 1‐month post‐D3, 100/111(90%) HT and 48/75(63%) LT recipients were seropositive. 86/111(77%) HT and 35/75(47%) LT recipients had anti‐RBD ≥ 250 or anti‐S1 ≥ 4, while only 65/111(59%) HT and 19/75(25%) LT recipients had anti‐RBD ≥ 2500 or anti‐S1 ≥ 8 U/ml (“high” titers). Of those tested 3 months post‐D3, 87/94(93%) HT and 45/68(66%) LT recipients were seropositive. 73/94(78%) HT and 26/68(38%) LT recipients had anti‐RBD ≥ 250 or anti‐S1 ≥ 4, while only 54/94(57%) HT and 16/68(24%) LT recipients had high titers 3 months post‐D3 (Figure 1). None sero‐reverted (positive to negative) over the 3 months of follow‐up post‐D3 nor reported incident COVID‐19.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Antibody response among heart and lung transplant recipients before and after receiving third vaccine against SARS‐CoV‐2. Median [IQR] anti‐RBD before D3 was 53.4 [.79, 258.6] U/ml (N = 92) for heart and .79 [.79, 22.1] U/ml (N = 80) for lung transplant recipients. One month after D3, median [IQR] anti‐RBD was 2500 [364.0, 2500] U/ml (N = 70) for heart and 237.5 [.79, 2500] U/ml (N = 68) for lung transplant recipients. Three months after D3, median [IQR] anti‐RBD was 2500 [339.2, 2500] U/ml (N = 67) for heart and 83.1 [.79, 2072] U/ml (N = 61) for lung transplant recipients. (B) Median [IQR] anti‐S before D3 was 1.53 [.26, 3.92] AU (N = 40) for heart and .12 [.1, .35] AU (N = 11) for lung transplant recipients. One month after D3, median [IQR] anti‐S was 8.57 [4.97, 8.94] AU (N = 33) for heart and .13 [.1, 4.9] AU (N = 7) for lung transplant recipients. Three months after D3, median [IQR] anti‐S was 8.76 [5.34, 8.94] AU (N = 27) for heart and 1.43 [.1, 7.22] AU (N = 7) for lung transplant recipients.

In this larger series of HT and LT recipients, we observed profoundly suboptimal antibody responses to third dose SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination, with poor seroconversion rates and lower titers than what has been reported for recipients of nonthoracic organ transplants. 5 Most notably, a third of LT recipients remained seronegative despite full vaccination, with significantly lower antibody levels among responders compared to HT recipients (over half of whom showed high‐level titers by 3 months post‐vaccination). These differences appear associated with more intense immunosuppression in LT recipients, given a much higher frequency of tripe immunosuppressive regimens and less use of mTOR inhibitors than among HT recipients. Attenuated humoral vaccine response thus represents one potential mechanism for reported poorer outcomes in thoracic recipients after vaccination, in addition to other differences in physiological substrate. Within the current landscape of highly transmissible SARS‐CoV‐2 variants demonstrating immune escape, immunoprotection after full vaccination among thoracic recipients, particularly LT recipients, is uncertain and additional interventions such as booster dosing or passive antibody immunoprophylaxis appear indicated. Antispike antibody testing after vaccination represents one component of personalized risk stratification efforts and counseling thoracic SOTRs.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: Jennifer L. Alejo, Jessica M. Ruck, Teresa P. Y. Chiang, Robin K. Avery, Aaron A. R. Tobian, Macey L. Levan, Daniel S. Warren, Allan B. Massie, William A. Werbel, Jacqueline M. Garonzik‐Wang, and Dorry L. Segev. Data analysis, acquisition, and interpretation: Jennifer L. Alejo, Jessica M. Ruck, Teresa P. Y. Chiang, Aura T. Abedon, Jake D. Kim, Robin K. Avery, Aaron A. R. Tobian, Macey L. Levan, Daniel S. Warren, Allan B. Massie, William A. Werbel, Jacqueline M. Garonzik‐Wang, and Dorry L. Segev. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: Jennifer L. Alejo, Jessica M. Ruck, Teresa P. Y. Chiang, Robin K. Avery, Aaron A.R. Tobian, Allan B. Massie, William A. Werbel, Jacqueline M. Garonzik‐Wang, and Dorry L. Segev. Critical manuscript revisions for important intellectual content: Jennifer L. Alejo, Jessica M. Ruck, Teresa P. Y. Chiang, Robin K. Avery, Aaron A. R. Tobian, Macey L. Levan, Daniel S. Warren, Allan B. Massie, William A. Werbel, Jacqueline M. Garonzik‐Wang, and Dorry L. Segev. Project supervision: Allan B. Massie, William A. Werbel, Jacqueline M. Garonzik‐Wang, and Dorry L. Segev. Funding: Jennifer L. Alejo, Jessica M. Ruck, William A. Werbel, Jacqueline M. Garonzik‐Wang, and Dorry L. Segev. Final approval of the version to be published: Jennifer L. Alejo, Jessica M. Ruck, Teresa P. Y. Chiang, Aura T. Abedon, Jake D. Kim, Robin K. Avery, Aaron A. R. Tobian, Macey L. Levan, Daniel S. Warren, Allan B. Massie, William A. Werbel, Jacqueline M. Garonzik‐Wang, and Dorry L. Segev. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: Jennifer L. Alejo, Jessica M. Ruck, Teresa P. Y. Chiang, Aura T. Abedon, Jake D. Kim, Robin K. Avery, Aaron A. R. Tobian, Macey L. Levan, Daniel S. Warren, Allan B. Massie, William A. Werbel, Jacqueline M. Garonzik‐Wang, and Dorry L. Segev.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

D. L. Segev has the following financial disclosures: consulting and speaking honoraria from Sanofi, Novartis, CLS Behring, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Veloxis, Mallinckrodt, and Thermo Fisher Scientific. R. K. Avery is an associate editor for Transplantation and has received study/grant support from Aicuris, Astellas, Chimerix, Merck, Oxford Immunotec, Qiagen, Regeneron, and Takeda/Shire. M. L. Levan has consulted with Takeda/Patients Like Me that are unrelated to the authorship of the study and is a Social Media Editor for Transplantation. Dr. Werbel receives speaking honoraria from AstraZeneca. The remaining authors of this manuscript have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to disclose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the participants of the Johns Hopkins COVID‐19 Transplant Vaccine Study, without whom this research could not be possible. They also thank the members of the study team: Brian J. Boyarsky MD, PhD; Alexa Jefferis, BS; Nicole Fortune Hernandez, BS; Letitia Thomas; Rivka Abedon; Chunyi Xia; Kim Hall; Mary Sears, BA; Alex Alex; Jonathan Susilo. They also thank Andrew H. Karaba, MD, PhD and Ms. Yolanda Eby for project support and guidance. This research was made possible with the generous support of the Ben‐Dov family and the Trokhan Patterson family. This work was supported by Grants T32DK007713 (Dr. Alejo), F32‐AG067642‐01A1 (Dr. Ruck), K01DK114388‐03 (Dr. Levan), K01DK101677 (Dr. Massie), and K23DK115908 (Dr. Garonzik‐Wang) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Grant K24AI144954 and U01AI138897‐S04 (Dr. Segev) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease; and Grants K23AI157893 (Dr. Werbel). The analyses described here are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

Jennifer L. Alejo and Jessica M. Ruck contributed equally to this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cochran W, Shah P, Barker L, et al. COVID‐19 clinical outcomes in solid organ transplant recipients during the omicron surge. Transplantation. 2022;106(7):e346‐e347. 10.1097/TP.0000000000004162 9900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Qin CX, Moore LW, Anjan S, et al. Risk of breakthrough SARS‐CoV‐2 infections in adult transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2021;105(11):e265‐e266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitchell J, Chiang TPY, Alejo JL, et al. Effect of Mycophenolate mofetil dosing on antibody response to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination in heart and lung transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2022;106(5):e269‐e270. 9000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boyarsky BJ, Werbel WA, Avery RK, et al. Antibody response to 2‐Dose SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccine series in solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA. 2021;325(21):2204‐2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dimeglio C, Herin F, Martin‐Blondel G, Miedougé M, Izopet J. Antibody titers and protection against a SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. J Infect. 2022;84(2):248‐288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karaba AH, Zhu X, Liang T, et al. A third dose of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine increases neutralizing antibodies against variants of concern in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(4):1253‐1260. 10.1111/ajt.16933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.